Field Guide

New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast

January 19, 2011

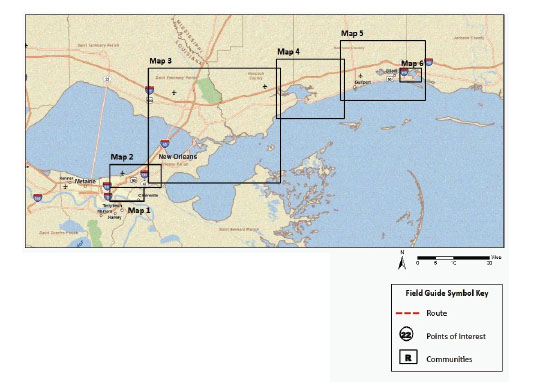

FIGURE: D-1 Overview of the field trip

Map created using ESRI ArcMap 9.3D Street Map Server

Maps by: Ronald Schumann III

Note:

Map 1: French Quarter to the Lower Ninth Ward

Map 2: Lakefront and New Orleans East

Map 3: Slidell and the North Shore

Map 4: Waveland to Long Beach

Map 5: Gulfport to Biloxi

Map 6: East Biloxi

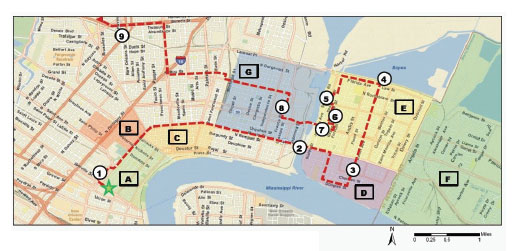

FIGURE D-2 French Quarter to the Lower Ninth Ward

Map created using ESRI ArcMap 9.3D Street Map Server

Maps by: Ronald Schumann III

Note:

1. Iberville Housing Development

One of the last surviving pre-HOPE IV public housing developments in New Orleans.

A. French Quarter: Original city limits of New Orleans founded on the natural levee, 1718.

B. Tremé: Historical area that has been home to African American servants and working class. A tightly knit community thrives here with little gentrification.

C. Marigny: Historically Creole neighborhood settled about 1800 where gentrification is ongoing. This neighborhood now attracts a wide range of individuals altering its culture.

2. Industrial Canal

Completed in 1923 as part of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, the canal connects Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River. Though greatly expanding New Orleans’ wharf space, the channel severed the Lower Ninth Ward from the rest of the city.

D. Holy Cross: The narrow natural levee thwarted development here until the 1870s. Slaughterhouses, rendering plants, and other nuisance land uses were confined to this farthest downriver corner of the city.

3. CSED – Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development [STOP] Doug Meffert, speaker

E. Lower Ninth Ward: Developed mostly between 1920 and 1970, this area sits on drained swampland. Originally the most ethnically diverse neighborhood in the city, it became the least diverse after the 1960s. Pre-Katrina residents were primarily poor and working-class African Americans with a high rate of homeownership.

4. Bayou Bienvenue Restoration [STOP]

Example of marsh restoration, a component of the neighborhood’s sustainability goals and the state’s coastal restoration plan.

5. Industrial Canal Floodwall Breaches

Two sections of floodwall (one-quarter mile in length) fronting the Lower Ninth Ward gave way during Katrina. An illegally moored barge may have been partially to blame. The neighborhood also suffered flooding from levee overtopping in neighboring St. Bernard Parish.

6. Make-It-Right Foundation

Funded by actor and philanthropist Brad Pitt, the foundation has enlisted architects nationwide in designing “green” homes to foster a return of residents to the Lower Ninth Ward.

7. Hurricane Katrina Memorial

The framed structure and empty chairs in the median of Claiborne Avenue stand as one of the few memorials to Katrina victims.

F. St. Bernard Parish: Community downriver of New Orleans developed mainly post-World War II. Most residents are working-class whites employed at local refineries or in commercial fishing. The area suffered both flooding and an oil spill from the Murphy Refinery during Hurricane Katrina.

G. Upper Ninth Ward: Like the Lower Ninth, this area is also built on drained swampland and sustained extensive flooding from another floodwall breach along the Industrial Canal.

8. Musicians’ Village

Spearheaded by New Orleans musicians Harry Connick, Jr., Branford Marsalis, and New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity, the village provides housing for displaced musicians and other disaster victims. While the village has heightened the recovery of the neighborhood, the current crisis caused by Chinese sheetrock in these homes has caused enormous stress on village residents.

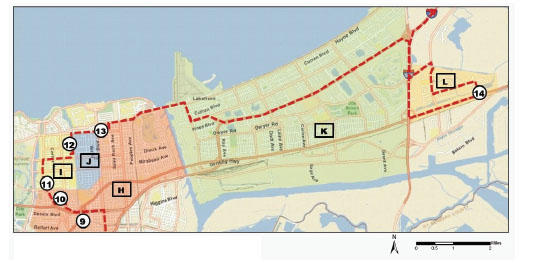

FIGURE D-3 Lakefront and New Orleans East

Map created using ESRI ArcMap 9.3D Street Map Server

Maps by: Ronald Schumann III

Note:

9. London Avenue Pumping Station

One of three pumping stations at the head of a northbound outfall canal. Used for street drainage.

10. St. Bernard Housing Development

New mixed-income community that replaces the former St. Bernard Housing Development.

H. Gentilly: Predominately African American suburban neighborhood. Gentilly Boulevard (U.S. 90) winds along the Gentilly Ridge, 2 to 3 feet above sea level. This natural berm saved houses to the south from flooding during Hurricane Betsy in 1965.

I. Paris Oaks and Filmore: Two neighborhoods. Paris Oaks (southernmost) is predominately middle-class African American. Filmore (northernmost) is upper-middle-class white and largely elderly.

11. Project Home Again

A nonprofit company that allows families without the resources to rebuild their own home to trade their damaged home or empty lot for a new home.

12. London Avenue Canal Breach

Canal wall undermined by sand boils.

J. St. Anthony: Working class, primarily black neighborhood.

K. New Orleans East: New Orleans’ suburban “city-within-a-city” developed during the oil boom of the 1970s and early 1980s. The area was developed to compete against suburbanizing Jefferson Parish to the west. The lowest elevation in New Orleans (12 feet below sea level) is located near Hayne Boulevard in New Orleans East.

L. Versailles/Village de L’Est: One of twelve communities planned for the eastern marshes of New Orleans in the 1970s and 1980s. It is home to a large Vietnamese community and has a large African American population.

13. “Urban Fishing Village”

Example of a community collectively agreeing to raise their homes.

14. Mary Queen of Vietnam Community Center [STOP]

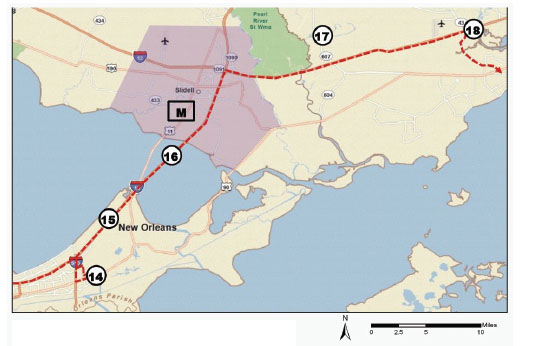

FIGURE D-4 Slidell and the North Shore

Map created using ESRI ArcMap 9.3D Street Map Server

Maps by: Ronald Schumann III

Note:

15. Lake Pontchartrain Hurricane Protection Levee

Levee raising is a part of 100-year flood protection for the metro area.

16. New Twin Span

Bridges for U.S.Hwy 11 and I-10 (left) and for U.S. Hwy 90 (far right) suffered damage from Katrina’s storm surge. Both I-10 and Hwy 90 bridges were rebuilt 20 feet higher than the old spans. The old I-10 Twin Span Bridge can be seen to the left at the hump.

M. Slidell: A bedroom community of New Orleans developed mostly since the 1960s. Only waterfront homes sustained heavy damage from surge, though the entire community suffered wind damage (left). Many pre-Katrina New Orleans residents (and even several corporations) have relocated to the North Shore.

18. Katrina High Watermark

Commemorative marker showing height of floodwaters at Exit 13 on I-10.

N. Waveland, Mississippi: Gulf Coast resort town turned working-class suburb. Most development occurred in the 1960s with the opening of Stennis Space Center. Residents displaced by Stennis’ construction also relocated here. Katrina’s highest storm surge measured 40 feet along the coast here.

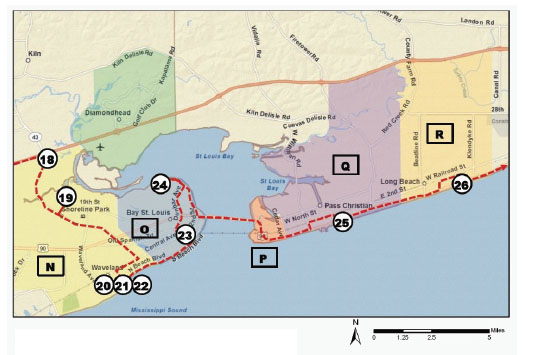

FIGURE D-5 Waveland to Long Beach

Map created using ESRI ArcMap 9.3D Street Map Server

Maps by: Ronald Schumann III

Note:

19. Waveland Back Bay

Recovery point. Storm surge from the back bay pummeled houses in this area. Note sea grass in the light pole from earlier photo and raised mobile home.

20. Waveland Community Civic Center [STOP]

David Garcia, Mayor

Mike Smith, Fire Chief

21. Katrina Cottages

Along with so-called FEMA trailers, these ubiquitous structures are used to house storm victims during rebuilding process.

22. Necaise Street

Recovery point, slow to return because of lack of water and sewer services.

O. Bay St. Louis, Mississippi: Historic resort town for residents of New Orleans and Mobile. The town also became a source of bricks and lumber for New Orleans in the 1800s.

23. Third Street

Recovery point near downtown Bay St. Louis.

24. Back Bay St. Louis

Elevated house on concrete pilings provides an extreme example of flood mitigation. Vegetation is reclaiming former subdivisions in this area.

P. Henderson Point, Mississippi: A small fishing community that has adopted among the toughest post-Katrina mitigation standards in Harrison County.

Q. Pass Christian, Mississippi: Shrimping town and historic resort village for New Orleans’ wealthy Creoles. Initiatives to land new industries have met with resistance from residents.

25. Scenic Drive Bluff

This 15- to 20-foot bluff saved many historic homes in Pass Christian during both Camille and Katrina, though the storm tide washed through the first floor of these residences.

R. Long Beach, Mississippi: Like Waveland, Long Beach is a working and middle-class suburban community developed since the 1960s.

26. Pass Christian and Long Beach, south of the tracks

The CSX railroad line running parallel to the coastline about one-half mile inland served as a barrier to the storm surge from Katrina. Structures south of this 6-foot berm received flooding, while those to the north received only wind damage.

S. Gulfport: Gulfport is the second largest city in Mississippi and one of the fastest growing cities in the state. In recent years the city has expanded north of I-10. Originally established as a lumber port in 1902; today bananas, agricultural products, and chemicals make up the bulk of the port’s tonnage. The Naval Construction Battalion “Seabee” Center in Gulfport is also a major area employer.

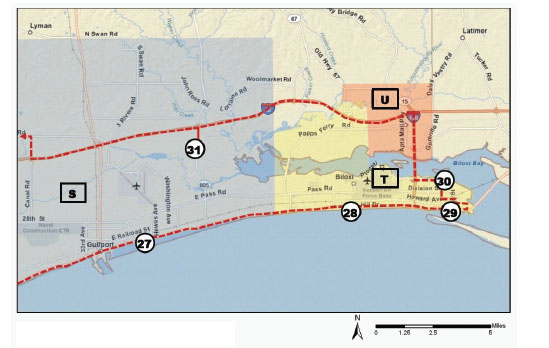

FIGURE D-6 Gulfport to Biloxi

Map created using ESRI ArcMap 9.3D Street Map Server

Maps by: Ronald Schumann III

Note:

27. Post-Katrina Slab Construction

Many homes rebuilt in eastern Gulfport along Beach Boulevard received approval before new base flood elevations were adopted. Many of these slab homes lack even wet flood-proofing.

28. Dune Reconstruction

Newly built fences, sea oats, and palm trees planted after Hurricane Katrina are aiding in dune accretion. Before the storm, the artificial beaches along the coast had lacked dunes.

29. Casino Row

Casino gaming became legal in 1990 for the Mississippi coast, provided casino structures were built over water. Post-Katrina laws allow gaming establishments to be located within 1,000 feet of the shoreline.

30. East Biloxi Vietnamese Enclave

Formerly, the most densely populated Asian enclave in the state. Asian residents made up 10–40 percent of the population, blacks 10–60 percent. Most were poor and working-class renters.

U. D’Iberville: Suburban community experiencing significant residential and commercial growth post-Katrina.

31. Knight Nonprofit Center [STOP]

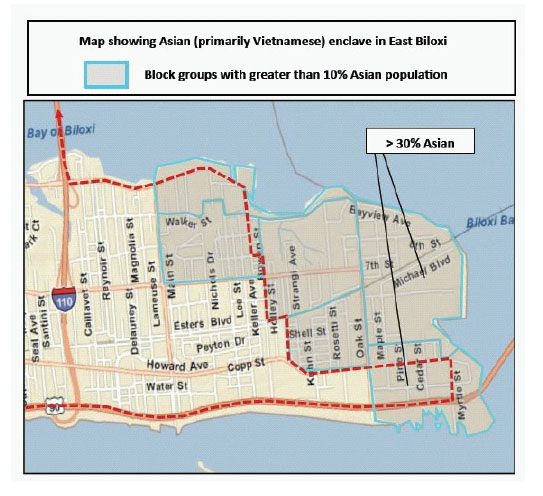

FIGURE: D-7 East Biloxi Detail

Map created using ESRI ArcMap 9.3D Street Map Server

Maps by: Ronald Schumann III

Note:

T. Biloxi: Historic capital of French Louisiana in the early 1700s, Biloxi’s economic base has transitioned from lumber and canning to seafood, tourism, and gaming. Keesler Air Force Base, built during World War II, also employs a significant number of area residents. Italians, Sicilians, African Americans from the Delta region, and more recently Vietnamese have made Biloxi home. Biloxi relies heavily on gaming taxes for revenue generation.

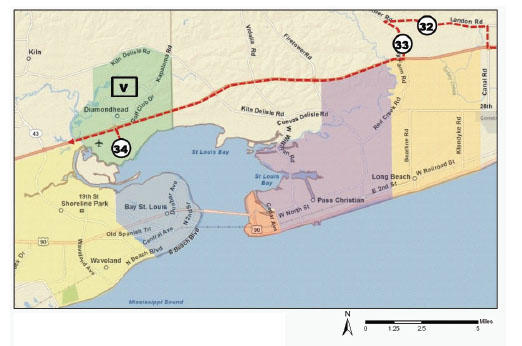

FIGURE D-8 Diamondhead and return to New Orleans

Map created using ESRI ArcMap 9.3D Street Map Server

Maps by: Ronald Schumann III

Note:

32. Katrina Cottage Graveyard

Holding area for Katrina cottages.

32. West Harrison High School

An example of a post-Katrina capital improvements project that seeks to locate critical infrastructure away from the Gulf. The high school also acts as a hurricane shelter.

V. Diamondhead, Mississippi: An upper-middle-class and affluent suburban community that emerged after the opening of Stennis Space Center. The community continues to expand even today.

34. Diamondhead Recovery Point

Recovery point, showing empty lots in place of former waterfront mansions. Another reminder of how Hurricane Katrina altered the lives of residents across the socioeconomic spectrum.

REFERENCES

Campanella, R. 2008. Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans. Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Campanella, Thomas J. 2006. Urban Resilience and the Recovery of New Orleans. Journal of the American Planning Association 72(2):141–146.

Ellis, D. 2004. Bay St. Louis, Waveland, and Diamondhead. In Landscapes of Coastal Mississippi. Biloxi, MS: Southeastern Division, Association of American Geographers.

Evans-Cowley, J. S. and M. Z. Gough. 2007. Is Hazard Mitigation Being Incorporated into Post-Katrina Plans in Mississippi? International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 25(3): 177–217.

Hassett, Wendy L. and Donna M. Handley. 2006. Hurricane Katrina: Mississippi’s Response. Public Works Manaement & Policy 10(4):295–305.

Kates, R. W., C. E. Colten, S. Laska, and S. P. Leatherman. 2006. Reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: A research perspective. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(40):14653–14660.

Kleiner, A. M., J. J. Green, and A. Nylander. 2007. A Community Study of Disaster Impacts and Redevelopment Issues Facing East Biloxi, Mississippi. In The Sociology of Katrina, edited by D. L. Brunsma, D. Overfelt, and J. S. Picou. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Li, W., C. A. Airriess, A. C. Chen, K. J. Leong, and V. Keith. 2010. Katrina and Migration: Evacuation and Return by African Americans and Vietnamese Americans in an Eastern New Orleans Suburb. The Professional Geographer 62(1):103–118.

Make It Right Foundation. 2009. Make It Right: Helping to Rebuild New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward. Make It Right Foundation 2009 [cited 13 Jan 2011]. Available from http://www.makeitrightnola.org.

Meyer-Arendt, Klaus J. 1992. Human-Environmental Relationships along the Mississippi Coast. Mississippi Journal for the Social Studies 3(1):1–9.

———. 1998. Casino Gaming on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. In Marine Resources and History of the Mississippi Gulf Coast, edited by D. M. McCaughan. Biloxi, MS: Mississippi Department of Marine Resources.

New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity. 2010. New Orleans Habitat Musicians’ Village. Habitat for Humanity 2010 [cited January 13, 2011]. Available from http://www.nolamusiciansvillage.org.

Project Home Again. 2010. Project Home Again: Helping New Orleanians Come Home. Project Home Again 2010 [cited January 13, 2011]. Available from http://www.projecthomeagain.net.

Souther, J. M. 2008. Suburban swamp: the rise and fall of planned new-town communities in New Orleans East. Planning Perspectives 23:197–219.