Our destiny lies in understanding that humility leads to enlightenment and hubris leads to extinction.

Paul Falkowski, February 12, 2009

The publication of the report Biodiversity by the National Academy of Sciences/Smithsonian Institution in 1988 helped reframe the concept of biological diversity as a “global resource, to be indexed, used, and above all, preserved,”1 and captured the attention of the public and policy makers. Earlier concerns about biological extinction had led to the passage of the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973, but the 1986 National Academy of Sciences forum, on which the Biodiversity report was based, placed contemporary biological extinctions in a broader ecological, economic, and global development context. In subsequent decades, studies of biodiversity broadened still further to encompass diversity at the genetic and ecosystem levels. Concepts of ecosystem services and natural capital also emerged as a means of illuminating and capturing the value of biodiversity and ecosystems to human well-being. The imperative of an international approach to the conservation of biological resources resulted in the introduction of the Convention on Biological Diversity at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and its subsequent ratification by almost all of the countries of the world. It positioned the conservation and sustainable utilization of biological resources as two sides of the same coin, while also enshrining the principle of national sovereignty over biological resources and the requirement of fair and equitable

![]()

1 Wilson, E. O., ed. 1988. P. 3 in Biodiversity. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

sharing of the benefits from their conservation and sustainable use. Since then, a series of studies, assessments, and monographs from the National Research Council, the United Nations, and the academic community have sought to provide direction and impetus to further action on these issues. A sampling offered by James P. Collins included seven titles from the “bookshelf of reports in my office.”2 In 2005 the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment3—a massive effort involving more than 2,000 scientists from 77 countries conducted over the preceding 5 years and authorized under four international conventions4—attempted a comprehensive overview of the changing state of the ecological services that underpin human well-being.

By 2009 the biodiversity issue had developed new and far-reaching breadth and complexity. Scientific advances in microbial biology and molecular genetics had opened new possibilities for understanding fundamental aspects of the natural world that had previously been beyond our grasp. New instrumentation had made it increasingly possible to gather and analyze data over large geographic areas based on remote sensing from satellites, as well as land- and ocean-based sensors. Rapid advances in information management offered new opportunities for the synthesis and analysis of biological data. Yet, at the same time, the scientific community was increasingly aware of the limitations of current knowledge about many aspects of biodiversity, including the rapidity with which the different dimensions of biodiversity were being modified, eroded, or even disappearing entirely. Dr. Collins quoted estimates placing the number of species on Earth at 10–12 million, and stated that, at present rates of describing new species, just knowing what is out there will take 160 years. He also noted that by some estimates, 10–37 percent of remaining species could become extinct by 2050.5 As a result, many thousands of species will be lost before

![]()

2 In addition to the 1988 NAS/Smithsonian Biodiversity, his list included the following publications: NRC, 1992, Conserving Biodiversity: A Research Agenda for Development Agencies; UNEP, 1996, Global Biodiversity Assessment; NRC, 1999, Perspectives on Biodiversity: Valuing Its Role in an Everchanging World; F. S. Chapin, O. E. Sala, and E. Huber-Sannwald, eds., 2001, Global Biodiversity in a Changing Environment: Scenarios for the 21st Century; CBD Secretariat, 2006, Global Biodiversity Outlook 2; NRC, 2008, In Light of Evolution, Vol. II: Biodiversity and Extinction.

3 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

4 The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment was authorized under the Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, and the Convention on Migratory Species.

5 Thomas, C. D. et al. 2004. Nature 427, 145–148.

we learn of their existence, understand the role that they play in ecosystem functioning, and therefore comprehend what that loss might mean. The services that these species and ecosystems provide to human societies are, therefore, increasingly uncertain.

Global economic development and the implementation of new technologies have greatly improved many aspects of human well-being, but they have also extended the reach of human activity further into the natural world than ever before and have greatly increased its influence. Human mobility now connects ecological systems that have evolved in relative isolation over millions of years while technology facilitates the unsustainable exploitation of resources that accumulated over vast timescales. Human-induced environmental change is occurring across a very broad front and at unprecedented rates, with profound ramifications for atmospheric and oceanic chemistry, as well as species distributions and the process of evolution itself. These human interventions have global consequences, of which changing climates are only one manifestation. They also affect the landscapes and fisheries that underpin the global food supply, even as those resources will be required to support a human population at least 50 percent greater than exists today and three times as large as existed just 50 years ago.6 Measures proposed to feed and supply energy to the rising human population, while simultaneously mitigating climate-changing emissions (e.g., biofuels and intensive farming in the developing world), imply the large-scale modification of much of the world’s remaining habitat that supports wildlife. Ongoing alterations to global landscapes are amplified by increased ease of air and sea transport, which together with the widening and deepening of international travel and trade have succeeded in globalizing not only business and production but also diseases and natural pests on a scale never seen before.

The increasing capacity for humans to modify ecological systems and evolutionary and geological processes at a global scale poses challenges for understanding and managing ecosystems for human well-being, now and into the future. One hundred and fifty years after Darwin offered a framework for comprehending the origin of diversity in the natural world, and despite progress in understanding the processes by which ecosystems function and are sustained (see Figure 1-1), humankind is undertaking a

![]()

6 Lutz, W., W. Sanderson, and S. Scherbov. 2007 Update of Probabilistic World Population Projections. IIASA World Population Program Online Data Base of Results 2008, http://www.iiasa.ac.at/Research/POP/proj07/index.html?sb=5. Accessed July 2009.

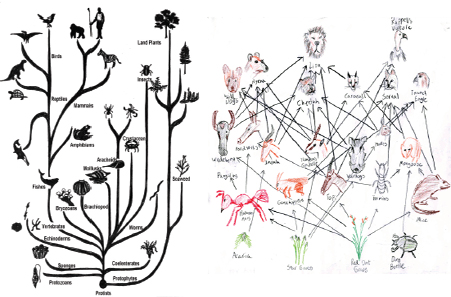

FIGURE 1-1 The tree of life and the web of life.

SOURCE: Michael Donoghue presentation. Tree of Life (left-hand figure) adapted from: Hotton III, Nicholas. A Simplified Family Tree of Life in The Evidence of Evolution. Smithsonian, 1968.

Darwin and Hutchinson were responsible for solidifying the two great metaphors that orient our understanding of biology—the notion of the tree of life and the notion of the web of life. Each, in his own way, managed quite comfortably, even seamlessly, to interdigitate the two. Today, my sense is that this, unfortunately, is a rather rare ability, and sadly the two have become quite separated from one another in the ways that we teach and carry out biological research. In my view, one of the greatest challenges before us, as scientists, is to work out the ways in which to connect the tree of life with the web life to truly reintegrate ecology and evolutionary biology.

Michael Donoghue, February 11, 2009

vast, uncontrolled global experiment in the reorganization of natural systems, the full consequences of which will be played out over millennia. The Symposium on Twenty-first Century Ecosystems was organized to highlight the ecological dimensions of critical challenges facing the world and our nation. The report highlights the complexity and interrelatedness of these issues, drawing on the overlapping themes that emerged from speakers’ presentations. It includes suggestions that could help mitigate the current and intensifying problems confronting the living world, while also offering improved approaches to environmental management based on developments in science, technology, and economics.

This report is not organized as a session-by-session summary of the presentations of the symposium. Instead, it focuses on eight key themes that emerged from the speakers’ presentations, all of which are linked by the imperative of a systems-based approach to both research and decision making about twenty-first century ecosystems.

THEME 1: LEARNING WHAT WE HAVE

Successful management of biodiversity is founded on knowledge of the variety of life, the processes by which it is sustained, and the ways in which it functions within ecosystems. Speakers in several sessions highlighted significant deficiencies in human knowledge of biological diversity and the processes through which species interact, but they also described new technologies, approaches, information systems, and analytical tools that have the potential to realize a step-change in the ways that information about species and how they are changing is acquired, maintained, and used. Some speakers emphasized the need to accelerate the acquisition of knowledge about the components of the natural world in the face of large-scale habitat modification and destruction and the accompanying eradication of species.

THEME 2: LEARNING HOW ECOSYSTEMS WORK AND ARE CHANGING

Ecosystems are now subject to a broad range of challenges that are unprecedented in their magnitude, rate, and diversity. Speakers described challenges that flow directly or indirectly from human activity related to land use, food production, economic development, and trade. They enumerated changes in ecosystems that are occurring at all scales, from global to highly local, with implications for ecosystem degradation, rapid

evolutionary changes, and the spread of microbes and other species that are ecologically disruptive and affect the health of animals, people, and plants. Many speakers noted that these problems appear to be exacerbated by climate change. Our understanding of the functioning of ecosystems has grown rapidly since the 1980s, but with that understanding has come increased insight into the complexity of such systems and the difficulty of fully comprehending the consequences of human-induced changes and the attendant functioning and effects on ecosystem health. The difficulty of accurately predicting the consequences of future changes is considerable, and several speakers emphasized the importance of a precautionary approach that can be adapted to respond to ongoing observations and analysis.

THEME 3: SAVING WHAT WE CAN

Saving biodiversity and sustaining ecosystem functioning will require an array of strategies, founded on the best possible understanding of what biodiversity exists, how organisms interact to create functioning ecosystems, and how these organisms and systems are changing. A variety of strategies were presented to address the ongoing erosion of biological diversity and ecosystem function, although numerous speakers emphasized that successful interventions require a systems approach and a broad understanding of the goods and services provided by species in ecosystems. Some speakers also asserted that successful conservation and management interventions inevitably depend on enhanced levels of public engagement, awareness, and support.

THEME 4: MANAGING ECOSYSTEM SERVICES AS COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS

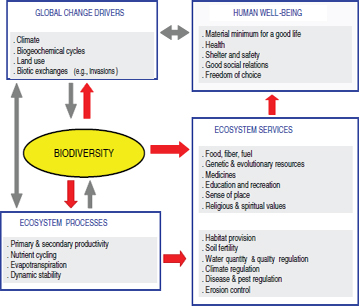

A recurring theme of the sessions was that decisions to conserve, manage, and use biodiversity and ecosystems for human benefit should be based on the best available information on the full suite of services that ecosystems provide, and awareness of the trade-offs among ecosystem services (see Figure 1-2). Some speakers observed that much research on and management of ecosystems has been approached in a fragmented way, in large part because of the difficulties of integrating different academic fields and administrative jurisdictions. A central theme of several presentations was the increased imperative for further integration both in science and in policy. Broader approaches, those speakers contended, are necessary to

FIGURE 1-2 The relationship of biodiversity to ecosystem services and global change. SOURCE: Sandra Díaz presentation, adapted from Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being. Biodiversity Synthesis. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

The conceptual model shows how global change drivers affect human well-being both directly and indirectly. Similarly, biodiversity in the broad sense affects the provision of ecosystem services both directly and through ecosystem processes. It may also alter the drivers of global change themselves.

Sandra Díaz, February 12, 2009

avoid unintended and often cascading consequences. Examples they cited included the effects of policies related to biofuels and carbon on agriculture, water resources, and biodiversity; of approaches to fisheries management on marine ecosystems; and of trade policies on the global dispersal of pests and pathogens. Understanding and managing such complex systems, several speakers noted, requires ongoing adaptive cooperation and collaboration among disciplines and across jurisdictions, both public and private, as knowledge continues to evolve.

THEME 5: INCREASING CAPACITY TO INFORM POLICY THROUGH INTEGRATED SCIENCE

Incorporating biodiversity and ecosystem science into policy decisions is not straightforward. Several symposium speakers described how the ecosystem services framework has helped demonstrate and quantify links between ecosystem functioning and the economy, as well as other aspects of human well-being. Economics and social science, they contended, must be integrated with scientific approaches to biodiversity and ecosystem management to support the development of effective public policy. Appropriate information must be made comprehensible and available to decision makers at all levels, both public and private. Some speakers emphasized that scientific input should be informed by awareness of both the strengths and limitations of research results and the complexities of policy making, and that effective policy advice should also take into account the need for public support of particular policy approaches.

THEME 6: INCREASING SOCIETAL CAPACITY TO MANAGE AND ADAPT TO ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

Environmental changes, from climate change to introduced pests and pathogens, can threaten both ecosystem functioning and the services that human beings derive from ecosystems. Some speakers detailed challenges to ecosystem services that are crucial to human well-being, such as food production, clean water, and regulation of atmospheric chemistry. They argued that both scientific progress and public education will be necessary to develop and implement well-formulated strategies for mitigation and adaptation. Climate shifts and other human-induced environmental changes that are already ongoing, and likely to intensify, some speakers contended, demand attention at every scale, from global to local, in all parts of the world.

THEME 7: STRENGTHENING INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS AND U.S. ENGAGEMENT AND LEADERSHIP

Numerous speakers pointed out that threats to biodiversity and ecosystem services that are global in scope require effective international coordination and cooperation if they are to be managed successfully. They characterized existing international cooperative efforts as insufficient to

meet the scale and scope of current and future challenges, and emphasized the opportunity—and urgency—for U.S. leadership in taking domestic action and bringing nations together. Two opportunities that several speakers mentioned specifically as vehicles for international cooperation were enhanced trade regulation and the nascent Intergovernmental Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).7

THEME 8: ACCOUNTING FOR THE VALUE OF NATURE

Some speakers contended that ecosystems and biodiversity will continue to suffer as long as economic incentives and associated social pressures fail to incorporate nonmarket externalities and to favor short-term exploitation and damage without regard to long-term sustainable management. Ecosystem services, they said, are frequently ignored because they are outside the market and so are unpriced, or because they involve services that are “public goods” that are open to all—this despite the fact that many ecosystem services, such as the provision of fresh water, are of fundamental importance, and degradation of such services has broad consequences. Proposals were made in some presentations to expand the system of national accounts to include changes in nonmarketed ecosystem services, and to record changes in the value of ecosystems (natural capital), to support public environmental decision making and encourage the design of policies that promote more sustainable economic growth that assures the long-term availability of vital ecosystem services.

Drawing on the eight themes that emerged from the speakers’ presentations at the symposium may help those scientists, nongovernmental organizations, and policy makers who are attempting to work more effectively together toward improving the future management of biodiversity and ecosystems, as well as the goods and services on which we all depend.

![]()

This page intentionally left blank.