Longitudinal Aging Study in India: Vision, Design, Implementation, and Preliminary Findings

P. Arokiasamy, David Bloom, Jinkook Lee, Kevin Feeney, and Marija Ozolins

FOUNDATIONS FOR THE LONGITUDINAL AGING STUDY IN INDIA1

The Context: Global Population Aging

Population aging is a global phenomenon that all countries face, but global averages can mask considerable heterogeneity both across and within regions (Bloom, 2011a). Countries are at various stages of the process: The share of the 60+ population ranges from under 5% in a number of African and Gulf countries to more than 20% in several European and East Asian countries.2 However, there is much less heterogeneity with respect to time trends; population aging will take place in all regions and countries going forward.

These trends have given rise to increased public thinking and dialogue on the issue of population aging. Some researchers suggest that population aging has substantial capacity to diminish the productive

____________

1 An early version of this chapter was presented as a paper in March 2011 at the Indian National Science Academy in New Delhi, India, at a conference on “Aging in Asia.” The authors are indebted to the conference participants and to Paul Kowal and Larry Rosenberg for helpful comments. A more detailed analysis of these data is available at http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/pgda/WorkingPapers/2011/PGDA_WP_82.pdf. This research has been supported by NIA Grants R21AG032572 and P30AG024409 and by a grant from the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University.

2 Except where stated otherwise, international demographic data in this report are derived from United Nations (2011).

capacities of national economies. Other studies suggest that any negative effects on economic growth are likely to be no more than modest (Bloom, Canning, and Fink, 2010; Boersch-Supan and Ludwig, 2010). Regardless of the effect on the economy as a whole, population aging will lead to increased need for elder care and support, at a time when, in developing societies, traditional family-based care is becoming less the norm than in the past. In addition, a higher share of older people will affect budget expenditures (less for education, but more for healthcare) and may affect tax rates.

Population Aging in India: Trends and Challenges

With 1.21 billion inhabitants counted in its 2011 census (Registrar General of India, Census of India, 2011), India is the second most populous country in the world. Currently, the 60+ population accounts for 8% of India’s population, translating into roughly 93 million people. By 2050, the share of the 60+ population is projected to climb to 19%, or approximately 323 million people. The elderly dependency ratio (the number of people aged 60 and older per person aged 15 to 59) will rise dramatically from 0.12 to 0.31. At the same time, India’s older population will be subject to a higher rate of noncommunicable diseases, a higher share of women in the workforce (thus less able to care for the elderly), children who are less likely to live near their parents, and a lack of policies and institutions to deal effectively with these issues (Bloom, 2011b).3

Several forces are driving India’s changing age structure, including an upward trend in life expectancy and falling fertility. An Indian born in 1950 could expect to live for 37 years, whereas today India’s life expectancy at birth has risen to 65 years; by 2050 it is projected to increase to 74 years. Fertility rates in India have declined sharply, from nearly 6 children per woman in 1950 to 2.6 children per woman in 2010. India has also been experiencing a breakdown of the traditional extended family structure; currently, India’s older people are largely cared for privately, but these family networks are coming under stress from a variety of sources (Bloom et al., 2010; Pal, 2007).

India is in the early stages of establishing government programs to support its aging population. At the current burden of disease levels, rising numbers of older people will likely increase demands on the health system (Yip and Mahal, 2008). Less than 10% of the population has health insurance (either public or private), and roughly 72% of healthcare spending is

____________

3 James (2011) points out that the history of long-term population predictions for India has been marked by major inaccuracies.

out-of-pocket. The aging population is particularly at risk, as the health insurance scheme for the poor covers only those aged 65 or younger.

Older Indians also face economic insecurity; 90% of them have no pension. According to official statistics, labor force participation remains high (39%) among those aged 60 and older and is especially high (45%) in rural areas (see Alam, 2004, and Registrar General, 2001). These high participation rates reflect an overwhelming reliance on the agriculture and informal sectors, which account for more than 90% of all employment in India. They also reflect the inadequacy of existing social safety nets for older people (Bloom et al., 2010). In addition, more than two-thirds of India’s elderly live in rural areas, limiting their access to modern financial institutions and instruments such as banks and insurance schemes.

With India in the early stages of a transition to an older society, little is known about the economic, social, and public health implications. Data on the status of older people are needed to analyze population aging and formulate mid- and long-term policies. The Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) is an effort to fill this gap through a large-scale, nationally representative, longitudinal survey on aging, health, and retirement. LASI’s longitudinal character is key: Over an extended period, researchers can assemble a data set that shows the changes in India’s older population and, at the same time, have access to up-to-date data. The survey results and subsequent data analyses will be disseminated to the research community and policymakers.

LASI joins several existing sister surveys of the seminal Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a longitudinal survey of Americans aged 50 and older conducted by the Institute for Social Research (ISR) at the University of Michigan and supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA). HRS has inspired similar studies outside the United States; current and planned HRS-type studies cover more than 25 countries on four continents (Lee, 2010). One striking feature of the HRS-type surveys is the possibility of pooling data from different countries to assess the effects of differing institutions on behavior and outcomes. Taken as a whole, the HRS family offers many opportunities to widen and deepen research on the nature and implications of aging.4

____________

4 Another source of valuable micro-data on older populations is the Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health, or SAGE, developed by the World Health Organization MultiCountry Studies Unit. SAGE covers six countries (China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russian Federation, and South Africa), and while focused on those aged 50+, includes a small sample of adults aged 18-49 years. It has more focus on health and less on economic and financial data than the HRS family of surveys.

LONGITUDINAL AGING STUDY IN INDIA (LASI)

Design and Vision

In this section of the chapter, we discuss the design and sampling frame for the LASI pilot, highlighting features that allow researchers to begin to identify and answer important questions about population aging in India. We also evaluate the validity of the fieldwork by comparing the LASI pilot sample to that of other surveys in India.

India, like other countries in which HRS-style surveys have been conducted, presents a unique set of challenges. Income and assets, for example, are difficult to measure due to lack of written documentation and the fact that a significant portion of income and production does not take place in market contexts. In addition, people may be disinclined to reveal certain information (e.g., some women may be reluctant to reveal that they have savings balances for fear that their husbands or sons-in-law will claim them).

To capture India’s demographic, economic, health, and cultural diversity, the LASI pilot focused on two northern states (Punjab and Rajasthan) and two southern states (Karnataka and Kerala). Rajasthan and Karnataka provide some overlap with the World Health Organization’s Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE). Punjab is an economically developed state, while Rajasthan is relatively poor. Kerala, known for its relatively developed healthcare system, has undergone rapid social development and is a potential harbinger of how other Indian states might evolve (Pal and Palacios, 2008). The LASI instrument was developed in English and translated into the dominant local languages: Hindi (Punjab and Rajasthan), Kannada (Karnataka), and Malayalam (Kerala).

The LASI questionnaire was also designed to collect information conceptually comparable to related HRS surveys and SAGE.5 The instrument consists of a household survey, collected once per household by interviewing a selected key informant about household finances and living conditions for those in the household; an individual survey, collected for each age-eligible respondent at least 45 years of age and their spouse (regardless of age); and a biomarker module, collected for each consenting age-eligible respondent and spouse.

The household interview consists of five sections: a roster detailing basic demographic information about each household member; a ques-

____________

5 These include the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) in the United States, the English Longitudinal Survey of Ageing (ELSA), the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS), the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS), the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA), the Japanese Study of Aging and Retirement (JSTAR), and the Study of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), which covers 15 European countries.

tionnaire about the housing and neighborhood environment, including questions about access to water, neighborhood conditions, and other attributes; income of all family members from labor and nonlabor sources; assets and debts of the household; and consumption and expenditure of the household on food and nonfood items, including items that were exchanged in-kind, gifted, or home-grown.

The individual interview consists of seven sections: demographics, family and social networks, health, healthcare utilization, work and employment, pension and retirement, and one experimental section.6 An important component of the health section is a biomarker module collected by the interview team. Given the lack of healthcare services, biological markers (e.g., anthropometrics, blood pressure, and dried blood spots) and performance measures (e.g., gait speed, grip strength, balance, lung function, and vision) allow researchers to assess the health of LASI’s sample population. The dried blood spot collection, for example, allows for up to 35 different assays, including four that the LASI team initially plans to test: C-reactive protein (CRP, a marker of inflammation), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c, a marker of glucose metabolism), hemoglobin (Hb, a marker of anemia), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibodies (a marker of cell-mediated immune function).

Sampling Plan, Fieldwork, and Administration

Funded by the National Institute on Aging, LASI is a partnership between the Harvard School of Public Health, the International Institute for Population Sciences in Mumbai, India, and the RAND Corporation. Also involved in LASI are two other Indian institutions, the National AIDS Research Institute (NARI) and the Indian Academy of Geriatrics (IAG). The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Medicine is also a participant in LASI.

The fieldwork was carried out by a network of Population Research Centers (see Table 3-1). Fieldwork lasted from October to December 2010. The rapid turnaround from data collection to the analysis of the data was possible through use of state-of-the-art technology in data management and computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI).

Using the 2001 Indian Census,7 we drew a representative sample from the four states. Age-qualifying individuals were drawn from a stratified,

____________

6 The experimental section consists of a module of questions on one of the following three topics, randomly assigned: economic expectations, anchoring vignettes, and social connectedness.

7 The Indian Census is conducted every 10 years. The 2011 wave was recently released, so the first full LASI wave will be able to utilize the latest population sample during fieldwork.

TABLE 3-1 Administration of the 2010 LASI Pilot Survey

| Karnataka | Kerala | Punjab | Rajasthan | ||

| Timeline | |||||

| From | 29 October | 1 November | 14 November | 14 November | |

| To | 3 December | 14 December | 12 December | 18 December | |

| Organization | |||||

| Population Research Centre, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore | Population Research Centre, Department of Demography, University of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram | Population Research Centre, Department of Economics, Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla | Population Research Centre, Department of Economics, University of Lucknow, Lucknow | ||

NOTE: LASI fieldwork was planned in order to avoid monsoon season, which typically lasts from June to September.

multistage, area probability sampling design, beginning with census community tracts. From each state, two districts were selected at random from Census districts for 2001; eight primary sampling units (PSUs) were randomly selected from each district. PSUs were chosen to match the urban/rural share of the population. Twenty-five residential households were then selected through systematic random sampling from each PSU, from which an average of 16 households contained at least one age-eligible individual.

The LASI pilot achieved a household response rate of 88.5%, calculated as the ratio of consenting to eligible households (as further adjusted for cases of no contact, missing eligibility information, or refusal to give eligibility information; see Table 3-2). The individual response rate (90.9%) and biomarker module response rate (89%) were calculated conditional on belonging to a household that consented to participate in the LASI interview. Eligible households were defined as those with at least one member 45 years of age and older, and eligible individuals were those who were 45 years of age and older or married to an individual who was.8

____________

8 Eligible age for response rates was determined from the coverscreen household roster, which was reported by the household respondent, who was not always an individual respondent. The respondent who consented to the individual interview did self-report age in the demographics component of the module, effectively creating two possible age variables. On occasion, some individuals who were listed as 45 years of age and older reported they were not or vice versa in the individual interview. For consistency, we calculate the response rates using ages reported in the coverscreen, though for the remaining analysis presented in the paper we rely on self-reported age. The results of all models were not sensitive to the age variable used.

TABLE 3-2 LASI Pilot Study, Response Rate

| Urban | Rural | Punjab | Rajasthan | Kerala | Karnataka | Total | |

| Household Survey | |||||||

| Sampled | 485 | 1,062 | 375 | 371 | 395 | 406 | 1,547 |

| Unable to contact | 10 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 6 | 23 |

| Contact established | 475 | 1049 | 375 | 371 | 378 | 400 | 1,524 |

|

Age eligible |

325 | 756 | 254 | 255 | 297 | 275 | 1,081 |

|

Not eligible |

140 | 284 | 120 | 114 | 70 | 120 | 424 |

|

Unknown eligibility |

10 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 19 |

| Did not start interview | 31 | 56 | 28 | 13 | 24 | 22 | 87 |

| Started interview | 294 | 700 | 226 | 242 | 273 | 253 | 994 |

| Completed interview | 281 | 669 | 222 | 230 | 261 | 237 | 950 |

| Household Response Rate (%) | 85.2 | 90.0 | 88.6 | 94.2 | 84.0 | 88.5 | 88.5 |

| Individual Survey | |||||||

| Total eligible | 567 | 1,359 | 419 | 485 | 559 | 463 | 1,926 |

|

Age eligible |

505 | 1,201 | 385 | 423 | 506 | 392 | 1,706 |

|

Spouse eligible |

62 | 158 | 35 | 61 | 53 | 71 | 220 |

| Started individual interview | 492 | 1,259 | 410 | 436 | 483 | 422 | 1,751 |

|

Age eligible |

439 | 1,109 | 375 | 380 | 436 | 357 | 1,548 |

|

Spouse eligible |

53 | 150 | 35 | 56 | 47 | 65 | 203 |

| Completed individual interview | 472 | 1,211 | 402 | 417 | 462 | 402 | 1,683 |

|

Age eligible |

419 | 1,067 | 368 | 363 | 418 | 337 | 1,486 |

|

Spouse eligible |

53 | 144 | 34 | 54 | 44 | 65 | 197 |

| Individual Response Rate (%) | 86.8 | 92.6 | 97.9 | 89.9 | 86.4 | 91.1 | 90.9 |

| Biomarker Module | |||||||

| Total eligible | 567 | 1359 | 419 | 485 | 559 | 463 | 1,926 |

| Consented to start biomarker module | 474 | 1241 | 398 | 436 | 480 | 401 | 1,715 |

| Biomarker Response Rate (%) | 83.6 | 91.3 | 95.0 | 89.9 | 85.9 | 86.6 | 89.0 |

| Response Rates for Selected Questions (%) | |||||||

|

Dried blood spot collection (biomarker module) |

64.6 | 77.5 | 76.4 | 75.8 | 69.6 | 76.5 | 74.3 |

|

Satisfaction with spousal relationship (family and social networks) |

93.4 | 93.9 | 97.3 | 90.6 | 89.0 | 99.7 | 93.8 |

|

Income (household questionnaire) |

77.2 | 79.2 | 77.9 | 73.5 | 85.1 | 77.2 | 78.6 |

|

Consumption (household questionnaire) |

79.4 | 82.8 | 92.3 | 73.9 | 80.8 | 80.6 | 81.8 |

|

“Probability” respondent will die in one year (expectations module) |

87.3 | 88.0 | 94.7 | 89.1 | 71.6 | 98.5 | 87.8 |

NOTES: Response rates are calculated by dividing the total number of individuals or households who consented to the interview by the total number of contacted, eligible individuals (including spouses under 45 years of age) or households as reported in the coverscreen household component of the interview. Households that were not contacted indicate cases when the interviewing team was unable to speak with an individual residing at the house either because no one was home, the family has moved, or for some other reason. Five contact attempts were suggested before classifying a household as “no contact.” The household response rate across all states is thus calculated by dividing 994 households that initially consented by the sum of the number of no contacts (23), the contacted eligible households (1,081), and the 19 households with missing or refused age eligibility. Note that this reflects a conservative estimate to the response rate. The individual response rate across all states is calculated by dividing the 1,751 individuals who consented to start the individual interview by the 1,926 eligible household members listed in the coverscreen of the household roster once the survey began. Response rates for select questions pertain to respondents who were asked that specific question, not the total eligible persons listed in the coverscreen. This approach was chosen to best capture the effects of the sensitive nature of the questions. Thus the dried blood spot collection response rate captures the share of respondents who specifically agreed to participate. Response rates for income and consumption are among households and are the share of households that did not require imputation and had no missing income components queried about during the household module. The probability respondents will die in one year is a question from the expectations module, one of three experimental modules that was randomly assigned to respondents at the end of the individual interview. The question asked respondents to select a number of beans from a pile of 10 beans to indicate how likely they were to die in the next year. Response rates for more standard survey questions were 98% and above; response rates of selected questions were chosen to showcase survey items with lower response rates.

SOURCE: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

Among households and individuals who consented to start the LASI interview, not all individual or household modules were completed after initial consent was given. Table 3-2 tabulates the number of respondents and households that completed an individual or household interview; these 950 households and 1,683 individuals constitute the complete LASI pilot sample. Of the 1,683 individuals who completed an individual interview, 1,486 respondents9 were aged 45 years and older. The 197 who were not age-eligible were female spouses of age-qualifying participants.

Table 3-2 also shows relatively high response rates to selected potentially sensitive questions.

We observed significant heterogeneity in the length of time to complete the survey across states, from a total time of 137 minutes in Rajasthan and Karnataka to a high of 215 minutes in Punjab (see Table 3-3). Some interviews were split over time: about 15% of the interviews occurred over a span of two or more days.10

The average duration of the household module was 33 minutes. For the individual interview, including the biomarker module, the mean duration was 78 minutes. Households had a mean of 1.8 respondents who completed individual interviews.

Profile of LASI Respondents

The LASI design and implementation was successful in creating a sample comparable to other nationally representative surveys conducted in India. In Table 3-4, we present the initial results of the fieldwork through a comparison of the basic demographic indicators of LASI respondents to those of respondents from other surveys conducted in India: the National Sample Survey (NSS), India Human Development Survey (IHDS), World Health Survey (WHS), and SAGE. As the other surveys have broader age inclusion categories, we restrict the comparison to individuals aged 45 and older only.

We compare the distribution of demographic characteristics for those aged 45 and older across the four surveys, looking specifically at age, sex, urban-rural residence, marital status, and education. We expect some differences across these metrics, given the different sets of states surveyed. For example, LASI has a comparatively small sample size from four

____________

9 Of the 1,486 respondents who were identified in the coverscreen as being aged 45 and older, 1,451 confirmed that status in the individual interview. We use these 1,451 as our analysis sample. The remaining 232 respondents consists of 230 who self-reported their age as less than 45 (of which 181 were also identified as less than age 45 in the coverscreen), and 2 who did not report an age. These 232 individuals were not included in the analysis sample.

10 Such a span took place when at some point during the interview, the interview team was asked to leave and come back on a different day.

TABLE 3-3 Average Survey Duration by State of Key Survey Components (in minutes)

| Punjab | Rajasthan | Kerala | Karnataka | All States | |

| Total Time at Household (HH) | 215.2 | 137.3 | 205.2 | 137.4 | 174.7 |

| Household Module | |||||

| Total | 41.9 | 29.1 | 37.6 | 24.6 | 33.4 |

| Housing and environment | 9.2 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 5.3 | 7.2 |

| Consumption | 12.3 | 7.6 | 13.1 | 7.3 | 10.1 |

| Income | 7.9 | 5.0 | 7.4 | 5.2 | 6.4 |

| Agricultural income and assets | 3.9 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| Financial assets and real estate | 8.6 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 4.8 | 6.8 |

| Number of interviews | 222 | 230 | 261 | 237 | 950 |

| Individual Module | |||||

| Total | 93.9 | 57.8 | 92.5 | 66.5 | 78.1 |

| Demographics | 9.5 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 6.9 |

| Family and social network | 15.0 | 11.2 | 13.1 | 8.9 | 12.1 |

| Health | 27.4 | 17.2 | 30.5 | 15.9 | 23.0 |

| Healthcare utilization | 4.7 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 3.8 |

| Employment | 7.2 | 2.5 | 7.3 | 4.8 | 5.5 |

| Pension | 4.2 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| Experimental: social connectedness |

11.3 | 4.9 | 10.0 | 7.6 | 8.4 |

| Experimental: expectations | 5.9 | 3.5 | 6.2 | 3.0 | 4.7 |

| Experimental: vignettes | 4.8 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 3.1 |

| Biomarker | 18.9 | 14.2 | 21.0 | 22.3 | 19.1 |

| Number of interviews | 402 | 417 | 462 | 402 | 1,683 |

|

Number of individual interviews per HH |

1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| Duration of Interviews | |||||

| One day (n) | 298 | 338 | 390 | 380 | 1,406 |

| Multiple days (n) | 103 | 74 | 61 | 20 | 258 |

|

Interviews lasting multiple days (%) |

25.7 | 18.0 | 13.5 | 5.0 | 15.5 |

NOTE: Total time at HH is the average time spent at a household, including the time spent conducting the household module and all individual modules (including the biomarker module).

SOURCE: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

TABLE 3-4 External Validity: Comparison of LASI to Other Surveys on Select Demographic Indicators

| All States in Sample | Rajasthan | Karnataka | |||||||||||||||

| LASI | NSS | IHDS | WHS | SAGE | LASI | SAGE | LASI | SAGE | |||||||||

| Survey year(s) | 2010 | 2004 | 2004-05 | 2003 | 2007-08 | 2010 | 2007-08 | 2010 | 2007-08 | ||||||||

| Total number of individuals | 1,683 | 383,338 | 215,754 | 10,750 | 12,198 | 417 | 2,374 | 402 | 1,744 | ||||||||

| Number of individuals aged 45+ | 1,451 | 81,146 | 45,074 | 3,706 | 7,841 | 358 | 1,587 | 315 | 1,139 | ||||||||

| Age structure (%) Among Respondents 45 Years and Older | |||||||||||||||||

| Age 45-54 | 44.3 | 44.1 | 44.9 | 41.7 | 48.7 | 43.1 | 49.9 | 49.5 | 52.3 | ||||||||

| Age 55-64 | 28.4 | 32.7 | 29.7 | 26.1 | 28.3 | 23.4 | 26.9 | 31.8 | 25.8 | ||||||||

| Age 65-74 | 17.8 | 17.4 | 17.9 | 18.1 | 16.4 | 21.8 | 16.3 | 14.0 | 15.2 | ||||||||

| Age 75+ | 9.5 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 14.1 | 6.7 | 11.8 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 6.8 | ||||||||

| Sex (%) Among Respondents 45 Years and Older | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 48.7 | 50.5 | 51.4 | 50.7 | 55.2 | 51.5 | 53.7 | 47.6 | 56.6 | ||||||||

| Female | 51.3 | 49.5 | 48.6 | 49.4 | 44.8 | 48.5 | 46.3 | 52.4 | 43.5 | ||||||||

| Residence (%) Among Respondents 45 Years and Older | |||||||||||||||||

| Urban | 27.1 | 26.3 | 26.9 | 11.1 | 26.8 | 19.2 | 20.5 | 35.7 | 32.3 | ||||||||

| Rural | 72.9 | 73.8 | 73.1 | 88.9 | 73.2 | 80.8 | 79.5 | 64.3 | 67.7 | ||||||||

| Marital Status (%) Among Respondents 45 Years and Older | |||||||||||||||||

| Married | 78.0 | 75.8 | 78.2 | 80.7 | 81.5 | 81.0 | 81.5 | 75.3 | 82.4 | ||||||||

| Never married | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| Divorced | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | ||||||||

| Widowed | 19.1 | 22.5 | 20.6 | 17.3 | 17.3 | 16.8 | 17.5 | 21.9 | 16.7 | ||||||||

| Education (%) Among Respondents 45 Years and Older | |||||||||

| No education | 48.2 | 58.6 | 53.2 | 63.4 | 47.6 | 79.1 | 62.7 | 42.6 | 48.1 |

| < 5 years | 8.1 | 8.6 | 10.7 | 11.2 | 13.2 | 3.3 | 9.3 | 12.9 | 14.2 |

| 5-9 years | 22.0 | 19.5 | 21.0 | 15.0 | 19.8 | 8.3 | 15.2 | 23.6 | 17.5 |

| 10+ years | 21.7 | 13.4 | 15.1 | 10.5 | 19.4 | 9.2 | 12.7 | 20.9 | 20.2 |

NOTES: For this table, we use the 1,451 respondents who self-reported age of at least 45 years in the individual interview. LASI is the Longitudinal Study of Aging in India, NSS is the National Sample Survey, IHDS is the Indian Human Development Survey, WHS is the World Health Survey, and SAGE is the Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health. SAGE states include Assam, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. NSS is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey of all Indian states conducted by the Indian government’s Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. IHDS is a nationally representative survey among 33 states and territories conducted between 2004 and 2005 to assess the health of all household members, with special questions to assess children’s well-being. It is conducted by the University of Maryland. WHS is a nationally representative survey conducted by the World Health Organization and was later reorganized as SAGE survey to target aging populations and produce harmonized survey data with parallel efforts in Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.

SOURCES: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (2004), Indian Human Development Survey (2005), and World Health Organization (2003, 2010).

diverse states, including Kerala, which is exceptional because of the relatively high level of educational attainment among the population. This is reflected in Table 4-4: 22% of the LASI sample report having some high school or more for their education, which is higher than the other data sets. With respect to this indicator, LASI is most comparable to SAGE (19%), which likely reflects the overlap in state coverage.

Table 3-4 takes a closer look at the LASI pilot and SAGE results. The SAGE states of Karnataka and Rajasthan were included in the LASI pilot in part to measure the validity of the LASI sample against a more established survey, so we examine the validity of these states’ samples separately. In these two states we again see similar respondent populations, despite the small sample sizes in the LASI pilot. The LASI sample in Rajasthan was slightly older than that of SAGE, while in Karnataka the sample was slightly younger. LASI surveyed proportionally more women from Karnataka than did SAGE. The differences in education and marital status are negligible.

In making cross-state comparisons, it should be kept in mind that each state’s sample is drawn from a relatively small number of districts. As such, the state comparisons referred to herein reflect district-specific idiosyncrasies, in addition to more pervasive state characteristics. Nevertheless, most of the state-by-state comparisons accord reasonably well with independent data and perceptions.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM LASI?

Characteristics of India’s Aging Population

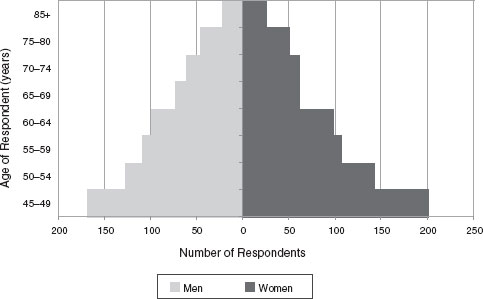

The LASI pilot is able to provide researchers with a picture of life for aging Indians that reflects the significant regional and social variations within the country. Even the most basic demographic indicators—such as education, marital status, and self-rated health—differ not only by gender and socioeconomic status within regions, but also across regions. Table 3-5 displays demographic differences in the representative LASI sample of those aged 45 years and older as self-reported in the demographics module. Men and women both have a mean age of 58, and there is a slightly higher representation of men among rural populations, which make up 70% of the sample overall. Figure 3-1 shows a similar age distribution among men and women, though there are more women than men in the 45-59 group, as well as more women among respondents 85 years and older. Men are also more likely to be married and women more likely to be widowed, an important demographic difference that reflects the traditional age gap between spouses in India. Educational attainment and

TABLE 3-5 Demographic Characteristics by Gender and State in LASI Sample

| Men | Women | Punjab | Rajasthan | Kerala | Karnataka | |

|

N |

706 |

745 |

365 |

358 |

413 |

315 |

|

Age (yrs) |

58.1 |

57.9 |

56.9 |

59.0 |

60.4 |

55.3 |

|

[10.17] |

[11.26] |

[11.07] |

[11.26] |

[10.81] |

[8.86] |

|

|

Rural |

75.7 |

71.8 |

70.6 |

82.4 |

75.8 |

63.9 |

|

[0.41] |

[0.44] |

[0.46] |

[0.33] |

[0.40] |

[0.48] |

|

|

Married |

91.5 |

64.3 |

80.7 |

80.4 |

75.8 |

74.8 |

|

[0.28] |

[0.48] |

[0.39] |

[0.38] |

[0.42] |

[0.43] |

|

|

Widowed |

6.3 |

31.9 |

18.4 |

17.2 |

18.9 |

22.6 |

|

[0.24] |

[0.46] |

[0.39] |

[0.36] |

[0.38] |

[0.42] |

|

|

Household size (no. of people) |

5.3 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

6.5 |

4.4 |

4.9 |

|

|

[2.71] |

[2.97] |

[2.93] |

[2.88] |

[2.05] |

[2.84] |

|

Scheduled caste |

13.8 |

15.1 |

34.5 |

10.0 |

7.0 |

17.0 |

|

[0.34] |

[0.36] |

[0.48] |

[0.28] |

[0.24] |

[0.38] |

|

|

Scheduled tribe |

15.4 |

13.3 |

0.0 |

36.3 |

0.0 |

8.8 |

|

[0.36] |

[0.34] |

— |

[0.47] |

— |

[0.28] |

|

|

Other backward |

38.4 |

39.4 |

9.7 |

27.9 |

42.5 |

60.6 |

|

caste |

[0.48] |

[0.48] |

[0.30] |

[0.44] |

[0.49] |

[0.49] |

|

None/other caste or tribe |

32.5 |

32.1 |

55.8 |

25.8 |

50.5 |

13.6 |

|

|

[0.46] |

[0.46] |

[0.50] |

[0.42] |

[0.49] |

[0.34] |

|

Hindu |

75.6 |

75.7 |

30.2 |

84.6 |

71.1 |

89.6 |

|

[0.42] |

[0.43] |

[0.46] |

[0.34] |

[0.44] |

[0.31] |

|

|

Muslim |

7.9 |

8.1 |

0.0 |

15.1 |

4.5 |

6.7 |

|

[0.26] |

[0.27] |

— |

[0.34] |

[0.21] |

[0.25] |

|

|

Christian |

6.1 |

7.6 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

24.4 |

2.6 |

|

[0.24] |

[0.26] |

[0.10] |

— |

[0.41] |

[0.16] |

|

|

Sikh |

8.2 |

7.4 |

60.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

[0.28] |

[0.26] |

[0.49] |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

Other religion |

1.8 |

1.3 |

8.6 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

1.1 |

|

[0.13] |

[0.11] |

[0.28] |

[0.06] |

[0.00] |

[0.10] |

|

|

Education (yrs) |

5.1 |

3.4 |

3.3 |

1.7 |

7.7 |

4.4 |

|

[5.10] |

[4.43] |

[4.45] |

[3.65] |

[3.70] |

[4.79] |

|

|

Literate |

57.4 |

40.7 |

41.4 |

18.7 |

88.3 |

51.4 |

|

[0.49] |

[0.49] |

[0.49] |

[0.37] |

[0.31] |

[0.50] |

|

|

Labor force participation |

71.3 |

26.2 |

47.1 |

55.7 |

32.9 |

53.8 |

|

[0.45] |

[0.44] |

[0.50] |

[0.48] |

[0.46] |

[0.50] |

|

|

Per capita income (Rs) |

41,752 |

42,123 |

53,888 |

31,354 |

68,930 |

25,272 |

|

|

[92,649] |

[84,883] |

[85,304] |

[77,059] |

[125,534] |

[44,460] |

|

Self-rated health |

3.3 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

2.8 |

3.5 |

|

[0.80] |

[0.80] |

[0.78] |

[0.85] |

[0.72] |

[0.64] |

|

|

Poor or fair self-rated health |

12.3 |

15.7 |

12.3 |

14.5 |

24.3 |

5.4 |

|

|

[0.32] |

[0.36] |

[0.33] |

[0.34] |

[0.42] |

[0.23] |

NOTES: This table only considers respondents who self-reported an age of at least 45 years in the individual interview and provided an answer for each of the variables listed in the table. All numbers are reported as a percentage unless otherwise noted; standard deviations

are reported in brackets. LASI used a stratified sampling design that sampled respondents independently by state, rural-urban areas, and district. Means are weighted using either the pooled-state weight or the state-specific weight, and the standard errors have been corrected for design effects of stratification. Labor force participation is a dummy variable for having worked in the past 12 months. It includes self-employment, employment by another, or agricultural work both paid and unpaid as reported in the household income module by a household financial respondent or as self-reported in the individual interview. Self-rated health asks respondents whether they feel their health in general is excellent (scored 5), very good (4), good (3), fair (2), or poor (1).

SOURCE: Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

FIGURE 3-1 Population pyramid for LASI respondents.

NOTE: Among respondents aged 45 years and older only.

SOURCE: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

literacy are also higher for men than women, although with considerable heterogeneity across states.

Economic activity also differs by gender; 69% of men report working in the past year in either agricultural labor, for an employer, or self-employed work, compared to less than one-quarter of women. Men tended also to have better self-rated health than women, and women were more likely to report poor or fair self-rated health. Generally, women in the sample were more likely to be widowed, less educated, have lower self-rated health, and to be not working, which is consistent with literature on India and other surveys.

Table 3-5 also shows some important interstate differences across the LASI sample. Kerala has an older sample, with a mean age of 60, while Karnataka, the other southern state in the LASI sample, has a comparatively young population (with a mean age of 56) compared to the other three states. Rajasthan tends to be more rural than the other states and Karnataka the least rural. Family demographics, such as household size and marital status, vary as well.

The distribution of caste, tribe, and religion across the four states reflects the regional and sociocultural variation that LASI has been able to capture. About one-third of the Rajasthan sample identifies itself as members of a scheduled tribe, while in Punjab, almost 60% of the population does not identify itself as a scheduled tribe, scheduled caste, or other backward caste. Each state also reflects the diversity in religious belief systems in India—the large Sikh population in Punjab and the sizable Christian population in Kerala, in addition to Hindus and Muslims that make up most of Karnataka and Rajasthan.

These four states reflect different patterns of social and economic well-being. For example, Kerala’s population has comparatively high educational attainment, attributable to a legacy of social development programs. Respondents from Kerala are older and report relatively low labor force participation and worse health than respondents from the other states. The higher prevalence of poor or fair self-rated health may indeed reflect high morbidity in the population, but high literacy rates and better access to healthcare services than in other Indian states also contribute to a more health-literate population (Bloom, 2005). Conversely, Rajasthan, the poorest state in the sample, has the lowest mean years of education, at just below two years, yet the highest labor force participation, at 56%. This reflects the rural-based subsistence economy that requires all household members to engage in some work, even at older ages.

Basic Living Conditions of Older People in India

While economic growth has been rapid, basic living conditions for many Indians, especially the aging, are still poor (Husain and Ghosh, 2011; Pal and Palacios, 2008). Table 3-6 reports indicators of hardship and vulnerability among the LASI pilot sample aged 45 and older, looking specifically at such indicators as drinking water, sanitation, basic household utilities, health, and food security. These are common markers used in the development literature to assess quality of life (Ahmed et al., 1991; Clark and Ning, 2007).

Table 3-6 shows that almost 80% of LASI respondents live in households that do not have access to running water in the home, and 45% do not have access to an “improved water source.” Sixty percent live in

TABLE 3-6 Select Indicators of Hardship and Vulnerability by State Among Individuals 45 Years and Older

| Punjab | Rajasthan | Kerala | Karnataka | All States | |

| Household | |||||

| N | 222 | 230 | 261 | 237 | 950 |

|

Basic utilities |

|||||

|

No electricity in home |

3.5 | 42.6 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 15.0 |

|

No running water in home |

40.7 | 86.3 | 94.8 | 74.3 | 78.6 |

|

No access to improved water source |

2.2 | 68.9 | 79.8 | 10.7 | 44.5 |

|

No private toilet facility |

10.1 | 67.8 | 0.3 | 42.0 | 35.8 |

|

No access to improved sewerage disposal |

48.7 | 88.1 | 5.7 | 75.2 | 59.0 |

|

Does not use good quality cooking fuel |

31.0 | 88.0 | 52.4 | 43.5 | 57.9 |

|

No refrigerator in home |

33.7 | 93.2 | 48.0 | 87.1 | 72.6 |

| Individual | |||||

| N | 365 | 358 | 413 | 315 | 1,451 |

|

Living alone |

10.8 | 6.4 | 17.3 | 16.7 | 12.8 |

|

Illiterate |

61.4 | 79.7 | 11.1 | 46.5 | 50.3 |

|

Health insurance* |

0.5 | 0.8 | 12.2 | 6.8 | 5.7 |

|

Difficulty with at least 1 ADL |

9.5 | 7.0 | 20.1 | 14.1 | 12.7 |

|

Undiagnosed hypertension |

39.5 | 40.9 | 19.4 | 27.6 | 31.3 |

|

Urban |

37.1 | 39.1 | 19.3 | 36.4 | 33.4 |

|

Rural |

40.2 | 41.1 | 19.8 | 22.6 | 30.6 |

|

Men |

46.0 | 38.5 | 19.7 | 26.1 | 31.5 |

|

Women |

32.7 | 43.0 | 19.6 | 28.8 | 31.2 |

|

Under age 60 |

39.4 | 39.6 | 20.0 | 20.4 | 28.6 |

|

Age 60 and older |

39.2 | 42.1 | 19.3 | 42.1 | 35.2 |

| Food insecurity (past 12 months) | 4.2 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 12.2 | 41.1 | 13.4 | 28.3 | 26.7 |

*Of the respondents aged 45 and older who said they did not have health insurance, 46% said they did not have it because they did not know what it is (have never heard of it); 23% said they could not afford it; 16% did not feel that they needed it; 7% did not know where to purchase it; 3% reported being denied health insurance and 5% listed some other reason for not obtaining health insurance.

NOTES: All numbers are percentages. The sample is restricted to respondents who reported they were at least 45 years old in the individual interview and provided a nonmissing answer for each of the variables listed in the table, with the exception of hypertension variables. Hypertension prevalence was calculated only among respondents in the biomarker module. Improved water source includes piped water, tube well, and protected dug well. Sources of water not considered improved are unprotected wells, water from springs/rainwater/surface water, and tanker trucks. Access to improved sewage disposal includes piped sewer system or septic tanks. Dry toilets, pit latrines, or no facility are not included. Good quality cooking fuel includes coal, charcoal, natural gas, petroleum, kerosene, or electric. Activities of daily life (ADL) include using a toilet, bathing, dressing, eating, walking across a room, and getting out of bed. Undiagnosed hypertension is among all respondents,

whether hypertensive or not. It is a binary indicator if hypertension is indicated from the biomarker module but the respondent reports never having received a diagnosis for high blood pressure or hypertension from a health professional. Lee et al. (2012) includes an in-depth analysis of undiagnosed hypertension. Living alone is defined as living with one’s self only or with one’s spouse only (Dandekar, 1996). The surprisingly high figures for Kerala for lack of access to improved water sources and for not having running water in the home are consistent with other relevant reports about Kerala, e.g., International Institute for Population Sciences and Macro International (2007). Food insecurity is a binary indicator for respondents who report having lost weight due to hunger, not eaten for a whole day or gone hungry because there was not enough money to buy food, or otherwise reduced the size or frequency of meals because there was not enough money to buy food. Means are weighted using the state-specific or the pooled-state weights.

SOURCE: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

households without proper sewer systems. Nearly 60% also live in households that use poor quality cooking fuel, which can contribute to indoor air pollution (World Bank, 2002). More than 90% of households in Rajasthan use low-quality cooking fuel, compared with just 31% of households in the wealthier, more urbanized state of Punjab. Conditions vary widely across states. In Kerala and Punjab, the great majority of respondents have access to a private toilet facility, while more than 65% of respondents in Rajasthan do not.

Compounding poor living and environmental conditions are health and economic concerns. Thirteen percent reported living alone. Living alone is most common in the southern states of Kerala (17%) and Karnataka (16%) and least common in Rajasthan. An essentially nonexistent health insurance system and high rates of illiteracy also leave aging individuals vulnerable.

Measuring the Health of Aging Indians

LASI relies on a wide spectrum of health measures, ranging from self-reports of general health (“In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”) to queries about specific diagnoses (“Have you ever been diagnosed by a health professional with hypertension?”). Older respondents who are poor, uneducated, and lack access to healthcare may underreport health conditions that do not have severe symptoms. Self-reports by literate populations with better access to health services may more accurately reflect prevalence rates.

To understand the degree to which this bias can affect estimates, we present results in Table 3-6 from LASI’s biomarker module. Specifically, we report the percentage with high blood pressure who reported never

receiving a diagnosis for hypertension by a health professional. Thirty-one percent of the sample population had undiagnosed hypertension. In Rajasthan, 41% of respondents had undiagnosed hypertension, while in Kerala, only half that percentage registered undiagnosed hypertension. The high prevalence points to the sizable incidence of noncommunicable diseases, the burden of conditions that go unrecognized and untreated, as well as the wide disparity in access to health services (Alwan et al., 2010; Mahal, Karan, and Engelgau, 2010).

In addition to measuring health, LASI assessed self-reported disability rates. Disability was measured by difficulty with at least one activity of daily life (ADL) and averaged 13% across all states, with older people in Kerala reporting the most difficulty and those in Rajasthan the least. While there is some doubt about the validity of self-reported health measures (Sen, 2002), other literature has shown that ADLs and measures of disability in particular can be useful in understanding health burdens in this population along with other research that shows self-reported measures are reasonable to use in the developing country context (Subramanian et al., 2009).

Tables 3-7 and 3-8 focus on LASI’s measure of difficulty with ADLs, with particular attention to a well-documented sex gradient (Sengupta and Agree, 2003). Self-reported ADLs have been shown to be good markers for the health status of Indians (Chen and Mahal, 2010). Table 3-7 shows the number of disabilities reported by men and women in LASI. Of those respondents who reported difficulty with ADLs, most reported difficulty with only one or two of the activities. Women more often reported at least one difficulty with an ADL. Among women, the most common difficulties were walking across a room and getting in and out of bed. Men also reported the most difficulty with walking across a room and getting in and out of bed, although at older ages getting dressed and walking across the room were the most common difficulties (see Table 3-8).

Stratifying the associations we observe between sex and disability by age illustrates an even stronger sex disparity in health among aging Indians in our sample. Noticeably, about 50% of women aged 75 years and older report difficulty with at least one ADL, compared to only 24% of men. This disparity begins to widen among the sample at age 65, a group that includes many widows who are often left with little familial support (Sengupta and Agree, 2003). Moreover, Table 3-8 shows that this widening disparity in self-reported difficulty with ADLs does not just occur at the aggregate across all measures, but for each of the six activities asked about in LASI.

Delving deeper, we examine the socioeconomic correlates of (1) self-reported health, (2) ADL disability, and (3) a cognitive function exam administered as part of LASI (see Table 9 at http://www.hsph.harvard.

TABLE 3-7 Distribution of Difficulty with ADLs by Gender Among Respondents Aged 45 Years and Older

| Count of Difficult ADLs | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Number of Respondents | 1,236 | 95 | 42 | 19 | 12 | 14 |

| Men (%) | 88.8 | 5.8 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Women (%) | 84.2 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

NOTES: Among respondents with only one difficult ADL, the most common was getting in and out of bed; among respondents with two difficult ADLs, the most frequent were getting in and out bed and using a toilet; among respondents with three difficult ADLs, the most commonly reported were difficulty walking across a room, bathing, and using a toilet; among respondents who reported difficulty with four ADLs, the most frequent were walking across a room, bathing, using the toilet, and getting in and out of bed; and among those respondents with five difficult ADLs, the most common were walking across a room, bathing, getting in and out of bed, and the same number of respondents reported difficulty with the remaining ADLs. The sample for this table is restricted to respondents who self-reported an age of at least 45 years in the individual interview. Percentages are weighted using the pooled-state weight.

SOURCE: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

TABLE 3-8 Distribution of Difficulty with ADLs by Gender and Age

| Age | |||||||||||

| Difficulty with... | Gender | 45+ | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | 75+ | |||||

| Any ADL | Men | 11.2 | 6.7 | 10.4 | 16.6 | 24.1 | |||||

| Women | 15.9 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 22.9 | 48.4 | ||||||

| Dressing | Men | 4.7 | 2.0 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 15.5 | |||||

| Women | 4.3 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 24.6 | ||||||

| Walking across a room | Men | 4.9 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 17.5 | |||||

| Women | 7.8 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 11.8 | 29.0 | ||||||

| Bathing | Men | 3.2 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 9.4 | |||||

| Women | 5.8 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 7.4 | 26.3 | ||||||

| Eating | Men | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 5.1 | 4.3 | |||||

| Women | 6.5 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 6.5 | 29.8 | ||||||

| Getting in and out of bed | Men | 4.9 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 8.7 | 10.7 | |||||

| Women | .9 8. | 5.5 | 5.1 | 12.8 | 28.8 | ||||||

| Toileting | Men | 3.9 | 1.2 | 4.1 | 6.6 | 10.1 | |||||

| Women | 6.8 | 4.3 | 1.5 | 9.7 | 28.3 | ||||||

NOTES: Respondents were asked if “due to health or memory problem” they have difficulty dressing themselves, walking across a room, bathing, eating foods, getting in and out of bed, and using the toilet. Responses are: yes, no, can’t do, and don’t want to do. Respondents who answered yes or that they cannot do the task were considered to have an ADL difficulty. Percentages are weighted using the pooled-state weight among the sample of respondents that self-reported an age of at least 45 years.

SOURCE: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

edu/pgda/WorkingPapers/2011/PGDA_WP_82.pdf). We observe statistically significant differences in self-reported health by age group. Older respondents report poorer self-rated health as do widows, respondents from Kerala, and the less educated. The results for difficulty with ADLs are reasonably similar, with the additional indication that women (but not widows or more educated respondents) are more likely to report difficulty with at least one ADL. Unlike self-reported health, we do not observe a statistically significant effect for education after controlling for other factors.

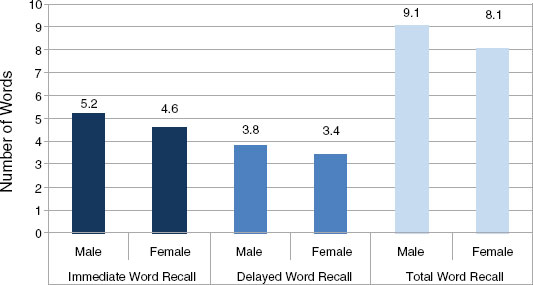

Cognitive health is a growing concern among aging populations in developing countries, yet remains understudied in India11 (Jotheeswaran, Williams, and Prince, 2010; Prince, 1997). LASI includes measures of verbal and numerical fluency, as well as episodic memory recall that have been used among low-literacy aging populations in India (Ganguli et al., 1996; Mathuranath et al., 2009). Figure 3-2 focuses on episodic word recall. LASI combines two measures of word recall—immediate and delayed—to create a summary measure used in our analysis.

Unlike in studies in the United States and the United Kingdom, women in India perform worse than men on measures of cognitive health (Lang et al., 2008; Langa et al., 2008), as shown in Figure 3-2. While women tend to be less educated and older than men in India, LASI data show the female disadvantage in cognitive health persists even after controlling for these risk factors. Similar cognitive disparity between men and women has been found in other developing countries (Zunzunegui et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the factors that account for the cognitive shortfall among women deserve further exploration (Lee et al., 2012).

Regional differences were seen in the health measures, which cover both self-reported general health and self-reported disability, and one objective measure of health: episodic memory. Respondents from Kerala report worse health, somewhat surprising given Kerala’s health system, access to community insurance, low infant mortality, long life expectancy, and high levels of education. Reasons why older people from Kerala report worse health may include the following: (1) higher morbidity and disability rates; (2) higher likelihood that people with better education and awareness report their ill health; (3) prevalence of smoking and drinking; (4) an elderly population that is older than in other states; and (5) high burdens of noncommunicable and cardiovascular diseases, including, of course, among Kerala’s older population (Kumar, 1993; Rajan and James,

____________

11 Current studies of cognitive and mental health in India are based on small sample sizes from single cities, ignoring sociocultural and regional variation. Moreover, many of these studies examine dementia and specific neuro-degenerative diseases, while ignoring possibly more prevalent and sub-clinical forms of cognitive health impairment.

FIGURE 3-2 Cognitive performance among respondents 45 years and older by gender.

NOTES: The immediate word recall task asks respondents to recall as many words as they can from a list of 10 words immediately after the interviewer reads them aloud. Delayed word recall asks respondents to name as many words as they can after completion of a cognitive functioning questionnaire. Both delayed and immediate word recall are scored with a maximum of 10 words. Total word recall is the sum of these two. Three lists of 10 words were used, and were randomly assigned to a respondent. The standard deviation for immediate word recall pooled across both men and women was 1.9, 2.0 for delayed recall, and 3.5 for total word recall. Data for the graph are limited to respondents who self-reported an age of at least 45 years. Statistics reported in the figure are weighted by the pooled-state weight.

SOURCE: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

1993; Suryanarayana, 2008). There are also large differences between Kerala and the other states with regard to cognitive health.

As another example of health issues faced by older Indians, Table 3-6 reports the results of self-reported food insecurity among respondents. These levels may seem low for India, but they reflect substantial efforts on the part of the Indian government to reduce hunger and famine. Examining another measure, such as body mass index, illustrates that basic food provision is still a concern (see “Underweight” in Table 3-6). Body mass index has proven to be an effective marker for chronic energy deficiency in developing countries (Chaudhuri, 2009; Ferro-Luzzi et al., 2009; Nube et al., 1998). Rajasthan has the highest prevalence of underweight individuals, yet lower rates of self-reported hunger and food shortage. Com-

TABLE 3-9 Who Pays for Healthcare?

| Respondent Characteristics | Relies on Family to Pay |

| Aged 55-64 | 0.112 |

| (1.05) | |

| Aged 65-74 | 0.242* |

| (2.12) | |

| Aged 75+ | 0.463** |

| (2.85) | |

| Female | 0.437*** |

| (3.94) | |

| Education (yrs) | −0.033* |

| (−2.44) | |

| Rajasthan | −1.069*** |

| (−4.10) | |

| Kerala | −0.261 |

| (−1.52) | |

| Karnataka | −0.824*** |

| (−5.28) | |

| Rural | −0.060 |

| (−0.52) | |

| Scheduled caste | −0.299 |

| (−1.83) | |

| Scheduled tribe | −0.211 |

| (−0.70) | |

| Other backward caste | −0.252* |

| (−2.31) | |

| HH Consumption (middle tertile) | −0.225 |

| (−1.74) | |

| HH Consumption (highest tertile) | −0.304* |

| (−2.08) | |

| Episodic memory 1 | −0.662* |

| (−2.23) | |

| Episodic memory 2 | −0.807* |

| (−2.59) | |

| Episodic memory 3 | −0.451 |

| (−1.73) | |

| Any ADL disability | −0.028 |

| (−0.21) | |

| Chronic condition | −0.023 |

| (−0.24) | |

| Working | −0.069 |

| (−0.48) | |

| Constant | 1.399*** |

| (3.72) | |

| N | 1,311 |

| F-stat | 6.45*** |

| Estimator | probit |

NOTES: In this model, we create a categorical scheme for our measure of cognitive health using episodic memory recall. We derive four dummies: episodic memory 1 includes respondents (18%) who were able to recall 0 to 5 words out of 20; episodic memory 2 includes respondents with 6 to 10 words (54%); episodic memory 3 includes respondents with 11 to 15 words, and the final category (omitted) was for the 3% of respondents who could recall 16 or more of the 20 possible words. The sample is restricted to respondents who self-reported an age of at least 45. Chronic condition is self-reported diabetes, heart disease, lung disease, stroke or hypertension. Working is defined as engaging in any labor market activity in the past 12 months; and any ADL is a binary indicator for having difficulty with at least one ADL. LASI used a stratified sampling design that sampled respondents independently by state, rural-urban area, and district. All multivariate models are unweighted, and the standard errors have been corrected for design effects of stratification. Table presents coefficients with t statistics in parentheses. * denotes p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

SOURCE: Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

paring these results to self-reported measures highlights the multiplicity of health concerns among the aging Indian population, and the difficulty in ascertaining accurate reports of disease burden.

Table 3-9 indicates that many aging Indians rely on their family networks to pay for healthcare. Although India has free, government-sponsored public healthcare, most Indians, even the poorest, opt to use private services over government facilities (Gupta and Dasgupta, 2003). However, with longer lives, an increasing chronic disease burden, rising healthcare costs, and a shortage of service facilities and healthcare workers in India, the older population’s access to healthcare is increasingly tenuous. In the LASI data, more than 80% of respondents indicated that they themselves or their family would have to pay for any sort of healthcare. We focus on this set of respondents below, fitting a multivariate model to better understand the determinants of family-reliance for healthcare costs.12

The results reflect notable demographic and regional differences in healthcare accessibility. Older members are increasingly reliant on their family for support, as are women, perhaps because of more complex medical needs and little cash-earning potential. By contrast, respondents with more education and higher household socioeconomic status are more likely to pay out of their own pocket, suggesting that households responsible for the well-being of their aging family members are among the poorest.

____________

12 Respondents are considered to “rely on family to pay” if they wholly (48.2%) or partially (12.9%) rely on the family to finance the costs, either out of pocket or through a family member’s insurance scheme (6.0%). Respondents not considered to rely on family indicated that they alone finance their healthcare out of pocket (38.9%).

In addition, these results13 reflect the traditional intra-household support system, but they also suggest important levers for implementing policy to ensure well-being in old age. Women tend to be more reliant on family networks for access to healthcare. Older respondents also tend to rely on family members, which reflects loss of economic agency and increasing burden of age-related morbidities. Finally, there is some interesting regional variations. Respondents in Rajasthan and Kerala are much less likely to have family members who would pay for their healthcare, despite the larger household sizes. The same pattern holds in comparatively more developed Karnataka. Another salient finding is that individuals who report working in the past year are more likely to rely on themselves for healthcare. (This model excludes respondents who reported having their healthcare expenses paid by their employer or by an insurance company.) Further analysis of who provides and who pays for elder care, as well as who makes the decisions and what drives those decisions, is possible using the LASI pilot data and would be worthwhile.

Regional associations should, of course, be interpreted with caution. While respondents from both Karnataka and Rajasthan are more likely to rely on their own out-of-pocket expenditures for healthcare, the two states have vastly different socioeconomic profiles. While Karnataka is more affluent, as noted earlier, Rajasthan is one of the poorest states in India, with the aging men and women largely paying for their own medical expenses out of pocket.

Measuring Health: Innovations in LASI

State-of-the-art survey methods,14 in addition to their diverse measures to assess the multiplicity of health concerns, are a hallmark of LASI. For example, anchoring vignettes permit refined analysis of many subjective survey responses. The World Health Organization has made

____________

13 We also present results from additional models of healthcare utilization in an earlier and more detailed version of this paper, which is available online at http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/pgda/WorkingPapers/2011/PGDA_WP_82.pdf. The models further corroborate our understanding of patterns of healthcare use among the aged in India, drawing support from a wider range of outcome variables to model visiting a doctor when ill, undiagnosed hypertension, and preventive measures such as a cholesterol check. These models reflect demographic, regional, and economic patterns that we observe in this paper.

14 LASI also includes innovations that are not related to health. Among them are (1) some specific types of questions about assets and income; (2) use of a geographic information system database to support community-level analysis; (3) questions about water quality, sanitation, and safety in the neighborhood; and (4) questions about a broad range of psychological, social, and behavioral risk factors (e.g., measuring social connectedness in addition to traditional social network questions).

extensive use of vignettes in several of its SAGE surveys around the world (Kowal et al., 2010), as have several of LASI’s sister surveys.

Anchoring vignettes allow researchers to correct for cross-person heterogeneity in the subjective nature of responses to some health questions by asking respondents to characterize a set of short hypothetical stories (vignettes) that describe fictional individuals with varying health problems. Respondents’ scoring of a common set of vignettes may allow researchers to standardize answers to self-health questions that naturally require subjective answers.15

However, vignettes can only serve their intended purpose if respondents can understand and make reasonable assessments of them. For example, respondents should rank a vignette intended to describe someone in extreme pain as exhibiting a much higher level of pain than one intended to show very mild pain. If a respondent does not rank the vignettes in the intended order, the scoring should not be used to adjust the respondent’s answers to questions about severity of pain.

In the LASI pilot, roughly one-half the respondents ranked the vignettes in an order that was different from the intended order. In these cases, it was therefore impossible to use the vignettes to adjust respondents’ answers. Several studies explore the reasons for unexpected results in vignette ranking and possible means for avoiding or remedying such situations (for example, Delevande, Gine, and McKenzie, 2010; Gol-Propoczyk, 2010; Hopkins and King, 2010; Lancasr and Louviere, 2006; and Mangham, Hanson, and McPake, 2009). Because this required us to ignore a large fraction of respondents, we caution against extrapolating these results to a larger population. We did a multivariate analysis to try to find patterns that distinguish those whose answers we had to ignore from those that were usable, but no significant patterns emerged.

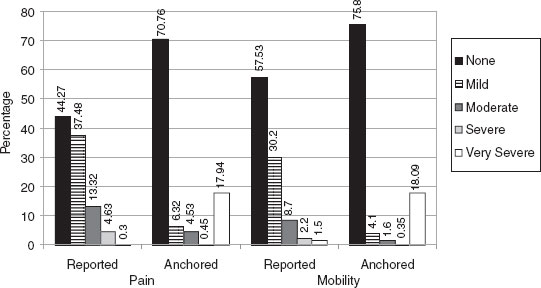

Using data restricted to respondents whose vignette rankings were in the expected order, Figure 3-3 shows the results of two anchoring vignettes for pain and mobility. Respondents were asked to rate the degree to which they experience bodily aches and pains and have trouble moving around. The vignettes suggest respondents who have some difficulty moving around and report some chronic pain tend to underreport the severity.16

____________

15 The vignettes module in LASI is randomly assigned to one-third of the sample (n = 463); it is one of three experimental modules in the survey. In addition to vignettes about pain and difficulty with mobility, other vignettes include sleep difficulty, concentration, shortness of breath, feeling sad/low/depressed, bathing, and personal relationships.

16 Here, we are careful to distinguish between measures of disability and the questions in the vignette section, which may at first seem incongruent. The six questions about ADL ask specifically if the respondent is unable (without help) to do a series of tasks because of a “health or memory problem.” However, the vignettes ask much more generally about pain and mobility: an older person, for example, may have chronic back pain, but otherwise be

FIGURE 3-3 Pain and mobility difficulty vignettes for LASI respondents aged 45 years and older.

NOTES: The sample size is 232 for pain and 202 for mobility, among respondents who self-reported an age of at least 45 years. Responses are weighted using the pooled state-weight.

SOURCE: Data from Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) Pilot Wave.

The data imply nearly one-fifth of respondents could have very severe pain or mobility problems, while less than 2% for each domain reported so originally. For both pain and mobility, the number of respondents who experience “none” is much higher than initially reported, while the number of respondents who have very severe problems within either domain increases substantially.

Social and Civic Participation among the Aged and Aging

Aside from physical and economic well-being, LASI provides a snapshot of daily life, particularly social and civic participation in local communities. The LASI pilot found that men tended to be more social than women and that the most common social activities17 for both sexes were visiting friends/relatives, attending cultural events or performances, and

able to move around by him or herself, use the toilet, eat a meal, bathe, and get dressed. Among older populations, this sort of pain is likely to be more prevalent than severe disabilities that prevent someone from functioning day to day.

17 For social activities, LASI asks about going to the cinema, eating outside the house, going to a park or beach, playing cards or games, visiting relatives/friends, attending cultural performances/shows, and attending religious functions/events.

attending religious festivals and functions. Men were more likely than women to report eating outside the home, visiting a park or beach, and playing cards or games. Sex differences in social participation are present even when stratified by age. Overall, social participation declines for both men and women in the LASI sample as respondents age. For example, prevalence of visiting friends or relatives drops from 85% among women aged 45 to 54 to 58% among women aged 75 and older.

In the LASI sample, civic participation18 is much less common overall than social activity, but is more common among women than men (although gender differences drop out in the multivariate models below). This is likely because LASI asks about mahila mandal, a women’s self-help and empowerment group. Evidence is limited that women participate in caste and community organizations, as well other activities. Men participate in self-help and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)/senior citizen clubs/farmers associations, and community and caste organizations.

In results not reported here (but included in the earlier online version of this paper), we explored the association between the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, and civic and social participation. Because civic participation was relatively low in the LASI sample, we estimate a probit model and regress a binary indicator for any civic participation on the list of covariates. Social activities are more common than civic participation. We look at social participation by regressing the number of social activities per month on the same list of covariates using OLS estimation. We see a significant negative association with age and civic participation only among respondents at least 75 years of age. Respondents with more years of education were also more likely to participate in their community, as were respondents in the two southern states. An association between civic participation and health, as measured by difficulty with at least one ADL, is not apparent.

Social participation shows a similar association with age, with a statistically significant decrease in social participation in age only among respondents aged 75 and older. After controlling for the full set of respondent characteristics and regional indicators, we no longer see a sex difference in civic participation. We do see a statistically significant decrease in social participation among women, but this is not attributable to lower educational attainment or older age. Respondents in Rajasthan and Kerala

____________

18 LASI asks about respondents’ participation in farmers’ associations/environmental groups/political parties/senior citizen clubs; tenant groups, neighborhood watch, community/caste organizations; self-help group/NGO/cooperative/mahila mandal; education, arts or music groups, evening classes; social clubs, sport clubs, exercise classes, and any other organizations that we consider civic participation.

were less likely to participate in social activities compared with those in other states.

These models provide some evidence that aging Indians continue to stay involved in their communities as they age. They stop working for pay, are active outside the home, and participate in broader civic and social networks. The LASI pilot suggests research in civic and social networks in India is promising. Previous studies have supported the importance of civic and social participation for successful aging and health, and we see some evidence of that with the connection between difficulty with activities of daily life and social participation (Berkman et al., 2000; Moen, Dempster-McClain, and Williams, 1992; Seeman and Crimmins, 2006).

Economic Well-Being of the Aging

LASI provides considerable information about the economic activity and well-being of India’s aging population. Workforce participation, for example, is central in a country without social security or pensions, particularly as intergenerational support—once the traditional and widespread means of old age support—becomes less common (Bloom et al., 2010). Given that less than 11% of older people in India have access to a pension or social security, economic activity is especially important. Additionally, private saving is often difficult or entirely infeasible for several reasons: earnings are low, a significant portion of the economic activity is informal and may not be tied to cash exchange, and bank accounts are often not available in rural India (Uppal and Sarma, 2007).

We examine labor force participation (defined as any employment, self-employment, or agricultural work in the past 12 months) in the LASI sample among respondents who are aged 45 and older. Table 3-10 presents five models of labor force participation. The results show older respondents are less likely to work, particularly in urban areas. Women are less likely to report having worked, as are respondents who report difficulty or disability with at least one ADL. The association between disability and economic activity points to the important relationship between health and economic well-being among the vulnerable and aging Indian population, although one cannot infer the direction of causality. These findings are consistent with results of similar studies (Bakshi and Pathak, 2010). Studies from other developing countries, such as China, have found health is a significant correlate of labor market participation among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations (Benjamin, Brandt, and Fan, 2003).

We do not see employment differences by education or caste. Respondents in Rajasthan are more likely to be working than respondents in other states. This finding is consistent with the largely agricultural economies in

Rajasthan and other rural areas, which absorb older workers more consistently in comparison with manufacturing and other types of economies in developing countries (Bakshi and Pathak, 2010; Nasir and Ali, 2000).

Education is not correlated with labor force participation among our sample aged 45 years and older, with the exception of the model for nonagricultural labor. Consistent with the literature, respondents with more education are slightly more likely to engage in nonagricultural labor than those with less, even after controlling for a variety of socioeconomic and regional indicators. However, our findings are somewhat inconsistent with results elsewhere that suggest educated individuals are more likely to accumulate savings and participate in formal labor markets, leading to earlier labor-market withdrawal. Our estimates reveal insignificant associations with education and all other forms of work across rural and urban sectors. However, the model could mask regional heterogeneity: When we estimate the models without state dummies, we find statistically significant relationships between education and labor force participation in nonagricultural sectors, work in rural areas (model 2), and agricultural work (model 4). In these three models without state dummies, more educated individuals were less likely to be working. Regional differences in availability of pension schemes, old age support, and labor markets account for the association between education and labor force participation in our sample. Given the lack of social security, pension, and health insurance available to most Indians, continued workforce participation is vital. However, working imposes a strain on aging individuals, and many often do so out of desperation or necessity. Policies can focus on the health of the aging workforce, so they may stay engaged in more productive work.

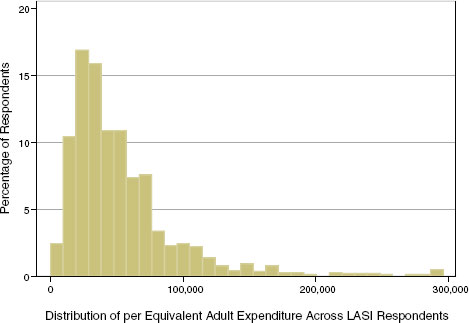

We also examine household expenditure. Among households, we analyze the demographic and regional correlates of household consumption expenditure to understand socioeconomic gradients in the LASI sample and to some extent in India as well. Figure 3-4 displays the distribution of annual household expenditure (in rupees, and including imputed amounts) per equivalent adult across LASI respondents aged 45 and older. Equivalency scales developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are used to account for economies of scale in household consumption.19

Table 3-11 reports three regression models of household expenditure per equivalent adult among LASI respondents. Large households tend to have lower per capita expenditure. Across the pooled urban and rural sam-

____________

19 Equivalent adults are calculated counting the first person aged 18 and older as 1.0 equivalent adults, each additional person aged 18 and older as 0.7 equivalent adults, and each person under age 18 as 0.5 equivalent adults. See http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/61/52/35411111.pdf

TABLE 3-10 Demographic and Regional Variation in Binary Indicator for Any Employment in Past Year

| All Work, Rural and Urban Respondents | All Work, Rural Respondents | All Work, Urban Respondents | Agricultural Work, Rural Respondents | Nonagricultural Work, Urban, and Rural Respondents | |

| Aged 55-64 | -0.417*** | -0.374** | -0.522* | -0.200 | -0.357** |

| (-4.23) | (-3.42) | (-2.33) | (-1.94) | (-3.29) | |

| Aged 65-74 | -0.689*** | -0.612*** | -0.966** | -0.317* | -0.542** |

| (-5.69) | (-4.33) | (-4.31) | (-2.39) | (-3.37) | |