Appendix A

The Other Side of the Coin:

Attributes of a Health Literate

Health Care Organization

Dean Schillinger, M.D.1

Debra Keller, M.D., M.P.H.2

INTRODUCTION

Background

Health literacy has been defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (IOM, 2004). Health literacy encompasses a range of skills that individuals need to function effectively in a complex and demanding health care environment. These include literacy skills (reading and writing), oral skills (listening and speaking), numerical calculation and quantitative interpretation skills (numeracy), and, increasingly, Internet navigation skills. Nearly 90 million adults in the United States have limited health literacy. While limited health literacy affects individuals across the entire spectrum of socio-demographic characteristics, it disproportionally affects more vulnerable populations, including the elderly, disabled individuals, people with lower socioeconomic status, ethnic minorities, those with limited English proficiency, and people with limited education (National Center for Education Statistics, 2006). Some of these subgroups are precisely the

![]()

1 Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Communications Program, Center for Vulnerable Populations, Department of Medicine at San Francisco General Hospital, University of California, San Francisco.

2 Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine at San Francisco General Hospital, University of California, San Francisco.

populations that have the potential to benefit the most from the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), especially if health literacy barriers are attended to (Martin and Parker, 2011).

Compared to individuals with adequate health literacy, individuals with limited health literacy have been shown to have greater difficulty in communicating with clinicians (Schillinger et al., 2004), to be less likely to participate in shared decision making (Sarkar et al., 2011), and to face greater barriers in managing chronic illnesses (Cavanaugh et al., 2008; Williams et al., 1998). Furthermore, limited health literacy appears to be a barrier to access to care, receipt of preventive and self-management support services, and safe medication management (Sarkar et al., 2008, 2011; Sudore et al., 2006). Compared to populations with adequate health literacy, populations with limited health literacy have been shown to have worse self-reported health (Baker et al., 1997), higher rates of many chronic conditions (Sudore et al., 2006), worse quality of life, and intermediate markers of health in some chronic conditions (Schillinger et al., 2002); to experience serious medication errors (Schillinger et al., 2005); and to have increased risk of hospitalization (Baker et al., 2002) and mortality (Sudore et al., 2006). Compared to patients with adequate health literacy, patients with limited health literacy exhibit patterns of utilization of care reflecting a greater degree of unmet needs, such as excess emergency room visits and hospitalizations, even when comorbid conditions and health insurance status are held constant (Hardie et al., 2011). It has been estimated that limited health literacy leads to excess health expenditures of greater than $100 billion annually (Vernon et al., 2007). Improving limited health literacy has been identified as a key strategy to improving the safety, quality, and value of health care (Joint Commission, 2007; National Quality Forum, 2009).

Rationale for This Paper

The vast majority of research on health literacy has focused on characterizing patients’ deficits, on how best to measure a patient’s health literacy, and on clarifying relationships between a patient’s limited health literacy and health outcomes. In addition, most health literacy intervention research has studied how to intervene with patients who have limited health literacy.

There is a growing appreciation, however, that health literacy is a dynamic state that represents the balance (or imbalance) between (a) an individual’s capacities to comprehend and apply health related knowledge to health-related decisions and to acquire health-related skills, and (b) the health literacy–related demands and attributes of the health care system. There is a clear need to develop, in parallel, a set of strategies that

health care organizations can develop and implement to enable patients and families to access and benefit as much as possible from the range of health care services and to successfully interact with the range of health care entities involved in contemporary health care. The need to address system-level factors that place undue health literacy demands on all patients utilizing the health care system has been emphasized by a variety of government entities, public policy organizations, trade organizations, and research funders, including the Surgeon General’s Office (U.S. Surgeon General, 2006), the American Medical Association Foundation (AMA, 2007a, 2007b), the Joint Commission (Joint Commission, 2007), America’s Health Insurance Plans (America’s Health Insurance Plans, n.d.), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (HHS, 2010), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Institutes of Health.

There is perhaps no more critical time than now to shift focus from the health literacy skills of patients to the health literacy–promoting attributes of health care organizations. Enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)3 provides opportunities to improve the experience of care and the health outcomes for limited–health literacy populations through insurance reform, Medicaid expansion, and the establishment of health insurance exchanges. Maximizing this opportunity will require that health care organizations attend to the communication needs of limited–health literacy populations. The success of a number of ACA-related redesign initiatives, such as patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) and accountable care organizations (ACOs) will depend on the stewardship of health care organizations committed to prioritizing the needs of limited–health literacy populations. The expected benefits of insurance expansion will depend on individuals’ ability to navigate the complexities of the insurance exchange; without special assistance and institutional commitments, many individuals may not fully benefit from the new system (Martin and Parker, 2011; Sommers and Epstein, 2010). In addition, through the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act) legislation created to stimulate the adoption of electronic health records and supportive technology, health care providers are being offered financial incentives for demonstrating meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs), including sharing detailed health information with patients electronically. Whether the benefits of health information technology (IT) will accrue for patients with the greatest needs for communication support will depend on the uptake of health IT among populations with limited health literacy. This, in turn,

![]()

3 111th Congress, 2nd session. March 23, 2010. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. In Public Law 148.

will depend on the extent of investments made to tailor products to the needs of these populations and the health systems that disproportionately care for them.

This paper attempts to identify and describe a set of goals or attributes that diverse health care organizations can aspire to so as to mitigate the negative consequences of limited health literacy and improve access to and the quality, safety, and value of health care services. We describe organizations that have committed to improving and reengineering themselves as “health literate health care organizations” so as to better accommodate the communication needs of populations with limited health literacy, which reinforces the notion that the health care sector shares significant responsibility in promoting health literacy (IOM, 2004).

A foundational principle of health literate health care organizations is that they make clear and effective patient communication a priority across all levels of the organization and across all communication channels. These organizations recognize that health literacy skills are highly variable among the populations they serve and that many of their systems are poorly designed to take into account limited health literacy skills. They also recognize that literacy, language, and culture are intertwined and, as such, their health literacy efforts complement and augment effort to improve their organizations’ linguistic and cultural competencies and capacities. These organizations also recognize that clinician–patient miscommunication is very common, and they apply a “universal precautions” approach to communication, whereby communication is simplified to the greatest extent possible and comprehension is not assumed to be achieved unless it can be demonstrated. “Universal precautions” represents a public health approach to communication that attempts to ensure effective basic communication for the largest proportion of the population at the lowest cost. Health literate health care organizations, however, also pay particular attention to ensuring that patient skill-building efforts reach the populations most in need by making special investments, and they recognize that special system redesign efforts may be needed to further reduce health literacy demands in order to better match the health literacy demands of the health care system with the skills of subpopulations so as to mitigate the untoward effect of individuals’ limited health literacy skills on their health. A health literate health care organization that openly acknowledges the centrality of clear and interactive communication and invests in optimizing communication for more vulnerable populations can realize benefits for patient access, satisfaction, quality, and safety; can reduce unnecessary patient suffering and costs; can enhance health care provider well-being; and can improve its risk management profile. Finally, a health literate health care organization recognizes the centrality

of interprofessional communication as an important means to reduce the informational demands on patients, especially during transitions in care.

The most proximate goals of these organizational investments are to maximize the extent of patients’ and families’ capacities to (a) comprehend and engage in recommended preventive health behaviors and receive preventive health care services if desired; (b) recognize changes in health states that require attention and access health care services accordingly; (c) develop meaningful, ongoing relationships with health care providers based on open communication and trust; (d) obtain timely and accurate diagnoses for both acute and chronic health conditions; (e) comprehend the meaning of their illness, their options for treatment, and the anticipated health outcomes; (f) build and refine the skills needed to safely and effectively manage their conditions at home and to communicate with the health care team when illness trajectory changes; (g) report their communication needs or comprehension gaps; (h) make informed health care decisions that reflect their values and wishes; and (i) effectively navigate transitions in care. In addition, these investments can enable people to make more appropriate health care coverage choices based on their own health needs or those of their families, to better comprehend the range of benefits and services available to them and how to access them, and to be more aware of the financial implications of their health care choices so as to improve decision making.

The list of attributes and goals for health literate health care organizations included in this paper is by no means exhaustive, and it simply represents our attempt to synthesize a body of knowledge and practice supported to the greatest extent possible by the state of the science in the young field of health literacy. The attributes and goals that we outline are most well-developed for and most clearly applicable to organizations that provide direct care to patients. However, a majority are also relevant to the broader range of organizations and institutions that comprise the modern health care system, such as health insurers and health plans, pharmacies, pharmacy benefits managers, disease management companies, and vendors of health IT and patient education products. We see this paper less as a definitive response to the challenge of defining a “health literate health care organization” and more as an attempt to advance a vision of how organizations should evolve to be more responsive to the needs of populations with limited health literacy in tangible ways, thereby improving care for all.

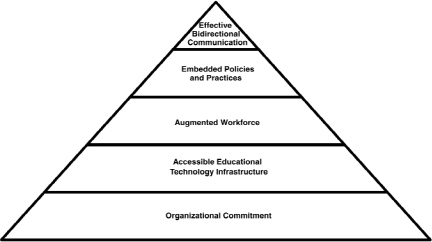

FIGURE A-1 Features of a health literate health care organization.

ATTRIBUTES AND GOALS FOR HEALTH LITERATE HEALTH CARE ORGANIZATIONS

When making communication an organizational priority, health literate health care organizations embrace a package of central principles and practices with respect to organizational structures, processes, personnel, and technologies for enabling patient care and population management so as to mitigate the untoward effect of individuals’ limited health literacy skills on their health and health care costs (Figure A-1).

1. Establish Promoting Health Literacy as an Organizational Responsibility

Organizational leaders should establish a culture of clear communication. Leadership should raise organization-wide awareness about the importance of health literacy and clear communications across all facets of the health care system and should participate in local, state, and national efforts to improve organizational responses to limited health literacy. Organizational leaders should make clear statements about the responsibility of all sectors of their health care system to advance patients’ and families’ capacities to learn about their illness, carry out self-care, effectively communicate, and make informed decisions. Leaders should create an organizational expectation that patients, families, and caregivers are well supported in understanding and managing their health and that

suboptimal communication outcomes due to lack of effort, expertise, or infrastructure are viewed as a systems failures and are addressed through systems redesign. Health literate health care organizations may choose to employ a health literacy officer or high-level health literacy task force to ensure that health literacy is deeply, explicitly, and continually integrated into quality-improvement activities, cultural and linguistic competence efforts, patient safety initiatives, and strategic planning. Ongoing organizational assessments should be carried out to reflect organizational performance and progress in promoting health literacy. Promoting health literacy should be considered when planning organizational operations, job descriptions, evaluation metrics, and budgets. Systems can be put in place to ensure that members of the health care team have adequate time and incentives to learn and implement basic health literacy tools as well as to access more sophisticated resources when necessary. Resources can be earmarked for patient education experts and community advisory group members who can both train frontline providers and develop and administer specialized curricula to patients with demonstrated need.

2. Develop a Culture of Active Inquiry, Partner in Innovation, and Invest in Rigorous Evaluations of Operations Improvements

While the untoward health and economic outcomes associated with limited health literacy are now established, the value of existing intervention research to health literacy programming at the operations level is hampered by the relative infancy of the field and inconsistent results. A recent systematic review of interventions designed to mitigate the effects of limited literacy found consistent results for only a select number of discrete design features aimed at improving participant comprehension (presenting essential information by itself or first, presenting information so that the high number is better, presenting numerical information in tables rather than text, adding icon arrays to numerical information, and adding video to verbal narrative) (Sheridan et al., 2011). In addition, some studies found that intensive mixed-strategy interventions focusing on self- and disease-management reduced emergency and hospital utilization as well as disease severity. The common features of mixed-strategy interventions that changed health outcomes included having a basis in theory, carrying out a pilot test, being high intensity, having an emphasis on skill building, and being delivered by a health professional. Finally, the relative paucity of real-world implementation research involving representative populations in nonacademic health care settings has further limited the value of prior research efforts for informing health literacy programming at an organizational level. Rather than waiting for others to identify solutions, health literate health care organizations develop

mutually beneficial partnerships with health literacy researchers spanning a range of disciplines to help develop, identify, implement, and evaluate health literacy interventions whose results will have an immediate relevance to organizational processes (Allen et al., 2011).

3. Measure and Assess the Health Literacy Environment and Communication Climate

A health literate health care organization establishes ongoing mechanisms and metrics to measure the success of its system in achieving the health literacy attributes described above, to evaluate special health literacy programs, and to identify areas for further improvement. Such organizations perform institutional health literacy reviews focused on the health literacy environment and the variety of communication and support systems in place. Templates for such reviews have been made available by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for both health practices (DeWalt et al., 2010) and pharmacies (Jacobson et al., 2007) and can be adjusted to apply to any health care organization. An organizations can undertake a 360-degree assessment of its communication climate and culture. For example, there is evidence that a better organizational communication climate, as measured by the Communication Climate Assessment Tool, is associated with better quality of care (Wynia et al., 2010). In addition, if investments have been made for the educational support infrastructure as described above, organizations can monitor patient understanding of their medical conditions both on individual and population levels. Organizations can also track provider implementation of best practices in communication and can institute additional educational initiatives and incentives to encourage adoption of these practices. Health plans, health insurance organizations, and Medicare prescription benefits plans will need to develop assessment tools similar to those of other customer service industries but that include the attributes described above. An example of a self-assessment tool recently developed for health insurers is the Health Plan Organizational Assessment of Health Literacy Activities developed by Gazmararian and colleagues for America’s Health Insurance Plans (America’s Health Insurance Plans, n.d.; Gazmararian et al., 2010). This tool assesses health plans in six areas: printed member information, Web navigation, member services/verbal communication, forms, nurse call lines, and member case/disease management.

4. Commission and Actively Engage a Health literacy Advisory Group That Represents the Target Populations

Too often end users with limited literacy skills are consulted only for the evaluation component of an intervention in order to assess established curricula or else are never consulted at all. As a concrete example of community engagement, health literate organizations can involve health literacy advisory groups in the development and implementation of clear communication strategies and in the formulation of organizational policies around health literacy and clear communication. The advisory group can also participate in needs assessments, review educational materials, test new health IT applications, and be part of the evaluation team assessing the successes of an organization’s health literacy programming. Health literate health organizations involve members of lower-literacy populations, adult educators, and experts in health literacy in the development, implementation, and assessment of communication strategies and in ensuring that user-centered design principles are adhered to and that members of the target community are key collaborators in intervention design and implementation. Management teams can commission an advisory group of community literacy experts (including educators and limited-literacy populations) for this purpose. For example, the Department of Health and Human Service’s National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy highlights the collaborative efforts of the Iowa Health System and the New Readers of Iowa as an exemplary model for partnering with community-based organizations as a means of enabling community involvement, guidance, and oversight regarding health literacy activities (HHS, 2010). Some advisory groups evolve into ongoing patient learning resource centers or serve as key connectors to community adult literacy programs.

5. Provide the Infrastructure to Avail Frontline Providers, Patients and Families with a Package of Appropriate, High-Quality Educational Supports and Resources

While frontline clinicians can develop the skills and attitudes to be clear and effective communicators and to assess patients’ level of comprehension and preparedness, they cannot independently provide the depth, quality, and complexity of communication needed for every patient and every situation, nor can they consistently and reliably carry out the iterative assessments and educational efforts required to maximize patient understanding and skill acquisition over time. Health literate health care organizations recognize that promoting patient comprehension and building patient skills requires high-quality human, technical, and pedagogical resources that are easily accessible across the organization. As such,

they provide clinicians and patients access to a functional infrastructure and a package of high-quality educational supports, including written materials, video material, online material, and in-person and group-level education that adheres to clear communication and user-centered design principles. While adjunctive written health information serves as a critical method of reinforcing health knowledge and behaviors introduced during in-person interactions, it can only serve as such if its language, content, and design elements facilitate comprehension. Health literate health care organizations can also establish a formal process of involving the members of the low-literacy community via a health literacy advisory board in planning, developing, and testing written health information to ensure appropriateness. Multiple tools are available to assist health educators and administrators tasked with developing health-related written materials (NCI, 1994). Key components include attention to the use of simple, everyday words; short sentences; appropriate graphics; and well-designed layouts. There should also be a focus on the content of the health material, with an emphasis on “chunking” information into discrete, manageable, content and focusing on actionable health items rather than general information.

Health literate health care organizations make a commitment to providing patients and families with communication and educational support beyond the face-to-face clinician visit to the greatest extent possible. This support can involve visit preparation, post-visit reinforcement, self-management support, decision support, and educational reinforcement during transitions in care. This requires a health literate health care organization to develop a functional educational infrastructure to support providers, patients, and caregivers. Ideally, many educational materials, decision aids, and supports are linked to the organization’s electronic health record. While there are many institutions and organizations that produce such material, to our knowledge there is no single clearinghouse that provides an all-encompassing compendium of health literacy–appropriate material. There are, however, publicly available websites for patient education that provide certain materials that may be more comprehensible to the average U.S. patient (e.g., Medline-Plus has an easy-to-read icon for material written at the fifth- through eighth-grade levels and “tutorials” written at the fifth- and sixth-grade levels, and it also has an extensive library of materials in Spanish) (NLM, 2012), and some vendors of patient education materials promote the readability of their products. Self-management support programs have been found to be effective for populations with chronic disease and limited health literacy (Baker et al., 2011a; Rothman et al., 2004; Schillinger et al., 2009). Decision aids that use simplified text and complementary video can improve decisional intent in dementia care planning in populations with limited

health literacy (Volandes et al., 2007, 2010), and decisional aids developed through participatory methods can improve decision making in breast cancer care, reducing decisional conflict to a greater degree among those with the least knowledge (Belkora et al., 2011a, 2011b). Finally, the use of virtual patient advocates (embodied conversational agents) as health educators as a complement to in-person discharge education has been shown to reduce rehospitalization, with similar benefits across health literacy levels (Bickmore et al., 2009).

Health literate health care organizations have an instrumental role in influencing the marketplace of patient communication products by demanding rigorous testing with and adaptation for populations with limited health literacy and in supporting the development of national certification standards for print and digital material that is accessible to these populations.

6. Leverage Accessible Health Information Technology (IT) to Embed Health Literacy Practices and Support Providers and Patients

Because effective communication can be time-consuming and because of the high variability in both provider communication skills and patient literacy and learning styles, health IT holds significant promise for enabling patients to provide information and for providing patients with assistance in learning about their conditions and treatments, making decisions, and managing their conditions at home. In addition to enabling forms of communication beyond the written word (visual aids, spoken word), health IT can provide both standardized and tailored information based on patient information or needs and can carry out iterative education to ensure comprehension and mastery, thereby embedding an established health literacy practice. If developed and pretested with populations with limited health literacy, such health IT applications can be highly effective and provide opportunities to deliver education and elicit communication across multiple modalities. Examples include automated telephony for diabetes self-management in the home (Schillinger et al., 2009) and embodied conversational agents for discharge instructions at the bedside (Bickmore et al., 2009). These types of applications can be employed across a range of patient informational and communication needs and strategies, such as pre-visit preparation, after-care summaries, or proactive outreach for health care maintenance, appointment keeping, or medication adherence, among others. AHRQ is currently supporting an effort to develop a set of standards to determine the attributes of electronic health communication resources that make them appropriate for populations with limited health literacy. As described above, health literate health care organizations not only show a willingness to employ such

innovations, but they also participate in the innovation process by adapting them to the needs of patients with limited health literacy or requiring that vendors of such applications have demonstrated their effectiveness with these populations before purchasing them.

7. Provide Patient Training and Assistance Around Personal Health Records and Health IT Tools

eHealth literacy refers to the “ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise information from electronic sources and apply this knowledge to addressing or solving a health problem” (Norman and Skinner, 2006). Patients with limited health literacy often have low eHealth literacy. One specific form of interactive health IT, personal electronic health records (pEHRs), gives patients the ability to store and access personal health information, interact with their providers, and receive electronic educational resources. While these technological advances can improve access to health information and advance self-management in some cases, their introduction may widen communication disparities between those patients with adequate health literacy skills and those without. A recent study found that having limited literacy skills was independently associated with significantly lower rates of using a personal health record to make appointments, review medication regimens, refill medications, check laboratory results, or e-mail one’s provider, even among those with Internet access (Sarkar et al., 2010a).

Health literate health care organizations take steps to ensure that patients with low health and eHealth literacy are able to benefit from technological advances. Health literate health care organizations advocate that IT firms developing pEHR implement best practices in health IT, including simple home page design with minimal text per screen, use of HTML for websites, a consistent and simple navigation approach, simplified search tools, a minimized need for scrolling, the availability of printer-friendly options, and easy-to-find contact information (Eichner and Dullabh, 2007). Health literate health care organizations should solicit input from the target community on the development and selection of pEHR systems. A detailed checklist has been developed by the National Resource Center for Health IT and AHRQ (Eichner and Dullabh, 2007); health literate health care organizations adhere to these recommendations when developing their own applications and when purchasing products from vendors. Health literate health care organizations implement educational initiatives so that end users can be oriented, assisted, trained, and motivated in pEHR use to the greatest extent possible. Finally, because the diffusion of digital innovations will be slower among populations with limited health literacy, health literate health care organizations do not sup-

plant human connection with digital options; information and education available on pEHR should also be accessible through interpersonal means.

8. Foster an Augmented and Prepared Workforce to Promote Health Literacy

The current structure of the U.S. health care system places emphasis of communication and education on the physician provider. Patients with limited health literacy report suboptimal verbal communication with their physicians (HRSA, n.d.; Schillinger et al., 2004). As care delivery shifts toward the patient-centered medical home model and accountable care organizations, health literate health care organizations should diversify their provider workforce and expand job descriptions in line with the variety of educational roles that nonphysician members of the health care team will serve in patient-centered health homes. Priority should be placed on hiring and integrating health educators, health coaches, social workers, patient navigators, nurses, medical assistants, and even peers into health management and health education roles. Health literate health care organizations should also ensure that members of the health care team reflect the socio-demographic profiles of the patient populations served as another means to improve trust and communication. Health literate organizations should also develop “expert educators” with cross-cutting educational skills who can teach others how to teach, can teach about specific medical conditions, can help evaluate the educational and communication needs of patients to refine or identify appropriate new curricula, and can serve as organizational contacts to identify electronic educational resources. These approaches to redesigning the workforce, however logical, will require evaluation to demonstrate a return on investment, as their effectiveness in reducing health literacy–related disparities has not been well studied (Sheridan et al., 2011).

A health literate health care organization provides health literacy and health communication training for all members of the integrated health team: receptionists, team members tasked with helping patients enroll in insurance benefits or receive social services, case managers, and all medical providers. The goal of this training is to provide all members of the team with basic competencies in clear communication and the ability to recognize when patients have communication barriers for which clear communication is insufficient and thus need more intensive communication support. Through widespread training, health literate organizations can establish a culture in which all members of the health care team work with the unified goal of promoting open communication with patients. Health care team members specifically tasked with health education roles should receive more detailed training in educational techniques that help

patients achieve mastery over health care material. A number of comprehensive and well designed health literacy educational modules are available online (AMA, 2007b; DeWalt et al., 2010; HRSA, n.d.; New York New Jersey Public Health Training Center, 2011).

Health literacy experts have identified a number of best practices in communication that all members of the health care team can employ when interacting with patients. These include the following:

• Assessing patient comprehension of pre-specified knowledge domains and ability to demonstrate specific skills

• Avoiding medical jargon and using plain, everyday (“living room”) language in conversation

• Limiting the amount of information introduced in each conversation

• Prioritizing learning goals to two to three concepts per visit

• Actively eliciting patient’s symptoms and concerns

• Using the “teach back,” “teach to goal,” and “show me” methods (Schillinger et al., 2003) to ensure patient comprehension and skills. This has been identified as a top safety practice by the National Quality Forum (National Quality Forum, 2005, 2010).

• Encouraging the asking of questions

• Focusing on information that is actionable

9. Distribute Resources to Better Meet the Needs of the Populations Served

The inverse care hypothesis, a concept that has been applied to explain health care disparities, states that the availability and quality of health care tends to vary inversely with the needs of the population (Schillinger, 2007). Health literate health care organizations, however, recognize that the distribution of the health literacy workforce across the organization should be commensurate with the local needs of the populations served. As such, health literate health care organizations reallocate existing resources or allocate additional resources to underperforming regions or sites so that underperformance attributable to a disproportionate concentration of patients with limited health literacy can be improved upon.

This approach to the allocation of resources extends to educational and communication initiatives. Health literate health care organizations provide an intensity and interactivity of communication that is proportional to the communication needs of the patients it is targeting. Curricular approaches, such as the “teach-to-goal” method described below (Baker et al., 2011b), is an example of distributing more educational resources (time and effort) to those who need more. Other strategies, such as automated

telephonic proactive outreach, can deliver more education and interaction between visits for those with greater communication needs, thereby helping patients achieve behavioral goals (Schillinger et al., 2008).

10. Employ a Higher Standard to Ensure Understanding of High-Risk Decisions and High-Risk Transitions

While promoting patient understanding through well-written health information, understandable verbal communication, and visual aids is a core value of health literate health care organizations, there are high-risk decisions in health care and important transitions that demand a heightened level of assurance that patients (or their surrogates, if the patient is not competent) fully understand. Health literate health care organizations often have identified which common decisions merit this degree of scrutiny and have standards and processes in place to ensure that comprehension has been accomplished, often by embedding health literacy practices, such as exposure to a standardized and well-designed teaching tool combined with successful demonstration (and documentation) of comprehension of key learning objectives using the teach-back method. Examples of high-risk circumstances include, but are not limited to, informed consent for surgery; administration of medications with serious complications or “black box” warnings, such as chemotherapy drugs, anticoagulants, immunosuppressive agents, or thrombolytic agents; and transitions in care, such as a discharge from the hospital. Hospital discharge processes can be improved by asking patients to “explain in your own words” the reason they were in the hospital and what they need to do to take care of themselves when they return home. Prior to surgery patients can be asked to “explain in your own words” the name of the surgery; the reason that it is being done; and the hoped-for benefits, likelihood of success, and possible risks. These responses offer an opportunity for continued dialogue and education around a critical moment. Patients’ responses can also be included in the consent and discharge paperwork as documentation of clear communication and comprehension. Efforts by the Iowa Health System that are highlighted in the AMA manual Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand provide an example of such a modified consent form (AMA, 2007b).

11. Prioritize Medication Safety and Medication Communication

A host of studies have shown that patients with low health literacy are more likely to misunderstand prescription drug labels (e.g., Wolf et al., 2007); that they have difficulty understanding drug warnings (Davis et al., 2006), using nonstandardized dosing instruments (Yin et al., 2007),

have difficulty effectively consolidating medication regimens if dosing instructions are variable (“every 12 hours” versus “twice a day”) (Sarkar et al., 2010b; Wolf et al., 2011a), and err in taking medication in the post-discharge context (unintentional non-adherence) (Lindquist et al., 2011) or in the diabetes context (severe hypoglycemia) (Sarkar et al., 2010b); and that they are less able to identify their medications (Kripalani et al., 2006). Additional factors, such as poor understanding regarding medication costs, changing formularies, nonstandard prescribing factors, confusion regarding generic and brand name labeling, and changing medication colors and shapes, make safe medication management even more difficult.

A health literate health care organization prioritizes medication safety by implementing systems and interventions that advance medication safety and self-management. In-person medication reconciliation, such as “brown-bag medication reviews,” provides an opportunity for patients to bring in all of their medications, including over-the-counter medications, and review how and why they take each of their medications. It is an opportunity for providers—including, but not limited to, pharmacists—to identify medication errors, such as duplicate medications; to reduce medication burden in the case of poly-pharmacy; and to identify patients who need extra time for medication teaching. Any provider trained with “show me” skills can help implement brown-bag reviews. The goals are not only to ensure that the regimen is accurate, but also to reinforce patients’ ability to answer the questions. How do I take my medicine, what is it for, and why is it important for me to take it? Health literate health care organizations recognize that medication reviews, if well done, are time-consuming and require incentivizing providers with the time and reimbursement to carry them out.

Health literate health care organizations establish internal guidelines on prescribing, including using standardized times and the consistent use of plain language, without abbreviations, in all medication prescriptions. Wolf and colleagues (2011b) have published promising work showing that standardized labels, with prescribing instructions centered around four standard time periods and universal language standards, can improve low-literacy patients’ ability to dose medications correctly and can improve their ability to consolidate complex regimens into more feasible daily schedules. Further advances in this field may be supported by changes in the national guidelines for prescription standards. Because research suggests that embedding visual aids (pill images) into medication counseling and labeling can reduce medication-taking errors (Machtinger et al., 2007), health literate health care organizations employ such visual aids to enhance safety.

Finally, recognizing that the complexities related to health insurance benefits and medication cost coverage and co-payments affect most pro-

foundly those with limited health literacy. Health literate health care organizations provide prescribing providers with up-to-date information regarding which medications are covered by a patient’s health insurance so as to reduce the likelihood that patients will have to unnecessarily navigate prior-authorization procedures. These organizations also provide staff and resources to patients to help them make decisions regarding medication options and drug plan options.

12. Make Health Plan and Health Insurance Products More Transparent and Comprehensible

As the health care industry becomes even more multi-sectoral, patients and their families are being asked to navigate choices and overcome barriers related to health insurance, health providers, and health services and to help in making a greater number of decisions regarding their care that go beyond traditional clinical decision making. As the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is put into effect, many Americans—a large portion of whom will have limited health literacy—will need to make decisions about health coverage plans. Decision making in the face of medical, financial, and administrative complexity will be overwhelming and burdensome for many. Ensuring that patients with limited health literacy successfully enroll is fundamental to the success of health care reform. Health literate health care organizations, including insurance plans, insurance exchanges, and pharmacy benefits management companies, provide information about benefits packages that is readily available to patients and their families, ensure that this information is understandable, and establish straightforward methods for patients and families to access in-person support for additional assistance.

Recently proposed regulations regarding the Health Insurance Exchange will assist patients in deciding between health insurance plans. The regulation requires that patients have access to an easy-to-understand summary of benefits and coverage and to a glossary of terms related to health insurance coverage (HHS, 2011; U.S. Department of Labor, 2011).

The California Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) recently partnered with the University of California–Berkeley School of Public Health to help seniors and people with disabilities understand their Medi-Cal health care choices, using participatory design to create a guidebook in English, Spanish, and Chinese that explains enrollment options and benefits. An evaluation showed that the guidebook increased understanding of enrollment options and the capacity to make choices (Neuhauser et al., 2009).

13. Make Systems More Navigable and Support Patients and Families in Navigating the Health Care System

Navigation within the health care system involves interacting with the built environment and finding one’s way between locations. In addition, it requires an ability to accomplish the myriad tasks needed to manage health within an increasingly complicated and fragmented medical system. It involves scheduling specialist appointments, enrolling for insurance services, understanding one’s health care benefits, dealing with pharmacy benefits management companies, finding locations for diagnostic studies, and connecting with community agencies. Health literate health care organizations work at establishing a shame-free environment so that patients and their families will be comfortable asking for help when needed. Employing clear signage and designing patient-friendly office procedures, including establishing a welcoming environment; offering assistance with all literacy-related tasks, such as reading and completing forms; and assisting patients with scheduling and finding referral and diagnostic test locations can help overcome these challenges.

Examples of design interventions that have made systems more navigable, especially for populations with limited health literacy, include electronic referrals to specialists (Kim-Hwang et al., 2010), which minimize the burden on patients to aggregate and master complex health information related to their consultations. Medical homes, with their promise of “one-stop-shopping,” can also simplify service delivery. The One-e-App program, an innovative web-based system, provides an efficient one-stop approach to enrollment in a range of public and private health, social service, and other support programs. One-e-App streamlines the application process through one electronic application that collects and stores information, screens and delivers data electronically, and helps families connect to needed services (California HealthCare Foundation, 2012).

Organization leadership can also enlist a team to perform an environmental assessment as a means of identifying areas in the built environment that may represent literacy barriers, such as poor or absent signage; absence of navigational guides, including maps; inconsistent labeling of locations and services; and lack of present and available personnel who can provide assistance (Rudd and Anderson, 2006; Sarkar et al., 2010a). These types of assessments are not just the responsibility of traditional health care delivery units (e.g., hospital or ambulatory clinic) but also of organizations in the health insurance industry, whose processes for enrollment, billing, prior authorization, and claims are notoriously difficult to navigate, often redundant, and generally confusing.

14. Recognize Social Needs as Medical Concerns and Connect People to Community Resources

Individuals with limited health literacy are often subject to other social vulnerabilities. These social needs, including housing instability, food insecurity, lack of transportation, unemployment, social isolation, legal concerns, and interpersonal violence, often have direct medical consequences and affect patients’ ability to effectively engage in self-management. However, members of the health team often miss the opportunity to assess patients for these conditions (Fleegler et al., 2007). Even when providers do identify social needs, health systems may not have the infrastructure and manpower to connect patients to needed social services.

There are some examples of efforts by health care organizations to partner with community resources. The Health Leads program (Health Leads, 2011; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2011), a volunteer-driven program based in outpatient clinics, allows medical providers to “prescribe” social service needs such as food, housing, and job training. The prescription is then “filled” by one of the college volunteers who work with patients to connect them with needed social services and who can continue to follow up in the event that there is additional need. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and AHRQ’s collaborative Prescription for Health initiative funded community-based projects to explore how primary care practices can make linkages with community resources to promote healthy behavior. While many of these projects were successful, an overall analysis of these programs suggests that sustaining linkages required continued communications between the health care system and the community resources and argues for a system in which clinical services and community services are integrated (Etz et al., 2008; Woolf et al., 2005). At a minimum health systems can develop a clearinghouse of local resources, identify members of the health care team to become champions in connecting with resources, and partner with case managers or social workers to assist with linking patients to resources.

Ultimately, unaddressed “non-health” social needs of patients will prevent patients from fully benefiting from the health care system and partnering in care. A health literate organization views linking patients with social resources as a fundamental part of providing medical care and ensures that there are systems in place to ensure that these connections are made.

15. Create a Climate in Which Asking Questions Is Encouraged and Expected

Patients with limited health literacy have been found to be less likely to ask questions of their providers or to have interactive communication in a visit. They may not disclose their challenges with reading and comprehension due to shame (Parikh et al., 1996). Interventions to “activate” patients to be more involved and to advocate for themselves hold promise as a means to increase the asking of questions and interactivity. Health literate health care organizations encourage and expect patients to be asking questions of their health care teams. The National Safety Foundation’s Ask Me 3 campaign attempts to facilitate communication between patients and providers by encouraging patients to ask the following questions:

1. What is my main problem?

2. What do I need to do?

3. Why is it important for me to do this? (National Patient Safety Foundation, n.d.)

Orienting providers to these questions, displaying posters, and distributing brochures encouraging the use of the Ask Me 3 questions may be an effective step in empowering patients to ask more questions, especially when it is linked with clinician training in health literacy, including the importance of minimizing patient shame (Mika et al., 2007). Additional resources, such as the AHRQ’s “Questions are the Answers” website (AHRQ, n.d.) can help patients formulate a list of questions to remember to ask their providers during a medical visit. Both of these initiatives can be strengthened by having allied members of the health care team encourage and remind patients to think of questions while preparing for their visits and to focus learning around these questions between visits.

16. Develop and Implement Curricula to Develop Mastery of a Threshold-Level Set of Knowledge and Skills

In order to improve skill building and to help patients reach behavioral goals as well as to track patient progress over time and across settings, health literate health care organizations develop curricular programs that acknowledge and are designed around the learning constraints related to patients’ working memory (generally a fixed capacity) and cognitive load (the learning demands, based on the complexities and quantity of the material). Baker and colleagues (2011b) describe six principles in helping patients achieve their learning goals:

1. Define a limited set of critical learning goals and eliminate all other information that does not directly support the learning goals.

2. Present information in discrete, predetermined “chunks.”

3. Determine the optimal order for teaching the topics.

4. Develop plain-language text to explain essential concepts for each goal, and employ appropriate graphics to increase comprehension and recall.

5. Confirm understanding after each unit, perform tailored instruction until mastery is attained, and review previously learned concepts until stable mastery is achieved.

6. Link all instruction to a specific attitude, skill, or behavioral goal.

These principles can be integrated into health-education initiatives in multiple health care settings being executed by a variety of providers, including physicians, nutritionists, pharmacists, health-at-home providers, and health educators. Having agreement on a shared curriculum can facilitate continued, consistent, and complementary education in different settings and across time to reinforce and build skills to approach mastery.

17. Continually Assess and Track Patient Comprehension, Skills, and Ability to Problem-Solve Around Health Conditions

While health literate health care organizations create “shame-free” environments where the asking of questions by patients is encouraged and expected, these organizations also build in procedures and systems to periodically assess and document patient comprehension and basic problem-solving skills across a range of common conditions that rely on self-management. Exemplar conditions include congestive heart failure, diabetes, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and anticoagulant care. Examples of skills and abilities important when dealing with heart failure include knowing one’s target weight, knowing what is involved in a daily self-check (e.g., leg swelling, weight change, changes in patterns of shortness of breath, and lightheadedness or dizziness), and knowing how to self-titrate one’s diuretic pill and when to call the medical home to prevent deterioration (Baker at al., 2011b; DeWalt et al., 2009). Examples pertaining to anticoagulant care for stroke prevention include knowing the signs and symptoms of stroke, knowing the recommended frequencies of blood testing and their meanings, accurately reporting one’s anticoagulant regimen, being aware that the anticoagulant medications interact with many others medications and therefore require vigilance, and recognizing the clinical relevance of bleeding (Fang et al., 2006). Such assessments can identify individuals at risk for poor comprehension, target immediate educational efforts, and provide an

indication for additional educational supports so that improvements or even mastery can be achieved over time. These assessments can also serve as valuable and dynamic information to share with the broader health care team working to improve a patient’s health literacy so that educational efforts reinforce, rather than compete with, each other and so that progress can be tracked. These efforts may also identify individuals with heretofore unrecognized and common learning barriers beyond limited literacy skills, such as cognitive impairment, learning disabilities, and hearing or visual impairment.

18. Recognize and Accommodate Additional Barriers to Communication

Limited health literacy is one of a number of common communication challenges patients face. Limited English proficiency, cognitive decline, hearing and visual impairment, learning disabilities, and mental health problems all may create barriers to clear communication. Many of these communication barriers travel together. When these challenges overlap, such barriers tend to compound or even overwhelm literacy-related obstacles (Sudore et al., 2009). A health literate health care organization prioritizes providing culturally and linguistically competent care and seeks to implement guidelines and recommendations for culturally and linguistically appropriate services (HHS, 2001). Health literate organizations recruit and cultivate a culturally and linguistically diverse staff and provide training in best practices working with medical interpreters for all members of the health care team. These organizations also have resources and procedures in place to identify and remediate hearing loss and visual impairment as well as to identify cognitive impairment that would require case management or engagement of surrogates and family caregivers.

CONCLUSION

Despite a growing understanding that health literacy challenges represent a mismatch between patients’ health literacy skills and the literacy demands of the greater health care system, until recently the majority of health literacy efforts have focused on interventions directed to the patient. The opportunities for systems redesign surrounding the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, including health insurance exchanges and Medicaid expansion, the advanced medical home, accountable care organizations, and health IT expansion, provide momentum for organizations to integrate principles of health literacy into organizational objectives, infrastructure, policies and practices, work-

force development, and communication strategies. In this paper, we introduce a set of attributes, goals, and foci for institutional investment that health literate health care organizations can embrace to begin to address the system-level factors that can prevent patients and families from fully benefiting from the health care system. This list of attributes and goals, which is by no means exhaustive, provides a roadmap for organizational change and relates most clearly to organizations that provide direct care to patients. However, a majority of the goals and attributes are also relevant to the broader range of organizations, stakeholders, and institutions that comprise the modern health care system. We see this paper less as the definitive response to the challenge of defining a “health literate health care organization” and more as an attempt to advance an optimistic vision of how organizations should evolve to be more responsive to the needs of populations with limited health literacy in tangible ways, thereby improving care for all.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research). n.d. Questions Are the Answer. http://www.ahrq.gov/questions/ (accessed March 21, 2012).

Allen, K., J. Zoellner, M. Motley, and P. A. Estabrooks. 2011. Understanding the internal and external validity of health literacy interventions: A systematic literature review using the RE-AIM framework. Journal of Health Communication 16(Suppl 3):55–72.

AMA (American Medical Association). 2007a. Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand (Manual for Clinicians). http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/367/healthlitclinicians.pdf (accessed March 21, 2012).

AMA. 2007b. Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/ama-foundation/our-programs/public-health/health-literacy-program/health-literacy-kit.

America’s Health Insurance Plans. n.d. Health Plan Organizational Assessment of Health Literacy Activities, Resource List—Health Plan Organizational Assessment of Health Literacy Activities, and Suggestions for Areas of Improvement. http://www.ahip.org/content/default.aspx?docid=29467.

Baker, D. W., R. M. Parker, M. V. Williams, W. S. Clark, and J. Nurss. 1997. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. American Journal of Public Health 87(6):1027–1030.

Baker, D. W., J. A. Gazmararian, M. V. Williams, T. Scott, R. M. Parker, D. Green, J. Ren, and J. Peel. 2002. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. American Journal of Public Health 92(8):1278–1283.

Baker, D. W., D. A. Dewalt, D. Schillinger, V. Hawk, B. Ruo, K. Bibbins-Domingo, M. Weinberger, A. Macabasco-O’Connell, K. L. Grady, G. M. Holmes, B. Erman, K. A. Broucksou, and M. Pignone. 2011a. The effect of progressive, reinforcing telephone education and counseling versus brief educational intervention on knowledge, self-care behaviors and heart failure symptoms. Journal of Cardiac Failure 17(10):789–796.

Baker, D. W., D. A. Dewalt, D. Schillinger, V. Hawk, B. Ruo, K. Bibbins-Domingo, M. Weinberger, A. Macabasco-O’Connell, and M. Pignone. 2011b. “Teach to goal”: Theory and design principles of an intervention to improve heart failure self-management skills of patients with low health literacy. Journal of Health Communication 16(Suppl 3):73–88.

Belkora, J. K., A. Teng, S. Volz, M. K. Loth, and L. J. Esserman. 2011a. Expanding the reach of decision and communication aids in a breast care center: A quality improvement study. Patient Education and Counseling 83(2):234–239.

Belkora, J. K., S. Volz, A. E. Teng, D. H. Moore, M. K. Loth, and K. R. Sepucha. 2011b. Impact of decision aids in a sustained implementation at a breast care center. Patient Education and Counseling 86(2):195–204.

Bickmore, T. W., L. M. Pfeifer, and M. K. Paasche-Orlow. 2009. Using computer agents to explain medical documents to patients with low health literacy. Patient Education and Counseling 75(3):315–320.

California HealthCare Foundation. 2012. One-e-App: One-Stop Access to Health and Social Service Programs. http://www.chcf.org/projects/2007/oneeapp-onestop-access-to-health-care (accessed March 21, 2012).

Cavanaugh, K., M. M. Huizinga, K. A. Wallston, T. Gebretsadik, A. Shintani, D. Davis, R. P. Gregory, L. Fuchs, R. Malone, A. Cherrington, M. Pignone, D. A. DeWalt, T. A. Elasy, and R. L. Rothman. 2008. Association of numeracy and diabetes control. Annals of Internal Medicine 148(10):737–746.

Davis, T. C., M. S. Wolf, P. F. Bass, 3rd, M. Middlebrooks, E. Kennen, D. W. Baker, C. L. Bennett, R. Durazo-Arvizu, A. Bocchini, S. Savory, and R. M. Parker. 2006. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(8):847–851.

DeWalt, D. A., K. A. Broucksou, V. Hawk, D. W. Baker, D. Schillinger, B. Ruo, K. Bibbins-Domingo, M. Holmes, M. Weinberger, A. Macabasco-O’Connell, and M. Pignone. 2009. Comparison of a one-time educational intervention to a teach-to-goal educational intervention for self-management of heart failure: Design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research 9:99. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2702288/?tool=pubmed (accessed March 21, 2012).

DeWalt, D. A., L. F. Callahan, V. H. Hawk, K. A. Broucksou, A. Hink, R. Rudd, and C. Brach. 2010. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. Prepared for Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/literacy/healthliteracytoolkit.pdf (accessed March 21, 2012).

Eichner, J, and P. Dullabh. 2007. Accessible Health Information Technology (Health IT) for Populations with Limited Literacy: A Guide for Developers and Purchasers of Health IT. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Etz, R. S., D. J. Cohen, S. H. Woolf, J. Summers Holtrop, K. E. Donahue, N. F. Isaacson, K. C. Stange, R. L. Ferrer, and A. L. Olson. 2008. Bridging primary care practices and communities to promote healthy behaviors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35(5 Suppl):S390–S397.

Fang, M. C., E. L. Machtinger, F. Wang, and D. Schillinger. 2006. Health literacy and anticoagulation-related outcomes among patients taking warfarin. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(8):841–846.

Fleegler, E. W., T. A. Lieu, P. H. Wise, and S. Muret-Wagstaff. 2007. Families’ health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics 119(6):e1332–e1341.

Gazmararian, J. A., K. Beditz, S. Pisano, and R. Carreon. 2010. The development of a health literacy assessment tool for health plans. Journal of Health Communication 15(Suppl 2):93–101.

Hardie, N. A., K. Kyanko, S. Busch, A. T. Losasso, and R. A. Levin. 2011. Health literacy and health care spending and utilization in a consumer-driven health plan. Journal of Health Communication 16(Suppl 3):308–321.

Health Leads. 2011. A New Vision for Healthcare in America. http://www.healthleadsusa.org/ (accessed March 21, 2012).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2001. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

HHS. 2010. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.health.gov/communication/HLActionPlan/ (accessed March 21, 2012).

HHS. 2011. Providing Clear and Consistent Information to Consumers about Their Health Insurance Coverage. http://www.healthcare.gov/news/factsheets/2011/08/labels08172011a.html (accessed March 12, 2012).

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). n.d. Unified Health Communication (UHC): Addressing Health Literacy, Cultural Competency, and Limited English Proficiency. http://www.hrsa.gov/publichealth/healthliteracy/index.html (accessed March 21, 2012).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2004. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Edited by L. Nielsen-Bohlman, A. Panzer, and D. A. Kindig. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jacobson, K. L., J. A. Gazmararian, S. Kripalani, K. J. McMorris, S. C. Blake, and C. Brach. 2007. Is Our Pharmacy Meeting Patients’ Needs? A Pharmacy Health Literacy Assessment Tool User’s Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Joint Commission. 2007. What Did the Doctor Say? Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety. http://www.jointcommission.org/What_Did_the_Doctor_Say/ (accessed March 21, 2012).

Kim-Hwang, J. E., A. H. Chen, D. S. Bell, D. Guzman, H. F. Yee, Jr., and M. B. Kushel. 2010. Evaluating electronic referrals for specialty care at a public hospital. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25(10):1123–1128.

Kripalani, S., L. E. Henderson, E. Y. Chiu, R. Robertson, P. Kolm, and T. A. Jacobson. 2006. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(8):852–856.

Lindquist, L. A., L. Go, J. Fleisher, N. Jain, E. Friesema, and D. W. Baker. 2011. Relationship of health literacy to intentional and unintentional non-adherence of hospital discharge medications. Journal of General Internal Medicine 27(2):173–178.

Machtinger, E. L., F. Wang, L.-L. Chen, M. Rodriguez, S. Wu, and D. Schillinger. 2007. A visual medication schedule to improve anticoagulation control: A randomized, controlled trial. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety/Joint Commission Resources 33(10):625–635.

Martin, L. T., and R. M. Parker. 2011. Insurance expansion and health literacy. JAMA 306(8):874–875.

Mika, V. S., P. R. Wood, B. D. Weiss, and L. Treviño. 2007. Ask Me 3: Improving communication in a Hispanic pediatric outpatient practice. American Journal of Health Behavior 31(Suppl 1):S115–S121.

National Center for Education Statistics. 2006. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

National Patient Safety Foundation. n.d. Ask Me 3. Available from http://www.npsf.org/askme3/ (accessed March 21, 2012).

National Quality Forum. 2005. Improving Patient Safety Through Informed Consent for Patients with Limited Health Literacy. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum.

National Quality Forum. 2009 (March). Health Literacy: A Linchpin in Achieving National Goals for Health and Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum.

National Quality Forum. 2010. Safe Practices for Better Healthcare—2010 Update. Washington DC: National Quality Forum.

NCI (National Cancer Institute). 1994. Clear & Simple: Developing Effective Print Materials for Low-Literate Readers. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Neuhauser, L., B. Rothschild, C. Graham, S. L. Ivey, and S. Konishi. 2009. Participatory design of mass health communication in three languages for seniors and people with disabilities on Medicaid. American Journal of Public Health 99(12):2188–2195.

New York New Jersey Public Health Training Center. 2011. Health Literacy & Public Health: Strategies for Addressing Low Health Literacy. http://www.nynj-phtc.org/pages/catalog/phlit02/ (accessed March 21, 2012).

NLM (National Library of Medicine). 2012. Easy-to-Read Health Materials. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/all_easytoread.html (accessed March 21, 2012).

Norman, C. D., and H. A. Skinner. 2006. eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. Journal of Medical Internet Research 8(4):e27–e27.

Parikh, N. S., R. M. Parker, J. R. Nurss, D. W. Baker, and M. V. Williams. 1996. Shame and health literacy: The unspoken connection. Patient Education and Counseling 27(1):33–39.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2011. An Innovative Prescription for Better Health. http://www.rwjf.org/vulnerablepopulations/product.jsp?id=72319 (accessed March 21, 2012).

Rothman, R. L., D. A. DeWalt, R. Malone, B. Bryant, A. Shintani, B. Crigler, M. Weinberger, and M. Pignone. 2004. Influence of patient literacy on the effectiveness of a primary care-based diabetes disease management program. JAMA 292(14):1711–1716.

Rudd, R., and J. Anderson. 2006. The Health Literacy Environment of Hospitals and Health Centers. National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy 2006. http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/healthliteracy/files/healthliteracyenvironment.pdf (accessed March 21, 2012)

Sarkar, U., J. D. Piette, R. Gonzales, D. Lessler, L. D. Chew, B. Reilly, J. Johnson, M. Brunt, J. Huang, M. Regenstein, and D. Schillinger. 2008. Preferences for self-management support: Findings from a survey of diabetes patients in safety-net health systems. Patient Education and Counseling 70(1):102–110.

Sarkar, U., A. J. Karter, J. Y. Liu, N. E. Adler, R. Nguyen, A. Lopez, and D. Schillinger. 2010a. The literacy divide: Health literacy and the use of an Internet-based patient portal in an integrated health system-results from The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Journal of Health Communication 15(Suppl 2):183–196.

Sarkar, U., A. J. Karter, J. Y. Liu, H. H. Moffet, N. E. Adler, and D. Schillinger. 2010b. Hypoglycemia is more common among type 2 diabetes patients with limited health literacy: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Journal of General Internal Medicine 25(9):962–968.

Sarkar, U., D. Schillinger, K. Bibbins–Domingo, A. Nápoles, L. Karliner, and E. J. Pérez-Stable. 2011. Patient-physicians’ information exchange in outpatient cardiac care: Time for a heart to heart? Patient Education and Counseling 85(2):173–179.

Schillinger, D. 2007. Literacy and health communication: Reversing the “inverse care law.” The American Journal of Bioethics 7(11):15–18; discussion W1–W2.

Schillinger, D., K. Grumbach, J. Piette, F. Wang, D. Osmond, C. Daher, J. Palacios, G. D. Sullivan, and A. B. Bindman. 2002. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 288(4):475–482.

Schillinger, D., J. Piette, K. Grumbach, F. Wang, C. Wilson, C. Daher, K. Leong-Grotz, C. Castro, and A. B. Bindman. 2003. Closing the loop: Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Archives of Internal Medicine 163(1):83–90.

Schillinger, D., A. Bindman, F. Wang, A. Stewart, and J. Piette. 2004. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Education and Counseling 52(3):315–323.

Schillinger, D., E. L. Machtinger, F. Wang, L. L. Chen, K. Win, J. Palacios, M. Rodriguez, and A. Bindman. 2005. Language, literacy, and communication regarding medication in an anticoagulation clinic: Are pictures better than words? In K. Henriksen, J. B. Battles, E. S. Marks, and D. I. Lewin, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation, Vol. 2: Concepts and Methodology (pp. 199–212). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Schillinger, D., H. Hammer, F. Wang, J. Palacios, I. McLean, A. Tang, S. Youmans, and M. Handley. 2008. Seeing in 3-D: Examining the reach of diabetes self-management support strategies in a public health care system. Health Education & Behavior 35(5):664–682.

Schillinger, D., M. Handley, F. Wang, and H. Hammer. 2009. Effects of self-management support on structure, process, and outcomes among vulnerable patients with diabetes: A three-arm practical clinical trial. Diabetes Care 32(4):559–566.

Sheridan, S. L., D. J. Halpern, A. J. Viera, N. D. Berkman, K. E. Donahue, and K. Crotty. 2011. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: A systematic review. Journal of Health Communication 16(Suppl 3):30–54.

Sommers, B. D., and A. M. Epstein. 2010. Medicaid expansion—the soft underbelly of health care reform? New England Journal of Medicine 363(22):2085–2087.

Sudore, R. L., K. Yaffe, S. Satterfield, T. B. Harris, K. M. Mehta, E. M. Simonsick, A. B. Newman, C. Rosano, R. Rooks, S. M. Rubin, H. N. Ayonayon, and D. Schillinger. 2006. Limited literacy and mortality in the elderly: The health, aging, and body composition study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(8):806–812.

Sudore, R. L., C. S. Landefeld, E. J. Perez-Stable, K. Bibbins-Domingo, B. A. Williams, and D. Schillinger. 2009. Unraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient–physician communication. Patient Education and Counseling 75(3):398–402.

U.S. Department of Labor. 2011. New Affordable Care Act Proposal to Help Consumers Better Understand and Compare Benefits and Coverage. http://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/ebsa/EBSA20111232.htm (accessed March 21, 2012).

U.S. Surgeon General. 2006. Paper read at the Surgeon General’s Workshop on Improving Health Literacy, September 7, at National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Vernon, J., A. Trujillo, S. Rosenbaum, and B. DeBuono. 2007. Low Health Literacy: Implications for National Health Policy. National Patient Safety Foundation. http://www.gwumc.edu/sphhs/departments/healthpolicy/CHPR/downloads/LowHealthLiteracyReport10_4_07.pdf (accessed March 21, 2012).

Volandes, A. E., L. S. Lehmann, E. F. Cook, S. Shaykevich, E. D. Abbo, and M. R. Gillick. 2007. Using video images of dementia in advance care planning. Archives of Internal Medicine 167(8):828–833.

Volandes, A. E., M. J. Barry, Y. Chang, and M. K. Paasche-Orlow. 2010. Improving decision making at the end of life with video images. Medical Decision Making 30(1):29–34.

Williams, M. V., D. W. Baker, E. G. Honig, T. M. Lee, and A. Nowlan. 1998. Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest 114(4):1008–1015.

Wolf, M. S., T. C. Davis, W. Shrank, D. N. Rapp, P. F. Bass, U. M. Connor, M. Clayman, and R. M. Parker. 2007. To err is human: Patient misinterpretations of prescription drug label instructions. Patient Education and Counseling 67(3):293–300.

Wolf, M. S., L. M. Curtis, K. Waite, S. C. Bailey, L. A. Hedlund, T. C. Davis, W. H. Shrank, R. M. Parker, and A. J. J. Wood. 2011a. Helping patients simplify and safely use complex prescription regimens. Archives of Internal Medicine 171(4):300–305.

Wolf, M. S., T. C. Davis, L. M. Curtis, J. A. Webb, S. C. Bailey, W. H. Shrank, L. Lindquist, B. Ruo, M. V. Bocchini, R. M. Parker, and A. J. J. Wood. 2011b. Effect of standardized, patient-centered label instructions to improve comprehension of prescription drug use. Medical Care 49(1):96–100.

Woolf, S. H., R. E. Glasgow, A. Krist, C. Bartz, S. A. Flocke, J. S. Holtrop, S. F. Rothemich, and E. R. Wald. 2005. Putting it together: Finding success in behavior change through integration of services. Annals of Family Medicine 3(Suppl 2):S20–S27.

Wynia, M. K., M. Johnson, T. P. McCoy, L. P. Griffin, and C. Y. Osborn. 2010. Validation of an organizational communication climate assessment toolkit. American Journal of Medical Quality 25(6):436–443.

Yin, H. S., B. P. Dreyer, G. Foltin, L. van Schaick, and A. L. Mendelsohn. 2007. Association of low caregiver health literacy with reported use of nonstandardized dosing instruments and lack of knowledge of weight-based dosing. Ambulatory Pediatrics 7(4):292–298.