This chapter presents the framework established by the panel for evaluating the use of estimates based on American Community Survey (ACS) data, describes the data and information sources and how they were used, and provides an overview of the panel’s evaluation approach. It also presents intermediate results, such as those related to the use of ACS variables to define eligible students. Results of comparisons of estimates from alternative data sources are presented in Chapter 4.

The key variables of interest for this study are the percentages of students eligible or certified for free, reduced-price, and full-price meals and the percentages of meals served to students in each eligibility category. These are the eligibility, certification, and participation percentages shown in Figure 2-1 in Chapter 2. Estimates that can be computed from the ACS are eligibility rates (with eligibility determined using ACS variables), while estimates that can be computed from administrative data are certification rates that reflect students applying and being approved or directly certified through the application, certification, and verification processes. An ultimate goal is the determination of claiming percentages that reflect participation—meals served by category—under a universal feeding option, also shown in Figure 2-1.

While the panel analyzed all eligibility, certification, and participation percentages (free, reduced price, and full price), we focused on the blended reimbursement rate (BRR) described as part of the reimbursement equations presented in Chapter 2. Looking at changes in the free, reduced-price, and full-price percentages individually can be confusing because

they are correlated, making the impact of changes difficult to assess. The advantage of the BRR is that it depends on all three percentages in a way that is of most direct interest to districts. Specifically, it gives the impact of changes in the percentages on the bottom line— reimbursement. In fact, it is the average reimbursement per meal. The BRR is especially useful as a summary measure for ascertaining the differences in reimbursement that result from using different percentage distributions (eligible students, certified students, or meals served) as claiming percentages. Nonetheless, workshop participants told the panel that to consider participating in the ACS Eligibility Option (AEO), they would need to see all estimates (percentages of students eligible for free, reduced-price, and full-price meals) in addition to the BRR and claiming percentages to help them assess whether to adopt the AEO.1

The panel’s analytical results are focused throughout on school districts in which more than 75 percent of students were eligible for free or reduced-price meals in any school year from 2004-2005 through 2009-2010 because these districts are most likely to be interested in the AEO dis-trictwide. We call these districts “very high FRPL [free or reduced-price lunch].”2Table 3-1 shows the distribution of these and other districts by size for all districts that have school meals program certification data for school year 2009-2010 from the Common Core of Data (CCD) and for which the Census Bureau derived ACS estimates. There are 1,291 such districts in the nation (about 10 percent of all districts), which enrolled nearly 13 percent of all students and 22 percent of students certified for

____________

1 Many of our analyses examine the individual free, reduced-price, and full-price percent ages. As noted, however, the BRR is a useful way to summarize these percentages and focus attention on whether different sets of percentages substantially affect reimbursement, given that the difference of $.40 (currently) between the free and reduced-price meal reimburse ment rates is very small relative to the difference of more than $2 between those rates and the rate for full-price meals. Based on the lunch reimbursement rates (with the $.02 increment) for 2010-2011 (see Table 2-6 in Chapter 2), the BRR with free, reduced-price, and full-price eligibility percentages of 80, 5, and 15 percent, respectively, is less than 2 percent higher than the BRR with percentages of 70, 15, and 15 percent, respectively ($2.3510 versus $2.3110). In contrast, the latter is nearly 10 percent greater than the BRR with percentages of 70, 5, and 25 percent ($2.1050). In other words, shifting 10 percent (of students or meals) from the reduced-price category to the full-price category has a much greater effect on reimbursement than shifting them to the free category. The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 explicitly acknowledges the BRR as a useful measure for analysis and decision making, requiring states to calculate and disseminate BRRs for districts for purposes of implementing and administering the Community Eligibility Option.

2 The 75 percent figure was identified as a threshold for potential interest in a universal feed ing provision in many phases of the panel’s analysis. It is noted in publications by the Food Research and Action Center (see http://frac.org/newsite/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/provision2.pdf). As discussed later, the 75 percent threshold also was mentioned by partici pants in the panel’s workshop and in its survey of Provision 2/3 districts.

TABLE 3-1 Number and Percentage of U.S. School Districts* by Size and Percentage Approved for Free or Reduced-Price Meals

|

|

||||

| Size | Low FRPL | High FRPL | Very High FRPL | |

|

|

||||

| Large | Number of districts | 468 | 305 | 110 |

| Percentage of districts | 3.6 | 2.4 | 0.9 | |

| Percentage of enrollment | 24.1 | 19.2 | 8.7 | |

| Medium | Number of districts | 1,415 | 722 | 187 |

| Percentage of districts | 10.9 | 5.6 | 1.4 | |

| Percentage of enrollment | 16.0 | 8.4 | 2.1 | |

| Small | Number of districts | 5,645 | 3,092 | 994 |

| Percentage of districts | 43.6 | 23.9 | 7.7 | |

| Percentage of enrollment | 12.9 | 6.6 | 1.9 | |

| Total | Number of districts | 7,528 | 4,119 | 1,291 |

| Percentage of districts | 58.2 | 31.8 | 10.0 | |

| Percentage of enrollment | 52.9 | 34.1 | 12.8 | |

|

|

||||

NOTE: FRPL = free or reduced-price lunch.

*All school districts in the United States with Common Core of Data (CCD) free or reduced-price meals certifcation data for 2009-2010 and American Community Survey (ACS) estimates. Large districts have 1-year estimates. Medium-sized districts have 3-year estimates, but do not have 1-year estimates. Small districts have only 5-year estimates.

SOURCE: Prepared by the panel.

free or reduced-price meals. We also considered districts with more than 50 percent but never more than 75 percent of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals in the school years from 2004-2005 through 2009-2010 because these districts might be interested in the AEO for a subset of schools. We call these districts “high FRPL.” There are 4,119 such districts nationwide (32 percent of districts), enrolling 34 percent of all students and 44 percent of students certified for free or reduced-price meals.

The data collected on form FNS-742 (described in more detail later) show that only 431 of these school districts were operating under Provision 2 or 3, not in a base year, in 2009-2010. Of these, 296 were operating under Provision 2 or 3 districtwide, and 135 were operating under Provision 2 or 3 for only some schools. Of those operating under Provision 2 or 3 districtwide, 79 percent had an FRPL percentage greater than or equal to 75, 10 percent had an FRPL percentage greater than or equal to 50 but less than 75, and 12 percent had an FRPL percentage less than 50. Of the districts where Provision 2 or 3 was implemented for only some schools, 32 percent had a district-level FRPL percentage greater than or equal to 75, 45 percent had an FRPL percentage greater than or equal to 50 percent but less than 75, and 23 percent had an FRPL percentage less than 50. We also refer to districts as large, medium, and small, depending on whether they had 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year ACS direct estimates available (population

of at least 65,000); 3-year and 5-year (but not 1-year) estimates available (population between 20,000 and 64,999); or only 5-year estimates available (population under 20,000).

SOURCES OF DATA ON ELIGIBILITY AND PARTICIPATION

The ACS is the only national survey that may be large enough for use in estimating numbers of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals in school districts and school attendance areas under a potential new provision. The panel considered the use of estimates from the ACS in terms of their accuracy, timeliness, and geographic coverage. Assessment of these properties and the development of possible corrections for any shortcomings required comparison with additional data sources and data products. This section begins with a description of the ACS direct and model-based estimates and then describes the other data sources the panel compared with the ACS: the administrative data collected by the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) in support of the school meals programs, administrative information about schools and school districts collected and provided by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) in the CCD, and school-level data provided to the panel by our case study districts. These data sources were used to assess not only any systematic differences between ACS and administrative estimates, but also the precision, temporal stability, and timeliness of ACS estimates for all school districts in the country and for the schools in our case study districts.

The American Community Survey

The ACS is a continuous survey used to collect data on income, family composition, and other individual and household characteristics that previously were gathered once every 10 years from the long-form sample of the decennial census of population. After a decade of testing and development, the ACS became fully operational in 2005 for households; people living in group quarters were added beginning in 2006. With the advent of the ACS, the 2010 census (as will be true of future censuses) included only the short-form items of age, sex, race, ethnicity, relationship to householder, and owner/renter status (see National Research Council, 2007).

The ACS samples about 240,000 housing unit addresses every month from the Census Bureau’s Master Address File, for a total of nearly 2.9 million housing unit addresses every year (increased to 295,000 addresses per month in June 2011). Each month, about half of the households receiving a questionnaire in the mail fill it out and mail it back; nonresponding households for which telephone numbers can be obtained are contacted using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). A one-third sam-

ple (approximately) of the remaining nonrespondents is designated for follow-up using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI). High overall response rates have been achieved for the ACS. The response rate, obtained by adding mailback and CATI respondents together with a weighted estimate of respondents in the CAPI subsample, was approximately 98 percent in 2009.3

The goal of the ACS is to provide small-area estimates similar in precision to but more timely than those provided by the census long-form sample. Because the ACS sample is spread out over time, the data must be accumulated over months and years to provide reliable estimates for small areas. In late 2006 (for calendar year 2005), the Census Bureau began releasing ACS 1-year estimates for states, counties, cities, school districts, and other geographic areas with at least 65,000 people. In late 2008, the Census Bureau began releasing ACS 3-year estimates for areas with at least 20,000 people. Finally, in late 2010, the Census Bureau began releasing ACS 5-year estimates for all geographic areas in Census Bureau databases, including block groups, census tracts, small cities, towns, and school districts.

The ACS data provide an opportunity to construct estimates of students who are eligible for free, reduced-price, and full-price meals for the attendance areas of schools, groups of schools, and school districts. Most school districts in the United States are small in population size. Thus of the 13,777 school districts for which ACS estimates were released in fall 2011, only 985 had 65,000 or more residents according to the July 2010 Census Bureau population estimates, and only 3,411 had more than 20,000 residents.4 Moreover, even in medium-sized and large school districts, attendance areas for individual schools or groups of schools are small. Because ACS estimates are not provided for school attendance areas, estimates for these areas would need to be based on boundary information or lists of census blocks provided to the Census Bureau by a state or local education agency.

Numerous challenges must be addressed before the ACS can be used to derive eligibility estimates and establish claiming percentages for the school meals programs. Five of the most important issues are (1) constructing geographic areas to represent school attendance areas; (2) determining eligibility using ACS variables; (3) assessing systematic differences between ACS and administrative estimates; (4) assessing levels of variability, temporal stability, and timeliness; and (5) accounting for participation. Subsequent sections of this chapter address the first two issues and outline the empirical analyses needed to address the last three. Results of the data comparisons and analyses are provided in Chapter 4.

____________

3 See http://www.census.gov/acs/www/methodology/sample_size_and_data_quality/.

4 See http://www.census.gov/acs/www/data_documentation/areas_published/.

Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) and ACS Model-Based Estimates

The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 directed the U.S. Department of Education to distribute Title I basic and concentration grants directly to school districts on the basis of the most recent estimates of school-age children in poverty available from the Census Bureau. These estimates, from the SAIPE Program, were first developed in the late 1990s (see National Research Council, 2000a,b) and are currently based on data from the ACS, the 2000 census, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program), aggregated federal income tax data, and a series of statistical models. The 2009 and 2010 SAIPE estimates correspond to 2009-2010 school district boundaries.

Annual SAIPE estimates of related children aged 5-17 living in families with income below the poverty line are used in allocating $14 billion to school districts for Title I of the No Child Left Behind Act.5 The school district estimation process uses the number of school-age children in poverty in a county estimated from a statistical model and the estimated number of children in households below the poverty line based on federal income tax returns for each school district (or part of a district) in that county. The county-level model combines the results of a regression equation with direct (not model-based) 1-year ACS estimates, controlled to estimates from a state-level model. The county- and state-level regression equations use administrative records data and estimates from the 2000 census long-form sample to predict numbers of school-age children living in poverty for each county or state.6

The SAIPE model estimates are produced for a given year with about a 1-year time lag; for example, the 2009 estimates were released in December 2010, incorporating administrative records information for 2008. This timing is only a few months later than the release of direct ACS estimates. As a result, SAIPE estimates are considerably more timely than the 5-year ACS estimates, the only other available option for small school districts. The SAIPE model-based estimates have the advantage of reducing mean-squared error relative to direct estimates for small geographic areas; however, their accuracy depends on the validity of the underlying model and

____________

5 Related children are people under age 18 and related by birth, marriage, or adoption to the householder of the housing unit in which they reside; foster children, other unrelated individuals under age 18, and residents of group quarters under age 18 are not considered related children.

6 It will not be possible to update the 2000 census variables in the state and county models because the 2010 census ascertained only basic demographic information on households, with the ACS obtaining the detailed socioeconomic data formerly included on the census long form.

may vary for different kinds of areas. SAIPE estimates are not available for census tracts or block groups, and they pertain to the official statistical poverty level and not the 130 percent and 185 percent ratios of income to the poverty guidelines that determine eligibility for free or reduced-price school meals, respectively.

The panel collaborated with the Census Bureau, which agreed to adapt the SAIPE approach and provide model-based ACS estimates of the percentages of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals in each school district in the United States and in the school attendance areas in the case study districts. The methodology developed to provide these model-based estimates is described in Appendix C, and the estimates are evaluated in Chapter 4.

Administrative Data

Both FNS and NCES in the Department of Education collect data from school districts nationwide that can be considered a benchmark for comparisons with the estimates from the ACS. FNS has two relevant data collection mechanisms—form FNS-742, School Food Authority Verification Summary Report (information for school districts), and form FNS-10, Report of School Program Operations (information at the state level only). NCES provides detailed information through the CCD, including data on enrollment, number of students certified for free meals, and number certified for reduced-price meals, for all public school districts and public schools in the country. The panel also collected detailed administrative data concerning enrollment, certification, and meals served from our five case study districts.

Form FNS-7427 collects data on verification activities. With few exceptions, each school district that operates the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) or School Breakfast Program (SBP) must report the information on this form annually. Section I of the form obtains information as of the last operating day in October. Included are the number of schools operating the NSLP or SBP and the enrollment of those schools, the total number of free-certified and reduced-price-certified students, and the number of free-certified students who are separately identified as (1) not subject to verification (directly certified, homeless liaison list, income-eligible Head Start, pre-K Even Start, students in residential child care institutions [RCCIs], and nonapplicants approved by local officials); (2) certified based on a SNAP, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), or Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) case number submitted on an application; (3) certified based on income

____________

7 The form is available at http://www.fns.usda.gov/fns/forms.htm.

reported on an application; and (4) certified in Provision 2 and 3 schools not operating in a base year. The number of reduced-price-certified students also is separately identified for Provision 2 and 3 schools not operating in a base year.

Section II of form FNS-742 provides information about verification. The reported outcomes of verification include no change, responded and changed to free, responded and changed to reduced price, responded and changed to full price, did not respond, and reapplied and was reapproved on or before February 15. For each outcome, three counts are reported: the number of free-certified students based on the SNAP/ TANF/FDPIR case number submitted on the application; the number of free-certified students based on income provided on the application; and the number of reduced-price-certified students based on income. The form also collects data on the number of applications and the number of students for each outcome. Data from form FNS-742 are maintained by FNS and are used to prepare summary reports of verification activities.

Form FNS-10 collects state-level counts related to the school meals programs and is completed by state agencies. The form has two parts. Part A, which must be submitted monthly, obtains the number of meals served in the state under the NSLP and SBP by category (free, reduced price, full price), the total number of meals, and the average daily number of meals. This information is used to compute state-level reimbursements for the school meals programs. Part B is to be completed once a year. In October, states report the number of meals served by category in private schools and RCCIs. Also included are counts of public schools, private schools, and RCCIs that participate in the school meals programs (by program) and the enrollment of those schools. For the NSLP, the form shows the number of students approved for free lunches and the number approved for reduced-price lunches.

To complete form FNS-10, a state agency obtains the necessary information from school districts. Data must be kept for 3 years. FNS provides summary information on its website at http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/cnpmain.htm. Form FNS-10 was the only comprehensive source of participation information available to the panel, but as noted, it is available only at the state level.

The CCD, a program of NCES, conducts five census operations annually to collect fiscal and nonfiscal data on all public schools, public school districts, and state education agencies in the United States. It provides an official listing of public elementary and secondary schools and school districts in the nation, which is used to select samples for other NCES surveys, and it provides basic information and descriptive statistics on public elementary and secondary schools and schooling in general. The data, supplied by state education agency officials,

include information about schools and school districts: name, address, and phone number; information about students and staff, including demographic characteristics; and fiscal data, including revenues and current expenditures. Most of these data are obtained from administrative records, presumably the same ones used by states as the basis for completing FNS forms.

For purposes of this study, the most relevant data from the CCD are the school and school district counts of enrolled students and numbers of students certified for free- and reduced-price meals. The CCD also contains demographic variables (race and ethnicity, English-language-learner status) that were used in the panel’s analysis.

Case Study Districts

The panel invited six school districts to participate in this study as case studies, and five agreed. A district could be considered for participation if it had taken applications for the school meals programs for all schools in the district for the past 5 years, had no outstanding counting/ claiming issues, was willing and able to provide digitized boundaries for the attendance areas for each school, and was willing to provide an extensive amount of school-level data for up to 6 school years.

The panel decided that case studies should be selected from districts with “medium need,” that is, free or reduced-price percentages of 50 to 75 percent. Another criterion was that the districts should be “heterogeneous,” that is, have at least 25 percent of schools with free or reduced-price percentages of more than 75 percent and at least 25 percent of schools with free or reduced-price percentages of less than 50 percent. The intent was to identify school districts that were likely to consider adopting the AEO for only a subset of schools. From among such districts, we wanted ones that varied in terms of enrollment but were not so small that estimates for schools or groups of schools would be too imprecise. As a rough guide, we chose to consider only the 65 medium-need, heterogeneous school districts with enrollment greater than 12,000 students based on CCD data for 2007-2008. Within this group, we planned to select 4 large school districts (enrollment of at least 25,000) and 2 medium-sized school districts (enrollment between 12,000 and 25,000). The resulting list of potential case study districts was further refined on the basis of diversity in the aggregate level of need for free and reduced-price meals, diversity in the pattern of heterogeneity of need across schools, available information about state and district management and program operations, geographic diversity, and diversity in the race and ethnicity of students. The five school districts listed in Table 3-2 agreed to participate as case study districts: Austin, Texas;

TABLE 3-2 Case Study Districts

|

|

|||

| School District | Number of Participating Schools | Number of Students (in thousands) | Students in Schools Without Boundaries (percentage of enrolled)* |

|

|

|||

| Austin, Texas | 114 | 83 | 3.0 |

| Chatham County, Georgia | 46 | 35 | 5.4 |

| Norfolk, Virginia | 56 | 36 | 10.0 |

| Omaha, Nebraska | 86 | 47 | 4.6 |

| Pajaro Valley, California | 32 | 19 | 7.4 |

|

|

|||

*Omaha and Chatham County are also open enrollment districts. In open enrollment districts, many schools have geographic boundaries, but students are not required to attend neighborhood schools.

SOURCE: Prepared by the panel.

Chatham County,8 Georgia; Norfolk, Virginia; Omaha, Nebraska; and Pajaro Valley, California.

The panel contacted state directors in the states of the potential case study districts to describe the study and ask for their assistance. With the approval of state directors, we contacted school district staff. To facilitate the development of the case studies, we obtained the support of the School Nutrition Association (SNA). The president of SNA, Dora Rivas, wrote a letter in support of the study that was included with our letters to state directors and to school district officials.

From each case study district, the panel obtained digitized boundaries for school attendance areas for the most recent school year and detailed data for each school on enrollment, students approved for free and reduced-price meals, and reimbursable meals served under the SBP and NSLP by category for up to six school years. These data enabled us to conduct a limited analysis of the boundary information, to compare school-level data with CCD data for the same school, and to compare school-level data with ACS estimates to evaluate systematic differences and precision. We also used the case study data as part of our evaluation of the relationship between eligibility and participation as the basis for claiming percentages for reimbursement under the AEO and to illustrate how the AEO might work in practice. Appendix E, Part 1 describes the data collected from the case study districts and provides summary information. In addition to providing data and collaborating with the panel, the school food authority directors of the case study school districts were invited to participate in a workshop held in Washington, DC, in March 2011. The agenda for the workshop is provided in Appendix E, Part 2.

____________

8 The Chatham County School District is named Savannah-Chatham County Public School System on its public website.

CONSTRUCTION OF EVALUATION DATABASES

The school district-level evaluation database used by the panel consists of school district-level ACS direct estimates and ACS model-based estimates that the Census Bureau provided to us, together with district-level data we obtained from the CCD and form FNS-742.9 The database includes all 13,527 school districts with both ACS 5-year estimates and ACS model-based estimates. Merging ACS estimates with the CCD data was straightforward because the Census Bureau used the NCES ID to identify school districts. However, not all school districts are included in the Census Bureau’s Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing (TIGER) files.10 Additionally, 41 districts had ACS direct estimates but were not in the CCD, and 227 districts had ACS model-based estimates but no 5-year ACS estimates.11 Merging with form FNS-742 data was more challenging because the ID numbers in that file vary by state and over time and are often different from NCES IDs. A recent study documenting the linkage between the FNS-742 and CCD districts in the country was helpful to the panel.12

The final school district-level evaluation database includes enrollment and eligibility percentages and their standard errors from ACS direct 5-year estimates (2005-2009), together with five 1-year model-based ACS estimates for calendar years 2005 through 2009 for each school district in the database. For districts with populations greater than 20,000, the database also includes three ACS direct 3-year estimates (2005-2007, 2006-2008, and 2007-2009), and for districts with populations greater than 65,000, it includes five ACS direct 1-year estimates (for 2005 through 2009). Included as well, when database records could be linked, are FNS-742 annual data for school years 2004-2005 through 2009-2010, including Provision 2 or 3 participation (not in a base year) indicators, enrollment, and percentages certified by category, along with information on categorical

____________

9 The data set is named District Data School Meals.xlsx.

10 TIGER is the database that associates codes for school districts and other political and statistical geographic areas with street segments and address ranges.

11 The Census Bureau withheld ACS estimates for some districts—probably small districts— because of disclosure concerns. Estimates were not withheld for any other reason (e.g., inade quate precision). No ACS model-based estimates were withheld.

12VSR-CCD Linkfile, a report delivered to FNS by Mathematica Policy Research on May 21, 2010, was provided to the panel by FNS. (VSR stands for Verification Summary Report.) The project director was Nancy Cole. The report notes reasons for differences between VSR (from the FNS-742) and CCD data. Although usually there was a one-to-one match, the primary exceptions occurred when school food authority (SFA) operations were centralized for mul tiple school districts. Examples where this was common include Montana, New Hampshire, and New York City. In 2008-2009, there were 14,717 (unduplicated) SFAs in the VSR file, and 95.5 percent of these matched with the CCD data.

eligibility and verification outcomes. The database includes the following CCD data for each school district for each school year from 2004-2005 through 2009-2010: enrollment; percentages certified by category; demographic information, such as the racial/ethnic distribution of students; the prevalence of English-language learners; enrollment in the district’s magnet and charter schools; and several measures of a district’s proximity to charter schools that are independent of the district. The school district database is available from a Committee on National Statistics website (http://sites.nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/CNSTAT/Using_ACS_for_School_Meals/index.htm).

The panel created the school-level evaluation database13 by merging the ACS 5-year estimates for 2005-2009 and five 1-year ACS model-based estimates (for calendar years 2005 through 2009) with the school-level data provided by the case study districts for school years 2003-2004 through 2008-2009 and with the CCD school-level data for 2004-2005 through 2008-2009. This analysis file includes only those schools in the case study districts that had school attendance boundaries in 2009-2010 (the date of the boundary file), passed the Census Bureau’s disclosure review, and were in operation during at least 2008-2009, the last year for which data were collected from the case study districts. An alternative data file14 was prepared that contained the school-level data provided by the case study districts for the schools for which no ACS data were provided (including schools without boundaries, schools that closed prior to 2008-2009, and schools withheld by the Census Bureau because of disclosure concerns). This last file also includes CCD school-level data for the same years.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION FOR DESIGNING AND IMPLEMENTING AN ACS ELIGIBILITY OPTION

The panel used three sources to gather information about the challenges associated with managing the school meals programs and attitudes regarding special provisions. These sources helped us develop details of the AEO. The three sources were a workshop with selected school food authority directors, a survey of Provision 2 and 3 school districts, and a wealth of information from the school food authority directors of the case study districts.

____________

13 Data set named District_ACS_SAIPE_CCD_schools_Master.V2.xlsx.

14 Data set named District_CCD_schools_05252011.xlsx.

Workshop

On March 3-4, 2011, the panel hosted a workshop in Washington, DC, with school food authority directors from the case study districts and with selected other individuals from the school food community who had insights to offer regarding Provision 2 and the school meals programs more generally. The purpose of the workshop was to help us better understand issues pertaining to a potential new provision for the school meals programs and the information school districts would need to determine whether to adopt this special provision. The workshop agenda appears in Appendix E, Part 2. Key observations from workshop participants follow. Note that although the workshop participants were highly knowledgeable about the school meals programs, their observations reflected their personal opinions and individual experiences rather than a consensus of the group. Moreover, their observations may not be representative of those that would be expressed by other school food authority directors.

The district representatives said they are keenly interested in increasing participation in the school meals programs, and one way to do so is to offer free meals to all students. Participation in the programs in elementary schools is already high, so the greatest potential for increased participation is in middle and high schools. To increase participation, a district must improve the image of school meals. Universal feeding likely reduces stigma, contributing to increased participation.

Several participants said there are economies of scale in offering meals and that a district can usually handle increased participation up to some point with the same seating capacity, staff, and equipment. Up to that point, there is an increase in the total cost of providing meals, but the average cost per meal goes down because the only increase in cost is for extra food. After that point, however, other costs may increase (the district may need more labor, expanded facilities, etc.).

Some districts provide universal free feeding without operating under Provision 1, 2, or 3. Typically, they do so to increase participation. The Chatham County and Denver school districts have implemented universal free feeding in some schools. Chatham’s implementation of free breakfasts in high schools reportedly increased participation. Denver instituted universal free feeding on November 1, 2010. The executive director of enterprise management for the Denver public schools stated that participation by students paying full price has risen by 6 to 9 percent, and participation by those certified for free meals has risen by 10 to 12 percent; however, participation by students certified for reduced-price meals has risen by only 1 or 2 percent.

Workshop participants agreed that having 75 percent of enrolled students certified for free or reduced-price meals is a reasonable estimate for

the break-even point15 for Provision 2 (although at least one person suggested that this figure might be a little higher—80 percent). At or above that level, the additional costs of feeding all students for free are expected to be offset by savings associated with elimination of administrative processes associated with the traditional school meals programs. Below that level, it becomes more challenging to offset the additional costs of providing universal free meals.

Workshop participants noted that the panel would have to be careful in describing differences between ACS and administrative estimates to ensure that these differences would not be interpreted as indicative of widespread fraud in the application process. They also advised that the panel would need to provide a clear and convincing discussion of the accuracy of ACS data if it were to suggest that these data would be used in the AEO. Another issue raised was whether ACS data would be deemed accurate enough for use as a replacement for the data on free or reduced-price certification percentages that are used by districts for allocating Title I funding to schools and in administering other programs.

Further, participants noted that the panel would need to address whether the ACS includes certain populations, such as migrant workers, refugees, the homeless and runaways, and military families. Pajaro Valley, for example, has a large migrant population that resides in the district only from May through October. Some of the migrant children are likely to live in migrant camps that are not included in the ACS household population. The director expressed concern about how well the ACS captures these children if the migrant population is afraid of the census and does not participate in the ACS.16

Participants were concerned about the time frame of the ACS data and about being locked into percentages that do not reflect current circumstances. They raised questions about the quality of income data reported in the ACS and how well the ACS can account for changes over time and in geography. Economic conditions can change rapidly, and attendance areas can change when there is a shift in population or a district opens new schools or closes old ones. Traditional application and certification procedures can easily capture these changes.

Participants stressed that anything that impacts funding should be

____________

15 The term “break-even point” may not be entirely accurate. The panel was unable to find any evidence that a cost-benefit analysis was used to determine this point, and in fact had difficulty in collecting consistent information about the costs of the administrative processes that are eliminated under Provisions 2 and 3, the AEO, and the Community Eligibility Option.

16 Refugees are usually settled in regular housing, where they would be captured by the ACS during the time they are in the district. However, some might choose not to participate in the ACS. The ACS includes all military personnel in the United States and their families, whether living on or off base.

effective at the beginning of a school year. Most school district budgets are developed in winter/spring (December-February) for the following school year. Reimbursement rates are available from FNS in July. Participants said they need to know the claiming percentages at the latest by July but would like to have them sooner.

Census Bureau staff participating in the workshop noted that school meals program eligibility estimates from the ACS for a particular calendar year or period (e.g., 2010, 2008-2010, or 2006-2010) could be made available within a little more than a year after the end of data collection (i.e., early 2012 for the years listed). They noted further that the school district-level data products they regularly prepare from the ACS for NCES are delivered in February-March, so most likely that would be the timing for ACS-based AEO tabulations as well.

Despite their concerns about having estimates that reflect current conditions, participants agreed that substantial variation in claiming percentages over time would be a problem for administering the school meals programs. They would prefer less variation even if the data were older and less responsive to change. Moreover, if the average reimbursement implied by the claiming percentages were to decrease because of improved economic conditions or other reasons, they would prefer steady, smaller decreases rather than a constant average reimbursement followed by a significant drop (as under the current Provision 2 when a new baseline must be established). Participants said that school districts would decide whether to adopt the AEO by “doing the math.” Districts would first determine whether the AEO might increase participation in targeted schools of interest to them. They would then evaluate the data to determine the impact on their budgets and whether they could afford the likely increased participation. This evaluation would include determining whether state requirements could be met and whether the district could accommodate increases in participation. Districts would need to make sure that à la carte food offerings or catering would provide enough money to pay any difference not covered by administrative cost savings. The concern of any district would be, “Would I lose money?” Some districts would initially consider the AEO for breakfast only.

Districts would want to have estimates of percentages eligible by category and estimated claiming percentages (if different from percentages eligible). They would need percentages eligible to report to the state—for example, for Title I. They would also need these numbers to convince themselves that the quality of the estimates was acceptable. They would need the claiming percentages (if different) to assess changes in revenue. One participant suggested that FNS implement the AEO as a demonstration or pilot program.

Participants stated that the panel’s presentation on geography and the

issues raised on the subject were outside their technical capabilities. The Census Bureau already has boundary information for all school districts, so if a district wanted to participate in the AEO districtwide, geographic boundaries would not be an issue. If districts wanted to participate in the AEO for some but not all of their schools but had to pay to have school attendance boundaries prepared, it would be very difficult for them to participate. Some workshop participants already knew where (in the local government) to obtain geographic boundaries for schools, while others had no idea how to begin looking. Representatives of participating districts expressed interest in a web application, believing that they might be able to have a staff person use it.17 (See the discussion of the School Attendance Boundary Information System [SABINS] later in this chapter.) In summary, obtaining geographic boundaries for groups of schools might be a challenge for some districts, but not all.

Survey of Provision 2 and 3 Districts

The panel conducted a survey of school food authority directors in school districts that reported operating under Provision 2 or 3. The purpose was to ascertain the advantages and disadvantages of these provisions from their point of view and to see whether they had data they were willing to share that would help us identify changes in participation because of providing universal free meals. Details concerning the frame construction, pilot test, and survey are provided in Appendix E, Part 3.

This survey was a “target of opportunity” and cannot be viewed as representative of all school districts that operate under Provision 2 or 3. However, observations made by multiple respondents are likely to be commonly held views. The panel was fortunate to have the cooperation of SNA for our study. In addition to providing a letter of support for our initial recruitment of case study districts, SNA supported this survey and provided a database entitled SNA.Provision123.data, an extract of names of participants from its recent conferences who reported that their districts participate in Provision 1, 2, or 3. The panel used this database as the sample frame for the pilot test. The pilot test involved conducting telephone interviews with 10 of 12 school food authority directors selected from the SNA list. After being refined in accordance with results of the pilot test, the survey was administered via Survey Monkey on the Internet. The

____________

17 The School Attendance Boundary Information System (SABINS) project has been working to develop a web-based digitizing application. As of April 2012, the application was still in testing. SABINS is now funded by NCES, which will host the final version of the remote digitizing service. NCES also plans to update SABINS annually and gradually increase its geographic coverage.

sample frame for the main survey was based on the FNS-742 data, which yielded 287 districts with enrollments of at least 500 that reported operating under Provision 2 or 3 (not in a base year) during 1 to 4 of the past 5 years.18 Working with its regional offices, FNS provided e-mail addresses for 100 of these districts, each of which was invited to participate in our survey; 22 districts completed the Internet survey.

Of the 10 districts participating in the pilot survey, 1 had not implemented a special provision and was out of scope, 3 were using Provision 2 for breakfast only, and 6 were using Provision 2 for both lunch and breakfast; none was using Provision 3. The number of schools in these districts ranged from 10 to 140, with an average of 41. Enrollment ranged from 5,400 to 89,000, with an average of 30,000. Of the 22 Internet survey respondents, 1 had not implemented a special provision and was out of scope; 1 reported that it had used Provision 2 in the past but could no longer afford to participate because of district finances; 1 reported that it used Provision 2 for breakfast only; and the others reported that they used Provision 2 or 3 for both breakfast and lunch. (Three stated that they used Provision 3, and 1 that it used both Provision 2 and 3. However, none of the districts reported the number of schools using Provision 3, so it is possible they did not understand the distinction or were no longer using a special provision.) Eleven indicated that they had implemented Provision 2 districtwide. About 10 districts said they had data demonstrating changes in participation due to the implementation of Provision 2, and about half of them provided those data to the panel. The number of schools in the 22 districts ranged from 2 to 90, with an average of about 16. Enrollment ranged from 1,100 to 49,000, with an average of about 8,300.

Respondents indicated that the percentage of students certified for free and reduced-price meals that triggered the adoption of Provision 2 was high. One district used the severe need breakfast cut-off (60 percent), another used 70 percent, and others used 75 percent or more. The provisions were applied most commonly in elementary schools and special high schools (where one motivation appears to be to avoid handling cash). One district respondent mentioned the geographic proximity of the schools considered for Provision 2, while another noted political ramifications if not all schools participated.

A wide range of advantages and disadvantages of Provision 2 were identified. Respondents noted the following advantages, but no respondent mentioned all of them: faster serving lines, less paperwork and labor, no applications, good for students (less stigma), no money handling, participation increases, students no longer need ID cards or money, no dun-

____________

18 We wanted to identify districts that had conducted a recent base year in hopes of obtaining base-year data.

ning of parents whose children cannot pay, and ability to serve breakfast in the classroom. Districts using Provision 2 for only some schools still had to carry out administrative processes associated with applications for the remaining schools, so the reduction in paperwork and labor was less than for districts using Provision 2 districtwide.

Disadvantages cited included the following (although some respondents said there were no disadvantages): revenue decreases, a large amount of base-year record keeping, administrative glitches requiring attention (students changing schools), and claiming percentages being fixed at the base-year level and not reflecting changes in participation or demography. There were also comments about problems in obtaining completed applications in nonprovision schools and the resulting difficulty of collecting meal charges from parents who had not filed applications but whose children ate the meals.

Districts do occasionally take schools off of Provision 2. Reasons given included the free or reduced-price percentage falling below a threshold, school closings and relocation of students, and district finances.

Most respondents said they believe they have lowered their administrative costs by operating under a special provision. However, few districts had quantified their administrative savings. Although they could cite reduced labor hours, most districts did not appear to have gained significant savings. Breakfast-only implementation appears to have more to do with hunger prevention and nutrition goals than with administrative efficiencies.

Other uses cited for the data on student certification varied considerably. Common uses included aggregate reporting needed for Title I funding under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as amended, and individual data used as socioeconomic indicators linked to test scores for reporting under the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) Other respondents mentioned grants or district needs for the data for waiving or reducing various student fees. Programs that used the aggregate numbers were cited more frequently than those that used individual family status; in the latter case, the need appeared to be mainly for obtaining fee waivers. Some respondents reported use of a separate family application process to secure Erate funding.19

District directors noted that state agencies did not appear to be proactive in promoting implementation of the special provisions or in offering

____________

19 The Schools and Libraries Program of the Universal Service Fund, commonly known as “E-Rate,” is administered by the Universal Service Administrative Company under the direction of the Federal Communications Commission, and provides discounts to assist most schools and libraries in the United States in obtaining affordable telecommunications and Internet access. See http://www.universalservice.org/sl/about/overview-program.aspx.

technical assistance. They suggested that the panel consider recommending that FNS and states provide sufficient technical assistance should the panel recommend implementing a new provision.

Additional Information from Case Study Districts

In addition to providing the information formally requested of the case study districts and participating in the panel’s workshop, the case study school food authority directors responded to many additional questions we posed as we attempted to understand the data on and processes of the school meals programs. We are grateful for their assistance. They provided input concerning the percentage of applications received by October of each year (about 90 percent, but sometimes less if the region has an economic downturn, a factory closing, or many migrant workers). Pajaro Valley provided some detail about its large number of migrant students. Omaha, an open enrollment district, provided spreadsheets showing counts of students and free and reduced-price percentages by both school catchment area residence and school attended so we could consider the impact of open enrollment. Case study directors helped us work through complexities in the data and provided examples illustrating potential causes: for example, students assigned to a school sometimes attend a different school for part of the day and receive lunch there; some districts provide school meals for children of students (not included in enrollment counts); and some districts provide Head Start programs that may move to different schools in different years.

FRAMEWORK FOR EVALUATING THE USE OF ESTIMATES BASED ON ACS DATA

This section considers the suitability of estimates for the school meals programs under an AEO from the perspective of their fitness for use. The panel applied four main criteria in evaluating the use of ACS data in support of the school meals programs:

- conceptual fit,

- accuracy (systematic differences and precision),

- temporal stability, and

- timeliness.

Conceptual fit addresses possible discrepancies between the concepts behind estimated claiming percentages and those behind the authorizing legislation and regulations of the school meals programs. In particular, conceptual fit relates to how well ACS variables can be used to define stu-

dents eligible for free or reduced-price school meals. Accuracy (systematic differences and precision) was addressed by comparing ACS estimates with administrative data20 to determine whether systematic differences exist and whether and in what situations the error from using the ACS is comparable to that associated with existing practices and provisions. Temporal stability and timeliness also were addressed by comparing ACS estimates with administrative data to assess whether ACS estimates would be sufficiently stable while maintaining adequate responsiveness to changes in socioeconomic conditions. These comparisons considered how the estimates would be used in practice and what the context of the decision processes affected by the estimates would be.

In applying this framework, the panel recognized that no system for determining claiming percentages for reimbursement for school meals is perfect. We sought to identify the best method possible, not only from an error perspective but also from the viewpoint of reducing the costs and burden associated with administering the school meals programs, as well as improving access to the programs by the nation’s schoolchildren.

The quality of an estimate has many determinants, including the data sources used as inputs and the underlying methods used to generate the estimate. Survey estimates, for example, are subject to errors that arise in the process of sampling a population, obtaining data from the sampled households, and processing the collected data to create a data set for analysis. Errors in administrative databases used for model-based estimation arise from the fact that these databases generally were not created to be analyzed as a whole, but to manage individual cases. Attention has seldom been given to editing administrative data in a unified way, so there may be data entry or other errors. A survey or administrative database will record information on variables to measure concepts that are developed for specific applications, and these variables may not match the programmatic intent of the school meals programs. Another part of the process involves identifying which records in a database are associated with the school district or school based on some geographic domain, and error can occur here as well. Finally, when estimates for small populations, such as small school districts or individual schools, are needed, the estimation method almost certainly involves some form of statistical model that specifies a structure to approximate—with error— the observed relationships in the population.

While this list of error sources may appear extensive, the current procedures for certification and meal counting in the school meals programs are subject to their own errors associated with administrative processes that

____________

20 While the panel compared ACS data with administrative data, it should be noted that the administrative data also are subject to error.

involve parents, students, lunch room staff, and office staff. As described in Chapter 2, the Access, Participation, Eligibility, and Certification (APEC) Study (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service, 2007b) showed that the error rates and costs associated with these processes can be large.

APPROACH TO DEVELOPING ACS ESTIMATES

Before estimates can be evaluated, they must first be developed. Hence, the first task facing the panel was to decide how to use the ACS to provide estimates of percentages of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals under the school meals programs. This task had two distinct activities: defining geographic regions for which estimates are needed and considering the combination of ACS variables that best identifies students eligible for school meals. This work led to the panel’s conclusions concerning ACS definitional issues and resulted in the specifications we provided to the U.S. Census Bureau (see Appendix D). This section describes the development of specifications; the next section describes our approach to evaluating the direct and model-based ACS estimates.

Developing Specifications for Geographic Areas

For the ACS and other surveys conducted by the Census Bureau, the corresponding geographic support is provided by the Census Bureau’s TIGER database, a digital map of streets, boundaries, and other features. The accuracy of TIGER was recently substantially improved through a major initiative in preparation for the 2010 decennial census, so that positional errors are now in the 5 meter range for streets and other major features. Geographic areas that are available in TIGER include blocks, block groups, census tracts, school districts, small cities, towns, counties, and states. The Census Bureau routinely provides detailed demographic data for school districts, as well as for higher levels of geography.

The Census Bureau’s SAIPE program manages the School District Review Program, which was completed most recently in 2010, to keep the geographic boundaries of school districts up to date. During the update, the Census Bureau works with states to provide updates for the school districts within the state. The next update will be completed in 2012. This state-level approach relies on collaboration between the state and local school districts to keep track of boundary changes made at the local level. The panel found, however, that local school district boundary changes occasionally are not recorded in TIGER. For example, in Pajaro Valley Unified School District in California, one of our case study school districts,

the TIGER district boundary was different from the actual current school district boundary, leading to inevitable differences in demographic data.

To obtain the estimates for school attendance areas needed for this study, the panel had to obtain digitized school attendance area boundaries from the case study districts. We were fortunate to be able to work with the SABINS project (National Science Foundation, 2009), an effort led by principal investigator Salvatore Saporito that received funding from the National Science Foundation in 2009. The project has established a spatial database of school attendance boundaries for the most populous school districts in the country. SABINS data are distributed via the National Historic Geographic Information System website, see http://www.nhgis.org/. The boundaries provided through SABINS are compatible with the TIGER database to facilitate social science research. As of early 2012, SABINS provided school attendance boundaries for the 600 largest U.S. school districts, all districts embedded in three states (Delaware, Minnesota, and Oregon), and all districts embedded in 11 metropolitan areas.

The panel received digitized boundaries from our case study districts, and SABINS independently obtained boundary information for these districts. For each district, SABINS used the boundary information to construct a database for each grade (K-12), integrated with information from the CCD, and uniquely identified the census blocks associated with each school attendance area. SABINS provided the databases for the case study districts to the Census Bureau on behalf of the panel. The Census Bureau produced estimates for these school attendance areas by aggregating block-level data associated with each school attendance area.

SABINS encountered several challenges in the collection of school attendance boundaries. Some districts maintain detailed, accurate boundaries for all schools and all grades in digitized form in geographic information systems (GIS). In these cases, the acquisition of boundaries by SABINS was straightforward. In other cases, however, there appeared to be a lack of coordination among different district agencies—for example, the version of the school attendance boundaries used by the transportation office might differ substantially from that used by other offices. In other cases, maps might exist only in rough form on paper.

The panel considered several approaches by which school districts could transfer information on school attendance area boundaries to the Census Bureau as part of the AEO, with a view to determining which approach would be most accurate, easiest for school districts, and most efficient for the Bureau to use in tabulating data for schools. We determined that the best approach would be block rectification, the method adopted by SABINS. The process of block rectification assigns each census block entirely to a school attendance area (or not). In other words, blocks are not split between two (or more) school attendance areas. This opera-

tion is easily performed in a GIS. The Census Bureau agreed that block rectification is also the most efficient approach for it to use.

In the panel’s interim report, we discussed efforts we might undertake should there be a need to split blocks (National Research Council, 2010). If a boundary splits a block, an error is associated with assigning the block to just one school, since the portion of the block not contained within that school’s attendance area will be incorrectly assigned to it. Alternatively, one might attempt to estimate the proportion of a split block’s students that should be assigned to each of the schools whose boundaries split the block. For example, one might estimate that 30 percent of the block’s students are in one attendance area and 70 percent in another. Such estimation processes are known as areal interpolation (Goodchild and Lam, 1980). Saporito and Sohoni (2006, 2007) collected maps for the schools in the 21 largest school districts and computed estimates for race and ethnicity (available at the block level) and for income eligibility for free and reduced-price school meals (available only at the block group level) from the 2000 census. They observed that “unlike blocks, block groups do not nest neatly within school attendance boundaries but, in fact, cut across them in unpredictable ways” (Saporito and Sohoni, 2007:1,231-1,232). They used areal interpolation of block group data to school attendance areas and found that “the correlation between estimated and actual percent of white children in school attendance boundaries was .999 based upon all attendance boundaries in the study” (Saporito and Sohoni, 2007:1,247).

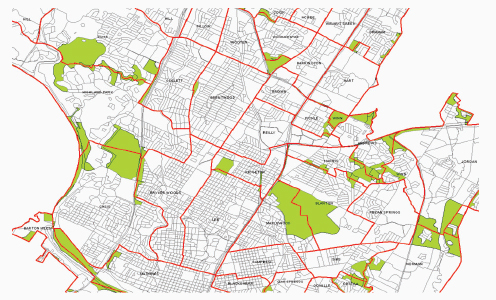

The Austin Independent School District provides a convenient example with which to illustrate the errors associated with block rectification and obtain quantitative estimates of their magnitude. Figure 3-1 shows elementary school attendance areas overlaid on 2010 census block boundaries; census blocks that straddle boundaries are shaded green. Figure 3-2 shows split blocks overlaid on an aerial image; the large split block in the lower center is composed largely of an airport. We found that split blocks often are unpopulated, an observation that is consistent with the first of these figures, where split blocks lack the dense street patterns characteristic of populated areas.

To obtain a quantitative estimate of block rectification error, we examined a random sample of 35 of the 678 Austin blocks that are split by elementary school boundaries. Of the 35, 20 have zero population. Thus, an estimated upper bound on the rectification error can be computed by taking the fraction of blocks that are split times the fraction that have nonzero population, that is, (678/9,724) * (15/35) or 3.0 percent. From this analysis, it appears that at most 3.0 percent of the elementary school population of Austin may live in a block that is split by an elementary school boundary. Only a subset of these children would be misassigned as

FIGURE 3-1 Illustration of split blocks: School attendance areas and census blocks in Austin, Texas.

NOTE: School attendance boundaries are shown in red; split blocks are shaded green.

SOURCE: Prepared by the panel.

FIGURE 3-2 Illustration of split blocks: Aerial view of school attendance areas in Austin, Texas; close-up of areas surrounding airport.

NOTE: School attendance boundaries are shown in red.

SOURCE: Prepared by the panel.

a result of block rectification. We caution, however, against generalizing too broadly from this simple analysis of one school district.

The SABINS project provides block-rectified lists for the school attendance areas in many of the country’s districts for school year 2009-2010. If available for a district, these are sufficiently accurate for use in the school meals programs and would be an easy way for a district to obtain the needed geographic data. The Minnesota Population Center has received support from the National Science Foundation to maintain the SABINS data, and some work is continuing. In early 2012, the panel learned that the SABINS project will be taken over by NCES and ultimately expanded. One of the potential issues associated with using SABINS is that it includes boundary information associated with grades K-12. If a district needs boundary information for prekindergarten grades and they differ from those associated with other grades, these boundaries will not be available from SABINS. SABINS did include most prekindergarten grades in support of this study.

Using the ACS to Determine Eligibility for School Meals

When conducting a survey, one generally is interested in collecting data on a specific concept, even if one cannot always directly observe that concept. Specification error arises when the question or measurement method does not match the target concept. For this study, the panel interpreted specification error somewhat differently: we looked at specific questions in the ACS with respect to the concepts associated with school meals eligibility criteria (e.g., income and reporting unit) compared with the original target concept the survey question was designed to measure. Another example of specification error in our application pertains to the timing of the data. For example, the ACS collects public school enrollment data for the last 3 months and income for the last 12 months from the date the questionnaire is completed, while school meals administrative data are typically dated October 31 of the school year.

A concept related to specification error is measurement error, which arises in the response process. There are many potential sources of measurement error, depending on the type of question. For example, a respondent may have difficulty understanding or be inattentive to the correct meaning of the question; have trouble recalling past events or estimating such items as income in accordance with the questions’ definitions; or provide erroneous answers because of social desirability pressures, perceived stigma, or privacy concerns when answering sensitive questions, such as those about income and program participation.

In considering specification and measurement errors, the panel focused on variables used to estimate eligibility: income, relationships

within the household, program participation (SNAP, public assistance), school status, grade, and age. Using annual aggregate income for the U.S. population as a measure, Czajka and Denmead (2008) found that the ratio of the ACS estimate to the Current Population Survey (CPS) estimate was between .995 and 1.006 for the three lowest income quintiles (the income range of greatest interest to this study), a much narrower range than the three other major household surveys used in their comparison.21 However, the annual figure averages over monthly income fluctuations and, as noted later in this chapter, is likely to indicate as ineligible some students who would be eligible for free or reduced-price meals based on monthly income values (U.S. Census Bureau, 1998). Relative to program eligibility criteria, moreover, household relationships are not completely ascertained in the ACS, and in some situations, such as with multiple family units living in a housing unit, the identification of a household for purposes of eligibility determination may be incomplete. Although the ACS includes a question on SNAP participation during the past year, public assistance programs providing cash income are lumped into a single question, and only some of those programs confer categorical eligibility for free meals. There is also evidence that program participation is underreported in the ACS.22

A key task for the panel was to determine how data collected in the ACS can be used to reflect the eligibility criteria of the school meals programs. This task has several different issues to address: (1) how to use ACS variables to identify public school students, (2) how to apply income eligibility guidelines to determine eligibility, (3) how to define income for purposes of evaluating eligibility for school meals, (4) how to group individuals in households to define a student’s economic unit for school meals eligibility, and (5) how to identify categorically eligible students using ACS variables.

Definition of Public School Students

The ACS collects information on school attendance: whether attending within the last 3 months, public or private school, and grade (or grade range). The ACS also collects information about students’ age. Hence for

____________

21 They used the CPS as a standard because it is the official source of household income and poverty measures for the United States and provides a useful standard.

22 Czajka and Denmead (2008:170) report, “As a rule surveys underreport numbers of participants in means tested programs, so in comparing estimates of participation across surveys, more is generally better.” Of the surveys they examined, the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) had the highest number, 31.4 million people (or 11.2 percent of the population), in families receiving welfare or food stamps at any time during 2002. The ACS was second, with 24.5 million people or 8.8 percent of the population.

persons in ACS data files who reside in a given public school district or public school attendance area, the Census Bureau can identify those who are less than 20 years old, do not have a high school diploma or general educational development (GED) credential, attended public school within 3 months of the ACS interview, and are in the appropriate grade range. Given the grade range of the school, the total number of such students is an estimate of the number of enrolled students in a calendar year. Most of these variables are not thought to be subject to substantial measurement error; however, there may be specification error in the assignment of students to school years and to districts and schools.

Income Eligibility Guidelines

Income eligibility guidelines are prescribed annually by the secretary of agriculture for use in determining eligibility for free and reduced-price meals and for free milk.23 These guidelines differ by the size of the family or economic unit and whether the student lives in Alaska or Hawaii. Eligibility for free meals is based on income at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, while that for reduced-price meals is based on income between 130 and at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty guidelines. Each year the secretary of agriculture announces in the Federal Register the income eligibility guidelines to be used from July 1 of the year they are issued to June 30 of the following year.24

The panel considered two options for using the school-year guidelines with the calendar-year ACS data:

- average the two guidelines from the 2 school years that occurred during the calendar year of the ACS data (e.g., average the guidelines for the 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 school years when using the 2010 ACS data), or

- 2. use the guidelines for the school year that began in the latter half of the calendar year of the ACS data (e.g., use the guidelines for school year 2010-2011 when using the 2010 ACS data).

After deliberating, the panel chose to use the second approach. The primary reason for this decision reflects the observation that most eligibility determinations for the school meals programs are made at the start of the school year, and the income for the “current” calendar year (which is not yet over) would be the best approximation of what the household would report. While a family can submit an application for

____________

23 See http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Governance/notices/iegs/IEGs.htm.

24 See http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Governance/notices/iegs/IEGs09-10.pdf.

the school meals programs any time during the year, the school district sends letters to households of all schoolchildren before the beginning of the school year, informing them of the school meals programs and inviting them to apply. A sample of the applications that have been received by October 1 of the school year must undergo verification. Data on enrollment and certification during October are the official data reported to NCES (as of October 1) and to FNS (as of October 31). Participants in the panel’s workshop indicated that generally about 90 percent of applications are received by the end of October. Workshop participants further commented that possible reasons for later applications include downturns in the local economy that result in job losses, an influx of migrant workers, or attempts to obtain benefits for summer programs.

Definition of Income

In applying to receive benefits under the school meals programs, the “household must report current income on a free and reduced price application. Current income means income received by the household for the current month, the amount projected for the first month the application is made for or for the month prior to application. If this income is higher or lower than usual and does not fairly or accurately represent the household’s actual circumstances, the household may, in conjunction with LEA [local education agency] officials, project its annual rate of income based on the guidelines on special situations” (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service, 2011b:40). In the same document, FNS describes 14 categories that make up the income that should be reported.

The ACS collects data on the gross money income of household members aged 15 and older in the previous 12 months, so an economic unit’s income can be compared against 130 percent and 185 percent of the applicable poverty guideline to determine its income eligibility status. These data are requested in eight detailed categories.

Appendix B further documents and contrasts these two detailed ways of collecting income. The FNS and ACS income definitions appear to be very close, both specifically mentioning most of the same sources of income. A few minor differences are discussed in the appendix.

While the ACS income data are designed to represent families’ calendar-year income, they reflect income received over 2 calendar years. A household is asked to report the amount of income received by each person aged 15 or older in the last 12 months, with about one-twelfth of the sample being interviewed in each month of the calendar year. Consequently, a household interviewed in January 2010 would report income data for January 2009 through December 2009, while a household

interviewed in December 2010 would report income for December 2009 through November 2010. The Census Bureau adjusts each respondent’s reported income using a Consumer Price Index (CPI) price adjustment to reflect differences in consumer prices between the 12-month period that was covered by the respondent’s answers to the income questions and the calendar year of the interview.25 Differences in the timing of income measurement between the ACS and applications for the school meals programs, combined with challenges in determining which school year should apply to a given public school student’s record, contribute to specification error.

Another challenge in using the ACS data on benefit receipt and, more generally, income is reporting error. The ACS is no exception to the well-known phenomenon of underreporting of sources of income, including substantial underreporting of public assistance benefits by survey respondents (see Czajka and Denmead, 2008; Meyer and Sullivan, 2009). It has been hypothesized that income underreporting patterns on surveys are similar to those on applications for benefits.

Definition of Economic Unit

For the school meals programs:

Household composition for the purpose of making an eligibility determination for free and reduced priced benefits is based on economic units. An economic unit is a group of related or unrelated individuals who are not residents of an institution or boarding house but who are living as one economic unit, and who share housing and/or significant income and expenses of its members. Generally, individuals residing in the same house are an economic unit. However, more than one economic unit may reside together in the same house. Separate economic units in the same house are characterized by prorating expenses and economic independence from each other. (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service, 2011b:37)

____________