10

Research Applications

|

Key Messages Noted by Participants

|

The findings of research can have applications at the individual, family, environmental, and institutional levels to address the coexistence of obesity and food insecurity, said Mary Story, the moderator of the session on research applications. However the application of research can encounter obstacles at various levels of implementation. In the final session of

the workshop’s second day, three speakers looked at the ways in which researchers can help overcome these obstacles.

RESEARCH DIRECTED AT IMPROVING DIETS

Treating obesity clinically is usually very difficult regardless of a person’s income level, said Marlene Schwartz, deputy director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at Yale University. For food-insecure people, who already have many stressors in their lives, keeping food records and counting calories is for the most part “completely unrealistic.” A better option is to change the environment in such a way that people find it easier to eat healthful food.

Schwartz examined several research avenues designed to improve diets for everyone, including those who are food insecure or obese. American diets tend to be high in sugar, salt, and fats and low in fruits and vegetables, fiber, and calcium. To some extent, people are biologically predisposed to prefer high sugar, high salt, and high fats, Schwartz said. Even infants prefer these substances in their food, noted Schwartz.

Some foods also may have addictive qualities. Although this idea has been very controversial, evidence is starting to accumulate that certain foods can trigger addictive processes, Schwartz said. For example, foods that combine sugar, salt, and fat can override satiety signals. In addition, foods can have emotional connotations that encourage overeating.

A variety of policy options aim to decrease consumption of unhealthful food and promote healthful eating. Schwartz went through these options one by one while pointing to the potential of further research to improve diets, prevent obesity, and reduce the stigma associated with weight.

School Foods

A variety of options exist for changing what students eat in educational institutions, including limiting competitive foods in schools, limiting unhealthful foods in child care, and otherwise altering what students eat when they are in schools. For example, Schwartz and her colleagues have done research in Connecticut on taking unhealthful competitive foods out of schools and found that children’s consumption of these foods went down, with no evidence of their compensating by eating more of those foods outside of school (Schwartz et al., 2009).

Portion Sizes

Federal food assistance programs often talk about the minimum amount of food that recipients need, but they do not talk about a maximum. New

recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2010) and other organizations directed toward managing portion sizes could be implemented much more widely.

Marketing

As part of the Child Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative, the food industry has pledged to decrease marketing to children of unhealthful foods. Unfortunately, evaluations by the Rudd Center have determined that marketing of fast food, despite the pledges of industry, has increased. Instead of marketing the food, companies are marketing their brands. “They are marketing the experience of going to McDonald’s and having a Happy Meal or being with your family,” said Schwartz.

Zoning Restrictions

One option for communities is to use zoning laws or other neighborhood controls to control the foods available in those neighborhoods. More research needs to be done on both the potential and the limitations of such restrictions.

Satiety

Foods that are high in calories and low in nutrients tend not to be very satisfying. Research on how humans process food and how long they feel full after eating could clarify which foods achieve satiety while delivering sufficient nutrients.

Eating Disorders

Although anorexia nervosa is rare in the population, bulimia is more common. Schwartz believes that the relationship to the binge eating sometimes seen among food-insecure individuals should be further explored.

Food Reformulation

Some companies have been reformulating their products to be lower in sugar, salt, and fat, and labeling can encourage further movement in this direction. For example, when trans fats were included on nutrition labels, their use in many food products decreased, said Schwartz. Government and industry are currently working on new systems for labeling that “are going to make a big difference in terms of what food companies either do or don’t do in terms of reformulating their foods,” said Schwartz.

Food Costs

One policy option would be to make unhealthful food cost more. The action that has gotten the most attention is taxing sugar-sweetened beverages, but even this step has been politically controversial, and “the food industry is extraordinarily opposed to it.” If a substantial tax were instituted in one jurisdiction, its effects could be studied. Another option is to reduce the costs of healthful foods by subsidizing their purchase.

Nutrient Levels

Several food assistance programs have been promoting the consumption of more healthful foods such as fruits and vegetables. Another option is to reformulate healthful foods to make them more palatable, such as adding chocolate to milk or nutrients to cereals, Schwartz noted. “It is a whole lot easier to get people to eat more than to get them to eat less. It is psychologically easier. It is politically easier.” Unfortunately, the easy solution of turning to added sugar and flavorings to promote otherwise healthful foods that contain important nutrients (e.g., milk, yogurt, cereal) wins the battle but loses the war. We must stop teaching children that everything can taste like a treat, suggested Schwartz. Parents must resist the trap of only feeding children industry-labeled “kids foods.”

Changing Consumption

To change the quality of diets, two things must happen, Schwartz said. People must increase their consumption of healthful foods and decrease their consumption of unhealthful foods. These twin goals can generate competing messages. Personal choice and freedom need to be protected. “Once you start talking about restricting and taking things away, suddenly you are the food police.” Yet people also need to be protected from a toxic environment, which is how Schwartz said she would describe many of the food choices offered today.

Education must be a component of any such campaign, but Schwartz observed that it is difficult for education to compete with the environment and with the experience of being food insecure and hungry. When people are hungry, they are less likely to make a cost-benefit calculation about the nutrients in the foods they are considering. “That is why they tell you not to go shopping when you are hungry.”

Nutrition education also can send mixed messages. It can simply urge moderation and not make judgments about whether a given food is good or bad. A clearer message, said Schwartz, is that there are nutritious foods and other foods that should be seen as treats and eaten sparingly. People

need to learn about discretionary calories and how limited they are, which points to the need for research on the messages and information that are most motivating to different populations, including those served by the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Weight Stigma

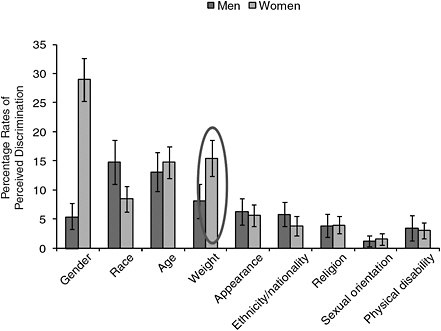

Schwartz raised the issue of weight stigma, which is an important part of the Rudd Center’s work. Despite the increase in obesity in the United States, weight remains a substantial source of perceived discrimination. Among adult women, weight is the second-greatest source of discrimination after gender, and it is the third-greatest source of discrimination among adult men (Figure 10-1). Furthermore, weight discrimination has increased over the past 15 years. “The idea that discrimination has gone down because the prevalence of obesity has gone up does not seem to be the case,” said Schwartz. “These data suggest that it is more common than discrimi-

FIGURE 10-1 Rates of perceived discrimination among Americans ages 35-74 years, data for 2004-2006.

NOTE: Error bars indicate 95 percent confidence intervals.

SOURCE: Puhl et al., 2008.

nation due to ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and disability, and for women it is actually more common than racial discrimination.” There are no federal laws that prohibit weight discrimination, and mass media messages reinforce weight bias. Also, the perception remains widespread that obesity results from a lack of personal control and willpower regardless of the environmental influences that foster obesity.

Nutritious Food Insecurity

Finally, Schwartz pointed out that the missions of the two communities that were combined at the workshop are slightly different. For example, the mission of a food bank is to alleviate hunger, while the mission of the Rudd Center is to improve diets. These different missions can lead to different measures of success. Food assistance programs may be more concerned with the amount of food distributed, money provided, or hunger alleviated, while obesity researchers may be more concerned with body weight, diet quality, and health improvements. In addition, these two concerns can have different relationships with the food industry. Perhaps a way to combine these concerns, said Schwartz, is through the idea of “nutritious” food insecurity, a concept that considers diet quality as part of the food insecurity equation.

FINDING THE SWEET SPOT IN GOVERNMENT FOOD PROGRAMS

There are substantial opportunities ahead to examine existing, and adopt new, public strategies and policies that have positive impact both on obesity and on food insecurity, and in some cases both, said James Weill, president of the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) in Washington, DC. We know some of these strategies already, and we need much more research to find others.

However, although there is an understandable focus on finding the “sweet spot”—the place where there are positive effects from a single intervention on both obesity and food insecurity, and there are some opportunities to do that—real life often offers only limited numbers of intervention points that address all priorities simultaneously and efficaciously. Weill said that we need also to pursue strategies that focus on primarily (maybe even exclusively) one goal—either food insecurity or obesity—while hopefully advancing and certainly not doing damage to the other sphere.

Positive Effects of Food Assistance Programs

As one example of a sweet spot, there is considerable evidence that SBPs are reducing hunger among low-income school children as well as reducing

obesity. There also is some evidence that children are vulnerable to gains in body mass index (BMI) and greater food insecurity in the summer when most of them are not consuming school meals. More research will help to determine whether there is a relationship between increased participation in summer food programs and reduced obesity.

Another sweet spot appears to be in child care. Meals and snacks that children receive through the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) provide needed nutrition and may reduce the risk of overweight among children from low-income families. “If we are going to seriously confront obesity in the country, we have to pay more attention to preschoolers and not just start paying attention when they are in school,” said Weill. “Early childhood is the critical time for growth and development in forming healthy patterns and habits.”

Federal after-school supper programs also have positive effects. Children have higher daily intake of fruits, vegetables, milk, and key nutrients such as calcium, vitamin A, and folate on days when they eat suppers in after-school programs. More needs to be learned about whether these healthful meals lead to reduced food insecurity and reduced obesity. The research opportunities are especially great in this area because only 13 states currently have these programs, Weill observed, so the programs’ effects can be measured across states. The passage of the child nutrition reauthorization bill would bring these programs to the remaining states, allowing comparisons between states and longitudinally.

Finally, food-insecure people over age 54 who participate in SNAP are less likely to be overweight than food-insecure nonparticipants. “These are a few [of the] places where the research to date suggests promising results and points to the need for further targeted research either to confirm the results or to tease out further the ultimate impact [of these programs] on food insecurity and obesity.”

Policy Changes to Food Assistance Programs

These examples of successful attributes of programs suggest changes to federal policies and research approaches that can yield future progress. First, if improvements in the nutritional quality of meals and snacks recommended by the Institute of Medicine and under consideration by both the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Congress are to reduce both food insecurity and obesity, those meals and snacks and the programs through which they are distributed need to be attractive to children and their parents. One key question is how to design and implement higher nutritional standards in school lunches and breakfasts to maximize participation. Simulation models developed by USDA of higher nutrition standards suggest that participation could decline modestly when such standards are

implemented. How can this decline be not only averted but also reversed so that participation grows?

States have had different experiences when implementing new school lunch standards in the past. One difference among states is that some address the issue of competitive foods in such a way that students have fewer alternatives to school breakfasts and lunches. Such differences should be studied, Weill said, along with the differential impacts of participation in school meal programs on obesity and food insecurity. There will be “great opportunities,” he asserted, to study the impact of different strategies as schools or districts across the country implement new standards in different ways and at different paces.

These opportunities—and the challenges posed by the issue of participation—are magnified in the case of school breakfasts. The implementation of new nutritional standards will require a considerably larger reimbursement boost for breakfast than for lunch (IOM, 2010). However, funding is projected to increase for lunches but not for breakfasts in the Child Nutrition Act, Weill said. This creates a risk that schools will drop SBPs or, more likely, will slow down recent efforts to boost participation as the new standards are implemented. This would be counterproductive.

One strategy for increasing participation in the SBP is offering breakfast free to all students in low-income schools, and ultimately offering breakfast in the classroom. This strategy is gaining increasing acceptance among schools and districts, which will provide increased opportunities to look at the effects of school breakfasts on food insecurity and weight.

Competitive Foods

With regard to the National School Lunch Program and SBP, the presence of unhealthful competitive foods is especially harmful to children from low-income and food-insecure families, Weill said. It not only potentially decreases the nutritional quality of their diets but also incurs costs that families cannot afford. The presence of competitive foods also creates peer pressure and stigma for the federal food programs that drive students who can least afford it to purchase competitive foods instead of eating free or reduced-priced meals at school. Better regulation of competitive foods could be linked with research to examine the effects of this regulation on food insecurity as well as obesity. Research on stigma and ways to reduce stigma also will be very valuable.

Child Care Programs

Federal child nutrition programs as a whole—and their consideration by Congress—focus much more energy and funding on school-aged chil-

dren than on preschool children. The Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is an exception, but participation in WIC drops off rapidly after 1 year of age; 2- through 4-year-olds are “underrepresented in the federal nutrition universe,” according to Weill.

The Child and Adult Care Food Program should be one central focus for Congress and USDA, he said. Congress is poised to mandate higher CACFP standards without any increase in reimbursement. For the child care program, such a step would raise the question of how to improve the nutritional value of meals and snacks while increasing the willingness of underfunded, community-based child care providers to offer the food program in family day care homes and centers. “If providers find that participating isn’t worth the cost … then there is a great danger that they are going to walk away from the program, and the children in child care will lose the opportunity to have healthful meals and snacks. We have to pay attention to how the change can be implemented in a way that works for struggling providers. It is an opportunity to stabilize, at least, and ideally to increase participation by child care providers. What are the variables that lead to success in maintaining or increasing provider participation?”

A complication is that changes in CACFP reimbursement made by Congress in 1996 as part of welfare reform have made it more difficult for family child care providers to participate in CACFP. Over the past 15 years the participation of children in centers in CACFP has risen significantly, but the participation by children in family child care homes in CACFP has dropped. At the same time, cash-strapped states grappling with federal mandates to get Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) applicants and recipients into job search and training programs and employment often have eased the resulting crunch by putting children in the cheapest child care available, which is family child care. The children in family child care could be disproportionately food insecure. “It is going to be essential going forward to make sure that the higher nutritional standards, which at least for now are unsupported by reimbursement increases, don’t adversely affect participation in the food program and thereby further increase food insecurity among some of the poorest and neediest [preschool children],” Weill remarked.

Food Insecurity and Obesity Among Adults

At the end of his presentation, Weill turned to the relationships among food insecurity, poverty, and obesity among adults. More needs to be learned about the relationship between SNAP, food security, and healthful eating, he said. A valuable research window has recently opened in which benefits are moderately higher because of the economic recovery act. Anecdotal reports from beneficiaries, stores, and social workers indicate that

benefits are lasting longer into the month and that those benefits are supporting the purchase of more healthful food. It is important to measure the potential impact that these better SNAP benefits may be having on both food insecurity and obesity.

It is possible that the nation will suffer through another decade without growth in incomes for the bottom portion of the population. In that circumstance, SNAP likely will remain the primary means to bolster the economic and food security of somewhere between 35 million and 50 million people, said Weill. “We need to know much more about what level of benefits can possibly impact obesity and food insecurity.” It also will be important to look at the impact of food cost and access to healthful food on low-income communities, particularly for those relying on SNAP benefits.

Finally, research on food insecurity and obesity among low-income people, and especially women with children, needs to look at the extremely high stress levels with which many live. Food insecurity and obesity both result from and cause stress and psychological suffering. “There are incredibly complicated interactions going on here that we have only begun to understand, and we need to understand them much more deeply,” Weill concluded.

POLICY-DRIVEN RESEARCH

California Food Policy Advocates is an organization that defines policy objectives and then identifies the kinds of research that will support those objectives, said the organization’s Executive Director Kenneth Hecht. It works on the assumption that federal food programs can prevent hunger and food insecurity, even if the link with obesity and food insecurity is not clear. Hecht provided three examples of this approach: (1) the provision of drinking water in schools, (2) obesity prevention in child care, and (3) increasing participation in school food programs.

Drinking Water in Schools

Free water to drink in cafeterias is limited in many California schools. When California Food Policy Advocates began to ask school administrators why this was so, they heard that federal food programs or contracts with soda distributors prohibited the distribution of water, but both of these explanations turned out to be myths. They therefore worked to have legislation introduced at the state level guaranteeing drinking water to students, but the governor initially vetoed the legislation. A few months later, a survey by the Department of Public Health of public schools in California found that 40 percent responding to the survey said they had no free drink-

ing water in their cafeterias. Given this information, the governor became the sponsor of a bill that he signed into law in 2010.

The bill states that schools in California shall provide free fresh drinking water in places where children eat. But in California, in contrast to many other parts of the country, students can eat in many different places on school campuses, which could make implementing the bill expensive. California Food Policy Advocates has therefore promoted research on how schools can meet this challenge. “It is not as simple as we thought it was.” The water should be tap water, since the drinking of tap water is a good strategy to prevent obesity and can be equitably implemented, said Hecht, but at least some schools in California do not have safe water. Fountains in hallways are “typically scuzzy or inoperative,” said Hecht. What if children do not want to enter a bathroom to get water? Will water replace the intake of important nutrients and calories, especially for younger children? Research will have to look at how schools deal with these and related issues if the law is going to work, said Hecht.

At the national level, the Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act may require that free fresh water be available for all of the child nutrition programs. “To be able to observe what happens in California could be very important in terms of a national rollout.”

Child Care

The second issue he discussed is child care. It is easier to focus on obesity prevention in schools that contain many children and are unified institutions. Yet child care is extremely fragmented, which makes obesity prevention initiatives difficult for preschool children.

One in four 5-year-olds entering kindergarten is already obese or overweight, and this condition is very difficult to reverse. At the same time, children at preschool ages are more amenable to changing behaviors, tastes, and preferences. “This seemed to us to be a wonderful place on which to focus obesity prevention policy and try to improve nutrition for kids before they go to school,” said Hecht.

However, there turned out to be very little information on obesity prevention measures in child care. As a result, California Food Policy Advocates worked with the Atkins Center for Weight and Health on a state mail-in survey and a smaller observational study in Los Angeles that came to very similar results. These results became the core of a bill brought to the state legislature that goes into effect in 2012. The bill promotes water, eliminates sugar-sweetened beverages, restricts milk to 1 percent or nonfat, and limits juice to being 100 percent fruit juice and one serving per day.

The success of the bill has been a great surprise to the organization because it calls for major dietary changes, but research still needs to be

done to guide those changes and prepare for future steps. Hecht noted several areas for future investigation: what does and does not go well in the implementation should be studied, the displacement of other beverages both in child care and out of child care should be monitored, and the compatibility of the measures instituted by the bill should be compared with other proposals for change.

School Meals

The third topic Hecht discussed is how to make school meals more attractive to students. These meals need to meet nutritional standards and be affordable for schools, but they also need to be meals that students want to eat, he said. Should students be involved in planning the meals? Should schools have closed campuses rather than open campuses for food, as has occurred with some California districts? Will students have enough time and places to eat if food choices are more limited? Should schools be used as laboratories for good nutrition? The schools being built today in California typically do not have places to cook, eat, or drink water.

California Food Policy Advocates has been working on an idea called scratch cooking, which Hecht described as “a movement toward real food.” How can schools be supported to have fresh food that is grown and prepared locally? Some school food service directors are doing “heroic work making this happen,” and USDA commodity foods are often very good. Yet more than half of the food from USDA is diverted to a processor before reaching a school district. “What we are trying to do is find very positive ways to make this thing work and, in the process, to give support to people who have an amazingly difficult job of trying to provide good food to kids.”

GROUP DISCUSSION

Moderator: Mary Story

During the group discussion period, points raised by participants included the following:

Sugar-Sweetened Beverages

All three speakers addressed a single question posed by Mary Story. The mayor of New York City has announced a plan to seek permission from USDA to prevent the city’s SNAP recipients from purchasing sugar-sweetened beverages with their benefits. Anti-hunger advocates feel that

this restricts freedom to purchase the foods that people should be able to buy. Obesity prevention advocates feel this is an opportunity to limit empty calories. Are such restrictions a good idea?

Schwartz said that she supports the idea. “I support any idea that is going to decrease sugar-sweetened beverage consumption.” People do not like the idea because it targets one population rather than applying to everyone, but such a policy emphasizes to the American public that these beverages are not a source of nutrition. Also, New York has asked to pursue the policy as an experiment that can be assessed after it has been implemented. “As a researcher, that sounds like a great idea to me.”

Weill said that he opposes the idea. His opposition is not based primarily on the impingement on the freedoms of SNAP recipients. Rather, an experiment should not be conducted initially on millions of people. If sugar-sweetened sodas were banned for everyone, or in public settings such as hospitals or colleges, said Weill, he could support that.

The problem with the proposal, said Weill, is that it is “picking on the poor in a symbolic fight over bigger issues.” It is premised on the view that society contains a permanent underclass rather than a population of people who move in and out of a program on a constant basis. Most stays in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program are short, and most people buy food with their own money as well as with food stamp benefits. Thus, a restriction would not necessarily affect what people buy. Also, restrictions on foods would make the people using food stamps very visible at the checkout counter, which could drive people out of the program. The substitution of EBT (electronic benefit transfer) cards for food stamp coupons has made one’s participation in the program much less visible, which has reduced the stigma associated with using the coupons and thus removed that barrier to people participating in the program.

Most important, said Weill, such restrictions are “one more way that the society will identify low-income people, poor people, as the other … and change their programs as a safety valve for a broader social problem and then not address the broader social problem.”

Hecht was clear in his support of the use of incentives rather than restrictions. He stated, “I don’t want to see people drinking sodas, and I don’t want to see low-income people targeted as the guinea pigs. There isn’t to my understanding any evidence to suggest that these folks make any different or worse decisions.” A better option would be to include incentives in SNAP to encourage people participating in the program to select fresh fruits and vegetables. Refinements to SNAP to make it the most effective program it can be will result in its getting the greatest possible support, “and it is going to need that support in the next few years.”

Older Adults and SNAP

A final comment in the discussion session involved older people, who participate in SNAP at much lower rates than younger people. This will become an increasingly important issue as the population ages and also because more grandparents are now raising children. Weill said that two-thirds of SNAP-eligible people get benefits, but among seniors the participation rate is only about 33 percent. He also said that this issue is a high priority for USDA, and AARP is conducting activities involving SNAP in many states.

REFERENCES

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2010. School meals: Building blocks for healthy children. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Puhl, R. M., T. Andreyeva, and K. D. Brownell. 2008. Perceptions of weight discrimination: Prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. International Journal of Obesity 32(6):992-1000.

Schwartz, M. B., S. A. Novak, and S. S. Fiore. 2009. The impact of removing snacks of low nutritional value from middle schools. Health Education and Behavior 36(6):999-1011.