In the previous chapters, the committee framed the numerous challenges and opportunities for defining and measuring the determinants of living well with chronic illness. This chapter describes the associated challenges of designing and implementing effective public policies aimed at living well with chronic illnesses.

First, the chapter defines health policy, which is aimed at improving the delivery of health care (clinical medicine) and public health, and describes the need for better integration between the two fields. It includes a brief description about the barriers to developing effective health policy, including budgetary challenges, and the lack of systematic evidence-based policy assessment, evaluation, and surveillance.

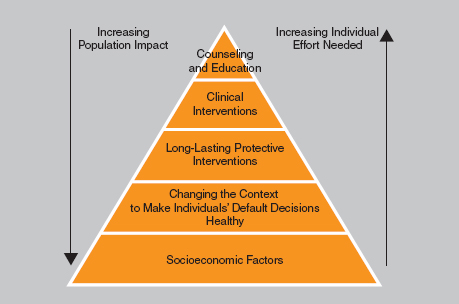

Next, the chapter identifies the range of public policies that have an impact on living well with chronic illness. Using Frieden’s pyramid of Factors that Impact Health (Frieden, 2010) as a framework, the chapter summarizes a continuum of policies ranging from structural (or distal) policies, which have the largest impact on the broad population of those who are chronically ill, to individual-level (or proximal) policy interventions, which have a more targeted impact on a smaller number of people.

Beginning with the base of Frieden’s pyramid (Frieden, 2010), the chapter highlights numerous public policies that have an impact on the ability of high-risk populations with chronic illnesses to live well. Numerous social policies have proven critical in maintaining function and independence for chronically ill populations who are most disadvantaged in terms of income

and/or disability. The recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges (2011) describes these policies and makes detailed recommendations about the need to review and revise various public health policies and laws in order to improve population health. Many of these policies and laws are designed to prevent illness in the general population and to help prevent further morbidity in those already chronically ill—for example, clean indoor air laws and smoking cessation interventions.

Extending through the tip of Frieden’s pyramid, the chapter concludes with policies that impact health care delivery and self-care, also important in supporting those with chronic illness to live well. Recently passed federal health reform, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), represents the most significant changes to health care policy since the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. Given the numerous provisions targeted to improving health care delivery and population health, the chapter describes aspects of the ACA that are particularly relevant to the well-being of those with chronic illness.

Finally, in order to promote synergistic improvements in public policies that have the potential to impact health, the chapter describes a broad Health in All Policies (HIAP) strategy that seeks to assess the health implications from both health and nonhealth public- and private-sector policies.

Defining Health Care (Clinical Medicine) and Public Health Policy

In general, public policy refers to the “authoritative decisions made in the legislative, executive, or judicial branches of government that are intended to direct or influence the actions, behaviors, or decisions of others” (Longest and Huber, 2010). Health policy is the subset of public policies that impacts health care delivery (clinical medicine) and public health (population health).

Most health policy in the United States is health care (clinical medicine) policy, aimed at regulating or funding the loosely coordinated mechanisms for the financing, insurance, and delivery of individual-level health care services (Hardcastle et al., 2011; IOM, 2011; Shi and Singh, 2010). Whereas public health focuses on the health status of broad populations across generations, clinical care focuses on individuals. The committee discussed the need to expand beyond this fairly simplistic view of health and in Chapter 1 provides a framework (Figure 1-1) for considering the relationship among determinants of health, the spectrum of health, and policies and other interventions that help those with chronic illness to “live well.”

To the extent that Americans often think in terms of their individual health status rather than in terms of population health, it may be understandable why policy makers focus on allocating resources and regulating

policy in health care services. However, the health and well-being of the individual and the health of the population are interrelated and interdependent. Choucair (2011) suggests that “maintaining two disciplinary silos (public health and clinical medicine) is not the answer. Bridging the gap is critical if we are serious about improving the quality of life of our residents…. [W]e will not be successful unless we translate what we learn in research all the way into public policy.” Many public policies that improve health, especially for those with chronic illness, could be provided more effectively and efficiently in a more integrated, better aligned health system (Hardcastle et al., 2011). The committee discusses the need for a more integrated health system in detail in Chapter 6 and provides several examples of partnerships among clinical care, public health, and community organizations that promote health for those with chronic illness.

Barriers to Effective Health Policy

As expressed in the recent IOM report (2011), “now is a critical time to examine the role and usefulness of the law and public policy more broadly, both in and outside the health sector, in efforts to improve population health.” The report noted the need for improvements in public policy as a result of several factors, including but not limited to developments in the science of public health; the current economic crisis and severe budget cuts faced by local, state, and federal government; the lack of coordination of health policies and regulations; recent passage of federal health reform (the ACA); and increasing rates of obesity in the U.S. population.

Defining the appropriate role of government, however, is at the heart of public policy making in the United States. Although Americans value their health, many also value their ability to make individual choices about their health care, health behavior, and quality of life. Accordingly, many policy makers place high priority on individual liberties and, concomitantly, a limited role for government. Policy makers balance multiple competing public policy interests, made more challenging in the current economic climate in which competition for resources is high. For this reason, it is critical to integrate health care policy with public health policy and reframe them both to be consistent with other societal values, such as prosperity, economic development, long-term investment, and overall well-being. Reminding policy makers in all sectors of government that “businesses can rise and fall on the strength of their employees’ physical and mental health, which influence[s] levels of productivity and, ultimately, the economic outlook of employers” (IOM, 2011) will help to emphasize the economic implications of population health. Given that two-thirds of U.S. health care spending is consumed by just 28 percent of people who have two or more chronic illnesses (Anderson, 2010), the country can avoid unnecessary costs and

poor health by addressing the underlying cause of illness (Hardcastle et al., 2011).

The data and analytic methodology for assessing effective public policy is often lacking, and demonstrating causality between policy interventions and their intended outcome is difficult, especially for interventions that require longitudinal follow-up and assessment. The IOM report For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges (2011) outlined several important large-scale policy initiatives targeting childhood disadvantage to prevent poor health in adulthood. Examples include “home health visiting programs, early stimulation in child care programs, and preschool settings (i.e., Early Head Start and Head Start)” (IOM, 2011). Yet questions about the long-term efficacy of many of these types of interventions remain (The Brookings Center on Children and Families and National Institute for Early Education Research, 2010). Chapter 4 provides a detailed description of a number of community-based initiatives aimed at improving the health and well-being of those with chronic illness.

An added challenge to developing effective health policy, which is in itself an iterative cyclical process, is the fact that tracking and evaluating policy implementation and efficacy are not done in a systematic fashion at the state or federal level. Instead, surveillance of various public policies occurs across government, foundations, the private sector, and various nonprofit organizations. The Kaiser Family Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the National Association for State Health Policy, and the Commonwealth Fund provide an abundance of information about current federal and state laws as they relate to chronic illness. In addition, such organizations as the Trust for America’s Health and the County Health Rankings help to inform local, state, and national policy across the determinants of multiple chronic conditions (MCCs). Yet, generally speaking, these organizations do not systematically assess how well specific state and federal laws are being implemented or how well they are working to achieve their stated goals. Alternatively, organizations focused on specific illnesses, such as the Arthritis Foundation, can effectively advocate for state and federal policies that impact their constituencies. What is missing is widespread collaboration between these two extremes, as well as a focus on policies that pertain directly to well-being and quality of life. Many organizations are only beginning to work in a collective fashion to achieve similar policy goals, such as living well with chronic illness.

Other nonprofit organizations, such as the National Council for State Legislatures (NCSL), track state policies that pertain to such chronic illnesses as diabetes. NCSL provides information about diabetes minimum coverage requirements for state-regulated health insurance policies, state Medicaid diabetes coverage terms and conditions, and an overview of federal funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to

state-sponsored diabetes prevention and control programs (NCSL, 2011). In addition, NCSL, the National Governors Association, the National Academy for State Health Policy, and other groups also track other state-level health policy issues, such as state implementation of federal health reform. According to NCSL, at least 32 states have enacted and signed laws specific to ACA health insurance implementation as of July 2011. These laws cover a wide variety of issues in at least 15 categories.

In addition to the need for better surveillance of public policy, research on the relationship between law and legal practices and population health and well-being is still developing (Burris et al., 2010). Moreover, questions about the cost-effectiveness of various health policies are paramount. Policy makers require evidence about effectiveness, projected outcomes, and value in order to judge the merits of proposed policies. However, concerns about using science to measure cost-effectiveness in health care delivery have led some policy makers to raise concerns about the rationing of health care services by the government (California Healthline, 2010). For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges (IOM, 2011) extensively evaluated how research could be used to improve public policy surveillance. The committee suggested that “research on the comparative effectiveness and health impact of public health laws and policies could be conducted by documenting geographic variation and temporal change in population exposure to specific policy and legal interventions.” The committee recommended that an interdisciplinary team of experts be given appropriate resources to evaluate evidence for outcome assessments of policies and regulations and derive new guidelines for setting evidence-based policy. Chapter 5 provides a detailed description and framework for chronic disease surveillance that will be required to adequately evaluate policies aimed at helping those with chronic illness to live well.

American Values in Public Policy

Even as new research establishes that social and environmental factors significantly influence health status, Americans often question this worldview (IOM, 2011). For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges (IOM, 2011) describes four “imperatives”—rescue, technology, visibility, and individualism—that influence American policy making. These imperatives tend to focus policy makers’ attention on crises or novel events that have a compelling narrative, and away from concepts more commonplace, such as “living well”:

1. Rescue imperative: people are more likely to feel emotionally connected to individual misfortune and circumstances, but less inclined to react to negative information conveyed in statistical terms.

2. Technology imperative: people find more appeal in cutting-edge biomedical technologies than in population-based interventions.

3. Visibility imperative: people take for granted public health activities that occur “behind the scenes” unless a crisis arises, such as influenza.

4. Individualism imperative: Americans generally value individualism, favoring personal rights over public goods.

CONTEXTUALIZING HEALTH POLICY

INTERVENTIONS: FRIEDEN’S PYRAMID

Although most interventions aimed to help people with chronic illness live well focus on the individual, the Health Impact Pyramid (Figure 3-1) illustrates why interventions focused more on public health may be beneficial as well (Frieden, 2010). The base of Frieden’s pyramid includes health-related socioeconomic factors, with interventions aimed at reducing poverty and increasing educational levels. The next level of the pyramid

FIGURE 3-1 Health Impact Pyramid. SOURCE: Frieden, T.R. 2010. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health 100(4):590–595. The Sheriden Press.

recommends changing the environmental context to prevent illness, using such interventions as water fluoridation and environmental changes to encourage physical activity. The third level involves one-time, or infrequent, protective interventions, such as vaccines to prevent infectious disease. The fourth and fifth levels of the pyramid include clinical interventions and counseling/educational interventions. The intervention levels differ in both the individual effort needed for the intervention to be successful and their potential impact. Moving down the pyramid, there is an inverse relationship: individual effort required decreases as the population impact increases. Although more individual approaches may be appropriate for helping those with chronic illness manage illness-specific aspects of their health (e.g., counseling and reminder systems to encourage diabetic patients to adhere to medication regimens), interventions further down will be of benefit as well (e.g., increasing access to facilities for physical activity can help those with arthritis be more physically active and improve their physical functioning). Each of these interventions can, and often does, have an impact on an individual’s overall well-being.

Policies Aimed at Socioeconomic Factors

Frieden’s pyramid (Figure 3-1) begins with a focus on socioeconomic factors. Persons with chronic illnesses need protection of their rights to accessibility of services, programs, public facilities, transportation, housing, and other necessities for independent living and having a high quality of life in addition to their public health and health care needs. Federal policies, such as the Ticket to Work and Self-Sufficiency program within the Medicaid system (Stapleton et al., 2008), or paid medical leave for employees and caregivers (Earle and Heymann, 2011) have proven instrumental in helping those with chronic illness live well.

These policies range from providing income support to low-income and disabled individuals—such as the Social Security Amendments of 1956, which created the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program—to transportation policies that require all new American mass transit vehicles to come equipped with wheelchair lifts (for example, the Urban Mass Transportation Act, 1970), to tax policies that preclude fringe benefits, such as health insurance, from being counted as taxable income, to community supports such as those provided through the Older Americans Act, such as nutrition assistance, home- and community-based services, as well as caregiver supports. The context of public law generally creates this environment. Although many of these broad social policies are expensive to implement and increasingly difficult to expand when resources are scarce, research suggests that there are associated cost savings as well as increased quality of life. Full description of the numerous policies that impact quality

BOX 3-1

Additional Examples of Public Policies That Impact Living

Well with Chronic Illness

Independent living support policy

• 1965—The (American) Vocational Rehabilitation Amendment authorizes federal funds for construction of rehabilitation centers, expansion of existing vocational rehabilitation programs, and creation of the National Commission on Architectural Barriers to Rehabilitation of the Handicapped.

• 1965—The Older Americans Act provides funding based primarily on the percentage of an area’s population 60 and older for nutrition and supportive home- and community-based services, disease prevention/health promotion services, elder rights programs, the National Family Caregiver Support Program, and the Native American Caregiver Support Program.

• 1978—Title VII of the Rehabilitation Act Amendments established the first federal funding for consumer-controlled independent living centers and the National Council of the Handicapped under the U.S. Department of Education.

• 1990—The Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resource Emergency Act was meant to help communities cope with the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Transportation policies

• 1970—The Urban Mass Transportation Act requires all new American mass transit vehicles to come equipped with wheelchair lifts. Although the American Public Transportation Association delayed implementation, regulations were issued in 1990.

of life is beyond the scope of this report. However, a number of significant policies that are critical to helping those with chronic illness and disability are provided (see Box 3-1).

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 and the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 were considered national civil rights bills for people with disabilities. The scope of these laws includes the public sector (federal, state, and local governments) and the private sector (businesses with 15 or more employees), mandating “reasonable accommodations” for workers with disabilities. The ADA contains four mandate areas: employment protection; public service, including transportation and accessibility; nondiscrimination in public accommodations and services offered by most private entities; and telecommunication services. Given the committee’s definition of “living well” as a self-perceived level of comfort, function,

Privacy policies

• 1996—The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act provided the first federal protections against genetic discrimination in health insurance. The act prohibited health insurers from excluding individuals from group coverage because of past or current medical problems, including genetic predisposition to certain diseases.

• 2008—The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act was designed to prohibit the improper use of genetic information in health insurance and employment. The act prohibits group health plans and health insurers from denying coverage to a healthy individual or charging that person higher premiums based solely on a genetic predisposition to developing a disease in the future. The legislation also bars employers from using individuals’ genetic information when making hiring, firing, job placement, or promotion decisions.

Access to health care policies

• 1965—Medicare and Medicaid, established through passage of the Social Security Amendments of 1965, provides federally subsidized health care to disabled and elderly Americans covered by the Social Security program. These amendments changed the definition of disability under the Social Security Disability Insurance program from “of long continued and indefinite duration” to “expected to last for not less than 12 months.”

and contentment with life, the role that the ADA has played in the lives of those with disability is immeasurable.

Although the ADA has proven essential for those with chronic illness, its implementation has significant disparities by condition. More specifically, analyses suggest that provisions of the ADA disproportionately underprotect people with psychiatric disabilities (Campbell, 1994). Research also has found that people with visual impairments rate the ADA lower than do people with hearing and mobility impairments (Hinton, 2003; Tucker, 1997). Furthermore, the “doubly disadvantaged,” those with poor education and job skills plus a disability, do not appear to benefit in the long term from the ADA (Daly, 1997). Overall, the ADA has narrowed the gaps among those with and without disabilities in the areas of education and political participation. However, the similar gap in employment has not narrowed. The employment rate for those of working age with a disability

is 75 percent of those with a nonsevere disability and 31 percent of those with a severe disability. For those without a disability, the employment rate is 84 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

Other major concerns that impact the ability of those with chronic illness to live well are income and housing: 27.9 percent of those of working age with disabilities live below the poverty level compared with 12.5 percent of the general population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). SSDI is available to those who have worked long enough to pay taxes and are deemed disabled, and Social Security Income (SSI) is available for those deemed disabled and poor. Both programs require that (1) the recipient be deemed unable to complete work done previously or able to adjust to other work and (2) the disability persists for at least one year in duration. In 2008, the average SSDI payment was $12,048 per year, or 116 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) for one person. Recent data suggest that for those on SSI income, housing costs consume somewhere between 60 and 140 percent of income (NAMI, 2010). Many with disabilities struggle to find affordable and accessible housing, despite the existence of disability-specific housing legislation and other U.S. Housing and Urban Development programs to provide affordable housing.

Caregivers of those with chronic illness often struggle with maintaining their own health and well-being as they care for their loved one. The Family and Medical Leave Act entitles eligible covered employees up to 12 weeks of job-protected, unpaid leave during any 12-month period in order to care for family members with a serious health illness or their own serious health illness; the employee maintains group health benefits during this leave. Even for those with the ability to maintain a job, recent data suggest that one of the largest causes of home foreclosures is a medical crisis. Specifically, a study of those going through home foreclosure in four states found that medical crises contributed to half of all home foreclosure filings (Robertson et al., 2008).

Public policies that address the next level of Frieden’s pyramid, changing the context in order to make individuals’ default decisions healthy, include state and local clean indoor air and smoke-free laws and ordinances as well as state tobacco taxes. Although the role of government in U.S. health care delivery has long been a contentious one (Starr, 1982), the case of tobacco control illustrates that a chronic disease risk factor can be amenable to U.S. public policy intervention. Data from the CDC celebrate “the 58.2 percent decrease in the prevalence of smoking among adults since 1964 [which] ranks among the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century” (IOM, 2011). As described in For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges (IOM, 2011), “the tobacco story also provides a rich example of a suite of public health interventions

(including the power to tax and spend, indirect regulation through litigation, and intervening on the information environment), several of them public policies, to improve population health, specifically by reducing mortality and morbidity due to its use.” As outlined in the 2000 Surgeon General’s Reducing Tobacco Use report (HHS, 2000), beginning in 1950, “the series of Surgeon General’s reports began meticulous documentation of the biologic, epidemiologic, behavioral, pharmacologic, and cultural aspects of tobacco use…. The past several years have witnessed major initiatives in the legislative, regulatory, and legal arenas, with a complex set of results still not entirely resolved.” The strides made in tobacco control have a direct impact on improving the well-being of those both with and without chronic illness.

Indeed, despite significant political obstacles, public health advocates have successfully developed and implemented public policy to prevent tobacco use at multiple levels of government. Halpin et al. (2010) outline a broad set of policies aimed at reducing demand for/restricting the supply of tobacco products that range from individual level interventions to broad societal interventions. Although the public health effort to lower tobacco use continues, the public policy lessons are generalizable to other areas in which policy action is needed in order to improve health outcomes. Specific policies include raising excise taxes on tobacco; lowering the cost of treatments for tobacco addiction; regulating exposure to environmental tobacco smoke; regulating the contents of tobacco products; regulating packaging and labeling; banning tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship; prohibiting tobacco sales to minors; regulating physical access to tobacco products; and eliminating illicit tobacco trade (Halpin et al., 2010).

Public policies that address the third level of Frieden’s pyramid and target long-lasting protective interventions include insurance mandates that require coverage of preventive services, like colonoscopies and immunizations. Those with functional impairment or disability are particularly susceptible to poor health behaviors given their mental, social, and economic burden as well as their family and caregiver stress. Growing evidence indicates that a comprehensive approach to prevention can save long-term health care costs, mitigate needless suffering, and improve overall well-being, but more evidence is needed to understand how these policies impact people with MCCs.

Examples of public policies that prevent chronic disease in the general population and reduce morbidity in those already living with a chronic illness are highlighted in Box 3-2. Chapter 4 on community-based intervention provides additional details on policies and interventions that affect lifestyle behaviors, screening and vaccination, and other inventions such as self-help and disease management.

BOX 3-2

Examples of Public Policies Aimed at

Preventing Chronic Disease

Increase physical activity

• Increased access to places for physical activity (e.g., walking trails in parks) (infrastructure)

• Enhanced school-based physical education classes (institutional policy)

• Urban design of neighborhoods with proximity to retail, schools, and recreation areas (zoning regulation)

• Point-of-service signs to increase stair walking (institutional policy)

• Street closures (institutional policy)

• Widening sidewalks (building codes)

• Bicycle paths (urban design, transportation, regulations)

• Creation of bicycle parking (institutional policy, building codes)

• Bicycle racks on trains and buses (institutional policy, transportation, regulations)

• Car, road, and fuel taxes (tax)

Improve diet

• Ban on use of trans fatty acids in restaurants (law)

• Menu labeling in restaurants (law)

• Removal of vending machines in schools (institutional policy)

• Adding salad bars at schools (institutional policy)

• Incentives for putting supermarkets in neighborhoods (zoning regulation)

• Creation of farmers’ markets (institutional policy)

• Limitation on advertising of high-caloric, low-nutrition foods directed at children (law)

• Tax on high-caloric, low-nutrition foods (tax)

SOURCE: Copyright © Katz, M.H. 2009. Structural interventions for addressing chronic health problems. Journal of the American Medical Association 302(6):683–685. All rights reserved.

Policies Aimed at Clinical Interventions

The burden of chronic disease is staggering. Chapter 2 summarizes the burdens experienced by those affected, which range from a number of debilitating medical illnesses to disease self-management challenges, accompanying psychological health issues, and frequent social consequences for employment, education, parenting, etc. Families of the chronically ill are also impacted. Hardships for family members often include caregiver stress and economic consequences. Some of these issues can be addressed by appropriate evidence-based public policies aimed at individuals, communities, and populations. However, meeting the multiple needs of these individuals

and their families remains an expensive proposition, and there is limited knowledge of which public policies are most instrumental in helping those with chronic illness to live well.

In terms of effective health care delivery, the Chronic Care Model (CCM) (Wagner et al., 1996) has long been a useful framework for attending to the multiple issues for managing chronic disease, ranging from self-management support to delivery system designs, decision support, information technology, community linkages, and health care organizations. The CCM model and its limitations are outlined in detail in Chapter 1. Five of the six elements in this model fall within the health care system, highlighting the need for better coordination among the elements of the CCM in a global care or support process and for more use of health information technology. Chapter 6 identifies particular ways in which community linkages can be used as part of a more comprehensive plan for self-management support (Ackermann, 2010).

Separate from limited models like the CCM, the current health system does not incentivize care coordination for those with chronic illness. Chapter 6 highlights aspects of the ACA aimed at government public health agencies, many of which currently provide health care services to the uninsured; with full implementation of the ACA anticipated in 2014, the law will provide access to health insurance for most Americans. However, the ACA does not mandate major changes in how the United States delivers and pays for most health care services but instead tests new and innovative models of reimbursement; this is described in more detail later in this chapter.

The current method of paying for most health care services in the United States continues to be fee-for-service (FFS), which creates financial incentives for doctors and hospitals to focus on the volume and intensity of services delivered rather than the quality, cost, or efficiency of care delivery (Council of Economic Advisers, 2009). Moreover, FFS does very little to support models like the CCM or the patient-centered medical home model (PCMH), which are centered on strong primary care. Starfield and others (Starfield, 2010; Starfield et al., 2005) have demonstrated that a strong primary care foundation can reduce costs and improve quality of care, prevent disease and death, and provide a more equitable distribution of health care services. In order to promote the delivery of high-value primary care and preventive services and reward improved outcomes, new models of provider payment that align incentives to support those with chronic illness while stabilizing and/or reducing total health care costs should be more broadly implemented (Bailit et al., 2010).

A crucial component of health system reform is fixing the current provider payment reimbursement system (Landon et al., 2010). There are a number of reimbursement models designed to better support and coordinate

care for those with chronic illness, many of which will be pilot-tested as part of federal health reform, outlined below. These include enhancing FFS payments to provide support for care coordination; comprehensive global payment models that share reimbursement across providers (Goroll et al., 2007); and hybrid reimbursement models that incorporate FFS, adjusted prospective payment, and performance-based compensation (Baker and Doherty, 2009). Many of the PCMH demonstration projects include a hybrid payment model (Bitton et al., 2010). Peer-reviewed evaluations of the various reimbursement models are provided in more detail in Chapter 6. Landon et al. (2010) point to the reality of monetary incentives, stating that “economic theory suggests that implementing appropriate incentives through payment reform will result in primary care practices evolving over time toward the medical home ideal.” The increased reimbursement can be used for a myriad of purposes: hiring care coordinators to support those with chronic illness; extending office hours to include evening and weekend availability; and purchasing or upgrading electronic health record (EHR) systems that support enhanced patient-provider communication and self-management.

As briefly described above, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148) and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act (P.L. 111-152)—together referred to as the Affordable Care Act or ACA—provide a number of reforms and opportunities that have the potential to improve the lives of individuals with chronic illness. In addition, the law gives new rights to those who have previously faced difficulties obtaining health insurance—a problem often faced by those living with chronic illness. For example, the law allows young adults under 26 to maintain coverage through their parents’ health insurance, ends lifetime and most annual limits on care, and gives patients access to recommended preventive services without cost sharing. Importantly for those with chronic illness, it also bans insurance companies from denying coverage because of a person’s preexisting medical illness.

A number of specific provisions are discussed below, and Annex 3-1 (at the end of the chapter) details a number of additional provisions that impact those living with chronic illness. In addition to the detailed description of the law provided below, in Chapter 6 the committee evaluates how the ACA can be used to help align public health and clinical care services in order to promote living well for those with chronic illness.

New Coverage Options and Subsidies to Purchase Insurance

By January 1, 2014, the ACA will require most individuals in the United States to obtain health insurance. Coverage options for the currently uninsured include the creation of state-based health insurance exchanges and the expansion of the Medicaid program. The Congressional Budget Office projects that 32 million people will be made newly eligible for insurance coverage either through their state’s exchange or through the Medicaid expansion. In addition, eligible individuals and families will receive tax credits to cover premiums and cost sharing for qualified health plans purchased in a state exchange.

The state insurance exchanges created through the ACA aim to create efficient and competitive health insurance markets through which individuals and small businesses can purchase health insurance coverage. All qualified health plans in the new exchanges will be required to offer the “essential health benefits package” as defined by the law and will include at least the following general categories (as well as the items and services covered within the categories): ambulatory patient services; emergency services; hospitalization; maternity and newborn care; mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment, prescription drugs, and rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices; laboratory services; preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management; and pediatric services, including oral and vision care.1 For many living with chronic illness, this new coverage provides important opportunities to access affordable, quality health insurance.

In addition to the new exchanges, starting January 1, 2014, Medicaid will be expanded to cover all individuals below 133 percent of the federal poverty level. Under the new Medicaid eligibility criteria, an estimated 14 million uninsured nonelderly adults and children will be eligible for Medicaid in 2014 (Ku, 2010). New Medicaid enrollees who qualify for Medicaid under the expansion are entitled to “benchmark” or “benchmark-equivalent” coverage.2 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary will define benchmark coverage, but this coverage must include all essential health benefits (as defined for the state exchange), including prescription drug coverage and mental health services.

![]()

1Qualified health plans operating in the state exchange are subject to the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Generally, the act requires that the financial requirements and treatment limitations imposed on mental health and substance use disorder benefits not be more restrictive than the predominant financial requirements and treatment limitations that apply to substantially all medical and surgical benefits.

2Benchmark coverage is based on Federal Employees Health Benefits insurance coverage, state employee coverage, and coverage offered by the health maintenance organization in the state that provides coverage for the largest number of non-Medicaid enrollees.

New Care Options for Those Living with Chronic Illness

A number of provisions in the ACA are targeted specifically to those living with chronic illness. For example, the law gives states an opportunity to offer Medicaid enrollees home- and community-based services and supports before individuals need institutional care. As of October 1, 2011, the new Community First Choice Option now provides states with the option to offer, through a Medicaid state plan amendment, home- and community-based attendant services and supports for certain Medicaid enrollees with disabilities whose income is up to 150 percent of FPL. These services and supports are intended to assist disabled individuals in accomplishing activities of daily living (such as eating, toileting, grooming, dressing, bathing, and transferring), instrumental activities of daily living (such as meal planning and preparation; managing finances; shopping for food, clothing, and other essential items; and performing household chores), and health-related tasks.

In addition, the new Medicaid health home provision will provide a new care option for those living with chronic illness. Beginning January 1, 2011, states were allowed to amend their state Medicaid plan and to assign Medicaid enrollees with chronic illnesses to a “health home” selected by the beneficiary. Health home services, provided by a designated provider, a team of health care professionals, or a health team, include (1) comprehensive care management, (2) care coordination and health promotion, (3) comprehensive transitional care, (4) patient and family support, (5) referral to community and social support services, and (6) use of health information technology to link services. Medicaid enrollees eligible for these health home services must meet one of three categories: (1) have at least two chronic illnesses (including mental health illnesses and substance abuse disorders), or (2) have one chronic illness and be at risk of developing a second one, or (3) have a serious and persistent mental health illness.

Finally, the ACA made important new investments in community health centers, which predominantly serve individuals and families with low income, many of whom have chronic illnesses. Currently, there are approximately 1,100 community health centers nationwide, serving 19 million patients at 7,900 sites. The ACA provided an additional $11 billion over 5 years for community health centers, which provide preventive and primary care to patients of all ages regardless of ability to pay. The majority of these mandatory dollars—$9.5 billion—will go to create new centers and expand care at existing centers. Another $1.5 billion will support construction and renovation projects.

New Care Concepts

Because the delivery of care is often fragmented, the ACA authorizes a number of new care concepts that are designed to improve care coordination and delivery especially for those living with chronic illness. For example, the ACA established a new entity within Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMI). CMI will test various innovative payment and service delivery models to ascertain if and how these models could reduce program expenditures while preserving or enhancing the quality of care provided to individuals enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

CMI intends to prioritize testing models that could significantly aid those with chronic illness, including models that

• use comprehensive care plans;

• promote care coordination between providers;

• support care coordination for chronically ill patients at high risk of hospitalization;

• use medication therapy management;

• establish community-based health teams;

• promote patient decision-support tools;

• fund home health providers who offer chronic care management;

• promote greater efficiency in inpatient and outpatient services; and

• use a diverse network of providers to improve care coordination for individuals with two or more chronic illnesses and a history of prior hospitalization.

As outlined by CMI, the focus falls under three major areas: (1) patient care models (“developing innovations that make care safer, more patient-centered, more efficient, more effective, more timely, and more equitable”); (2) seamless coordinated care models (“models that make it easier for doctors and clinicians in different care settings to work together to care for Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP beneficiaries”); and (3) community and population health models (“steps to improve public health and make communities healthier and stronger”). CMI will test models that promote better clinical care and health outcomes as well as reduce costs.

In addition to the creation of CMI, the ACA creates a new Medicare Shared Savings Program to incentivize groups of providers and suppliers to work together through accountable care organizations (ACOs). The goal of the shared savings program is to promote accountability and better care coordination for Medicare FFS beneficiaries. Starting January 1, 2012, professionals who organize into certified ACOs are eligible to receive additional

payments for shared savings if the ACO: (1) meets the quality performance standards set by the HHS secretary and (2) spends below the established benchmark amount for a given year. Chapter 6 provides detailed information about how ACOs could be used to incentivize care coordination among multiple types of providers, including governmental public health agencies (GPHAs) and community-based organizations.

ACA Prevention Policies

The ACA also includes provisions to prevent illness. Preventing disease is especially important for those living with chronic illness.

The ACA establishes a National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council to prioritize prevention across the federal government. The council, composed of senior officials across government, is designed to evaluate and coordinate prevention activities and the focused strategy across departments of promoting the nation’s health. As outlined in the IOM report For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges (IOM, 2011), the council:

1. Creates a structure that specifically crosses government lines and brings different sectors of government to the table to talk about health in a structured way.

2. Engages both the legislative and executive branches at very high levels in an ongoing fashion.

3. Focuses on creation and agreement on strategy to achieve outcomes, one of the key points in the committee’s first report.

4. Enables engagement of a broader range of nongovernment interests and input through an advisory mechanism.

In addition, the ACA contains multiple provisions to strengthen coverage of preventive services, both inside and outside the new health insurance exchanges. As of January 1, 2011, all new private insurance plans are required to cover a range of preventive services with no cost sharing, including any services given an A or B recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); any vaccination recommended by CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; and certain preventive services for children, adolescents, and women.3

As of January 1, 2011, Medicare will offer full coverage for an “annual

![]()

3These provisions do not apply to health plans that are grandfathered—meaning that existing health plans are exempt as long as they do not change specific factors detailed in regulation, such as cost sharing. As existing health plans make changes over the next several years, it is expected that eventually most plans will fall under the requirement.

wellness visit” that includes a health risk assessment and customized prevention plan. In addition, all USPSTF-recommended services covered under Medicare must be provided with no cost sharing. In the Medicaid program, in 2013 and later, states that cover USPSTF-recommended services will receive a 1 percent enhancement to their federal match for those services. In addition, in 2013 and 2014, the ACA requires state Medicaid programs to pay primary care physicians for primary care services at the same rate, or greater, as the Medicare payment rate for these services.

In addition to strengthening coverage of preventive services, the ACA created the Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF), which provides mandatory funding for public health. The PPHF was set at $500 million in fiscal year 2010 and will increase to an annual total of $2 billion for 2015 and all ensuing years. To date, the PPHF has been used to strengthen the health and public health workforce, expand existing Public Health Service Act programs, bolster public health infrastructure through grants to states, and create and maintain new health promotion programs. The most prominent of these is the Community Transformation Grant (CTG) program, which aims to support communities in creating comprehensive change in the factors that affect people’s health across multiple environments.

The CTG program authorizes the HHS secretary to award competitive grants to state and local governmental agencies and community-based organizations for implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of evidence-based community preventive health activities. These community prevention activities will be aimed at reducing chronic disease rates, preventing the development of secondary illnesses, addressing health disparities, and developing a stronger evidence base of effective prevention programming. Not only is this investment in chronic disease prevention unprecedented; it also represents an opportunity to transform how communities and government work together to solve large complex problems, like preventing chronic disease, reducing health inequities, and (potentially) containing health care costs. In September 2011, HHS awarded $103 million in funding to 61 recipients through the CTG program, and a concerted effort is under way to extract early results from the program that demonstrate impact.

HEALTH IN ALL POLICIES AND HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENTS

The committee discussed the need to think broadly about how public policy can improve the lives of those with chronic illness. The health research community typically focuses its attention on traditional health agencies, such as HHS or state and local health agencies. However, there is a growing recognition that policy decisions across a broad range of government agencies can influence human health, positively or negatively. The concept of Health in All Policies (HIAP) reflects this recognition and

underscores the importance of considering the links between health and a wide set of government policies.

In some fields, the link to health is well established. For example, environmental factors can influence human health and development in a myriad of ways. Accordingly, there is a robust field of environmental health research, and environmental policies are often developed in ways that take into account the potential impact on health. In other policy fields, understanding the intersection with health is a newer concept. For example, transportation policy has not traditionally been a major area of research interest for health researchers, despite the fact that transportation access and design can have profound impacts on the health of individuals and communities. For example, the availability of public transportation decreases harmful pollution, creating safe throughways for “active transportation,” such as biking; walking can increase physical activity and improve health; providing affordable transportation options in low-income communities improves access to jobs and to healthful food outlets.

Key to the successful achievement of a HIAP approach is avoiding unidirectional benefits. That is, the goal is not simply to bend policy decisions in all areas to suit the demands of the health research and advocacy community. Rather, the interrelationships between health and other social goods mean that the same policies that promote health will, in many cases, also serve other policy goals. For example, improved physical fitness is broadly considered to be a necessary response to address the child obesity epidemic in America. At the same time, improved physical fitness has been linked to improved academic performance. Therefore, school-based programs that offer time and opportunity for safe physical exercise could potentially improve children’s health as well as their academic performance.

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Government of South Australia convened an International Meeting on Health in All Policies. The meeting drew on more than two decades of WHO work developing the concept of intersectoral collaboration for health. The meeting resulted in the “Adelaide Statement on Health in All Policies,” which urges leaders and policy makers to “integrate considerations of health, well-being, and equity during the development, implementation, and evaluation of policies and services” (Krech and Buckett, 2010).

Building on the work of WHO, several countries have taken broad action to shift policy making toward the HIAP approach. The European Union (EU), for example, adopted the HIAP framework as official policy in 2006, building on successful implementation of a robust HIAP agenda developed in Finland (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2006; Puska and Ståhl, 2010). Europe now has an explicit policy that a health impact assessment will apply to all new key EU policies (Koivusalo, 2010). The HIAP approach has

proven successful in several EU member states (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2006). For example, concurrent changes in agricultural, food manufacturing, and commercial policy in Finland led to a greatly improved Finnish diet (e.g., reduced fat content, increased fruit and vegetable consumption), leading to a drastic reduction in blood cholesterol levels; this produced an 80 percent reduction in annual cardiovascular disease mortality rates, increasing life expectancy by 10 years (Puska and Ståhl, 2010).

In addition to European countries, several of the Canadian Provinces have adopted a HIAP framework. Québec, for example, enacted a law in 2001 that requires all agencies to consult the Minister of Health and Social Services when they are formulating laws or regulations that could have an impact on health (Chomik, 2007). Based on early successes in the provinces, the Health Council of Canada is in the process of bringing the HIAP strategy to the national level through a “Whole-of-Government” initiative (Health Council of Canada, 2010).

The concept of HIAP has not gained as much traction in the United States compared with Europe and Canada (Collins and Koplan, 2009). However, interest in the topic is slowly growing, and HIA work is under way at the University of California, Los Angeles, the San Francisco Department of Public Health, and CDC. In October 2004, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and CDC came together to host a workshop in Princeton including domestic and international HIA experts to determine the steps needed to push the HIA field forward in the United States (CDC, [b]).

California has recently begun to shift its focus toward the HIAP framework. In 2010, Governor Schwarzenegger established a Health in All Policies Task Force charged with “identifying priority actions and strategies for state agencies to improve community health while also advancing the other goals of the state’s Strategic Growth Council” (California Health in All Policies Task Force, 2010). The task force has identified numerous opportunities for cross-sector policies to improve health and well-being, including incorporating safety considerations for pedestrians and bikers into street designs; ensuring access to smoke-free environments; and leveraging government spending to support healthy eating by using the state’s procurement policy to incentivize healthier food concessions on state property. Furthermore, the task force has had success forming relationships and building links between various sectors, which will form the basis of their future work.

Throughout the European and Canadian governments that have adopted the HIAP approach, Health Impact Assessments (HIAs) have been used as a primary tool for evaluating how policies and actions outside the health sector will impact population health. According to WHO, a Health Impact Assessment is a “means of assessing the health impacts of policies,

plans, and projects in diverse economic sectors using quantitative, qualitative and participatory techniques” (WHO, [a]). In addition, HHS recommends HIAs as a planning resource for implementing Healthy People 2020, recognizing that HIAs can provide recommendations to increase positive health outcomes and minimize adverse health outcomes (CDC, [a]).

As the definition suggests, an HIA can be applied to many different types of policy decisions. Doing an HIA of a policy may mean assessing the likely impacts of a federal, state, or local law; a regulation issued by an administrative agency at any of these levels; or the manner in which a law or regulation is implemented. An HIA of a plan could refer to any public-or private-sector plan, and an HIA of a project can refer to a wide range of construction, economic, or other projects.

In general, an HIA is performed before the policy, plan, or project is implemented. The goal is to identify any potential impact on health before it is too late to change course. Although the emphasis of an HIA is often on preventing or mitigating any potential negative consequences, an HIA can also be used to optimize health benefits or to identify potential missed opportunities to improve health.

A challenging but promising element of HIAs is the need to collaborate across sectors and disciplines. For example, an assessment of the potential health impact of a new highway project may require involvement of health, environmental, and transportation experts. The health experts alone may need to include epidemiologists, community health experts, and physicians. In addition, these experts must interact extensively with policy makers and community members in order to meaningfully assess potential impacts. This kind of interdisciplinary approach can lead to better decision making with regard to the current project. Furthermore, it can inform public health experts about a broad range of other policy areas, positioning them to better identify opportunities for health improvement in the future (Rajotte et al., 2011).

The challenge of living well with chronic illness is shared by individuals and families, communities, health care providers, workplaces, organizations, and communities. Numerous public policies are critical to maintaining function and independence for chronically ill populations who are most disadvantaged in terms of income and/or disability for living well with chronic illness. These include important social policies and programs like SSI, SSDI, and the ADA, as well as numerous other public policies that create healthy environments in which to live.

There are also a number of health care policies that directly impact those with chronic illness through better coordination of health care delivery,

many of which were included in recently passed federal health reform, the ACA. However, a system of coordinated policies and supports to assist those with chronic illness to live well is rare and not broadly considered by many policy makers. Better integration of health care policy and public health policy and assessing which policies are most effective at improving the function and well-being of those with chronic illness can ultimately lead to better health and economic outcomes.

In order to assist those with chronic illness to live well, the model adopted by the committee for this report and outlined in Chapter 1 (Figure 1-1) highlights the need to understand the complicated relationship among myriad determinants of health, health policies and other interventions, and the spectrum of health status. Adopting a HIAP strategy provides an opportunity to apply this model. Given its interdisciplinary approach to policy making, the HIAP framework creates synergistic improvements in overall health status via the assessment of the health implications from both health and nonhealth public- and private-sector policies. As such, HIAP can help to integrate health care and public health policy and better coordinate with various social supports and programs that are critical in helping those with chronic illness to function independently and live well.

The statement of task question asks what policy priorities could advance efforts to improve life impacts of chronic disease. In response, the committee makes two recommendations, derived from the discussion above.

Recommendation 7

The committee recommends that CDC routinely examine and adjust relevant policies to ensure that its public health chronic disease management and control programs reflect the concepts and priorities embodied in the current health and insurance reform legislation that are aimed at improving the lives of individuals living with chronic illness.

Recommendation 8

The committee recommends that the secretary of HHS and CDC explore and test a HIAP approach with HIAs as a promising practice on a select set of major federal legislation, regulations, and policies, and evaluate its impact on health related quality of life, functional status, and relevant efficiencies over time.

ANNEX 3-1 The Affordable Care Act: Provisions Impacting Chronic Illness

|

Provision |

Description |

|

Title I |

|

|

Extension of Dependent |

Mandates all group health plans and health insurance issuers offering group or individual health insurance that also offers dependent coverage to allow dependents to remain on their parent’s health insurance until they turns 26 years of age. |

|

Appeals Process |

Group health plans and health insurance issuers offering group or individual health insurance coverage must implement an effective internal appeals process for coverage determinations and claims, including appropriate notice of the process and the availability of any consumer assistance to help enrollees navigate their appeals. The plan must allow enrollees to review their files, present evidence and testimony as part of the appeals process, and receive continued coverage pending the outcome of the appeal. |

|

Health Insurance Consumer |

Grants to states or Health Benefit Exchanges to establish, expand, or offer support for offices of health-consumer assistance or health insurance ombudsmen programs. |

|

National Diabetes Prevention |

Authorizes a national program focused on reducing preventable diabetes in at-risk, adult populations. |

|

Immediate Access to Insurance for Uninsured Individuals with a Pre-existing Condition |

Temporary high-risk health insurance pools have been established for individuals who have preexisting conditions and have been uninsured for at least 6 months. Pools provide health insurance coverage to eligible individuals; cover at least 65 percent of the costs of benefits; ensure that the out-of-pocket expense limit is no greater than the limit for high-deductible plans; vary premiums only by family structure, geography, actuarial value of the benefit, age, and tobacco use; and include an appeals process to enable individuals to appeal decisions under this section. |

|

Closing the Medicare |

Medicare beneficiaries who reached the Medicare prescription drug coverage gap or “doughnut hole” in 2010 received a $250 rebate. To close the “doughnut hole,” coinsurance for generic drugs in the coverage gap will be reduced beginning in 2011, and a reduction in coinsurance for brand-name drugs in the gap begins in 2013. |

|

Affordable Choices of Health |

Each state must establish an American Health Benefit Exchange and a Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) Exchange to facilitate the purchase of qualified health plans. |

|

Title II |

|

|

Medicaid Expansion: |

New eligibility for Medicaid beginning on January 1, 2014, for individuals under age 65 earning an income that does not exceed 133 percent of the federal poverty level. |

|

Community First Choice |

An optional Medicaid benefit through which states could offer home- and community-based attendant services and supports to Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities and whose income does not exceed 150 percent of the federal poverty line for activities of daily living beginning October 1, 2011. |

|

Removing Barriers to Home- |

This provision gives states the option to provide more types of services through a state plan amendment (rather than a Medicaid waiver) for qualified disabled Medicaid individuals. They can provide targeted services to specific populations and extend full Medicaid benefits to individuals receiving home- and community-based services, but they may not limit the number of individuals eligible for home- and community-based services. |

|

Money Follows the Person Rebalancing Demonstration Program (MFP) |

Extends the “Money Follows the Person Rebalancing Demonstration” through September 30, 2016, and adjusts the time period of required institutional residence (individuals must reside in an inpatient facility for no less than 90 consecutive days). |

|

Providing Federal Coverage and Payment Coordination for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries |

The Federal Coordinated Care Office, housed in CMS, will bring together officials of the Medicare and Medicaid programs to more effectively integrate benefits under these programs and to improve coordination between federal and state governments for individuals eligible for benefits under both Medicare and Medicaid (dual eligibles). |

|

State Option to Provide Health Homes for Enrollees with Chronic Conditions |

States have the option to amend their Medicaid benefits to enroll Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic illnesses into a health home selected by the beneficiary (including services that are provided by a designated provider, a team of health care professionals, or a health team). |

|

Title III |

|

|

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program |

Establishes a value-based purchasing (VBP) program for hospitals participating in Medicare starting in fiscal year 2013. Under this program, a percentage of the hospital payment is tied to hospital performance on quality measures related to common and high-cost conditions. |

|

The National Strategy for Quality Improvement in Health Care (“National Quality Strategy”) |

A national strategy to improve the delivery of health care services, patient health outcomes, and population health, including a comprehensive strategic plan to achieve priorities identified by the HHS secretary. |

|

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation |

This new center will test various innovative payment and service delivery models to determine how these models reduce program expenditures while preserving or enhancing the quality of care provided to individuals enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. |

|

Medicare Shared Savings Program |

A program that incentivizes groups of providers and suppliers to work together through accountable care organizations (ACOs) with the goal of promoting accountability, and thus better care coordination, for Medicare fee-for-service patient populations. |

|

National Pilot Program on Payment Bundling |

A national pilot program encouraging hospitals, doctors, and postacute care providers to improve patient care and achieve savings for the Medicare program through bundled payment models. |

|

Extension for Specialized Medicare Advantage Plans for Special Needs Individuals |

Extends the Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plan (SNP) program through 2013. |

|

Establishing Community Health Teams to Support the Patient-Centered Medical Home |

Grants to states, state-designated entities, and Indian tribes to establish community health teams. The health teams will make it possible for local primary care providers to better address disease prevention and chronic illness management by facilitating collaboration between these providers and existing community-based health resources. |

|

Medication Management Services in Treatment of Chronic Disease |

A grant program for medication management services provided through the Patient Safety Research Center (Section 3501) to aid pharmacists in implementing medication management services for the treatment of chronic illnesses. |

|

Patient Navigator System |

“Patient navigators” will coordinate health care services needed for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic illnesses. Patient navigators will also facilitate the involvement of community organizations in assisting individuals who are at risk for or who have chronic illnesses to receive better access to high-quality health care services. |

|

Title IV |

|

|

National Prevention Council |

The National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council’s main responsibilities will include coordination and leadership at the federal level and among all federal departments and agencies with respect to prevention, wellness, and health promotion practices, the public health system, and integrative health care in the United States; development of a national prevention strategy; and recommendations to the president and Congress concerning the nation’s most pressing health issues. |

|

Prevention and Public Health Fund |

Establishes a Prevention and Public Health Fund in HHS. The fund will provide for an expanded national investment in prevention and public health programs to improve health and help contain health care costs. |

|

Medicare Personalized Prevention Plan Demonstration Project Concerning Individualized Wellness Plan |

Medicare must cover annual wellness visits and personalized prevention plan services with the creation of an individual plan that includes completion of a health risk assessment (HRA) and takes into account the results of the HRA. |

|

Removal of Barriers to Preventive Services in Medicare |

Medicare will pay 100 percent (waiving beneficiary coinsurance and deductibles) for covered preventive services if the services are recommended with a grade of A or B by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. |

|

Improving Access to Preventive Services for Eligible Adults in Medicaid |

Medicaid diagnostic, screening, preventive, and rehabilitation services are expanded to include approved clinical preventive services, recommended adult vaccinations, and any medical and remedial services recommended by a physician for the maximum reduction of physical or mental disability and restoration of an individual to the best possible functional level. |

|

Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Disease in Medicaid |

A program to award grants to states to provide incentives for Medicaid beneficiaries who participate in programs and demonstrate changes in health risk and outcomes by meeting specific targets. |

|

Community Transformation Grants |

Grants awarded to finance the policy, environmental, programmatic, and infrastructure changes needed to promote healthy living and reduce disparities in the community. |

|

Healthy Aging, Living Well; Evaluation of Community-Based Prevention and Wellness Programs for Medicare Beneficiaries |

Grants awarded to state or local health departments for a 5-year pilot program to provide public health and community interventions, community preventive screenings, clinical referrals for individuals with chronic illness risk factors, and other preventive services to individuals who are between ages 55 and 64. |

|

Employer wellness programs |

Programs to expand use of evidence-based prevention and health promotion approaches in the workplace. |

|

Title V |

|

|

State Health Care Workforce Development Grants |

A competitive health care workforce development grant program to enable state partnerships to complete comprehensive planning and to carry out activities leading to coherent and comprehensive health care workforce development strategies at the state and local levels. First, for planning grants to help states plan for current and future health care workforce needs and, second, for implementation grants to help state partnerships implement activities that will result in a coherent and comprehensive plan for health care workforce development, addressing current and projected workforce demands in the state. |

|

Training Opportunities for Direct Care Workers |

A grant program to fund eligible entities to provide new training opportunities for direct care workers who are employed in long-term care settings and agree to work in the field of geriatrics, disability services, long-term services and supports, or chronic care management for a minimum of 2 years following completion of the assistance period. |

|

Grants to Promote the Community Health Workforce |

A grant program to support community health workers and to promote positive health behaviors and outcomes for populations in medically underserved communities. |

|

Co-Locating Primary and Specialty Care in Community-Based Mental Health Settings |

Grants for coordinated and integrated services through the colocation of primary and specialty care in community-based mental and behavioral health settings. |

|

Title VI |

|

|

Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute |

A private, nonprofit institute to advance research on the comparative clinical effectiveness of health care services and procedures to prevent, diagnose, treat, monitor, and manage certain diseases, disorders, and health conditions. This research will assist patients, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers in making informed health decisions. |

Ackermann, R.T. 2010. Description of an integrated framework for building linkages among primary care clinics and community organizations for the prevention of type 2 diabetes: Emerging themes from the CC-Link study. Chronic Illness 6(2):89–100.

Anderson, G. 2010. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Bailit, M., K. Phillips, and A. Long. 2010. Paying for the Medical Home: Payment Models to Support Patient-Centered Medical Home Transformation in the Safety Net. Seattle, WA: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative.

Baker, B., and R. B. Doherty. 2009. Reforming Physician Payments to Achieve Greater Value in Health Care Spending: A Position Paper of the American College of Physicians. http://acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/policy/pay_reform.pdf (accessed November 3, 2011).

Bitton, A., C. Martin, and B. Landon. 2010. A nationwide survey of patient centered medical home demonstration projects. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25(6):584–592.

Burris, S., A.C. Wagenaar, J. Swanson, J.K. Ibrahim, J. Wood, and M.M. Mello. 2010. Making the case for laws that improve health: A framework for public health law research. Milbank Quarterly 88(2):169–210.

California Health in All Policies Task Force. 2010. Report to the Strategic Growth Council. http://sgc.ca.gov/HIAP/docs/publications/HIAP_Task_Force_Report.pdf (accessed November 3, 2011).

California Healthline. 2010. GOP Launches Criticism of Berwick’s Nomination as CMS Administrator. http://www.californiahealthline.org/articles/2010/5/13/gop-launches-criticism-of-berwicks-nomination-as-cms-administrator.aspx (accessed September 22, 2011).

Campbell, J. 1994. Unintended consequences in public policy: Persons with psychiatric disabilities and the Americans with disabilities act. Policy Studies Journal 22(1):133–145.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (a). Designing and Building Healthy Places. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/ (accessed January 16, 2012).

CDC (b). Health Impact Assessment. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/factsheets/Health_Impact_Assessment_factsheet_Final.pdf (accessed January 16, 2012).

Chomik, T. 2007. Lessons Learned From Canadian Experiences With Intersectoral Action to Address the Social Determinants of Health. Ottawa, ON: The Public Health Agency of Canada. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/isa_lessons_from_experience_can.pdf (accessed December 15, 2011).

Choucair, B. 2011. Feinberg PPH: Commencement Address Given by Bechara Choucair, May 4, 2011. http://adonis49.wordpress.com/2011/05/22/feinberg-pph-commencement-address-given-by-bechara-choucair/ (accessed November 2, 2011).

Collins, J., and J. P. Koplan. 2009. Health impact assessment. Journal of the American Medical Association 302(3):315–317.

Council of Economic Advisors. 2009. The Economic Case for Health Care Reform. http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/cea/TheEconomicCaseforHealthCareReform (accessed January 16, 2012).

Daly, M.C. 1997. Who is protected by the ADA? Evidence from the German experience. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 549(1):101–116.

Earle, A., and J. Heymann. 2011. Protecting the health of employees caring for family members with special health care needs. Social Science and Medicine 73(1):68–78.

Frieden, T. R. 2010. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health 100(4):590–595.

Goroll, A.H., R.A. Berenson, S.C. Schoenbaum, and L.B. Gardner. 2007. Fundamental reform of payment for adult primary care: Comprehensive payment for comprehensive care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22(3):410–415.

Halpin, H.A., M.M. Morales-Suárez-Varela, and J.M. Martin-Moreno. 2010. Chronic disease prevention and the new public health. Public Health Reviews 32(1):120–154.

Hardcastle, L.E., K.L. Record, P.D. Jacobson, and L.O. Gostin. 2011. Improving the population’s health: The affordable care act and the importance of integration. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 39(3):317–327.

Health Council of Canada. 2010. Stepping It Up: Moving the Focus from Health Care in Canada to a Healthier Canada. Toronto, ON: Health Council of Canada. http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/docs/rpts/2010/promo/HCCpromoDec2010.pdf (accessed December 15, 2011).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2000. Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Hinton, C.A. 2003. The perceptions of people with disabilities as to the effectiveness of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 13(4):210.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Koivusalo, M. 2010. The state of Health in All policies (HIAP) in the European Union: Potential and pitfalls. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 64(6):500–503.

Krech, R., and K. Buckett. 2010. The adelaide statement on Health in All Policies: Moving towards a shared governance for health and well-being. Health Promotion International 25(2):258–260.

Ku, L. 2010. Ready, set, plan, implement: Executing the expansion of Medicaid. Health Affairs 29(6):1173–1177.