Alice Abreu,1Lisa M. Frehill,2Kathrin K. Zippel3

Our work focuses on the concepts and measurement tools of workforce segregation at the macro, middle, and micro levels of analysis. At the macro level, we consider the labor-force at the national or institutional level. The middle level of analysis pushes us to attend to how the institutional processes of qualification, training, recruitment and retention within scientific careers are impacted by the social institution of gender. Finally, at the micro level, we grapple with the ongoing debates around the concept of “choice.” That is, to what extent do differences in occupational structures and careers reflect choices made by active agents, and to what extent are choices constrained by gender as a social institution? How do individuals navigate through scientific careers within these larger contexts?

Macro Level

At the macro level, the observed differences in the distributions of women and men into different occupations reflect the outcomes of a wide range of social forces, operating at the macro, middle, and micro levels, some of which may have intentionally sought to disadvantage women, while others result in different treatment of women and men, patterned by gender, as unintended consequences. As such, segregation is simply a description of an existing set of relations. The intentionality of the social forces that lead to segregation are a matter of much debate, to which we are encouraged to consider once we engage in the comparative analyses associated with the metrics.

To what extent is workforce segregation an intentional outcome? This is a critical issue. In the United States, the English word “segregation” often calls forth images of residential segregation that, in U.S. history was, indeed, intentional and enforced by both law and custom. Such an issue may not be present in discourse about workforce segregation in other countries where the term does not carry this historical “baggage.” The point is still salient, though, regardless of context. In some contexts, women’s work and men’s work are, or have been, explicitly segregated. Again, while this may be accomplished by force of law, informal customs and practices should not be overlooked; even in advanced industrial nations, jobs like nursing are seen as “women’s work” and jobs like engineer are seen as “men’s work.” At the other end of the spectrum, though, segregation may be viewed as an unintended consequence of individuals’ choices.

__________________

1 Alice Abreu, regional coordinator, Rio+20 Initiative, International Council of Science.

2 Lisa M. Frehill, senior research analyst, Energetic Technology Center.

3 Kathrin K. Zippel, ADVANCE co-principal investigator, Northwestern University.

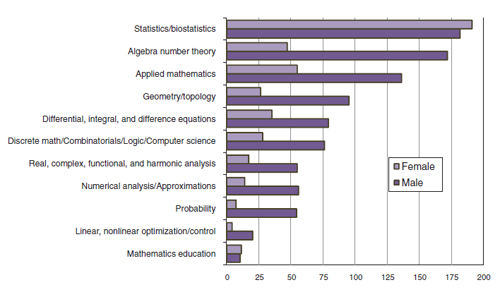

Segregation can be described along both horizontal and vertical dimensions. The horizontal dimension describes how women and men are distributed across some set of occupational fields or, in the case of educational programs, different fields of study. Figure E-4-1, for example, shows the subfields of women and men who earned doctoral degrees awarded by mathematics departments in the United States in 2008. The largest number of degrees was awarded in statistics and biostatistics, in which women accounted for 51 percent of the Ph.D. recipients. Women also accounted for just more than half (54 percent) of the doctoral degrees in mathematics education. Among the other nine fields shown in the chart, women accounted for between 12 percent (probability) and 31 percent (differential, integral, and difference equations) of the doctoral degree recipients.

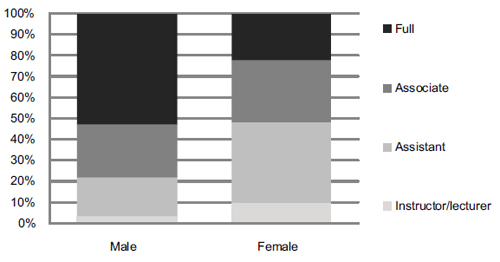

The vertical dimension, then, provides an understanding of segregation within a system that involves ranking. Vertical segregation looks at a particular occupation, or set of occupations, to see how people from different social groups occupy different levels within that occupation. Figure E-4-2, using data from the U.S. National Science Foundation, shows the distribution of women and men across the ranks of U.S. doctoral-degree mathematics faculty. Typically, faculty in the full and associate professor ranks also hold tenure, while those in the assistant and instructor/lecturer ranks are not tenured. Each rank represents a level of additional advancement over the previous one. While women are split nearly equally in the two senior ranks and the two junior ranks, more than half of male doctoral-degreed mathematics faculty were full professors. Altogether, about 80 percent of men faculty in mathematics held relatively secure and powerful positions, while women were more likely to be in lower-level positions. Further, one-in-ten women mathematics faculty holding doctoral degrees were in what are often considered the least secure and least powerful positions as instructors/lecturers.

FIGURE E-4-1. Horizontal Segregation: Representation in Mathematics Subfields by Sex of Doctoral Degree Recipients, 2007-2008

SOURCE: Authors’ Analysis of data in Phipps, P., J.W. Maxwell, and C.A. Rose. 2009. 2008 Annual Survey of the Mathematical Sciences in the United States. Notices of the AMS 56(7):828-843.

FIGURE E-4-2. Vertical Segregation: Faculty in Mathematics by Sex and Rank of U.S. Doctoral Degrees in Mathematics, 2006

SOURCE: Authors’ Analysis of Data in NSF. 2009. Characterisitics of Doctoral Scientists and Engineers in the United States, 2006, Detailed Statistical Tables NSF09-317.

Metrics associated with both of these dimensions have been developed and well-articulated in the literature. Some metrics were originally developed by demographers to measure residential segregation. Over time, these measures have been subsequently refined to measure differences between groups in their placement in occupations or fields of study. These metrics, which are typically normalized in an appropriate way, permit analysis across different contexts (national, institutional—i.e., university level, different fields or disciplines) and across time. Later work will develop and apply these metrics to occupational segregation in computer science, mathematics and statistics, and the chemical sciences in greater detail.

Middle Level

What explains the horizontal and vertical segregation shown at the macro level? What are the underlying causes of the gender segregation? How do these factors differ at various stages and levels of a scientific career? Middle level analyses focus on the processes and institutional contexts in which new workers are recruited, trained and attain qualifications and advancement. How is gender a factor in these processes? Who makes the decisions within institutions, and to what extent are these decision-makers provided with information with which to judge potential workers? What are the biases in the information that is provided or in the processes associated with these judgments?

It becomes clear that complex processes are at work and that a gendered perspective is essential to understanding what has been metaphorically called the “leaking pipeline,” “the crystal labyrinth” and “the glass ceiling syndromes.” Examining processes within institutional contexts, such as workplaces and schools, will allow us to discuss some of these factors.

Terms like “leaking pipeline,” “the crystal labyrinth,” and “the glass ceiling,” all refer to the processes by which workers enter and move through jobs in organizations. The “leaking pipeline” metaphor is often used in contexts that suggest that individuals’ choices are often viewed as the source of the leakage. The terms “crystal labyrinth” and “glass ceiling,” however, are not completely value-neutral, embodying the notion that the processes by which women are segregated into lower level or less powerful positions operate like the invisible hand in the market, and that these processes that produce outcomes, such as those shown in Figure E-4-2, are not visible.

The term “work-family balance” has entered the lexicon to understand the lower participation levels of women in various areas of science and for different rates of advancement of women and men in those areas in which women may already have achieved parity at the entry level. When the former is used, the word “family” invokes images of gendered domesticity that connect the concern with this balance to women. Recently, in recognition that there are various non-work issues that need to be balanced with work, the term “work-life balance” is becoming more popular. Regardless of the term, this issue is raised as a common explanation for women’s lack of advancement in science fields as due to women’s greater connection to family, necessitating trade-offs of career advancement and family balance.

Why are men more likely than women to be in higher-level faculty positions, as shown in Figure E-4-2? Metaphors like “the glass ceiling” or the “crystal labyrinth” suggest that perhaps the institutional processes of advancement in higher education settings are not visible to women but they are to men. Invoking explanations using terms like “work-family balance,” however, suggest that perhaps women are more likely than men to choose to attend to family matters to the detriment of their careers.

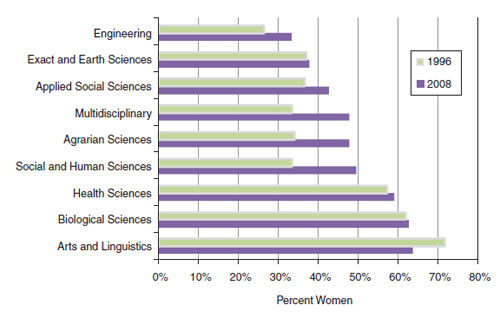

Figure E-4-3 shows horizontal segregation of women among doctoral degree recipients in Brazil in 1996 and 2008. If metaphors like the “leaky pipeline” are invoked, then why are there such broad variations across fields in women’s participation? That is, why is women’s representation in some STEM fields so low, while women have a higher level of representation in other fields? Why are these gender differences more pronounced in the United States and other affluent countries than in transitional and developing countries? As shown in Figure E-4-3, one third of doctoral degrees in engineering were awarded to women in Brazil in 2008, while in that same year in the United States, just 20 percent of doctoral degrees in engineering were earned by women.

FIGURE E-4-3. Women’s Representation among Ph.D. Recipients in Brazil by Field, 1996 and 2008

SOURCE: Doutores Estudos da demografia da base técnico-científica brasileira - Brasília, DF: Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos, 2010.

Micro Level

At the micro level, we shift our focus closer to the individual level in relation to the institutional level processes just considered at the middle level. At this level we are particularly interested in the calculus of choice. Here we reach what can often be a slippery slope: while we can conceptualize individuals as active agents of their own lives, the extent to which individuals are effectively channeled into some areas or blocked out of others can represent significant constraints on these choices. To what extent do the choices about careers and curriculum of individuals continue to be made along gender lines? To what extent do actors possess accurate

and full information about these fields? What are the situations in which individuals find themselves and how do these situations impact the choices that they make related to fields of study and careers?

For example, return for a moment to the issue of “work-family balance.” Women and men face the same question: How do I balance the needs of my family with those of my employer and/or my career? But the decision about this balancing act is made within a particular social context and then within a particular household situation. The choice made by the household about, say, care of minor children is influenced by many factors including: the presence of affordable, high-quality daycare; employers’ willingness to permit workers to leave earlier in the afternoon to attend to children; the relative income provided by each member in the couple; and social norms related to gender and the care of children.

SUMMARY

This paper provides a framework within which to understand segregation processes at three levels: macro, middle and micro. Measurement tools at the macro level in this chapter provide metrics with which to make comparisons of segregation in computer science, mathematics and statistics and the chemical sciences across work contexts (e.g., industry, government, and academia), across nations/economies, and across time. Theories at the intersection of social organizations and the social construction of gender reveal how institutional processes, at the middle level, play a role in occupational segregation. Finally, at the micro level, individuals’ interactions and choices, as well as the constraints and meanings of those choices, can be analyzed to understand the gendered outcomes associated with decisions about education and work.