3

A Tour of New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast

On the first full day of the workshop in New Orleans, committee members took a bus and walking tour of New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Led by Ronald Schumann III, a graduate student in geography at the University of South Carolina who grew up in the New Orleans area and became a licensed New Orleans tour guide, the committee stopped in four locations in Louisiana and Mississippi to talk with residents, government officials, and directors of nonprofit organizations. Other local experts joined the committee on the bus for discrete portions of their tour, including, in New Orleans, Pam Jenkins, professor of criminal justice and women’s studies at the University of New Orleans; Doug Meffert, the Eugenie Schwartz Professor of River and Coastal Studies at Tulane University; Charles Allen III, director of the Office of Coastal and Environmental Affairs in New Orleans; and Tracy Nelson, director of the Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development. In Mississippi, the committee was joined by Tracie Sempier, coastal storms outreach coordinator for the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium.

This chapter describes what the committee saw and heard during its tour that illustrated some of the issues associated with resilience to hazards and disasters in New Orleans and along the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

THE NINTH WARD AND THE CENTER FOR SUSTAINABLE ENGAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT

Starting from the French Quarter, the committee traveled east through the neighborhoods of Tremé and Marigny to the Ninth Ward. In New Orleans, more disadvantaged groups tend to occupy neighborhoods at lower elevations, and

the Ninth Ward is one such neighborhood. Developed mostly between 1920 and 1970, the Ninth Ward, which is divided by the Industrial Canal into the Lower Ninth Ward and the Upper Ninth Ward, sits on drained swampland. Originally the most ethnically diverse neighborhood in the city, it became the least diverse after the 1960s. Pre-Katrina residents were primarily poor and working-class African Americans with a high rate of home ownership.

During Katrina, two sections of floodwall fronting the Lower Ninth Ward gave way, and a powerful surge of water, along with an illegally moored barge, flowed into the Lower Ninth. The neighborhood also suffered flooding from levee overtopping in neighboring St. Bernard Parish.

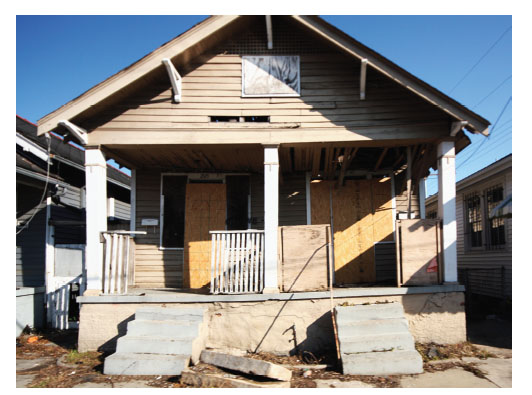

Many of the houses in the Lower Ninth Ward were destroyed in the flood (Figure 3-1). Today, many lots are empty or contain only a bare concrete slab. Many of the remaining houses are boarded up, some with a hole chopped in the roof where rescuers looked for survivors. The population has dropped from more than 17,000 before Katrina to 4,000 at most in the Lower Ninth Ward. People come into the ward to work on their property during the day, but they leave at night. Many former schools in the neighborhood also are closed, reflecting the reduction in student numbers and the conversion of many schools in New Orleans

FIGURE 3-1 Many homes in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans were destroyed by flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina. Picture by Neeraj P. Gorkhaly

to charter schools. However, two-thirds of the congregations in the Lower Ninth Ward have returned to the area, and faith-based organizations have played a major role in the neighborhood’s revival.

Several substantial recovery efforts are under way in the Ninth Ward. For example, the committee stopped at the Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development in the Holy Cross neighborhood, which is just south of the Lower Ninth Ward between the Industrial Canal and St. Bernard Parish. (The Holy Cross neighborhood is sometimes considered part of the Ninth Ward and sometimes treated as a separate neighborhood.) The Holy Cross neighborhood was built partly on the natural levee next to the Mississippi River, and its greater elevation gave it more resilience than the Lower Ninth Ward. The percentage of residents who have returned to the Holy Cross neighborhood is higher than in the Lower Ninth Ward—perhaps half of the 6,000 people who lived in Holy Cross before Katrina have returned.

At the Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development, the committee talked with Charles Allen III, a former director of the center and former president of the neighborhood association (who also spoke to the committee during its formal workshop the next day). As director of the center, Allen helped organize an ambitious effort that produced a recovery plan for the Lower Ninth Ward emphasizing sustainable development and green architecture. “We’re below sea level, so we were discounted,” Allen said. “People thought the neighborhood would go back to nature. As residents, we said, ‘Oh, no you don’t. We’ll recover this neighborhood.’”

In the Holy Cross and Lower Ninth Ward neighborhoods, homes are being rebuilt and elevated, said Allen. Many organizations and individuals have donated materials and time to the recovery effort. Key strategies have been to rely on energy-efficient materials, sustainable recovery efforts, and the entrepreneurial spirit of residents. Some older houses in the Ninth Ward were built with cypress, glazed brick, and tile, all of which can be dried out after a house is flooded, and similarly resilient building materials are being used in the recovery effort. The Holy Cross neighborhood has embraced carbon neutrality as a high ambition. The entire neighborhood cannot be redeveloped at once, Allen acknowledged, so planners have been looking at the use of some areas as urban farms while letting other areas go back to nature.

An important lesson of Katrina, Allen added, is that “the neighborhoods brought back New Orleans.” Neighborhoods need the support of government, but in some cases “it may be necessary for government to step out of the way.”

The current director of the center, Tracy Nelson, has a background in architecture, historical preservation, and sustainable development. She spoke to the committee about the use of funds allocated by Congress for historical buildings affected by hurricanes Katrina and Rita. She also pointed out that neighborhoods in New Orleans are culturally and architecturally distinct, and their cultural identities can be as important as their built environments. In rebuilding the Lower

Ninth Ward, she said, the cultural identity of the neighborhood should shape the built environment in a sustainable way.

In rebuilding neighborhoods, it also is necessary to take advantage of available resources. For example, research is under way to investigate the use of the Mississippi River for hydrokinetic energy through in-stream energy generation systems, said Doug Meffert, the Eugenie Schwartz Professor of River and Coastal Studies at Tulane University and deputy director for policy at the Tulane/Xavier Center for Bioenvironmental Research, who also spoke at the center. “We need to look at water as a strategic resource,” he said. The New Orleans area “is surrounded by water, but we are not benefitting from it as much as we should.” The committee also passed by a variety of homes constructed by the Make-It-Right Foundation (Figure 3-2). Supported by actor Brad Pitt, the foundation has enlisted architects nationwide in designing green homes to foster a return of residents to the Lower Ninth Ward. About 150 homes are being constructed most of them elevated above the ground. The houses generally cost more than $250,000 to build, but fundraising is being done to lower their selling price to around $150,000 for residents. Also, talks were under way with a developer

FIGURE 3-2 The Make-It-Right Foundation has been building homes in the Lower Ninth Ward to replace the more than 4,000 homes destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. Picture by Neeraj P. Gorkhaly

to bring a grocery store to the Ninth Ward, even though the ward did not have a grocery store before Katrina.

Before leaving the Lower Ninth Ward, the committee stopped to view the Bayou Bienvenue Restoration Project, which is a component of the neighborhood’s sustainability plan and the state’s coastal restoration plan. Large parts of New Orleans were built on coastal wetlands of cypress tupelo swamps. Bayou Bienvenue was one of the last such swamps left in the city, but it had been largely degraded because of saltwater allowed into the swamp through water engineering projects. Previously this bayou and its ecosystem had been cut off from neighborhoods because of high levee and flood walls; now a stair gives access to this rebounding wildlife area—a net improvement to quality of life and ecosystem and flood protection. The swamp is being restored in part through the release of treated wastewater, which is pushing off the saltwater and supplying nutrients for the swamp’s plants and animals. (This project also was discussed in the committee’s New Orleans workshop the day after the field trip.)

The committee also drove through the Upper Ninth Ward, which sustained extensive flooding from another floodwall breach along the Industrial Canal (Figure 3-3). The committee viewed the Musicians’ Village, an area of new home development spearheaded by several prominent New Orleans musicians including Harry Connick, Jr., and Wynton Marsalis, and the New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity. The colorful houses have furthered the recovery of the neighborhood. However, they were built using Chinese sheetrock that is highly susceptible to mold, which has forced many of the residents to move out of their homes while they are gutted and refurbished.

NEW ORLEANS EAST AND THE VIETNAMESE COMMUNITY

New Orleans East is a suburban “city within a city” developed during the oil boom of the 1970s and early 1980s. The area, which is bounded by Lake Pontchartrain to the north, the Industrial Canal to the west, the Intracoastal Waterway to the south, and swamp and marshland to the east, was built to compete against suburbanizing Jefferson Parish to the west of the city (see Appendix D for locations). The lowest elevation in New Orleans—12 feet below sea level—is located in New Orleans East. Many people who live in New Orleans East work in the seafood or oil industries, both of which were seriously affected by Hurricane Katrina and by the 2010 oil spill in the Gulf.

Most of the homes in New Orleans East were flooded by Katrina. Today, as in the Ninth Ward, the recovery has been very uneven from neighborhood to neighborhood and lot to lot. Some people had no choice but to come back and try to reclaim their homes. Others had the means to relocate elsewhere and have not returned to New Orleans. The current population of New Orleans East is about 56,000, compared with 96,000 before Katrina. The University of New Orleans, which is built on fill next to Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans

FIGURE 3-3 Flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina extended from the shore of Lake Pontchartrain (at bottom of photograph) through the Ninth Ward. Source: NOAA (http://www.katrina.noaa.gov/helicopter/helicopter.html; accessed May 30, 2011)

East, has about two-thirds of the approximately 17,000 students it had before the storm.

New building codes were not issued until well after the hurricane, so people who rebuilt quickly were subject to pre-Katrina codes. Some people have elevated their rebuilt homes above ground level, while others have rebuilt on grade. Many of the latter homes appear to be as vulnerable to flooding as they were before, and even the elevated homes may be vulnerable to wind damage. In general, the aftermath of the hurricane was marked by a conflict between getting people back into their homes and neighborhoods quickly and doing the long-term planning to create better housing and more resilient neighborhoods.

On the eastern edge of New Orleans East is the community of Village de L’Est, which is home to a large Vietnamese population. About 8,000 Vietnamese residents live among the heavily African American and Hispanic populations of New Orleans East. Before Katrina these groups did not have extensive interactions. But after the hurricane they were united by a number of causes, including a successful fight against a proposed landfill to accept debris from the storm. About

40,000 Vietnamese altogether live on the Gulf Coast, drawn to the area partly because of its climatic and geographic similarities to Vietnam.

The committee met with six members of the Vietnamese community in New Orleans East, with Tap Bui, the health outreach coordinator and community organizer for the Community Development Corporation, Inc., acting as translator. The six community members included Ms. Kim, Mr. Loc, Ms. Sy, Mr. Thien, Mr. Thieu, and Mr. Trung. These individuals described their community as hard working and cohesive and said that the Vietnamese community viewed the destruction caused by Katrina as an opportunity to rebuild the community to be even stronger. The most important assets of the community, said one participant at the meeting, were a spirit of hope and a spirit of community.

The Vietnamese community has a history of deprivation and hardship, especially among those who were not able to leave Vietnam in 1975 but came in later years. Many experienced tremendous losses in Vietnam and had to continually learn how to rebuild their lives. For example, most community members were not experienced in carpentry, but over the years they have been forced to learn. As one participant at the meeting said, “We are all carpenters now.” They said that they did not need much to survive—“just a roof and a light,” as one person put it. Reconstruction of homes and property was easier in the United States than in Vietnam, they said, because they had the support of local communities and governments. Also, the Vietnamese community in New Orleans East was larger and more cohesive than Vietnamese communities elsewhere in the United States, which was an advantage during the recovery period.

A large majority of the Vietnamese residents in New Orleans East are Catholic and attend the Mary Queen of Vietnam Church, with most of the rest of the community adhering to Buddhism. During Katrina the church was led by the Rev. Vien The Nguyen, who traveled by boat immediately after the hurricane to check on community members. The first mass was held in the church in October 2005 with just 20 or so families, but news that the church was open and operating spread among the community, and by December more than 2,000 people were attending masses.

Before the hurricane, the church had evacuation plans to help get residents out of town. About a third of the Vietnamese community consists of elders, so they needed special care to evacuate or to stay in place. Immediately after the hurricane, community members contacted everyone in the community to check on them. More than 90 percent of the Vietnamese community has returned to New Orleans East—a higher percentage than for the other ethnic groups in the area.

The captain of a fishing boat present at the meeting said that fishermen in the area got some help from government to rebuild their boats. However, government assistance came slowly, and the fishermen needed to get back to work, so they often spent their own money on repairs. They might borrow money from friends for repairs, and then lend out money when they were back in business. Later government assistance did defray some of their expenses, and some boats

were more severely damaged and required larger investments to repair. They were pleased and in many cases somewhat surprised to get funds from the government to complete repairs on their homes and boats. They also said that rebuilding would not have been possible without the support of the local, state, and federal governments, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The community members observed that they have received important government support in such areas as education and health care. Nonetheless, the community remains vulnerable to future shocks, and security remains a concern. The oil spill of 2010 had a serious impact on the community by first shutting down the seafood industry and then surrounding the industry with uncertainty. The future cohesiveness of the community is also an issue. The interpreter at the meeting said that she was one of the few young people in the community who remains fluent in Vietnamese. Many young people have left the community and have not returned. The community center used to teach Vietnamese, but it no longer does so, though Vietnamese is still taught through the Buddhist temple.

WAVELAND AND THE MISSISSIPPI COAST

Leaving New Orleans East, the committee took the new Highway 10 bridge across the eastern part of Lake Pontchartrain, which was rebuilt to be 20 feet higher than the span damaged during Katrina, to the town of Slidell, Louisiana, on the north shore of the lake. Many pre-Katrina New Orleans residents have relocated to the North Shore, along with several corporations. Slidell is a bedroom community of New Orleans developed mostly since the 1960s and is near the John C. Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Stennis is a research, development, and testing facility for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and the Mississippi coast’s largest single employer. Only waterfront homes in Slidell and adjoining areas suffered from storm surge, though the entire community experienced wind damage.

As in other parts of Louisiana and Mississippi, signs appeared in North Shore communities after Katrina warning of retribution if people were caught looting. In many areas affected by Katrina, law enforcement and military personnel were quite visible after the storm, which brought stability but also changed the atmosphere from one of cooperation to conflict.

Leaving Highway 10, the committee traveled to the Gulf Coast town of Waveland, Mississippi, a working-class suburban community of about 10,000 residents before Katrina that grew following the opening of the Stennis Space Center. Waveland is located southeast of Bay St. Louis largely on a coastal ridge with elevations averaging 10 to 15 feet above sea level (see Appendix D for locations). The storm surge during Katrina was as high as 25 to 30 feet in the city. The hurricane destroyed or damaged approximately 90 percent of residences and 100 percent of businesses.

A railroad embankment several blocks from the beach in Waveland carries the tracks of the CSX railroad. In previous hurricanes, the embankment has acted as a levee for portions of the town north of the tracks. In Katrina, however, storm surge came across the tracks and also entered Waveland from Bay St. Louis and other waterways (Figure 3-4), eventually making its way 12 miles inland from the shore (Appendix D). Of the 23 fatalities in Waveland, almost all occurred north of the railroad tracks, including a family of four whose home was covered by water.

The committee stopped at the Waveland Community Civic Center, which was rebuilt following Katrina to be more resilient to floods and wind. During Katrina, the water level was 11 feet inside the building, which was built on ground measuring 15 feet above sea level. The committee talked with David Garcia, the mayor of Waveland. Garcia was fire chief when Katrina hit and was among a group of rescuers in the fire station. When the station began to flood, they relocated farther from shore to the town’s wastewater plant, where they helped the employees of the plant evacuate. After that, said Garcia, “we became victims rather than responders” as they sought to ride out the storm in the plant.

FIGURE 3-4 Sea grass on light pole demonstrates height of the storm surge in a neighborhood adjacent to Bay St. Louis. Source: Hazard and Vulnerability Research Institute, University of South Carolina

Between the beach and the railroad tracks, the town was largely destroyed. “I was born and raised here, and I knew people who said that their homes were hurricane proof,” said Garcia. “Those homes are gone.” In fact, where homes did survive, it was usually because debris from demolished homes formed a barrier that protected intact homes from the waves. Almost a million and a half cubic yards of debris had been removed from the town as of March 2007.

The population of Waveland, at approximately 5,000 people today, is a little more than half of what it was before Katrina. One thing that has slowed recovery is that the town’s old trees had wrapped their roots around buried utility and sewer lines. When the trees were blown down in the storm, they ripped out the utilities, which have had to be largely replaced.

Another major impediment to recovery has been the expense of flood insurance. About 90 percent of the town is in a flood zone. Waveland participates in the Community Rating System in the state of Mississippi, which results in a premium reduction for residents who apply for insurance or renew their policy. But insurance remains very expensive, and rebuilding has been further slowed by the mortgage crisis. Partly to encourage rebuilding, the town has established a business incubator to revive economic activity.

Garcia said that the town “wasn’t prepared for a storm event of that magnitude.” Because the railroad embankment had protected homes north of the tracks in previous storms, fewer people evacuated from that part of town, which contributed to the higher fatality rate there. Garcia said that before Katrina it would have been impossible to get the entire town to evacuate, but after Katrina people knew that water can get north of the tracks. “When they see [emergency personnel] leaving, they know we are serious.”

A major problem in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane was knowing where people were and if they had evacuated or were buried in debris. Considerable effort went into tracking people down after the hurricane to determine whether they had survived.

Communications is an important part of emergency preparedness in Waveland today. As part of the Turn Around Don’t Drown Program, the town sends mailings to everyone in town to warn them of flood hazards. The information packets are geographically coded, so those in the highest risk areas receive additional information about their high risk. Discussion of rising sea level or climate change can generate strongly negative reactions among many residents, so emergency planners tend to talk in terms of higher and more frequent storm surges.

Garcia noted that the focus of media attention and relief efforts has been on New Orleans since Katrina. Some have referred to Waveland and other communities along the beach in Mississippi as “the forgotten coast,” even though the storm devastated those areas.

GULFPORT, BILOXI, AND THE KNIGHT NONPROFIT CENTER

After leaving Waveland, the committee made its way along the shoreline of Bay St. Louis, where vegetation is reclaiming subdivisions that were decimated by the storm. Some rebuilt homes have been elevated 40 or more feet above ground level, requiring a climb of several stories to enter the front door.

The committee then drove along the Gulf Coast through the towns of Henderson Point, Pass Christian, Long Beach, Gulfport, and Biloxi. Many structures were destroyed in the first few blocks from the beach, only some of which had been rebuilt (Figure 3-5). Along some parts of the coast, a 15- to 20-foot bluff saved many historic homes, though the storm surge washed through the first floor of most residences. Many homes rebuilt near the beach received approval before new base-flood elevations were adopted. Many of these slab on-grade homes lack even wet flood-proofing.

Gulfport is the second largest city in Mississippi and one of the fastest growing cities in the state. Originally established as a lumber port in 1902, the port today handles mostly bananas, agricultural products, and chemicals. Biloxi was the historical capital of French Louisiana in the early 1700s. Biloxi’s

FIGURE 3-5 Many homes in the blocks in the Gulf Coast were destroyed. Source: NOAA (http://www.katrina.noaa.gov/helicopter/helicopter.html)

economic base has transitioned from lumber and canning to seafood, tourism, and gaming.

Casino gaming became legal in 1990 for the Mississippi coast so long as casino structures were built over water. During Katrina, many of the casinos were heavily damaged, including several casinos on barges that broke up, floated inland, and were stranded several blocks from the beach (Figure 3-6). Post-Katrina laws allow gaming establishments to be located within 1,000 feet of the shoreline.

The committee’s final stop was at the Knight Nonprofit Center in Gulfport, near Highway 10 and approximately 5 miles from the beach. Many nonprofit organizations lost their offices during Katrina, and after the storm several nonprofit organizations and foundations formed a partnership to buy a building from Harrah’s Casino, renaming it the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation Nonprofit Center. Today more than 25 nonprofit organizations have administrative offices in the building.

The committee met with representatives of several nonprofit organizations (Box 3-1) who described the many benefits the center offers to nonprofits: The

FIGURE 3-6 Part of the Grand Casino Biloxi, which was floating off the beach of Biloxi, was deposited on the other side of the coastal highway by Hurricane Katrina. Source: NOAA (http://www.katrina.noaa.gov/helicopter/helicopter.html)

BOX 3-1

Representatives of Nonprofit Organizations Who Met with the Committee at the Knight Nonprofit Center

• Alice Graham, Executive Director, Mississippi Coast Interfaith Disaster Task Force

• John Kelly, Chief Administrative Officer for the City of Gulfport

• Rupert Lacy, Director, Harrison County Emergency Management Agency

• Tom Lansford, Academic Dean and Professor, Political Science, University of Southern Mississippi, Gulf Coast

• Reilly Morse, Senior Attorney, Mississippi Center for Justice

• Kimberly Nastasi, Chief Executive Officer, Mississippi Gulf Coast Chamber of Commerce

• Tracie Sempier, Coastal Storms Outreach Coordinator, Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium

• Lori West, Gulf Region Director, IRD, US Gulf Coast Community Resource Centers

building has abundant meeting space and parking for tenants and other users; tenants can share resources such as technology, office supplies, and phone lines and can share complementary expertise, as when one organization helps another write a grant; volunteers can work for more than one organization or can be referred from one nonprofit to another; and the rent at the building is much lower than it would be elsewhere, allowing organizations to do more with the resources available to them.

The building has abundant and comfortable space for meetings held not only by the tenants but also by outside users. Thus, the center can serve as a resource for other organizations. For example, the center has been used as the site of training to prepare individuals and organizations for future disasters.

The building is far enough away from the beach to be well protected in another hurricane. That knowledge provides organizations in the building with the confidence that they can respond immediately following a disaster rather than having to regroup in a disaster’s aftermath. Also, because groups are located next to each other, they are more likely to cooperate immediately after a disaster rather than working in isolation or competitively.

The nonprofit organization representatives also discussed how communities may define resilience differently because of their history, resources, or social structure. For example, a community may see some aspects of resilience as more important than others. These differences must be acknowledged but also can be accommodated through cross-sector collaboration. After Katrina, for example, six counties in southern Mississippi cooperated in forming a VOAD—Voluntary

Organizations Active in Disaster. This VOAD has put systems and protocols in place so that it can respond quickly to future disasters.

Many individuals, organizations, and communities on the Gulf Coast had no experience seeking disaster benefits from government, the representatives said. Furthermore, people were not exposed to risk in an evenly distributed way. Residential areas are heavily segregated in many Gulf Coast communities, so different racial and ethnic groups were affected to different degrees by the storm. Also, some African American populations express a resignation that they will not have access to resources. The nonprofit representatives emphasized the importance of helping people understand that they have the right to receive resources and ask questions. Some communities, such as the Vietnamese community, also need access to disaster coordinators and help with self-advocacy. Without assistance, they said, more experienced or sophisticated groups or individuals will receive more assistance while others receive little or no assistance. An important role for nonprofit organizations after Katrina was to try to make the distribution of disaster benefits more equitable and accessible.

The representatives from the nonprofit organizations also said that Gulf Coast had an advantage over New Orleans in that neighborhoods were not flooded for weeks after the storm. People could return to their homes and businesses and begin to rebuild. Congress also appropriated unprecedented amounts of money for disaster relief and gave the states discretion in how to spend the funds. This funding led to major infrastructure improvements such as bridges and public facilities. However, many people needed help from nonprofits to apply for housing assistance. In this respect, one measure of resilience is the ability of communities to bring forces to bear to correct courses established by state or federal agencies.

A powerful impulse after a disaster is to rebuild, even in areas that are highly dangerous, the nonprofit representatives said. When government prohibits building in an area or offers buy-outs of private property, people can object, especially in regions that favor private property rights and small government. Yet government and the insurance market ultimately will determine whether people are able to build in a given place or not. Over time, private property can be taken off the market and gradually be converted to other uses.

One important issue for nonprofits, the representatives noted, is the provision of alternative housing after shelters have been closed but before people can return to their homes. For example, during Katrina, people were sheltered in schools, but they could not remain in schools for the long term. The creation of stand-alone shelters is expensive and subject to complicated and sometimes counterproductive governmental restrictions. For example, long-term shelters need showers, and government regulations influence which kinds of structures can have showers. Government-provided housing was not available to all people after Katrina, and such housing cannot be guaranteed after future disasters.

Another point the representatives from the nonprofit organizations raised is that a key aspect of resilience is the existence of networks that allow different parts

of a community, whether economic, social, political, or cultural, to interact with each other. Informal networks existed before Katrina, such as networks of law enforcement agencies. After Katrina, boundaries between institutions and jurisdictions disappeared for a period, producing an extraordinary level of collaboration. These networks need to be formalized through mechanisms such as VOADs to continue communications and collaboration. Catastrophes such as Katrina can obviate previous disaster planning because of the magnitude of their impacts, requiring as much collaboration as possible. Disaster relief also begins locally and ends locally, since people in the community look to local organizations for guidance, not to the state or federal government.

The post-Katrina period has seen the emergence of resilience entrepreneurs who can help establish networks and regularize emergency processes, the nonprofit organization representatives noted. These individuals can help drive cross-sector collaboration outside government. Citizen advisory groups and other mechanisms also exist for bringing people together.

The private sector plays a crucial role following a disaster in helping to get people back to work and making money. Small businesses may experience special difficulties in resuming operations, requiring that government and nonprofit organizations provide assistance. The panelists discussed the idea that, rather than closing areas to the public, government and nonprofits could work together to try to get them open and functioning again. A business continuity plan for a community is an important component of a disaster preparedness plan.

Several of the representatives of the nonprofit organizations emphasized the importance of education in resilience, from schoolchildren to people who have lived through multiple hurricanes. News people who report from the waterfront and the vows of elderly residents who have ridden out past hurricanes to remain in their homes can send the wrong messages. Public officials cannot risk putting anyone in danger. Education cannot be based just on fear but must empower individuals to care for themselves and others.

Better communications before a storm are essential, the panelists said. For example, an important advance would be to change the descriptions of storms, since wind speeds do not necessarily correlate with surge heights. For example, Hurricane Camille had stronger winds but a lower storm surge. More realistic warnings could generate more appropriate responses.

The panelists discussed the relevance of conveying postdisaster operations to people in a community before a disaster. For example, knowledge of the permissible and nonpermissible uses of disaster relief funds could contribute to ensuring the continued receipt of recovery funds. The provision of explicit and clear descriptions about eligible uses of funds was identified as a useful action that governments can take to support broad understanding of postdisaster operations.

The experience of Katrina taught several important lessons. For example, more hotels now allow pets, whereas during Katrina many people, including

many elderly people, did not want to leave their homes and leave their pets behind.

A major concern after disasters is the mental health of the people affected. Mississippi had a lack of mental health resources before the storm. Mental health providers and others, such as clergy, need skills in dealing with people after disasters.