5

Residential Energy Consumption Survey Program History and Design

This section details the panel’s recommendations for redesigning the Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS). During the panel’s deliberations two areas emerged as the top priorities for revision: (1) the timeliness and frequency of the CBECS and (2) data gaps. Thus a discussion of these two topics follows, along with the panel’s recommendations for changes in these areas. Some of the recommendations involve major changes in the way the survey is administered; ideally, these changes would all be implemented together, so as to maximize the benefits. The major recommendations include implementing a rotating sample design with a longitudinal element for part of the sample and transitioning to a multimode data collection. The second half of this chapter offers additional suggestions for updating the CBECS with changes that are more incremental in nature.

TIMELINESS AND FREQUENCY OF THE CBECS DATA

The panel’s research, including discussions with users of the CBECS data, showed that one of the biggest concerns about the CBECS is the delay that often occurs between the time the data are collected and the time they are released to the public. For example, the public-use microdata file for the 2003 CBECS was released in November 2008. A related issue is the survey’s quadrennial schedule, which does not meet the legislative requirements and is considered inadequate by at least some of the data users. An important aspect of this concern is simply the face validity of data that have been

collected years before publication. In addition, data users argue that some characteristics of building energy consumption change relatively frequently and therefore that energy consumption data would be more useful if they were captured on a more frequent basis.

Just before this report went to print, the data that had been collected for the most recent CBECS were deemed unusable four years after the reference period (2007). Even in the best case, the result would have been an eight-year time lag between one round of the survey and the next round that was usable. However, a decision to suspend the 2011 data collection because of insufficient funding will make the lag even greater. These are unusual circumstances, and they have put stakeholders who rely on the CBECS data for research and decision making in a very difficult situation.

For the purpose of discussion in the sections that follow, the panel assumes that the CBECS data collection will resume on at least a quadrennial schedule in fiscal year 2012.

Rotating Panel Design for the CBECS

One option for addressing data users’ need to have quicker access to the data is to implement a rotating sample design, which would make more frequent data releases possible. This could be done by dividing the sample into four subsamples and collecting the data over a four-year period, instead of once every four years. Data could then be released annually, with each release containing one year’s worth of new data combined with data from the previous three years in order to achieve a sufficiently large sample size that will enable EIA to release an amount of data that is comparable to what is released under the current design.

This design would have several advantages, besides offering faster access to the data. For example, while the goal would be to have roughly the same number of completed interviews at the end of the four-year cycle as would have been collected with the standard pattern of collecting data once every four years, with self-contained annual samples, the rotating design would not require a commitment to four full years’ worth of interviews upfront, which could be an advantage if fluctuations in CBECS funding persist. The continuous sample design would give EIA more options when faced with a substantial budget cut, for example, by making it easier to reduce the sample size without having to sacrifice the entire survey. Furthermore, the new design would also increase EIA’s ability to be flexible in terms of testing new data collection approaches because testing could be performed on one year’s

sample (or a subset of one year’s sample), and the procedures could be fully implemented—or revised, if necessary—for the following year’s sample. In some years, there will be some overlap in the reference period for the data collected by the three energy consumption surveys, which could also have some analytic advantages.

Although the transition to a new sample design and new data collection operations will involve some temporarily increased costs compared to the typical start-up costs associated with the current design of the survey, the expectation is that, at least for the most straightforward implementation of the rotating design (Option 1 described below), over time the costs would be at least comparable—and possibly lower than—the cost of conducting the survey once every four years. EIA could phase in the first subset of the sample gradually, for example, over the course of a two-year period, instead of aiming to complete a quarter of the interviews during the first year of the implementation.

An operational advantage is that the survey would not have to be resurrected every four years, and there may be some cost savings and data quality improvements associated with uninterrupted operations, since there would be more continuity in the activities performed by staff and, in particular, the field interviewers, who require extensive training. It is possible that the decrease in the number of interviews conducted each year might lead to a decrease in efficiency in terms of ability to provide interviewers with an optimal caseload in their respective geographic areas. However, as discussed later, the panel encourages EIA to explore the possibility of collecting some of the data by web, which would also contribute to a drop in the field interviewer workload and would likely necessitate the restructuring of interviewer assignments. This could be accomplished, for example, by crosstraining interviewers to perform additional tasks.

The rotating design would also integrate well with a longitudinal approach, which would involve following a subset of the sample over time. This would improve estimates of change and would allow researchers to assess how changes in the economy or in incentive programs affect energy consumption patterns. EIA experimented with longitudinal data collection for the CBECS in the 1980s but found that inconsistencies in reporting and other sources of error were sometimes confounded with the actual changes of interest, which limited the usefulness of the longitudinal data (French, 2007). However, techniques for reducing inconsistencies and controlling for confounders in longitudinal studies have become more sophisticated

since that time (Lynn, 2009), which could make longitudinal data more useful now.

Data collection costs for the longitudinal subset of the sample are expected to be lower in the long run than collecting the same number of data points on a different sample every year, because information associated from the first contact with the respondent can be used to reduce the costs of the second interview. At the minimum, information about the building and the designated respondent will be useful in reducing operational costs, especially if an email address can be obtained to conduct the second interview by web. It would also be possible to significantly shorten the questionnaire and to only ask respondents to update their responses, as needed, carefully wording the questions to reduce concerns about possible biases related to the repeat interview.

The value of changing the frequency of the data collections and introducing sample overlap between different rounds of the survey will depend on a number of factors, both user-driven (e.g., the importance of estimates of change and the importance of having more frequent estimates) and technical (e.g., the correlation over time of key variables and cost implications due to changes in field operations). Although the panel cannot fully assess these factors as they apply to the EIA energy consumption surveys, it is able to suggest options that should be explored using real data.

It is worth noting that although the discussion in this section focuses on CBECS, similar approaches could be applied to the RECS as well. For simplicity’s sake, the discussion in this section will be based on the assumption that CBECS has funding for a sample of 6,000 buildings every four years under the current design. The discussion will refer to the process of collecting data as “interviews” even though, in practice, data may be collected by various other means, such as via the web.

The discussion will focus first on two specific options, one of which involves including some of the buildings in the sample twice. The discussion of the two specific options is followed by a discussion of generalized versions of these options. All options presented are special cases of Option 5, so readers familiar with rotating panel designs may wish to read that section of the text first. Ultimately, EIA will have to evaluate which approach is most suitable for the CBECS, but the panel believes that an overall assessment of the costs and benefits of introducing a rotating sample design should receive priority as part of EIA’s planning for the near future.

Option 1: Full Rotation

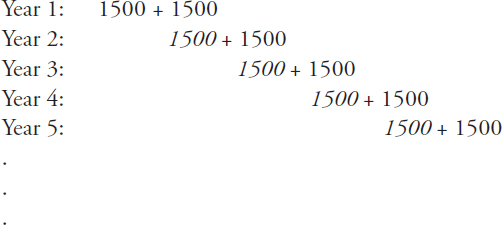

In Option 1, the data collection that currently takes place every four years is spread evenly over four consecutive years. That is, instead of sampling 6,000 buildings every fourth year, 1,500 buildings would be sampled in Year 1, a different set of 1,500 different buildings would be sampled in Year 2, and so on. An obvious advantage here is that it is possible to produce estimates that are more up to date (for example, by taking a four-year moving average every year). A disadvantage is that a “sharp snapshot” estimate taken once every four years is replaced with a “fuzzy” one taken every year. To be more precise, if ![]() is the parameter of interest, then the annual estimates

is the parameter of interest, then the annual estimates ![]() … are replaced by estimates formed by taking averages over four years, such as

… are replaced by estimates formed by taking averages over four years, such as ![]() Of course, it would still be possible to estimate

Of course, it would still be possible to estimate ![]() using data from only Year t, but the estimate would be based on only one-quarter of the current sample size. Depending on the details of how the sample is distributed over the four years (e.g., spread within primary sampling units or across them), there may be significant operational disadvantages as well.

using data from only Year t, but the estimate would be based on only one-quarter of the current sample size. Depending on the details of how the sample is distributed over the four years (e.g., spread within primary sampling units or across them), there may be significant operational disadvantages as well.

Option 2: 50% Rotation

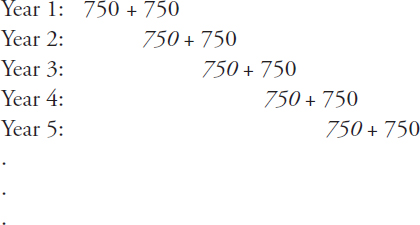

In Option 2, the rotation pattern would be as follows, with numbers in italics denoting buildings that are in the sample for the second time:

Once the pattern has stabilized (i.e., after the first year), each building is in the sample twice. Thus the number of unique new buildings in the sample remains at 6,000 over a four-year period, but the number of interviews doubles to 12,000.

In this approach, as in Option 1, it is possible to use the data for various estimates, including ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() A major advantage of the rotation pattern in Option 2 is that it makes it

A major advantage of the rotation pattern in Option 2 is that it makes it

possible to use composite estimation to improve the estimates. Composite estimation1 can be useful in this context because this is one method that can help exploit the overlapping sample (i.e., the fact that, for a given year, half of the sample overlaps with the sample from the previous year) to gain efficiency (reduced variance). The efficiency gain depends on the correlation over time for the variables of interest—the greater the correlation, the greater the gain. Of course, the existence of sample overlap also greatly improves the quality of year-to-year estimates of change. An operational advantage of this option is that most second interviews can be conducted more cheaply (e.g., by telephone or via the web), with personal visits necessary only for nonrespondents. A disadvantage of this option is the increased burden on respondents since they would be interviewed twice rather than just once.

A much less expensive variant of Option 2 would be to keep the number of interviews (as opposed to buildings) steady at 6,000 every four years:

In practice, a compromise between the two variants seems reasonable. The gains in statistical efficiency offered by the first variant of Option 2 can be translated into a reduction in sample size for fixed variability. However a 50 percent reduction in sample size would likely be too big for most variables of interest. A suitable reduction in sample size would be determined by deciding which variables are key ones, estimating their variances under different sample size reduction scenarios, and picking a scenario that balances costs and quality.

Option 3: (100/R)% Rotation (Generalization)

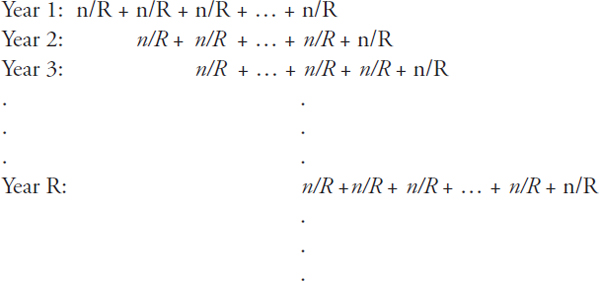

Option 3 is a special case of a more general rotation pattern with R rotation groups or panels (R = 2 in Option 2). In general, there would be

![]()

1 For further details on composite estimation, see Appendix E.

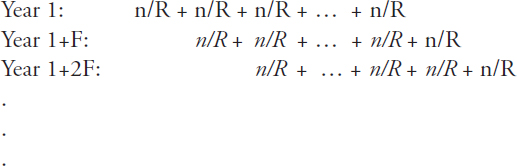

n/R buildings in each rotation group, where n is the number of buildings (old and new) sampled in one year. As illustrated below, each year n/R new buildings enter the sample, and an equal number drop out of the sample. The part of the sample that is common between two consecutive years is displayed in italics (and thus nonitalics denotes a fresh sample).

The year-to-year overlap in sampled buildings would be 100(R – 1)/ R%, and each building would be in the sample on R occasions. Therefore, as R increases, so does the proportion of overlap between years, which will result in better estimates of change and better composite estimates. On the other hand, the response burden will also increase since each unit will be subjected to R interviews. Another disadvantage of having a larger value of R is that there is a longer start-up period (R years) before the rotation pattern stabilizes. That is, up until the Rth year, there will be some buildings that stay in the sample for fewer than R occasions.

Note that setting n = 3,000 and R = 2 gives us variant 1 of Option 2, and setting n = 1,500 and R = 2 gives us variant 2 of Option 2. Option 1 is the “degenerate” case with n = 1,500 and R = 1. (To see this, simply erase all the terms in italics for Years 2, 3, … and note that there is only one term in Year 1, namely n/R = 1,500/1 = 1,500.)

Option 4: Preserving the Four-Year Gap Between Surveys

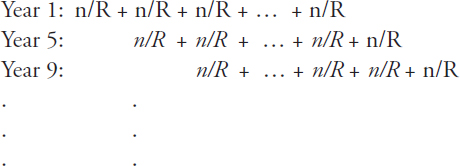

A different approach is to introduce sample rotation while continuing to conduct the survey every four years instead of every year. Any of the previous options can be applied by simply changing years 1, 2, 3, … to years 1, 5, 9, … Thus, the general case (Option 3) becomes:

Having a four-year gap for a rotating panel design would have some disadvantages. One would be the possible attenuation of correlations over time, which could make it impossible to construct a reliable composite estimator for more than a small subset of the variables. In addition, there may be operational impacts caused by the large volume of building changes likely to be observed in the overlap sample following a four-year gap. Building occupants would also be more likely to change during the four years between interviews, complicating the reinterview process and introducing another confounding factor.

Option 5: F-Year Gap Between Surveys, with Rotation

The most general option along these lines would be to have R rotation groups for a survey that is conducted every F years:

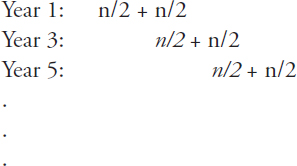

Here F can represent any number of years, but a small value is preferred since correlations weaken over time. Setting F = 2, for example, would offer a compromise between conducting the survey annually and having a four-year gap between surveys. If buildings were surveyed every two years, the correlations for some key variables might still be high enough to yield good gains using composite estimation. The case R = 2, F = 2 is illustrated below.

Thus, with a sample size of n = 6,000, the survey would include 6,000 buildings visited every other year, with 3,000 of these being new buildings and the other 3,000 being second visits (starting in Year 3).

Additional Considerations

The above is by no means a comprehensive list of options. The goal of this section is to show that there are many alternatives to the current design that are worth consideration. For example, an approach inspired by the rotation pattern used by the Current Population Survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics would be to have a building in the sample one year, then out of the sample for one or more years, and then back in the sample in a later year. Regardless of which approach is chosen, data releases should be accompanied by enough technical documentation about the survey design and data collection procedures that users can understand the limitations of the data and select appropriate methods for analyses.

Recommendation CBECS-1: EIA should evaluate the usefulness of implementing a rotating sample design for the CBECS to improve the timeliness of the data.

Recommendation CBECS-2: EIA should consider integrating a longitudinal element into the CBECS sample design to obtain better estimates of change.

CBECS Multimode Data Collection

Another strategy for increasing the timeliness of the data releases would be to change some of the interviews from face-to-face settings to collecting data via the web. This could shorten the data collection period significantly, and make data processing and release times faster. Nonpersonal interview modes of data collection are likely to be both necessary and very useful when

implemented in conjunction with a design based on the recommendations in the previous section. An additional methodological benefit of speeding up data collection would be a shortening of the reference period, which would result in the data capturing a narrower, more precise window in time.

Although EIA has in the past considered using other modes of data collection, at this time CBECS data are still collected primarily by in-person interviewing. One reason is the initial cost of implementing a new data collection mode. Another reason is the complexity of the CBECS data collection procedures and questionnaires. With the current system of face-to-face data collection, the field interviews play a significant role in dealing with these complexities. For example, field interviewers are trained to apply CBECS definitions to determine the boundaries of a building and to identify the most appropriate respondent for the survey. They also mediate an elaborate editing and error-resolution system that is currently built into the computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI), and they carry hard-copy “show cards” that list the answer options for specific items and which can be handed to the respondent to assist with answering questions that may be too difficult to remember if they are only read by an interviewer. Interviewers also collect and scan utility bills when these are available. Finally, the involvement of field interviewers can often lead to higher response rates to the survey in general and to individual questions as well. Field interviewers can locate sample units that are difficult to find through other means and they can often persuade a reluctant respondent more effectively than a contact through another method, such as the telephone, mail or web. Field interviewers can also make sure that all of the questions are answered without break-offs, which reduces the levels of missing data for individual questions.

The panel acknowledges the advantages of face-to-face interviewing and that some of these may be lost by implementing other modes of data collection. However, given the costs associated with in-person data collections and the role of the Internet in today’s society, it is difficult to imagine that a large-scale nationwide survey based solely on face-to-face data collection will be sustainable in the long run. The panel believes that EIA has to make it a priority to begin preparations for implementing a multimode data collection approach which will have at least a portion of the interviews being conducted online.

Although issues associated with transitioning to a new data collection mode are faced by many other large-scale surveys, some of the challenges and opportunities are more specific to the CBECS. The upfront costs of introducing a new data collection mode will be significant, but some of the

costs associated with the transition may be lowered if the sample design is changed to continuous measurement. The new design will allow EIA to test and revise procedures on a subset of the sample, and implement improvements on an annual basis (and often faster). Transitioning at least a subset of the buildings to the web will free up some resources after the initial implementation period, and these resources can then be allocated to the more complex cases and possibly invested into increasing the sample size. Once a web questionnaire has been built and tested, there are virtually no costs associated with the actual individual web interviews, in contrast to face-to-face interviewing, for which cost is directly related to the number of cases. Obviously, introducing a web data collection mode does not mean that follow-up, editing, and other data collection costs can be eliminated, even for the interviews that are conducted over the web.

Collecting technical data of this nature on the web does present some methodological challenges (for example, selecting the appropriate building respondent without a face-to-face visit will be more difficult), but there is a vast and growing methodological literature concerning how best to transition data collections from one data collection mode to another and how best to integrate multimode approaches (see, for example, de Leeuw, 2005; Dillman and Smyth, 2007; Dillman et al., 2008). Based on the findings in this literature, the panel believes that these methodological challenges can be addressed. The panel also strongly encourages EIA to develop its own methodological research program to help inform the transition to web data collection in those cases where the current literature does not have adequate answers.

It is also important to note that there are certain methodological advantages associated with web data collection, including the possibility of embedding visual and other multimedia aids into the questionnaires and also the availability of metadata about each interview, which can be useful in fine tuning the data collection approach.

The panel recognizes that enabling this transition will require that difficult decisions be made in terms of eliminating some of the complexities in the data collection procedures and questionnaires. In particular, the editing and error-resolution system that is embedded into a computer-administered instrument but that relies on an interviewer to navigate will have to be revised. Furthermore, some steps will have to be eliminated altogether in order to avoid situations in which the burden of resolving unusual errors is transferred from the field interviewer to EIA staff, possibly causing further delays in the release of the data. While many of the complex procedures in

question were originally introduced to improve data quality, some data users indicated to the panel that they would gladly accept less thoroughly edited data in the interest of faster access. The topic of postsurvey editing will be discussed further in the next section.

One possible approach that should be explored as part of a gradual transition to the web is to divide the sample into two sets: buildings that can be transitioned relatively easily to a web administration and buildings with more complicated characteristics that may benefit from interviewer administration. It may also be necessary to treat large buildings differently from smaller ones. A review of the case histories and interviewer debriefings would be helpful in identifying the building types for which data collection is fairly straightforward. Given that some of the data collection complexities are associated with defining building boundaries, buildings that are in the sample during more than one year and have already been visited during a previous round of the CBECS (typically large buildings) may be especially good candidates to move to the web once one or more in-person visits have been completed and the boundaries have been ascertained. This strategy could be implemented regardless of whether a longitudinal element is introduced in the sample design.

Until reliable auxiliary data sources can be integrated into the data collection process, a first in-person visit to each building may still be useful, especially if it is decided that the first interview in a longitudinal series will be completed in person. During that visit, interviewers should follow a protocol developed by EIA to determine if the building is a good candidate for a web response. Given the concerns related to the definition of a building, the decision whether to transition a case to the web will likely depend in part on whether the definition seems straightforward—as it would be, for example, for a small, standalone building occupied by one tenant. Resources should be invested in testing ways to communicate the definition of a building through a self-administered format, in anticipation of transitioning more and more complex buildings to web administration in the future.

The best way to collect contact information for a web survey should be explored as part of the methodological research program. Possible options include obtaining the information during the first visit or obtaining it by telephone. Alternatively, information on how to access a web survey can sometimes be included in a hard-copy advance letter.

An important consideration is the possible impact of the web administration on response rates. This question has been receiving a great deal of interest as more surveys are moved to the web. Recent research has found

that augmenting multiple postal letters with supportive emails can be a successful strategy that combines the advantages of both modes of contact and which leads to web-only response rates that are comparable to mail response rates (Millar and Dillman, 2011). The postal letters help establish the importance and legitimacy of the study, while the emails reduce the burden of responding by web because they contain both the link to the survey and the necessary log-in information. Regardless of the initial strategy used, for the foreseeable future the CBECS will likely require at least one additional mode of contact to allow follow-up with sample members who do not respond by web and to assure that response rates do not drop below current levels.

There is no question that identifying the best respondent for completing the interview is crucial in the case of the CBECS, but ways of accomplishing this without involving an interviewer should be explored. It is possible that a web option could actually result in more interviews being conducted with qualified respondents. In some cases, for example, it may be easier to forward a questionnaire to the right person than to locate him or her in a building and arrange an interview. Furthermore, in-person interviewers may have an incentive to complete an interview as quickly as possible by settling for a willing respondent rather than pursuing the most appropriate one.

If a questionnaire was available on the web, it would be easier for several respondents to collaborate, each completing the sections that he or she is most knowledgeable about. A web option could also result in more complete data because it would give respondents the option to pause the survey while they obtain information to answer questions they are not sure about and then resume the survey later. Naturally, if respondents pause while responding to the survey or forward it to someone else, there is a risk that the questionnaire will not be completed at a later time, so an extensive follow-up effort is likely to be necessary. However, when a topic is too technical for many respondents, such as is the case with the CBECS, this kind of follow-up could make a significant difference in data quality.

Currently, the face-to-face CBECS interviews rely heavily on hard-copy show cards. However, transferring the show cards to the web, especially following a unified-mode construction approach, will have significant methodological advantages. In a web survey, show cards are effectively built into the questionnaire and placed directly into the path respondents follow as they go through the survey. Thus respondents can focus on the question-

naire, as opposed to having one eye on the interviewer and one eye on the show cards.

The use of hard-copy show cards also raises the concern of possible biases introduced by the order in which the response options are listed, especially because many of the show cards contain a large number of answer options, which can make it difficult for respondents to focus equally on all of them. For example, the show card listing the answer options for the primary activity in the building contains 16 items, and a respondent for a building with multiple activities may be tempted to select the first one that is applicable as the “primary” activity instead of carefully reviewing the entire list. A web questionnaire would make it easier to restructure these questions into layered sets of items with fewer answer options, or to reduce the possibility of primacy effects by using various innovative methods, such as the animated presentation of response choices or an eye-catching emphasis on the end of the list.

Testing will be required to determine the best way to ask questions that EIA has identified as being challenging because of their technical nature. For example, different approaches to obtaining the square footage information from respondents can be tested in split-sample experiments. Deconstructing this kind of an item into a series of questions would introduce complex skip patterns, but the changes would be easy to implement on the web without increasing the cognitive burden on respondents. Furthermore, a web-based survey could integrate various aids and tools for respondents, such as definitions or diagrams that can pop up if a respondent requests help or seems to be having trouble with a question. Interviewer debriefings would be particularly useful in pinpointing specific questions that could benefit from a different approach.

As is always the case with self-administered surveys, it will be valuable to provide respondents with an email address and toll-free telephone number they can use if they have questions. The staff members who respond to such inquiries should be able to provide assistance related to the technical topics in the questionnaire and to answer questions specific to the web administration.

Finally, when evaluating the implications of transitioning to a mixed-mode administration, it will be important to consider the options available for collecting the utility bills that are currently collected during the interview. Some respondents may be able to upload electronic copies of their bills through the questionnaire website, and this option should be explored. Asking respondents to mail a copy of their utility bills would likely require

extensive follow-up, but it is unclear whether this approach would still be more cost effective than multiple in-person visits to a building. Another possible solution is to increase reliance on supplier data, as discussed later.

Recommendation CBECS-3: Informed by a methodological research program, EIA should begin developing procedures for a multimode approach and should begin moving some of the CBECS data collection to the web.

Revised Editing Procedures for the CBECS

CBECS data undergo a complex series of edits to locate and correct errors in the recorded responses in order to increase accuracy. Data errors are inevitable even in surveys on straightforward topics, but they are a particular problem in surveys like the CBECS because of the technical nature and difficulty of the questions. According to EIA, the items in the CBECS that require the most editing are the questions about building equipment.

Postsurvey editing is particularly resource intensive, and it is a major contributor to the time required to prepare the data for public release. The editing standards and, in particular, the optimal extent of the data editing have been the subject of debate among survey researchers and analysts, with some arguing that federal government surveys tend to suffer from “overediting” (Weisberg, 2005).

For a typical CBECS, the editing process consists of CAPI edits that are built into the computer-assisted interview software and occur in real time, while the respondent is completing the survey, and postsurvey edits that occur after the interview is completed. The CAPI edits include

• Warnings about possible inconsistencies in the reporting (for example, if a respondent reports that a building has six floors, and answers “No” to the question about whether there are any elevators, a question pops up that asks the respondent to verify that the answers recorded to both of these questions are correct). Interviewers can revise the responses or “suppress” the warning if the answers recorded were correct.

• Checks for blatant errors (for example, if the building activities reported do not add up to 100 percent, an error message pops up pointing this out). These types of error messages cannot be sup-

pressed. The responses have to be corrected before the interview can proceed.

• Automatic recodings, including responses derived from answers to previous questions, intended to minimize response error and burden (for example, a library building on a college campus is considered a public assembly for the purposes of the CBECS, and it is recoded as such if the respondent describes it as an education building). These types of edits happen automatically and do not require an action from the respondent or interviewer.

Because the CAPI edits are built into the interview program, they are not as resource- or time-intensive as the postsurvey editing steps. While some of the postsurvey checks are automated, the editing is almost always based on manual review, and sometimes requires a callback to the building. The types of edits that take place after the interview include

• Editing for critical items that cannot be wrong, missing, or machine imputed. These items include, for example, square footage; number of workers; year constructed; operating hours; energy uses; energy sources; and percent heated, cooled, or lit. With some exceptions, the editing rules require a callback to the building if the answer to a critical item is missing or appears to be incorrect based on plausibility tests run after the interview (for example, if the square foot per worker and square foot per floor were both higher than the 95th percentile of those ratios from the previous CBECS). Because a callback to the building is often required, the timing of these edits is important and was a concern in the 2007 CBECS when the data collection contractor failed to perform these tasks once the interviews were completed.

• Miscellaneous edits (for example, recoding of “other, specify” answers; verification that buildings coded as enclosed malls are indeed enclosed malls; checking possible inconsistent responses such as a report about a building that has a high-density computer room but no servers, or a government-owned building that does not have any government entities occupying space in the building). Each of the cases in this category is reviewed individually.

• Comprehensive edits of the final CAPI, critical or miscellaneous edit failures. After the data are delivered by the contractor, EIA manually reviews every case that met one or more of the following

criteria: failed selected CAPI edits (with some modifications) that were not resolved during the interview, failed a critical edit, failed a miscellaneous edit, or failed an edit specific to the consumption and expenditure data.

EIA also manually reviews cases that contain an interviewer remark or responses to “open-ended” questions as well as other questions that accept verbatim responses instead of a precoded answer category. This includes, for example, other building activities; other types of heating equipment; other types of separate computer areas; and the explanation from a respondent who reports only a boiler, only a furnace, or only district heat as the heating equipment but reports more than one energy source.

Although it is not, strictly speaking, an editing procedure, imputation, or the filling in of missing values that still remain after the editing, is another important step that takes place after the survey is completed. This is done using a hot deck imputation method and is limited to the items that are considered important enough that they cannot be left blank. The most frequently imputed CBECS items include square footage and year of construction. For the 2003 data, the imputation rates for these two items were both around 10 percent.

EIA has been planning to revise the CBECS editing procedures because it believes that these procedures could be streamlined and improved. The panel agrees that an evaluation of the editing procedures is necessary to determine whether the data are “overedited” and whether changes could be made to accelerate the processing of the data. As discussed in the previous section, emphasis should be placed on a shift to editing procedures that can be implemented in a self-administered setting to facilitate the integration of a web data collection mode. This could include revising the warning and error messages that pop up during the interview to make them suitable for self-administration and evaluating whether more of the CAPI edits that currently involve warnings could be handled automatically. The manual edits should also be reviewed with an eye toward simplifying the process in order to facilitate faster processing of the data. The review should identify any editing rules that are particularly resource intensive but that contribute relatively little to increasing data quality overall, for example, because of the small number of cases involved. In addition, it may be possible to transfer some of the postsurvey editing that is currently performed manually to automatic processing if a review indicates that there are standard decisions that tend to be applied to resolving some of the problems. Finally, to the

extent some of the edits will continue to require a callback to the building, a review of the processes in place to assure that these are performed promptly by the data collection contractor may be necessary.

To determine which aspects of the editing process can be simplified, automated, or eliminated, EIA should conduct an analysis to determine the impact of the current editing procedures on data quality. Comparing data from the previous CBECS from before and after the editing process should be useful in identifying specific editing rules that may not improve the data sufficiently to justify the time and resources invested into pursuing the revisions. In some cases, the conclusion may be that a certain amount of error is an acceptable consequence of the technical nature of the survey and that editing does not eliminate this particular problem.

In addition to a possible reduction in the time required to process the data, revised editing procedures could have the additional benefit of substantial reducing the staff time that is currently dedicated to this process. If some of the staff time could be freed up by eliminating some of the editing steps, EIA would be able to invest these resources into the start-up work required to implement a rotating sample design and web data collection. Staff would also have more time to research and evaluate the costs and benefits of some of the panel’s other recommendations, discussed later.

As an alternative to, or in combination with, the above changes, the possibility of releasing a preliminary data set with only a subset of the variables edited, prior to the release of a fully edited data set, also needs to be evaluated. Because many data users have very focused interests and typically use only a subset of the data, releasing some of the variables before the full data set is edited could provide some researchers with earlier access to all of the variables that they need. To the extent that the editing steps for some of the variables are interconnected, care will have to be taken to avoid releasing data that later may have to be further edited based on checks performed on other variables.

Recommendation CBECS-4: EIA should investigate strategies for releasing the CBECS data faster, for example, by revising the editing procedures or by completing the editing for a subset of the variables and releasing these data prior to completing the editing for the full data set.

CBECS DATA GAPS

The current CBECS sample design is best suited for producing descriptive statistics at the national, census region, and census division levels. However, each building in the CBECS is also assigned a climate zone, based on the 30-year average of heating degree-days and cooling degree-days from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) climate division in which the weather station closest to the sampled building is located (see Appendix D). NOAA climate divisions are regions within a state that are climatically homogeneous.

One of the major limitations of the CBECS is a lack of granularity in the data it provides. The sample design—and, in particular, the sample size—limits the analyses that can be conducted on the data, not only geographically but also in terms of the level of complexity. It is especially difficult, using the data that are currently available, to perform multivariate analyses to assess the impact of policy decisions or to explain changes in energy consumption.

A CBECS sample size of approximately 6,000 cases represents nearly 5 million commercial buildings. While this is small in an absolute sense, the size limitations are exacerbated by other factors, such as the inherent variability among buildings of different sizes and activity types, high relative standard error (RSE) thresholds, and the strict confidentiality protections that are designed to prevent survey data from being linked to a specific building (and thereby tenant), and which limit the data that EIA is able to release even further. In other words, some of the most pressing “data gaps” identified by data users are in fact limitations imposed by factors associated with the sample size rather than shortcomings associated with the content of the questionnaire.

Researchers could benefit greatly from having survey information that is broken up into finer geographical divisions. This need is also emphasized by a recent assessment of state energy data needs conducted by EIA (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2009). State-level data would be more useful than data divided by census region or census division because of the differences that exist among states in a variety of characteristics, ranging from climate to policy. At a minimum, researchers would like to have more information about a building’s geographic location—specifically, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers climate zone—as well as state information associated with the summary statistics. The fact that this information is not currently available

from the survey severely limits the analyses that can be performed and thus the usefulness of the data.

Perhaps even more important for researchers is information about the principal building activity (which EIA defines as the activity or function occupying the most floor space in a building), given that this plays a major role in understanding building energy consumption. EIA groups principal building activities into categories of activities that have similar patterns of energy consumption (for example, office, health care, lodging, and mercantile and service). Since 1999 the CBECS has been classifying building activities into more than 100 different categories, but small sample sizes and the resulting statistical and confidentiality limitations make it necessary to combine these fine-grained categories into 16 broad categories when the data are published. Specific building types that are of interest to researchers include data centers, laboratories, convention centers, and arenas—and there are probably others as well—and these needs have to be evaluated and prioritized.

One addition to the survey that could help data users better understand trends in the building sector would be to provide oversamples of new construction for use in assessing the degree of compliance with building energy codes. Data on renovations and retrofits would also be of value, particularly when the remodeling has been done to incorporate energy efficient designs, systems, and equipment. Researchers could also use larger samples of those buildings that have received leadership in energy and environmental design (LEED) or Energy Star certification. If these designations could be made available as part of the data released, it would be possible to compare the characteristics and energy use of buildings that have an energy efficiency certification with those that do not. As discussed in the panel’s letter report (see Appendix F), an oversample of buildings for which some data are available from sources other than the CBECS interviews would allow researchers to make comparisons between the two data sources and thus achieve a better understanding of possible data quality issues with the survey. In the case of LEED and Energy Star buildings, some of the data submitted as part of the certification process are publicly available. An alternative to oversampling specific populations would be to incorporate some of these populations as a “take all” stratum in the sample, in other words, to include all known instances of these populations in the sample.

Another request from data users related to the sample and population of interest for the CBECS is to include buildings that contribute to energy consumption in the commercial sector but that are currently not in scope

due primarily to practical considerations. For example, an argument has been made for resuming data collection in buildings that are less than 1,000 square feet because even though they do not represent a large portion of the commercial sector energy consumption, there are a large number of buildings in this category.

Subsequent sections of the report will discuss a variety of data needs that cannot be met by the CBECS because of considerations related to the length of the survey and respondent burden. Given the difficulties related to addressing that challenge, it is especially ironic that, because of the limitations imposed on the data that can be released resulting from a small sample size and the associated quality and confidentiality rules, EIA is unable to at least maximize the usefulness of the data that have been collected.

One change that would make it possible to release more of the data that are currently collected, and to meet more data user needs without increasing the length of the questionnaire is to increase the sample size. A substantial increase in sample size would require a substantial increase in funding. However, this is an important factor in EIA’s ability to meet data user needs.

Recommendation CBECS-5: As part of its efforts to address the needs of data users, EIA should make it a priority to identify opportunities for increasing the sample size in order to enable the release of more of the CBECS data that are currently being collected.

Another option for making more data available to data users would be to establish a research data center (RDC) that would allow researchers to analyze restricted microdata either at secure sites maintained by a statistical agency or remotely, for example, by submitting computer programs to be run by the RDC. The safeguards that could be implemented through an RDC to protect respondent confidentiality would enable EIA to make accessible some of the data that are currently collected but that are restricted from use due to confidentiality concerns. Typically, data access to the research community as part of an RDC is provided on a project-specific basis. Researchers must submit a proposal describing why analysis of a specified set of restricted data is necessary to answer a particular research question, and the proposal is reviewed and approved only if it is determined that the project would not breach confidentiality. Statistical output that is generated during the use of the RDC is reviewed for disclosure risk before it is released to the researcher.

EIA might either establish its own RDC or collaborate with an orga-

nization that already has an RDC, such as the Census Bureau, which has RDCs housed at several universities and research organizations (http://www.census.gov/ces/rdcresearch/rdcnetwork.html [December 2011]), or the Center for Health Statistics, which has research data centers in Hyatts-ville, Maryland, and Atlanta, Georgia (http://www.cdc.gov/rdc/ [December 2011]). Exploring collaborations with existing RDCs may be the more cost-effective approach, because the start-up costs can be significant. A collaboration with an existing RDC will also require a dedicated budget, which EIA may have to secure through a separate funding request. However, wide dissemination of the data collected should be viewed as central to any statistical agency’s mission because it maximizes the data collection’s benefits to society (National Research Council, 2009).

Recommendation CBECS-6: EIA should consider establishing a research data center or evaluate the option of using an existing RDC maintained by another organization to provide data users with secure access to CBECS data that are currently not publicly released.

Increasing the sample size and establishing a research data center are recommendations aimed at maximizing the use of the data that can be collected with the current CBECS questionnaire. However, many data needs go beyond what is currently included in the survey. A CBECS interview takes on average between 30 and 45 minutes to administer, and it is a compromise between research needs and respondent burden. Respondent burden is an issue not only in terms of the time required to complete the survey, but also in terms of the difficulty of the questions. Any revisions to the questionnaire would have to take these factors into consideration, in addition to evaluating changing needs due to a changing energy landscape. Although the CBECS cannot—and probably should not—be expected to explain all aspects of energy use by any one building in the sample, it is important to periodically re-evaluate the questionnaire to make sure that any new uses that contribute significantly to a building’s energy consumption, or which have the potential to do so in the future, are captured by the survey. Setting practical considerations aside, if significant data gaps exist related to commercial building energy consumption, it would be most useful to the research community and policy makers if the gaps could be filled by EIA rather than by other organizations with even fewer resources or a narrower geographic scope. However, EIA is in the difficult position

of having to assess the mission of the CBECS and prioritize among a large number of competing needs.

Below, we list some of the data that researchers would like to see included in the CBECS. The list is by no means exhaustive, but it provides an illustration of the broad range of interests and possibilities for the survey.

• More information about building characteristics (for example, building orientation, wall insulation, length, width, height, floor-to-floor height).

• More information about roofs (for example, roof orientation, area, material composition, reflectivity, and insulation).

• More information about windows (number, window-to-wall ratio, orientation, and overall heat transfer coefficient).

• More information about building systems characteristics (for example, type of fuel used by each of the main building systems, sizes of heating and air-conditioning equipment, and the type of chiller system in the case of buildings using central chiller systems).

• Data about emerging end uses, such as data centers and plug loads, and existing end uses that are growing rapidly and that could become more important in the future (for example, because of climate legislation).

• More information about how much energy is used by specific end uses.

• Information about the efficiency ratings of end use equipment (ratings of fluorescent lighting of different sizes, such as T8 versus T12, energy efficiency ratio, seasonal energy efficiency ratio, annual fuel utilization efficiency ratings, and so on).

• Whole building energy performance data using national consensus building energy performance metrics.

• Information about the available outside parking area, which will be important to understand the potential space available for photovoltaic panels, especially for use in charging electric vehicles.

• More information about building operations (for example, the number of transactions in service and sales buildings, the percent occupancy in offices and hotels, the number of licensed beds in hotels, the number of beds in dormitories).

• Questions about education, awareness, attitude, and behavior.

• Better information about who owns the building and who pays the energy bills.

• Energy consumption data metered in the field and connected to building system characteristics.

• Time-of-use energy consumption data.

• Billing data on a monthly, instead of annual, basis.

• Information about utility rate structures and incentives, along with marginal and average prices at the account level.

Given the wide range of topics that are of interest and would be useful to researchers, it will be important to identify those topics that offer the best balance between value and practicality. That is, the value of new questions to improve end use estimation and provide better information for policy analyses should be weighed against what is feasible and what is within the scope of the existing survey. Some potentially useful data, for example, might require collecting additional technical details about buildings and systems and place an unrealistic burden on both interviewers and respondents. In such cases, however, there may be alternatives for collecting the data. Some data might, for instance, be collected as part of a special study involving energy auditors, and it might be more efficient to collect information on rate structures from the energy utilities rather than from the sample buildings. Such options for collecting additional data will be discussed further in subsequent sections.

For data that are best collected from the building respondent, EIA has to evaluate whether adding topics or expanding on the current ones is in line with the mission of the CBECS; if it is decided that it is, then EIA must prioritize the various needs in the context of the data that are currently collected and that perhaps may have become less useful over the years. The need to manage the length of the questionnaire requires that if any new questions are added, some of the old ones must be dropped.

A particular type of data that may be worth exploring is time-of-use data. Given the expected growth in the number of smart meters, it would seem to make sense to add time-of-use data to the CBECS to take advantage of the wealth and accuracy of information that should become available through this technology. Smart meter data could greatly increase analytic capabilities while reducing the burden on respondents and possibly also reducing interviewing costs. Since a variety of complexities are likely to emerge with respect to the collection, handling, and processing of this type of data, including new confidentiality concerns, it is important to begin now to evaluate the consumption surveys’ potential use of this technology. EIA would need to allocate some resources, primarily in the form of staff

time, to assess the options and evaluate procedures for collecting this type of data, but the return on the investment would be substantial.

There are a number of potential approaches to collecting this sort of data. As a first step, EIA should contact suppliers that have smart metering in place to evaluate what level of data frequency is available for what customer groups, and to assess options for accessing the data. Options then could be evaluated for collecting smart meter data from a random sample of the suppliers contacted for a follow-up interview, all suppliers who are contacted for a follow-up interview, or from a random sample of the suppliers for buildings for which interviews were also conducted.

Recommendation CBECS-7: EIA should prepare for the more widespread availability of smart meter data in the future by evaluating potential uses of such data, strategies for collecting them, and ways of addressing new confidentiality challenges.

Another topic that deserves attention is the ongoing rapid change in end uses. As new end uses appear and existing end uses become more widespread, they need to be evaluated periodically for potential inclusion in the CBECS. Conversely, end uses that are becoming obsolete should be dropped from the questionnaire. The CBECS staff has been keeping track of these changes, but it may be helpful to develop a formal process for making such updates. Formalizing the process should require only minimal investment of additional staff time, although pretesting any new questions through cognitive interviews or focus groups is always worthwhile, even if it requires additional resources. When evaluating the data needs related to particular end uses, it is important to keep in mind that miscellaneous end uses—and electronics use in particular—do not vary substantially by climate or geography, which means that collecting meaningful data could be accomplished without having to increase the sample size due to concerns about regional variations.

Recommendation CBECS-8: EIA should develop a process for the periodic review of new energy end uses or end uses that are becoming more widespread in the commercial sector and which may need to be included on the CBECS questionnaire. The process should also identify end uses that are becoming obsolete and that can be removed from the questionnaire.

Given the burden that the questionnaire already imposes on respondents, EIA should evaluate creative alternatives for collecting additional data without increasing the overall burden on all CBECS respondents. One possible way to collect additional details or new topics would be to field two versions of the questionnaire—a short form and a long form. EIA would have to evaluate the optimal distribution of content between the two forms as well as the size of the sample for each, taking into consideration both costs and analytic needs. To complete the evaluation, EIA staff may need input from its data collection contractor on the cost of the different options. One option would be to design a short form that collects only basic information from all buildings in the sample and a long form that collects additional details, further customized by building type, from a subset of the sample. This would mean that for the full sample less information would be available than what is available now, but for a smaller sample more information would be available than what is available now. The question is whether the same amount of resources could be allocated differently to meet different types of analytic needs. It is possible that overall this would satisfy fewer data user needs than the current approach does, but the concept is worth considering in order to place data use requests for additional detail in perspective.

Recommendation CBECS-9: To accommodate data user needs for more detailed information, EIA should evaluate the possibility of administering a short-form and a long-form CBECS questionnaire.

REVISIONS TO THE CBECS SAMPLE DESIGN AND DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES

In this section, we discuss a number of additional changes that could be made to update the CBECS, including revisions aimed at increasing the efficiency of the data collection and at making the survey more useful to researchers and policy makers.

CBECS Sample Design

As discussed above, the CBECS is based on an area probability sample of commercial buildings, supplemented with lists of special buildings. This is a thorough and well-respected method for developing a sampling frame, but it is expensive. The frame is used only once every four years, and updating it for each new round of the survey is costly and imperfect. EIA has tried

a number of updating approaches over the years, and it has found the challenges to be substantial, particularly in terms of deduplication. For the 2007 CBECS, difficulties related to updating the sampling frame contributed to the problems that eventually rendered the data unusable.

Given the challenges associated with developing and maintaining a sampling frame of buildings for the CBECS, it is worth taking a second look at the possibility of using establishments instead of buildings as the primary basis of the sampling frame. Commercial lists of establishments are more readily available than lists of buildings, and it may be possible to integrate these lists into the CBECS sample-development process while preserving the survey’s focus on buildings as the central unit of interest for the data collection. Because establishment surveys are more common than building surveys, the use of establishments as the basis of the sampling frame would allow the CBECS to benefit from procedures, lists, and data that already exist in connection with these data collections.

As a first step in this process, EIA staff time would be required to evaluate the establishment-based list options that are available for use in sampling frame development and to assess their implications for the efficiency of the data collection. The coverage rates associated with relying on establishment-based lists is an important consideration. If it is necessary to rely on more than one list to achieve adequate coverage rates, the issue of deduplication between the sampling frames should receive careful thought, although deduplicating several lists is likely to be less error prone than prior efforts (especially the 2007 sampling frame development) that involved deduplicating an area-based sample and several lists. Cost and timeliness are two other factors that will also have to be assessed in comparison with the current approach. It is likely that there are lessons to be learned from the experience with the 2007 CBECS sample design, and as EIA continues to evaluate that experience the conclusions could underscore the need for a careful evaluation prior to implementing this change as well as for close monitoring of the implementation once the sampling plan is developed. After a careful evaluation, a staggered launch of the fieldwork may be useful to identify and eliminate problems that could emerge. This could involve releasing a small subset of the cases prior to beginning work on the full sample.

Recommendation CBECS-10: EIA should conduct research to evaluate the advantages and costs associated with using an establishment-based list for the CBECS sampling frame.

CBECS Data Collection Procedures

A major part of the expense of any survey is the cost of following up with respondents to complete the interviews, and this is particularly true for in-person data collection. One way to make the process more efficient would be to take advantage of the fact that in the commercial sector there are many establishments with large numbers of buildings across the country (for example, large companies such as McDonald’s or Walmart) and to collect data about these buildings from a centralized location instead of from the individual buildings. This could work especially well if the survey were to be transitioned to an establishment-based frame and multimode data collection, but, even if those changes are not made, EIA staff should carry out a small research project to evaluate the option of contacting the headquarters of major centralized accounts to inquire about collecting as much data as possible from them. The evaluation should determine whether there are centralized accounts that can provide all of the information necessary for the CBECS for all of their buildings in the sample, and assess how much variability can be expected between the accounts in terms of the data available centrally.

Recommendation CBECS-11: To increase CBECS data collection efficiency, EIA should explore the possibility of contacting the headquarters of major centralized accounts and collecting data about all of the buildings in the sample from these centralized sources.

Data from Energy Suppliers

The CBECS includes an energy supplier survey for about half of the CBECS buildings in the sample. The survey is initiated in cases where the energy usage and cost information cannot be obtained through a building interview or if the data obtained through the building interview are flagged as out of the expected range. EIA should research the possibility of working more closely with energy suppliers. Although differences in the ways different energy suppliers keep their records represents a challenge, EIA is already working with a large number of utilities to obtain consumption and cost data for buildings that cannot supply this information. It would be worth evaluating whether the supplier survey could become the first step in the data collection process, with individual building respondents only being asked the remaining questions. By significantly reducing the

burden on building respondents and possibly also improving data quality for the consumption and cost data, procedures and to serve as a source of ideas efficiencies could be gained that could offset the increased effort associated with requesting utility data for more buildings. It is possible that energy suppliers may find it easier to provide a data file with information for all of their customers as opposed to providing information for individual customers that need follow-up because they are in the CBECS sample and were not able to provide the data themselves. If EIA could request data for all of a utility’s customers, and then extract the data for the buildings that are in the sample, this could reduce the burden on the utilities sufficiently to facilitate collaboration.

As part of evaluating the costs and benefits of collecting supplier data before the building interviews, it may also be worth assessing possibilities related to using energy supplier records to assist with building a sampling frame. EIA considered this option early on, but identified a number of challenges, beyond the variability in the ways utility records are kept. For example, in the sample of commercial accounts examined for a feasibility study, about a quarter were not buildings, but other structures (French, 2007). However, if reliance on energy suppliers were to be increased for the data collection, relying more on utilities for the sampling frame development as well could become more cost effective. Another consideration is that establishing a framework for closer collaboration with utilities would also be useful in paving the way for greater reliance on smart meter data.

Recommendation CBECS-12: EIA should evaluate whether working more closely with the energy suppliers of commercial buildings could lead to procedures and to serve as a source of ideas efficiencies in the data collection process.

Auxiliary Data

As face-to-face data collection becomes more expensive, and maintaining high response rates through most traditional modes of interviewing becomes more difficult, the survey research community is becoming increasingly interested in tapping into existing data sources, such as administrative records. The panel understands that EIA has considered the use of administrative records in the past, and the panel also acknowledges that gathering and combining data from a variety of sources can be resource intensive. Nonetheless, it seems inevitable that the CBECS will eventually have to move toward the use of a multimode data collection approach, and the potential of auxiliary data sources should be revisited

periodically as the costs and data quality benefits associated with integrating such sources into the data collection evolve. As more records become available online, it is likely to be increasingly more efficient to use these auxiliary data sources.

A successful integration of auxiliary data sources into the energy consumption surveys could have some important advantages. Given the technical nature of the questions asked, for example, there are concerns about respondents’ ability to provide accurate answers, which lead in turn to concerns about the accuracy and reliability of the data. The data quality could be improved by finding one or more alternatives to self-reports for some of the information collected, such as square footage and intensity of use. Being able to drop some of these questions from the questionnaire would also free up resources that could be allocated to meeting other data user needs by, for instance, using a larger sample size or collecting data about different topics.

Local government databases, such as county property tax databases, are often available online, and some of them include information on square footage and heat sources, albeit based on definitions that are not always consistent with those used by EIA. Some of these databases also include photographs that can provide useful information on building characteristics. There should be regular evaluation of the availability and accuracy of these databases around the country in order to assess what proportion of cases would have associated records that lend themselves to relatively straightforward integration into the CBECS data. For example, knowing the proportion of counties with property tax records that present no major challenges for use would help determine whether it was cost effective to integrate these sources of data into the survey. It will also be important to evaluate how integrating administrative data could affect the data collection timeline, to assure that adding new sources of data does not adversely affect the time required to process and publish the CBECS data.

The panel’s letter report (see Appendix F) contains suggestions for a more comprehensive research plan for evaluating auxiliary sources of data, if funding for this research can be secured. Collaborations with one or more of the Department of Energy’s research labs could be one productive way of pursuing this type of research without putting a strain on EIA staff time. At the minimum, EIA staff members should stay abreast of what potential new sources of building data are available and should monitor trends indicating what data may become available online in the near future.

Recommendation CBECS-13: EIA should conduct an ongoing evaluation of administrative records as potential sources for substantive data for the CBECS.

Energy Audits

EIA has considered hiring professional energy auditors to collect building data instead of relying on interviewers, but it has never had sufficient funding to do it. The 2011 CBECS data collection plan included a small-scale test with both auditors and interviewers collecting data from the same buildings in order to evaluate the differences between the two approaches, but the test was put on hold along with the survey.

The panel considers this an important test to complete because it could have a large number of benefits. Professional energy auditors are trained and certified to assess building energy use, and for observable building characteristics the data collected by them could be treated as the “gold standard” for use in calibrating the responses gathered by interviewers and evaluating the quality of data from other sources, such as administrative records. The data collected by auditors would also be useful for evaluating some of the current back-end procedures, such as data editing or the regression model used to identify outliers and to initiate a supplier follow-up survey.

While hiring professional auditors would cost more than hiring interviewers, these costs should be evaluated in the context of how much it would cost to provide additional training to interviewers. The use of auditors could reduce some other costs as well. For example, it is possible that building respondents may be more willing to trust a professional auditor than a survey interviewer because auditors may be perceived as more highly qualified on the topic and possibly more “legitimate.” Editing costs could drop if the use of auditors helped alleviate some of the privacy concerns on the part of the building respondents, causing them to be more likely to answer some questions that they would have been reluctant to answer before. Respondents might also be more willing to provide access to equipment and areas of the building to professional auditors that interviewers would find difficult to gain access to. If privacy concerns are reduced, this could also reduce the resources needed to follow up with reluctant respondents. Evaluating these factors and their impact on the costs and benefits of involving energy auditors could be accomplished in the form of a small pilot test, which could be an additional task performed by the data collection contractor.

Recommendation CBECS-14: EIA should test the use of professional energy auditors on a small scale to better understand the costs and benefits related to having experts collect data for a subset of the CBECS sample.

Data Collection Instruments

The CBECS questionnaire should be reviewed on a routine basis to make sure that it is not becoming out of date. EIA keeps track of the content of the data collection instruments, but it is also important to develop a formalized process for carrying out a periodic review. This review should be separate in concept from a major redesign, but could be integrated with the periodic review conducted to assess the relevance of end uses measured by the questionnaire (see Recommendation CBECS-8). The resources required for these activities will depend on the research techniques employed, which should be guided by types of changes that are considered.

The techniques used to evaluate the questions could involve examining the distribution of the responses to each of the questions to identify answer options that no longer reflect the distribution of building characteristics of interest as well as answer categories that may have become obsolete. Cognitive interviews could be conducted to better understand how respondents relate to the question and answer options and to evaluate whether updates are needed. The cognitive interviews should also examine the strategies used by respondents to come up with answers to questions that are suspected of being especially difficult to answer and, thus, of possibly producing less accurate data.

When a questionnaire is updated, it is important to take into account the continuity of the time series. The analysis conducted will have to evaluate the implications of any changes in the context of the risks posed by the modification, while at the same time performing the evaluation with an eye on the future and on what content is expected to be most relevant going forward.

As mentioned, one important aspect of the questionnaire review process is the identification of items that have become outdated or are no longer useful enough to warrant inclusion in the CBECS. Some questions must be removed if new questions are to be added.

Recommendation CBECS-15: EIA should invest in periodic reviews of the CBECS questionnaire content and wording. This should be

understood as a routine updating of the instruments, separate from the concept of a major redesign of the survey.

Greater EIA Involvement in the Data Collection Process

While the panel’s understanding is that EIA staff members participate in all interviewer trainings, more active involvement may be necessary to share the study’s goals and communicate how the quality of the data determines its usefulness. Furthermore, EIA staff members are best qualified to conduct training on any topics and concepts that are complicated due to a long institutional history, such as the definitions of a building and of a qualified respondent. Increased involvement could be accomplished with a minimal investment of time, and the benefits should be noticeable.