Surveillance, one of the three core functions of public health, is defined as the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of data regarding a health-related event for use in public health action to reduce morbidity and mortality and to improve health (German et al., 2001; IOM, 1988). During the latter half of the 20th century, much of the focus of surveillance activities in the United States was on describing variations in the major causes of death and associated risk factors for fatal diseases. The results of these surveillance activities have been used to guide research investments and subsequent public health and health care interventions to address the major causes of mortality, including cardiovascular diseases and cancer; the associated chronic diseases, including obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia; and behavioral risk factors, including poor diet, physical inactivity, and smoking.

Life expectancy has improved over the past century, primarily as a result of public health interventions, such as tobacco control efforts, that have reduced the risk of the leading chronic diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, and cancer (Remington and Brownson, 2011). More recent evidence suggests that the increases in life expectancy during the past 20 years have come from improvements in disease management rather than in disease prevention (McGovern et al., 1996). However, mortality data from 2000 to 2007 demonstrate wide variation in life expectancy across counties in the United States and an overall relative decline in life expectancy for most communities compared with other nations (Kulkarni et al., 2011).

In addition to life expectancy, available evidence suggests that self-reported health status has not improved among retirees (Hung et al., 2011) or has declined in the general population (Jia and Lubetkin, 2009; Zack et al., 2004) and persons with certain chronic illnesses (Pan et al., 2006). However, these findings are not consistent (Salomon et al., 2009), as some data suggest that the prevalence of disability is decreasing (Manton, 2008), and in some surveys health status is improving (Salomon et al., 2009), over time. These disparate findings likely result from lack of standardized methods of measurement of the complex components and determinants of health status and disability (NRC, 2009), and they suggest that the current surveillance systems are insufficient for tracking progress in efforts to monitor trends in quality of life in the United States overall or within communities.

Despite uncertainty about trends in quality of life in the United States, the evidence is clear that more people are living with chronic illnesses as a result of increasing prevalence of some illnesses (e.g., obesity) and longer survival among patients diagnosed with chronic illness. Moreover, the rising costs of health care, along with evidence from research focused on patterns of health care utilization and costs, have focused attention on the societal burden of chronic diseases, particularly multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) (Tinetti and Studenski, 2011). Together, the aging of the population, the decline in relative life expectancy and possibly the quality of life, and unsustainable increases in health care costs combine to create a rapidly growing burden of chronic illness that demands more comprehensive surveillance beyond mortality and risk factors to address these problems.

The goal of living well with chronic illness and efforts to control the growing societal burden of chronic illness start with enhanced surveillance to provide data necessary to plan, implement, and evaluate effectiveness of interventions at the individual and population levels. This chapter has several objectives:

1. To describe a conceptual framework for chronic disease surveillance.

2. To describe how public health surveillance may be used to inform public policy decisions to improve the quality of life of patients living with chronic illnesses.

3. To examine current data sources and methods for surveillance of certain chronic diseases and identify gaps.

4. To describe potential for surveillance system integration.

5. To describe future data sources, methods, and research directions for surveillance to enhance living well with chronic illness.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR CHRONIC

DISEASE SURVEILLANCE

The ultimate goal of public health is to promote health and prevent disease occurrence or to limit progression from preclinical to symptomatic disease through primary and secondary prevention, respectively. Health promotion is the process of enabling people to gain increasing control over and improve their health. Primary prevention is usually addressed through interventions targeting lifestyle risk factors or environmental exposures among illness-free persons, including smoking, physical inactivity, and overweight/obesity. Secondary prevention among asymptomatic persons with preclinical illness may include a range of interventions comprised of early detection, immunizations, and chemoprevention.

Because of the public health emphasis on health promotion and disease prevention (especially primary and secondary prevention), chronic disease surveillance has traditionally focused on major risk factors for disease and the occurrence of chronic diseases. However, although primary and secondary prevention may have relevance for persons with chronic illnesses to prevent the development of other comorbid illnesses, a more immediate concern for individuals is how to live well, which involves a balance between their experience living with chronic illness(es) and associated costs (i.e., value).

Moreover, from a societal perspective, interventions to improve the patient experience need to be cost-effective and contribute to improving the health of the population. Thus, there is a strong rationale for expanded surveillance of chronic diseases to measure not only the factors that increase the “upstream” risk of chronic diseases but also the relevant health “downstream” outcomes associated with living well with chronic illness (Porter, 2010).

Table 2-1 provides an excellent framework for establishing a comprehensive chronic disease surveillance system. Such a surveillance system should collect data along the entire chronic disease continuum—from upstream risk factors to end of life care and for the purposes of promoting living well among persons with chronic illness. Such systems should collect information on symptoms, functional impairment, self-management burden, and burden to others.

Integrating the multiple potential measures of health status and determinants of health, including risk factors and interventions and costs, will be necessary for the ideal surveillance system to assess the status of patients living well with chronic illness and the societal impacts. The need to integrate these multiple measures has been emphasized in a recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on a framework for surveillance of cardiovascular and chronic respiratory diseases (IOM, 2011) and in reviews by others

(Fielding and Teutsch, 2011; Porter, 2010). Briefly, the conceptual framework for an ideal surveillance system to enhance living well with chronic illness incorporates the life course model that describes health status on a spectrum from illness-free to death and the ecological model of multiple determinants of health, including individual characteristics (i.e., biological makeup, health literacy and beliefs, health-related behaviors), family and community environments (i.e., social, economic, cultural, physical), and health-related interventions (i.e., public health, policy, clinical care). Measuring variations and disparities among subpopulations—for example, by age, race, gender, residence, and other factors—is a critical part of any public health surveillance system.

Surveillance of chronic diseases may also be used to monitor progress in achieving the triple aim of health care improvement: that is, to improve the patient experience, to control costs, and to improve the health of the population (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, [a]). These three aims provide further dimensions for defining relevant metrics and data sources of an enhanced surveillance system to monitor the multiple determinants and outcomes of living well with chronic illness, including the individual, the health system, and the population/community levels (Table 5-1). Moreover, these metrics and data sources reflect the multi-pronged interventions necessary for optimizing management and outcomes for patients with chronic illness, as described in the enhanced Chronic Care Model (Barr et al., 2003).

Although there is abundant evidence that the health status of patients with chronic illnesses and the quality of health care and associated costs (i.e., value) is not optimal in the United States (IOM, 2001; Porter, 2010), limited data are available on what it means at the individual level to live well (Porter, 2010; Thacker et al., 2006). Ideally, living well is defined by patients’ values and goals regarding their physical, emotional, and social functioning. However, wide variation in patients’ perspectives presents a major challenge for conducting surveillance of living well with chronic illness; the definition of living well was discussed in detail in Chapter 1. Moreover, because of barriers to access and the low value of health care in the United States, the current policy focus is largely on enhancing access and increasing value by improving quality, reducing costs by decreasing use of ineffective and/or high-cost interventions, and improving the processes of care. However, the determinants of living well with chronic illness are more complex, and these efforts alone will not adequately support patients in these circumstances.

Porter (2010) has described a health outcome hierarchy focused on health care delivery, which can be applied to provide a framework for designing a comprehensive measurement system to enhance living well with chronic illness. The principles described in this framework are as follows:

• Outcomes have multiple dimensions, which ideally include one dimension at each tier and level

—Tier 1: health status achieved or retained

o Survival

o Degree of health/recovery (e.g., quality of life, functional status)

—Tier 2: Process of recovery

o Time to recovery and return to normal activities (e.g., time to achieve functional status)

o Disutility of care process (e.g., acute complications)

—Tier 3: Sustainability of health

o Sustainability of health/recovery and nature of recurrences (e.g., frequency of exacerbations)

o Long-term consequences of therapy (e.g., care-induced illnesses)

• Outcomes must be relevant to patients and their specific illness(es) (i.e., valid)

• Multiple determinants of outcomes (e.g., disease-related, psychological, social, lifestyle) must be measured

• Measurement instruments must be standardized to provide reliability and comparability

• Measurement instruments must be sensitive to change

• Measurements must be ongoing and sustained

In addition to the measurement of health status or outcomes at the individual level, comprehensive surveillance must incorporate measures of characteristics, exposures, and processes that affect health outcomes comprising the multiple determinants of living well and their interactions at the levels of the individual, the family, and the community; health care–related interventions; and public policy. Individual health-related behaviors, including lifestyle (e.g., smoking, physical activity, diet) and self-management (e.g., medication adherence, action plans), are all influenced by patient characteristics, such as education level, health literacy, beliefs, activation, and self-efficacy. In turn, these characteristics and other exposures are partly influenced by an individual’s larger cultural, socioeconomic, and physical environments, comprised of family, work, and community. Finally, measurement of access to and utilization of health care and public health resources/interventions (e.g., structural interventions; see Katz, 2009) and coordination of care are needed to complete the assessment of factors that may contribute to patients living well with chronic illness.

Given the complexity of measuring the multiple determinants and dimensions of living well (i.e., quality of life, functional status), there is no single-best measure of living well for patients with chronic illness (Thacker

TABLE 5-1 Matrix for Surveillance for Living Well with Chronic Illness

| Health Factor and Outcomes | Examples | Patient-Reported, Individual-Level Information |

Health Care Administrative Data and Illness Registries |

Population- Based Surveys and Assessments |

| Environmental, Social, and Personal Determinants of Health | ||||

| Physical and built environment |

Air/water quality, walking paths, food deserts |

Self-report | Gco-codcd addresses | County health rankings, EPA, census |

| Social and economic factors |

Education, income, employment, social support |

Self-report (personal health record), social support, caregiver burden |

County health rankings, Dept of Education, Dcpt of Justice, census |

|

| Policy, law, and regulation |

Workplace policies on smoking, immunization; taxes on tobacco, sugar-sweetened beverages |

Self-report on awareness, enforcement of policies and laws (BRFSS] |

JCAHO data (eg., hospital smoking bans, health worker flu vaccination levels) |

State- and county-level databases of public health laws and taxes |

| Health care access, coordination, quality, and costs |

Insurance coverage, immunizations, cancer screening |

Self-report (e.g., ACOVE RAND) |

Claims data, hospital discharge data, RHIOs |

MEPS, HCAHPS |

| Health literacy, beliefs, motivations |

Health literacy, sef- efficacy, activation |

Health risk appraisal (HRA) |

||

| Health behaviors | Smoking, diet, physical activity, unsafe sex |

HRA | BRFSS. NHIS, NHANES | |

| Health Outcomes | ||||

| Social health outcomes | Relationships and functim |

Self-report (personal health record) |

National surveys | |

| Mental health outcomes | Affect, behavior, cognition, PHQ-9 |

Self-report (personal health record) |

BRFSS (limited), NHIS | |

| Physical health outcomes | ADLs, symptoms, functioning |

Self-report (personal health record) |

BRFSS (limited), NHIS | |

| lllneu-specifk outcomes | Diabetes, arlhritii. cancer, dementia |

Electronic medical record (EMR) |

Vital stats SEER, claims data(e.g., cists) |

NHIS, NHANES. BRFSS, disability from CPS |

| Primary uses of data | Improve quality and health outcomes (living well) |

Improve quality, manage costs, find "hot spots" |

Assess trends, burden, disparities (by person and placei. research |

|

NOTE: ACOVE RAND = Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders-A RAND Health Project; ADLs = activities of daily living; BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CPS = Current Population Survey; EPA = Environmental Protection Agency; HCAHPS = Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems; JCAHO = Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; MEPS = Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; RHIO = Regional Health Information Organization; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

et al., 2006), and illness-specific measures may not detect the entire patient experience (Monninkhof et al., 2004; Yeh et al., 2004). Therefore, an aggregate index of living well will consist of multiple measures from the individual, health care system, community, and policies to characterize the population (Table 5-1). However, a further challenge for surveillance of living well with chronic illness is that the majority of patients may have MCCs, which further supports the need for generic measures of health outcomes in contrast to illness-specific measures.

In summary, the best way to meet the goal of living well with chronic illness is to prevent chronic illness in the first place and, if that fails, to manage the illness to improve quality of life and prevent the development of additional chronic illness. Doing so requires a comprehensive surveillance system that includes incentives for individuals and organizations to participate in surveillance activities. The characteristics of a surveillance system to enhance living well with chronic illness are complex and integrate a number of measures of the multiple determinants and multiple dimensions of outcome most relevant to patients. Individual patient-level measures are discussed in the section below on Current Data Sources and Surveillance Methods.

USE OF SURVEILLANCE TO INFORM PUBLIC POLICY DECISIONS

Public health surveillance systems may be used to inform public policy decisions to improve the prevention and control of chronic illnesses at the individual or population level. In this section, we review how surveillance (i.e., data collection and reporting) at various levels (e.g., individual, community, health system, state, national) may be used to promote living well with chronic illness. In broad terms, these systems may be used to

• promote dissemination of evidence-based programs and policies, especially when a gap exists between research and practice;

• target interventions to areas or populations of greatest need (e.g., where health disparities are greatest); and

• evaluate the effectiveness of new or emerging interventions.

When the evidence is strong for interventions that could effectively address a gap, the surveillance effort should be focused on closing this gap by promoting the implementation of an evidence-based intervention. For example, surveillance systems have been used to demonstrate continued exposure to cigarette smoke in the workplace, the lack of advice given by physicians to quit smoking, or the slow uptake of breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer screening. Because of the complexity of the determinants of living well, effective dissemination of interventions will most often require

system-level changes at the local, state, or national level (i.e., policy, rules, regulation, culture), which are discussed in greater detail in Chapters 3 and 4.

Public health surveillance systems can also be used to identify disparities in all aspects of chronic disease prevention and control. Monitoring and reducing health disparities has been a central focus of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Healthy People efforts over the past 30 years. In Healthy People 2000, the focus was to reduce health disparities among Americans. Healthy People 2010 emphasized eliminating, not just reducing, health disparities. In Healthy People 2020, that goal was expanded even further to achieve health equity, to eliminate disparities, and to improve the health of all groups.

Surveillance efforts in chronic disease should build on the Healthy People 2020 effort by carefully monitoring health disparities, defined as “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.”

Finally, when evidence of effective interventions is not strong, surveillance systems can provide information about the effect of programs or policies in actual populations and guide future improvement efforts. Ideally, the evidence base for effective chronic disease prevention programs and policies would be developed through an explicit public health research agenda. However, evidence often evolves during the implementation of programs and policies in actual practice, using data collected in well-designed surveillance systems or population-based surveys. As more programs and policies are directed toward helping people live well with chronic illness, comprehensive surveillance systems will help evaluate their impact on populations throughout the United States.

CURRENT DATA SOURCES AND SURVEILLANCE METHODS

As described in previous sections, surveillance of living well with chronic illness is a complex phenomenon requiring multiple methods and data sources to adequately characterize and track. Overall, there are three levels of data, including patient, health system, and population. A detailed review of current population-based and health system data sources was recently conducted by IOM on the surveillance of cardiovascular and chronic respiratory diseases (IOM, 2011). In this section we provide an overview of available data sources (Table 5-2) and methods specific to the surveillance

TABLE 5-2 Selected Chronic Disease Data Sources and Surveillance Systems

| Data System | Example | Strengths | Limitations |

| Notifiable discascsa,b,c | State-based lead poisoning reporting systems | • Data are available at the local level. • Usually coupled with a public health response (e.g., lead paint removal). • Detailed information can be collected to aid in designing control programs. • Laboratory-based systems are inexpensive and effective |

• Requires participation by community-based clinicians. • Clinician-based systems have low reporting rates. • Active reporting systems are time-consuming and expensive. |

| Vital statisticsa,a,b,c | Death certificates | • Data are widely available at the local, state, and national levels. • Population-based. • Can monitor trends in age-adjusted disease rates. • Can target areas with increased mortality rates. |

• Cause of death information may be inaccurate (e.g., lack of autopsy information). • No information about risk factors. |

| Sentinel survcillanceb,c | Sentinel Event Notification System for Occupational Risks (SENSOR) | • Low-cost system to monitor selected diseases. • Usually coupled with a public health response (e.g., asbestos removal following report of mesothelioma). • Provides information on risk factors and disease severity. |

• Requires motivated reporting providers. • May not be representative. |

| Disease registriesb,c | Cancer registries | • Data are increasingly available throughout the United States. • Includes accurate tissue-based diagnoses. • Provides stage-of-diagnosis data available. |

• Systems are expensive. • Data are affected by patient out-migration from one geographic unit to another. • Risk factor information is seldom available. |

![]()

a Data are available from most local public health agencies.

b Data are available from most state departments of health.

c Data are available from many U.S. federal health agencies (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Cancer Institute, Health Care Financing Administration).

| Health surveysb,c | Behavioral risk factor surveillance telephone surveys | • Monitors trends in risk factor prevalence. • Can be used for program design and evaluation. |

• Information is based on self-reports. • May be too expensive to conduct at the local level. • May not be representative due to nonresponse (e.g., telephone surveys). |

| Administrative data collection systemsb,c | Hospital discharge systems | • Reflects regional differences on disease hospitalization rates. • Can capture cost information. • Data are readily available. • One of few sources of morbidity data. |

• Often lacks personal identifiers. • Rates may be affected by changing patterns of diagnosis based on reimbursement mechanisms. • Difficult to separate initial from recurrent hospitalizations. |

| U.S. censusaa,b,c | Poverty rates by county | • Required to calculate rates. • Important predictors of health status. • Available to all communities and readily available online. |

• Collected infrequently (every 10 years). • May undercount ertain populations (e.g., the poor, homeless persons). |

![]()

a Data are available from most local public health agencies.

b Data are available from most state departments of health.

c Data are available from many U.S. federal health agencies (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Cancer Institute, Health Care Financing Administration).

of living well with chronic illness and consider their strengths and limitations.

Patient-Level Data and Methods

Direct reports from the patient, including patient-reported outcomes (PROs) or measures of functional and cognitive performance, are the most direct measure of whether a patient is living well or not. PROs may consist of generic or illness-specific measures of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), symptoms of one’s chronic illness (Table 5-3), and measures of psychological distress. Although the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) includes a brief PRO instrument, patient-level measures are most commonly used for specific research purposes and are not routinely used for public

TABLE 5-3 Symptoms That Interfere with Living Well

|

Symptom |

Examples of Illnesses |

|

Fatigue |

• Congestive heart failure • Chronic respiratory diseases (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) • Arthritis • Depression • Sleep disorders • Posttraumatic injury/critical illness |

|

Dyspnea |

• Chronic respiratory diseases (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) • Congestive heart failure • Cardiovascular diseases • Deconditioning |

|

Pain |

• Arthritis • Cardiovascular diseases |

|

Distress |

• Depression • Anxiety • Anger • Suffering |

|

Cognitive impairment |

• Dementia • Posttraumatic injury/critical illness • Vision/hearing impairment • Cataracts • Macular degeneration • Noise-induced hearing loss |

5-4 Generic Patient Reported Outcome Measures

| Measure | Description |

| EuroQol (EQ-5D)a | Five single item measures of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. |

| Nottingham Health Profileb | Two part survey to measure subjective physical, emotional, and social aspects of health. Part I measures six dimensions of health: physical mobility, pain, social isolation, emotional reactions, energy, and sleep. Part II measures seven areas of life most affected by health status. |

| Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36)c | 36 questions with eight different sub-scores that measure physical functioning, physical role limitations, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, emotional role limitations, mental health, and two composite scores: physical component and mental component score. |

| SF-12 Health Surveyd | Shorter version of SF-36, measuring functional health being and well-being from patient’s point of view, using 12 questions. |

| SF-8 Health Surveye | Condensed version of SF-36 that relies on a single item to measure each of the eight domains of health as defined in the SF-36 Health Survey. |

aThe EuroQol Group. 1990. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16(3):199–208.

bHunt, S.M., S.P. McKenna, J. McEwen, J. Williams, and E. Papp. 1981. The Nottingham Health Profile: Subjective health status and medical consultations. Social Science and Medicine, Part A, Medical Sociology 15(3 Part 1):221–229.

cWare, J.E., Jr., and C.D. Sherbourne. 1992. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30(6):473–483.

dWare, J.E., Jr., M. Kosinski, and S.D. Keller. 1996. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 34(3):220–233.

eWare, J.E., Jr., M. Kosinski, J.E. Dewey, and B. Gandek. 2001. How to Score and Interpret Single-Item Health Measures: A Manual for Users of the SF-8 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated.

health surveillance. Moreover, functional performance may be assessed with observer-assessed physical measurements (e.g., short physical performance battery, 6-minute walk), and cognitive performance may be assessed with standardized instruments (e.g., Mini-Mental State Exam).

Generic and disease-specific PRO measures of HRQoL (Tables 5-4 and 5-5) and other outcomes related to chronic disease were developed and began to be used in the research environment in the 1980s (Fries et al., 1980; Meenan et al., 1980; Stewart et al., 1988). PROs, such as the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) used in arthritis, have been shown to predict morbidity and mortality in some chronic diseases as effectively as laboratory,

TABLE 5-5 Illness-Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

| Measure | Description |

| Adult Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ)a | 32 items that produce 4 dimension scores relating to activity limitations, symptoms, emotional function, and environmental exposure. |

| Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS)b | 9 scales that measure physical, psychological, and social health status outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients. |

| Arthritis Self-efficacy Scale (ASES)c | 20-item scale across 3 domains, including coping with pain, function and other symptoms to measure self-efficacy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. |

| Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ)d | 20 items that produce 4 dimension scores relating to dyspnea, fatigue, emotional functioning, and mastery to measure health-related quality of life in patients with difficulty breathing. |

| EXAcerbations of Chronic Pulmonary Disease Tool (EXACT)e | 14-item daily diary to evaluate frequency, severity and duration of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic bronchitis. |

| Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)f | Five-dimension comprehensive outcome measure that assesses patient outcomes in four domains: disability, discomfort and pain, drug side-effects (toxicity), and dollar costs, developed for those with arthritis but now used more generically. |

| Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ)g | 19 items across 5 dimensions of coronary artery disease: anginal stability and frequency, physical limitation, treatment satisfaction, quality of life. |

| St. George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)h | 50-item, 76 weighted responses divided into 3 components: symptoms, activity, and impacts to quantify health-related health status in patients with chronic airflow limitation. |

| Western Ontario McMasters University Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)i | 24 items across 3 subscales that assess pain, stiffness and physical function in patients with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis (OA). |

aJuniper, E.F., G.H. Guyatt, P.J. Ferrie, and L.E. Griffith. 1993. Measuring quality of life in asthma. American Review of Respiratory Disease 147(4):832–838.

bMeenan, R.F., P.M. Gertman, and J.H. Mason. 1980. Measuring health status in arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 23(2):146–152.

cLorig, K., R.L. Chastain, E. Ung, S. Shoor, and H.R. Holman. 1989. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 32(1):37–44.

dGuyatt, G.H., L.B. Berman, M. Townsend, S.O. Pugsley, and L.W. Chambers. 1987. A measure of quality of life for clinical trials in chronic lung disease. Thorax 42(10):773–778.

eLeidy, N.K., T.K. Wilcox, P.W. Jones, L. Murray, R. Winnette, K. Howard, J. Petrillo, J. Powers, S. Sethi, and EXACT-PRO Study Group. 2010. Development of the EXAcerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Tool(EXACT): A Patient-Reported Outcome(PRO) measure. Value Health 13(8):965–975.

fFries, J.F., P. Spitz, R.G. Kraines, and H.R. Holman. 1980. Measurement of patient outcomes in arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 23(2):137–145.

gSpertus, J.A., J.A. Winder, T.A. Dewhurst, R.A. Deyo, J. Prodzinski, M. McDonell, and S.D. Fihn. 1995. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: A new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 25(2):333–341.

hJones, P.W., F.H. Quirk, C.M. Baveystock, and P. Littlejohns. 1992. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. The American Review of Respiratory Disease 145(6):1321–1327.

iBellamy, N., W.W. Buchanan, C.H. Goldsmith, J. Campbell, and L.W. Stitt. 1988. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Journal of Rheumatology 15(12):1833–1840.

radiographic, and performance-based measures of physical function in longitudinal observational studies (Pincus and Sokka, 2003; Wolfe and Pincus, 1999). In clinical trials, PROs have been demonstrated to have a higher relative efficiency when analyzing differences between active versus placebo treatments in patients with chronic illness (Strand et al., 1999, 2005; Tugwell et al., 2000). The SF-36v2, SF-12v2, and SF-8 health surveys are the most widely used generic PRO measures for assessing eight health domains (Ware et al., 1994, 1997, 2001). Psychometrically based physical component summary (PCS) scores and mental component summary (MCS) scores can be derived from each survey. In addition to the generic PRO measures, there are many disease-specific PRO measures. These commonly used generic and disease-specific PROs have been demonstrated to be reliable, valid, and sensitive to change—properties that are essential for all patient-level measures, whether they are self-reported or performance-based.

The common measures discussed above were developed using classical test theory. The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Roadmap network project, is intended to improve the reliability, validity, and precision of PROs using modern measurement techniques, including item-response theory and computerized adaptive testing. The measures being developed from the initiative may be very useful for surveillance of patient-level outcomes (see the section “The Use of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Surveillance Systems”). Much of the research focus has been on illness-specific instruments because of enhanced responsiveness, but for MCCs and public health, more generic instruments that are cross-cutting and characterize living well are needed. PROMIS measures are designed to be cross-cutting for individuals with any illness (or none).

Although self-reported measures of functional performance may be most feasible for surveillance, the validity of these measures for assessing physical performance is limited (Reuben et al., 1995). Performance-based measures of physical function are often measured for research purposes and in clinical settings; however, their use in population-based surveillance has been largely limited to cross-sectional surveys, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a cross-sectional, population-based survey (Kuo et al., 2006). Two measures of physical performance that have been used in NHANES are peak leg power and usual gait speed (Kuo et al., 2006), which are associated with late-life disability. The short physical performance battery (SPPB) and the composite of standing balance, walking speed, and ability to rise from a chair are predictors of future disability among the elderly (Guralnik et al., 1995). The Senior Fitness Test has been developed to assess physical performance in older adults across a wide range of age groups and abilities (Rikli and Jones, 2001). The items in the test reflect a cross-section of the major fitness components associated

with independent functioning in later years. The Senior Fitness Test includes measures of upper and lower body strength, aerobic endurance, upper and lower body flexibility, gait speed, and agility/dynamic balance.

Surveillance of cognitive performance is uncommon, but it has been included in the NHANES using the Mini-Mental State Examination (Obisesan et al., 2008). This instrument consists of six orientation, six recall, and five attention items. For NHANES respondents over age 70, these items have been associated with hypertension and uncontrolled hypertension (Obisesan et al., 2008).

In addition to PROs and measures of functional and cognitive performance, other patient-level measures with potential relevance to living well may include patient reports of quality of care and employee surveys. RAND health researchers developed a set of quality indicators that reflect the most comprehensive examination of the quality of medical care provided to vulnerable older Americans, the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) indicators (Chodosh et al., 2004). In it, 22 illnesses that account for the majority of health care received by older adults were identified; these included illnesses, syndromes, physiological impairments, and clinical situations. After review by expert panels and the American College of Physicians Task Force on Aging, 236 quality indicators were accepted. These indicators factor in four stages of the health care process: prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. ACOVE researchers found that patients who receive better care are more likely to be alive 3 years later than those who received poor care. Patients with MCCs were the least likely to receive adequate care.

Surveillance of both employee workplace attendance and productivity may provide an indicator of functional impact among workers with chronic illnesses. For example, “presenteeism is defined as ‘lost productivity that occurs when employees come to work but perform below par due to any kind of illness.’ While costs associated with absenteeism of employees have been studied for some time, only recently have costs of presenteeism been studied” (Levin-Epstein, 2005).

Health-System Data and Methods

Although not direct measures of living well, access to and quality of health care services partly influence health outcomes among patients with chronic illnesses and are frequently used as process measures to evaluate how well health systems address patient care needs. Health insurance status and health care utilization claims data are often used as measures to infer access to and quality of health care services. For example, examination of variations in hospitalization rates for selected chronic diseases, termed ambulatory care sensitive conditions (e.g., congestive heart failure, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], diabetes), has demonstrated that loss of Medicaid coverage is associated with higher hospitalization rates for these conditions, suggesting suboptimal disease control because of inadequate access to primary care services (Bindman et al., 2008). Disparities in access to health care associated with poor health outcomes has also been suggested by higher hospitalization rates (Jackson et al., 2011) and mortality rates (Abrams et al., 2011) among rural residents with COPD using state and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) data on hospitalizations, respectively.

On a national level, measurement of performance in health care is relatively new and started with U.S. hospitals in 1998 as a condition of accreditation (Chassin et al., 2010). It has expanded to include measures of outpatient performance in 2007, termed the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (Metersky, 2009). These measurements and reporting initiatives, termed pay-for-performance or value-based purchasing, are part of the evolving transformation of the health care system in the United States with a growing emphasis on quality of care at lower costs (Berwick, 2011; Conway and Clancy, 2009; Lindenauer et al., 2007). Moreover, the electronic health record (EHR), discussed in greater detail in the next section, will provide the foundation for enhanced data collection and reporting with the goal of “meaningful use” to improve quality of care and health outcomes (Classen and Bates, 2011; Maxson et al., 2010). A limitation of these data sources and measures is that performance on process measures does not reliably predict health outcomes that are relevant to living well with chronic illness (Chassin et al., 2010; Porter, 2010).

Administrative health care claims data from a number of sources, including Medicare and Medicaid (Schneider et al., 2009; The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, [a]), the VA (Abrams et al., 2011), and hospital consortia (Lindenauer et al., 2006), are frequently used to assess the quality and cost of health care services. Moreover, with the growing recognition of the need for data to evaluate health system performance and public health policy, a number of states are developing all-payer claims databases (Love et al., 2010).

In addition to health care claims data, patient registries provide a method for directly measuring whether patients are living well. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has defined a patient registry as “an organized system that uses observational study methods to collect uniform data (clinical and other) to evaluate specified outcomes for a population defined by a particular illness, condition, or exposure and that serves predetermined scientific, clinical or policy purpose(s).” There are a number of different types of patient registries, such as illness, treatment, device, and after-care registries. The use of registries and health care services claims

data for chronic disease surveillance was reviewed in greater detail in a recent IOM report (2011).

Population-Based Data and Methods

Population-based data and information about chronic diseases, including measures of living well, are available from a number of sources (Table 5-2). The methods used to support these systems vary, depending on the type of data system and the population it covers. In addition, data from these systems, such as illness occurrence and health-related quality of life, may be used to derive estimates of illness burden and construct cost-effectiveness analyses—for example, disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

The most robust surveillance systems are census-based, collecting information from the entire population and including vital statistics (birth, death) records similar to those of the U.S. Census Bureau. These systems could provide precise estimates of occurrence of chronic illnesses or other health determinants since they include the entire population, but they would be expensive to support.

Population-based samples are used to conduct surveys to measure self-reported factors related to living well with chronic illness (e.g., quality of life) at the national level and, since 1984, at the state level as part of the BRFSS (Mokdad and Remington, 2010). Methods also exist to survey people in person, in order to measure chronic illness occurrence and its impacts on functional and cognitive performance at the national level (e.g., NHANES) and in some states (e.g., Survey of Health of Wisconsin). Examples of these systems include population-based surveys (e.g., the BRFSS, the National Health Interview Survey, NHANES, state and local surveys) to estimate the prevalence of disability (Brault et al., 2009) or quality of life (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]: BRFSS healthy days core module HRQoL-4) (four questions), activity limitations module (five questions), and healthy days symptoms module (five questions) (http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/hrqol14_measure.htm). A number of systems use administrative data:

• Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS): patient survey of hospital care experience

• Prevention Quality Indicators: www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/pqi_overview.htm

• Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/

A number of organizations have developed web-based systems to access population-based data either to conduct primary data analysis (Friedman

and Parish, 2006) or to retrieve summary reports. Examples of such systems include

• Community Health Status Indicators: www.communityhealth.hhs.gov

• County Health Rankings: www.countyhealthrankings.org

• The Community Health Data Initiative: www.hhs.gov/open/datasets/communityhealthdata.html

• The Health Indicators Warehouse: http://www.healthindicators.gov/

• The American Community Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau

Population-based data on illness occurrence and health-related quality of life may be used for estimating DALYs (Grosse et al., 2009) for use in cost-effectiveness analyses. However, because DALYs are not estimated using direct measures of disability, the validity of this estimate is suspect (Grosse et al., 2009).

Limitations/Data Gaps

Current surveillance of chronic diseases emphasizes risk factors and disease occurrence, and few longitudinal data are obtained on PROs or functional and cognitive performance at the level of health care systems or local, state, and national populations. Despite advances in public health surveillance and health information systems (e.g., electronic health records), few communities have comprehensive surveillance systems to measure chronic diseases and related health risk factors and quality of life. Few health care systems routinely collect information on health-related quality of life as part of the electronic medical record. And, because available process measures do not reliably predict health outcomes, they have limited usefulness for measuring and rewarding performance relevant to living well at the health system or community level.

Data collection is further complicated because of the many potential confounding variables (e.g., age, gender, geography, race/ethnicity, number of comorbid illnesses, health literacy, social support) that may influence living well and are needed to appropriately analyze and interpret results. Moreover, although many people have MCCs, this factor has received limited attention. Finally, rare diseases cannot be accurately measured in population-based surveys. Overcoming these limitations for conducting surveillance for living well with chronic illness is further complicated by the dramatically increasing costs of collecting this information at the population level, as fewer homes have landline telephones and telephone surveys

response rates continue to fall. Future systems should be able to capture this information within the health care system and build up to provide information on community, state, and national health risk behavior, chronic disease, and quality of life.

PUBLIC HEALTH SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM INTEGRATION

One of the biggest weaknesses of the current surveillance systems for chronic illness is the lack of integration between information collected at the patient, health system, and population levels. Detailed information may be collected from patients about chronic diseases, risk factors, and quality of life, but it is rarely captured in comprehensive health system databases. Health system information, primarily derived from administrative billing systems, is rarely used to assess chronic disease control at population levels. Finally, information collected at the population level, ranging from detailed census information to characteristics of the built environment, is rarely included in health system information systems.

Another limitation is the lack of information about health outcomes of individual patients over time so that transitions in health status can be monitored. Most available data are on process outcomes rather than health outcomes, and longitudinal data are rarely available. In addition, despite advances in health information technology, these information systems are not well integrated, and the number and variety of systems are likely to increase with advances in electronic data interchange and integration. These changes will also heighten the importance of patient privacy, data confidentiality, and system security. Finally, the value of health care and other interventions to improve health outcomes can be determined only by examining costs and health outcomes, but few data sources include costs (Rosen and Cutler, 2009).

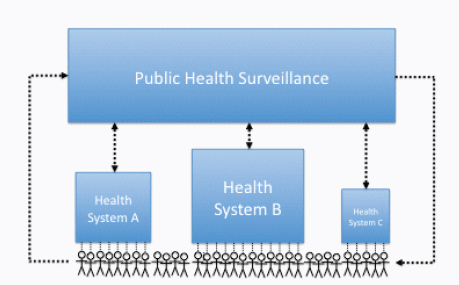

It is technically feasible to integrate existing surveillance systems along the entire continuum of prevention, starting with patient-reported information, to improving the performance of health care systems, to monitoring risk factor and outcome trends over time at the community, state, or national level (i.e., population level). This integration at the level of health care system, with examples, has been extensively reviewed in a series of Institute of Medicine workshops on “The Learning Healthcare System” (IOM, 2007). Figure 5-1 shows how health information can be collected and potentially integrated at three different levels. This section describes these three levels of information systems, provides examples of existing systems, and describes barriers and opportunities for improving systems in the future.

FIGURE 5-1 Integration of health system and public health surveillance systems. SOURCE: Committee on Living Well with Chronic Disease: Public Health Action to Reduce Disability and Improve Functioning and Quality of Life.

Patient-Level Surveillance Systems

Surveillance systems of chronic illnesses may be used to evaluate the effectiveness of patient care and public health interventions and should include outcome information relevant to living well collected directly from patients. However, although the patient-reported perspective of living well is the “gold standard” (e.g., living well or patient-reported health outcomes), this remains a major gap in surveillance for chronic illnesses (Porter, 2010). This is a rapidly growing area of research and, with the growing use of electronic medical records (EMRs), an emerging opportunity for chronic disease surveillance.

An example of the relevance and feasibility of self-reported ratings of living well was provided by Strine and colleagues (2008), who analyzed data from a national sample in excess of 340,000 noninstitutionalized adults using the BRFSS and found that even a single question rating life satisfaction, a surrogate for living well, was strongly associated with unhealthy lifestyles, decreased health status, disability, and chronic illness. However, this measure has not been used to assess interventions among patients with chronic illnesses. Moreover, although measures of self-reported health-related quality of life are the major outcomes in research trials of clinical

and public health interventions, they are not often used in routine clinical care or related surveillance systems. However, widespread implementation of electronic medical records (discussed below) may provide the opportunity to conduct widespread surveillance of patient-reported outcomes.

Finally, recent advances in the application of the genetics and molecular biology to patient illnesses are likely to change the nature and interpretation of surveillance over the next few years. This has sometimes been called “personalized medicine” (Offit, 2011), leading to changes in illness risk, classification, clinical behavior, and outcomes. Some implications include

• Altered classification of diseases and conditions according to molecular or genetic characteristics, such as subgroups of breast cancer with the HER-2-neu marker.

• Differential treatment approaches based on molecular markers, such as levels of P450 enzymes, leading to varied medication applications.

• Altered risk of incident diseases based on molecular markers. A large number of genetic variants have now been related to disease risk and occurrence. Although these altered risks for chronic diseases have not been large, such risks may be large enough to change screening practices.

Health Care System–Level Surveillance Systems

Information about chronic illness care and outcomes is collected by health systems as part of routine patient care. These data systems include descriptive information about patient demographics, residence, and insurance status. Using patient addresses, area-level information can be appended to patient records, such as median household income, census tract rates of poverty or crime, and characteristics of the built environment. Billing information is available on most patients (e.g., fee-for-service) on procedures, diagnoses, and hospitalization.

Health care organizations have used health information systems to improve processes of care and to reduce costs. Most of these systems have focused on measuring quality of health care using process measures, but relatively few routinely incorporate measures of health outcomes. These systems hold promise for improving health outcomes, as long as there is a strong link between the process measure and the expected health outcome. Berwick and others have described how improving the U.S. health care system requires simultaneous pursuit of three aims: improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care (Berwick et al., 2008).

However, those working on the Triple Aim projects may focus on the two more concrete goals of improving the experience of health care and reducing per capita costs of health care and less on the aim of improving population health (Kindig, 2011). Kindig states that “the reality is that even major progress in these two areas over the next decade will not help us achieve our goals related to healthy life expectancy and disparity reduction.”

Since the late 1990s—and partly as a result of two IOM reports, which describe the frequency of errors and mortality associated with hospitalization (To Err Is Human) and gaps in quality of care in the U.S. health care system (Crossing the Quality Chasm)—there has been increasing attention on measuring health care safety and quality, which is linked to hospital accreditation and reimbursement (Chassin et al., 2010) (see below). Moreover, these surveillance activities have resulted in nationwide initiatives to enhance the capacity of health systems to use the data and drive performance improvement (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, [a]). However, these activities have largely focused on improving safety and outcomes associated with acute care rather than improving longer-term outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses.

According to Porter, outcome measurement is perhaps the single most powerful tool that could be used to improve the quality of care among persons with chronic illness. As the true measures of quality in chronic illness care, it is necessary to measure, report, and compare specific and multidimensional outcomes. Understanding the outcomes achieved is also critical to ensuring that cost reduction is value enhancing (Porter, 2010). In his review, Porter suggests that although outcome measurement in the health care system is uncommon, there are examples that have proven practical and economically feasible. Moreover, accepted risk adjustment has been developed and implemented and although measurement initially revealed major variation in outcomes in each case over time, striking outcome improvement and narrowing of variation across providers were the result (Porter, 2010).

Despite consensus of the importance of measuring health outcomes in efforts to help patients live better with chronic illness, there is little consensus about what constitutes an optimal outcome and the distinctions among care processes, biological indicators, and outcomes remain unclear in practice (Porter, 2010). Currently used outcome measures tend to focus on the immediate results of particular interventions rather than the overall success of the full care cycle longitudinally for medical diseases or primary and preventive care. In addition, measured outcomes often fail to capture dimensions that are highly important to living well with chronic illness (Porter, 2010).

According to Porter, generalized outcomes, such as overall hospital infection

rates, mortality rates, medication errors, or surgical complications, are too broad to permit proper evaluation of a provider’s care in a way that is relevant to patients. Porter states that these generalized outcomes also obscure the causal connections between specific care processes and outcomes, since results are heavily influenced by many different processes (Porter, 2010). However, these system-level measures may be valuable for guiding organizational or public health interventions and future research (Conway and Clancy, 2009; Dougherty and Conway, 2008).

In addition to measuring health outcomes to drive performance improvement, analyzing health care costs has demonstrated wide geographic variations in risk-adjusted costs, which are not consistently associated with health outcomes (The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, [a]). These observations have partly contributed to recent health reform policies and regulations at the national and state levels to minimize variation in costs in an attempt to control rising health care costs.

Population-Based Surveillance Systems

Public health surveillance systems are an essential complement to patient- and health system–based information systems. These population-based health information systems have evolved over the past 50 years, broadening the scope from infectious to chronic diseases. Traditional surveillance systems that focused on infectious diseases have been expanded to include chronic diseases and chronic disease risk factors. CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries now supports central cancer registries in 45 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Pacific Island jurisdictions, representing 96 percent of the U.S. population. Together with the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, cancer incidence data are available for the entire U.S. population.

During the 1980s, CDC established surveillance systems to monitor trends in risk factors for chronic diseases among adults (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) and children (Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, or YRBSS). These state-based systems for the first time provided information for state and selected local health departments for program planning and evaluation. The colored maps showing the increasing rates of obesity in every state during the past several decades have been seen by countless professionals, students, and members of the public.

In addition, there has been a growing awareness of the impact the built environment has on people’s physical and mental health. Therefore, several interesting new surveillance methodologies have been developed that aim to monitor the health of individuals in the context of the communities in which they live, involving a complex interaction of health determinants,

health outcomes, physical measurements, biological samples, policies, and the built environment (Nieto et al., 2010).

Public health surveillance systems are used to assess the causes and consequences of chronic illnesses, including measuring the burden, monitoring changes over time, and evaluating the effectiveness of broad-based interventions. These systems are generally developed and operated by governmental public health agencies at the local, state, or national level and vary from a simple system collecting data from a single source, to electronic systems that receive data from many sources in multiple formats, to complex population-based surveys. Accordingly, these systems address a range of public health needs:

a. “guide immediate action for cases of public health importance;

b. measure the burden of a disease (or other health-related event), including changes in related factors, the identification of populations at high risk, and the identification of new or emerging health concerns;

c. monitor trends in the burden of a disease (or other health-related event), including the detection of epidemics (outbreaks) and pandemics;

d. guide the planning, implementation, and evaluation of programs to prevent and control disease, injury, or adverse exposure;

e. monitor adverse effects of interventions (e.g., the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and drugs);

f. evaluate public policy;

g. detect changes in health practices and the effects of these changes;

h. prioritize the allocation of health resources;

i. describe the clinical course of disease; and j. provide a basis for epidemiological research” (German et al., 2001).

Summary

Multidimensional surveillance of risk factors and health outcomes data at the patient, health organization, and population levels is essential for informing decisions on priorities and interventions to enhance living well with chronic illness at the level of patients, health organizations, and communities. However, many barriers continue to exist that prevent optimal integration and use of these data for program planning and evaluation.

Future chronic disease surveillance systems should integrate information from patient-, health system–, and population-based surveillance systems. The County Health Rankings (www.countyhealthrankings.org) is an example of an integrated system for surveillance of the overall health of a

community that could be adapted for measuring living well with chronic illness. For example, rather than relying on estimates of quality of life from telephone surveys, health outcomes for communities could integrate information about quality of life from patient and health system databases.

FUTURE DATA SOURCES, METHODS,

AND RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

The need for improved chronic disease surveillance systems is great, given the increasing demands for better patient experiences, lower costs, and improved population health outcomes. Future decisions about these systems will be driven by multiple factors, including the burden of illnesses and effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of interventions, along with cost-benefit considerations (Glasgow et al., 1999). This section describes methods, data sources, and research needed to meet this increasing demand in the future.

Although many environmental, social, and health care factors contribute to health outcomes for persons with chronic illnesses, the current health care reform initiatives at the federal level are largely targeting health care access and quality. In addition, these initiatives include a number of policies and programs intended to enhance surveillance for chronic disease and enhance coordination of care. However, given the many determinants of health, the focus on enhancing access to care and transforming delivery of health care alone will be insufficient for helping persons with chronic illness to live well.

Measurement and incentives will drive health system change to improve chronic illness care. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act (Blumenthal, 2010) provides incentives to facilitate the adoption of health information technology/electronic medical records, which will provide the foundation for surveillance data of health care and decision support. There are several provisions in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to promote chronic disease surveillance. A provision of the ACA states that “any federally conducted or supported health care or public health program, activity or survey collects and reports, to the extent practicable data on … disability status” and data collection standards have been developed to address this mandate (http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=208). Group health plans will be required to report annually to the HHS on their benefits and reimbursement structures that improve quality of care and health outcomes for individuals with chronic health illnesses (http://www.scribd.com/doc/57950324/Health-Care-Shalls-in-the-Affordable-Care-Act). Tax-exempt hospitals will be required to conduct community health needs assessments every 3 years. Although this provision acknowledges the relevance of integrating data

from the health care system and the community to drive performance improvement, no details are provided about what should be measured.

Recent developments in health information technology provide numerous avenues for the collection of individual-level health information that is relevant to living well with chronic illness. However, in using such data, consideration is needed to determine the extent to which the data are using measures that are reliable, valid (i.e., internally and externally), and responsive to change. In subsequent sections, we review potential methods and data sources for future surveillance to enhance living well, and research needs to address current gaps in knowledge relevant to surveillance for chronic illnesses.

The Use of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Surveillance Systems

PRO measures are considered essential for monitoring outcomes and quality of life in individuals with chronic illness. Recent years have seen a number of advances in the science of PROs, particularly by the PROMIS group, which funded the development of item banks as well as short forms and computer-adaptive tests to measure a range of PROS. Health domains for PROMIS were built on the World Health Organization framework of physical, mental, and social health (Cella et al., 2007). Domain definitions were created for physical function, fatigue, pain, emotional distress (including anxiety, depression, and anger), social health (including social function and social support), and global health. PROMIS instruments available as of June 2011 are listed in Table 5-6.

PROMIS instruments were validated and calibrated in samples from the U.S. general population and multiple illness populations, including individuals with arthritis, congestive heart failure, COPD, cancer, and other illnesses. The instruments are designed to measure feelings, functions, and perceptions applicable to a range of chronic illnesses, enabling efficient and interpretable clinical research and clinical practice application of patient-reported outcomes. The instruments have been validated against legacy illness-specific instruments.

New Modes of Data Collection

There is an increasing number of modes for the collection of health information, including patient-reported outcomes, that may be used for surveillance efforts in the future. For example, many employers use health risk appraisals (HRAs) as feedback tools for their employees to improve their health. Although these assessments are meant to be tools to help individuals improve their health status and thus tend to focus on health behavior and preventive health care utilization, it could be particularly

TABLE 5-6 Available PROMIS Instruments

|

Domain |

Bank |

Short Forms |

|

|

Emotional distress–anger |

29 |

8 |

|

|

Emotional distress–anxiety |

29 |

4, 6, 7, 8 |

|

|

Emotional distress–depression |

28 |

4, 6, 8a, 8b |

|

|

Applied cognition–abilities |

33 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

|

Applied cognition–general concerns |

34 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

|

Psychosocial illness impact–positive |

39 |

4, 8 |

|

|

Psychosocial illness impact–negative |

32 |

4, 8 |

|

|

Fatigue |

95 |

4, 6, 7, 8 |

|

|

Pain–behavior |

39 |

7 |

|

|

Pain–interference |

41 |

4, 6a, 6b, 8 |

|

|

Pain intensity |

3 |

||

|

Physical function |

124 |

4, 6, 8, 10, 20 |

|

|

Mobility |

|||

|

Upper extremity |

|||

|

Physical function for samples with mobility aid users |

114 |

12 |

|

|

Sleep disturbance |

27 |

4, 6, 8a, 8b |

|

|

Sleep-related impairment |

16 |

8 |

|

|

Sexual function: global satisfaction with sex life and 10 other subscales |

7 |

||

|

Satisfaction with participation in discretionary social activities |

12 |

7 |

|

|

Satisfaction with participation in social roles |

14 |

4, 6, 7, 8 |

|

|

Satisfaction with social roles and activities |

44 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

|

Ability to participate in social roles and activities |

35 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

|

Companionship |

6 |

4, 6 |

|

|

Informational support |

10 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

|

Emotional support |

16 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

|

Instrumental support |

11 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

|

Social isolation |

14 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

|

Peer relationships |

|||

|

Asthma impact |

|||

|

Global health |

10 |

||

SOURCE: PROMIS Assessment Center. Instruments Available for Use. http://assessmentcenter.net/documents/InstrumentLibrary.pdf.

useful for individuals with chronic illness to track health outcomes, such as PROs, over time.

Online personal health records (PHRs), like the Health Vault by Microsoft, may also eventually provide data for surveillance of living well with chronic illness. Such tools allow individuals to record and track their own health information online. Some systems have the ability to link with a health care system’s electronic health record, and so adoption of EHRs by health care systems is important to the usefulness of such tools, as is the interoperability between the PHR and health care system EHR (Archer et al., 2011). A further limitation is that not all PHRs include the type of outcomes that are relevant to living well with chronic illness. In particular, valid and reliable PRO measures are not widely available in these systems, although there may be value to a person living with a chronic illness in tracking an outcome like pain or fatigue. Incorporation of such measures into PHRs could help increase their usefulness to surveillance efforts as well. However, the use of PHRs requires long-term use and considerable effort on the part of the health consumer. More research is needed to identify ways to optimize the usefulness of PHRs for individuals and identify methods to motivate and increase their use (Archer et al., 2011).

Registries have long been used as a method for studying diseases. Traditional registries (e.g., cancer registries) usually involve information submitted by the health care provider. Although such registries are used for surveillance (the SEER registry being a prime example), they rarely assess the patient-reported outcomes that are relevant to living well with chronic illness. Often, the patient has not consented to follow-up contact; conducting surveillance that involves recontacting patients therefore often requires several costly steps, such as requesting permission from the health care provider. However, a number of registries are emerging in which individuals themselves volunteer for the registry, expressing their willingness to participate in health research. Examples include two state-based registries—the Illinois Women’s Health Registry and the Kentucky Women’s Health Registry—and a disease-specific registry, the Susan Love Foundation’s Army of Women, a registry of breast cancer survivors and women without breast cancer who are willing to participate in research related to breast cancer. Also, for some registries, information is submitted by health care providers rather than the participants themselves (e.g., cancer registries). Registries could be used for surveillance efforts related to living well with chronic illness, but attention needs to be paid to assessing selection bias in who enrolls in registries.

Online networks for individuals with chronic illness may also provide opportunities for surveillance. For example, networks, such as Patients Like Me and Cure Together, have as part of their goal information gathering and sharing that can help patients understand their illness course and effective

treatments. Patients Like Me has a membership of 114,953 patients. They routinely collect patient-reported outcomes on their website, although participation in this data collection is voluntary. It is a for-profit organization whose business model includes selling the patient information to clients like pharmaceutical companies. The network started by serving primarily the ALS community. It conducted an observational study with matched controls on the use of lithium among their members with ALS. The study found the same result as subsequent trials, that lithium was of no benefit in slowing the progression of this illness (Wicks et al., 2011). Cure Together has approximately 25,000 members. It asks members to provide data on symptoms, treatments they have tried, and effectiveness of treatments and then share the results online with other members. Another example is registries of patients with chronic lung diseases (http://www.alpha1registry.org/index.html). Such networks could be tapped for surveillance efforts in the future, but consideration of selection bias is still necessary. Furthermore, it is unclear to what extent these networks use validated assessment tools that are reliable and sensitive to change in their data gathering, which would be important for surveillance measures (Thacker et al., 2006).

With the increasing adoption as well as incentives and support for adoption of electronic medical records, future surveillance methods may be able to utilize this information to monitor whether patients are living well. One of the components of meaningful use is submitting clinical quality and other measures, but this does not currently include measures of living well (Classen and Bates, 2011). Although it is common to use medical care records to monitor quality of care, the potential exists to use these data to track outcomes as well. However, available research evidence does not include patient-level outcomes for assessing the effectiveness of EMRs, and only recently has cross-sectional evidence suggested that the use of EMRs is associated with improvements in standards of care processes and intermediate outcomes compared with paper records for patients with diabetes (Cebul et al., 2011). If brief patient-reported outcome measures are incorporated into the EMR for patients with chronic illnesses, these data could be used to provide longitudinal information on quality of life indicators of importance to this population, extending current systems that primarily monitor statistics related to illness mortality. While the entire nation does not have access to electronic medical records at this time, there is still widespread availability of EMR covering large segments of the population. The use and availability of EMR will continue to expand, which supports the incremental approach to enhanced chronic disease surveillance. The PROMIS measures are ideal for such a system because they are reliable and validated, brief, and applicable across a range of chronic diseases.

Syndromic surveillance refers to the detection of outbreaks or disease trends using automated surveillance of pre-diagnostic data, including, for

example, sales of over-the-counter medications or emergency room visits. Movement toward electronic medical records may make such surveillance feasible with medical records, but innovative applications of more population-based data have also been explored. Data mining of information collected by search engines or in either general or disease-specific online social networks may be more sensitive to such detection methods. However, one limitation of this approach is that such methods are more sensitive to short-term changes (e.g., influenza epidemics; see Signorini et al., 2011). In addition, people with chronic illness are less likely to have Internet access than others, raising the possibility of selection bias in who provides information. However, people with chronic illnesses who go online are more likely to seek out others with similar health concerns than are those without chronic illness (Fox, 2011), indicating that this may be a fruitful area for surveillance, as more people with chronic illness obtain access to the Internet.

Research on Measurement of Chronic Disease

Although the need for surveillance is a well-established function of public health, surveillance of chronic illness to enhance living well is complex and presents a number of challenges that will require further investigation at the individual, health organization, and population levels. Moreover, the effectiveness of potential future methods and data sources for surveillance to drive improvement will need to be determined.

Individual Level

The measurement of patient-reported outcomes continues to be an active area of investigation (as previously described for PROMIS), and much of the research focus has been on reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change. For example, there is limited evidence on sources of variation of HRQoL, including gender (Cherepanov et al., 2010), season (Jia and Lubetkin, 2009), and MCCs (Chen et al., 2011). Further research is needed to determine other sources of variation (e.g., health literacy, socioeconomic factors). Moreover, the reliability of surveillance of HRQoL remains controversial, in need of further research (Avendano et al., 2009; Salomon et al., 2009). For specific illnesses, further qualitative research to obtain the patient’s perspective (e.g., illness intrusiveness, regrets about treatment decisions) may be needed to strengthen the validity of measures of patient-reported outcomes for measuring living well. In addition to patient-reported outcomes, little is known about the feasibility and potential usefulness of objective, longitudinal measures of functional and cognitive capacity for surveillance. Finally, in the context of health care reform and concern about costs, the burden and costs versus benefits of surveillance of patient-