5

Promising Practices in Addressing Social

Determinants: Obesity Prevention

Session chair Pattie Tucker of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) introduced the session on social determinants of health by indicating that the focus is on promising practices to address social determinants of health (in this case, obesity).

THE PRESIDENT’S TASK FORCE ON CHILDHOOD OBESITY

Susan Sher is an assistant to the president and chief of staff for First Lady Michelle Obama. In this role, she works closely with the First Lady and her staff on issues related to military families, national service, elimination of childhood obesity, and promotion of healthy living. Sher’s presentation focused on the First Lady’s Initiative to Combat Childhood Obesity, which is a component of the President’s Task Force on Childhood Obesity.

Sher stated that the United States faces a serious epidemic of obesity, with a well-documented rise in adult obesity levels occurring over the past 20 years. For children, obesity rates increased from 12 percent of all children to 33 percent of all children during that same time period. If these trends continue, more than 100 million American adults will be obese by 2018 (United Health Foundation, 2009). Furthermore, if the prevalence of obesity continues, the nation’s next generation will live shorter, sicker lives than their parents. This is because obesity plays a critical role in many diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, and certain types of cancer.

Data for a large racially and ethnically diverse population of 2- to 19-year-olds recently released by Kaiser Permanente indicate that 7.3 percent of boys and 5 percent of girls are extremely obese. These rates are even

higher for Latino teenage boys, at 11.2 percent, and for African American girls, at 12 percent (Koebnick et al., 2010).

Low-income families in every racial, ethnic, and gender group also have higher obesity rates. Sher acknowledged that the relationship between obesity and poverty is a complex one. However, “food deserts” (urban areas without access to fresh, healthy, and affordable fruits and vegetables) are one major reason for the linkage between impoverishment and obesity in disadvantaged areas. More than 23 million Americans—6.5 million of them children—live in low-income neighborhoods that are more than a mile from markets with access to fresh foods. This means that those communities that can least afford fresh foods end up bearing the brunt of the costs associated with obesity. Food insecurity and experiences of hunger among children in the United States are even more widespread, Sher said. A recent report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) showed that 17 million households experienced hunger multiple times throughout the year (Nord et al., 2009).

Obesity is also associated with more chronic conditions than either smoking or excessive drinking, said Sher, and by 2020 the United States is projected to spend over $343 billion on health care costs attributable to obesity. Today, spending attributable to obesity is approximately $150 billion.

However, the costs of obesity and obesity-related diseases are more than simply financial in nature. Obese people are more likely to experience social disengagement and have fewer opportunities in education and the workforce. Obese children tend to become sad, lonely, and more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors, such as smoking or drinking alcohol. Other data indicate that children’s body mass index (BMI) and level of physical activity within the school day affect their academic performance in both reading and math. Sher noted that the obesity problem has reached “epidemic proportions.”

Let’s Move

In response to the obesity epidemic, Sher highlighted First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move campaign to solve the problem of childhood obesity. As a mother struggling to balance a healthy lifestyle with her family’s hectic schedule, Mrs. Obama is committed to reaching the national target of eliminating childhood obesity within a generation. Let’s Move is a comprehensive collaborative and community-oriented initiative that includes strategies to address the various factors that lead to childhood obesity (The White House, 2010). By fostering collaboration among leaders in government, science, business, education, athletics, and community

organizations, the goal is to create practical tools tailored to children and their families facing a wide range of challenges and life circumstances.

The Let’s Move campaign has four pillars. The first pillar is “empowering parents to make healthy family choices.” With acknowledgment that parents play a key role in making food choices for their children, part of this pillar is to create or redesign tools to educate parents across communities to make healthy food choices. By working with different food industries, Sher said, the Task Force on Childhood Obesity is trying to improve product labeling regulations to make it easier to read food labels. At the same time, USDA has created the Food Environment Atlas (www.ers.usda.gov/foodatlas), a database that maps the components of healthy food environments down to the local level across the country. For example, this system can help identify areas that are food deserts and areas with a high incidence of diabetes.

The second pillar is “serving healthier foods in schools.” This is an essential component of the campaign because many disadvantaged students consume 50 percent or more of their daily calories at school through the National School Lunch Program and the National School Breakfast Program. More than 31 million children participate in the lunch program, and more than 11 million participate in the breakfast program. One component of this pillar is to increase the number of schools participating in the Healthier U.S. Schools Challenge Program. The program establishes rigorous standards for school food quality, meal programs, physical activity, and nutritional education.

The third pillar is “increasing access to healthy, affordable foods.” An important component of this pillar is the establishment of a new program, the Healthy Food Financing Initiative. A partnership between the U.S. Departments of the Treasury, Agriculture, and Health, the initiative will invest $400 million per year to provide financing to bring grocery stores and farmers markets to underserved areas. Financing will also help corner grocery stores, convenience stores, and bodegas to carry healthier food options. Moreover, grants will be available to bring farmers markets and fresh foods into underserved communities. For example, in Philadelphia, a public-private partnership1 led to the opening of a huge new grocery store in an underserved area.

The last pillar is “increasing physical activity.” In disadvantaged neighborhoods, however, promotion of physical activity faces numerous challenges. For example, violence contributes to the lack of safe spaces for

![]()

1 Public-private partnership between the Food Trust and the Greater Philadelphia Urban Affairs Coalition is managed by The Reinvestment Fund, known as Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative, and “has become a model for communities nationwide committed to combating obesity and improving food access” (The Food Trust, 2004).

exercise, thereby creating a relationship between obesity and neighborhood violence. Let’s Move will incorporate programs to increase children’s physical activity opportunities by creating safe areas for exercise, particularly in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Let’s Move will include a multilingual awareness campaign and direct recommendations on improving the built environment and making outdoor play areas accessible in all communities. Other components of the fourth pillar include a revamping of the President’s Physical Fitness Challenge and an expansion of the Presidential Active Lifestyle Award.

Noting that some people legitimately believe that the government should not be telling people what to do, Sher emphasized that the position of the administration is that it should arm parents with the information to help them make better decisions. The recommendations are not designed to tell parents what to do.

Sher presented some of the recommendations that are being discussed. For example, recommendations on how to communicate nutrition information in simple, actionable ways will apply to the first pillar. Other recommendations related to the first pillar will focus on front-of-package food labels and the inclusion of calorie counts on menus and menu boards.

Recommendations made as part of the second pillar, on the nutritional quality of the food that is available in schools, will be paramount in efforts to reduce childhood obesity. The nutritional quality of school lunches and school breakfasts will be addressed, as will the nutritional quality of vending machine choices in schools. Other school-related factors include nutrition education, cafeteria design, and minimization of the stigma of receiving free or reduced-price meals at school. Foods served in juvenile justice facilities will also be considered.

Recommendations relevant to the third pillar, access to healthy and affordable food, will include a focus on the elimination of food deserts. Food pricing, particularly the relative pricing for healthy and unhealthy foods, will be considered. Product reformulation will also be discussed. For example, conversations with the food industry about reducing sodium levels can lead to voluntary commitments to lower sodium levels by 5 percent a year.

Recommendations for the fourth pillar, increasing physical activity, will include limitations to television watching and computer time for children. Many factors will be considered, including the number of hours of physical activity at school, school design, after-school activities, organized sports, and time simply to play. Access to safe playgrounds, parks, and both indoor and outdoor recreation opportunities will be the focus of attention. Spaces for indoor activities are particularly important in areas with extreme climates and areas where children are more likely to have asthma or other

health-related conditions. The role of the built environment—having walk-able, bikeable communities—is also important.

The recommendations will also include a focus on factors well outside parental control. For example, some research suggests that fetal or infant exposure to chemicals in the environment is related to obesity. Other cross-cutting recommendations will focus on prenatal care, breast-feeding, and the quality of food in child care settings. For instance, health care providers can also play a role in controlling obesity. The American Academy of Pediatrics is encouraging its members to measure the BMI of their patients. Pediatricians can also “prescribe” constructive recommendations for parents about healthy foods and exercise by writing them on a prescription pad.

Several other programs are related to the Obama administration’s efforts to reduce childhood obesity. The first program is the White House Task Force described earlier, which establishes an interagency task force on childhood obesity with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), USDA, the Department of Education, and the Office of the First Lady being the lead agencies. The first project of the task force is to create an action plan with specific recommendations.

Another program of the White House Task Force that Sher described is the Partnership for a Healthier America, funded by several philanthropic organizations. The partnership is a separate foundation that focuses on

• raising awareness of the health risks of obesity by independent, nonpartisan efforts,

• coordinating voluntary commitments by the private sector and the not-for-profit sector, and

• holding the federal government accountable by establishment of aggressive benchmarks.

Discussion

Anne Beal from the Aetna Foundation noted that although consensus around the recognition that obesity is a major health problem in the United States does seem to exist, there is considerably less agreement on how best to approach the problem of obesity. For example, some states are proposing a tax on sugary drinks and sodas. However, the federal government provides subsidies to farmers who grow some of the sugars used in these drinks. This is an issue that crosses policies at the local, state, and federal levels, and there is no easy way to resolve policy conflicts such as this one. Susan Sher noted that although this is a federal issue, there is no real consensus on resolving the federal farm subsidies. Rather, the First Lady’s Office is focused on those areas where consensus can be achieved.

REDUCING CHILDHOOD OBESITY: A STRATEGY TO ADDRESS HEALTH DISPARITIES

Mildred Thompson is director of the PolicyLink Center for Health and Place. Her work focuses on understanding community factors that affect health disparities and identifies practice and policy changes needed to improve individual, family, and community health.

Thompson began her comments by noting the shared focus of her work with First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move initiative described by Susan Sher. Addressing childhood obesity will require a multipronged approach, Thompson said, involving the federal government, private philanthropy, local government, and community action.

Thompson explained that because poor diet and physical inactivity have become the second leading actual cause of death in the United States (Mokdad et al., 2004), it is imperative to address the childhood obesity problem. In California, for example, 56 percent of adults are either obese or overweight, and 32 percent of adults in the United States are obese (Babey et al., 2009). The country now faces both moral and economic imperatives to make a real difference on this issue. The economic bottom line is that obesity costs families, governments, and the health care industry more than $6 billion per year in California alone.

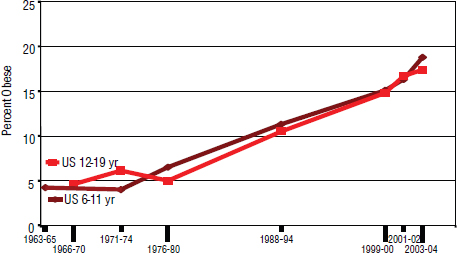

Looking at national trends in childhood obesity (Figure 5-1), Thompson pointed out the constant increase from the mid-1970s to 2004. Although rates for older children (ages 12 to 19 years) appear to have leveled off, the younger children (ages 6 to 11 years) present a great cause for concern. The distressing point is that these children suffer the effects of being obese in multiple ways, when obesity itself can be prevented in the first place.

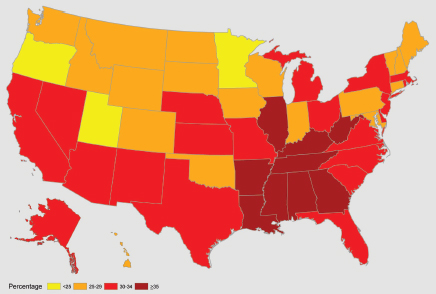

Figure 5-2 shows the disproportionate rates of childhood obesity across the United States, with the southern states having the highest obesity percentage rates. It is imperative that attention to childhood obesity be given to those regions that are hit the hardest by rising childhood obesity rates.

The consequences of childhood obesity are more than simply cosmetic. Rather, they are about the biology of obesity and how obesity affects the life course through a shortened life expectancy (Olshansky et al., 2005), the early onset of adult chronic diseases, and the associated medical costs of $147 billion (Finkelstein et al., 2009), Thompson said.

In response to these alarming trends in childhood obesity, a number of initiatives have been established to help alleviate the situation. For example, RWJF has invested $500 million in initiatives that will address childhood obesity. One key strategy has been the creation of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center to Prevent Childhood Obesity (www.rwjf.org/childhoodobesity). Box 5-1 presents the vision of that center. The center’s

FIGURE 5-1 National childhood obesity trends.

SOURCES: Ogden et al. (2002, 2006).

FIGURE 5-2 Percentage of children who are overweight or obese ages 10-17 years by state (2007).

SOURCE: Data retrieved from the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative 2007 National Surveys of Children’s Health Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health website (www.nschdata.org [accessed May 26, 2009]).

BOX 5-1

Vision of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center to

Prevent Childhood Obesity

• To be a strategic leader of the national movement to reverse childhood obesity

• Harness the impact of the RWJF programs and affiliated resources

• Advance a comprehensive policy agenda at the federal, state, and local levels

• The center’s policy strategy focuses on reversing childhood obesity and eliminating disparities by changing the environmental landscape in which this epidemic has developed

• Building community capacity to effect federal policy is the role of technical assistance for the center

SOURCE: Thompson (2010).

goal is to reverse the childhood obesity epidemic by 2015; funding is provided to support research on strategies to prevent obesity and encourage healthy eating.

Thompson noted that a nationwide movement is under way to address childhood obesity, with several other foundations being involved. For example, The Convergence Partnership is a national funder collaborative consisting of RWJF, The W.F. Kresge Foundation, Kaiser Permanente, the Nemours Foundation, The California Endowment, the Kellogg Foundation, and CDC, all of which are working to create healthy people in healthy places. This partnership, administered by PolicyLink in partnership with the Prevention Institute, seeks to support regional and national efforts to reduce obesity by focusing on creating healthy environments, both the food environment and the physical environment (www.convergencepartnership.org).

To make the kinds of complex changes needed, a focus only on individual behavior will not work, Thompson said; the environment has a significant impact as well. Where and how people live affect the trajectory of their lives. Therefore, to reduce obesity, the focus should be on changing the environments in which people live. By building community capacity, people can access the tools and resources to make better choices.

At present, RWJF is focused on creating a framework to shift the energy balance by (1) increasing children’s consumption of healthy food and beverages and decreasing the consumption of unhealthy foods, (2) addressing the need for increased physical activity, and (3) building awareness and support for efforts to reduce obesity. The factors of interest needed

to create this shift in the energy balance include the food environment, the built environment, and the educational setting.

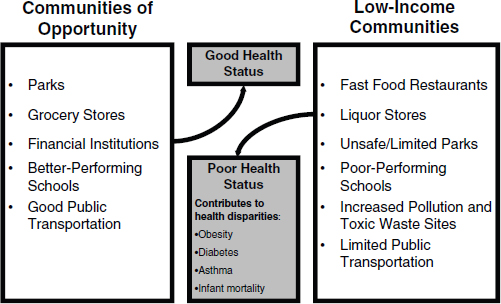

Figure 5-3 provides a model demonstrating that communities are not created equal. Comparison of the physical environments of high-income communities of opportunity with those of low-income communities of opportunity clearly shows the corresponding differences in health status between the two types of communities as a result of the different environments. This comparison shows why the focus should be on changing the environment, Thompson said.

Specifically, the educational environment is paramount as an influence on children’s health. Unfortunately, children from different communities have hierarchal opportunities based on where they live. If a neighborhood school does not offer advanced placement courses, for example, students at that school do not have the same kinds of educational opportunities available. This lack of opportunity, in turn, will affect their college performance. The educational environment should be changed to improve children’s health, Thompson said.

FIGURE 5-3 Communities of opportunity versus low-income communities.

SOURCE: Thompson (2010).

Policy Priorities

Thompson addressed the policy environment, an important component of the RWJF initiative, at the federal, state, and local levels. First, at the federal level, health care reform was a beginning and was more of a promise of achieving the right to health care for all Americans. At the state level, physical activity in school is critical; although many states have laws mandating physical activity, those laws are not always enforced.

A second federal initiative is the Child Nutrition Act. Thompson described the importance of the creation of food standards for schools and restaurants so that an informed consumer population can be created.

Third, public transportation in communities should be considered. Access to transportation provides increased opportunities for access to work, education, and health care. Access to transportation simply broadens one’s life choices, Thompson explained. Therefore, it is critical that federal transportation initiatives include public transportation as a component, and public health considerations should be a part of the transportation reauthorization conversation.

Fourth, food marketing is another issue of concern. Because children spend so much of their free time on “screen time” (television, cell phones, videogames, computers, other digital equipment), it is easy for food marketers such as fast food chains to bombard them with messages about food that are incorrect or encourage the consumption of unhealthy foods. Thompson suggested that one avenue to address this problem is to work with the Federal Trade Commission.

Additionally, access to fresh, healthy foods is critical to battling obesity. As mentioned earlier by Sher, one federal effort to increase access to fruits and vegetables is based on the Fresh Food Financing Initiative, a successful statewide model in Pennsylvania. The Obama administration’s Healthy Food Financing Initiative is an effort to replicate and scale up that successful model to a national level.

Furthermore, the United States is rapidly becoming a more diverse nation, with changing demographic data indicating rapid growth in the Latino population in particular. Faced with increasingly diverse communities, care should be taken to meet the broad range of needs that will help new population groups become—and remain—healthier. As David Williams described earlier (see Chapter 2), immigrants entering the United States tend to be healthier than those immigrants who have lived here for a period of time. Therefore, a crucial task is to focus on addressing the social determinants of health through strategies such as the RWJF Childhood Obesity program so that more communities of opportunity can be created. Talking about food deserts is not enough. Rather, a variety of strategies should be implemented, including provision of access to supermarkets, increasing

the numbers of farmers markets in urban communities, and working with convenience store owners to change their product placements and provide more refrigeration for fruits and vegetables. Rather than telling people what they are doing wrong, Thompson said, “assist them with making better choices.”

Lastly, the connection to the built environment also needs to be better understood. Land use policies and zoning laws should also be subject to policy changes. Initiatives are under way in some cities (for example, Los Angeles) to place moratoriums on the number of new fast food restaurants in communities that are already filled with fast food choices.

THE CALIFORNIA ENDOWMENT’S BUILDING HEALTHY COMMUNITIES INITIATIVE

Mary Lou Fulton is program Officer for The California Endowment’s (TCE’s) Building Healthy Communities Initiative. Acknowledging the comments of earlier speakers in highlighting the strategies for building healthy communities, Fulton stated that the Building Healthy Communities Initiative is moving forward with these innovative strategies and trying them out at the community level.

TCE is California’s largest foundation focused on health. Its mission is specifically focused on improving the health of underserved populations in the state. Previously, grant-making efforts focused on three policy areas: access to health care, cultural competence and workforce diversity, and community health and disparities. Although important progress was made, Fulton said, the question became whether a more focused strategy could have a greater impact.

Therefore, a new strategy combines policy and place to achieve greater progress. Place, Fulton emphasized, determines the opportunities available for good health. In other words, an individual’s zip code—where that person lives—determines how long and how well that person lives. The strategy also focuses on the nexus of community, health, and poverty. The conversation really needs to be about preventing disease in the first place, Fulton said, and all of the factors that exist in the surrounding communities are essential to making that happen.

The Building Healthy Communities Initiative is a 10-year strategy investing in 14 communities in California. As California has an extremely diverse population, the selected communities are diverse themselves. The strategy is focused on changes to policies and systems rather than provision of funding for services. In this way, local neighborhoods have the opportunities to define those policies and systems that need to change to create healthier communities. The strategy is about giving local communities the power to make changes in their community, Fulton said, and the hope is

that the innovations coming from the grassroots level will provide models for statewide and even nationwide systems change.

The strategy is structured around 10 outcomes and 4 big results (Box 5-2). The outcome areas range from children’s health, the built environment, and land use policies to economic development, schools, and youth development. In particular, a special focus is on boys and young men of color in California and targeting of funding specifically for the challenges that they face. The four big results are the indicators of achievement for the strategy, including a “health home” for all children, a reverse of the childhood obesity epidemic, increases in school attendance, and reductions in youth violence. The project also has a strong focus on community organizing and youth development. Other institutions in the public and private sectors will ideally become involved and participate in the process of making change happen.

BOX 5-2

The California Endowment’s

Building Healthy Communities Initiative

Ten Outcomes and Four Big Results

Ten outcomes

• All children have health coverage

• Families have access to a “health home” that supports healthy behaviors

• Health and family-focused human services shift resources toward prevention

• Residents live in communities with health-promoting land use, transportation, and community

• Children and families are safe from violence in their homes and neighborhoods

• Communities support healthy youth development

• Neighborhood and school environments support improved health and healthy behaviors

• Community health improvements are linked to economic development

• Health gaps for boys and young men of color are narrowed

• California has a shared vision of community health

Four big results (indicators of achievement)

• Provide a “health home” for all children

• Reverse the childhood obesity epidemic

• Increase school attendance

• Reduce youth violence

SOURCE: http://calendow.org/healthycommunities and http://MidCityCAN.org.

Mid-City Community Advocacy Network

Diana Ross is the director of the Mid-City Community Advocacy Network (Mid-City CAN) in City Heights, San Diego, California. City Heights is home to 1 of the 14 Building Healthy Communities sites funded by TCE. It is located about 16 miles north of the United States–Mexico border crossing and is east of the downtown coastline of San Diego. City Heights is also bordered by four of the five major freeway arteries in the San Diego metropolitan area.

Ross noted that the City Heights of today can be traced back to the policies of the 1960s, when deliberate policy decisions were made to create density in the City Heights community as part of an economic development strategy. Inevitably, said Ross, in the 1970s this led to “white flight”; absentee landlords; and decreases in the quality of life, health, and well-being of City Heights residents. This serves as a clear case of how decisions related to policies and systems can disproportionately affect particular communities, which in turn can create pockets of disparities.

Ross described City Heights as the most diverse community in San Diego, with a population of about 90,000 people. The local school district has identified 30 different languages and 80 dialects spoken in students’ homes. Unemployment rates are more than 20 percent, roughly double the average rate for both the county and the United States. Average income levels for a family of four are at about the federal poverty line. Moreover, City Heights also has high rates of school dropout, obesity, violent crime, and sexual assault.

Moreover, San Diego has very high hunger rates, as well as some of the lowest rates of participation in the federal food stamp program. Ironically, said Ross, efforts to reestablish a community garden required significant grassroots organizing and advocacy. Access to the garden can help families bolster their nutrition, help reduce childhood obesity, and improve the overall health of the community.

The Building Healthy Communities Initiative began in City Heights, Ross described, with Mid-City CAN convening a public community forum that was attended by about 300 residents and nonprofits. Next, the Mid-City CAN Coordinating Council called for residents to submit their names for the Resident Selection Committee. Three members were randomly selected from a total of 89 applicants in a public ceremony held on the steps of the public library. In this way, the process was completely transparent and equitable from the start.

The Resident Selection Committee then developed a short request for proposals for the creation of an Oversight Committee of 13 nonprofit organizations (49 nonprofits had applied). The Oversight Committee was in charge of designing the planning process for the Building Healthy Communities

Initiative efforts. These efforts included house meetings with house meeting leaders and momentum teams (working groups).

The purpose of the house meetings was threefold: community organizing at the grassroots level, education about systems and policy change, and data collection. House meeting leaders participated in an intensive 3-day training process. A total of 105 house meetings conducted in 13 different languages were held, and more than 1,550 residents of City Heights participated in those meetings.

The next step was the creation of six momentum teams that served as working groups. These teams worked with more than 1,300 residents. The work of the momentum teams is clustered around TCE’s 4 big results and 10 outcomes (Box 5-2). The most important issue raised during the house meetings was how to make concepts like “policies” and “systems change” meaningful to people in the community. Additionally, residents remarked that they were tired of people asking them questions, given that a number of community plans were already working in the region. There was a strong sense that “planning fatigue” was occurring.

The critical distinction between the Building Healthy Communities Initiative process and other community plans is that this process is a community capacity-building process and an education process. Most nonprofits, for example, use a service delivery model. With the Building Health Communities Initiative process, the focus is on advocating for policy and systems change.

TCE required the Mid-City CAN to have the community prioritize its own 10 outcomes. The priority-setting process was based on data collected by house meeting leaders during the house meetings. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected, processed, and compiled into a report that was fed back to the six momentum teams. Two lenses were used during the prioritization process: the lens of data and the lens of the importance of early wins. City Heights residents believed that it was critical that any strategies arising from the priority setting in particular or from the Building Healthy Communities Initiative in general should directly affect the City Heights community in the form of real, tangible changes.

Ross offered three final conclusions. First, the investment made in grassroots organizing in the City Heights community paid off by community buy-in, an increase in community pride, and a strengthening of civic participation. Second, a critical element of this process was learning to translate the abstract concepts of “policy” and “systems change” into language and ideas that are meaningful to the community. Community capacity building along the way was also essential. This, too, helped to build community buy-in. Finally, careful data collection for the purposes

of prioritization of outcomes helped to cultivate buy-in and kept any one stakeholder group from having undue influence on the process and outcomes. This also helped establish baselines for future evaluation efforts.

The discussion opened with a question about sustainability. Patricia Baker of the Connecticut Health Foundation wondered how it is possible to translate what is learned from a successful program into longer-lasting policy change. Mildred Thompson responded with an example of a successful scaled-up policy: California was the first state to ban soft drinks in schools. This ban was implemented in steps, however, rather than all at once. The initial focus was on elementary schools, and the case was made—on the basis of the scientific evidence—that sugar-sweetened beverages are linked to childhood obesity. Then, later, the ban was taken to the high school level, with the eventual result being that all schools in California became soda free. Other states followed California’s model, providing an example of how a promising practice at the local level can be scaled up.

A second example, explained Thompson, is the Fresh Food Financing Initiative that began in Philadelphia. This is a public-private partnership effort to bring large-scale grocery stores (as opposed to corner markets) into food deserts, which are urban areas without access to fresh, healthy, affordable fruits and vegetables. This initiative has now expanded to Detroit, Michigan, and New York City as well, with the Obama administration trying to take it to the national level with the Healthy Food Financing Initiative.

Mary Lou Fulton of TCE explained that it is critical to focus funding on both place and policy. Although community-level investments are crucial, funding for advocacy efforts at the regional, statewide, and national levels should also be provided. Both are necessary, she said, to make large-scale changes.

Lisa Egbuonu-Davis of the Gateway Institute for Pre-College Education asked about the inclusion of community businesses and entrepreneurs in the process described by Fulton. She stated that inclusion of these groups among the stakeholders could be important to the long-term sustainability of the systems changes that TCE is expecting. Ross explained that local businesses and entrepreneurs were a part of the partnerships created with their program in City Heights. All of the work of the Mid-City CAN was community driven, she said.

Babey, S. H., M. Jones, H. Yu, and H. Goldstein. 2009. Bubbling over: Soda consumption and its link to obesity in California. Health Policy Research Brief. September. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2007. National Surveys of Children’s Health. www.nschdata.org (accessed May 26, 2009).

Finkelstein, E. A., J. G. Trogdon, J. W. Cohen, and W. Dietz. 2009. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: Payer- and service-specific estimates. Health Affairs 5:w822-w831.

The Food Trust. 2004. Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative: Encouraging the Development of Food Retail in Underserved Pennsylvania Communities. www.thefoodtrust.org (accessed May 26, 2009).

Koebnick, C., N. Smith, K. J. Coleman, D. Getahun, K. Reynolds, V. P. Quinn, A. H. Porter, J. K. Der-Sarkissian, and S. J. Jacobsen. 2010. Prevalence of extreme obesity in a multiethnic cohort of children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatrics 157(1):26-31.e22.

Mokdad, A. H., J. S. Marks, D. F. Stroup, and J. L. Gerberding. 2004. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Journal of the American Medical Association 291(10):1238-1245.

Nord, M., M. Andrews, and S. Carlson. 2009. Household food security in the United States, 2008. Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Ogden, C. L., K. M. Flegal, M. D. Carroll, and C. L. Johnson. 2002. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999-2000. Journal of the American Medical Association 288(14):1728-1732.

Ogden, C. L., M. D. Carroll, L. R. Curtin, M. A. McDowell, C. J. Tabak, K. M. Flegal. 2006. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. Journal of the American Medical Association 295(13):1549-1555.

Olshansky, S. J., D. J. Passaro, R. C. Hershow, J. Layden, B. A. Carnes, J. Brody, L. Hayflick, R. N. Butler, D. B. Allison, and D. S. Ludwig. 2005. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. New England Journal of Medicine 352:1138-1145.

Thompson, M. 2010. Reducing Childhood Obesity—A Strategy to Address Health Disparities. Presentation to the IOM Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity and the Elimination of Health Disparities, April 2010, Washington, DC.

United Health Foundation, American Public Health Association, and Partnership for Prevention. 2009. America’s Health Rankings: A Call for Innovative Actions to Individuals and Their Communities. St. Paul, MN: United Health Foundation.

The White House, Office of the First Lady. 2010. First Lady Michelle Obama Launches Let’s Move: America’s Move to Raise a Healthier Generation of Kids. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-Office/first-lady-michelle-obama-launches-lets-move-americas-move-raise-a-healthier-genera (accessed May 3, 2012).