Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects an estimated 10 million people worldwide and causes significant physical, emotional, and cognitive disabilities among those affected, including soldiers, veterans, and civilians. Conflicts in Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom [OIF]) and Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom [OEF]) have put members of the U.S. military at high risk for TBI, largely due to repeated and prolonged deployments, increasing injuries to the head and neck, and attacks with improvised explosive devices (IEDs) (Taber et al. 2006; Terrio et al. 2009). The high rate of TBI resulting from current combat operations directly impacts the health and safety of service members and their families and subsequently the level of troop readiness and retention. In addition, advances in life-saving measures have increased survival from TBI, leading to more individuals living with the consequences of these injuries. These advances include improved protective equipment, such as helmets and body armor; more responsive emergency care and improved medical evacuation systems; and innovations in treatment and care of TBI, such as better understanding of the effects of trauma and more sensitive and specific capabilities in diagnosing acute injury (Martin et al. 2008). Moreover, individuals living with TBI in military and civilian populations often require treatment for their condition. One form of treatment for TBI-related deficits is cognitive rehabilitation therapy (CRT), a systematic approach to functional recovery of cognitive or behavioral deficits and participation in related activities; however, the effectiveness of this treatment remains uncertain. Recognizing that TBI is the signature war wound of OIF/OEF and that there is a responsibility to care for individuals who serve in the military, the Department of Defense (DoD)

saw the need to ensure personnel have adequate treatment for wounds sustained in relation to military service. Therefore, DoD asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of CRT for TBI to guide its use and coverage in the Military Health System (MHS).

To complete its task, the IOM formed an ad hoc committee of experts from a range of disciplines to conduct a 15-month study aimed at evaluating the efficacy of CRT for TBI. The Committee on Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy for Traumatic Brain Injury (hereafter referred to as “the committee”) comprised members with expertise in epidemiology and study design, disability and long-term care, neurology, neuropharmacology, neuropsychology, nursing, psychiatry, psychology, rehabilitation medicine, and speech-language pathology. To address its Statement of Task (see Box 1-1), the committee developed a workplan and strategy for reviewing the evidence, including a comprehensive review of the literature on CRT for TBI. In addition to reviewing the literature, the committee conducted an assessment of recently completed or ongoing clinical trials; invited input from experts in the fields of cognitive rehabilitation research and practice, investigators of major research studies in both military- and civilian-related TBI, and advocates for the role of families and communities in providing ongoing support to injured members of the military and veterans; and received statements from stakeholders from various organizations and members of the public.

After reviewing the Statement of Task and meeting with a representative from the Department of Defense to clarify its intent, the committee interpreted its charge as assessing the state of the evidence. The committee acknowledges the goal of evidence assessments is to inform policy, upon which clinical practice guidelines are developed. Those at the Department of Defense are the only ones in position to make policy judgments for the Military Health System. After extensive deliberation, the committee determined it was beyond its charge to interpret its assessment of the evidence with respect to policy recommendations or clinical practice guidelines.

Over the course of the study, the committee met six times, engaged the public through two public workshops and participated in a number of ongoing activities organized by working groups. The committee did not complete an independent assessment of the treatment of TBI by cognitive rehabilitation within the MHS (subtask 5 of the Statement of Task). To accomplish this subtask, the committee determined it would need a substantial amount of data and submitted relevant questions as well as a request for data to the Department of Defense. The committee did not receive answers or data in response to the specific request. Due to constrained resources, including a lack of available data and time constraints, the committee was

A consensus committee shall design and perform a methodology to review, synthesize, and assess the salient literature and determine if there exists sufficient evidence for effective treatment using cognitive rehabilitation therapy (CRT) for three categories of traumatic brain injury (TBI) severity—mild, moderate, and severe—and will also consider the evidence across three phases of recovery— acute, subacute, and chronic. In assessing CRT treatment efficacy, the committee will consider comparison groups such as no treatment, sham treatment, or other non-pharmacological treatment. The committee will determine the effects of specific CRT treatment on improving (1) attention, (2) language and communication, (3) memory, (4) visuospatial perception, and (5) executive function (e.g., problem solving and awareness). The committee will also evaluate the use of multi-modal CRT in improving cognitive function as well as the available scientific evidence on the safety and efficacy of CRT when applied using telehealth technology devices. The committee will further evaluate evidence relating CRT’s effectiveness on the family and family training. The goal of this evaluation is to identify specific CRT interventions with sufficient evidence-base to support their widespread use in the MHS, including coverage through the TRICARE benefit.

The committee shall gather and analyze data and information that addresses

1. A comprehensive literature review of studies conducted, including but not limited to studies conducted on MHS or VA wounded warriors;

2. An assessment of current evidence supporting the effectiveness of specific CRT interventions in specific deficits associated with moderate and severe TBI;

3. An assessment of current evidence supporting the effectiveness of specific CRT interventions in specific deficits associated with mild TBI;

4. An assessment of (1) the state of practice of CRT and (2) whether requirements for training, education and experience for providers outside the MHS direct-care system to deliver the identified evidence-based interventions are sufficient to ensure reasonable, consistent quality of care across the United States; and

5. An independent assessment of the treatment of traumatic brain injury by cognitive rehabilitation therapy within the MHS if time or resources permit.

not able to complete the assessment. In addition, early in the course of the study, the Department of Defense indicated that completing this subtask was of lesser importance than other requirements in the Statement of Task.

In broad terms, TBI is an injury to the head or brain caused by externally inflicted trauma. DoD defines TBI as a “traumatically induced structural injury and/or physiological disruption of brain function as a result

of an external force” (see Box 1-2). TBI may be caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head, by acceleration or deceleration without impact, or by penetration to the head that disrupts the normal function of the brain (CDC 2010; Katz 1997; VA/DoD 2009). The events that lead to the trauma vary by population. Among civilians, motor vehicle accidents are the leading cause of TBI-related deaths; among young children and older adults, falls are a major cause of TBI (CDC 2010); and among soldiers and veterans, the most common source of TBI is a blast, followed by falls, motor vehicle accidents, and assault (DVBIC 2011).

In recent years, incidence of TBI has risen among the military population, as an all-volunteer force has been engaged in the longest war in U.S. history (OEF) and service members are exposed to longer and more frequent deployments. While in-theater, service members are increasingly attacked with more explosive weaponry. In 1991, during Operation Desert Storm, commonly referred to as the “first Gulf War,” approximately 20

BOX 1-2

Department of Defense Definition of Traumatic Brain Injury

A traumatically induced structural injury and/or physiological disruption of brain function as a result of an external force that is indicated by new onset or worsening of at least one of the following clinical signs immediately following the event:

• Any period of loss of or a decreased level of consciousness

• Any loss of memory for events immediately before or after the injury (i.e., posttraumatic amnesia [PTA])

• Any alteration in mental state at the time of the injury (confusion, disorientation, slowed thinking, etc.)

• Neurological deficits (weakness, loss of balance, change in vision, praxis, paresis/plegia, sensory loss, aphasia, etc.) that may or may not be transient

• Intracranial lesion

External forces may include any of the following events:

• Head being struck by an object

• Head striking an object

• Brain undergoing an acceleration/deceleration movement without direct external trauma to the head

• Foreign body penetrating the brain

• Forces generated from events such as blast or explosion, or other force yet to be defined

![]()

SOURCE: DoD 2007.

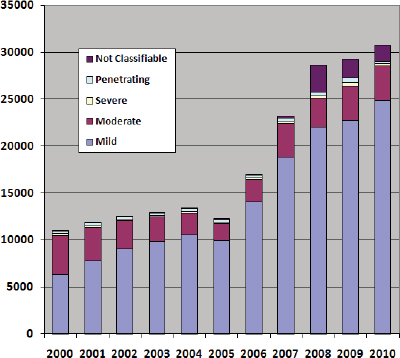

percent of treated wounds were head injuries (Carey 1996; Leedham and Blood 1992). Approximately 22 percent of wounded soldiers from OEF/OIF theaters have experienced wounds to the head, face, or neck (Okie 2005). From 2000 to 2010, the number of military service members diagnosed with TBI has nearly tripled (see Figure 1-1) (DVBIC 2011).

In 2000, 10,963 cases of TBI were diagnosed. Of these, 58 percent were mild, 38 percent were moderate, 2 percent were severe, 3 percent were penetrating, and the remainder not classifiable (< 1 percent). Chapter 2 provides information about the characteristics and definitions of mild, moderate, and severe TBI. In 2010, 30,703 TBIs were diagnosed, but a larger proportion were mild (81 percent) compared to 2000, followed by moderate (12 percent), severe (1 percent), penetrating (1 percent), and not classifiable (5 percent).

However, the actual annual incidence of TBI among service members is thought to be higher than currently estimated. Mild TBI, also called concussion, often goes underreported since recovery of consciousness is rapid and medical attention may not be sought. In addition, due to stigma associated with seeking medical treatment and appearing physically or psychologically vulnerable, or the desire to stay with their unit instead of leaving for treatment

FIGURE 1-1 Number of U.S. service members with TBI, by severity.

DATA SOURCE: DVBIC 2011.

or medical discharge, service members who need treatment may be hesitant to report or seek care for mild TBI or related symptoms. Perhaps for this reason, much more is known about the effects of moderate to severe TBI than mild TBI.

TBI is a major public health concern for civilians as well as members of the military. Each year, an estimated 1.7 million individuals in the United States sustain a TBI and either receive care in an emergency department, are hospitalized, or die from their injuries (Faul et al. 2010). Of those, approximately 52,000 individuals die each year from their injuries. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), each year an estimated 124,626 people with TBI experience long-term impairment or disability from their injury (CDC 2011). Overall, 75 percent of all TBIs occur among men, with higher rates among men than women across age groups. Very young children (0-4 years of age), adolescents (15-19 years of age), and older adults (> 65 years of age) are more likely to sustain TBI than other age groups (CDC 2011).

The consequences of TBI include short- and long-term effects, and often impact the individual’s family or primary caregiver as well. These effects may include disruptions to everyday life and work, changes in family and social functioning, and potentially burdensome financial costs. Recovering from TBI may be a slow, long, and painful process for individuals and their families, requiring unique medical, vocational, and rehabilitative therapy (Sayer et al. 2009; VA/DoD 2009). Symptoms of mild TBI may include

• Disorientation,

• Diminished arousal or alertness,

• Headaches,

• Dizziness,

• Loss of balance,

• Ringing in the ears,

• Blurred vision,

• Nausea or vomiting,

• Irritability or other changes in behavior or mood,

• Sensitivity to light or noise,

• Sleep disturbances, and

• Difficulty with attention/memory and other cognitive problems.

Individuals with moderate-severe TBI may show similar symptoms, but may also experience seizures, an altered level of consciousness, cranial nerve abnormalities, and paralysis or loss of sensation. With any severity of TBI, acute and persistent symptoms can have a profound impact on the survivor.

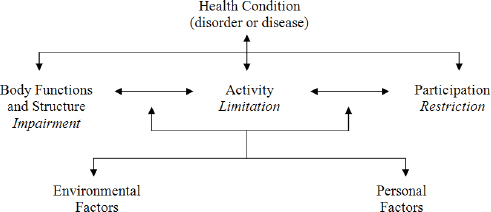

Biological and structural changes caused by TBI are far reaching and may lead to physical, emotional, and cognitive impairments (Cernak and Noble-Haeusslein 2010). Cognitive impairments resulting from TBI can affect multiple domains, including attention, language and communication, memory, visuospatial perception, and executive function.1 Cognitive impairments may limit activities of daily living (Temkin et al. 2009; Wise et al. 2010) and restrict participation in community, employment, recreation, and social relationships (Temkin et al. 2009). The extent of disability from cognitive impairment is shaped by many personal factors, such as age and cognitive reserve (Green et al. 2008), and environmental factors, such as family support (Sady et al. 2010). Chapter 3 provides a more in-depth description of the factors that may affect recovery.

Following a disabling illness or injury such as TBI, activity and participation may be increased by reducing impairments, modifying the environment, or both. These goals are part of rehabilitation strategies, including CRT, as depicted in the framework proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) (see Figure 1-2). The WHO-ICF framework recognizes impairments in body structures and functions (e.g., impaired memory) as a result of disease or injury, and limitations in activities and participation, i.e., the ability to carry out important daily activities (e.g., remembering weekly appointments) and the ability to participate in society (e.g., potential impact of the impairment on employment, home, school, or community). Importantly, activity and participation limitations result from an interaction between the person with impairment(s) and the physical and social environment. For example, an individual with TBI may have difficulty learning and remembering new information. With repeated training, she may be able learn some basic routines, such as writing appointments and

FIGURE 1-2 WHO-ICF Model of Disablement.

SOURCE: WHO 2001.

other important information down in her daily planner and consulting it frequently, allowing her to keep track of her schedule and other important tasks despite her memory impairment.

Determining the appropriate method and timing of treatment for an individual with TBI depends on a number of factors, including severity of injury, stage in recovery, and factors unique to the individual. At any stage of recovery, treatment success can be moderated by a number of factors including time since injury, etiology, and age. Some long-term consequences of TBI, such as seizures or depression, may not appear immediately after injury; likewise, the acute impairments may recover with or without treatment and rehabilitation, also known as spontaneous or natural recovery. Natural recovery typically occurs more quickly soon after injury and decelerates gradually over time, but the degree and duration of natural recovery is highly variable across individuals (Lovell et al. 2003). In general, the focus of treatment changes as a patient progresses from the acute/immediate phase after injury to more chronic stages of recovery. In the acute phase, treatment may primarily focus on increasing the patient’s survival while preventing or minimizing long-term consequences of injury and facilitating recovery (Meyer et al. 2010).

Once medically stable, those with more severe impairments may receive hospital or outpatient rehabilitation services typically focusing on overall return of activity and independence, as well as near-term necessities such as performing daily activities and mobility. As natural recovery slows in the subacute and chronic periods, rehabilitation typically narrows its focus to the areas likely to be persistent problems and to the specific activities of importance to the individual. Rehabilitation treatment may include a mixture of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. Nonpharmacologic treatments include, but are not limited to, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech-language therapy, and psychotherapy. Often, pharmacologic therapies supplement the overall rehabilitation program and aim to reduce specific impairments or effects of the injury. While no approved prescribed drug exists to treat the effects of TBI, many agents can be used to aid patients in their recovery. For example, patients who experience seizures may benefit from anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin, valproate), which allow patients to focus on recovery from existing impairments, unimpeded by intermittent and unpredictable seizures. Comorbid conditions such as pain, fatigue, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may present additional challenges and may also require pharmacologic intervention.

An earlier IOM report, Gulf War and Health, Volume 7 (IOM 2009), identified important causal and associative effects of both mild and moderate

to severe TBI on short- and long-term outcomes following injury. However, neither this report nor a recent IOM report on nutrients to support recovery following TBI, Nutrition and Traumatic Brain Injury: Improving Acute and Subacute Health Outcomes in Military Personnel (IOM 2011), examined the role of rehabilitation on recovery and outcome following mild or moderate to severe TBI.

Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy

The goal of CRT is to increase individuals’ ability to process and interpret information, thereby enhancing their capacity to function in everyday life. Treating individuals with cognitive deficits began early in the 19th century, as medical advancements allowed better understanding of cognitive processes and led to more individuals surviving previously life-ending events. The late 1970s ushered in the modern era of CRT, for the treatment of patients with acquired brain injuries, including those due to stroke, infection, multiple sclerosis, or traumatic injury. The therapy is a collection of treatments, generally tailored to individuals depending on the pattern of their impairments and activity limitations, related disorders (e.g., preexisting conditions or comorbidities), and the presence of a family or social support system. These factors all contribute to how, and perhaps how effectively, the treatment can be applied. CRT focuses on restoring impaired functions or compensating for residual impairments in areas such as attention, executive function, memory, and language or social communication, as well as the application or use of these functions during activities. Treatment may also include related comorbidities or secondary results of TBI. The application and practice of CRT varies in a number of ways, as described in Chapters 4 and 5.

CRT is offered in a wide array of settings, including rehabilitation hospitals, community-care centers, and individuals’ homes and workplaces. Due to the range of services offered, providers of cognitive rehabilitation also vary widely. They represent a number of fields and professions including rehabilitation medicine, nursing, physical therapy, speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, psychology, psychiatry, neuropharmacology, neuropsychology, and vocational rehabilitation. Moreover, members of these disciplines may deliver CRT services under disciplinary headings such as “physical therapy,” “occupational therapy,” or “counseling,” such that the correspondence between a treatment’s label and its contents is imprecise. While there has been some movement to standardize CRT, wide variations between expectations of practitioners from different professions still exist, reflecting how accreditation organizations separately determine educational and licensing requirements for practitioners within individual professions.

Due to the individualization of CRT, the appropriate timing and duration of the treatment is not known. These factors depend on the individual, severity of injury, and response to treatment, as well as health insurance coverage. The therapy may evolve throughout the course of treatment in response to feedback from the patient and caregivers. Although individualization is clinically useful, it presents challenges to researchers who attempt to study standardized CRT practices and discover what is effective, what could be improved, and what could be harmful to patients.

Assessments of the efficacy of CRT for TBI to date have utilized various methodologies and yielded mixed results. Systematic reviews published in peer-reviewed journals have generally found evidence for the benefits of CRT (Cicerone et al. 2000, 2005, 2011; Kennedy et al. 2008; Rohling et al. 2009). According to Cicerone et al. (2011), there is substantial evidence to support CRT for TBI, including interventions for attention, memory, language and communication, executive function, and for comprehensive (i.e., multi-modal or holistic) neuropsychological rehabilitation. A recent health care “technology assessment” (i.e., systematic review) commissioned by DoD found evidence of benefit from specific aspects of CRT, but generally found a small evidence base for the therapy, leading to inconclusive results about CRT’s efficacy (ECRI 2009). Ongoing needs for TBI survivors, especially service members and veterans cared for within the MHS, combined with inconsistent findings in prior evaluations of CRT for TBI, necessitated the current assessment. The literature evaluation is described in Part II of this report.

The MHS is the agency of the Department of Defense that provides health care for uniformed service members, military retirees, and their families. The VA health care system, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), is separate from the MHS; however, these two organizations share many common goals and characteristics.1 TRICARE is the MHS health care program for active duty personnel, military retirees, and family members of the seven uniformed services: the Army, the Air Force, the Navy, the Marine Corps, the Coast Guard, the Commissioned Corps of the Public

![]()

1 Individuals who formerly served in the military are “veterans.” Individuals who serve in the military for 20 years or more are “military retirees”; in some cases, those who are medically discharged from service prior to 20 years may qualify as military retirees. It is important to note that all former military members are veterans, but not all are military retirees. Military retirees and their dependents may access benefits through TRICARE, either through the direct care or purchased care systems. The military retiree may also access care through the VHA. Veterans who are not military retirees may be eligible for care through the VHA. In certain circumstances, the VHA may send a veteran for health care at an MHS or civilian facility (OPM 2009).

Health Service, and the Commissioned Corps of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, as well as the National Guard and Reserves. TRICARE is a single-payer system, encompassing direct care services at military treatment facilities and purchased care from civilian professional providers and health care services, suppliers, and facilities. In 2010, TRI-CARE served 9.4 million beneficiaries. Of these, 20 percent were active duty members of the various uniformed services, 26 percent were family members of an active duty member, and 54 percent were retirees and their families (TRICARE 2010).

The effects of TBI are felt within each branch of the service and throughout both DoD and the VA. In 1992, DoD and the VA collaborated to establish the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) to address the increasing incidence of TBI (DVBIC 2009). The DVBIC is specifically designed to provide services for active duty military, their beneficiaries, and veterans with TBI. It is a multi-site network of services, including clinical care, research initiatives, and educational programs. Since 2008, the DVBIC has also provided TBI surveillance and a registry of TBI survivors, as well as predeployment neuropsychological testing to service members. Ongoing and future research on acute and chronic recovery from TBI, including CRT, is facilitated through the DVBIC. Appendix C provides an overview of future and ongoing CRT clinical trials, including those sponsored through the DVBIC.

Current Coverage

Regarding the general subject of rehabilitation, TRICARE states coverage includes “any therapy for the purpose of improving, restoring, maintaining, or preventing deterioration of function. The treatment must be medically necessary and appropriate medical care. The rehabilitation therapy must be rendered by an authorized provider, necessary to the establishment of a safe and effective maintenance program in connection with a specific medical condition, provided at a skilled level and must not be custodial care or otherwise excluded from coverage (e.g., exercise or able to be provided at a non-skilled level)” (TRICARE 2010).

TRICARE does not state explicitly its coverage policy for CRT. In addition to coverage for rehabilitation generally, services such as speech, occupational, and physical therapy are provided; telemedicine is also covered under the policy. For speech therapy, TRICARE provides coverage when prescribed and provided or supervised by a physician to treat speech, language, and voice dysfunctions resulting from birth defects, disease, injury, hearing loss, and pervasive developmental disorders, with exclusions (e.g., TRICARE does not cover the following: disorders resulting from occupational or educational deficits, myofunctional or tongue thrust therapy,

videofluroscopy evaluation, maintenance therapy that does not require a skilled level after a therapy program has been designed, or special education services from a public educational agency to beneficiaries age 3 to 21). For occupational therapy, TRICARE covers therapy when prescribed and supervised by a physician to improve, restore, or maintain function, or to minimize or prevent deterioration of function. TRICARE covers physical therapy when prescribed by a physician and professionally administered to aid in the recovery from disease or injury by helping the patient attain greater self-sufficiency, mobility, and productivity through exercises and other modalities intended to improve muscle strength, joint motion, coordination, and endurance. Specific exclusions to physical and occupation therapy apply by region. In terms of telemedicine, TRICARE covers the use of interactive audio/video technology to provide clinical consultations and office visits when appropriate and medically necessary, including clinical consultations, office visits, and telemental health (e.g., individual psychotherapy, psychiatric diagnostic interview examination, and medication management).

According to a statement from TRICARE Management Activity, the organizing institution of TRICARE, CRT interventions for service members currently are available at medical treatment facilities through DoD’s supplemental health care program and through VA programs. Under the supplemental health care program, active duty service members may receive care that is excluded under TRICARE’s basic program if necessary to ensure adequate availability of health care services. DoD may also authorize reimbursements for CRT for service members or veterans under this supplemental program. However the therapy must be considered medically or psychologically necessary for the recovery of the injury and subsequent impairments for service members to receive these benefits.

TBI affects approximately 1.7 million people in the United States, and due to advanced lifesaving measures, more individuals are surviving their injuries and living with long-term disabilities. Among affected populations, members of the military and veterans, with their families, are impacted most (Faul et al. 2010). Given the rising burden of TBI and remaining questions regarding the efficacy of CRT, the goal of this report is to identify CRT interventions with sufficient evidence base to support widespread use in the MHS.

The remainder of the report is organized to inform the reader about unique aspects of TBI that may affect recovery; these aspects are described in relation to the injury (Chapter 2) and the specifics of the affected individual (Chapter 3). Chapter 4 describes the history and evolution of CRT,

including the current definitions endorsed by professional and research organizations; Chapter 5 describes the state of practice and the role of various providers. Chapter 6 details the committee’s methodology for reviewing the literature and making assessments about the quality of studies, as well as the hierarchy of evidence grading the committee used to make judgments. Chapters 7 through 12 provide the summary analysis of the evidence by cognitive domain, multi-modal/comprehensive CRT, and the therapy’s application through telehealth technologies. A discussion of possible adverse effects or harm is provided in Chapter 13. Chapter 14 discusses directions for research and clinical practice. The committee identified these directions throughout the report process, and many of the conclusions and recommendations in the final chapter aim to address the lack of methodological rigor among studies, while acknowledging the history of the therapy’s development, the unique features of the injury being addressed, and how future research may strive to compensate for these many challenges.

Carey, M. E. 1996. Analysis of wounds incurred by U.S. Army Seventh Corps personnel treated in corps hospitals during Operation Desert Storm, February 20 to March 10, 1991. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care 40(3S):165S–169S.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2010. What are the leading causes of TBI? http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/causes.html (accessed June 17, 2011).

———. 2011. Traumatic brain injury. http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/ (accessed June 17, 2011).

Cernak, I., and L. J. Noble-Haeusslein. 2010. Traumatic brain injury: An overview of pathobiology with emphasis on military populations. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 30(2):255–266.

Cicerone, K. D., C. Dahlberg, K. Kalmar, D. M. Langenbahn, J. F. Malec, T. F. Bergquist, T. Felicetti, J. T. Giacino, J. P. Harley, D. E. Harrington, J. Herzog, S. Kneipp, L. Laatsch, and P. A. Morse. 2000. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Recommendations for clinical practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 81(12):1596–1615.

Cicerone, K. D., C. Dahlberg, J. F. Malec, D. M. Langenbahn, T. Felicetti, S. Kneipp, W. Ellmo, K. Kalmar, J. T. Giacino, J. P. Harley, L. Laatsch, P. A. Morse, and J. Catanese. 2005. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 1998 through 2002. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 86(8):1681–1692.

Cicerone, K. D., D. M. Langenbahn, C. Braden, J. F. Malec, K. Kalmar, M. Fraas, T. Felicetti, L. Laatsch, J. P. Harley, T. Bergquist, J. Azulay, J. Cantor, and T. Ashman. 2011. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 2003 through 2008. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 92(4):519–530.

DoD (U.S. Department of Defense). 2007. Traumatic brain injury: Definition and reporting. Memorandum. HA Policy 07-030. Dated October 1, 2007. http://mhs.osd.mil/Content/docs/pdfs/policies/2007/07-030.pdf (accessed July 13, 2011).

DVBIC (Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center). 2009. About DVBIC. http://www.dvbic.org/About-DVBIC.aspx (accessed July 6, 2011).

———. 2011. DoD worldwide numbers for TBI: Total diagnoses. http://dvbic.org/Totals-at-a-Glance-(1).aspx (accessed June 17, 2011).

ECRI Institute. 2009. Cognitive rehabilitation for the treatment of traumatic brain injury. Plymouth Meeting, PA: ECRI Institute.

Faul, M., L. Xu, M. M. Wald, V. Coronado, and A. M. Dellinger. 2010. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: National estimates of prevalence and incidence, 2002–2006. Injury Prevention 16(Suppl 1):A268.

Green, R. E., B. Colella, B. Christensen, K. Johns, D. Frasca, M. Bayley, and G. Monette. 2008. Examining moderators of cognitive recovery trajectories after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 89(12 Suppl):S16–S24.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Gulf War and Health, Volume 7: Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2011. Nutrition and Traumatic Brain Injury: Improving Acute and Subacute Health Outcomes in Military Personnel. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Katz, D. I. 1997. Traumatic brain injury. In Neurologic Rehabilitation: A Guide to Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Planning. 1st ed. Edited by V. M. Mills, J. W. Cassidy, and D. I. Katz. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. Pp. 105–145.

Kennedy, M. R., C. Coelho, L. Turkstra, M. Ylvisaker, M. Moore Sohlberg, K. Yorkston, H. H. Chiou, and P. F. Kan. 2008. Intervention for executive functions after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review, meta-analysis and clinical recommendations. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 18(3):257–299.

Leedham, C. S., and C. G. Blood. 1992. A Descriptive Analysis of Wounds Among U.S. Marines Treated at Second Echelon Facilities in the Kuwaiti Theater of Operations. Ft. Belvoir: Defense Technical Information Center.

Lovell, M. R., M. W. Collins, G. L. Iverson, M. Field, J. C. Maroon, R. Cantu, K. Podell, J. W. Powell, M. Belza, and F. H. Fu. 2003. Recovery from mild concussion in high school athletes. Journal of Neurosurgery 98(2):296–301.

Martin, E. M., W. C. Lu, K. Helmick, L. French, and D. L. Warden. 2008. Traumatic brain injuries sustained in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Journal of Trauma Nursing 15(3):94–99.

Meyer, M. J., J. Megyesi, J. Meythaler, M. Murie-Fernandez, J. A. Aubut, N. Foley, K. Salter, M. Bayley, S. Marshall, and R. Teasell. 2010. Acute management of acquired brain injury part I: An evidence-based review of non-pharmacological interventions. Brain Injury 24(5):694–705.

Okie, S. 2005. Traumatic brain injury in the war zone. New England Journal of Medicine 19:2043–2047.

OPM (U.S. Office of Personnel Management). 2009. Guide to Processing Personnel Actions. Chapter 6—Creditable Service for Leave Accrual. http://www.opm.gov/Feddata/gppa/Gppa06.pdf (accessed October 29, 2009).

Rohling, M. L., M. E. Faust, B. Beverly, and G. Demakis. 2009. Effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: A meta-analytic re-examination of Cicerone et al.’s (2000, 2005) systematic reviews. Neuropsychology 23(1):20–39.

Sady, M. D., A. M. Sander, A. N. Clark, M. Sherer, R. Nakase-Richardson, and J. F. Malec. 2010. Relationship of preinjury caregiver and family functioning to community integration in adults with traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 91(10):1542–1550.

Sayer, N. A., D. X. Cifu, S. McNamee, C. E. Chiros, B. J. Sigford, S. Scott, and H. L. Lew. 2009. Rehabilitation needs of combat-injured service members admitted to the VA polytrauma rehabilitation centers: The role of PM&R in the care of wounded warriors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1(1):23–28.

Taber, K. H., D. L. Warden, and R. A. Hurley. 2006. Blast-related traumatic brain injury: What is known? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 18(2):141–145.

Temkin, N. R., J. D. Corrigan, S. S. Dikmen, and J. Machamer. 2009. Social functioning after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 24(6):460–467.

Terrio, H., L. A. Brenner, B. J. Ivins, J. M. Cho, K. Helmick, K. Schwab, K. Scally, R. Bretthauer, and D. Warden. 2009. Traumatic brain injury screening: Preliminary findings in a US Army brigade combat team. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 24(1):14–23.

TRICARE. 2010. Covered services: Rehabilitation. http://www.tricare.mil/mybenefit/jsp/Medical/IsItCovered.do?kw=Rehabilitation&x=14&y=12 (accessed July 6, 2011).

VA/DoD (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense). 2009. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline: Management of Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; Department of Defense.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: .

Wise, E. K., C. Mathews-Dalton, S. Dikmen, N. Temkin, J. Machamer, K. Bell, and J. M. Powell. 2010. Impact of traumatic brain injury on participation in leisure activities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 91(9):1357–1362.