Approaches to Damage Assessment and Valuation of Ecosystem Services

Humans modify ecosystems in both intentional and unintentional ways, and impacts at the ecosystem scale, in turn, have both direct and indirect effects on human well-being. There is growing recognition that what is needed for informed environmental management and policy are measures that (a) link human actions to likely changes in ecosystems and (b) link changes in ecosystems to consequent changes in human well-being (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005; NRC, 2005a; TEEB, 2010). An analysis of environmental impacts can provide the link between human actions and environmental conditions. An analysis of ecosystem services—the benefits that people receive from ecosystems—can provide the link between ecosystem conditions and human well-being.

We begin this chapter with a brief outline of the important components of an ecosystem services approach, as well as issues related to assessing impacts and quantifying ecosystem services. A more detailed description of the ecosystem services approach and methods for valuation is presented in Chapter 4. Chapter 2 will review the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) process in the context of the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) spill. We discuss the NRDA process so that we can build upon it and offer suggestions for how it could incorporate an ecosystem services approach, which we believe to be a useful complement to the existing NRDA process.

AN APPROACH TO EVALUATING IMPACTS ON THE VALUE OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

Measuring the impact of the DWH oil spill on the value of ecosystem services requires assessing how the accident led to change in ecosystems, and how these changes led to changes in the provision and value of ecosystem services. Measuring such changes requires estimating the difference in the provision and value of ecosystem services with, versus without, the

oil spill. Much of the data for establishing baseline conditions—the status of the ecosystem had the spill not occurred—need to be collected as soon as possible after the start of the spill and before the effects are manifested. Without this effort, most regions would have insufficient observations to document the conditions of habitats and species at the time of the spill; an important consideration given that ecosystems are not static and change in response to other human activities. Often the closest that one can come to evaluating conditions post facto is to assemble evidence on conditions prior to the spill, or “baseline conditions.” Chapter 3 discusses baseline conditions in the Gulf of Mexico (GoM). As outlined in Chapter 1, an issue with using baseline conditions to assess what the present situation would be without the oil spill is that there are numerous other dynamic processes besides the oil spill that affect ecosystems and the services they provide, complicating the task of isolating the impact of the oil spill.

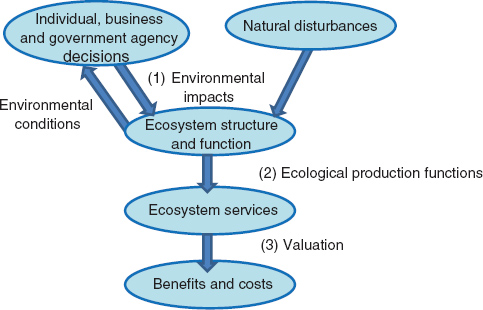

To measure the impact of human actions, either intentional actions brought about by a policy or management change, or unintentional actions, like an oil spill, requires understanding three important links (Figure 2.1). First, what are the impacts of human actions on environmental conditions that affect the structure or function of ecosystems? Ecosystem functions describe the internal processes of the ecosystem (e.g., energy fluxes, nutrient recycling, food-web interactions) while structure refers to the organization of the biophysical components that determine ecosystem functioning. Much of the current scientific work in the Gulf is an attempt to assess the chemical, physical, and biological impacts of the oil spill—an important first step in discerning the impact on ecosystem structure and function. Natural disturbances, such as a hurricane or changes in precipitation that affect discharge from the Mississippi River, also have impacts that lead to changes in environmental conditions. Again, as discussed in Chapter 1, natural variation can make it difficult to disentangle impacts of the oil spill from other factors influencing environmental conditions. This reality will be a fundamental challenge in all work related to the GoM oil spill.

Second, how do changes in the structure and function of ecosystems lead to changes in the provision of ecosystem services? “Ecological production functions” are used to describe the provision of ecosystem services as determined by the structure and function of ecosystems. They can be thought of as a “transfer function” or model that quantitatively describes the inter-relations of the ecosystem in such a way that changes in ecosystem condition (e.g., loss of habitat) translate to impact on ecosystem services (e.g., shrimp fishery yields). Ecological production functions can be used to predict how the provision of various ecosystem services changes with

FIGURE 2.1 The three important links from human actions to human well-being: environmental impacts, ecological production functions and valuation.

Adapted from NRC, 2005a.

changes in ecosystem structure and function. But, ecosystem function and structure and ecosystem services are not synonymous. Granek et al. (2009) give the following example to illustrate the difference between ecosystem structure and function and ecosystem service. “Mangroves, seagrass beds, and coastal marshes provide habitat for juvenile fishes (ecosystem function), which ultimately may contribute to commercial and recreational fish landings (ecosystem service), and wave attenuation (ecosystem function), which may provide protection (ecosystem service) for coastal property from storm surge. Alerting decision makers that habitat has been lost without connecting that loss to the decline of valuable fish harvests or coastal protection does not effectively communicate the importance or severity of that loss relative to the suite of issues managers are asked to address.” In the Granek et al. (2009) example, an ecological production function can be used to relate nursery habitat (structure/function) to a change in fishery productivity (service) or change in vegetation with wave attenuation (structure/function) to a change in coastal protection (service).

Third, how do changes in the provision of ecosystem services affect hu-

man well-being, and how can the value of the changes in services in terms of human well-being be quantified? An increase in the flow of ecosystem services generates benefits to people. A measure of the value of the benefit of ecosystem services to an individual can be obtained by observing what the individual is willing to give up in exchange for an increase in the flow of ecosystem services. Economists typically attempt to measure benefits in monetary terms by seeing how much an individual would be willing to pay to obtain more of an ecosystem service or, alternatively, what an individual would be willing to accept for a decline in an ecosystem service. Both market and non-market valuation methods can be used to estimate willingness to pay or willingness to accept. More detailed discussions of valuation applied to ecosystem services are presented in Chapter 4. Summing up the estimated values across all individuals affected by a change in services can generate an overall societal value that occurs because of the change in the ecosystem.

Much of the early work that attempted to quantify and value ecosystem services focused on estimates of the total value of ecosystem services rather than the policy-relevant (or in our case DWH-relevant) question of the change in value of services with change in management or environmental conditions. Costanza et al. (1997) used estimates of the value of ecosystem services by major ecosystem types to get an estimate of the value per hectare, which was then multiplied by the amount of area to get a total value of services by ecosystem type. Aggregating across these ecosystem types then generated an estimate of the annual value of the Earth’s ecosystem services of $33 trillion (with a standard error of plus or minus $18 trillion). This high-profile study was criticized by economists for misusing the results of studies of small-scale local changes in the context of large-scale changes (see, for example, Bockstael et al., 2000). Such exercises as in the Costanza et al. (1997) study may be potentially useful for highlighting the overall importance of ecosystem services but are not directly relevant to situations like the DWH oil spill. What is needed to evaluate an event like the DWH spill is to ask how the quantity or value of the ecosystem services in the GoM would differ with, versus without, the oil spill, i.e., what is the change in the value of services with the spill. The total value of ecosystem services is not relevant in this situation.

Given this brief introduction to the ecosystem services approach for assessing the impact of an event like the DWH on the ecosystems of the GoM, we now briefly review the NRDA process—the approach being used to evaluate damages associated with the DWH spill. In Chapter 4 we expand on our discussion of the ecosystem services approach and offer suggestions for how it could complement the NRDA process.

NATURAL RESOURCE DAMAGE ASSESSMENT

There are two overarching federal statutes that established the NRDA process: the Comprehensive Environmental Response and Compensation Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA) and the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA). Both of these statutes specify that the Executive Branch, through the President, has the responsibility for protecting and, where necessary, restoring the natural resources of the United States. The President is given the authority to delegate this responsibility and has done so through several federal departments. Those departments, in coordination with their state and tribal counterparts, are collectively termed as the natural resource trustees (33 U.S.C. Sec. 2607(b)(2); 33 U.S.C. Sec. 2607(b)(3), (4)). Trustees are responsible for acting on behalf of the President and the public to undertake NRDA and seek proper compensation and restoration for damages to natural resources.

The Exxon Valdez spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska, in 1989 led to the passage of the OPA in 1990 and to subsequent provisions for undertaking NRDA for oil spills. The Department of Commerce, through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is responsible for the NRDA process in response to oil spills in marine ecosystems. The OPA defines natural resources as land, fish, wildlife, biota, air, water, ground water, drinking water supplies, and other such resources belonging to, managed by, held in trust by, appertaining to, or otherwise controlled by the United States (including the resources of the exclusive economic zone), any state or local government or Indian tribe, or any foreign government (33 U.S.C. Sec. 2701(20) (see case study Box 2.1). Given that the committee is focused on the DWH spill, the discussion that follows will deal specifically with NRDA under OPA as implemented by NOAA.1

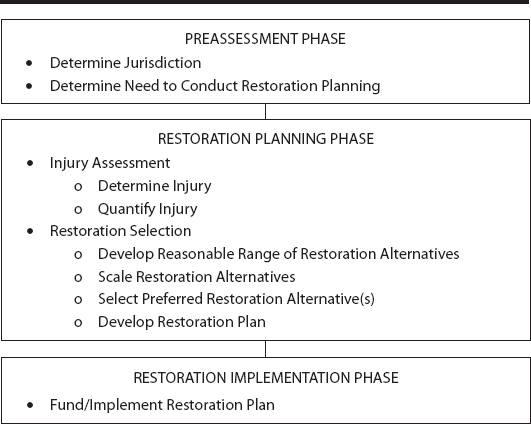

NOAA has a three-phase approach to NRDA:

1. preassessment,

2. restoration planning, and

3. restoration implementation.

The phases and methods are generally described in the applicable regulations (15 C.F.R. Sec. 990) and in NOAA’s Damage Assessment, Restoration, and Remediation Program guidance documents (Huguenin et al., 1996; Reinharz and Michel, 1996) (Figure 2.2).

During the preassessment phase, trustees seek to determine if there has

_____________

1 See http://www.darrp.noaa.gov/about/laws.xhtml#OilPollution.

BOX 2.1 NORTH CAPE OIL SPILL AND OPA: HIGHLIGHTING THE DAMAGE ASSESSMENT AND RESTORATION EFFORTS FOR IMPACTED LOBSTERS AND LOONS

The 1996 North Cape spill was the first opportunity for the U.S. government to apply the recently developed NRDA protocols under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA). The spill occurred during a severe winter storm in January 1996, when the barge North Cape released 828,000 gallons of home heating and diesel fuel in the Block Island Sound of Rhode Island causing the closure of a 650 km2 area of the Sound. The high winds (upward of 100 km h–1) and rough seas (5-7 m) mixed the oil throughout the water column and surf zone within 24 hours, exposing shellfish, lobsters, birds, and other organisms to oil.

Among the affected species, lobsters (Homarus americanus) were one of the most impacted, due in large part to the fact that a majority of the exposed individuals were vulnerable juveniles. The following exemplifies some of the efforts taken by the trustees—designated technical experts who act on behalf of the public and who are tasked with assessing the nature and extent of site-related contamination and impacts. These trustees are also tasked with deciding on the appropriate levels of restoration. In this example, the focus was on the commercially important lobster population.

Using diver surveys of lobster abundance (Cobb et al., 1999), the trustees estimated from sampling data that nearly 3 million lobsters killed by the spill washed up on the beach (Gibson et al., 1997). Three sampling stations were used and classified according to their proximity to the site of the spill: impact (nearest the site of the spill), control (clearly unaffected by oil), and transitional (between control and impact areas) based on reported records of beach strandings of lobsters and results of model simulations of the trajectory of the oil in the sediments. Because it was very unlikely that all lobsters killed by the spill washed up ashore, abundances were interpolated from both historical and sampled data and it was estimated that approximately 9 million lobsters were killed by the spill, of which 82 percent were juvenile (Gibson et al., 1997). Recovery time was anticipated to be four to five years for the lobster population to return to baseline levels which corresponds with the number of years it takes a juvenile lobster to reach legal harvest size.

Under OPA, the law required that impacted populations be restored to pre-spill levels. The final determination, using lobster mortality rates and other life history statistics, estimated that the 9 million lobsters lost could be replaced from approximately 18 billion eggs, which in turn would be the output of approximately 1 million adult female lobsters. The restoration efforts then led to a series of introductions of lobsters purchased by both the responsible parties and by the trustees. The lobsters were purchased from regional sources and marked with “V-notches” (clipping a notch out of the tails) to identify them as restocked lobsters that were to be released

by the lobstermen if harvested in local traps. Included in the restoration efforts were education programs for the lobstermen and seafood distributors, calculations of estimated non-compliance and the subsequent adjustments to the numbers of restocked lobsters, as well as monitoring and enforcement programs.

The goal of the program was to replace the lobsters that were killed in the North Cape spill. By protecting the restocked lobsters until the v-notches disappeared through successive molts, the delays in their harvest helped ensure that egg production led to increased numbers of juvenile and adult lobster populations. This restoration effort was part of a larger effort to “make the environment and public whole for the injuries to natural resources and services losses resulting from the spill.”a

Also impacted by the spill were loons (Gavia immer). For the loon population, the trustees used the observed mortality (67) to estimate a total mortality by employing a multiplier to account for dead loons not found. This approach led to the calculation of a total mortality of 402, indicating that five unobserved dead loons were counted for each observed mortality. As with the lobsters, recovery times (12 percent per year) were estimated using the life history, population information, and survival rates of the loons. The trustees also used a maximum life span of 24 years. Using these factors, it was concluded that with the death of 402 loons there was a loss of 3,641 loon-years.

As per the OPA, it was necessary to restore the loons that perished from the North Cape oil spill. But in this case, it was determined that restoring the summer breeding populations was best achieved via the protection of nearly 1.5 million acres of Maine forests and lakes that provide nesting habitat for at least 125 loon pairsb that were expected to overwinter in Rhode Island. The trustees along with local, state, and federal agencies, as well as non-governmental organizations and conservation groups, provided the funds to secure these lands.

This example of restoration as per OPA underscores the efforts taken to restore loons that were killed in the state of Rhode Island through the protection and subsequent breeding of loons in the state of Maine. While this potentially restored the loon population, the question remains whether the people of Rhode Island felt they were made whole. It also raises questions of compensation as a function of time.

_____________

a See http://globalrestorationnetwork.org/database/case-study/?id=283.

b See http://www.fws.gov/contaminants/restorationplans/NorthCape/NorthCapeFactSheetGeneral.pdf.

been a release of hazardous substances or oil, and the source. Once those are known, the second phase of restoration planning involves a number of sub-phases. In the case of the DWH, during the preassessment phase the source of the discharge of oil was clearly evident, and the trustees quickly recognized the potential for exposure of important natural resources to the oil soon after the incident began. Thus the preassessment phase soon evolved into the restoration planning phase. Ultimately the goal of restoration planning is to identify and quantify any injuries (impacts) to natural resources, and to estimate the amount of natural resources that have been lost. Trustees are given wide latitude in their use of assessment procedures (15 C.F.R. 990.27), including procedures to estimate natural resource losses

FIGURE 2.2 Overview of the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) process under the Oil Pollution Act (OPA) of 1990 (Huguenin et al., 1996).

and how to value those losses (15 C.F.R. 990.53). However, the regulations must be followed in order to obtain a rebuttable presumption (an assumption of fact accepted by the courts until disproved) if the process or results of the NRDA are challenged legally. Over the past 10-15 years, the practice of NRDA by NOAA and co-trustees for oil spills has evolved; the experience gained has been useful in improving the overall process (Barnthouse and Stahl, 2002; U.S. Department of Interior, 2007; Zafonte and Hampton, 2007). Even with the diversity of practical experience gained over the years, and with a fairly wide variety of historical events to draw upon, few if any of these historical events compare with the spatial and temporal scale of the DWH spill. As a consequence, the DWH spill presents a challenge for the ongoing NRDA efforts.

Injury Assessment

Under the OPA regulations, injury is defined as an observable or measurable adverse change in a natural resource or impairment of an ecosystem service. For example, oil from DWH that coats wetland plants or sea birds provides a small, yet highly visible example of injury to natural resources. As noted above, NOAA has developed and used well-recognized approaches for assessing injury or impact to natural resources, and many of these methods have been and continue to be employed for the DWH spill. In general, when assessing injuries (see 15 C.F.R. 990.27), trustees determine whether there is:

• an exposure pathway between the source and a natural resource,

• an adverse change in that natural resource as a result of exposure to the discharge, or

• an injury to a natural resource or impairment of a natural resource service as a result of response actions or a substantial threat of a discharge.

A simplified summary of approaches and the types of data collected under the NOAA guidelines (Huguenin et al., 1996) are shown in Table 2.1. As we note later in Chapter 4, numerous Technical Working Groups, composed of representatives from the natural resource trustees and others, are identifying data needs and designing and implementing studies to collect those data. These groups have been very active since the spill was first discovered, and some will continue their work and data collection for some time to come.

TABLE 2.1 Simplified Example of Commonly Collected Data for Injury and Impact Assessment That Would Be Relevant to the DWH Spill

|

|

||

|

Data Category |

Basis |

Approach |

|

|

||

|

Chemical |

Trustees need to establish source of the oil, nature and extent of spill, potential migration pathways of the oil, and potential exposure of key receptors (surface water, sediments, biota, and habitats). |

Sample and analyze media such as (1) surface water, (2) sediment, and (3) biota (wetland vegetation, marine mammals, reptiles, fish, etc.) in the vicinity of the spill and proximal to it where oil may be expected to migrate. |

|

Biological |

Trustees need to establish what biological resources have been exposed to the oil, and whether or not they have been harmed. |

1. Sample wetland vegetation to determine extent of oiling, |

This example focuses primarily on an estuarine wetland since these habitats tend to have good supporting physical, chemical, and biological data and are habitats well known to NRDA practitioners and non-practitioners. Less emphasis is placed on the open ocean even though it may be the largest area (receptor) exposed to the oil. Some organisms of specific interest to the trustees and the public (marine mammals for example) are included.

Modified from Huguenin et al. (1996).

We provide Table 2.1 to indicate how an ecosystem services approach could be incorporated into the NRDA process for the DWH spill. Table 2.1 is not representative of the full complexity of studies being undertaken for the DWH by the trustees, BP, and associated contractors. Rather, it is a simplified illustration of the kinds of data typically collected for NRDA and their basis in the regulations.

As we discuss later in the report (Chapter 4), there is a potential to reframe existing data or include additional types of data in Table 2.1 that would augment those data sets typically developed for NRDA purposes by NOAA, and in doing so, support an ecosystem services approach.

Restoration Selection

During the restoration planning phase, trustees have additional responsibilities once the injuries have been identified and quantified. Trustees estimate the natural resource losses based on the extent of the injuries. Under NRDA practice, losses are generally measured in ecological terms (e.g., number of acres damaged, number of sea birds oiled or found dead) rather

than in terms of losses in the value of ecosystem services (Dunford et al., 2004; Zafonte and Hampton, 2007). The losses determined by the NRDA process can then be used to assess the damages (the “debit”) to the relevant natural resources. In most cases, those damages (or the debit) translate directly (or can be scaled) into potential restoration projects that generate “credit” sufficient to offset the “debit.” For most NRDA cases, estimating or scaling the amount of restoration required generally follows equivalency approaches that are described in more detail later in this section. Restoration objectives can be the acres of habitat that need to be restored, the numbers of wildlife (birds for example) that need to be replaced, or other suitable projects allowed under the statute and regulations. These equivalency approaches also take into account the extent to which these habitats and resources would have recovered in the absence of human actions. Where damages do not translate easily into a particular restoration project, or where restoration projects in proximity to the injury are not readily feasible, funds may be provided as compensation and applied at a later date when a suitable restoration project is identified.

Current equivalency approaches may not necessarily capture the whole value provided by complex and/or long-term interactions within ecosystems. One scenario where problems may arise is in the case of chronic impacts of oil on an important natural resource that are not manifested or identified during the injury assessment, nor accounted for in the scaling of the restoration. In this situation the impacts may not be realized for several years and require additional human intervention and restoration to mitigate them (see also Coglianese, 2010). Given the spatial and temporal scales of the DWH spill, this issue will require additional attention during the development of restoration and monitoring plans, and exemplifies where the incorporation of ecosystem services analysis potentially will be of benefit. For example, the current assessment of injuries and service loss may lead to restoration in the near term. The assessment may also focus on restoration projects identified at that point in time. However, there may be future injuries and service losses identified through monitoring, and in that case suitable restoration projects may be more limited in number or type, in which case having an ecosystem services approach may again prove beneficial.

We also considered that in the current situation, and in reference to ecosystem services, that some potential impacts from the spill may not be known for some time, particularly where those impacts are detected far afield of the spill. Our focus has been on potential impacts within the GoM and adjoining states, and less on those that might be found in the future in the Caribbean or along the East Coast of the United States. In the event

that impacts are detected in the future in the Caribbean or along the East Coast, having a wider suite of potential restoration projects to draw upon will be of benefit.

Finding 2.1: The spatial and temporal scales of the DWH spill and the complexity of the GoM ecosystem make it unlikely that all important long-term impacts can be identified during the initial injury assessment.

After the injuries have been documented and quantified, the trustees, must “develop and implement a plan for the restoration, rehabilitation, replacement, or acquisition of the equivalent, of the natural resources under their trusteeship” (33 U.S.C. Sec. 2706(c)), using the relevant information developed for the case. To proceed with restoration planning, trustees also quantify the degree and spatial and temporal extent of injuries. Injuries are quantified by comparing the condition of the injured natural resources or services to baseline data, as necessary (Injury Assessment: Guidance Document for Natural Resource Damage Assessment Under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, the Damage Assessment and Restoration Program, NOAA, August 1996, at p. 1-4, sec. 1.4.2.1). The restoration plan typically is prepared at the end of the assessment process and is subject to public review and comment. These steps, injury assessment and restoration planning, are central to the goal of the OPA, 33 U.S.C. 2701 et seq., “to make the environment and public whole for injuries to natural resources and services resulting from an incident involving a discharge or substantial threat of a discharge of oil (incident). This goal is achieved through the return of the injured natural resources and services to baseline and compensation for interim losses of such natural resources and services from the date of the incident until recovery. The purpose of this part is to promote expeditious and cost-effective restoration of natural resources and services injured as a result of an incident. To fulfill this purpose, this part provides a natural resource damage assessment process for developing a plan for restoration of the injured natural resources and services and pursuing implementation or funding of the plan by responsible parties. This part also provides an administrative process for involving interested parties in the assessment, a range of assessment procedures for identifying and evaluating injuries to natural resources and services, and a means for selecting restoration actions from a reasonable range of alternatives” (emphasis supplied).

There are two key points to emphasize with the NRDA process, particularly regarding the use of equivalency approaches and restoration planning. First, pursuant to the OPA and implementing regulations, assessment and

restoration responsibilities are inseparable but tend to be managed in two distinct steps. Under the OPA, the measure of natural resource damages is the cost of restoring, rehabilitating, replacing, or acquiring the equivalent of the damaged natural resources; the diminution in value of those natural resources pending restoration; plus the reasonable cost of assessing those damages (33 U.S.C. Sec. 2706(d)(1)). Moreover, “Sums recovered under this Act by a Federal, State, Indian, or foreign trustee for natural resource damages under section 2702(b)(2)(A) of this title shall be retained by the trustee in a revolving trust account, without further appropriation, for use only to reimburse or pay costs incurred by the trustee under subsection (c) of this section with respect to the damaged natural resources. Any amounts in excess of those required for these reimbursements and costs shall be deposited in the Fund” (33 U.S.C. 2706(f)) (emphasis supplied). In other words, these funds are only to be used for restoring, rehabilitating, replacing, or acquiring the equivalent of the damaged resources.

We will refer to these actions collectively as “restoration options.” Thus, the trustee must assess damages from the responsible party or parties while attempting to keep in mind the potential feasible restoration options. Put differently, because restoration options represent the currency in which the responsible party or parties must pay for damages, the trustee should have a comprehensive understanding of the menu of restoration options throughout the damage assessment process. In the case where an oil spill results in injury to resources or services for which restoration options have not previously been developed, it is incumbent upon the trustees to explore and develop new suitable options. In addition, the trustees need to have a reasonable working knowledge of restoration projects that may be of interest to non-governmental organizations and the public, because they will have input to the final selection process. Further, the interests of the public will vary with the locale, habitats involved, and socio-economic settings of the area.

The separation of damage assessment from analysis of restoration options has been a challenge for NRDA practitioners for many years (Stahl et al., 2008). Despite using the term “restoration planning” to describe the second phase of the three-phase process, NOAA and other trustees tend to conduct the injury identification and quantification first. This is understandable as often the demands on the staff can be significant during the response period and data collection efforts. Sometimes it results in restoration option development being left for a later time. However, damage assessment is dependent upon restoration options. This reality has led to the development of a relatively new concept called “restoration up front (RUF)” (Stahl et al., 2008). The RUF concept was developed jointly among NRDA practitioners

in the public and private sectors, and evolved from collective experiences of those working both on CERLCA and OPA-type cases. The collective experience was that while time is spent responding to a spill, then assessing and quantifying the injuries, high-value restoration opportunities in the area of injury can be time-sensitive and thus “lost” if they are not addressed quickly. Since the RUF concept was developed, NOAA has developed policies that provide their NRDA practitioners with guidance on managing restoration opportunities early in the restoration planning process (NOAA, 2007b). One year after the spill, BP and the trustees reached an early restoration agreement in which BP agreed to provide up to $1 billion to allow early implementation of time-sensitive restoration projects, much the same as was described under the RUF concept. And, as noted earlier, public input to the selection process will be a key element in helping to decide which projects are funded and which ones are not.

The second key point, specifically related to ecosystem services, is that NOAA’s regulations require it to make “the environment and the public whole for injuries to natural resources and services” (15 C.F.R. 990.10). NOAA has historically relied on ecological-based equivalency approaches for assessing damages rather than approaches that restore the value of ecosystem services. These two approaches are as follows:

• Habitat Equivalency Analysis (HEA) measures damages in terms of the number of acres damaged. HEA fails to explicitly account for the fact that the value of a particular ecosystem service is dependent on the connection between that service and the public’s ability to use or to benefit from that service (Roach and Wade, 2006; Dunford et al., 2004); and

• Resource Equivalency Analysis (REA) focuses mainly on assessing injury to specific organisms rather than on the amount of habitat and is frequently applied to oil spills (Zafonte and Hampton, 2007). REA has some of the same drawbacks as noted for HEA, and is illustrated in the North Cape spill example (Box 2.1).

These approaches were designed to provide a tool that would allow both the responsible party and the natural resource trustees to estimate potential injury and scale restoration needs (Dunford et al., 2004). Each approach allows for inputs stemming from direct measurements in the field and laboratory, or through inputs derived from the published literature. Dunford et al. (2004) and Zafonte and Hampton (2007) detail a number of the strengths and weaknesses of these methods, including issues related to spatial and

temporal coverage and time factors (or service discounting). These methods have a rich history of use in cases over the years and are likely to be used in the DWH case. Thus in evaluating the potential for an ecosystem services approach to damage assessment, we seek methods that may complement and expand on HEA and REA.

In general, there is a tension between equivalency approaches such as HEA and REA, which are based on equivalency of habitat or organisms, and the ecosystem services approach based on equivalency of value of services. The committee plans to return to this issue in the final report. Further, this discussion should not be construed as an endorsement by the committee for a particular kind, size, or location of a restoration project, but as an illustration of difficulties involved with valuing specific restoration efforts in an ecosystem services context versus a resource equivalency context.

The challenge of equivalency or restoring the value of ecosystem services raises an additional issue of the distribution of benefits and costs across members of the public, i.e., restoration of value for whom? When an ecosystem is damaged near community A but restoration occurs near community B, the public in general might be made whole in the sense that the total value of ecosystem services is equivalent with restoration as before damage occurred, but community A remains worse off with the damage while community B is better off with the restoration. There will inevitably be some dislocation of benefits across time and space in any NRDA process. Dislocation of benefits across time raises issues of discounting. Discounting is the standard technique in economics for comparing future costs and benefits with present costs and benefits and is also used in NRDA (NOAA, 1999). The choice of a discount rate can reflect a value judgment about the “useful” life of an asset from which there will flow a stream of benefits. Choosing an appropriate discount rate for long-lived natural assets, such as those in the GoM ecosystems, can be challenging and will ultimately involve societal preferences at some level. Distributional questions, across both time and space, represent an important dimension that requires special attention, and will no doubt involve considerable discourse among the state and federal agencies and those affected communities. The North Cape spill (Box 2.1) provides a good example of the REA approach applied in this case to loss of lobsters and loons. The trustees were faced with restoring specific (or individual) resources and used REA rather than HEA. REA is more appropriate in those instances where individual or specific resources are harmed and restoration scaling for those specific resources is required. In other instances, particularly where a specific habitat (for example, wetland) has been injured, HEA may be more appropriate.

Finding 2.2: Although the equivalency approaches (HEA and REA) attempt to make the environment whole in the sense that habitats or populations of species are restored, this type of restoration does not necessarily make the public whole, as measured by the value of ecosystem services.

In Chapter 4 we discuss further the potential application of these equivalency approaches to the DWH restoration planning process, and some of the strengths and weaknesses associated with them. Here we provide a simple example to illustrate how attempts to value ecosystem services can address the shortcomings of equivalence approaches. Consider two acres of ecologically identical and equally impacted estuarine wetlands, Whiteacre and Blackacre. Whiteacre is located 100 miles further from a human population center than Blackacre. Assume under HEA the injury to Blackacre and Whiteacre are identical; however, the loss in value of ecosystem service could be substantially different. If Blackacre provides cheaper and easier public access for hunting and fishing, then oil-related impacts to Blackacre would result in a greater reduction in the value of ecosystem services than identical oil-related impacts to Whiteacre. The reason is that the ecosystem services approach takes into account the value of the resource to humans, whereas HEA and REA tend to place less (or no) emphasis on this aspect and focus more on the value of the habitat or the organism in an ecological sense. However, the calculus for accounting for ecosystem services at each site may differ, owing to the complexity in assessing those services for human benefit. The committee recognizes that NRDA typically emphasizes restoring resources near where they were damaged to reduce the difference in value caused by differences in location. Further, some NRDA practitioners emphasize the importance of restoration of ecological and human values (Knetsch, 2007; Abson and Mette, 2010).

To date, however, the majority of NRDAs do not appear to have utilized an ecosystem services approach, based on informal surveys of government and private sector practitioners conducted for the U.S. Department of the Interior (2007). The lack of application of ecosystem service valuation to NRDA does not appear to be due to a restricting provision in the statutes or in the regulations (see 15 C.F.R. 990.27; Gouguet et al., 2009; Munns et al., 2009). Recently, there appears to be more interest by federal agencies in using an ecosystem services approach in their decision processes (Slack, 2010; Compton, 2011).

Finding 2.3: Applied equivalency approaches focus more on the implicit value of the habitat or the organism in an ecological sense rather than the ultimate value of the resource to humans.

Finding 2.4: Habitat and resource equivalency approaches could be broadened to include an ecosystem services approach by consideration of the extent to which affected areas or resources generate benefits to the public.

One way in which this gap could be closed is through an expansion of the concept of the Service Acre Year (or SAY) that has been used in HEA. A SAY is the ecological service provided by one acre of habitat per year, where the flow of that service is to another ecological resource rather than to humans (Dunford et al., 2004; Stahl et al., 2008). The expansion of the definition of the SAY to include the value of services that flow from that habitat or ecological resource in terms of human benefits would readily incorporate ecosystem services into the ongoing NRDA process. In the example considered above, Blackacre would have higher SAY values per acre than Whiteacre to capture the fact that Blackacre provides greater public access and therefore generates greater value of ecosystem services. We caution that this hypothetical example does not include issues such as the public’s value for that wetland not related to access, the ability of wetlands to recover without human intervention, and other factors that could influence the comparison of the two wetlands. Nevertheless, expanding the concept of SAY to include the value of ecosystem services would allow practitioners to evaluate more fully the potential injury or impact to the GoM from the DWH spill, and provide a wider spectrum of restoration options than might result through the current approach. In addition, where it is difficult to restore resource values directly, thinking clearly about what public values have been damaged could help direct restoration efforts that make the public whole.

Finding 2.5: A more comprehensive assessment of the overall value of the resources could be obtained by expanding the definition of the Service Acre Year to include services that flow from a habitat or ecological resource to human benefits.

While the example of expanding the SAY is one potential avenue that trustees might pursue to incorporate an ecosystem services approach into the current NRDA process, we recognize it is not a panacea. For example,

incorporating an ecosystem services approach within the HEA method may be possible in the case of an injured habitat such as estuarine wetland but is likely to prove more challenging where the REA method is used to estimate loss and scale restoration for a specific organism. The majority of the area injured by the DWH spill is the open ocean, and the HEA approach may not be appropriate in this situation compared to REA. We provide more discussion on this point in Chapter 4.

Despite the challenges noted thus far, the valuation of ecosystem services could be included as a more central component of the NRDA process by interpreting ‘that which makes the public whole’ as the provision of ecosystem services of equivalent value. Consider, for example, the case of wetlands that we discussed in Table 2.1. These habitats are relatively well known and tend to have substantive supportive information whether physical, chemical, or biological in nature. These supportive data will be useful in the conduct of an ecosystem services analysis, a point we have touched on already and which we focus on again in Chapter 4.

If the public resources in question are viewed as only containing ecosystem functions provided by the wetlands, then the restoration, rehabilitation, replacement, or acquisition projects will focus on restoring ecosystem functions by improving or protecting wetlands. If, on the other hand, the public resources are construed as containing the ecosystem services provided by the wetlands (e.g., flood prevention, water filtration, and recreational opportunities), then the trustee could undertake a wide range of projects in an effort to make the public whole. From an ecosystem services perspective, restoring the categories of services noted above could be undertaken through a wide variety of projects that may diverge from a strictly ecologically based effort, such as physically replacing or restoring the injured wetland. Hypothetically, these could include such actions as constructing seawalls and storm-water treatment systems or enhancing or subsidizing hunting or fishing opportunities. In a strict ecosystem services evaluation, these projects could replace the services lost. However, this example is provided for illustrative purposes only, and the actual evaluation and selection of projects would be subject to discussion and review among the federal and state trustees, the public, and other interested stakeholders. In the latter context, preference is likely to be given to in-kind, in-place projects that provide services that reflect both ecological and human-based values. Making the public whole by restoring the value of ecosystem services versus making the environment whole by restoring equivalent habitat (HEA) or organisms (REA) could result in different restoration activities being undertaken. When possible, restoring damaged resources to their original condition will satisfy

both making the environment and the public whole. Of course, even when restoring damaged resources to their original condition is possible, trustees must face questions of how to account for damages from interim loss of resources between the time of injury and time of full restoration. For both interim lost resources due to damages and for cases where it is not possible to fully restore damaged resources, the equivalency question is unavoidable: trustees must answer the question of what restoration activities will provide a set of equivalent resources that make the environment and the public whole. As discussed above, simple application of HEA and REA that focuses on number of acres or numbers of organisms will not necessarily make the public whole because the value of ecosystem services might not be fully restored. On the other hand, restoring the value of ecosystem services might not necessarily result in making the environment whole. An ecosystem services approach that restores the value of ecosystem services via human-engineered substitutes (e.g., building a flood wall or a water filtration plant) may not result in making the environment whole. Restoration of services via human-engineered substitutes would probably not satisfy the requirement of making the environment whole even if the value of ecosystem services is restored. We return to the discussion of equivalency in Chapter 4.

Consideration of the value of ecosystem services rather than equivalency of habitat or population could help relieve what might be called the NRDA “restoration bottleneck.” While NRDA requires the trustees to assess and recover monetary damages from responsible parties, it also encourages the trustees to fully spend those funds on restoring, rehabilitating, replacing, or acquiring the equivalent of the damaged natural resources (33 U.S.C. 2706(f)). “Restoration bottleneck” refers to the fact that a NRDA trustee can collect money damages from a responsible party only to the extent that the trustee can conceive of feasible, productive restoration, rehabilitation, replacement, or acquisition projects. In practice, trustees, the public, and the responsible party often struggle to identify and develop a mutually acceptable project prior to the time of settlement, creating a “bottleneck.”

Finding 2.6: An ecosystem services approach has the potential to expand the array of possible projects for restoration through alternatives that restore an ecosystem service independently of identification of an equivalent habitat or resource, albeit with the caveat that these projects must in aggregate make the environment and the public whole. Evaluation of the impacts on ecosystem services as part of the damage assessment process would expand the range of mitigation options.

Under the OPA, the federal government is required to seek reparation for damages to natural resources due to oil spills. The NRDA process is the primary tool by which the government assesses the damage to natural resources, and within that process, has been the application of equivalency methods, HEA and REA. Unfortunately, this process relies on an assessment that does not necessarily address the reality that an ecosystem is a dynamic and interactive complex of species and their physical environment (Kornfield, 2011). Furthermore, the existing NRDA process may not adequately integrate the additional complexity of space and time into the assessment, which is a particular challenge when assessing the impacts of an event with the scope and duration of the DWH spill. The underlying question that the NRDA practitioners would like to address is “how did the quantity and value of ecosystem services change due to the DWH oil spill?” The ecosystem services approach can be useful in answering this question. An ecosystem services approach may provide a useful addition to the ongoing NRDA process as it avoids the “restoration bottleneck” by expanding the array of projects suitable for funding. This approach brings the “value” into human benefits rather than solely addressing habitat for habitat’s sake.

Finding 2.7: Habitat and resource equivalency approaches may not capture the whole value provided by large ecosystems such as the Gulf of Mexico because of the complex long-term interactions among ecosystem components.

A more detailed discussion of this approach and specific recommendations for its implementation with respect to a few key ecosystem services are found in Chapter 4.