Appendix B

Commissioned Papers

SUMMARY OF BACKGROUND DATA ON THE ECCE WORKFORCE

Michelle L. Maroto and Richard N. Brandon

Prepared for the IOM Committee on the ECCE Workforce

INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE

The National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (IOM) convened a Committee on the Early Childhood Care and Education Workforce, which is charged with holding a workshop to provide a clear definition of who is included in that workforce and to explore major issues regarding how to support the workforce and improve the quality of services it provides. A first step in that effort is to summarize the number and characteristics of the early childhood care and education (ECCE) workforce. This paper summarizes the currently available information about the number and characteristics of the ECCE workforce in the United States drawing mostly on published studies, tabulations from federal databases, and survey data compiled from multiple studies. Some previously unpublished data from several federal data sources provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics have been included.

The first challenge in this task comes from the lack of a uniformly accepted definition of the ECCE workforce, with many studies including

workers who are not within the relevant standard federal occupational definitions and excluding others who are paid for similar work. This paper takes the approach first developed by Brandon and Whitebook for estimating the number of ECCE workers,1 which treats any individual who is paid for the care and education of children age birth through five and not in kindergarten as a member of the ECCE workforce. The definition of ECCE workforce used is derived from focusing on the function of being paid to provide care or instruction for young children, regardless of the setting or program in which it occurs. This definition is consistent with the federal concept of what constitutes an occupation, which is independent of the location in which the occupation is carried out.

It is common to divide ECCE into three broad categories reflecting the type of setting in which care and instruction occur: center-based (including community-based centers, preschools, and Head Start programs); formal home-based or Family Child Care (FCC), in which “formal” refers to being available in the open market and often licensed or registered; and informal home-based or Family, Friend, and Neighbor (FFN) care, where there is a relationship between the child and caregiver and access is not broadly available in the community. However, there are not clear demarcations among these types of settings. Family Child Care homes are often expanded to include many children and several staff, and are not distinguishable from small centers; some FFN caregivers function as small businesses not clearly separable from FCC.

In all three settings, some care or instruction is provided by unpaid individuals, who are not normally considered part of a workforce. An appropriate estimate of the size of the workforce therefore requires the ability to distinguish between paid and unpaid care and instruction. Because of the overlap and presence of unpaid caregivers, these three categories therefore serve as useful descriptors, but do not clearly define who is or is not included in the ECCE workforce.

We were able to identify 50 relevant studies providing information regarding the size and characteristics of the ECCE workforce. This summary presents broad findings regarding the numbers and characteristics of the ECCE workforce as suggested by these 50 studies, plus additional characteristics derived from several federal data sources provided by Dixie Sommers and Theresa Cosca at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). A description of these studies and their citations may be found at the end of this summary report. Detailed matrices summarizing the find-

![]()

1 A. Burton, R. N. Brandon, E. Maher, M. Whitebook, M. Young, D. Bellm, and C. Wayne, Estimating the Size and Components of the U.S. Child Care Workforce and Caregiving Population (Center for the Child Care Workforce [CCW] and Human Services Policy Center [HSPC], May 2002).

ings from the national and state studies will be made available on the IOM project website.

Twenty-five of these studies used national samples, and the rest came from different state-level studies. Because comprehensive surveys of the ECCE workforce that use nationally representative samples are rare, we combine multiple studies in our summary to present a broad picture of workers. This picture is partial, and we acknowledge a need for more recent representative data about the ECCE workforce.

In this summary, we relied on recent studies that provided the best descriptive information about workers. Generally, state-level studies provided the most detailed information, but we refrain from including them in this summary paper because they are not necessarily representative of the U.S. population. Two reviews of state workforce studies found wide variation in the robustness of methodology employed2 and in the reported levels of such essential characteristics as educational attainment.3

Much of this summary is based on new, unpublished tabulations of federal workforce data reflecting federal occupation and industry codes used by the BLS and the Census Bureau. We requested these data because the most recent nationally representative surveys of the ECCE workforce were conducted between 10 to 20 years ago.

We also include characteristics of subsets of the ECCE workforce from more recent, but limited, studies when items of interest are not available from nationally representative sources. Most of the federal databases and studies on the ECCE workforce were lacking in different ways, which complicates the summary. What we present is therefore somewhat of a “pastiche,” combining the best available data from numerous sources to address key questions. We have excluded any data that we consider unreliable or unrepresentative.

Michelle Maroto of the University of Washington identified 50 relevant studies, which we have divided into seven categories reflecting their relative strength for describing the characteristics of the ECCE workforce on a national scale. In order to address study limitations, but still present characteristics of the ECCE workforce, we ranked each study based upon the representativeness of its sample and the types of workers and settings it covered. The sampling structure of studies ranged from nationally

![]()

2 G. Stahr-Breunig, R. N. Brandon, and E. J. Maher, “Counting the Child Care Workforce: A Catalog of State Data Sources to Quantify and Describe Child Caregivers in the Fifty States and the District of Columbia,” report to the Child Care Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, February 2004.

3 R. N. Brandon and I. Martinez-Beck, “Estimating the Size and Characteristics of the U.S. Early Care and Education Workforce,” in Critical Issues in Early Childhood Professional Development and Training, ed. M. Zaslow and I. Martinez-Beck (Brooks Publishing Company, 2005).

representative samples to multistate samples to state-level representative samples. The different settings of interest include center- and home-based care. In addition, studies used different language to refer to child care workers. Some studies divided child care workers into teachers, assistant teachers, and aids. Others only had divisions for center workers and FCC workers. Still others took a limited focus and only surveyed preschool teachers.

The studies summarized at the end of this report are categorized below; the number of studies in each category is shown in parenthesis:

I. Nationally representative; cover all children age B–5 (birth–age 5) and distinguish B–5 from school age; include most settings (2)

-

Profile of Child Care Settings (PCCS), 1990

-

National Households Education Survey (NHES); Human Services Policy Center (HSPC)/Center for the Child Care Workforce (CCW) Child Care Workforce Estimates Study, 2005

II. Nationally representative; include most settings; cover all B–5 but do not distinguish from school-age (7)

-

Current Population Survey (CPS), 2004

-

CPS; Occupation, 2010

-

CPS; Industry, 2010

-

American Community Survey (ACS); Occupation, 2009

-

ACS; Industry, 2009

-

Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), 2009

-

American Time Use Survey (ATUS); HSPC Estimating the Economic Value of Early Care and Education, 2005–2007

III. Nationally representative; cover a portion of B–5 workforce or settings; e.g., prekindergarten, Head Start (7)

-

Head Start Impact Study (HSIS), 2002–2006

-

Head Start: The Family and Child Experiences Survey (FACES), 2006–2007

-

Head Start: FACES, 2001

-

Head Start: FACES, 2000

-

Head Start: FACES, 1997

-

National Prekindergarten Study (NPS), 2003–2004

-

National Center for Early Development and Learning Survey (NCEDL-S), 1997

IV. Multistate; cover all of B–5 workforce by child age and setting (4)

-

National Child Care Staffing Study (NCCSS), 1988

-

Cost, Quality and Child Outcomes in Child Care Centers (CQCO), 1993

-

National Day Care Study (NDCS), 1976–1977

-

National Day Care Home Study (NDCHS), 1980

V. Multistate; cover portion of B–5 workforce and settings; e.g., prekindergarten (5)

-

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), 15 Months

-

NICHD SECCYD, 24 Months

-

NICHD SECCYD, 36 Months

-

Multi-State Study of Pre-Kindergarten (MSSPK), 2001

-

Statewide Early Education Programs Survey (SWEEP), 2001–2003

VI. Single state; cover all B–5 workforce (21)

VII. Single state; cover portion of B–5 workforce and settings; e.g., prekindergarten (4)

The first ranking tier includes studies that are: (1) nationally representative, (2) cover all child care workers for children birth through age 5, and (3) include most study settings. Within Tier I, the 1990 PCCS was the only study that was drawn from a nationally representative sample, covered child care workers for children birth through 5 years of age, and distinguished them from caregivers of school-aged children. It did not include the large FFN component of the workforce. However, this study was conducted in 1990, which makes it 20 years old and decreases its relevance for workers today. The HSPC analysis conducted in 2011 also meets these specifications, and includes the FFN component, but it only provides estimates of the size of the workforce and does not describe characteristics. Thus, we use the HSPC study for estimates of the size of the ECCE workforce, but rely on other studies to describe the characteristics of the workforce.

Most of the data presented in this report come from studies in the second category. This tier includes studies that are nationally representative and cover all child care workers for children birth through age 5, but do not distinguish these workers from those responsible for school-aged

children. Characteristics of child care workers provided by these studies come from Census occupational and industry classifications. We draw on previously unpublished tabulated data from the 2009 and 2010 CPS and the 2009 and 2010 ACS, and data from the HSPC demand-based estimate (Brandon et al., 2011), which used the 2005–2007 ATUS; this allowed identification of Family, Friend, or Neighbor caregivers. The application of federal occupation and industry codes in the surveys on which these studies were based allows us to report some descriptive information that is nationally representative. However, these data also include caregivers for school-aged children. We have only included such data where we do not think there is a likely systematic difference between the characteristics of caregivers of young children and those of school age.

The third tier consists of nationally representative studies that cover only a portion of the ECCE workforce. Thus, they yield information about some groups of child care workers and early education teachers, but not all of them. Some of the data come from the HSIS, which was conducted from 2002–2006 and the Head Start: FACES surveys from 1997 through 2001. Teachers and assistant teachers in these studies were all recruited from Head Start classrooms. This tier also includes the NPS and the NCEDL-S. Both of these studies only surveyed prekindergarten teachers and are thus restricted to children between ages 3 and 5. It should be noted that due to federal and state prekindergarten program standards, the educational level of the prekindergarten workforce reflected in these studies is higher than for the ECCE workforce in general.

The fourth tier consists of multistate studies that cover all of the B–5 child care workforce. Multistate studies often attempted to approximate a nationally representative sample by surveying workers in a diverse subset of states, but none has a sufficient number of states to effectively represent all regions of the United States. The 1988 NCCSS surveyed center workers in five cities (Atlanta, Boston, Detroit, Phoenix, and Seattle). The 1993 CQCO surveyed staff in 400 programs across four states (California, Colorado, Connecticut, and North Carolina). The 1976–1977 NDCS was constructed from state licensing lists and thus systematically under-represents unlicensed settings and providers in states that only require licensing of a small fraction of providers. The 1980 NDCHS consists of both regulated and unregulated family day care homes in three urban areas (Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and San Antonio). Most of these studies are older; therefore, we do not include much information from them in this report.

The fifth tier consists of multistate studies that cover only a portion of the ECCE workforce. The NICHD SECCYD at 15, 24, and 36 months surveyed caregivers for children in the NICHD study when the children were 15, 24, and 36 months old and thus excluded workers caring only

for children above that age. The 2001 MSSPK and the 2001–2003 SWEEP were both conducted by the National Center for Early Development and Learning (NCEDL). The MSSPK is based on a stratified random sample of teachers in state-funded prekindergarten classrooms from six states (California, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, New York, and Ohio). The SWEEP was based on state-funded prekindergarten classrooms from five states (Massachusetts, New Jersey, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin).

The sixth and seventh tiers contain 25 single-state studies from 15 states at different time periods. We do not discuss these data in this summary, but these studies are included in the detailed data matrices. The detailed matrices provide the findings from these studies in much richer detail and discuss the nature of the studies, indicating their strengths and weaknesses for this purpose (which may not have been the primary purpose for which the studies were conducted). The print matrices provide an overview of this information, but the digital file includes estimates for each of the individual studies.

COUNTING THE ECCE WORKFORCE FOR CHILDREN AGE B–5, BY SETTING

The only study that encompassed and distinguished the workforce responsible for children B–5 and included all settings (center-based, formal home-based, and informal home-based) was the HSPC demand-based estimate (Brandon et al., 2011). This study updated and refined earlier work led by Brandon and Whitebook (CCW and HSPC, 2002). This approach is labeled demand-based because the essential data are derived from one of several large scale, nationally representative surveys that ask parents how many hours in a typical week each of their children spends in each type of non-parental care setting, including both formal and FFN care; and whether the care and instruction is paid or unpaid. The National Household Education Survey, Early Childhood Supplement (2005) was deemed most appropriate because it contains the most comprehensive and well-differentiated set of categories for type of care. It also asks parents the child:adult ratio for the setting where their child is in care. The demand-based estimate combines hours per child in care, child:adult ratios and average hours worked by ECE staff (from BLS Current Employment Statistics) to derive the full-time equivalent (FTE) number of adults caring for young children. Because the estimates are derived from samples of individual children with such known characteristics as age, it is possible to divide the workforce by such variables as the age of child and setting. Various other adjustments are made to convert FTEs to individuals and estimate the number of directors and other staff positions associated with that number of caregivers.

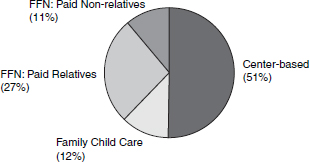

FIGURE B-1 Demand-based estimates of the ECCE workforce.

TABLE B-1 Formal ECCE Workforce by Role/Responsibility

| Total Persons in Typical Week |

Center-Based Staff | FCC Staff | ||||

| Center Staff: Total |

Directors/ Administrators |

Teachers |

Assistant Teachers and Aides |

FCC Providers |

FCC Assistants |

|

| 1,333,000 | 1,083,000 | 83,000 | 564,000 | 435,000 | 151,000 | 99,000 |

NOTE: ECCE: Early Childhood Care Education; FCC: Family Child Care.

SOURCE: HSPC demand-based estimates. Brandon et al., 2011.

These demand-based estimates are illustrated in Figure B-1. It should be noted that in addition to the 2.2 million paid ECCE workers shown here, the same estimates indicate an additional 3.2 unpaid workers, for a total caregiving population of 5.5 million.

Table B-1 provides a differentiation of the formal components of the ECCE workforce by role or responsibility. The FFN component is not shown because such a differentiation is not relevant.

An advantage of the demand-based approach is that it differentiates by the age of children served as well as by type of setting, as shown in Table B-2. It is useful to differentiate by age of children since different skills and orientations may be required to best meet children’s needs.

Differentiation by Occupation and Industry: BLS and Census Bureau Employment Data

The demand-based workforce estimates in the previous section have the advantages of covering all components of the ECCE workforce and

TABLE B-2 Estimated Number of Paid ECCE Workers in the United States in a Typical Week by Setting and Age of Child

| Total Paid | Center Care | FCC Providers |

Paid Relatives | Paid Non-Relatives | |

| Infants (0–18 mos.) | 490,000 | 223,000 | 78,000 | 111,000 | 78,000 |

| Toddlers (19–36 mos.) |

654,000 | 309,000 | 92,000 | 166,000 | 87,000 |

| Early Head Start | 13,000 | 13,000 | |||

| Private preschoolers (3–5 yrs) | 826,000 | 371,000 | 80,000 | 312,000 | 63,000 |

| Public preschoolers (3–5 yrs) | 79,000 | 79,000 | |||

| Head Start | 94,000 | 94,000 | |||

| All 0–5 year olds | 2,157,000 | 1,088,000 | 250,000 | 589,000 | 229,000 |

NOTE: FCC: Family Child Care.

SOURCE: HSPC demand-based estimates. Brandon et al., 2011.

of being restricted to caring for or instructing children age B–5. However, these estimates have many limitations. They can only be conducted at broad intervals when a demand survey is available. They also entail great uncertainty because they must link many different estimates from different data sources. Because they do not directly interview employees or employer, they lack many essential features included in standard federal workforce data such as the sector or industry in which they are employed, the number of hours worked, wages earned, separation or turnover rate. They also lack the educational and demographic characteristics of members of different occupations collected by the Census Bureau using the same federal occupational classification. In this section, and in Tables B-3A and B-3B below, we draw on relevant federal workforce data from the BLS to complete this initial portrait. In the next major section of the paper, we summarize studies using Census data to provide additional characteristics.

There are many challenges to using standard federal data from the BLS and the Census Bureau to describe the ECCE workforce, as discussed in Federal Data Sources for Understanding the Early Childhood Care and Education Workforce: A Background Paper, a second commissioned work

included in this report. The primary challenge is that for the largest share of the ECCE workforce, the federal occupational categorization does not differentiate between those employed to provide care and instruction to young children (B–5) and those responsible for school-aged children. However, there are several relevant pieces of data for which there is no particular reason to assume a different distribution of characteristics related to the age of children in care. It is therefore useful to examine those data, keeping in mind this caveat.

Relating ECCE Occupations and Industries

A particular advantage of the federal data system is that it cross-tabulates occupations with the industries or economic sectors in which they are employed. We can thus see that ECCE does not function as an isolated bubble in the U.S. economy, but is highly interwoven with other sectors. Tables B-3A and B-3B are based on BLS employment statistics, as opposed to the demand-based estimates shown in Tables B-1 and B-2. We also compare the size of the ECCE workforce as indicated by each of these sources.

Comparing BLS Employment Estimates to Demand-Based Estimates

As seen in Table B-3A, BLS identified 1.8 million jobs, of which 1.3 million are classified as child care workers and 0.5 million as preschool teachers.

The demand-based estimate exclusive of FFN caregivers was about 1.4 million. Because the BLS estimate of 1.8 million includes caregivers for school-aged children, it would be expected to be larger than the demand-based estimate for children under age 6. If, for example, one-third of child care workers identified by the BLS are working with school-aged children, that would reduce the 1.8 million to 1.3 million. The two estimates are therefore roughly similar for the components of the ECCE workforce that they share.

However, because the BLS estimate probably does not include most of the 0.8 million paid FFN workers in the demand-based estimate, it is reasonable that the 1.8 million is lower than the 2.2 million total in the demand-based estimate. If the 0.8 million demand-based estimate of paid FFN workers is added to the 1.3 million derived from assuming one-third of child care workers care only for school-aged children, the adjusted total would be 2.1 million, roughly comparable to the demand-based estimate of 2.2 million.

Industries Employing ECCE Workers

Of the 1.8 million employees reported by the BLS, 75 percent or 1.3 million are wage and salary employees, and the remaining 431,000 are self-employed, presumably as FCC proprietors. About 247,000 of the wage and salary employees are employed in private households. This estimate could include nannies and some paid FFN caregivers. Subtracting this number from the total wage and salary employees leaves a subtotal of 631,000 individuals who are employed out of the home, plus an additional 390,000 preschool teachers.

The balance between wage and salary and self-employment varies substantially between those classified as child care workers and those as preschool teachers. Almost a third of the child care workers are self-employed, compared to less than 2 percent of preschool teachers.

The industries employing child care workers and preschool teachers are quite different. Of interest is that only about 66,000 or 15 percent of preschool teachers work in public or private schools. More than two-thirds—69 percent—are in social assistance establishments. Presumably Head Start teachers who are employed by community-based contractors are considered social assistance employees.

Within the 631,000 child care workers whose employment is not home-based, the greatest number—253,000—work in child care services, what are commonly thought of as child care centers. But these workers comprise less than a third of such employees.

Child care workers are distributed across a wider range of economic sectors than preschool teachers. About 21 percent are in social assistance; 4 percent in health care, mostly residential facilities; 19 percent are in child day care services, such as community-based centers; 3 percent are in fitness and recreation centers, and 6 percent work for “religious, grantmaking, civic, professional, and similar organizations,” which are presumably centers operated by such entities. Less than 1 percent are in transportation (including school-bus drivers) and hotel or motel accommodations.

Almost 50,000 are employed in “residential care facilities,” of which the largest number—17,000—are in mental health, mental retardation, and substance abuse facilities. However, we cannot determine whether these workers are responsible for young children of parents residing in such facilities, for adolescent residents, or a combination of the two. This is one of the challenges of not differentiating child care workers by the age group of children served. Because such residential facilities are categorized within the health sector, they would not normally be identified as related to ECCE if the occupations were not specified within the sector.

This brief summary illustrates the value of the BLS system of relating occupations to industries. It allows policy makers to consider both how many employees there are and where they are employed. If large-scale

TABLE B-3A Employment by Occupation and Industry, 2008

| Child Care Workers | |||

| 2008 | |||

| Industry | Employment (thousands) | Percentage of Occupation | |

| Total employment, all workers | 1,301.9 | 100.00 | |

|

Self-employed and unpaid family workers, all jobs |

424.0 | 32.57 | |

| Total wage and salary employment | 877.8 | 67.43 | |

|

Transportation and warehousing (school and employee bus transportation) |

11.6 | 0.89 | |

| Educational services, public and private | 147.7 | 11.34 | |

| Health care and social assistance | 334.2 | 25.67 | |

| Health care | 57.3 | 4.40 | |

|

Residential care facilities (mental retardation, mental health, substance abuse, other) |

49.5 | 3.80 | |

| Social assistance | 276.9 | 21.27 | |

|

Individual, family, community, and vocational rehabilitation services |

23.2 | 1.79 | |

| Child day care services | 253.7 | 19.48 | |

|

Arts, entertainment, and recreation (including fitness and recreation centers) |

34.9 | 2.68 | |

|

Amusement, gambling, and recreation industries |

34.8 | 2.68 | |

|

Accommodation (hotels, motels) and food services |

1.0 | 0.08 | |

|

Other services (except government and private households) |

77.9 | 5.99 | |

|

Religious, grantmaking, civic, professional, and similar organizations |

77.5 | 5.96 | |

| Government | 17.6 | 1.35 | |

| Private households; all jobs | 246.5 | 18.93 | |

NOTE: CC: Child Care.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Projections, 2009.

quality improvement efforts are being planned, then knowing which establishments employ how many workers is essential.

Employment Projections

Obviously, if policy makers are looking to provide supports and incentives for professional development and quality improvement, locating the

| Preschool Teachers | CC Workers + Pre-K | ||

| 2008 | 2008 | ||

| Employment (thousands) |

Percentage of Occupation |

Employment (thousands) |

Percentage of Occupation |

| 457.2 | 100.00 | 1,759.1 | 100.00 |

| 7.0 | 1.53 | 431.0 | 24.50 |

| 450.2 | 98.47 | 1,328.0 | 75.49 |

| 11.6 | 0.66 | ||

| 66.3 | 14.51 | 214.0 | 12.17 |

| 317.3 | 69.40 | 651.5 | 37.04 |

| 2.8 | 0.62 | 60.1 | 3.42 |

| 0.5 | 0.10 | 50.0 | 2.84 |

| 314.5 | 68.78 | 591.4 | 33.62 |

| 17.4 | 3.81 | 40.6 | 2.31 |

| 297.1 | 64.97 | 550.8 | 31.31 |

| 0.7 | 0.16 | 35.6 | 2.02 |

| 0.6 | 0.13 | 35.4 | 2.01 |

| 1.0 | 0.06 | ||

| 58.5 | 12.80 | 136.4 | 7.75 |

| 58.5 | 12.80 | 136.0 | 7.73 |

| 5.5 | 1.19 | 23.1 | 1.31 |

| 0.3 | 0.07 | 246.8 | 14.03 |

places that employ workers is essential to arranging supports. Planning for both pre-service and in-service professional development, as well as for recruitment activities, is aided by projecting future job growth in different occupations and industries. BLS creates projections regularly for all occupations and industries, considering a variety of economic trends and factors. Table B-3B summarizes the BLS employment projections for

TABLE B-3B Projected Employment by Occupation and Industry, 2018

| Child Care Workers | |||

| 2018 | |||

| Industry | Employment (thousands) |

Percentage Change |

|

| Total employment, all workers | 1,443.9 | 10.91 | |

|

Self-employed and unpaid family workers, all jobs |

445.0 | 4.93 | |

|

Total wage and salary employment |

999.0 | 13.80 | |

|

Transportation and warehousing (school and employee bus transportation) |

13.9 | 19.83 | |

|

Educational services, public and private |

180.3 | 22.12 | |

|

Health care and social assistance |

375.2 | 12.27 | |

| Health care | 63.1 | 10.24 | |

|

Residential care facilities (mental retardation, mental health, substance abuse, other) |

54.1 | 9.40 | |

| Social assistance | 312.1 | 12.69 | |

|

Individual, family, community, and vocational rehabilitation services |

28.0 | 20.44 | |

|

Child day care services |

284.1 | 11.98 | |

|

Arts, entertainment, and recreation (including fitness and recreation centers) |

39.8 | 14.23 | |

|

Amusement, gambling, and recreation industries |

39.8 | 14.22 | |

|

Accommodation (hotels, motels) and food services |

1.1 | 7.75 | |

|

Other services (except government and private households) |

88.5 | 13.58 | |

|

Religious, grantmaking, civic, professional, and similar organizations |

88.0 | 13.54 | |

| Government | 19.0 | 8.12 | |

|

Private households; all jobs |

273.3 | 10.88 | |

NOTE: CC: Child Care

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Projections, 2009.

ECCE workers, which incorporate both child care workers (which include school-aged care) and preschool teachers.

We examine ECCE employment by industry or sector because BLS projects employment growth at different rates for sectors reflecting

| Preschool Teachers | CC Workers + Pre-K | ||

| 2018 | 2018 | ||

| Employment (thousands) |

Percentage of Occupation |

Employment (thousands) |

Percentage of Occupation |

| 543.9 | 18-95 | 1,987.8 | 13.00 |

| 7.4 | 5.50 | 452.4 | 4.97 |

| 536.5 | 19-16 | 1,535.5 | 15.63 |

| 13.9 | 19.83 | ||

| 72.7 | 9.53 | 253.0 | 18.22 |

| 388-9 | 22.56 | 764.1 | 17.28 |

| 3.3 | 17-65 | 66.4 | 10.48 |

| 0.5 | 9-96 | 54.6 | 9.20 |

| 385-6 | 22.60 | 697.7 | 17.97 |

| 20.7 | 19-18 | 48.7 | 19.95 |

| 364.8 | 22.80 | 648.9 | 17.81 |

| 0.8 | 16.18 | 40.6 | 14.04 |

| 0.7 | 14-95 | 40.5 | 14.41 |

| 1.1 | 10.00 | ||

| 66-1 | 12.94 | 154.6 | 13.34 |

| 66-1 | 12.94 | 154.1 | 13.31 |

| 5-9 | 8.10 | 24.9 | 7.79 |

| 0.3 | 4.43 | 273.6 | 10.86 |

trends in the economy. Thus, the overall number of jobs for child care workers plus preschool teachers is projected to grow about 13 percent over a decade from 2008 to 2018. Within that overall projection, preschool employment is projected to grow 19 percent and child care employment

11 percent. Wage and salary employment is projected to grow 16 percent, and self-employment only 5 percent. Similarly, child day care employment in centers is projected to grow by 12 percent, but employment in fitness and recreation centers by 14 percent. The greatest projected growth—22 percent—is for child care workers in the educational services sector; employment of preschool teachers in educational establishments is projected to grow by 10 percent.

These are of course projections, and changes in economic trends, professional practice, or public policies could yield different results. Because the classification that differentiates child care workers from preschool teachers is not consistent with current professional concepts in the field of early care and education, the differences between these two occupations are likely to vary.

Injuries and Illnesses Involved in Missing at Least One Day of Work4

The annual rate of illnesses and injuries for child care services (including workers responsible for school-aged children) is somewhat higher than the national average (115 per 10,000 full-time workers versus 106 for all U.S. workers). The child care rate is much higher than that for elementary–secondary education (115 vs. 60 per 10,000 workers).

The rate of illness and injury for child care services has increased in the last 2–3 years, while the overall national rate has not, and the educational services rate has declined. However, the year-to-year variability may be due to reflecting a relatively small sample of child care workers. BLS staff has advised us that the data cannot be averaged across years to provide a more stable estimate.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ECCE WORKFORCE

We compiled data regarding the characteristics of the ECCE workforce from the 50 studies described above and describe the workforce using these characteristics and the relative study rankings. In this summary we gave preference to studies based upon their (1) representativeness of the population, (2) coverage of the ECCE workforce, and (3) year of data collection. Thus, the contents of each of the tables in this report are primarily based upon the second set of studies (II). These studies are nationally representative, include most child care settings (except FFN), cover all B–5 caregivers, but do not distinguish them from caregivers of

![]()

4 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) runs provided 02-13-11. Occupational injury and illness data from the BLS Occupational Safety and Health Statistics program. Program information available at http://www.bls.gov/iif/.

school-aged children because they use Census occupational and industry codes.

We have added to these studies relevant data from two Census sources—the 2009 ACS and the 2010 CPS, which were specially tabulated for this study by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.5 These tabulations reflect application of the occupation and industry codes cited here.

The occupations used in these analyses are based on the two following broad federal occupational codes:

-

2300: Preschool and kindergarten teachers

-

4600: Child care workers

The industries used in these analyses are based on the two following federal industry codes:

-

8470: Child day care services

-

9290: Private households (broader Census code that includes FCC providers)

Thus, the data reflect a somewhat broader workforce definition than the B–5 focus of the ECCE committee, because child care workers (4600) include care for school-aged children and the private households industry code (9290) includes other household workers beyond FCC providers. However, they do not include the sizeable FFN component, because most FFN caregivers do not identify themselves as in the child care occupation. When data are not available from this set of studies, we use additional studies reviewed for this report.

The first column of each table indicates the type and study ranking (I–VII) and the number of studies in this type. The additional columns provide estimates for child care providers, preschool teachers, directors, and FCC providers. The child care worker data in the first column of each table do not necessarily reflect the specific total of the characteristics by position (child care worker, preschool teacher, or FCC provider). Rather, they are independent estimates calculated by the cited studies for U.S. Census occupational codes. In some cases we report the combination of preschool and kindergarten teachers, because Census data do not distinguish these categories. From BLS data, which do use this distinction, we know that about two-thirds of the combined category is preschool

![]()

5 U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Previously unpublished tabulations from the CPS (2010) and ACS (2009) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. These tabulations were from the PUMS files, which are a sample of the full microdata set. Personal communication with Dixie Sommers, assistant commissioner, February 11, 2011.

teachers, so the combined data are more reflective of preschool than kindergarten teachers.

Characteristics are divided into seven major areas:

-

Demographic characteristics: age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and household composition and income

-

Qualifications: educational attainment, general and early childhood education (ECE)-specific, ECE experience, and bi- or multilingual communication

-

Professional development: training and credentials

-

Labor market characteristics: full-/part-time employment, hours worked per week, other employment

-

Compensation: wages, benefits

-

Staff stability: occupational and job turnover

-

Professional status: attitudes and orientation: union and professional organization membership

We describe each set of these characteristics below and present more detailed summaries of the studies included in a later section of this report. Detailed tables of characteristics of the ECCE workforce are available at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/The-Early-Childhood-Care-and-Education-Workforce-Challenges-and-Opportunities.aspx.

Demographic Characteristics: Age, Gender, Race/Ethnicity, Marital Status, Household Composition and Income

Age of Workers

According to previously unpublished tabulations based on data from the CPS and the ACS, the median age for child care workers ranges from 35 to 39 years. The median age for preschool teachers is 39 years, but the median age for workers employed in private households, which include FCC providers, is higher—43 years.

The share of the workforce that may be considered adolescent baby-sitters has been an issue of interest. Across the studies, the percentage of caregivers under age 20 ranges from 5 to 9 percent. The percentage is highest for FCCs (about 7 percent) and lower for preschool teachers (<2 percent). The percentage of caregivers aged 65 years or older is also small, ranging from 4 to 5 percent. Table B-4 shows the median age of ECCE workers.

TABLE B-4 Median Age of Workers, 2009–2010

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers* | FCC Providers |

| (II) 3 | 35–39 | 39 | 43 |

NOTE: FCC: Family Child Care.

* Census categories combine preschool and kindergarten teachers.

SOURCES: Unpublished tabulations of data from the CPS (2010) and the ACS (2009). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2011.

TABLE B-5 Percentage Female in Workforce, 2009–2010

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers | FCC Providers |

| (II) 5 | 94.2–95.2 | 97.0–97.9 | 90.9–91.0 |

NOTE: FCC: Family Child Care. Data in this table reflect standard federal occupational and industry codes. Groups are not subsets of each other.

SOURCE: Unpublished tabulations of data from the CPS (2010) and the ACS (2009). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2011.

Gender

As shown in Table B-5, about 95 percent of the ECCE workforce is female. The percentage of women is highest for preschool and kindergarten teachers (97 percent).

Race/Ethnicity

Table B-6 shows data regarding the race and ethnicity of ECCE workers. The child care workforce is predominately white and non-Hispanic, with estimates ranging from 71 to 79 percent white for child care workers, 76 to 83 percent for preschool teachers, and 69 to 86 percent for FCC providers. A large minority of FCC providers (36 to 40 percent) are of Hispanic origin.

Additional comparisons of the race and ethnicity of child care workers with children age B–5 are available from the HSPC demand-based estimates study (Brandon et al., 2011), which used data from the ATUS. However, this summary does not include preschool teachers because they are not included in the Census occupational code for child care workers

TABLE B-6 Race/Ethnicity of Workers, 2009–2010

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers | FCC Providers | |

| White, non-Hispanic (%) | (II) 5 | 70.5–78.6 | 75.6–82.7 | 69.3–85.5 |

| African American, non-Hispanic (%) | (II) 5 | 15.8–18.0 | 13.4–16.5 | 8.7–10.1 |

| Hispanic/Latina (%) | (II) 5 | 16.2–19.1 | 9.6–11.4 | 35.5–39.5 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native (%) | (III) 2 | 0.9 (1997)–1.2 (2006) | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander (%) | (II) 2 | 2.6–2.9 | 2.2 | 3.4 |

| Multiracial/biracial, other (%) | (II) 5 | 5.0–10.4 | 3.9–5.7 | 5.9–17.2 |

NOTE: FCC: Family Child Care. CPS and ACS data in this table reflect standard federal occupational and industry codes. Groups are not subsets of each other.

SOURCE: Except for estimates for percentage American Indian or Alaskan Native, which come from the Head Start FACES, data come from unpublished tabulations of data from the CPS (2010) and the ACS (2009). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2011.

and could not be distinguished from kindergarten teachers.6 As Table B-7 shows, when averaging data from 2005 through 2007, the estimates for the race/ethnicity of child care workers are similar to those above. The percentage of child care workers who are white (75.9 percent) is very close to the percentage of children ages B–5 who are white (76.5 percent). However, there are some small differences in the percentage of workers and children who describe their racial group as black, other, and Hispanic. Averaging data from 2005 through 2007, 17.4 percent of child care workers identified as black, 6.7 percent as a racial group not listed (other), and 17.8 percent as Hispanic. In the same time period, 14.8 percent of children ages B–5 were identified as black, 8.8 percent as other, and 22.3 percentage as Hispanic. The large percentage of young children who were Hispanic reflects the growing Hispanic population in the United States. It is possible that this summary overstates the share of the ECCE workforce from

![]()

6 Within the ATUS sample, 343 respondents (318 females and 25 males) listed their industry or occupation as child care worker. The industry code used for this analysis was 8470—child care day services—and the occupation code was 4600—child care workers. This sample is restricted to employed persons, but it did not have any other restrictions. This study did not use industry or occupation codes to define FFN caregivers. Caregiving was based on time spent in non-household childcare activities.

TABLE B-7 Race/Ethnicity for Child Care Workers and Children, 2005–2007 Average

| Child Care Workers | Children Ages Birth–5 | ||

| Percent | Percent | ||

| White | 75.9 | White | 76.5 |

| Black | 17.4 | Black | 14.8 |

| Other | 6.7 | Other | 8.8 |

| Hispanic | 17.8 | Hispanic | 22.3 |

SOURCE: HSPC demand-based estimates. Brandon et al., 2011.

minority groups. That is because the non-included preschool teachers are likely to have a greater share of white and smaller share of other racial/ ethnic backgrounds, because they often have higher formal education requirements, and the rate of college attendance is substantially higher for whites.

Marital Status

Almost half (48 percent) of the total child care workers are married, with another third (33 percent) that have never been married, and almost a fifth (18 percent) who indicate that they are separated, widowed, or divorced, as shown in Table B-8.

Household Composition and Income

About two-thirds of child care workers have children present in their homes. A minority live alone (16–22 percent) or live with their parents (19–24 percent). The mean household income for a child care worker in 1993 was $26,835, which translates to approximately $40,495 in 2010 dollars. The mean household income for a preschool teacher in 2004 was

TABLE B-8 Marital Status of Child Care Workers, 2007

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | |

| Married (%) | (II) 1 | 48.3 |

| Never married (%) | (II) 1 | 33.3 |

| Formerly married (%) | (II) 1 | 18.4 |

SOURCE: HSPC demand-based estimates. Brandon et al., 2011.

TABLE B-9 Household Composition and Income

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool Teachers | |

| Children present in household (%) | (II) 1 | 68.3 (2007) | |

| Mean household income (dollars) | (III) 1; (IV) 1 | 26,835 (1993) | 58,388 (2004) |

| Median household income (dollars) | (III) 1 | 52,000 (2004) |

SOURCE: Estimates for the percentage child care workers with children present come from HSPC demand-based estimates. Brandon et al., 2011. Estimates for the mean household income of child care workers come from the CQCO, 1993. All other estimates come from the NPS, 2004.

$58,388, which translates to $67,579 in 2010 dollars. The median household income in 2004 was $52,000, which is equivalent to $60,185 in 2010 dollars. These data are presented in Table B-9.

The estimates for prekindergarten teachers in this table come from the NPS, which only sampled teachers of 3–4-year-olds. Preschool and prekindergarten teachers have higher compensation than other child care workers, and are therefore likely to have higher family incomes. It should be noted that 30 percent had incomes that are considered to be below the criterion for self-sufficiency, which is below twice the federal poverty level.

Qualifications: Educational Attainment—General and ECE-Specific, Professional Development, ECCE Experience, and Bi- or Multilingual Communication

Many of the studies we reviewed focused on assessing child care workers’ qualifications and subsequently determining whether qualifications were correlated with quality of care. For this reason, there is a large amount of information on education attainment, early care and education training, and other types of professional development on the national and state level. However, few of the national studies, except those focused on preschool, restricted their samples to child care workers for B–5 children. The estimates summarized in Table B-10A come from provided tabulations of Current Population Survey data, which includes caregivers for school-aged children. The estimates summarized in Table B-10B come from the FACES studies and the MSSPK and SWEEP studies that only focused on prekindergarten teachers.

TABLE B-10A Educational Attainment, 2009–2010

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | FCC Providers | |

| a. High school diploma or equivalent (%) | (II) 6 | 26.7–33.2 | 32.2–33.4 |

| b. Some college (%) | (II) 5 | 21.4–39.0 | 17.3–32.0 |

| c. Associate’s degree (%) | (II) 6 | 7.3–12.1 | 5.1–5.6 |

| d. Bachelor’s degree (%) | (II) 6 | 10.8–16.9 | 7.4–10.3 |

| e. Graduate or professional degree (%) | (II) 5 | 1.9–4.4 | 1.2–2.0 |

| f. Bachelor’s degree or higher (%) | (II) 5 | 12.7–21.2 | 8.6–12.2 |

NOTES: FCC: Family Child Care. CPS and ACS data in this table come from occupational and industry codes. Groups are not subsets of each other.

SOURCES: Unpublished tabulations of data fromtthe CPS (2010) and the ACS (2009). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2011.

TABLE B-10B Educational Attainment, 2009–2010

| Type and N Studies | Preschool Teachers | |

| a. High school diploma or equivalent (%) | (III) 5, (V) 2 | 2.0–22.0 |

| b. Some college (%) | (III) 5, (V) 2 | 13.0–32.5 |

| c. Associate’s degree (%) | (III) 5, (V) 2 | 12.0–18.0 |

| d. Bachelor’s degree (%) | (V) 2 | 18.1–49.0 |

| e. Graduate or professional degree (%) | (V) 2 | 24.0–25.6 |

| f. Bachelor’s degree or higher (%) | (III) 5, (V) 2 | 28.1–73.2 |

SOURCE: Data from (III) studies come from the Head Start FACES. Data from (V) study come from the MSSPK and the SWEEP.

Educational Attainment

Preschool teachers had the highest levels of educational attainment: 18 to 49 percent obtained a bachelor’s degree, and 24 to 26 percent obtained a graduate or professional degree. However, preschool teachers in these studies come from samples based on state-sponsored programs, so it is likely that they have higher education levels than other prekindergarten teachers. Education levels were lower for child care workers and FCC providers. Approximately a third of each of these groups did not attend college past high school. However, 11 to 18 percent of child care workers

TABLE B-11 ECCE-Specific Education

| Type and N Studies | Preschool Teachers | |

| Obtained associate’s degree in ECE (%) | (V)1 | 12 (2001) |

| Obtained bachelor’s degree in ECE (%) | (III) 1, (V) 1 | 31 (2001) |

| Obtained advanced degree in ECE (%) | (IV) 1, (V) 1 | 13 (2001) |

| Obtained CDA (%) | (I) 1, (III) 7 | 22.8 (2004)-76.1 (1997) |

| Obtained a state awarded certificate (%) | (III) 2 | 29.3 (2004)-57.2 (2006) |

| Obtained a teaching certificate/license (%) | (III) 3 | 34 (2000)-38.6 (2006) |

NOTE: CDA: Child Development Associate.

SOURCE: Data from (III) studies come from the Head Start FACES. Data from (V) study come from the MMSSPK and the SWEEP.

and 7 to 10 percent of FCC providers completed college with a bachelor’s degree.

ECE-Specific Education

Caregivers and teachers vary in the amount of ECE-specific education that they obtained, as shown in Table B-11. As of 2001, 12 percent of preschool teachers had obtained an associate’s degree in ECE, 31 percent obtained a bachelor’s in ECE, and 13 percent obtained an advanced degree in ECE. The percentage of prekindergarten teachers who obtained a child development associate (CDA) credential, state-awarded certificate, or other type of teaching certificate varied across studies. For example, 23 percent of teachers in the 2004 National Prekindergarten Study had obtained a CDA, but 76 percent of teachers in the 1997 Head Start Family and Child Experiences Survey reported obtaining one.

Professional Development

Several studies also recorded whether teachers engaged in other types of professional development. Teachers in the National Prekindergarten Study spent an average of 33 hours in training within the past year, while 39 to 47 percent of teachers in the different waves of the Head Start Family and Child Experiences Survey were currently enrolled in teacher-related training at the time of the survey. These data are presented in Table B-12.

TABLE B-12 Professional Development

| Type and N Studies | Preschool Teachers | |

| Mean hours in training in past 12 months (hours) | (III) 1 | 32.9 (2004) |

| Currently enrolled in teacher-related training (%) | (III) 3 | 38.7 (2006)–46.5 (2001) |

SOURCE: 2004 data come from the NPS. 2001 and 2006 data come from the Head Start FACES.

TABLE B-13 Mean Years in Caregiving Field

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool Teachers |

| (I) 1, (III) 3, (V) 4 | 4.0–5.4 (1994) | 6.8 (1997)–11.8 (2000) |

SOURCES: 1994 data come from the NICHD SECCYD. 1997 data come from the NCEDL-S. 2000 data come from the Head Start FACES.

ECCE Experience

Across studies, child care workers reported having an average of 4 to 5 years of work experience in the ECCE field, while preschool teachers had an average of 7 to 12 years of experience. Head Start teachers had spent an average of 8 to 9 years teaching in Head Start classrooms.

Note that these data, shown in Table B-13, are estimates of current level of experience, not of the duration of time workers will remain in the field. They reflect questions asked of active workers, rather than of workers who had retired or left the field. The respondents would thus continue to work in the field for an underdetermined amount of time. Duration or tenure will thus exceed current years of experience, but we do not currently have data reflecting duration.

Labor Market Characteristics: Compensation (Wages, Benefits), Full-/Part-Time Employment, Hours Worked per Week, Other Employment, and Job and Occupational Turnover

Compensation

In this section we address two components of compensation: earnings and benefits (health and retirement).

Earnings The Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Current Population Survey provide median weekly earnings estimates for workers by occu-

TABLE B-14 Median Weekly Earnings (Dollars)

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers | FCC Providers |

| (II) 2 | 400.00 (2010) | 621.00 (2010) | 269.23 (2010) |

NOTE: FCC: Family Child Care. Data in this table reflect standard occupational and industry codes. Groups are not subsets of each other.

SOURCE: Child Care Worker and Preschool/Kindergarten Teacher data from the BLS (ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/lf/aat39.txt). FCC studies based on unpublished tabulations of data from the CPS (2010), U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2011.

pation and industry, which we include as our primary compensation estimates. As seen in Table B-14, child care workers earned an average of $400 per week in 2010, preschool and kindergarten teachers averaged $621 per week, and FCC providers earned the least—$269 per week.

As a point of comparison, for full-time, year-round workers, these median annual earnings would be approximately $20,800 for child care workers, $32,292 for teachers, and $14,000 for FCC providers if we were to multiply these estimates by 52 weeks in a year. By contrast, the median weekly wage across occupations in 2010 was $747 (or $38,844 annually).7 However, many ECCE staff are not employed full-time and do not work at their jobs for 12 months a year. As shown in Table B-15, less than half of FCC providers work full-time, and at most two-thirds of child care workers are employed full-time. Because of the lack of full-time employment for ECCE workers, the yearly earnings estimates will be lower than those provided for full-time, year-round workers.

Many child care workers are also employed in school-based or school-related programs, which only operate about 9 months of the year. Enrollment at community-based child care centers drops substantially in the summer as parents take vacations and move houses; some staff takes vacation, others are temporarily not employed. However, even though they are not working at their normal ECCE jobs, such staff may be employed in other occupations or locations. Some teachers are employed in summer sessions. Others may use the time to gain college credits, which can increase their earnings. Therefore, the net financial impact of compensation for individual workers for varying employment throughout the year is not fully captured by any standard data source that we are aware of.

![]()

7 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010, “Table 39: Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by detailed occupation and sex,” Household Data Annual Averages, ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/lf/aat39.txt.

TABLE B-15 Percentage Who Work Full Time, 2009–2010

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers | FCC Providers |

| (II) 4 | 51.0–64.7 | 71.3–74.2 | 37.8–42.6 |

NOTE: FCC: Family Child Care. Data in this table reflect standard federal occupational and industry codes. Groups are not subsets of each other.

SOURCE: Unpublished tabulations of data from the CPS (2010) and the ACS (2009). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2011; HSPC demand-based estimates. Brandon et al. (2011).

Weekly Hours and Full-Time/Part-Time Status

As shown in Table B-15, a large majority of the ECCE workforce, with the exception of FCC providers, worked full-time and many worked more than 40 hours per week. Preschool and kindergarten teachers as a group had the largest percentage of full-time workers (71–74 percent), child care workers (51–65 percent), and finally FCC providers (38–43 percent). These rates of full-time employment are all lower than the average for the total population of employed persons age 16 and older, which was approximately 80.3 percent in 2010.8

According to 2003–2007 data from the ATUS, child care workers reported working 34 hours per week on average; however in the BLS current employment series, employers report an average of 30.3 hours/week for child care workers. Teachers in the National Prekindergarten Study reported 37 hours per week of work. Teachers also reported spending an average of 4 hours per week in planning time for classes. About half of prekindergarten teachers (54 percent) performed 2 to 4 hours per week of unpaid planning time as well.

Benefits A major economic consideration for ECCE workforce is access to retirement and health benefits. In this section we summarize previously unpublished data from the 2010 National Compensation Survey provided specifically for this study.9 As for other BLS data, we note that Child Care Workers and Child Day Care Services includes school-aged as well as ECCE workers. It should also be noted that the data do not distinguish between full- and part-time workers. Because part-time workers often

![]()

8 Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010, “Table 8: Employed and unemployed full- and part-time workers by age, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity,” Household Data Annual Averages, ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/lf/aat8.txt.

9 U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Health and Retirement Benefit Access and Participation; Employer Costs for Employee Compensation, March 2010. Breakdown by selected occupations and industries. Personal communication with Philip M. Doyle, assistant commissioner, May 10, 2011.

receive fewer benefits, and the share of part-time workers is higher for ECCE than for the total population of civilian workers; the comparison between ECCE and total workers may be slightly overstated.

Tables B-16A through B-16F summarize employer-reported benefits for the two major components of the ECCE workforce regularly tracked by BLS: child care workers and preschool teachers. These are divided by the category of the establishment where they work: child day care services (column 2) versus elementary and secondary schools (column 3). Other workers in these establishments, such as directors or food service workers, are reflected in the first row—all workers—under the establishment category. Child care workers and preschool teachers in other types of establishments—e.g., health facilities—are reflected in rows 2–4 of the first column. For sake of comparison, the entry in the first row and first column shows the value for all civilian workers in all industries. It should be noted that the total includes the ECCE workers, but because they represent less than 1 percent (about 0.006) of the total workforce the error in the comparison is slight.

Health Benefits Table B-16A shows the share of child care and preschool workers with access to employer health benefits. Access for ECCE is slightly more than half the rate for all civilian employees: 38 versus 74 percent. Preschool teachers slightly exceed the national average, with 75

TABLE B-16A Percentage of Civilian Workers with Access to Employer-Provided Health Insurance

| All Industries | Child Day Care Services | Elementary and Secondary Schools | Child Day Care Services and Elementary and Secondary Schools | |

| All workers (in all occupations) | 74 | 49 | 88 | 84 |

| Child care workers and preschool teachers, except special education | 38 | 31 | 60 | 39 |

| Child care workers | 31 | 26 | 47 | 31 |

| Preschool teachers, except special education | 63 | 64 | 90 | 75 |

SOURCE: BLS National Compensation Survey, 2010.

TABLE B-16B Percentage of Civilian Workers Participating in Employer-Provided Health Insurance

| All Industries | Child Day Care Services | Elementary and Secondary Schools | Child Day Care Services and Elementary and Secondary Schools | |

| All workers (in all occupations) | 60 | 26 | 75 | 70 |

| Child care workers and preschool teachers, except special education | 22 | 12 | 44 | 20 |

| Child care workers | 16 | 9 | 37 | 15 |

| Preschool teachers, except special education | 43 | 29 | 60 | 43 |

SOURCE: BLS National Compensation Survey, 2010.

percent access having access to benefits. However, only 39 percent of child care workers have access.

Access varies greatly between workers in the community-based child day care services industry, for which access is 31 percent, and elementary-secondary schools, which have 60 percent access. Even within the schools, 90 percent of preschool teachers have access to health benefits, compared to 47 percent of child care workers. In child day care services, the rates are lower but the discrepancy just as great: 64 percent of preschool teachers have access versus 26 percent of child care workers.

However, not all employees participate in employer-sponsored plans to which they have access. For some, the contributions or co-payments may be too high. Others may be covered under their spouse or partner’s plan. Table B-16B shows the actual participation.

Thus, while 38 percent of all ECCE employees have access to health benefits, only 58 percent of those actually participate. For child care workers, the take-up rate is only 53 percent yielding 16 percent with employer coverage, while for preschool teachers it is 68 percent, yielding 43 percent participation.

Just as there are discrepancies in the percentage of workers having access to and participating in health benefits, there appear to be discrepancies in the amount contributed by employers to those benefits. It should be noted that the average cost includes hours worked by part-time

TABLE B-16C Average Hourly Cost to Employers per Worker Participating in Employer-Provided Health Insurance: Author’s Estimates

| All Industries | Child Day Care Services | Elementary and Secondary Schools | Child Day Care Services and Elementary and Secondary Schools | |

| All workers (in all occupations) | 3.06 | 1.30 | 5.62 | 5.30 |

| Child care workers and preschool teachers, except special education | 2.05 | 0.95 | 4.48 | 2.26 |

| Child care workers | 1.83 | 0.67 | 4.15 | 1.95 |

| Preschool teachers, except special education | 2.90 | 2.38 | 5.09 | 3.71 |

SOURCE: BLS National Compensation Survey, 2010.

employees who are likely to have fewer benefits. However, to the extent that ECCE employs a higher share of part-time employees than the overall civilian economy reflects part of the structural difference in employment and compensation.

Table B-16C shows that average hourly employer costs for ECCE are about one-third lower than for the average workers—$2.05 versus $3.06 per hour. The distribution within ECCE parallels that for access and participation. Employer costs for preschool teachers schools are close to the overall average—$2.90 versus $3.06. For those in elementary and secondary schools, the costs are close to that for all school employees—$5.09 versus $5.62 per hour.

Retirement Benefits Tables B-16D, B-16E, and B-16F show similar information regarding employer-based retirement benefits. While 69 percent of employees in all industries have access to retirement benefits, only 30 percent of child care workers and 47 percent of preschool teachers have such access. As with health benefits, access is much higher for workers in schools than in other facilities.

Of the 69 percent of all workers with access to retirement benefits, 55 percent participate. For child care workers, 18 percent out of the 30 percent with access participate, and for preschool teachers all of the 47 percent with access participate. Combining all ECCE workers—child care

TABLE B-16D Percentage of Civilian Workers with Access to Employer-Provided Retirement Benefits

| All Industries | Child Day Care Services | Elementary and Secondary Schools | Child Day Care Services and Elementary and Secondary Schools | |

| All workers (in all occupations) | 69 | 30 | 90 | 84 |

| Child care workers and preschool teachers, except special education | 34 | 18 | 67 | 31 |

| Child care workers | 30 | — | 64 | 27 |

| Preschool teachers, except special education | 47 | — | 74 | 49 |

NOTE: Dashes indicate no workers in this category or data did not meet publication criteria.

SOURCE: BLS National Compensation Survey, 2010.

TABLE B-16E Percentage of Civilian Workers Participating in Employer-Provided Retirement Plans

| All Industries | Child Day Care Services | Elementary and Secondary Schools | Child Day Care Services and Elementary and Secondary Schools | |

| All workers (in all occupations) | 55 | 21 | 87 | 80 |

| Child care workers and preschool teachers, except special education | 24 | 9 | 59 | 23 |

| Child care workers | 18 | — | 54 | 17 |

| Preschool teachers, except special education | 47 | — | 72 | 48 |

NOTE: Dashes indicate no workers in this category or data did not meet publication criteria.

SOURCE: BLS National Compensation Survey, 2010.

TABLE B-16F Average Hourly Cost to Employers per Worker Participating in Employer-Provided Retirement Benefits: Author’s Estimates

| All Industries | Child Day Care Services | Elementary and Secondary Schools | Child Day Care Services and Elementary and Secondary Schools | |

| All workers (in all occupations) | 1.65 | 0.27 | 3.32 | 3.05 |

| Child care workers and preschool teachers, except special education | 0.75 | 0.13 | 1.85 | 0.70 |

| Child care workers | 0.48 | — | 1.45 | 0.49 |

| Preschool teachers, except special education | 1.41 | — | 2.69 | 1.42 |

NOTE: Dashes indicate that no workers in this category or data did not meet publication criteria.

SOURCE: BLS National Compensation Survey, 2010.

and preschool, community-based and schools—23 percent actually participate in retirement benefits out of the 31 percent who have access.

Table B-16F shows the average hourly employer contribution to employee retirement plans. The pattern is similar to that for health insurance. Child care workers have average benefits that are less than a third of the average worker—$0.48 versus $1.65—while preschool teachers’ benefits are slightly lower. Benefits in schools are more generous than in community-based settings. Average retirement costs for all workers in schools are nearly double that for the average U.S. worker—$3.32 versus $1.65. Preschool teachers in schools receive about 20 percent lower retirement benefits—$2.69 per hour worked—which is still much higher than preschool teachers in non-school settings.

Other Employment

According to CPS data, a small percentage of child care workers (5 percent) also worked additional jobs outside of their main employment. Four percent of teachers and 3 percent of FCC providers had an additional job. Of those with additional employment, child care workers spent about

16 hours per week at an extra job and teachers spent about 15, according to the 1993 CQCO study. These data are presented in Table B-17.

Job and Occupational Turnover

Turnover is a concern for many researchers and policy makers in the child care field. It is important to distinguish between job turnover—changing jobs within the ECCE field—and occupational turnover—leaving ECCE for another field. National studies have generally showed annual job turnover rates to be about one-third of child care workers and 19 to 39 percent of teachers. Data from California, gathered as part of the 1994–2000 study, Then and Now: Changes in Childcare Staffing, indicate that job turnover between 1999 and 2000 for all teaching staff was about 32 percent and occupational turnover was about 16 percent. Teachers and staff in this study also experienced a 2 to 6 percent decrease in wages in this time period. Data on annual job turnover are presented in Table B-18.

Professional Attitudes and Orientation: Union and Professional Organization Membership

Various aspects of professionalism have been demonstrated to predict the observed quality of caregiving and child outcomes. We do not have reliable national data on attitudes and orientation. However, there are

TABLE B-17 Percentage of Workers With Additional Job, 2010

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers | FCC Providers |

| (II) 2 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 3.3 |

NOTE: FCC: Family Child Care. Data in this table reflect standard federal occupational and industry codes. Groups are not subsets of each other.

SOURCE: Unpublished tabulations of data from the CPS (2010) and the ACS (2009). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2011.

TABLE B-18 Annual Job Turnover (%)

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Center-Based Teachers |

| (I) 1, (IV) 1 | 33–36.4 (1993) | 19 (1990)–38.7 (1993) |

SOURCE: Data from 1990 come from the PCCS study. Data from 1993 come from the CQCO study.

data regarding the aspects of professionalism involved in deciding to join a union or professional association.

As expected, union participation was highest among preschool teachers. Twenty-one percent of teachers indicated that they were union members (Table B-19). Rates of union membership were lower for child care workers (4–6 percent) and lowest for FCC providers (<1 percent).

Additionally, 53 to 62 percent of teachers and 14 percent of total child care workers indicated that they were members of one or more professional associations (Table B-20).

TABLE B-19 Percentage of Workers Unionized, 2010

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers |

FCC Providers |

| (II) 2 | 3.5–6.3 | 20.8 | 0.80 |

NOTE: FCC: Family Child Care. Data in this table reflect standard federal occupational and industry codes. Groups are not subsets of each other.

SOURCE: Unpublished tabulations of data from the CPS (2010) and the ACS (2009). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2011.

TABLE B-20 Percentage of Members of Professional Organization

| Type and N Studies | Child Care Workers | Preschool Teachers |

| (III) 3, (IV) 1 | 14 (1988) | 52.9 (1997)–62 (2000) |

NOTE: Groups are not subsets of each other.

SOURCE: 1988 data come from the NCCSS. 1997 and 2000 data come from the Head Start FACES.

STUDY LIST

I. Nationally representative; cover all children age B–5 (birth–age 5) and distinguish B–5 from school age; include most settings (2)

-

Profile of Child Care Settings (PCCS), 1990

-

National Households Education Survey (NHES); Human Services Policy Center (HSPC)/Center for the Child Care Workforce (CCW) Child Care Workforce Estimates Study, 2005

II. Nationally representative; include most settings; cover all B–5 but do not distinguish from school-age (7)

-

Current Population Survey (CPS), 2004

-

CPS; Occupation, 2010

-

CPS; Industry, 2010

-

American Community Survey (ACS); Occupation, 2009

-

ACS; Industry, 2009

-

Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), 2009

-

American Time Use Survey (ATUS); HSPC Estimating the Economic Value of Early Care and Education, 2005–2007

III. Nationally representative; cover a portion of B–5 workforce or settings; e.g., prekindergarten, Head Start (7)

-

Head Start Impact Study (HSIS), 2002–2006

-

Head Start: The Family and Child Experiences Survey (FACES), 2006–2007

-

Head Start: FACES, 2001

-

Head Start: FACES, 2000

-

Head Start: FACES, 1997

-

National Prekindergarten Study (NPS), 2003–2004

-

National Center for Early Development and Learning Survey (NCEDL-S), 1997

IV. Multistate; cover all of B–5 workforce by child age and setting (4)

-

National Child Care Staffing Study (NCCSS), 1988

-

Cost, Quality and Child Outcomes in Child Care Centers (CQCO), 1993

-

National Day Care Study (NDCS), 1976–1977

-

National Day Care Home Study (NDCHS), 1980

V. Multistate; cover portion of B–5 workforce and settings; e.g., prekindergarten (5)

-

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), 15 Months

-

NICHD SECCYD, 24 Months

-

NICHD SECCYD, 36 Months

-

Multi-State Study of Pre-Kindergarten (MSSPK), 2001

-

Statewide Early Education Programs Survey (SWEEP), 2001–2003

VI. Single state: cover all B–5 workforce (21)

-

AZ: Survey of Arizona’s Early Education Workforce, 2004

-

CA: California Early Care and Education Workforce Study—Family Child Care Survey, 2005

-

CA: California Early Care and Education Workforce Study—Center Survey, 2005

-

FL: Child Care Workforce Study, 2006

-

IL: Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS) Illinois Salary and Staffing Survey of Licensed Child Care Facilities, 2008

-

IN: Survey of Teachers and Directors Working in Licensed Child Care Centers and Unlicensed Child Care Ministries, 2007

-

ME: Maine Child Care Market Rate and Workforce Study, 2002

-

MN: Child Care Workforce in Minnesota, 2006–2007

-

MN: Child Care Workforce in Minnesota, 2006–2007

-

MN: Child Care Workforce in Minnesota, 2006–2007

-

NYC: New York City Early Childhood Educators Survey, 2006

-

NC: North Carolina Child Care Workforce Survey, 2003

-

OH: Workforce Study of Ohio Early Childhood Centers, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services (ODJFS), 2005

-

OH: Workforce Study of Ohio Early Childhood Centers, Ohio Department of Education (ODE), 2005

-

PA: Early Care and Education Provider Survey, 2002

-

UT: Study of Childcare Workforce in Utah, 2006

-

VA: Childcare Workforce Study in Metro Richmond, Virginia, 2003

-

WI: Statewide Child Care Surveys, 1980

-

WI: Statewide Child Care Surveys, 1988

-

WI: Statewide Child Care Surveys, 1994

-

WI: Statewide Child Care Surveys, 2001

VII. Single state: cover portion of B–5 workforce and settings; e.g., prekindergarten (4)

-

CA: Changes in Child Care Staffing Study, 2000

-

MA: Cost Quality (CQ) Center Study, 2000-2001

-

MA: CQ Public School Study, 2000-2001

-

MA: CQ FCCH Study, 2000-2001

DESCRIPTION

I. Nationally Representative Studies; Cover All Children Age B–5 (Birth–Age 5) and Distinguish B–5 from School Age; Include Most Settings

National Household Education Survey, Early Childhood Supplement (NHES); Human Services Policy Center (HSPC)/Center for the Child Care Workforce (CCW) Child Care Workforce Estimates Study

-

Study Dates: 1999, 2005

-

Agency: HSPC; CCW

-

Demand-based estimation of the early child care and education workforce

-

Uses 1999 and 2005 data from the NHES to calculate estimates of child care workforce

-

NHES is a large-scale, nationally representative survey that asks respondents questions about the hours spent in a variety of care arrangements in a typical week.

-

The NHES is a random-digit-dial telephone survey of the general population, with 7,198 household respondents with children age B–5.

-

Limitations:

ο Study itself does not sample ECCE workers.

Sources

Brandon, R. N., T. J. Stutman, and M. Maroto. 2011. The economic value of early care and education in the U.S. In Economic Analysis: The Early Childhood Sector, ed. E. Weiss and R. Brandon. Washington, DC: Partnership for America’s Economic Success.

Center for the Child Care Workforce and Human Services Policy Center. 2002. Estimating the size and components of the U.S. child care workforce and caregiving population: Key findings from the child care workforce estimate, executive summary: Preliminary report. Washington, DC: Center for the Child Care Workforce.

Profile of Child Care Settings (PCCS)

-

Study Date: 1990

-

Agency: Mathematica Policy Research Group

-

This study’s goal was to focus on the availability (supply side) of early education care.

-

The study is a nationally representative sample drawn from the universe of formal early education care programs.

-

Computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) survey with nationally representative sample of center directors and regulated home-based child care providers that are licensed or registered by the state or county in which they are located.

-

Uses a two-stage clustered sample design: (1) 100 representative counties stratified according to region, metro status, and poverty level and (2) centers within counties.

-

Sample N: 2,089 centers and 583 regulated home-based child care providers

-

Provide weighted estimates in report

-

Limitations:

ο Year/age of study

Source

Kisker, E. E., S. L. Hofferth, D. A. Phillips, and E. Farquhar. 1991. A profile of child care settings: Early education and care in 1990. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; Washington, DC: Department of Education.

II. Nationally Representative; Most Settings; Cover All B–5 But Do Not Distinguish from School-Age

American Community Survey (ACS)

-

Data Date: 2009 single-year estimates

-

Agency: U.S. Census Bureau