E

Sustainable Fort Carson: An Integrated Approach

Christopher Juniper, Sustainability Planner, and Hal Alguire, Director of Public Works, Fort Carson, Colorado

BACKGROUND

Fort Carson is a U.S. Army garrison mountain post established in 1942 just outside Colorado Springs, Colorado. At that time, it was an economic development effort of the city: to buy a ranch and dedicate it to the U.S. Army. Today, Fort Carson is the second largest employer in the state of Colorado, generating about $1.3 billion per year in the local economy.

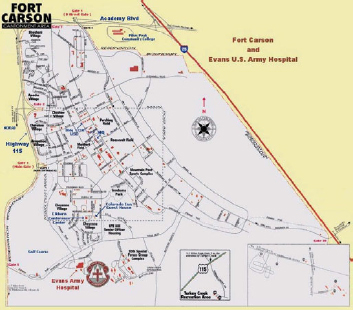

Fort Carson is adjacent to the southern edge of the Colorado Springs metro area, which has a population of approximately 625,000 people and borders the installation on two sides (Figure E.1). Fort Carson directly supports about 25,000 soldiers and has about 150,000 people, including retirees, that come to the installation for various services.

Fort Carson is about 2 miles wide and about 5 miles in length from north to south. The installation includes an airfield and six operating gates through which about 90,000 trips are made each day, and the traffic is projected to continue growing as soldiers return from deployment in the next 4 years and the area’s numerous military retirees, who access Fort Carson shopping and services, grow in number. In the past 5 years, Fort Carson’s building square footage has increased by about 50 percent, due mainly to the growth of Fort Carson’s soldier population. The garrison hosts about 10,000 soldiers—approximately 7,000 single soldiers in barracks and about 3,000 (eventually 3,500) married soldiers in on-post family housing.

The primary mission of the Mountain Post Garrison Team is to provide mission support and services including quality of life programs for Fort Carson soldiers, families, and community to enable forces to execute expeditionary operations and to minimize stress on soldiers and families in a time of persistent conflict.

Soldiers and families are under a great deal of stress. It is not uncommon at Fort Carson and other military installations to have soldiers who are on their fourth or fifth combat deployment. One of the best things that facilities managers can do to minimize stress is to create quality facilities for those soldiers and families. An added, long-term benefit is that it costs less to provide quality facilities because high-performance buildings save water and energy.

FIGURE E.1 Fort Carson and Colorado Springs. SOURCE: Courtesy of Fort Carson.

Sustainable development—high-performance buildings that minimize sustainability impacts—provides many tangible and intangible benefits. Because its execution sometimes means additional up-front costs and/or design time, it is critical that Fort Carson and other military installations on the sustainability journey have the continued support of military and U.S. government leadership; the quality of life for the soldiers and their families, and by extension the quality of our military, depend on it.

SUSTAINABILITY GOALS

In 2002, Fort Carson was one of the first three U.S. Army installations to pilot the concept of sustainability. At that time, Mary J. Barber and Tom Warren of the Fort Carson Directorate of Environmental Compliance and Management, invited people from around the community and state to help Fort Carson personnel set 25-year sustainability goals.

The charge was: What will Fort Carson actually do and look like if it were to be sustainable? Following education about what actually becoming sustainable means, seven visionary performance goals (Box E.1) and five process goals were developed for achievement by 2027.

To achieve these goals, the installation began with a leading-edge hybrid management system that combined the aspirational sustainability goals with the U.S. Army- and U.S. government-required Environmental Management System (EMS) designed to ensure environmental legal compliance. The 25-year goals were managed using 5-year objectives and 2-year work plans; continued involvement of community stakeholders was encouraged but not required.

At present, the sustainability goals have been integrated into the garrison’s strategic plans, which are updated by the garrison commander to reflect multiple objectives related to soldiers, families, and the workforce and Fort Carson’s training mission. The EMS has returned to its traditional focus on environmental compliance. Annual EMS audits are conducted through a U.S. Army self-auditing system.

In addition to the 25-year goals that the garrison commander committed to in 2002, he committed Fort Carson to annual reporting back to the Colorado Springs metro community on goal progress. As the goals were set at a conference-like event, the Fort Carson sustainability team produced annual community-inclusive sustainability conferences beginning in 2003 to provide updates on Fort Carson’s

BOX E.1

Fort Carson Sustainability Goals 2002-2027, as of 2010

- 100 percent renewable energy, maximum produced on the installation

- 75 percent reduction of potable water purchased 2002-2027

- Sustainable transportation achieved, characterized by 40 percent vehicle miles reduction from 2002 and development of sustainable transportation options

- Sustainable development (facilities planning)

- Zero waste (solid waste, hazardous air emissions, wastewater)

- 100 percent sustainable procurement

- Sustaining training lands—meaning ongoing capability of the biological health of training lands in support of the installation’s primary mission to train soldiers

progress and to provide the metro region with sustainability education and inspiration. Typical conferences hosted more than 500 participants. These Fort Carson community sustainability conferences became important annual events for the entire sustainability community of the region; conferences typically included more than two dozen supporting non-profit partners, ranging from environmental and peace groups to chambers of commerce and educational institutions.

To maximize the effectiveness for the region’s sustainability performance, which itself is a critical aspect of Fort Carson’s sustainability success, Fort Carson transitioned the conference to being hosted by a community non-profit and established an educational effort for all of southern Colorado, called Southern Colorado Sustainable Communities. Fort Carson organizes a “military track” as one of three to four primary subject matter tracks at the conference. Sustainable Fort Carson, the newly adopted name of the program, continues to produce an annual sustainability progress report for public distribution.

Another important ongoing feature of Fort Carson’s community stakeholder-based approach to sustainability performance is a monthly breakfast discussion of the achievements and challenges facing a specific sustainability goal, hosted by the garrison commander.

The sustainability education of the conference and the sustainability goal breakfasts are enhanced by a three-tiered approach to sustainability training for installation soldiers and civilian employees. Soldiers receive ongoing environmental compliance training and unit-embedded assistance from the Environmental Division of the Directorate of Public Works (DPW). The Environmental Division and the Sustainable Fort Carson programs collaborate to produce and deliver two levels of sustainability training: awareness training for all soldiers and employees and competence training for managers that includes integration of sustainability performance with the installation’s strategic plans.

A new garrison commander comes onboard every 3 years, and the DPW is now working with the fourth garrison commander since the goals were set.

The installation developed a logo for Sustainable Fort Carson in 2010 in order to better reach the nearly 30,000 soldiers and civilian employees and approximately 120,000 other installation users with consistent and modern messaging techniques (Figure E.2). It is hoped that the logo will help encourage more people to think, “I want to be part of this brand.” It reflects current Garrison Commander Robert F. McLaughlin’s understanding that sustainability is a “state of mind.”

FIGURE E.2 Fort Carson Sustainability Program logo. SOURCE: Courtesy of Fort Carson.

Renewable Energy

The local utilities and vehicle fuel providers are not ever planning to deliver 100 percent renewable energy to Fort Carson, despite the installation’s goal. Obtaining energy outside the existing system is unlikely to be cost-effective, although projects are continually investigated and evaluated. So the installation decided to collaborate with the Pikes Peak Sierra Club and local and statewide energy experts to create a regional sustainable energy plan, called the Pristine Energy Project. A Fort Carson sustainability planner with sufficient expertise, co-author of this appendix Christopher Juniper (contracted through Natural Capitalism Solutions), is co-leading the project with the president of the local Sierra Club and a small group of local energy experts. Technical support is being provided as needed on a volunteer basis by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), the Governor’s Energy Office, and two non-profits, the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project and the Colorado Renewable Energy Society.

The Pristine Energy Project’s focus is on identifying the barriers between the providers of sustainable energy and the customers who want it, including Fort Carson and other military installations in the region. For example, new wind-powered electricity is being considered by the local utility for sale to customers like Fort Carson, but the retail cost to the installation has been prohibitive. The Pristine Energy Project will create a plan by early 2011 that will identify for public policy makers a path toward helping the buyers who want renewable energy now and in the near future to be able to buy it from the providers at a reasonable cost. The plan will also outline a pathway to mainstreaming sustainable energy for the entire Colorado Springs metro region by 2030, supporting goals to achieve sustainability performance adopted in October 2010 (see Box E.1) by the regional sustainability planning effort that was also strongly supported by Fort Carson’s garrison commander and Sustainable Fort Carson planners.

Vince Guthrie, the utilities program manager in the DPW, is working on additional aspects of sustainable energy. Early in the installation’s sustainability journey, he purchased some inexpensive renewable energy credits (RECs) through the Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) in order to establish Fort Carson immediately on the sustainable energy path. The RECs offset approximately 28 percent of Fort Carson’s electricity from 2004 to 2009. The purchase was considered a “placeholder” while the installation worked on direct sources, such as wind, solar, and biomass. Through the work of the utilities program manager with the private sector and Colorado Springs Utilities, the city of Colorado Springs municipal utility that serves the installation with water and electricity, a 2-megawatt solar array was installed in 2008 (Figure E.3).

The array supplies a little more than 2 percent of the installation’s demand. Over its 20-year life it is projected to save $500,000, since the fixed costs of solar will gradually become lower than the currently projected increases in utility costs. Guthrie is also working with the Front Range Energy Consortium—

FIGURE E.3 Two-megawatt solar array installed at Fort Carson, Colorado, in 2008. SOURCE: Courtesy of the U.S. Army.

five Air Force and U.S. Army military installations that are investigating a 50-megawatt concentrated solar installation on a U.S. Army chemical depot site in Pueblo, 40 miles from Fort Carson. NREL is conducting a technical assessment of the proposed project in collaboration with the Army Environmental Command that is due in 2011, after which the partners will determine how best to move forward.

Two other efforts are under consideration: purchasing approximately 20 megawatts of wind power through the local utility if it becomes affordable, and the development of a wood biomass co-generation (electricity and heat) facility by the private sector on the installation, partly displacing the existing and aging natural-gas-powered boilers.

Concerning vehicle fuels, the Fort Carson civilian fleet fuel stations pump only E85 fuel, which is an alcohol-based, alternative fuel. And the installation, through the Pristine Energy Project, will complete a life-cycle sustainability performance assessment of all potential vehicle fuels and energy sources, including batteries, with a regional focus, in early 2011.

Sustainable Development (Facility Planning)

Fort Carson’s sustainable development goal holistically approaches three areas: land use/master planning, high-performance buildings, and storm water management (Figure E.4).

FIGURE E.4 (Left) Permeable Paver Project and (right) bioretention/stormwater management. SOURCE: Courtesy of the U.S. Army.

Fort Carson has completed 13 U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Silver and 14 LEED Gold certified buildings, which may be the most in the U.S. Army on any one installation (Figure E.5). That did not happen by accident. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha District Corps of Engineers, and its resident officers at Fort Carson are the garrison’s partners in design and construction.

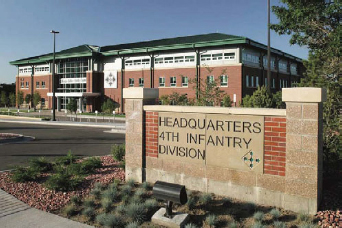

The U.S. Army requires its installations to develop buildings that could potentially be certified as meeting the LEED Silver ratings. However, Fort Carson’s DPW did not believe that the potential for certification would be as effective as formal certification by the USGBC. The first certified LEED Gold building in the U.S. Army was opened up to the 1st Brigade of the 4th Infantry Division more than a year ago (Figure E.6).

FIGURE E.5 Examples of LEED Gold and Silver buildings at Fort Carson, Colorado. SOURCE: Courtesy of the U.S. Army and Army Corps of Engineers.

FIGURE E.6 LEED Gold Headquarters of the 4th Infantry Division, Fort Carson, Colorado. SOURCE: Courtesy of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The design-build contractor of the facility, Mortenson Construction, initially targeted achievement of LEED Silver certification. Mortenson decided on its own to work toward additional points so that one of its projects could be certified as LEED Gold. It now can claim to have designed and built the first LEED Gold building for the U.S. Army. One of Fort Carson’s successful strategies is allowing private-sector design-build teams to “be all they can be” because they see high sustainability performance as a branding and marketing opportunity. And Fort Carson recognizes that the more sustainable the building’s design, the better it will serve the Army over the building’s lifetime.

One of the key parts to the installation’s sustainable development success is the passion exhibited by people in key positions both within the Corps of Engineers Omaha District and within the Fort Carson DPW. It is critically important to have motivated and LEED-trained people in the right positions, creating excitement and passion about high-performance sustainable buildings.

Sustainable Transportation

The transportation challenges of Fort Carson begin with its being a rapidly expanding, spread-out installation at the edge of a sprawling metro area with a poor mass transit system—resulting in 93 percent of the people arriving at Fort Carson in single-occupant vehicles, which creates major bottlenecks at installation access gates as well as on-post congestion. The long-term sustainable transportation goal is to achieve a 40 percent reduction in vehicle traffic through demand-reduction strategies and the development of cost-effective and sustainable alternative systems. The objective by 2012 is a 25 percent reduction in single-occupant vehicles, with achievement of a 40 percent reduction by 2017.

The transit model in the community is broken, although long-term plans are in development for a new governance structure (a likely recommendation is a regional transit authority with an independent and stronger funding mechanism). When Fort Carson’s sustainable transportation goals were established, public transit riders had to transfer just outside the installation’s gate to get anywhere, and they had to transfer again to access the installation, unless using the mobility services for disabled passengers. It was 70 minutes between buses on Fort Carson and 70 minutes between the buses serving the three routes at that transfer station, so an 8-mile trip from downtown could take 1.5 hours.

Only about 20 or 30 riders a day used the system—because they had no other choice. The installation estimates that at least 50 to 100 transit-dependent people need to access the installation every day for employment or medical and other services. By 2012, Fort Carson aims to partner with transit-providing organizations in the metro area to create direct-to-installation services for 500 people that will attract enough people who have other choices (“choice” riders) that non-choice riders receive sufficient cost-effective services; the system is being designed to expand over time to serve 2,000 daily riders. With 2009 increases in the federal mass-transit benefit to $230 per month maximum (about $5 per commute), the potential exists for direct-to-installation services that require little if any local tax subsidies. Focus groups and polls tell DPW that if it takes more than 10 minutes to arrive at destinations by transit, choice riders will not use it. Collaboration with local transit providers to achieve these “stretch” goals is ongoing.

At present, transit buses achieve about 3 or 4 miles per gallon, meaning that a bus must have 11 people onboard to match the energy efficiency of today’s cars (at the average occupancy of 1.6 passengers per vehicle). Buses will become even less comparatively fuel-efficient as cars such as the Nissan Leaf electric car, which is expected to achieve 99 miles per gallon equivalent, become available in 2011.

Ideally, the transit vehicles will be electric or electric-hybrids with maximum energy efficiency per passenger mile. Using electric power can reduce the $10 per hour fuel cost of traditional transit vehicles (of a typical $70 per hour total cost) down to about $1 per hour. The challenge is capitalizing the system with vehicles and supporting infrastructure, including the extra costs of electric vehicles.

Bus service to Fort Carson ended in 2010 because of city/regional tax revenue shortfalls. Federal government shuttle bus support is provided only for commuters or those engaged in Department of Defense business, or it can be provided by Fort Carson to its commuters only if all costs are covered by passenger fares. But as attainment of shopping, food, and medical services on the installation almost always requires motorized transportation, getting people to the gates without their cars only solves half the problem—with on-post carless mobility being the other half that is required to attract transit riders who could otherwise drive.

The installation’s sustainable transportation team is researching a mobility system that does not use private-occupant vehicles and instead uses private-sector-provided car sharing, low-powered-vehicle sharing (bikes, electric bikes, or other personal mobility devices), on-call transit services, enhanced telework strategies, and expansion of pedestrian and low-impact vehicle infrastructure. In 2010, bike paths were added to main streets in the central cantonment area by transforming two-way streets into one-way couplets, which makes room for bicycle lanes in place of left-turn lanes, without roadway expansion.

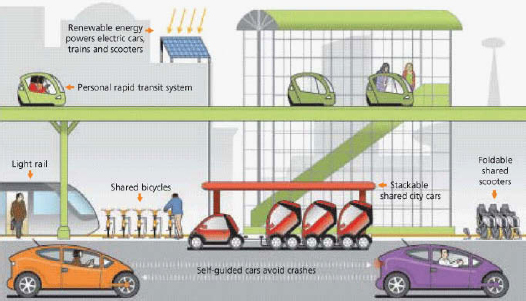

What are some game-changing sustainable technologies? Fort Carson has closely examined the potential for a personal rapid transit (PRT) system. The first-phase study, completed in 2009, designed a PRT system for the installation and estimated its capital and operating costs and potential revenues, overall sustainability performance costs/benefits, and potential for private-sector development and operation. The second phase, to be completed in 2011, will design commuter extensions into adjacent communities, evaluate system sustainability performance compared to other future transportation alternatives, and provide private-sector development opportunities.

PRT systems provide the convenience of autos by means of a system of computer-guided “podcars” that travel on a separate right-of-way using electricity. A passenger or group of passengers (up to six per car) call for a podcar from a system station, which then takes them directly to their destination station without stopping. Travel speeds exceed those of light-rail and buses because of the direct station-to-station service and the minimal wait for a podcar when one is called. High energy-efficiency is achieved (about 10 times that of today’s cars) because of the low weight of the podcars, their use of highly efficient electric motors, and the on-demand nature of the service such that vehicles are not moving unless demanded by a customer.

The preliminary Fort Carson-only system would cover 18 miles, deploy 36 stations, and cost $400 million to $500 million to construct. Over 40 years the cost per ride would be about $1.70, including all capital and maintenance costs—making it possible for a system that charges $2 per ride to earn a profit rather than require a subsidy. The system was designed for a podcar to be available to passengers within 30 seconds during non-peak hours and within a maximum of 8 minutes during peak hours.

A PRT system is now operating at Heathrow Airport in the United Kingdom (Figure E.7); the fundamental viability of the technology has been proven at a system operating in West Virginia for the past 30 years. Others are being planned in Sweden and in San Jose, California.

Another possibility is lithium-powered bicycles, which are now available for as little as $900, although typically they cost $2,000 or more (Figure E.8). The bikes will typically achieve speeds of about 20 miles per hour on their electric motors and will operate 20 to 30 miles on a single battery charge, depending on how much the rider pedals and other factors. With only half of a kilowatt-hour required to fully recharge them, lithium-powered bicycles get 2,000 to 3,000 miles per gallon equivalent. Bike sharing that uses electric bikes is better than traditional bikes on which riders may get hot and sweaty or overly cold in winter months. Private-sector companies are gearing up to provide electric-bike-sharing systems; Fort Carson is developing a request for proposals in FY 2011 for both bike-sharing and car-sharing on the installation.

Another sustainable transportation technology is the General Motors and Segway P.U.M.A. (Personal

FIGURE E.7 Personal Rapid Transit System operating at Heathrow Airport, United Kingdom. Photo courtesy of PRT Consulting. Inc.

FIGURE E.8 Electric bicycle.

FIGURE E.9 General Motors and Segway Personal Urban Mobility and Accessibility (P.U.M.A.) prototype. SOURCE: Courtesy of General Motors.

Urban Mobility and Accessibility) prototype vehicle (Figure E.9). The DPW is trying to determine if these low-impact vehicles, which operate on gyroscopes and are like a covered rickshaw that can transport two people, might be useful especially for carless mobility in the winter.

In short, Fort Carson is evaluating a wide range of technologies in order to identify and deploy the type of sustainable transportation system that would best serve installation users, would maximize life-cycle sustainability performance, and would be attractive to the private sector to build and operate. The system design will seek to maximize synergies between components, such as the multi-modal PRT station in Figure E.10 that is partially solar powered.

Sustainable Procurement

Fort Carson is pursuing adoption of an installation-wide sustainable procurement plan that will support compliance with Executive Order 13514 and the Department of Defense’s Strategic Sustainability Performance Plan of August 2010. Annual progress toward more sustainable procurement is described in detail in Fort Carson’s annual sustainability performance reports, available at the Sustainable Fort Carson Web site (www.carson.army.mil/paio/sustainability.html). The installation’s sustainable procurement strategy includes life-cycle sustainability performance assessments of batteries, lighting, mattresses,

FIGURE E.10 Multi-modal, solar-powered Fort Carson personal rapid transit (PRT) station concept developed by PRT Consulting. SOURCE: Courtesy of PRT Consulting.

cleaning systems, laundry systems, vehicle fuels and energy sources, and transportation system options, to be completed and publicly available in fiscal year (FY) 2011.

At present, all new major construction projects at Fort Carson are being LEED certified through the USGBC. Contracts require the design-builder to submit an implementation plan that includes the following:

- An air quality plan,

- A waste management plan,

- A commissioning plan,

- A LEED schedule,

- A personnel role list,

- A 500-mile radius map to show where materials are going to come from, and

- A narrative on how every point to meet LEED requirements will be achieved.

This approach has energized construction-design teams from the very beginning to look at how they are going to create a LEED Silver facility, at a minimum, on Fort Carson.

Fort Carson’s source selection boards look for contractors with past experience in LEED projects. Fort Carson’s DPW has four LEED-accredited professionals on staff as of FY 2011. The U.S. Army, and maybe other agencies that use the LEED criteria, should consider this type of training.