Lessons from Abroad—

Clusters, Parks, & Poles in

Global Innovation Strategies

Moderator:

Stephen Lehrman

Office of U.S. Senator Mark Pryor (D-AR)

Mr. Lehrman expressed the appreciation of Senator Pryor to the National Academies, Dr. Mary Good, and Dr. Charles Wessner for leading the effort to look at innovation, research parks, and innovation clusters. Mr. Lehrman noted this panel built on work Dr. Good and Dr. Wessner did in 2009 that led to the book Understanding Science and Technology Parks.39

Senator Pryor also is very thankful, he said, to the Association of University Research Parks, National Academies members, and Senator Olympia Snowe (R-ME), his partner in legislation to stimulate funding for research parks, technopoles, and science parks in the United States.40 He added that the Senator is hopeful it will pass this year.

Many nations view science and research parks as “catalysts of the development of innovation and innovative clusters that support rapid economic growth and attract a talented and education workforce,” Mr. Lehrman said. “The rest of the world has caught up with the United States over the last 40 years, and in many cases has surpassed us in the way they are developing their research and science parks,” he said. “Now it is up to us to learn from their lessons in how to modernize our systems here in the United States.”

Many of these nations are making substantial investments in parks and

![]()

39 National Research Council, Understanding Research, Science and Technology Parks: Global Best Practices—Report of a Symposium, op. cit.

40 The Building a Stronger America Act was passed by the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee on December 17, 2009. It allows the “Secretary of Commerce to guarantee up to 80 percent of loans exceeding $10 million for construction of science parks and would provide grants for feasibility studies and construction plans for new parks or expansions.” The National Academy of Sciences is mandated to evaluate the program.

clusters that create regional and national centers of economic development and that facilitate new technology, Mr. Lehrman observed. “Eventually, that is the goal of all of us,” he said, “which is economic development, the development of new products, and commercialization of technology.”

Mr. Lehrman said the panel is fortunate to have four experts on clusters, science parks, and technopoles, and how they contribute to the innovation systems of their nations and regions.

AN INTEGRATED APPROACH:

BRAZIL’S MINAS GERAIS STRATEGY

State Secretary Duque Portugal began with a few facts about Minas Gerais. The state is located west of Rio de Janeiro, Brasilia, and Sao Paulo, has a population of 20 million, and covers a territory about the size of France.

The state’s economy has been growing “reasonably well,” Dr. Portugal said. It has a GDP of $122 billion and the nation’s second-largest industrial park. The state is a leader in mining, metallurgy, coffee, biotechnology, and other industries. For Brazil, Minas Gerais has roads, railways, airports, and other infrastructure, and is responsible for 18.5 percent of the nation’s energy generation.

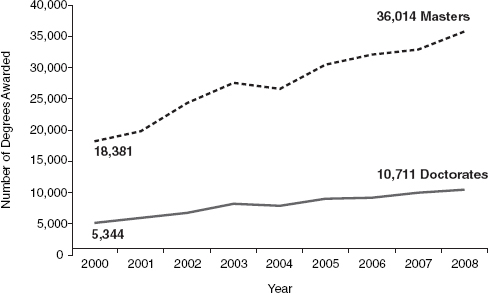

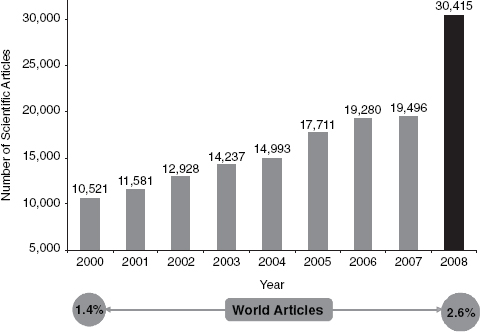

By many measures, Brazil has been making good strides in terms of scientific output, he noted. The number of Brazilian articles published in scientific journals has grown from less than 5,000 a year in the early 1990s to more than 30,000 in 2008, and its global share of such papers has risen from about 0.5 percent to 2.6 percent. Master’s degrees awarded annually have surged from around 5,000 in 1993 to 33,360 in 2008. Ph.D degrees have risen sharply, to 10,711. That is a good output for a Latin American country and emerging nations, he said.

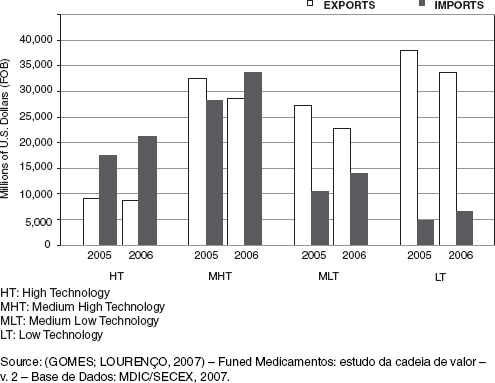

The big challenge “is how to transfer this science and technology into production, productivity, quality, competitiveness, and better employment,” Dr. Portugal said. He displayed a slide that shows the “technology intensity” of foreign trade in Brazil. In 2006, Brazil imported more than twice as many “high-technology” goods, valued at around $21 billion, than it exported. Brazil also imported more “medium high-technology” goods than it exported that year. The country enjoys a large surplus in “medium-low technology” and “low technology” products. He noted that these data are a bit out of date. While there is improvement, however, the balance isn’t substantially different.

Brazil exports a lot of agricultural goods and raw materials, such as iron and soybeans, which require technology. Such products, however, don’t have a lot of aggregate value, he said. “So the big challenge we have is how to provide more value to the economy through innovation.”

FIGURE 9 Technology intensity in foreign trade in Brazil.

SOURCE: Alberto Duque Portugal, Presentation at February 25, 2010, National Academies Symposium on “Clustering for 21st Century Prosperity.”

Minas Gerais has a substantial research base, Dr. Portugal said. It has federal universities and four state universities with 91,322 students. Universities in the state awarded 2,850 master’s degrees and 904 doctorates in 2008. The state also has 283 private institutions conducting more than 8,500 research projects and employing 15,842 researchers. Universities spend $1.3 billion annually on R&D.

The state has invested more than $300 million in the past four years to build its innovation system, Dr. Portugal said. Its science and technology education master plan has four main goals:

• To transform knowledge into business to raise productivity and competitiveness, contributing to economic development.

• To make Minas Gerais a leader in the knowledge economy.

• To consolidate in society the perception that science, technology, and innovation are strategic areas.

• To align the actions and indictors of the science, technology, and higher-education systems.

To advance this agenda, Dr. Portugal said, the state created Sistema Mineiro De Inovação, better known as SIMI. This organization is an operational platform to promote innovation. It has a forum chaired by the governor, a higher-education observatory, and a Web 2.0 Internet portal enabling researchers, entrepreneurs, and others to talk to each other. SIMI also has a “technological innovation network” that provides skills training, an outreach program to transfer technology to businesses across the state, a committee of entrepreneurs to support and stimulate innovation, and international partnerships.

All of these activities concentrate on some basic points. They focus on speed, achieving scale “in order to reach as many actors as possible” with finite resources, and improving “social technology,” Dr. Portugal said. An overarching goal is to “improve collaboration, coordination, and strategic alliances to create an environment and stimulate an attitude for a culture for innovation.”

To build an “innovation environment,” SIMI is promoting technology parks, incubators, R&D centers, and a program called Innovate in Minas. SIMI also is hosting a technology fair in October.

There are a variety of programs designed to bring technology to business. They include an innovation incentive program for businesses, technology innovation units, programs to promote basic industrial technology, a design center, and assistance in coordinating venture capital. To promote “innovation in society,” Dr. Portugal explained, SIMI supports several entrepreneurship training programs, including master’s level courses. It also supports a network of 1,800 centers that work with higher education to train professionals needed by emerging clusters. For example, there is a program to meet projected workforce needs in aerospace, a rising industry in Brazil.

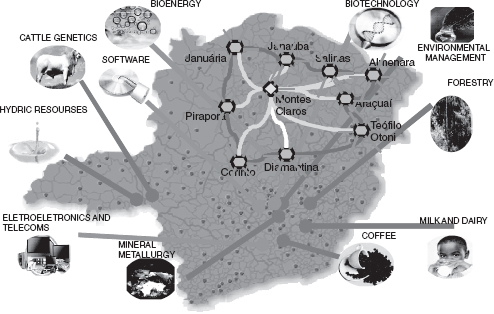

SIMI is aligning these programs to advance the development of four regional clusters that Minas Gerais has targeted because they have the potential to make a high economic impact. A micro-electronics and telecom cluster is based in the southwest of the state. Growing software and biotechnology clusters are concentrated in central Minas Gerais. A bio-energy cluster, which includes charcoal, bio-fuels, and solar power, is expanding in the north. Among other things, SIMI is developing programs to support entrepreneurs, train management, and promote exports in these industries.

In addition to innovation clusters, the state is working to develop what it calls “poles of excellence.” These are establishing industries in which communities in Minas Gerais already have expertise and leadership. They include metallurgy, telecommunications, cattle genetics, forestry, dairy, environmental management, and coffee. The state government is trying to develop certain cities into national hubs for these industries. It is encouraging private companies and public agencies to consolidate their people, laboratories, and management in these hubs. The goal, Dr. Portugal explained, is to enable the hubs to attain critical mass and become magnets for new investment and R&D.

One problem is that most of the clusters and poles of excellence are located

FIGURE 10 Poles and clusters of Minas Gerais.

SOURCE: Alberto Duque Portugal, Presentation at February 25, 2010, National Academies Symposium on “Clustering for 21st Century Prosperity.”

in the southern half of Minas Gerais. The north is poorer and less densely populated. The government is investing a lot in roads, education, health, and other infrastructure in the north to spread development, Dr. Portugal said.

Meanwhile, SIMI is developing what Dr. Portugal described as a “network of pools of innovation,” or linkages between cities across the nation to create channels to disseminate best practices. To make such an innovation platform work, he added, “we also have to invest in human resources.” SIMI began working with two towns that have universities to create a pool of highly skilled people, including Ph.Ds.

SIMI also is forging international partnerships to advance its innovation strategy. Currently, it is working with Italy’s Piedmont region in energy, mobility, and automotive technology; the German state of Saarland in nanotechnology; the Australian state of Queensland in mining, water, and sustainable management, and France’s Brittany region in dairy and Web. 2.0 technologies. SIMI is working to internationalize its organization.

Dr. Portugal invited the audience to attend the 2010 INOVATEC fair, which stands for Technology and Innovation Fair and Congress. INOVATEC is an opportunity for researchers, private industry, government agencies, and R&D centers to interact and exchange ideas, he said. In 2008, INOVATEC’s main partner

was Italy. In 2009, the focus was on France. In 2010, the invited country is the United States. Among the priorities are to foster cooperation in solar energy. The state hopes to attract participants from U.S. government agencies, R&D, institutes, and companies.

BRAZIL’S NEW INNOVATION STRATEGY

Francelino Grando

Ministry of Development, Industry, and Foreign Trade, Brazil

Dr. Grando, Brazil’s Secretary of Innovation, said he could sum up his goal in a single word: “system.” He added a second word: “articulation.” By this, Dr. Grando said, “I mean that within a government, a federal government, we see that different parties of the same body do not speak in the same language, do not address each other, and do not even know what the others are talking about. So we see system and articulation within the government as the keys to what we call Brazil’s new innovation strategy.”

Articulation is needed at the federal, state, and local levels, he said. But it is possible to speak the same language. He noted that within Brazil’s Ministry of Science and Technology, a number of top officials have been local secretaries of science and technology. “So, of course, we bring to national government the same purpose,” he said. He also noted that the national forum of local secretaries of science and technology is represented on the national board of science and technology, which advises the President.

As a university professor, Dr. Grando said he agrees with Dr. Daniel of the University of Texas at Dallas on the central role of universities. This has been Brazil’s focus for more than a half century with public federal and state money, he said.

Brazil has made particularly impressive progress in the first decade of the 21st century toward increasing its knowledge base. Between 2000 and 2008, he noted, the number of master’s degrees awarded annually has doubled, to 36,014, and the number of doctorates also has doubled, to 10,711. “This is a huge output, and this is the result of permanent, dedicated investment for decades and through several different governments,” he said.

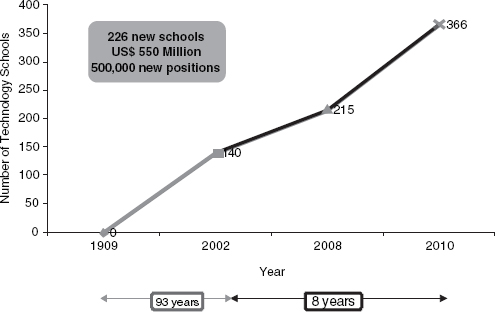

Recently, Brazil has put greater emphasis on science and technology education, Dr. Grando said. It took more than 100 years to establish 140 technology schools. From 2002 to 2010 alone, that number has swelled to 366. Government investment of $550 million in these schools has created 500,000 new student positions. This intermediate level of training, he said, “creates a strong base for knowledge production.” These schools also are spread across Brazil, even in the Amazon rain forest, which accounts for half of the nation’s territory.

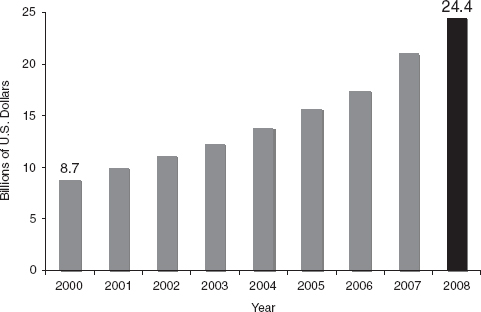

Dr. Grando pointed to other indicators of scientific output. Brazilian scientists have sharply increased published papers. Public and private R&D investment, meanwhile, soared from $8.7 billion in 2000 to $24.4 billion in 2008.

FIGURE 11 Increasing knowledge.

SOURCE: Francelino Grando, Presentation at February 25, 2010, National Academies

Symposium on “Clustering for 21st Century Prosperity.”

FIGURE 12 Technology schools.

SOURCE: Francelino Grando, Presentation at February 25, 2010, National Academies

Symposium on “Clustering for 21st Century Prosperity.”

FIGURE 13 Scientific articles.

SOURCE: Francelino Grando, Presentation at February 25, 2010, National Academies

Symposium on “Clustering for 21st Century Prosperity.”

FIGURE 14 R&D expenditure in Brazil.

SOURCE: Francelino Grando, Presentation at February 25, 2010, National Academies

Symposium on “Clustering for 21st Century Prosperity.”

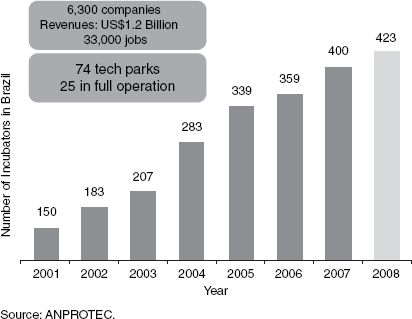

FIGURE 15 Incubators: science + entrepreneurship.

SOURCE: Francelino Grando, Presentation at February 25, 2010, National Academies

Symposium on “Clustering for 21st Century Prosperity.”

Brazil has made equally impressive strides in promoting technology entrepreneurship, Dr. Grando said. The number of small-business incubators in Brazil surged from 150 in 2001 to 423 in 2008. These incubators have helped 6,300 companies. This is the result of policies that help companies “that are getting into the market, not just scattering money on very, very good ideas that are not fit for one reason or another to generate innovative products.”

In addition to the 33,000 jobs created by these new companies, Dr. Grando said, these incubators have been a smart investment. State and national tax dollars generated by these new businesses are three times the amount the government has spent on incubators, he said. “Those are good metrics,” he said.

Infrastructure is important, he said. Even after improving the capacity for knowledge generation and making entrepreneurs more sensitive to innovation, Dr. Grando said, “there still is something that public money has to do.” Brazil set up the equivalent of the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. The agency is called INMETRO, which stands for the National Institute of Metrology, Standardization and Industrial Quality.

INMETRO has sharply increased the number of qualified technicians that are civil servants. The number of master’s degree holders at the agency rose from 27 to 201 since 2000, and the number of doctorates grew from 8 to 152. The number of INMETRO labs has grown from 18 to 53 over that period.

Brazil’s new focus on innovation is present in what Dr. Grando described as two “systemic policies.” One, led by the Minister of Development, is the Productive Development Policy. It entails investment of $150 billion. Of that, $3 billion is devoted to promoting “innovation in a strict sense,” he said. Another $20 billion, managed by the Ministry of Science and Technology, is earmarked for a “science and technology action plan.”

The Ministry of Development is responsible for deciding where to invest the money. Managers in the Ministry of Technology lead teams in specific targeted areas, such as information and communications technology, biotechnology, and nuclear energy. All of these programs “are articulated around a nexus of innovation,” Dr. Grando said.

The ultimate goal of all of these efforts is to attain sustainable growth. “We long for the time when ‘sustainable’ will no longer be an adjective, when development will no longer be qualified as ‘sustainable development,’” he said. “We long for the time when development means only ‘development that is sustainable,’ just as ‘democracy’ does not need a clarification.”

The Secretariat of Innovation, which is part of the Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade and the Secretariat of Innovation, coordinates the national innovation system, Dr. Grando explained. It collaborates with the National Development Bank (BNDES), INMETRO, the National Institute of Intellectual Property (INPI), the Industrial Development Agency (ABDI), and the Export Promotion Agency (APEX). These agencies also communicate with other federal ministries. To help the entire federal bureaucracy to stay in touch, the Secretariat of Innovation is setting up a Web 2.0 portal. “We need innovation in the public administration as well as in the private sector,” Dr. Gordo noted.

Investments in the innovation system have made Brazil more globally competitive, Mr. Grando said. The nation now is self-sufficient in oil production, “a very, very good example of Brazil’s technological development and focus on innovation.” Petrobras is now the world’s fourth-largest energy firm. Brazil also is a leader in production of sustainable energy, he added. “We won’t talk about ethanol here,” he said jokingly, referring to the trade dispute with the United States, which has curbed imports of Brazilian ethanol made from sugar. Brazil also is home to Embraer, the world’s third-largest aircraft manufacturer. Brazil is the world’s fifth-largest personal computer market and is ranked as the fifth-best location for the offshore outsourcing of information technology. Brazilian banks are leaders in Internet bank. There are 175 million users of mobile phones. And 44 out of 50 global major companies operate in the country.

The progress so far “is just the beginning,” Dr. Grando predicted. Given all of the investment, creativity, and systemically articulated programs at all levels of the private and public sectors in Brazil, “there are some quite fascinating experiences ahead of us.”

HONG KONG SCIENCE PARK—OPTIMISING SYNERGIES

Nicholas Brooke

Hong Kong Science and Technology Parks Corporation

Hong Kong has been a “great fan and big believer” in clustering for some time, noted Mr. Brooke, chairman of the corporation that operates the Hong Kong Science Park.

The decision to launch the science park in 2001 was heavily influenced by Hong Kong’s experience in the Asia financial crisis of 1997. The territory’s economy experienced 54 months of deflation, “a pain we are not used to,” Mr. Brooke said. While the crisis was painful, it forced the Special Administrative Region’s leadership to focus on the structure of its economy.

The government realized Hong Kong had to broaden its base beyond industries such as financial services, tourism, and trade, Mr. Brooke said. It concluded that Hong Kong should serve “as a platform for innovation and technology, capitalizing in particular on our location close to the mainland of China,” he said. The park is located 20 minutes from the mainland border, 20 minutes from Hong Kong’s Central district, and 40 minutes from Hong Kong’s airport.

The park was established with public funds, “but it is no holiday,” Mr. Brooke said. “The park basically must operate according to commercial principles.” The Hong Kong Science and Technology Parks Corporation is responsible for operating the park. Even though the Hong Kong government provided all of the money and is the sole shareholder, only 1 of the 16 board members is a government official. Rather, membership comes from a range of industries and from academia.

The government’s role in the park is interesting, Mr. Brooke explained. The government decided it should provide the infrastructure, or the platform for innovation and technology. It has invested $1.5 billion in land and funding for “hard and soft infrastructure” for Phases I and II, he said. In mid-February 2010, the Hong Kong Financial Secretary signed off on $500 million for a third phase. Once the government has made that investment, “the corporation is essentially on its own,” he said. The park must support itself financially.

Hong Kong leaders understood the best way to build a knowledge-based economy was to build on what it already had, Mr. Brooke said. The park’s vision is to position the SAR as a regional platform in innovation and technology. Hong Kong’s geographic location gives it unparalleled access to the mainland market.

Facilities include a major design center, small-business incubators, and industrial estates. These enterprise zones are reserved for companies making high-value products using technologies developed in the park. It is assumed companies making low-value products can manufacture in China, Mr. Brooke said.

What differentiates the Hong Kong science park from many of those in China is the “soft infrastructure,” as opposed to only the “hard infrastructure,” he said. While the scale of Chinese parks is impressive, “many, many of them in fact are

real estate plays,” he added. “They brand themselves as technological parks. But often the technology content, if you like, is actually quite minimal.”

The entire thrust of the Hong Kong Science Park, by contrast, is to foster innovation and technology, Mr. Brookes said. It provides support for selected technologies, incubates new businesses, and promotes collaboration among industry, academia, and researchers.

The park now has state-of-the-art facilities in 20 buildings and will eventually extend to 330,000 square meters. The first phase was finished in 2004. The second opened in 2008, and ground will be broken on Phase III in the fall of 2010, Mr. Brooke said.

The park already has 250 companies. They include R&D operations of major multinationals such as Philips and DuPont, as well as many small and mid-sized companies. There are 30 U.S. companies and others from China, Japan, Taiwan, France, the Netherlands, and other nations. All are referred to as “partner companies,” Mr. Brook said. “It is not a landlord-tenant relationship. We deliberately describe them as partnerships.”

The most iconic structure in the park is known as the “golden egg.” It is a large oval, gold-colored auditorium seating 300 people. It is named after Charles K. Kau, the Nobel Prize-winning fiber optics pioneer.41 The “golden egg” serves as the anchor for everything that happens in the park, he said.

The government also leaves it up to the science park corporation to pick which industrial clusters to focus on. “The government of Hong Kong is not inclined to choose or pick winners because governments usually get it quite wrong,” he said. The corporation has identified clusters where it believes Hong Kong has an advantage and that warrant special attention. It selected electronics, green technology, information and communication technology, precision engineering, and biotechnology. The laboratories support technologies specific to those clusters. “We cannot be all things to all people,” he said.

It is not enough to focus on these broad areas, however. “We decided that if we were to create world-class niche technologies, we had to move to subsets,” Mr. Brooke said. The park selected areas where Hong Kong already is strong, such as RFID, smart cards, and design of integrated circuits for mobile devices. He noted that many telecom chips inside Blackberry devices were designed in Hong Kong. Another Hong Kong cluster focuses on light-emitting diodes for lighting.

The Phase III facilities will focus on new clusters. They are thin-film photovoltaic panels, environmental engineering, and energy management for buildings. “Here we see ourselves as aggregators, as integrators, of technologies that already exist around the world,” he said. Companies in Hong Kong can adapt these technologies so that they are applicable to China and other Asian countries.

![]()

41 Charles Kuen Kao, born in Shanghai in 1933, shared the 2009 Nobel Prize for his work on the use of fiber optics in telecommunications. He was vice-chancellor of Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The breakdown of partner companies and start-ups in the park illustrates the early focus on information technology (IT), Mr. Brooke noted. Thirty-nine percent focus on IT and telecom and 29 percent on electronics. Life sciences and green-technology companies account for 8 percent each and precision engineering for 12 percent, but the importance of these sectors is expected to grow.

The park has 130 companies in the incubation phase, or “babies as I call them,” Mr. Brooke said. The park offers accommodation, technical support, business plans, marketing help, and other things start-ups often lack. The park also helps raise funds, facilitates networking, and offers mentoring, he added. “It’s not just about incubation, but about success as well,” Mr. Brooke said. So far, 213 companies have graduated from incubators and moved into the industrial park. Four are publicly listed. Two of those companies were started with three employees, he added.

The park also offers companies access to a wide local talent pool. At any one time, its Web site advertises 1,000 jobs and information on 5,000 people looking for work. Mr. Brooke said that the park helps place 3,000 people every year in the technology area. In terms of funding, the park has raised 584 million Hong Kong dollars (US$75 million) since 2003 in venture and angel financing.

The park has technology-support laboratories for integrated-circuit design and development, reliability, materials analysis, biotechnology, RFID, photovoltaic testing, wireless communication, and solid-state lighting. Companies are charged just for the cost of lab labor, not rent. “They can either use our people if they want or their people, depending on how sensitive they feel things are,” he said. In addition, the park has an intellectual property service center.

Eighty-eight percent of incubates are from Hong Kong. But among partner companies, 42 percent are foreign-based. The companies produced combined revenues of 62 billion Hong Kong dollars ($8 billion) in 2009, he said. Seven thousand people work in the park, 4,000 of them engaged in R&D. When Phase III is completed, Mr. Brooke said, the park expects to have 450 companies and employ 15,000 people.

Phase III will focus on clean energy technologies. The park plans to commission a study to identify three to four green-tech clusters that would “best position Hong Kong and most benefit the mainland,” he explained.

One of the park’s biggest challenges is low R&D investment by Hong Kong companies, Mr. Brooke said, as well as limited venture capital support for start-ups. He noted that Hong Kong spends less than 1 percent of GDP on R&D, well behind other industrial nations and even less than China.

Still, the park has achieved considerable success. The number of R&D personnel in Hong Kong grew nearly five-fold, to 12,700, between 1998 and 2007, he noted.42 Private industry spending on R&D rose nearly four-fold over that same period, to 6.1 billion Hong Kong dollars ($79 million).

![]()

42 Source: Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Many foreign companies perform R&D in Hong Kong and manufacture in nearby Shenzhen, China. Mr. Brooke predicted more companies would adopt this “Hong Kong-Shenzhen business model.”

DuPont Apollo Ltd.43 is a good example of this model. The unit of DuPont will manufacture thin-film solar modules in a new plant in Shenzhen. But R&D and intellectual property will remain in Hong Kong, where the company feels more comfortable, Mr. Brooke said. DuPont is discussing further collaboration with the Nano and Advanced Materials Institution in Hong Kong. Other corporations using the Hong Kong-Shenzhen business model include Philips, Freescale, Xilinx, and Nvidia.

The next step for Hong Kong is to “widen the menu further,” Mr. Brooke said. The park is exploring new clusters in areas where Hong Kong is well-positioned, such as medical services, creative industries, and educational services.

INNOVATION AND CLUSTERS: WHY THEY ARE BACK ON THE OECD POLICY AGENDA

Mario Pezzini

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Mr. Pezzini, who heads OECD activities that promote regional competitiveness, began by saying he must disagree with those who contend that other countries are trying to copy the United States. “The situation is much more complex,” he said. “A lot of things we are discussing here are not at all new.”

Mr. Pezzini recalled that when he was a manager in the regional government of Emilia-Romagna in Italy prior to joining the OECD in 1995, a series of Americans—including then-Arkansas governor Bill Clinton—visited to study the region’s success at producing clusters with many small and midsized companies. The phenomenon of “many firms relating to each other and being competitive did not happen first in Silicon Valley,” Mr. Pezzini said. “It happened in many other places.”

What is interesting in the policy debate is that “we are now dealing with different units of analysis and intervention,” he said. “This is crucial for what we do.” Mr. Pezzini said policymakers need to move beyond merely inventing new subsidies for firms and understand what really makes clusters competitive.

What is really new, he added, is that many countries are looking at sub-national entities differently, whether they are regions, states, counties, or whatever. Many places had regional economic strategies, but they were mainly regarded as mechanisms to redistribute resources to compensate for disparities. Governments gave subsidies to individual firms belonging to certain sectors. The “big actors,”

![]()

43 DuPont Apollo Ltd. is a fully owned subsidiary of DuPont that will make silicon-based thin-film photovoltaic modules on glass.

federal governments, “acted like Robin Hood to take from the rich and give to the poor,” he said. Northern Brazil, southern Italy, Japan, and northern European countries all used this model.

Regional redistribution strategies failed. “In reality, these disparities are still there,” Mr. Pezzini said. “Using these approaches does not help to exploit the potential of regions. Sometimes they exaggerate the disparities between regions.” Giving subsidies to small entrepreneurs in southern Italy, say, “more or less meant reproducing the same machinery that was already there.” If producers lack economies of scale, the capacity to compete will not grow. “A central government that tries to do everything very often tends to produce cathedrals in the desert,” he said, “investments that do not produce multiplicative effects.”

Now there appears to be a paradigm in regional thinking. “That’s the new thing, not the clusters,” Mr. Pezzini said. “Rather than compensating disparity, many governments are trying to get every region to identify their comparative advantages and to exploit those advantages in a global arena in which you are no longer protected by your national borders.” Then governments try to position regions as “athletes in the Olympic Games of globalization.”

The message that has come through in this symposium, Mr. Pezzini observed, is that governments should not pursue sectoral approaches. “There should be multi-sectoral intervention, where investments are coordinated in order to exploit comparative advantage.” The tools are not subsidies, he added. They are investments to build public goods for communities. There is a growing realization that it is hard for companies to compete when they are alone and isolated, he said. They also need infrastructure to be competitive.

Governments are also adapting to new approaches to innovation, Mr. Pezzini said. They are taking into account that innovation is increasingly open. It requires interaction between different specialties.

To illustrate his point, Mr. Pezzini held out his cellular phone. The product is a collaboration by experts in different technologies, such as radio engineers who are experts in signals and telephone engineers who make sure those signals go to the right numbers. “Cocktail partners were required to put together the people in places where they could discuss with and see each other, to stop them when they want to kill each other again, and then to put them together again and launch a new discussion, after which you get an innovation.”

Not all government interventions promote such cross-fertilization. Mr. Pezzini noted that 80 percent of R&D tax credits in Mexico go to eight firms that specialize in the auto industry. Are such policies really needed to promote and diffuse innovation? “I don’t think so,” he said.

Another important new idea in promoting clusters, he said, is to combine different public investments in innovation and technology. If a region wants to create science centers and technopoles, then it should plan and design them with different actors that must come together. This requires new kinds of governance, Mr. Pezzini said.

He said he was impressed that in the United States seven federal agencies now sit at the same table to make sure policies succeed. A decade ago, most governments kept agencies separate and finance ministries decided which to support. Now, governments realize that investments in areas like infrastructure will be extremely unproductive if not coordinated with investments in areas like human capital.

New strategies also go beyond the old focus on creating macro-economic environments conducive to growth. Mr. Pezzini recalled that recently the U.S. government asked the OECD for advice on how to reduce unemployment in America. Researchers concluded that the biggest factors influencing employment were regulatory reform, flexibility and mobility of the labor market, and sound macro-economic policies. But the United States already ranked as best in the OECD in all of these areas. “Therefore, traditional answers cannot be used to address the problems of today,” Mr. Pezzini said. Other policies are needed that complement the macro environment.

How to carry out public governance of innovation strategies raises a number of questions, he noted. One is how to align the different actors. Should federal agencies give money to the states, or give them part of the money if they put in the other 50 percent? Should the parties set up performance indicators and then sit down three years later to discuss progress? And should money be removed if the efforts aren’t working? Should the process be transparent?

“This debate for me is new, is extremely important indeed, and I thank you for inviting me here,” Mr. Pezzini concluded.