Quality of Life and Community Resources

Having epilepsy is about much more than having seizures. People with epilepsy and their families typically face an array of challenges to daily living that vary with the severity and nature of the epilepsy disorder and that may change as the individual gets older. The negative effects on quality of life can be severe and involve family and social relationships, academic achievement, and opportunities for employment, housing, and the ability to function independently. Family and community support is critical across a range of services. Improvements in community services and programs are needed to ensure that they are individually centered to meet the needs of the person with epilepsy; locally focused, taking into account the full range of resources in the area; easily accessible; thoroughly evaluated; closely linked to health care providers, particularly epileptologists and epilepsy centers; and innovative and collaborative. Actions necessary to achieve these goals include identifying and disseminating best practices in the provision of epilepsy services and innovative collaborations with organizations and agencies focused on other neurological and chronic conditions or on similar service needs.

We saw four pediatric neurologists in that first year. The fourth doctor told us to stop worrying about stopping the seizures because he could not figure out her EEG [electroencephalogram]. He told us to concentrate on her quality of life. She was 4, not talking, no longer walking, and could not even smile. We were losing everything. What quality of life did she have and where was the bottom of this spiral? We did not want to find out, but we did. We now live at the bottom of the spiral looking up.

-Janna Moore and Tom Weizoerick

It is a terrifying helplessness that one feels as a parent knowing that your child’s brain is misfiring so badly that if left to continue untreated it will result in a vastly reduced life expectancy and severely reduced intellectual function.

-Jeffrey Catania

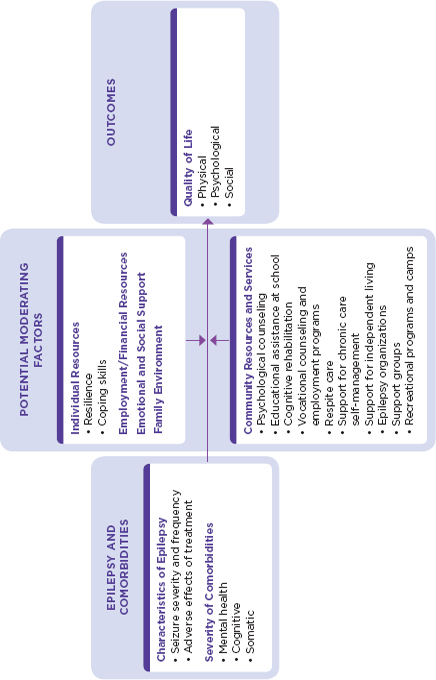

Epilepsy is much more than seizures. For people with epilepsy, the disorder is often defined in more everyday terms, such as challenges in school, uncertainties about social and employment situations, limitations on driving a car, and questions about independent living. Family members also may struggle with how to best help their loved one and maintain their family life. Because of the range of seizure types and severities and the high rate of comorbid health conditions, the types of issues that have an impact on quality of life for people with epilepsy and their families and the degree to which they are affected vary widely. As a result, the range of community services potentially needed may be extensive (Table 6-1).

This chapter aims to provide a brief introduction to the diversity of ways in which the lives of people with epilepsy are affected by the disorder and the range of community efforts that can provide support and assistance. The chapter begins with an overview of quality of life and the facets of quality of life that are particularly relevant for differing age groups. The major areas of focus for community services are then discussed—families, day care and school, sports and recreation, employment, transportation, housing, and first aid training—with each section providing the committee’s thoughts on next steps and opportunities to be explored. The chapter concludes with a discussion of navigating the broad array of community services and cross-cutting opportunities to improve services for people with epilepsy and their families.

OVERVIEW OF THE IMPACTS OF EPILEPSY ON QUALITY OF LIFE

Quality of life is a person’s subjective sense of well-being that stems from satisfaction with one’s roles, activities, goals, and opportunities, relative to that individual’s values and expectations, within the context of culture, community, and society. According to the World Health Organization (1996), “Quality of life is defined as individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (p. 5).

The term “health-related quality of life” is generally used when referring to quality of life in the context of a person’s health status (CDC, 2011a; Wilson and Cleary, 1995). Health-related quality of life is multidimensional, and for people with chronic conditions such as epilepsy, it is often related to functioning in three areas: physical, psychological, and social (Elliott and Mares, 2012; Koot, 2001; Solans et al., 2008). For the

TABLE 6-1

Spectrum of Potential Epilepsy-Related Needs and Community Services

| Types of Needs | Community Services |

| Information needs about the disorder, treatments, and health services (Chapter 7) |

• Nonprofit organization websites with general information about epilepsy (e.g., epilepsyfoundation.org; epilepsy.com) • Nonprofit organization websites with information specific to an epilepsy syndrome (e.g., dravet.org; tsalliance.org) • Federal and state websites and information resources • Health care providers, including community health workers • Case managers and social workers |

| Information needs about local community services |

• State and local Epilepsy Foundation affiliatesa • Nonprofit organizations • Social workers, case managers |

| Help in coping with the disorder and the associated comorbidities and challenges |

• Support groups • Self-management programs • Counseling |

| School-related needs |

• Cognitive testing and educational assistance • Individualized education programs (IEPs) • Teachers and school counselors who are informed about epilepsy |

| Employment-related needs |

• Vocational programs, vocational rehabilitation programs • Disability-related organizations and government agencies |

| Transportation-related needs |

• Social service organizations • Local transportation agencies • Government agencies |

| Housing-related needs |

• Social service organizations • Nonprofit organizations, including faith-based organizations • Government agencies |

| Recreation and leisure |

• Camps • Sports and recreational programs |

| Assistance for family members and caregivers |

• Respite care programs • Support groups for family members |

NOTE: As indicated throughout the report, family members, friends, caregivers, and others are key providers of social and psychosocial support.

a The Epilepsy Foundation is a nonprofit organization with a national office and more than 50 affiliates nationwide that offer varying services.

SOURCE: Adapted from IOM, 2008.

purposes of this report, the committee uses the term quality of life to incorporate health-related quality of life. Many of the physiological aspects of improving quality of life (e.g., improved treatment options, optimal care, improved access to care) are discussed in Chapter 4.

The burden of seizures and epilepsy, particularly severe forms of epilepsy or disabling comorbidities, can be overwhelming for many individuals and their families. The social and emotional toll of care (sometimes round-the-clock care) can place financial and emotional strains on marriages and families, altering roles, relationships, and lifestyles. Family members may need to take extensive leave or unexpected days off work that can disrupt careers and drain family finances. Many speakers at the committee’s workshops emphasized that epilepsy—regardless of its level of severity—creates life challenges because of the unpredictability of seizures (Box 6-1).

Studies that have examined the economic impact of epilepsy find that the indirect costs to society (productivity-related costs) generally exceed direct costs (treatment-related costs). A number of validated generic and epilepsy-specific instruments are used to assess quality of life (Chapter 2). In a systematic review of 22 cost-of-illness studies conducted around the world, among those that used reasonably comprehensive accounting for indirect cost, the indirect costs of epilepsy ranged from 12 to 85 percent of total costs (Strzelczyk et al., 2008). A study of the cost burden of epilepsy in the United States estimated a total annual cost of $12.5 billion per year, $10.8 billion in indirect costs (86.5 percent) and $1.7 billion in direct costs (13.5 percent) (Begley et al., 2000). Overall, lifetime productivity is estimated to decline 34 percent for men and 25 percent for women. Estimates of indirect costs are significantly higher for people with refractory epilepsy (Begley et al., 2000).

Children and Adolescents

In general, research comparing quality of life across different chronic conditions indicates that children and adolescents with epilepsy have a relatively high physical quality of life, but fare much worse in the psychological and social quality-of-life domains. For example, in a study comparing children with epilepsy with children with asthma, those with epilepsy had better quality of life in the physical domain but significantly lower quality of life in the psychological and social domains (Austin et al., 1994).

Many studies have focused on the psychosocial challenges faced in childhood. Recent comparison studies demonstrate that children and adolescents with epilepsy have relatively more social problems than children and youth who do not. Social problems in children and adolescents include feelings of being different, social isolation, and being subject to teasing and bullying (Elliott et al., 2005). Children with epilepsy who were 3 to 6 years

At the March workshop, Lori Towles, the mother of Max, who is 17 years old, detailed the impact of epilepsy on Max and their family. Max had brain surgery in 2010 to remove the lesion that was causing his seizures and in December 2011 celebrated 18 months of being seizure free.

$3,000 The amount I’ve paid to an advocate to secure services for Max at his current high school because of the ignorance of the school district regarding epilepsy and students with medical disabilities

19 Anti-seizure pills Max has taken per day

10 Medical and service providers that make up Max’s support team

9 Anti-seizure medications he’s tried

6:30 Pill-time—morning and night—it’s set as an alarm on everyone’s cell phone in the house

5 Number of caring and gifted teachers that have come to the house to teach math, English, and science in the last 3 years

4 Number of neurologists he sees regularly

3 Number of times Max has received the Anointing of the Sick

2 Number of additional diagnoses: ADD at age 7 and anxiety at age 10 due to the seizures

1 Years of home schooling while we tried to find a working combination of medications to control the seizures

0 Number of times he has said, "Why me”

0 Number of friends he has now

Countless

• Hours waiting in line at the pharmacy, driving to doctors’ appointments, and documenting his seizure activity

• Days missed from school due to seizures

Insulting and rude remarks made by classmates (ignorant and informed) because of his twitching, mumbling, seizing, and falling asleep in class

• Meetings, e-mails, and phone calls to his teachers and school support personnel to explain what to expect with his medical condition

• Days missed from my work to take him to doctors appointments, have meetings at school, and just be there for him

• Minutes where my daughter and I watch Max slip away into another place while his brain seizes

• Prayers from family and friends, coworkers, and neighbors

_____________

NOTE: ADD = attention deficit disorder.

old showed fewer age-appropriate social skills (Rantanen et al., 2009). Children with epilepsy ages 8 to 16 were found to have significantly lower social skills (cooperation, assertion, responsibility, and self-control) compared to healthy children; however, they did not differ significantly in social skills from children with chronic renal disease (Hamiwka et al., 2011). In a somewhat older group, youth ages 11 to 18 with epilepsy had poorer social competence, with girls having significantly less social competence than boys (Jakovljevic and Martinovic, 2006).

Having a chronic condition might help explain some of the poorer social skills described among children with epilepsy (Hamiwka et al., 2011). Beyond that possibility, Caplan and colleagues (2005) identified a number of other variables associated with social problems in children with epilepsy, including lower IQ, externalizing behavior problems, racial/ethnic minority status, and impaired social communication skills. In this study, seizure variables (e.g., age of onset, frequency, duration) were not related to social functioning. In addition, a prospective study of children and adolescents who had epilepsy surgery showed no changes in social functioning one year later, regardless of surgery outcome (Smith et al., 2004); however, improvement in social functioning was found after 2 years (Elliott et al., 2008). In childhood epilepsy, school performance and academic achievement are commonly affected, as described later in this chapter.

Compared to children with other chronic health conditions, siblings, and control groups, children with epilepsy are at increased risk for mental health conditions such as depression and attention problems (Rodenburg et al., 2005). In the 1999 nationwide British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey, rates of mental health comorbidities were higher in children with epilepsy (37 percent) than in children with diabetes (11 percent) or in control children (9 percent). In children with epilepsy and another type of comorbidity, such as cognitive or neurological deficits, the rate of mental health comorbidities was even higher (56 percent) (Davies et al., 2003). Children with epilepsy and intellectual disability have high rates of mental health conditions; in one study, more than 90 percent of children with epilepsy and intellectual disability could be classified as having a psychiatric diagnosis also (Steffenburg et al., 1996). A meta-analysis of 46 studies found that internalizing problems such as anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal were more common in children with epilepsy than externalizing problems such as aggression or delinquency (Rodenburg et al., 2005).

Prior to the past decade, it was generally assumed that mental health conditions and other comorbidities occurred in response to having a chronic condition, such as epilepsy. Studies of children with new-onset seizures, however, have demonstrated that mental health conditions, cognitive problems, and behavioral problems can occur very early in the disorder and in some cases precede the onset of seizures (Austin et al., 2001, 2011;

Jones et al., 2007; Oostrom et al., 2003). In addition, epidemiologic studies have shown that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other mental health conditions are risk factors for developing seizures in children (Hesdorffer et al., 2004; McAfee et al., 2007) (Chapter 3).

A number of other risk factors for mental health comorbidities have been identified. Seizure severity and frequency are associated with an increase in mental health comorbidities in some but not most studies (Austin and Caplan, 2007). Family-related psychosocial variables, such as greater family stress, fewer family resources, negative child and parent attitudes about epilepsy, poorer coping skills, and poorer family adjustment also were associated with higher rates of mental health comorbidities in children (Austin and Caplan, 2007). The authors concluded that research has not identified the causal direction of children’s mental health comorbidities and that disruptions in the family environment and mental health conditions in the child are most likely reciprocal.

Although for some individuals, epilepsy is an experience of childhood with seizures stopping during adolescence or early adulthood, for many other people seizures continue into adulthood and others live with the long-term effects that seizures have had on their cognitive or social development (Geerts et al., 2011; Kokkonen et al., 1997; Shackleton et al., 2003). For example, a 35-year prospective, population-based study in Finland found that compared to adults without epilepsy, adults who had epilepsy during childhood had poorer social outcomes in adulthood; they had less formal education, were less likely to be married or have children, and were more likely to be unemployed (Jalava et al., 1997; Sillanpää et al., 1998). Adverse lifespan outcomes have been found to be associated with histories of neurobehavioral comorbidities including early learning or cognitive and psychiatric problems (Kokkonen et al., 1997; Shackleton et al., 2003). In working to reduce the health and quality-of-life impacts of epilepsy, it is critical to address the needs of all individuals affected by the disorder.

Adults

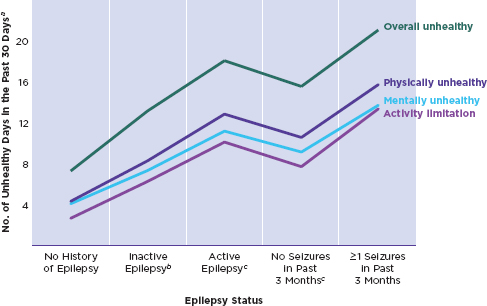

Surveys of adults have identified risk factors for reduced quality of life for people with epilepsy, including having a greater number of seizures, longer duration of seizures, and earlier age of seizure onset (Baker et al., 1997; Jacoby and Baker, 2008; Kerr et al., 2011; Wheless, 2006). Other factors affecting quality of life include side effects of seizure medications, lack of adherence to medications, depression or anxiety, lack of social support, stigma, and concerns about employment (Aydemir et al., 2011; Baker et al., 2005; Hovinga et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2011b). Higher rates of comorbid mental health conditions for adults with epilepsy compared to those without are described in Chapter 3, and large surveys indicate that adults

with epilepsy are relatively likely to report more mentally and physically unhealthy days per month than adults without epilepsy, with the highest rates found in those with seizures in the past 3 months (Kobau et al., 2007, 2008; Wiebe et al., 1999) (Figure 6-1).

Results from a large U.S. survey also indicated poorer social outcomes for adults with a history of epilepsy, compared to those without, including being less likely to be married and more likely to have lower levels of education, employment, and income (see Table 6-2 and discussion later in this chapter on employment and epilepsy) (Kobau et al., 2008).

Older Adults

The quality of life for older adults with epilepsy is understudied (Devinsky, 2005). A recent study by Laccheo and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that older adults with epilepsy have a significantly lower quality of life across all domains when compared with the general population.

FIGURE 6-1

Health-related quality of life in adults with epilepsy.

aSelf-reported measure of health-related quality of life (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data).

bRespondents with self-reported, doctor-diagnosed seizure disorder or epilepsy who had not had a seizure in the past 3 months and were not taking medication to control epilepsy.

cRespondents with self-reported, doctor-diagnosed seizure disorder or epilepsy who were currently taking medication to control it, had one or more seizures in the past 3 months, or both.

SOURCE: CDC, 2011b; based on data from Kobau et al., 2008.

TABLE 6-2

Comparison of Adults With and Without a History of Epilepsy

| With History of Epilepsy (n = 2,207)% | Without History of Epilepsy (n = 118,638)% | |

| Marital status | ||

|

• Married or unmarried couple |

55.5 | 64.1 |

|

• Formerly married |

22.9 | 18.0 |

|

• Never married |

21.5 | 17.9 |

| Income | ||

|

• < $25,000 |

40.9 | 26.3 |

|

• $25,000 to $49,999 |

30.0 | 29.7 |

|

• ≥$50,000 |

29.2 | 43.9 |

| Employment status | ||

|

• Employed |

45.8 | 61.6 |

|

• Unemployed |

6.8 | 5.0 |

|

• Unable to work |

23.7 | 4.8 |

|

• Other (homemaker, student, or retired) |

23.7 | 28.6 |

| Could not visit doctor because of cost | ||

|

• Yes |

23.7 | 13.4 |

|

• No |

76.3 | 86.6 |

| Self-rated health | ||

|

• Good, very good, or excellent |

63.0 | 84.2 |

|

• Fair or poor |

37.0 | 15.8 |

| Life satisfaction | ||

|

• Very satisfied or satisfied |

83.4 | 94.6 |

|

• Dissatisfied or very dissatisfied |

16.6 | 5.4 |

SOURCE: Kobau et al., 2008.

Because a relatively higher percentage of epilepsy in older adults is a result of stroke, brain tumor, or dementia (Chapter 3), each with the potential to decrease quality of life, it might be anticipated that compared to other people with epilepsy, the quality of life would be lower in older populations. However, this study did not find a difference in quality-of-life scores between older adults with epilepsy and other age groups with epilepsy (Laccheo et al., 2008). The authors noted that instruments evaluating all facets of quality of life for older people with epilepsy need to be developed (Laccheo et al., 2008).

The impact of epilepsy on quality of life may reflect some differences by age and time since diagnosis. A study of three adult groups (young, middle-aged, and older) with epilepsy found that young and middle-aged adults had higher physical functioning and poorer psychological functioning than

older adults (Pugh et al., 2005). The authors propose that having epilepsy made it more difficult for middle-aged adults to accomplish the many tasks of middle age, such as providing financial and emotional support to the family, mentoring the younger generation, and providing support to aging parents. In other studies, quality of life was not found to differ between older and younger people with epilepsy, however, older adults diagnosed later in life reported more anxiety and symptoms of depression than those diagnosed earlier (Baker et al., 2001) and more concern about medication side effects (Martin et al., 2005).

My family and I took a trip to Florida once, and in the midst of my enjoyment and bliss, [my brother], who had been seizure-free for a couple months, had a relapse. [It] sent my parents into shock, my sister into tears, and me into a hurricane of resentment, fear, anger, and hatred. Why did he have to have these things at the most inopportune times? … I was afraid [my brother] would die, but I disliked that every family conversation focused on his disease. And I didn’t want to disturb the already fragile nest which was my family by inserting my own issues regarding the situation.

-Joseph Abrahams

[W]hen I was 12 years old, my mother, who had suffered a stroke at the age of 29, had begun to have seizures. ln the coming weeks she was diagnosed with epilepsy and our lives were never the same…. As an adolescent, I struggled with being my mother’s primary caretaker…. I vacillated between fear and anger, grief and bitterness, self-sacrifice and resentment. These emotions are often conveyed by parents of children with epilepsy, but l’m here to tell you that those feelings are no less intense for the children of those who suffer. lmagine being the one immediately responsible for a patient’s care—and now imagine shouldering that burden as 12- or 13-year-old.

-Carmita Vaughan

Epilepsy in one family member can negatively affect the quality of life of the entire family (Baker et al., 2008; Ellis et al., 2000; Lv et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2011a). Epilepsy can be more disruptive to the family than many other chronic conditions because of its hidden, episodic, and unpredictable nature; potential for injury and death; frequency of comorbidities; and associated stigma. Episodic chronic health conditions are considered among the most stressful for families, because even during periods of no symptoms, the family remains on alert in anticipation of problems (Rolland, 1994). Concerns about the safety and possible death of the person with epilepsy can further increase the stress and anxiety experienced by families. Comorbidities, such as depression and cognitive deficits, present additional demands on the family’s attention. Finally, the stigma associated

with epilepsy and the possible fears that people with epilepsy and their families associate with seizures in public can curtail social and leisure activities, increasing social isolation and further reducing quality of life (Ellis et al., 2000; Fisher, 2000).

The literature contains few studies focusing on the quality of life of the family, rather than the person with epilepsy, and most family studies assess effects on the parents of children with epilepsy (Ellis et al., 2000). Studies comparing families of children with epilepsy to families of children with other chronic conditions or healthy children consistently demonstrate that families of children with epilepsy experience more dysfunction and parental anxiety, depression, and worry (Lv et al., 2009; Rodenburg et al., 2005).

Although families of adults and older adults with epilepsy have been studied much less, findings indicate that the quality of life of these families is similarly affected (Ellis et al., 2000). Research is needed to identify the impact on the quality of life and psychosocial adjustment of family members and the services that might be particularly helpful to them in learning to cope. Limitations of the literature include small sample sizes, studying only one person from each family, focusing on mothers, an underrepresentation of men and racial/ethnic minorities, and a lack of focus on families with very young children (Duffy, 2011).

The committee’s vision is for all family members of people with epilepsy to have access to resources, support, and services that would allow them to make an optimal adjustment to having a family member with epilepsy and to attain the highest possible physical, emotional, and social well-being.

The next section reviews what is known about the impact of epilepsy on the quality of life of the family, followed by how these negative effects can be reduced by improving programs and services. Three broad areas are discussed: emotional health, family social and leisure activities, and employment and role expectations.

Impact on the Emotional Health of Family Members

Epilepsy can have a negative effect on the emotional and psychological health of family members. Parents of children with epilepsy—the most studied group—had high rates of worry, stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms; this is especially true for parents of children with refractory epilepsy (Duffy, 2011; Lv et al., 2009; O’Dell et al., 2007b; Taylor et al., 2011a; Thompson and Upton, 1992; Wood et al., 2008). A common parental worry focused on the future of the child with epilepsy (Baker et al., 2008; Ramaglia et al., 2007). Some family members appear to be more at risk for a negative emotional impact. The emotional impact on parents of younger children, unmarried parents, and parents of children and adolescents who have both epilepsy and comorbidities have been shown to produce a rela-

tively poorer quality of life (Taylor et al., 2011a). In one of the few studies comparing mothers and fathers, mothers were found to bear more of the responsibility for caregiving and also to experience more anxiety and strain, as well as more worry about the stigma associated with epilepsy (Ramaglia et al., 2007). A study of caregivers determined that women caregivers over age 60 who were the only person responsible for giving medication experienced the greatest impact on their quality of life (Westphal-Guitti et al., 2007). Other factors described as contributing to increased depression were lack of emotional and practical support (Thompson and Upton, 1992), loss of sleep (Modi et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2008), and financial burden (O’Dell et al., 2007b).

All members of the family appear to be at risk for psychosocial problems (Ellis et al., 2000). Although understudied, children who watched their parents have a seizure were often confused and frightened that their parent might die. These children also experienced fear of abandonment when parents were hospitalized (Lannon, 1992). This finding is consistent with a survey reporting that parents with epilepsy worried about their children becoming upset from witnessing them have a seizure (Fisher, 2000). In a recent study, siblings expressed sadness, fear, anxiety, and worry about their brothers and sisters with epilepsy. Some siblings also reported they were worried because their parents were so exhausted, and they often felt lonely because the parents were so busy caring for their sibling with epilepsy (Hames and Appleton, 2009).

Impact on Family Social and Leisure Activities

Family social and leisure activities are often restricted because of epilepsy (Ellis et al., 2000; Taylor et al., 2011a). Parents of children with epilepsy were found to spend less time outside the home on recreational activities than controls (Modi, 2009), to rate their quality of life lower in the areas of impact on their time and on family activity (Taylor et al., 2011a), and to lack time to pursue personal interests (Lv et al., 2009). Families of adults with refractory seizures reported restricted social lives (Thompson and Upton, 1992).

Challenges that affect quality of life for families and may lead to restrictions on social and outside family activities include the need to provide caregiving, the lack of support from outside the family unit, inadequate support from extended family members, and a lack of awareness about the resources available (Ellis et al., 2000; Saburi, 2011; Thompson and Upton, 1992). Ellis and colleagues (2000) suggested that the lack of family activities might indirectly contribute to the increase in emotional difficulties experienced by family members, because participation in leisure activities can help buffer against stress and family demands.

Impact on Employment and Role Expectations

A third area in which the quality of life of family members is affected relates to employment and the disruption in meeting role expectations. Parents reported that epilepsy had a negative effect on employment, with many parents missing work due to caregiving responsibilities (Lv et al., 2009). In a survey of families from 16 countries, Baker and colleagues (2008) found that many parents needed to take time off from work because of epilepsy, and some parents gave up their jobs to care for their child. In a 12-month study of the impact of epilepsy on parents, Ramaglia and colleagues (2007) found that 33 percent of mothers and 7 percent of fathers left their jobs temporarily. One year later, all fathers were back at work; however, 16 percent of mothers were still not working. In a study of caregivers of adolescents and adults, caregivers reported that the negative impact of epilepsy (e.g., emotional challenges) was a burden that affected and interfered with their ability to work and participate in other activities. In this study, women were more likely to be caregivers and more likely to experience these burdens (Westphal-Guitti et al., 2007).

In some families, disruption of roles reduced the quality of life of family members. Lannon (1992) found that children of parents with epilepsy sometimes experienced a reversal of roles, when they felt the need or were asked to take on adult responsibilities. Siblings of children with epilepsy also reported that their activities were disrupted because of caregiving responsibilities (Hames and Appleton, 2009).

Improving Programs and Services for the Family

Many of the authors whose research is discussed above identified resources and services that could help reduce the negative impact of epilepsy on the quality of life of family members. However, family members may be unaware of available community services. Health care providers should routinely provide information about community resources and support services to all families, and state and local Epilepsy Foundation affiliates and other epilepsy-specific organizations should be an integral part of discussions with individuals with new-onset epilepsy and their families to help direct them to needed community services. Access to a 24-hour, nonmedical help line could be a valuable source of information if broadly marketed, as could in-depth websites (Chapter 7). Strategies for building social support networks could be encouraged (Rodenburg et al., 2007); for example, joining with families in similar situations for leisure and social activities. Sharing experiences through online social networks with people facing similar issues also can provide needed support (Wicks et al., 2012).

Because the negative emotional effects from epilepsy can affect family functioning and quality of life, health and community service professionals

should provide families, especially parents, with information on strategies to help reduce family stress and successfully cope with epilepsy (Rodenburg et al., 2007). For example, Hames and Appleton (2009) identified a need for materials that are specifically developed for siblings. Family members also could benefit from support groups and counseling. In the survey by Baker and colleagues (2008), 36 percent of families had consulted an epilepsy counselor.

Seeking respite care is an important strategy, particularly for families of individuals with uncontrolled seizures or serious comorbidities. These families also could benefit from the availability of respite and day care services (Thompson and Upton, 1992). These services, if available, could reduce the caregiving burden and provide opportunities for families to have time to participate in social activities or pursue personal interests. An extended family network could serve a similar function, but for unknown reasons, it appears that many families do not receive support from extended family members (Saburi, 2011). Research is needed to identify barriers to receiving support and assistance and strategies for overcoming those barriers. Public awareness campaigns may be able to disseminate information about how people with epilepsy and their families need the support of extended family members and friends. Future research that focuses on multiple members in each family would provide important information about which family members are most in need of resources and support.

[Our son] has tuberous sclerosis complex and epilepsy and he has had seizures since birth…. At age 2, Evan was placed into early intervention services in our county, and he was evaluated for special education, which included being placed on an individualized education program (IEP) when he was 3…. The IEP process empowers parents to be effective advocates for their children…. Through the IEP process [we] realized early on that many of the teaching staff were unfamiliar with epilepsy and apprehensive about caring for individuals with seizures. Included in his IEP was the request for seizure training for all staff members who would have [our son] in their care and that this training would occur prior to him entering kindergarten. We were under the impression this would involve a small meeting with … his teacher and possibly the school nurse. We walked to the library with the school principal, who was carrying a case of water, and we weren’t quite sure what we had gotten ourselves into! We learned that “staff caring for [our son]” included his teachers, the school health aide, PE and art teachers, office staff, librarians, and the list goes on. We meet with 25 to 30 staff members yearly to describe [our son’s] typical seizures and how they may affect his ability to perform in the school setting. The staff has a separate training performed by the county nurse and are required to review a seizure training video created by the

national Epilepsy Foundation…. We expect that by the time Evan exits elementary school, over 100 teachers and staff will have received extensive seizure training, and many teachers will have had annual refreshers. But this is just [one] school, and training like this needs to be expanded to all schools nationwide.

-Lisa and Robert Moss

Although most children with epilepsy do not have cognitive disabilities, as a group, children with epilepsy are at a greater risk of developing learning problems and of academic underachievement (Fastenau et al., 2008). One reason for this increase is that intellectual disability is a risk factor for developing epilepsy (Chapter 3). However, even children with epilepsy who do not have intellectual disability are at increased risk for learning and academic problems (Fastenau et al., 2008), as well as for psychosocial problems later in adolescence and adulthood (Sbarra et al., 2002). The age of onset of epilepsy is associated with effects on intelligence (Bjørnaes et al., 2001; Bulteau et al., 2000; Cormack et al., 2007; Hermann et al., 2002), learning (Fastenau et al., 2008; Sillanpää, 2004), social outcome (Lindsay et al., 1979; Sillanpää, 1983), and medical refractoriness (Berg et al., 1996; Camfield and Camfield, 2007; Casetta et al., 1999). Children who achieve seizure control relatively early in the course of epilepsy and have few cognitive impairments can attain average or above-average educational achievement. As described below, these learning, academic, and cognitive problems can result in the need for an array of support services in day care and school.

Early Childhood and Day Care

In the United States, more than 11 million children under 5 years of age are in some form of day care (professional or home) each week (NACCRRA, 2011). The paid early childhood care and education workforce in the United States is estimated at 2.2 million individuals, with approximately one-fourth caring for infants (IOM and NRC, 2011). Although little is known about the extent to which day care providers are aware of epilepsy and the range of types of epilepsy that could affect young children, there are concerns that some child care providers may refuse to accept a child with epilepsy based on their misconceptions about the disorder and about the amount of attention a child with epilepsy may need (Epilepsy Foundation, 2010).

Child care workers’ training and qualifications vary widely, with each state having its own requirements (BLS, 2009). Requirements range from less than a high school diploma to a college degree in child development or early childhood education. Requirements are generally higher for workers at child care centers compared to those for family child care providers (BLS,

2009). An increasing number of child care employers require an associate’s degree in early childhood education as a minimum requirement; however, only 12 states require training in early childhood education before leading a classroom in a child care center (BLS, 2009; NACCRRA, n.d.). As noted later in the chapter, first aid training is a requirement for many day care providers, and well-established first-aid courses (e.g., Red Cross training) provide education on how to recognize and respond to seizures. Further efforts to identify the educational needs and the knowledge and attitudes of day care staff regarding epilepsy are necessary. Such research would inform the development of guidelines and educational programs.

Additionally, parents of children with epilepsy can play an important role as advocates for training of their child’s day care providers (Epilepsy Foundation, 2010). As parents take on the role of advocate they can be supported by state and local Epilepsy Foundation affiliates and other nonprofit organizations through parent support groups; these organizations can provide written materials on epilepsy that parents can supply to their day care providers and other supporting efforts.

School

School and Academic Achievement

A major developmental task for all children is to achieve success in school. On average, school-aged children and youth spend about half of their waking hours at school. Although many children and youth with epilepsy do well in school and do not have cognitive disabilities, as a group they are relatively more likely to have learning and achievement problems, to have cognitive deficits, and to need special services. Parents report that communication and interactions with school personnel when seeking help for their children are major sources of family stress (Buelow et al., 2006).

Learning disabilities1 often are part of the school challenge for children with epilepsy. In a study of children and adolescents with epilepsy, 48 percent had a learning disability in at least one academic area using an IQ achievement discrepancy definition, and 41 to 62 percent had a learning disability using a low-achievement definition (Fastenau et al., 2008). In a recent study of special school services for children with epilepsy who had an IQ of at least 80, 45 percent used special education services, and 16 percent had been held back a year (Berg et al., 2011). In comparison studies, children with epilepsy demonstrate more cognitive deficits and academic

_______________

1Learning disabilities are defined as disorders in the basic psychological and neurological processes involved in understanding or using language, spoken or written, that may manifest themselves in an imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or use mathematical calculations.

problems than their healthy siblings (Berg et al., 2011; Dunn et al., 2010), healthy controls (Oostrom et al., 2003), and children with another chronic condition such as asthma (Austin et al., 1998, 1999). Poor achievement has generally been found in all academic areas (Austin et al., 1998; Fastenau et al., 2009; Sturniolo and Galletti, 1994).

Academic problems have been found to precede seizure onset in 15 to 24 percent of children with epilepsy (Berg et al., 2005, 2011). One of the risk factors for academic underachievement is poor cognitive functioning (Dunn et al., 2010; Fastenau et al., 2004; Schouten et al., 2002). Other risk factors include younger age of seizure onset (Dunn et al., 2010; Schoenfeld et al., 1999; Seidenberg et al., 1986), more frequent seizures or more severe seizure conditions (Austin et al., 1998, 1999; Berg et al., 2005; McNelis et al., 2007), presence of comorbidities such as ADHD (Fastenau et al., 2008), and psychosocial adjustment problems (Sturniolo and Galletti, 1994).

A supportive family environment and certain caregiver characteristics can be protective factors for children with epilepsy and can buffer the effect of poor cognitive functioning on academic achievement. For example, one study found that children with cognitive problems who lived in more supportive and organized family environments had better academic achievement than those who lived in less supportive, more disorganized homes (Fastenau et al., 2004). In a recent prospective study investigating the effect of cognitive functioning on academic achievement in children with epilepsy, Dunn and colleagues (2010) found that a higher education level of the caregiver was associated with better academic achievement and that greater caregiver anxiety was associated with lower academic achievement. These findings suggest that community support resources to help parents reduce their anxiety and create more supportive environments might also help their children in school.

The high prevalence of cognitive deficits consistently found in children with epilepsy, along with the negative impact of those deficits on academic achievement, make it imperative that children with epilepsy be screened early for cognitive problems and that early interventions be developed and applied (Fastenau et al., 2009). In addition, because children with epilepsy often have the inattentive form of ADHD (Dunn et al., 2003), which is associated with poorer academic achievement (Fastenau et al., 2008; Hermann et al., 2008), they also should be screened routinely for ADHD. Such assessments may occur as part of diagnostic testing at the time of epilepsy onset (depending on the age of the child when first diagnosed), but must be repeated regularly. Screening for cognitive problems and ADHD is important for adolescents as they transition to post–high school education and enter the workforce, so that they can identify and access programs and services to help meet their needs or seek accommodations at college

or in their work. Neuropsychological testing is a critical tool for identifying major learning impairments in children with epilepsy as well as diffuse mild cognitive impairments often missed in standardized school testing. Results and recommendations from these tests are used in developing IEPs and other educational plans and are also important in helping adolescents and young adults identify independent living needs and skills and assist in planning their future.

Unfortunately, currently there is no quick psychometric screen for assessing cognitive functioning for epilepsy, and research is needed that would enable the development of a tool to help identify children at risk for academic achievement problems. Further, the committee found few studies that tested programs that would help children with epilepsy improve their learning skills. A promising Direct Instruction2 program was piloted with children who had poor seizure control and learning difficulties in a classroom at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto (Humphries et al., 2005). Prior to entering a program up to 16 weeks in duration, children completed placement tests to identify their academic needs. All staff members were trained in Direct Instruction, there were no more than eight children in a classroom, and the educational program was delivered using standardized methods. Instruction was provided in a range of areas, including reading, reasoning and writing, math concepts, language, and spelling. Following the completion of the program, significant improvement was found in all academic areas except word identification in reading. The authors concluded that Direct Instruction can help children with epilepsy close gaps in learning skills that will provide a good foundation for learning. More research is needed to develop screening tools for assessing cognitive functioning in children with epilepsy, to evaluate programs to improve learning problems they experience, and to implement effective programs more widely.

School Personnel

The attitudes of teachers and other education providers (including day care providers) toward epilepsy can significantly influence students’ school performance and social skill development (Bishop and Slevin, 2004). Teachers play an important role in the health care of children with epilepsy, in that they are frequently in the best position to observe a child for possible seizures or adverse medication effects during the day. However, students

_______________

2Direct Instruction is a highly structured approach to teaching designed to facilitate learning among students with various learning problems. The method focuses on making material as clear as possible and building toward more complex ideas and skills. See, for example, http://www.promisingpractices.net/program.asp?programid=146.

with epilepsy can be at increased risk for social and academic problems if their teachers have misperceptions or a lack of information about epilepsy, or if they perpetuate the stigma often associated with the disorder (Chapter 8) (Bishop and Slevin, 2004; Dantas et al., 2001).

In several studies, teachers report little confidence in instructing students with epilepsy and acknowledge that they have limited information about the disorder, how best to work with students with epilepsy, or how to respond to seizures if they occur in the classroom (Bannon et al., 1992; Bishop and Boag, 2006; Bishop and Slevin, 2004; Wodrich et al., 2011). Further, teachers appear unlikely to actively seek information about epilepsy (Bishop and Boag, 2006). Changes may be under way in some schools as a result of a recent evaluation that found teachers who were currently teaching a child with epilepsy appeared to have more school-relevant epilepsy facts than teachers generally, and they expressed greater confidence in their ability to meet these students’ instructional, safety, and psychosocial needs (Wodrich et al., 2011).

Effective programs for educating and increasing student, teacher, school nurse, counselor, and parent awareness are critical. The Epilepsy Foundation has developed programs and resources to educate teachers and to help them increase epilepsy awareness in their classrooms. For example, the website-based program, Epilepsy Classroom, developed by UCB, Inc., in collaboration with the Epilepsy Foundation, provides lesson plans, classroom resources, and parent resources on a range of topics relevant to children with epilepsy in the school setting (Epilepsy Classroom, 2012). Several studies have shown that even brief, focused interventions in educational settings can produce improvements in epilepsy-related knowledge and attitudes among students (Fernandes et al., 2011; Martiniuk et al., 2007; Roberts and Farhana, 2010). However, teacher-focused research is limited; teacher-focused interventions need to be developed and tested; and increased education about epilepsy is needed in teacher preparation programs (Bishop and Boag, 2006) and in continuing education for school nurses, counselors, and other school personnel. Efforts are needed to design, implement, and evaluate interventions for school settings that build on techniques and methods that have been evaluated and found to be effective.

Legal Mandates

Access to special education services or other educational supports may be mandated or otherwise available for children with epilepsy as a result of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (reauthorized most recently in 2004, P.L. 108-446) and the 1973 Rehabilitation Act (P.L. 93-112) and its amendments (U.S. Department of Justice, 2005). IDEA and its

amendments mandate free and appropriate public education for all students with disabilities through age 21 or high school graduation; require that school districts identify, evaluate, and reevaluate children who need special education and related services; stipulate that education should be provided for students in the least restrictive environment and alongside of students without disabilities whenever possible; and mandate nondiscrimination in testing and evaluation services for children with disabilities. The legislation specifies the rights and processes for the development of an IEP for each student enrolled in special education and individualized transition planning to prepare special education students for post-school environments (Box 6-2). Students with disabilities who do not qualify for an IEP but have a disability and require reasonable accommodation while attending school may have an educational plan under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Section 504 regulations require a school district to provide qualified students with a disability a “free appropriate public education” regardless of the nature or severity of the disability. Further, nondiscrimination is mandated; students with disabilities must not be excluded from nonacademic activities, such as athletics, transportation, health services, recreational activities, and special interest groups or clubs. Students qualifying for protection under Section 504 include those who have been identified as having a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities (U.S. Department of Education, 2011a).

Box 6-2 EDUCATIONAL PLANS FOR STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES

Individualized education program (IEP) An IEP is a multipart written statement for the child with a disability that includes information on annual academic and functional goals, plans on how progress will be measured on those goals, details on the special education and related services to be provided to the child, and information on any appropriate individual accommodations necessary to measure the academic achievement and functional performance of the child on state- and district-wide assessments (U.S. Department of Education, 2011b). By the time the student reaches 16 years of age, the IEP must include a discussion of postsecond-ary goals and transition services needed (U.S. Department of Education, 2011c).

Section 504 educational plan Students with disabilities who do not have an IEP can have a Section 504 educational plan that outlines the educational ser-vices and accommodations necessary to ensure equal access to education (U.S. Department of Education, 2011a). Accommodations may include, for example, schedule modification, a structured learning environment, modified test instructions and test delivery, and assistive technology and medical and transportation services. Section 504 plans also allow for any necessary and related services as occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech and language services.

The 2008 amendments to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) expanded the definition of major life activities to include learning, reading, concentrating, and thinking, as well as expanding the definition to include neurological and brain functions (U.S. Access Board, 2008). The amendments also clarified that the act covers impairments, such as epilepsy, that are episodic in nature or in remission and that substantially limit a major life activity when not in remission (U.S. Access Board, 2008). Epilepsy advocates and numerous other disability advocacy groups were active in supporting and informing these changes.

Improving School and Day Care Programs

A large part of improving school and day care services for children with epilepsy revolves around enhancing teachers’ awareness about epilepsy and developing an educational plan focused on meeting students’ individual needs. Although not all children and youth with epilepsy require specialized services, these services must be available for those that do, so that all students have opportunities to reach their full potential. The committee believes that teachers, counselors, day care providers, and school personnel working with children with epilepsy have the responsibility to become informed about the disorder so that they can work effectively with parents and students to develop tailored educational plans. Additionally, the committee recognizes that parents may have to be active advocates for their children in the development and implementation of educational plans. Parents and school staff can encourage students with epilepsy to reach out to peers and teachers for help with accommodations as needed and help students become strong and informed self-advocates.

Physical activity and recreation are important components of physical and emotional well-being and quality of life for all people, and people with epilepsy are encouraged to be as physically active as possible (Epilepsy Foundation, n.d.; Howard et al., 2004). Obesity and being overweight are a concern for people with epilepsy because studies have found that children with newly diagnosed, untreated epilepsy have higher body mass index levels than children in a comparison cohort and that women with epilepsy have a higher body fat ratio than healthy controls (Daniels et al., 2009; Howard et al., 2004). A population-based study using the Canadian Community Health Surveys between 2001 and 2005 found that individuals with epilepsy were 1.4 times more likely to be physically inactive than the general population (Hinnell et al., 2010). In addition, some seizure medications have been associated with weight gain (Ben-Menachem, 2007; Biton, 2003;

Verrotti et al., 2011). Although exercise-induced seizures are rare, factors that may exacerbate seizures include hyperventilation, fatigue, altering levels of metabolism of seizure medications with exercise, psychological stress, and increased heart rate during intense activity (Dubow and Kelly, 2003; Fountain and May, 2003; Howard et al., 2004; Sahoo and Fountain, 2004).

However, research in sports and exercise suggests that regular physical activity—in addition to its well-known positive psychosocial and physiologic benefits—can reduce the frequency and severity of seizures among children and adults, including women (Arida et al., 2009, 2010; Conant et al., 2008; Eriksen et al., 1994; Nakken et al., 1990, 1997). A survey of Norwegians with epilepsy, for example, found that exercise was associated with better seizure control (Nakken, 1999). Physical activity also can improve attention, mood, and physical health and may have a role in minimizing depression in people with epilepsy (Arida et al., 2012). Although some seizure medications can affect bone density, which peaks in adolescence and has consequences in adulthood related to risks for fractures and osteoporosis (Pack, 2011; Pack and Morrell, 2004; Samaniego and Sheth, 2007), participation in regular weight-bearing activities in conjunction with adequate calcium consumption and vitamin D can mediate the process of bone loss (HHS, 2004).

A few studies have examined the extent to which people with epilepsy engage in sports and recreational activities or experience limitations in their activities. The 2003 California Health Interview Survey found that adults who have had epilepsy reported twice as many activity limitation days as those without (Kobau et al., 2007). In a study comparing siblings with and without epilepsy, no significant differences were seen for physical activity in children under 12 years, but youth ages 13 to 17 years participated less frequently in group sports and total sports activities, although participation in individual sports was similar (Wong and Wirrell, 2006).

Researchers found that Canadians ages 12 to 39 spent similar amounts of time in leisure physical activity regardless of whether they had epilepsy or not; they noted that people with epilepsy reported more walking and were less likely to be involved in ice hockey, weight training, or home exercise (Gordon et al., 2010). A study in South Korea evaluated active and inactive individuals with epilepsy to identify barriers to exercise (Han et al., 2011). Anxiety, taking multiple seizure medications, and previously experiencing a seizure during exercise were significantly associated with inactivity. In addition, fear of participation, overprotection, and discouragement from family, friends, or physicians were significant barriers. Other barriers in the study included fatigue following activities, the lack of an exercise partner, limited time, and uncertainty of how to begin and continue an exercise program.

Recommendations on participation in sports by people with epilepsy have changed over the years. The 1968 American Medical Association

Committee on Medical Aspects of Sports opposed participation in collision and contact sports by individuals with epilepsy, but by 1978 the committee had reversed that recommendation, and its 1983 statement urged full participation in physical education programs and interscholastic athletics, aided by common sense and proper supervision (Dubow and Kelly, 2003). Further research is required to understand the effects of intense exercise and the effect of exercise and sports on metabolism of seizure medications. In addition, research is needed to understand the effect of epilepsy and seizures on aerobic endurance and balance.

Selection of sports and leisure time activities for children and adults with epilepsy involves consideration of personal preferences, the nature of the sport, the risk of injury, and individual factors regarding seizure type, frequency, and severity (Drazkowski and Sirven, 2011; Dubow and Kelly, 2003; Fountain and May, 2003). Since rates and degree of injuries during participation in contact sports are similar between people with and without epilepsy, participation in contact sports is an option (Miele et al., 2006). Recommendations for athletes with epilepsy in competitive sports, contact sports, and high-risk sports include the need to receive an initial neurological evaluation to establish a baseline and another after any injuries, to adhere to prescribed medication regimens, to inform the team manager or coach about epilepsy, and to use adequate protective equipment (Dimberg and Burns, 2005). Table 6-3 provides a general categorization of sports and activities by risk.

One way to encourage exercise, skill development, and independence for children with epilepsy is through residential camps that either are specifically focused on this disorder or more broadly serve children with various serious or chronic health conditions. These types of camps offer opportunities for children to learn about self-management and interact with other children and youth who share similar experiences. Studies of health condition-specific camps found improvements in participants’ attitudes about their health condition and quality of life and reduced anxiety (Bekesi et al., 2011; Briery and Rabian, 1999). Similarly, in a 3-year study that examined adaptive coping behavior in campers at an epilepsy-specific summer camp, significant improvements were observed for return campers in communication, responsibility, and social interactions (Cushner-Weinstein et al., 2007). Many nonprofit organizations, including state and local Epilepsy Foundation affiliates, offer information on and opportunities for summer camps and other recreational activities (Epilepsy Foundation, 2011; Epilepsy.com, 2011).

Expanding participation in sports and other recreational activities will involve continued efforts to increase awareness that people with epilepsy can and should be physically active. Further, coaches, workout instructors, counselors, camp directors, and others in the physical activity and recre-

TABLE 6-3

Sporting and Recreational Activities Classified According to a Possible Risk for the ndividual with Epilepsy

| Low Risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk |

| Baseball | Basketball | Boxing |

| Bowling | Biking | Downhill skiing |

| Cross-country skiing | Boating or sailing | Gymnastics (equipment with height) |

| Golf | Football | |

| Ping-Pong | Gymnastics (floor) | Hang gliding |

| Track | Horseback riding | Hockey |

| Walking | Karate | Motor sports |

| Weight training (machines) | Skateboarding | Rock climbing |

| Yoga | Soccer | Scuba diving |

| Swimming Waterskiing | Swimming (long distance) | |

SOURCE: Adapted from Drazkowski and Sirven, 2011. Reprinted with permission from Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, http://www.lww.com.

ation fields need up-to-date information about epilepsy. Methods for most effectively providing this information need to be explored. Nonprofit organizations and the public health community can disseminate information tailored to meet this need. Individuals, parents, and caregivers should be sure that those with whom they work and who coach children and youth with epilepsy are fully aware of any specific limitations. As discussed later in the chapter, seizure first aid training is critically important.

By the time I was in high school, everybody knew I had epilepsy, and it was not really a big deal…. But then one day I decided I wanted a job…. Now, this was 1972, [and] the application looked more like a new patient intake form. It actually listed a huge long list of medical disorders, and one of them was epilepsy. I was telling everybody I had epilepsy, so I marked it. And so I took my little application up, handed it in at the window, and the person there right in front of me picks up a red pen and makes circles where I checked I had epilepsy. They did not call me for an interview. So the next day I went to another store. I saw they had a “help wanted” sign. And I filled out the application, and they did not ask for specifics, but there was a health-related question. And right there, 18 years before Congress, I enacted my own Americans with Disabilities Act. I had two qualifications. One, could I do the job and, two, if I did have a seizure, would somebody else get hurt? If I got hurt, well, couldn’t do anything about that. Since then I have never put epilepsy on the application.

-Mary Macleish

Employment is a critically important aspect of quality of life and psychosocial health, providing avenues for social participation, economic security (Bishop and Chiu, 2011), and for many people in the United States with epilepsy, access to health insurance. For some people with epilepsy, transportation to and from work poses major challenges to gaining and maintaining employment.

Although most people who have epilepsy are able to fully participate in the labor market, they consistently have higher levels of unemployment compared to the general population (Bishop, 2002; Fisher, 2000; Kobau et al., 2008; Smeets et al., 2007). Further, they are more likely to be employed in unskilled and manual jobs or underemployed (employed in a job where they have more skill, education, or training than what is required, which results in their earning capacity not being met) (Bishop and Chiu, 2011; Smeets et al., 2007). Although the lack of standard definitions makes the measurement of employment, unemployment, and underemployment a complex and inexact science (Chaplin, 2005), research using population-based samples has consistently suggested that the unemployment rate of people with epilepsy is at least twice that of the general population (Fisher, 2000) and even higher among people who seek care in tertiary care centers, which is often those individuals with more severe types of seizures (Hauser and Hesdorffer, 1990; Thorbecke and Fraser, 2008).

Available evidence underscores consistent and persistent employment problems for people with epilepsy. Responses to a community-based survey of adults with epilepsy indicated that 25 percent of eligible workers reported being unemployed at a time when the average unemployment rate in the United States was slightly more than 5 percent (Fisher et al., 2000). Data from the 2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys, which included population data from 19 states, suggested that the unemployment rate was 9.8 percent for people with active epilepsy,3 8.3 percent among those with inactive epilepsy, and 5.4 percent for those with no epilepsy history (Kobau et al., 2008). Nine-state data from the 2006 BRFSS indicated that people with a lifetime prevalence of epilepsy3 were more than three times as likely to be unemployed or unable to work as people who did not have epilepsy (34 percent versus 9 percent), and people with active epilepsy were more than four times as likely to be unemployed or unable to work in a similar comparison (42 percent versus 9 percent) (Konda et al., 2009). Although estimates of the extent of employment disparities vary based on methodology and sample characteristics, relatively lower levels of employment have been consistently found for people with

_______________

3In both studies analyzing the BRFSS results, active epilepsy was defined as having 1 or more seizures in the past 3 months or taking medication for seizure control, and lifetime prevalence of epilepsy was defined as responding affirmatively to ever being told by a physician that they had a seizure disorder or epilepsy (Kobau et al., 2008; Konda et al., 2009).

epilepsy for more than three decades (Bishop, 2002). Employment disparities have continued despite improvements in clinical treatment and laws protecting the employment rights of people with disabilities (Jacoby et al., 2005).

The apparently difficult employment situation for people with epilepsy is not reducible to a single factor, such as the experience of seizures, but rather represents a complex interaction of variables (Thorbecke and Fraser, 2008). A variety of seizure-related factors (e.g., seizure frequency, type, perceived impact, felt stigma) have been shown to predict employment status, as have the age of epilepsy onset, comorbid mental health and cognitive conditions, the adverse effects of seizure medications, and various psychological factors, such as depression and anxiety (Bishop, 2004; Chaplin et al., 1998; Jacoby et al., 1996, 2005; Rätsepp et al., 2000; Yagi, 1998). Psychosocial factors relevant to unemployment rates among people with epilepsy include social isolation, social skill deficits, low self-esteem, lack of family support, and fears about negative attitudes on the part of employers (e.g., Smeets et al., 2007; Thorbecke and Fraser, 2008). External factors, such as enacted stigma and discrimination, also contribute to employment problems for people with epilepsy, and the effects of these may be more significant in times of high unemployment, when competition for jobs is heightened (Jacoby et al., 2005).

In the employment application process, deciding on the appropriateness and necessity of openness about the epilepsy diagnosis “may be influenced by legal, medical, social, and personal concerns” (Bishop and Chiu, 2011, p. 100). People with epilepsy may need to be open in acknowledging that they have epilepsy if they need work-related accommodations. If accommodations are not required and the applicant can perform the required duties of the position, then openness about the diagnosis may not be necessary (Bishop et al., 2007). In general, however, opinions vary about the advisability of disclosure. In a survey of state and local Epilepsy Foundation affiliates, none of the organizations reported that they counsel people to be open about their condition either on applications or in initial interviews, and more than half of respondents indicated that if an open discussion about the condition is necessary, they would advise that it be done after being hired (Bishop and Allen, 2001). By contrast, in a survey of employers by Jacoby and colleagues (2005), a majority of employers indicated that prospective employees with active epilepsy (defined as “currently having seizures, even if only occasionally,” p. 1981) should discuss their disorder openly, preferably early in the recruitment process, even if seizures are well controlled. As the researchers noted, “There is a clear mismatch between the position of employers, who may see non-disclosure as a breach of trust, and [people with epilepsy], many of whom opt not to disclose out of fear of enacted stigma” (Jacoby et al., 2005, p. 1984).

Employer attitudes can be a significant barrier to employment (Bishop, 2002; Bishop and Chiu, 2011; Epilepsy Foundation, 2001; Jacoby et al., 2005). Researchers have found that employers’ attitudes regarding employment of people with epilepsy include concerns about the comfort and safety of workers, worries about increased accident rates and subsequent increases in insurance rates, and questions about the need to revise work flows with possible increases in expenses for work-related accommodations (e.g., Bishop et al., 2007; Hicks and Hicks, 1991; Jacoby et al., 2005; John and McLellan, 1988). However, there is no empirical support for these concerns (Jacoby et al., 2005).

In the past several decades, survey research has found improving attitudes toward people with epilepsy (Chapter 8). However, contrasting data have been reported by researchers who used indirect survey methods that are less susceptible to socially desirable responses (Antonak and Livneh, 1995; Baumann et al., 1995; Bishop and Slevin, 2004) and by evidence that the level of unemployment for people with epilepsy and employers’ attitudes have remained fairly constant over a 30-year period (Bishop, 2002; Jacoby et al., 2005). Based on their 2005 survey of a representative random sample of UK employers, Jacoby and colleagues found that 26 percent of employers reported having employed individuals with epilepsy knowingly; 16 percent believed their company had no jobs suitable for individuals with epilepsy; 21 percent thought employing people with epilepsy would be “a major issue”; and epilepsy created high concern for around half (in part because of concerns about work-related accidents), although they said they were willing to make accommodations for people with epilepsy. Further, a U.S. study among employers and human resources personnel suggested that hiring an individual with epilepsy was less likely than hiring people with any number of other disabilities, including cancer in remission, depression, a history of heart problems, AIDS, mild intellectual disabilities, and spinal cord injury (Bishop et al., 2007).

Attitudes of employers toward hiring people with disabilities generally differ depending on the ways in which attitudes are defined and measured, as well as the size of the employer and the employer’s experience with previous hires. Positive attitudes tend to be found in studies that assessed general, as opposed to specific, attitudes and situations involving workers with disabilities. Further, although employers may have positive attitudes toward workers with disabilities, those attitudes do not always translate into active efforts to employ people with disabilities (Hernandez et al., 2000). In surveys of employers, those from large companies were more likely to have positive attitudes about workers with disabilities; to hire more workers with disabilities, including workers with epilepsy (Jacoby et al., 2005); and to have made worksite accommodations (Bruyère et al., 2003; Lee, 1996).

Larger companies were also more likely to be familiar with employment-related legislation such as the ADA (Bruyère et al., 2006).

Potential avenues for improving employment opportunities for people with epilepsy include employer education programs and awareness campaigns, vocational rehabilitation programs and career services, and enforcement of antidiscrimination and equal opportunity legislation.

Employer Education Programs

Several public education efforts have been specifically directed at employers. For example, the Epilepsy Foundation has developed and sponsored employer education and awareness campaigns and developed and disseminated other materials to promote the hiring of people with epilepsy. During Epilepsy Awareness Month, efforts have been made to educate employers about the nature of epilepsy, its successful treatment, workplace accommodations, and vocational rehabilitation for people with epilepsy. Although epilepsy education campaigns and interventions have been shown to have positive effects in promoting knowledge and attitude change in educational, health, and more general settings (e.g., Martiniuk et al., 2010; Roberts and Farhana, 2010) (Chapters 5 and 8), the number of such efforts with an employment focus has been small, and evaluations of their efficacy in the research literature are scarce.

In a study examining the impact of an epilepsy education campaign in one U.S. city that focused on the mass media, community organizations, and mailings to selected employers, Sands and Zalkind (1972) did not find differences between pre- and post-campaign attitudes. However, understanding of the techniques that increase the effectiveness of public education campaigns has evolved considerably since 1972. Further efforts are needed to design, implement, and evaluate the efficacy of focused campaigns aimed at promoting employer knowledge and attitudes.

Workplace Programs

To improve employment opportunities, research has consistently pointed to the need for effective employment training programs for people with epilepsy (Smeets et al., 2007). A two-pronged approach has been supported for epilepsy vocational rehabilitation, one focused on specialized vocational rehabilitation services and the other focused on targeted epilepsy training for staff of broader vocational rehabilitation programs (Fraser, 2011).

Specialized employment programs and resources specifically for individuals with epilepsy have proved successful. These include the now discontinued TAPS (Training Applicants for Placement Success) and Job-

Tech programs (Bishop and Allen, 2001; Thorbecke and Fraser, 2008). Ongoing employment services provided by the Epilepsy Foundation include an online career support center, the Jeannie Carpenter Legal Defense Network (whose work includes employment discrimination), and employment-related services offered by state and local Epilepsy Foundation affiliates across the country (Fraser, 2011). The Epilepsy Foundation’s website includes an employment section that is designed to assist people with employment searches; in addition, the website provides guides on job preparation and job search sites, gives suggestions on ways to discuss information about epilepsy in the workplace, and offers other resources, including a discussion forum on epilepsy and employment (Epilepsy Foundation, 2012). The Epilepsy Foundation and its affiliates also organize employer education training and employer and employee awareness and training conferences that bring employers together with supporting and enforcement agencies, such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, to provide information on the rights of workers with epilepsy (Epilepsy Foundation Northwest, 2012).

General (not epilepsy-specific) employment services are available through state-federal vocational rehabilitation programs and One Stop Career Centers in each state (U.S. Department of Labor, 2012). Little research has evaluated the effectiveness of epilepsy and vocational rehabilitation programs (Smeets et al., 2007). However, programs that are focused on vocational rehabilitation for people with epilepsy appear to be more effective than general vocational rehabilitation programs (Fraser et al., 1984; Thorbecke and Fraser, 2008). For example, Fraser and colleagues (1984) reported that whereas general state vocational rehabilitation agencies achieved 9 to 21 percent placement rates among people with epilepsy, specialized vocational rehabilitation programs achieved placement for almost half of individuals, a finding reiterated in more recent research (Mount et al., 2005). These results may reflect both the focused delivery and the epilepsy knowledge of the professionals providing services. For example, the extent to which state-federal vocational rehabilitation programs hire master’s level and certified rehabilitation counselors varies by state.