3

Ethical, Legal, and Regulatory Considerations

This chapter focuses on ethical, legal, and regulatory considerations underlying the committee’s approach to responding to the questions posed by the Department of Defense (DoD). It begins with a general discussion of those considerations and previous scholarly work concerning them and then addresses considerations regarding the source of specimens. The chapter finishes with an examination of the federal laws and regulations, DoD directives and instructions, and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and Joint Pathology Center (JPC) regulations regarding research on biospecimens and their associated data.

THE CHANGING ETHICAL, LEGAL, AND REGULATORY LANDSCAPE OF BIOREPOSITORIES

Identifying Changes, Trends, and Gaps

The scientific and technologic developments of the last 20 years in genomics and informatics have greatly increased the potential value of biorepositories for understanding diseases and developing diagnostic, prognostic, therapeutic, and preventive modalities. They have also brought about substantial changes in the ethical, legal, and regulatory landscape of tissue repositories. These changes have been propelled by increased informatics capacity and other technologies that allow for larger-scale research; the mounting commercialization of research; public anxieties about possible uses and misuses of genetic information, particularly with ever larger data-sharing networks; expanded conceptions of patients’ and research partici-

pants’ rights; and heightened concerns about legal liability on the part of organizations that hold or study human genetic material and health records (Cambon-Thomsen et al., 2007; Hoeyer, 2008).

The changes have also been driven by a series of events that have captured the attention of the public and prompted examination by various professional and government bodies. Dramatic and troubling cases tend to galvanize public attitudes, thereby altering the social and cultural context of research. Much as the notorious U.S. Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee, the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital case, the Willowbrook hepatitis study, and other such events in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s transformed approaches to research involving human subjects (Katz, 1972), recent attention to problematic uses of human biologic materials in research have altered the ethical, legal, and regulatory landscape of biorepositories. Some examples are the Havasupai tribe’s lawsuit against the Arizona Board of Regents for unapproved secondary uses of tribal members’ biologic samples (Harmon, 2010); the legal actions against Texas A&M University’s use of bloodspots from newborn screening in genetic research and the Texas Department of Health exchange of such material for money and services, all without parental knowledge or consent (Beleno v. Texas Department of Health Services1; Higgins v. Lakey2); the derivation of the HeLa cell line, a highly important research resource, from tissue clinically removed from a patient without notice to or consent from the patient for research use (Skloot, 2010), and the dispute between a researcher and his institution over ownership of a cell repository (Washington University v. Catalona3). Those cases have focused attention and debate on the adequacy of the federal regulations on humansubjects research (principally the Common Rule, at 45 CFR Part 46) to address the use of archived biospecimens, especially because—under some circumstances—research use of such specimens is not considered research on human subjects under the regulations.

One essential task for the committee has been to identify and assess the crucial changes in this landscape to make it possible to offer recommendations for JPC governance of, policies for, and practices at its repository. This section maps the challenges posed by the changing landscape, identifies important normative trends for biobanking, and examines some specific decisions facing the JPC to lay the groundwork for responding to the questions that the committee has been asked to address. The committee’s task is complicated by a lack of broad public consensus on the meaning of

___________________

1SA-09-CA-188-FB (W.S. Tex., September 17, 2009).

2SA-10-CV-990-XR (W.D. Tex., July 7, 2011).

3437 F. Supp. 2d 985 (E.D. Mo. 2006), aff’d, 490 F.3d 667 (8th Cir 2007), cert. denied, 128 S. Ct. 1122 (2008).

key terms, as well as by the changing—and sometimes conflicting—ethical, legal, and regulatory standards.

Characterizing Biorepositories and Their Norms

Different terms are used to describe collections of the type held by the JPC, including tissue repository, biorepository, and biobank. Each term has a variety of meanings and somewhat different ethical, legal, and regulatory implications (Cambon-Thomsen et al., 2007; Tutton, 2010; With et al., 2011; Wolf et al., 2012, Appendix). Consider the term tissue repository, which has been used to describe collections of human biologic specimens of the sort that were accumulated over 150 years by what is now the JPC. The term seems accurate enough in suggesting that the JPC is archiving material of potential value. But by placing emphasis on the biologic material, tissue repository fails to signal the presence of associated data in the JPC collections, such as medical records and pathology reports, or of the digital slide collection. The same could be said of the more modern term biorepository, which suggests a place to hold biologic materials and hints at their use for biomedical research.4 However, many biorepositories also include data on the persons whose specimens are in the repositories, which led in the 1990s to coinage of the term biobank, defined as “organized biological sample collections with associated personal and clinical data” (Cambon-Thomsen et al., 2007). But the latter term and the related biobanking are still not fully settled with clear and definite boundaries, though the use of the term “bank” rather than “repository” implies a place where not merely deposits but also withdrawals are regularly made. Biobanks have various designs and sizes and include national biobanks set up in a number of countries where people voluntarily place genetic samples and allow the ongoing collection of medical, occupational, and other personal data that are necessary for longitudinal study of potential associations between environmental exposures, genetic variants, and health-related outcomes (Austin et al., 2003). Finally, database and genetic database sometimes also encompass both biologic specimens and associated data; this emphasizes their potential for genomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and related molecular studies (Tutton, 2010).

In line with much of the current literature, the present report uses biorepository and repository interchangeably to refer to the organized collections of biological samples with associated personal and clinical data now held by the JPC for consultative, educational, and research purposes. Another complexity for the committee’s analysis stems from the fact that,

___________________

4For instance, the International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories (ISBER) defines a biorepository as “an entity that receives, stores, processes and/or disseminates specimens as needed” (ISBER, 2008).

unlike a modern biobank created for research purposes, the different collections under the JPC’s auspices were acquired over a long period in varied ways from military and civilian pathologists primarily in the course of clinical care, and they consist of materials that are domestic and international, contemporary and historical.

Whatever their label, collections of human biologic specimens with related data, including those held by the JPC, have been used for research and education for well over a century. Some of the collections are held by individual pathologists or academic pathology departments. Others are held by hospitals or other medical-care facilities. The JPC collections are unusual because they were started in the middle of the 19th century and have accumulated millions of specimens. Scale aside, the accumulation of specimens and associated data for consultation, education, and research is a long-established practice.

Until fairly recently, these activities continued in the United States with little scrutiny. Only in the recent past have the traditional practices of pathologists and their institutions regarding the use of stored specimens for research and educational purposes and the liberal sharing of such material with medical colleagues come under scrutiny. In 1999, when the National Bioethics Advisory Commission issued a report with recommendations on the ethical use of stored human tissue, it was reflecting a new sensitivity to the ethical, legal, and regulatory issues raised by collecting, storing, and using those specimens and associated data. A substantial literature has since arisen analyzing the ethical and legal issues raised by such collections of human material (Eiseman et al., 2003; Weir and Olick, 2004).

Even as pathologists and their institutions have begun to grapple with the implications of performing research on material from source individuals5 who have rights and interests, the rise of prospective, population-based, and research-oriented biobanks has raised questions about the feasibility of meaningful contact with sources when the scale of the biobank is large. Collections, such as the JPC’s, with data and specimens obtained from pathologists involved in clinical care, are faced with the practicability of communicating about future research uses of sources’ data and specimens when those sources typically have little to no knowledge that their specimens are stored and the specimens may have been collected long ago.

As the JPC seeks to capitalize on the research potential of its collections and to accumulate new specimens in an era of ever more sophisticated and

___________________

5The term source individual (sometimes abbreviated to source) is used in this report to refer to the individual from whom biospecimens and data were obtained. Unlike the term donor, it does not imply that the person necessarily made a decision about the storage and use of the materials; such an implication would be mistaken in the case of almost all the materials held in the JPC repository.

powerful research methods, it must confront the changing ethical, legal, and regulatory standards for biorepositories. A central issue is what sort of recontact or consent, if any, is needed from a source individual for the JPC to permit his or her specimens and data to be used in various ways, including in research. To address that question, the following section discusses the surrounding ethical and legal landscape and the current challenges posed as the standards evolve.

Traditional Ethical Principles and the Need for a Contemporary Approach

Three and a half decades have passed since the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research issued its landmark Belmont Report in response to its mandate from Congress “to identify the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research” (National Research Act, PL 93-348; July 12, 1974). During that time, the three principles that it articulated—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—have come to provide a foundational means of evaluating the ethics not only of research with human subjects but of patient care. Not surprisingly, those principles carry great weight in the present committee’s analysis of the JPC’s ethical obligations in managing and using its biorepository.

For at least five reasons, however, the committee believes that it must go beyond the original applications of the Belmont principles, especially “respect for persons.” In articulating what is meant by respect for persons the National Commission attempted to yoke together “at least two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection” (National Commission, 1978). The latter is relevant to the ethics of a biorepository constructed from specimens and related data obtained during clinical procedures inasmuch as some of the specimens will have come from patients who had diminished capacity to consent, either generally (for example, children and mentally disabled persons) or temporarily (for example, as a result of injury or disease). Some (perhaps most) of the sources whose material is contained in the JPC repository cannot now be contacted because they are deceased, so whatever their ability to exercise autonomous choice when their material was collected, that ability is now not merely “diminished” but nonexistent as to potential research with the material.

The second reason why it is not possible in the JPC context simply to apply the Belmont principle of respecting autonomous choice is that autonomy is usually regarded as requiring—for example, by the Common Rule6—“legally effective informed consent,” which involves the disclosure

___________________

6The Common Rule is addressed in greater detail later in the chapter.

of a long list of “basic” and “additional” information (45 CFR § 46.116[a] & [b]). As a historical matter, such disclosure and agreement did not accompany the gathering of the material that now resides in the JPC collections; it seems unlikely that an elaborate form of consent addressing future clinical, educational, and research uses will be obtained regarding the material routinely referred to the JPC in the future for pathologic examination. That raises the question of whether it is possible, as an ethical matter, to respect the principle of autonomy by a process of informed decision-making that differs from the consent ordinarily expected before people may be enrolled in a clinical trial.

A third reason for the apparently limited applicability of “respect for persons” to biorepositories is that specimens separated from the person have traditionally not been regarded as “persons” requiring respect. In the Moore case, the California Supreme Court refused to recognize that John Moore, whose excised tissue had been used in research without his informed consent to generate a profitable cell line, had a claim based on conversion of his property (Moore v. Regents of the University of California7). Guidance issued by the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP), which allows research without consent on de-identified samples that were not originally collected for research, continues this approach by determining that de-identified specimens are not considered “human subjects” at all (OHRP, 2008a). However, recent analyses have appealed to a broader notion of respect for persons to justify attention to the beliefs, values, and preferences of source individuals in the use of their materials in research (Trinidad, 2011). Even in the Moore case, the California Supreme Court indicated that physicians had a fiduciary duty to Moore to disclose the use of his tissue in research. The principle of respect for persons has important implications for the use of persons’ specimens in research without entailing that specimens are persons or even the property of persons.

A fourth reason to question the simple application of “respect for persons” lies in the difference between research scandals of the sort that propelled the creation of the National Commission (Beecher, 1966; Katz, 1972) and research that involves material from biorepositories. The ethical framework recommended by the National Commission was designed to protect subjects in their dyadic relationship with investigators by imposing obligations on the latter and subjecting their decisions to independent review by an institutional review board (IRB) before the start of research. However, biorepository research involves not a relatively small number of subjects who interact directly with an investigator but usually a large number of people who have no direct involvement with investigators in the context of research which may or may not be reviewed by an IRB.

___________________

7793 P. 3d 479 (Cal. 1990).

The nonclinical focus of some types of research on populations, such as studies that use the records and biologic material held in repositories, generates the fifth reason why Belmont cannot be taken as a complete statement of the relevant ethical principles for this analysis. Not only is Belmont built on the investigator–subject dyad but it focuses on protecting subjects as discrete individuals. In recent years, many ethicists have recognized the importance of thinking of research in terms of groups as well as individuals (Goldenberg et al., 2011). That does not mean simply substituting “community” for “individual autonomy” as a main guiding value but rather recognizing that some interests that need protection belong to a group rather than solely to individuals and that a means is needed to allow the welfare of the group to be represented in decisions about whether to go forward with some research.

Although issues of that sort were not in the foreground when the Belmont principles were set forth, the desire not to foreclose all research for which obtaining individual informed consent would be difficult or impossible was certainly on the minds of the authors of the federal regulations on human-subjects research, now stated in the Common Rule. Influenced in particular by large-scale studies that involved data that were either publicly accessible or anonymous or that involved the use of dead bodies or material obtained from them (as was an accepted part of hospital autopsies and medical-school education), the rule drafters either excluded from IRB oversight any research that involved such material or data or permitted institutions to waive consent requirements. That kind of research did not expose anyone to a risk of physical harm or of serious harm to other interests (given the nature of the data, such as public records or information from telephone directories), so the lack of IRB review of it did not seem problematic. Today, however, the extent and types of information that can be generated by analyzing the biologic specimens and data in biorepositories—including genetic and genomic analysis—far exceed what could have been produced when the Belmont Report was written. Thus, just as the literal application of the Belmont Report’s autonomy principle could unduly constrain the potential of biorepositories as important components in the modern system of research, reliance on the exclusions and exemptions of the Common Rule could remove such repositories from appropriate oversight.

The solution adopted by the committee was to revisit the mission that guided the National Commission and, rather than focus on the particular instantiation of the principles in the Belmont Report, to concentrate on the foundations of the principles that are “generally accepted in our cultural tradition” (National Commission, 1978). In addition, the committee carefully considered more recent statements of the ethical and legal standards that should govern biorepositories, along with evolving practices. It was

then able both to modify the particular manifestations of the Belmont principles in current use and to use the principles to develop a framework for biorepository governance, especially if they are understood more broadly and less individualistically than has sometimes been the case (Childress et al., 2006; Weir and Olick, 2004). Later sections of this chapter and the next chapter address the need to specify and balance those and other principles (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009) in the process of developing concrete recommendations for the governance, policies, and practices of the JPC biorepository.

Governance refers to organizational structures and processes of decision-making and accountability (Gottweis and Petersen, 2008; Kaye et al., 2012b). In the world of biobanks, governance often includes an organization’s policies regarding acquisition, storage, access, and the like, as well as specifying the persons or institutions that set and apply those policies. Some proponents of governance view it as a way to move beyond or provide a substitute for informed consent in light of practical and regulatory limitations on consent in large-scale contexts (Hoeyer, 2008; Prainsack and Buyx, 2011). Because an obligation to demonstrate respect for persons does not diminish even with good governance, others have proposed using consent to a process, or governance structure, to overcome problems with seeking consent at one point in time for a range of future research uses (Caulfield et al., 2008; Kaye et al., 2012a).

Proposals for biobank governance often reflect one or more guiding metaphors, mainly drawn from ownership or from stewardship, custodianship, and trusteeship (Jeffers, 2001; O’Brien, 2009; Yassin et al., 2010). The latter metaphors recognize the role of the biobank as protector of interests other than its own and stress responsibility for the materials and their uses. It is also important to recognize, where appropriate and possible, responsibility to the individual sources of biological specimens and data—sometimes called participants—even if the research does not qualify as research on human subjects under the Common Rule. Because of the historical nature of the JPC collection, it makes more sense to adopt a governance framework that captures the fiduciary obligations of the collection holders (such as stewardship over the specimens and data) rather than one that relies on active, engaged partnership with participants. However, there are ways to express the principle of respect for persons and other ethical principles even in these circumstances.

Implementing Broader and Richer Conceptions of Respect for Persons and Other Ethical Principles

U.S. and European biobank policies tend to differ in important ways regarding the use of biologic specimens and data in research. There is an in-

creasing acceptance of broad or general prior consent in European biobanks (Noiville et al., 2011). A person who gives broad or general consent does not surrender the right (within limits) to withdraw biologic materials and data later. Such consent also presupposes that an appropriate ethics committee will review the future research (Elger and Caplan, 2006; Tutton, 2010).

In the United States, in contrast, requirements for informed consent to research on biologic specimens have generally been closely connected with risks to privacy and confidentiality, considered the major risks posed by research uses of excised tissue and associated data (Elger and Caplan, 2006; Tutton, 2010). If the samples used in research are not identifiable and the risks to the sources are considered to be minor, the samples may be used without informed consent. According to that view, adequate protection of the sources’ personal identities through deidentification obviates the need for informed consent to research uses. Proponents of this approach stress that it provides adequate protection for the privacy interests of source individuals while costing the organization less.

The approach is not unproblematic. First, the definitions of and boundaries between identifiable and nonidentifiable samples are debatable. Those terms are used in varied and inconsistent ways. Moreover, as a result of scientific and technologic developments, OHRP and others have suggested that in principle all biologic specimens should be viewed as potentially identifiable (HHS, 2011; McGuire and Gibbs, 2006; Schadt et al., 2012). Third, breaches of privacy and confidentiality remain possible, however slightly, and their probabilities are magnified by research networks and wide sharing of data. It is thus important to recognize, but not exaggerate, this risk (Malin et al., 2011).

Additional arguments focus on the losses to scientific research and to sources themselves from reliance on deidentification or anonymization. If deidentification is irreversible (that is, a key code for reidentifying individuals is not retained or is not accessible), researchers cannot gain access to some information that would be useful in their research and sources cannot receive potentially valuable individual information from the research (Wolf et al., 2012). Regarding the latter, studies indicate that sources attach high value to the disclosure of potentially valuable results and incidental findings (Hoeyer, 2008). To be clear, though, it is possible to perform valuable research on deidentified data (Clayton et al., 2010).

Obtaining informed consent for biorepository research is not only a possible way to protect sources from harm but serves the purposes of manifesting respect for persons and allowing sources’ values and preferences to shape research. As this report has suggested, biorepositories can and should develop ways to respect persons who are sources of biospecimens as participants in research on archived materials even when informed consent to research uses may not be required or may be impossible (Prainsack

and Buyx, 2011). Studies suggest that sources want more control, even though they do not necessarily insist on exercising specific informed consent to particular research protocols (Hoeyer, 2008; Wendler and Emanuel, 2002). Of course, caution is required in interpreting surveys and qualitative studies of the perspectives of sources of biospecimens; responses vary for an array of reasons (Hoeyer, 2008). Nevertheless, the preferences for more participation in the research process and for being informed about research results that are particularly relevant to them appear to be widespread and strong views among people who could be the source of biospecimens,8 and new ways are being developed to enable participants to engage in the research process through the use of such tools as interactive information technologies (Kaye et al., 2012a).

Several analysts of the changing normative landscape of biorepositories contend that repositories should focus less on informed consent alone and more on becoming institutions that can generate and maintain trust (O’Doherty et al., 2011). One commentator concludes that “it is time to move the debates beyond informed consent and to critically assess what can be done to make biobanks into trustworthy institutions of long-term social durability” (Hoeyer, 2008). Trust is essential for biorepositories (Dabrock et al., 2010; Hansson, 2009; Hawkins and O’Doherty, 2010; Manson and O’Neill, 2007; O’Neill, 2002) because they depend on voluntary participation and without trust cannot succeed. In seeking to generate and maintain trust, it is crucial for biorepositories to develop and display trustworthiness through their governance, policies, and practices (Yarborough et al., 2009). Those points have long been recognized with respect to organ transplantation: the public’s trust in the process of organ donation and allocation is crucial to its willingness to donate organs.

Studies of industries that have lost public trust and worked to regain it have identified proactive attention to relationships (engagement and communication) and accountability as essential in building trustworthy practices (Yarborough et al., 2009). Other trust conditions often include faithfulness in keeping promises, meeting legitimate explicit or implicit expectations, and truthfulness (Hoeyer, 2008; Prainsack and Buyx, 2011). Transparency also appears on most lists of conditions (O’Doherty et al., 2011). However, some commentators worry that transparency will actually reduce trust (Cambon-Thomsen et al., 2007). When biorepositories’ policies and practices are publicly justifiable, transparency can help to generate and maintain trust. Justification should be preceded by engagement with the relevant stakeholders. Exactly what kind of engagement and with whom is both desirable and feasible can be debated and depends upon many factors.

___________________

8Hoeyer (2008) has summarized the empirical research, and others have also addressed the topic (Chen et al., 2005; Trinidad et al., 2011; Wendler and Emanuel, 2002).

The materials in the JPC repository were collected largely from military personnel and their families, with some additional materials from difficult civilian cases submitted for consultation. The JPC may be able to engage military personnel and their families in ways that can inform its governance. Such engagement may increase the likelihood that its policies and practices will be consistent with the values of that community, address group concerns, and reduce the risk of harm to the group and its members (McCarty et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2011). Practices vary widely, depending on the needs of the repository and the community it is serving, from community representatives on data-access committees participating in every data-release decision to community advisory boards (CABs) that consult on policy and general directions for the repository rather than on day-to-day decisions (O’Doherty et al., 2011).

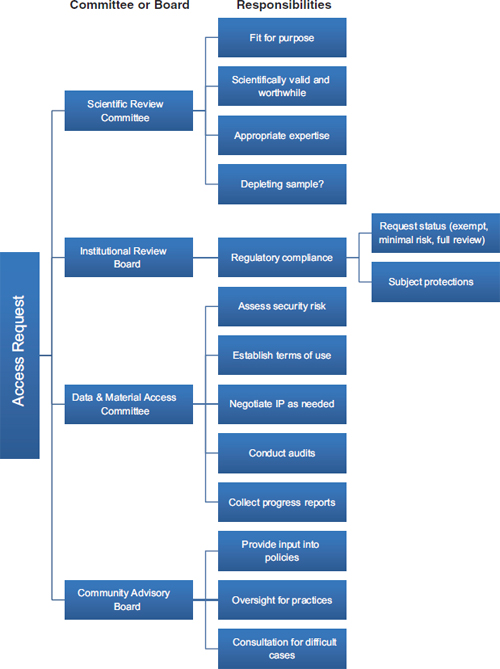

Those contemporary approaches to biobank governance also draw on the other traditional principles that guide research ethics: beneficence and justice. The principle of beneficence has generally been specified through two complementary general rules: to do no harm and to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms (National Commission, 1978). Those rules have obvious application to biorepositories in that the realization of their potential benefits for scientific and technologic progress is more likely if their governance is responsive and adaptive. Specifically, the principle of beneficence requires minimizing harms, costs, and other burdens on research participants and balancing any that remain against the potential benefits of the research. Governance mechanisms, such as data-access committees and CABs, and traditional oversight mechanisms, such as IRBs, can go a long way toward assessing whether a proposed use of specimens in the collection will minimize harm and maximize benefits. Input from the specimen sources can, for example, help ensure that the evaluation of benefit expresses the perspectives of the source population as much as possible, rather than merely reflecting scientific perspectives. Figure 3-1 provides an example of a governance mechanism that uses a scientific review committee, a committee on data and material access, a CAB, and an IRB.

The third principle articulated in Belmont (along with respect for persons and beneficence)—justice or fairness in the distribution of the benefits and burdens of research—likewise has several implications for biorepository governance. An obvious one concerns fair access to biologic specimens and data for research, education, and consultation, especially in the case of rare and unique materials. This is an important issue for the JPC’s governance. The taxpayer funding of the repository appears to support the broadest possible access subject to appropriate priorities and limits. Reasonable priority setting could, for example, include meeting the needs of the military and of military personnel and veterans first; defensible limits could include protection of national security. Ensuring the sustainability of the collections

FIGURE 3-1 A biorepository governance mechanism that uses a scientific review committee, an institutional review board, a data and material access committee, and a community advisory board.

NOTE: IP = intellectual property.

may also affect the extent to which rare and unique biospecimens may be distributed and the costs passed on to users of the materials for research, education, and consultation. And it will be important to ensure that no one group of specimen sources bears undue burden or risk of exposure.

Another sense of justice has become important over the years: participatory justice. Justice in this sense encompasses fair participation in the biorepository’s process of setting policies and priorities, for instance, regarding uses of biologic specimens and data. Fair participation is particularly important in the partnership model of biorepository governance, but it is also relevant to models of custodianship, trusteeship, or stewardship. It is not easy to specify fair participation in terms of the stakeholders to be included or the mode of participation to be extended. Nevertheless, such participation is important not only as a matter of justice but also because of its potential contribution to trust in the biorepository.

Conflicts Within and Between Ethics, Law, and Regulations

Ethics, law, and regulation both overlap and conflict in the normative guidance that they offer for biorepositories. Law and regulation often embody ethical considerations and set minimum standards of ethical conduct. However, there are diverse views about the relevant ethical norms (Capron et al., 2009; Häyry et al., 2007), and some ethical norms go beyond or even contradict operative laws and regulations. At other times, laws or regulations may set a higher standard than current ethical norms require. In either case, there can be what commentators have termed a “growing gulf” with regard to research using human biologic materials and associated data between the current legal and regulatory frameworks and practice, on the one hand, and ethical and cultural perspectives and participant preferences, on the other hand (Trinidad et al., 2011).

Conflicts may also arise among particular laws and regulations, making it difficult to determine which is determinative in a particular decision or case, especially with respect to the myriad laws and regulations—federal, military, and state—that may apply to the JPC’s activities. One example—addressed later in the chapter—is the tension between the Common Rule (as interpreted by OHRP), which allows general consent for research uses of donated tissue, and HIPAA, which requires authorization by a patient for the use of his or her protected health information (PHI) in a specific research proposal (With et al., 2011). Moreover, the standards adopted by other countries and by international organizations become relevant and important when research crosses national boundaries.

The remainder of this chapter will examine several issues raised by the JPC’s new structure and mission in light of the above and other ethical, legal, and regulatory frameworks and principles. Most of the questions

posed to the committee center on research uses, and the text concentrates on these uses. Attention is also paid to the ethical, legal, and regulatory issues that arise when repository materials are used in clinical consultation and education because all three uses may involve purposes beyond direct benefit to the individual sources of the biospecimens and data. At the end of the chapter, the committee offers some concluding reflections on consent and custodianship of biological materials and associated data.

CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING THE SOURCE OF SPECIMENS

The DoD, noting that the JPC repository contains consultation material from both military facilities and civilian providers, asked the committee to offer comments on whether materials from civilian providers could be used in the future in the same manner as those from military facilities. This section addresses some considerations surrounding that issue. It approaches the discussion from the viewpoint of what the committee believes to be the salient distinction: whether a sample is derived from a civilian or from a current or former member of the U.S. military.

There are several reasons why military personnel might be viewed differently from civilians. They generally cannot resign their position; they are obliged to follow lawful orders, including orders that may result in their physical harm; the rules under which they agree to serve may be changed without their consent; and they may under some circumstances be recalled into service after they have left it (Weedn, 2011). With relation to health matters, they are required to be physically and mentally fit; they cannot refuse treatment, immunizations, or prophylactic drugs; and they may be compelled to provide biologic specimens (Baker personal communication, 2011; Henricks, 2004; Rushenberg, 2007). Protected health information in their records may in some circumstances be provided to “military command authorities” without their authorization or without an opportunity to object (Rushenberg, 2007). In addition, “military expediency” is recognized as a justification for waiving informed consent (Executive Order 13139; September 30, 1999).

As noted in Chapter 1, specimens in the JPC collection come from a number of sources. Clinicians in military health facilities in the United States and abroad submitted samples for clinical consultation. Diagnostic material and data from military health facilities that were shut down under the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process were transferred to the JPC to satisfy accreditation requirements for specimen retention. Registries of samples collected from military personnel who served in a particular conflict or shared a particular exposure are housed there. And pathologists from around the world who were seeking second opinions from the expert specialists at the repository provided case materials.

The answer to the question of whether different rules apply to specimens derived from the different sources—military patients, civilian patients (most often, military dependents or retirees) under the care of military physicians, and civilian patients receiving care at nonmilitary facilities around the world—depends principally on what policy is proposed regarding future use of the samples generally. If their use is limited to applications that directly benefit the patients from whom the specimens were derived (for example, a clinical consultation) or to research studies for which the patients gave explicit informed consent, there is no reason to differentiate between military-derived and civilian-derived specimens. But if uses beyond those two are contemplated, the legal and ethical reasoning in support of such broader access may require differentiating between military and civilian patients. The primary categories of future use—diagnostic uses or other uses to benefit persons other than those from whom the samples were derived and research uses beyond those explicitly agreed to by the persons from whom the samples were derived (or their legal representatives)—can be examined separately.

Two principal groups of persons could benefit from allowing medical professionals access to a patient’s stored specimen: members of the patient’s family and members of a group with whom the patient shared a life experience that was possibly relevant to his or her medical condition. For this type of use, the specimen and related medical records would, of course, need to be personally identifiable. If the patient is known to still be alive, ethical considerations suggest that a person seeking access to the specimen and any related data would provide evidence of the patient’s consent for the release. In the case of a patient known or reasonably believed to be deceased, the patient’s personal representative9 would control release whether the material came from a civilian or military source. Under certain circumstances, there may further allowance to fulfill a close relative’s legitimate medical need.

In responding to requests for access, custodians of the JPC collection would have no reason to differentiate between specimens and records of military and civilian origin. In ordinary circumstances, it may be assumed that any close relative10 would have an equal, personal right to access a stored specimen when doing so is necessary to meet a medical need that his or her physician attests cannot be met with equal ease and utility by another available means. If an objection were lodged by another relative—because, for example, the information obtained from the material held by the JPC would not be used solely to benefit the person seeking it but might

___________________

9In brief, “[t]he personal representative stands in the shoes of the individual and has the ability to act for the individual and exercise the individual’s rights” (HHS, 2003a). Rules regarding personal representatives under the HIPAA Privacy Rule are explicated in 45 CFR 164.502(g).

10Such as a parent, sibling, child, grandchild, niece, nephew, aunt, uncle, or first cousin.

be imposed on others, such as relatives who do not want it—the JPC would have to consider whether some safeguard could be found to avoid or at least minimize the potential harm and second to balance any remaining unavoidable harm against the good that disclosure would serve.

Ordinarily, in the absence of a judicial order, nonrelatives would not be entitled to have access to identifiable samples and associated data held in a pathology laboratory. Consequently, persons other than close relatives seeking access to civilian-derived material in the JPC collection would be referred to the pathology service that sent the material to the repository, and the pathology service could make its own determination, on the basis of its understanding of applicable rules and its ability, if any, to contact persons who may speak on behalf of the deceased patient.

There are good reasons for potentially taking a different view concerning access to specimens sought by persons who have a military connection with the deceased, such as having served in the same unit or same theater of operations. If the material is sought for what amounts to an epidemiologic study—an examination of specimens derived from a number of patients who shared common experiences and possible exposures, for example—it could be provided on a deidentified basis with the requirement that those receiving it make no effort to break the anonymity or to contact any persons, or relatives of those persons, whose materials have been provided. And, given the allegiance of military personnel to the men and women with whom they have served, it may be more reasonable to suppose that the armed forces members whose samples and data are held in the JPC would, if it were possible to consult them, approve the use of their samples (with appropriate protections for personal information) when they are needed by a fellow service member for diagnostic or treatment purposes. It may be appropriate to explore with service-member organizations whether the latter presumption seems reasonable and whether they would support the conclusion that deidentified samples and information should be provided when requested by a present or former service member (or a representative of such a person’s family) who has a service-related connection with the persons whose samples and information are being sought.

Potential research use of the various parts of the JPC collection raises two connected issues: first, the conversion of some of or all the parts into an accessible biobank that would be made available (under appropriate rules and procedures) to researchers and research institutions; and second, access to particular specimens, and sometimes related data, for particular research projects. The two differ in that a presumption of relatively easy access to specimens seems to accompany the creation of a biobank, whereas a case-by-case decision process admits of the possibility, but not necessarily the probability, that researchers will be able to make use of material in the JPC collection for research purposes.

There are three potentially differentiating issues for civilian-derived vs. military-derived specimens. First, it can be argued that presumed consent to research may make more sense for military-derived specimens in cases in which release might otherwise be contested, if the JPC has received approval for the research from the DoD, by analogy to the special rules for research on service members without consent.11 Second, it is possible to turn to groups of service members, veterans, and their families to act roughly as surrogates for military patients whose materials are in the collection and review proposed research uses of samples and data from the collection that raise particularly sensitive issues, whereas there is no natural surrogate group for the highly heterogeneous populations from which the civilian-derived specimens were obtained. Third, it is arguable that current and former military members and perhaps their family members would have more inherent trust in and see themselves as having an indirect relationship with a military facility, such as the JPC, whereas it is unlikely that civilian patients whose materials are held at the JPC are even aware of—or have any sense of having consented to—the presence of their materials in the JPC collection.

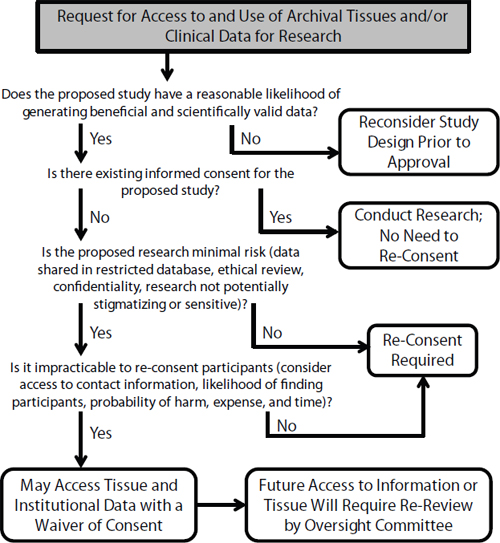

CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING RESEARCH ON DIAGNOSTIC SPECIMENS AND ASSOCIATED DATA

The committee was asked to offer advice on whether tissue collected for clinical use may be used for research, including cases in which the tissue came from patients who did not specifically consent to its use in research. As noted above, this is a complex question of law, ethics, and policy. Indeed, controversy has surrounded the question of under what circumstances clinically obtained tissue may be used for research12 and, in July 2011, the Department of Health and Human Services issued an advance notice of proposed rule making (HHS, 2011). The discussion that follows references law and guidelines that were in place when the committee completed its substantive work in the middle of 2012 but notes pending proposals that have the potential to affect the answer to the question.

___________________

11DoDI 3216.02 (Enclosure 3, § 9(c); November 8, 2011) indicates that the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering may waive the requirement for informed consent for certain types of research when all of the following are met: (1) the research is necessary to advance the development of a medical product for the military services; (2) the research may directly benefit the individual experimental subject; and (3) the research is conducted in compliance with all other applicable laws and regulations.

12Moore v. Regents of the University of California (51 Cal. 3d 120; 271 Cal. Rptr. 146; 793 P.2d 479), discussed, for example, by Skloot (2010).

Background

As detailed in the first chapter, the JPC repository holdings were collected over a period of more than 100 years at a wide range of both military and civilian facilities in the United States and abroad. Consent, if any, to use of the materials was not obtained by the repository itself but by the clinicians or clinical centers where the specimens were removed from patients. In recent years (since at least 1995, the earliest date found by the committee or the JPC), a physician or other medical professional submitting material to the repository has been required to include a signed Contributor’s Consultation Request Form. The form requests detailed information on the patient and case and notifies the contributor of the repository’s retention policy, which states that the facility generally retains slides permanently and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks for at least 10 years. The policy further states that “other pathological material, X-rays, CT scans, MRI scans, echograms, angiograms, photographs, and similar diagnostic studies may be retained for education and research or discarded” (JPC, 2011a; emphasis added). The form also mentions possible research use in a section titled “Privacy Act Statement”: “medical information received is considered during the consultative process and is used to form a database for education and research in pathology” (JPC, 2011a).

It is unclear whether patients were notified of or asked to consent to having their material sent to the repository’s staff for consultation; it is unlikely that they were notified of or asked to consent to retention of their specimens and data for future use by the repository, with the possible exception of materials gathered for some of the war or cohort registries.13 The committee was informed that the individual sources generally were not notified or asked to consent by either repository investigators or parties outside the repository (Baker personal communication, 2011).

In any case—again, with a few possible exceptions—the JPC does not have copies of any consent forms used in obtaining the material in its collection (Baker personal communication, 2011). In light of the variety of the possible consents, including no consent, the committee broadened the question before it to address whether tissue collected for clinical use may be used for research in the full array of circumstances represented in the JPC collection. That included the acceptability of research not only on tissue but on the associated material (such as X-ray images and computed tomography scans) and clinical data (such as patient information provided by the contributing physician up to and including patient medical records) and research on archived material and data in the absence of a tissue specimen.

___________________

13These registries are described in Chapter 1. Consent for future research use may have been obtained for materials gathered for the war or cohort registries, but JPC has no documentation regarding this (Baker personal communication, 2011).

Almost all tissue specimens in the repository are archived with at least some associated data.14 The Contributor’s Consultation Request Form (JPC, 2011a) asks for patient information, including name, date of birth, Social Security number, race, ethnicity, contributor’s working diagnosis, and clinical history. The form states that “pathology consultation records contain individually identifiable health information.” Although it notes that the contributor’s providing patient information on the form is voluntary, it also says that “if the information is not furnished, a consultation may not be possible.” Thus, research on specimens might include research on associated data. Furthermore, a portion of the repository’s BRAC Collection consists of only records with no associated biospecimens. Consequently, JPC repository biospecimens and associated data—and records in the absence of tissue—could all be sought for research.

As discussed below, some of the persons whose specimens and data are archived in the JPC collections may qualify as research subjects or participants, and others may not even if their tissue, material, and data are used in research. There is no consensus term for research that does not constitute research on human subjects, although Brothers and Clayton (2010) have suggested “human non-subjects research.” There is also no consensus on a term to use for the individuals from whom these materials are obtained; the literature variously calls them participants, donors, contributors, and sources (the last is the term used in this report). Most specimens and data were submitted to the repository for clinical consultation although BRAC materials are an exception in that they were simply transferred to the repository for retention and storage when the military facilities that housed them were closed, and some of the war and cohort registry materials were collected specifically for documentation or research purposes.

Veterans’ Attitudes Regarding Research Use of Biorepository Materials

A small literature exists on veterans’ opinions regarding research use of their biological material. Kaufman and colleagues (2009) surveyed veterans receiving health care through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system on their attitudes regarding the establishment and operation of a repository of genetic material and related clinical information. The biobank, VA’s Genomic Medicine Program (GMP), is to be made available for health-related research. Eighty-three percent of the participants in the study (n = 931) indicated support for the GMP and 71 percent said they

___________________

14A small number of cases in the Central Collection have only medical records because the associated slides or biomaterials were returned to the contributor or otherwise lost or destroyed (Baker personal communication, 2011).

would participate in it. Approval was consistently high in all demographic and age groupings, although black non-Hispanics and veterans who first served during or after the Gulf War were less likely to back the program. Altruistic motivation was commonly cited as a reason for support, with about 80 percent of respondents indicating that participation would make them feel like they were helping other veterans. A follow-up paper by the investigators examined veterans’ views on opt-in and opt-out enrollment options in research studies (Kaufman et al., 2012). It reported that just over three-quarters of those sampled felt it was a “good idea” to use leftover biological materials for research applications, although almost half were not aware of their materials being used in research at all. Support for both opt-in and opt-out enrollment models was found; however, more women and minorities significantly preferred the opt-in approach.

Federal Regulations Regarding Research on Biospecimens and Associated Data

A comprehensive analysis of applicable law (statutes, regulations, and governmental guidance) would consider both federal law, including any specialized military requirements, and state law.15 Two domains of law are particularly relevant here: law on research involving human beings and derived tissues, material, and data and law on protecting the privacy of individuals. The goal of the present analysis is to determine what duties and limitations the law places on the JPC’s use or dissemination of specimens, associated material and data from the repository, for research purposes when the source has not given consent beyond that needed for the collection of specimens in the course of clinical care. Further, when such use is permitted, the goal is to articulate the various considerations and conditions surrounding research use.

Generally speaking, research on biospecimens and associated data in the United States is subject to two16 primary sets of federal rules related to the protection of study subjects and their health information: those promulgated under HIPAA and the implementing regulations at 45 CFR Part 164, and the so-called Common Rule, the regulations for protection of human subjects in research adopted by federal departments and agencies that conduct and sponsor such research (including the DoD and the Department of Veterans Affairs) and administered by the OHRP in the Department of Health and

___________________

15This report does not address state statutes and regulations, which may apply to some uses of biospecimens and data but do not materially affect overall policy planning in the JPC as a federal entity.

16Human-subjects research under Food and Drug Administration (FDA) purview is subject to FDA’s rules at 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56. These are similar to but not identical with the Common Rule.

Human Services (HHS).17 This section briefly summarizes salient sections of the current rules and guidance statements. Far more detailed and complete discussions of some of these rules are available in the 2009 Institute of Medicine report Beyond the HIPAA Privacy Rule: Enhancing Privacy, Improving Health Through Research, from which much of the material in this section is excerpted or derived. Additional human-subjects research and privacy rules applied by the U.S. military are addressed in the next section.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

The primary goals of the U.S. Congress in passing HIPAA in 1996 were to make health care delivery more efficient and to increase the number of Americans with health insurance coverage. In furtherance of these goals, the statute mandated what is now known as the HIPAA Privacy Rule, which regulates the uses and disclosures of “protected health information” (PHI) that health care professionals and institutions are permitted to make. PHI is defined as “individually identifiable health information” that is held or transmitted by a “covered entity.”18 Although the HIPAA Privacy Rule applies to information uses and transactions necessary for the provision of health care, it is also applicable to a great deal of information used in health research. When obtaining PHI from a covered entity to use in their research, researchers are required to follow the Privacy Rule’s provisions. The Privacy Rule permits a covered entity to use and disclose PHI for research purposes without an individual’s authorization if the covered entity obtains either of the following (45 CFR § 164.512(1)):

- Documentation that an alteration or waiver of the individual’s authorization for the use or disclosure of the information has been approved by an IRB or privacy board.

- Specified representations from the researchers that the PHI is being used or disclosed solely for purposes preparatory to research or for research using only the PHI of decedents.

A covered entity may also use or disclose PHI without an individual’s authorization if the PHI is contained as part of a “limited dataset” from which specified direct identifiers have been removed and the researcher enters into a data-use agreement with the covered entity (45 CFR § 164.514(e)). And data may be publically shared under HIPAA’s so-called “safe harbor”

___________________

17The HHS version is at 45 CFR Part 46, and the DoD version is at 32 CFR Part 219.

18Covered entities are individuals and organizations that transmit information in electronic form in connection with a transaction for which HHS has developed a standard under HIPAA (45 CFR § 160.103). AFIP was and the JPC is a covered entity.

provisions if 18 categories of information comprising “explicit identifiers (e.g., names), ‘quasi-identifiers’ (e.g., dates, geocodes), and traceable elements (e.g., medical record numbers)” (Malin et al., 2011) are stripped from them. The categories are listed in Table 3-1.

In crafting the Privacy Rule, HHS acknowledged that it is not always possible to obtain authorization for using or disclosing PHI for research, particularly in circumstances in which thousands of records may be in-

TABLE 3-1 Individual Identifiers Under the Privacy Rule

| The following 18 identifiers of a person or of relatives, employers, or household members of a person must be removed, and the covered entity must not have actual knowledge that the information could be used alone or in combination with other information to identify the individual for the information to be considered deidentified and not protected health information. |

|

• Names |

|

• All geographic subdivisions smaller than a state, including county, city, street address, precinct, ZIP code (first 3 digits OK if geographic unit contains over 20,000 persons), and their equivalent geocodes. |

|

• All elements of dates (except year) directly related to an individual; all ages over 89 years and all elements of dates (including year) indicative of such age (except for an aggregate into a single category of age over 90 years) |

|

• Telephone numbers |

|

• Fax numbers |

|

• Electronic mail addresses |

|

• Social Security numbers |

|

• Medical-record numbers |

|

• Health-plan beneficiary numbers |

|

• Account numbers |

|

• Certificate and license numbers |

|

• Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license-plate numbers |

|

• Medical-device identifiers and serial numbers |

|

• Internet universal resource locators (URLs) |

|

• Internet protocol (IP) addresses |

|

• Biometric identifiers, including fingerprints and voiceprints |

|

• Full-face photographic images and any comparable images |

|

• Any other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code, except that covered identities may, under certain circumstances, assign a code or other means of record identification that allows deidentified information to be reidentified |

SOURCE: MMWR, 2003; 45 CFR § 164.514(b)(2)(i).

volved (Pritts, 2008). In such circumstances, the Privacy Rule permits a covered entity to use and disclose PHI for research purposes without obtaining authorization from each patient if an IRB reviews a research proposal and determines that it is appropriate to grant a waiver of authorization (45 CFR § 164.512(i)(1)(i)).

The HIPAA Privacy Rule does not cover such materials as biospecimens themselves, but it does cover the PHI associated with them. Biospecimens in the JPC repository generally do have data associated with them that would qualify as PHI.

The Common Rule

The Common Rule grew out of HHS regulations to protect human subjects in research that were first published in 1974 (45 CFR Part 46) in response to the revelation of serious breaches of respect for and protection of participants in research, including cases noted earlier in this chapter. In 1991, the central portion of those regulations (45 CFR Part 46, Subpart A) was adopted by many federal agencies, including the DoD, in response to an initiative to achieve uniformity of federal regulations on human-subjects protection, eliminate unnecessary regulations, and promote increased understanding by institutions that conduct federally supported or regulated research—this is the Common Rule.19 It governs most federally funded research conducted on human beings and aims to ensure that the rights of human subjects are protected during the course of a research project. The Common Rule stresses the importance of individual autonomy and consent, requires independent review of research by an IRB, and seeks to minimize physical and mental harm. Privacy and confidentiality protections are included as important protections against some kinds of risk in research. The framework for achieving the goal of protecting human subjects is based on two foundational requirements: the informed consent of the research participant and the review of proposed research by an IRB.

In general, the Common Rule applies only to research on human subjects that is supported or conducted by the federal government or performed by an institution (such as a university) that commits to conducting non-federally supported research in compliance with human-subjects research regulations via a Federalwide Assurance (45 CFR § 46.101).20 Research is defined as “a systematic investigation, including research

___________________

19To the extent that an agency needed to modify the general version because of the types of research it sponsors or special features of the research population, it could do so through a short separate rule.

20The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) human-subjects protection regulations apply to research in development of all products that require FDA approval.

development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge” (45 CFR § 46.102(d)). Under the Common Rule, a “human subject” is defined as “a living individual about whom an investigator … conducting research obtains (1) Data through intervention or interaction with the individual, or (2) Identifiable private information” (45 CFR § 46.102(f)).

Data are considered personally identifiable if the identity of a subject is or may be readily ascertained by the investigator or associated with the information accessed by the researcher (45 CFR § 46.102(f); OHRP, 2008b). However, the Common Rule exempts from its requirements (45 CFR § 46.101(b)(4)) research that involves solely

the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathological specimens, or diagnostic specimens, if these sources are publicly available or if the information is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects.

Some research on human biospecimens and associated data does not constitute research on human subjects as defined by the Common Rule. OHRP has issued guidance on ethical approaches to such research on human materials (2008a,b), sometimes called “human nonsubjects research” (Brothers and Clayton, 2010). In 2011, HHS issued an ANPRM to elicit comments on possible changes to the Common Rule that would affect both human-subjects research and some human nonsubjects research (HHS, 2011). That rule making was still in progress when the present report was completed (the middle of 2012).

Under OHRP guidance, the research use of specimens or data not originally collected for that research is not considered research on human subjects under the Common Rule if the investigators cannot readily identify the source individuals (OHRP, 2008b). That suggests that under current rules, if a repository removes identifiers linked to individual sources from the clinically derived specimens and data it makes available to researchers, such that the sources cannot individually be readily identified by the researchers, research conducted using these specimens or data would not constitute human subjects research under the Common Rule (OHRP, 2008a; Wolf et al., 2012). Data that are otherwise identifiable may be deidentified for purposes of the Common Rule if they are coded and some other conditions are met (HHS, 2004). Under guidance issued by OHRP (2008a), information is “coded” if data (such as name or Social Security number) that would enable the investigator to readily ascertain the identity of the individual to whom the private information or specimens pertain has been replaced with a number, letter, symbol, or combination thereof (the code) and there is a

key for deciphering the code and enabling linkage of the identifying information to the private information or specimen.

Differences Between the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Common Rule

Table 3-2 presents in schematic form some of the major provisions of HIPAA and the Common Rule and how the two differ. These differences are explicated below.

Both the Common Rule and HIPAA allow waivers or alterations of the requirement for informed consent if certain criteria are met. The Common Rule allows a waiver (45 CFR § 46.116(d)) provided the IRB finds and documents that

(1) the research involves no more than minimal risk to the subjects;

(2) the waiver or alteration will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects;

(3) the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver or alteration; and

(4) whenever appropriate, the subjects will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation.

A waiver of HIPAA authorization is similar to (but not identical with) a waiver of consent requirements under the Common Rule. A waiver of authorization is permitted (NIH, 2012) when

(1) Use or disclosure involves no more than minimal risk to the privacy of individuals because of the presence of at least the following elements:

(a) An adequate plan to protect health information identifiers from improper use or disclosure,

(b) an adequate plan to destroy identifiers at the earliest opportunity absent a health or research justification or legal requirement to retain them, and

(c) adequate written assurances that the PHI will not be used or disclosed to a third party except as required by law, for authorized oversight of the research study, or for other research uses and disclosures permitted by the Privacy Rule;

(2) research could not practicably be conducted without the waiver or alteration; and

(3) research could not practicably be conducted without access to and use of PHI.

TABLE 3-2 HIPAA and Common Rule Human-Subjects Protection Regulations

| Category of Distinction | HIPAA Privacy Rule: Title 45 CFR Part 164 | HHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations: Title 45 CFR Part 46 (Common Rule) | ||

| Overall objective | To ensure that individuals’ health information is properly protected while allowing the flow of health information needed to provide and promote high-quality health care. | To protect the rights and welfare of human subjects involved in research conducted or supported by any federal department or agency. | ||

| Applicability or scope | Applies to health plans, health care clearinghouses, and any health care provider that transmits health information in electronic form. | Applies to all research involving human subjects conducted, supported, or otherwise subject to regulation by any federal department or agency subscribing to the CommonRule. | ||

| Definition of research or clinical investigations | Defined as a systematic investigation—including research development, testing, and evaluation—designed to develop or contribute to generalized knowledge. | Defined as a systematic investigation—including research development, testing, and evaluation—designed to develop or contribute to generalized knowledge. | ||

| Definition of human subjects | Defined as the individual (or the individual’s personal representative) who is the subject of the health information being used or disclosed. | Defined as a living person about whom an investigator conducting research obtains data through intervention or interaction with the person or identifiable private information. | ||

| IRB or privacy board requirement | Required for projects involving requests to alter or waive the individuals’ authorization for the use or disclosure of their protected health information for research purposes. | Required for all projects involving human subjects supported, conducted, or regulated by a federal department or agency. | ||

| IRB or privacy board responsibilities | To review all requests to alter or waive the individuals’ authorization for the use or disclosure of their protected health information for research purposes; not required to review or approve authorizations. | To ensure that informed consent will be sought from and documented for each prospective subject or the subject’s legally authorized representative in accordance with and to the extent required by HHS regulations; to ensure that adequate provisions are taken to protect the privacy of subjects and to maintain the confidentiality of data.(Other conditions not specific to biorepositories apply.) |

| Category of Distinction | HIPAA Privacy Rule: Title 45 CFR Part 164 | HHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations: Title 45 CFR Part 46 (Common Rule) | ||

| IRB or privacy board exemptions | Research involving personal health information if it is deidentified by the “SafeHarbor Method,”a if validation is obtained from a statistician that the risk that the information could be used by the anticipated recipient to identify the subject of the information is very small, or if only a “limited dataset”b is used or disclosed. | Research involving the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathologic specimens, or diagnostic specimens; and research involving only coded private information or specimens so that the subject’s identity cannot be readily ascertained if the research does not qualify as human-subjects research. (Other conditions not specific to biorepositories apply.) | ||

| Permissions for research or use of private information | Authorization. | Informed consent. | ||

| What qualifies as identifiable information? | All “individually identifiable health information” held or transmitted by a covered entity or its business associate in any form or medium, whether electronic, paper, or oral. | Any form or medium in which the identity of the subject is or may readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects, by the investigator or person associated with the information. | ||

| Qualifications for a waiver of authorization or informed consent | If use or disclosure involves no more than minimal riskc to the privacy of individuals, research could not practicably be conducted without the waiver or alteration, and research could not practicably be conducted without access to and use of protected health information. | If the research involves no more than minimal risk to the subjects, the waiver or alteration will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects, the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver or alteration, and, when appropriate, the subjects will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation. (Other conditions not specific for biorepositories apply.) |

SOURCE: Adapted from HHS, 2003b.

aThe “Safe Harbor Method” states that 18 identifiers of the individual or of relatives, employers, or household members of the individual must be removed. These identifiers are listed in Table 3-1.

bA limited dataset may include such information as dates and locations. It may be used or disclosed only for public-health, research, or healthcare operations purposes, and it is subject to other requirements (45 CFR 164.514(e)).

cIn order to qualify as minimal risk there must be an adequate plan to protect health-information identifiers from improper use or disclosure, an adequate plan to destroy identifiers at the earliest opportunity in the absence of a health or research justification or legal requirement to retain them, and adequate written assurances that personal-health information will not be used or disclosed to a third party except as required by law, for authorized oversight of the research study, or for other research uses and disclosures permitted by the Privacy Rule.

Because both the Common Rule (and OHRP guidance) and HIPAA rules refer to deidentification as a condition for a waiver, it is important to recognize that HIPAA defines this level of deidentification differently from the Common Rule. The HIPAA Privacy Rule generally defines deidentified PHI as information that “does not identify an individual and with respect to which there is no reasonable basis to believe that the information can be used to identify an individual” (164.514(a)). It does not require there to be no risk of reidentification but instead that “the risk [be] very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is a subject of the information” (emphasis added) (164.514(b)(1)(i)). To meet that standard of deidentification, the 18 specific identifiers listed in Table 3-1 must be removed or a statistical certification must be made that states that the risk of reidentification is very small. In addition, “the covered entity does not have actual knowledge that the information could be used alone or in combination with other information to identify an individual who is a subject of the information” (164.514(b)(2)(ii)).

Another conflict between the Common Rule and HIPAA is in coverage of deceased individuals. Although the Common Rule restricts its definition of “human subjects” to living individuals, HIPAA applies to both the living and the deceased. HIPAA requires assurance from researchers who seek to use or disclose PHI from deceased persons that With and colleagues (2011) summarize as follows:

(1) that the use and disclosure of PHI is solely for research,

(2) that the PHI is necessary for the research, and

(3) that documentation of death … be provided, if requested by the covered entity.

HIPAA authorization applies to a specific research protocol, not to a general intent to use the PHI in research in the future. Current HIPAA regulations do not permit broad consent to future research without waiver of the authorization requirements (Clayton, 2005). In response to public comments on HIPAA, the Office of Civil Rights (which administers HIPAA) noted that “the Department disagrees with broadening the required ‘description of the purpose of the use or disclosure’ because of the concern that patients would lack necessary information to make an informed decision” (67 Fed. Reg. 53,226). Authorization to use PHI, it asserted, must be “specific and meaningful,” and general descriptions are inadequate (HHS, 2011; Wendler, 2006).

Potential Changes in the Common Rule Under the 2011 Department of Health and Human Services Advance Notice of Proposed Rule Making

The federal rules governing research on samples collected for clinical purposes were in flux when the present committee completed its work in the middle of 2012. As already noted, HHS issued an ANPRM in July 2011 requesting comments on possible regulatory changes that would alter required consent for research. Consent is currently required unless research falls under the deidentification exceptions, including waivers, contained in the Common Rule and the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Much of the justification for not requiring consent rests on the idea that as long as participants remain unidentifiable, potential harm is so limited that it makes consent unnecessary. The ANPRM, however, noted growing recognition that identifiability is a fluid concept that advances with technology and that what was formerly considered deidentified could be identifiable with advances in technology and increased information flow. Thus, current justifications for foregoing consent or HIPAA authorization were not necessarily sustainable.

The ANPRM therefore proposed that written consent for possible future use in research be required for “any biospecimens collected for clinical purposes after the effective date of the new rules.” That would include all specimens taken in the course of clinical care for use in research even if later deidentified. However, the consent required would be broad, “would allow for waiver of consent under specified circumstances” and would “generally permit future research.” That differs from policy in place in 2012 that generally disfavors broad consent and broad authorization for future research and does not require consent for research on specimens collected in clinical care that can be deidentified (HHS, 2011). The fate and scope of any actual change in regulatory language based on the ANPRM remained uncertain when this report was finished.

Military Rules Addressing Human-Subjects Research and Privacy