Many glaciers and snowpacks around the world are receding. This recession results from glacial ablation (melt and sublimation) rates that exceed the rates of glacial formation and accretion from precipitation over time. The rates and timing of glacial retreat vary across hemispheres, regions, and locales. The causes of such retreat are complex and although climatic warming is an important cause, care must be taken to recognize that in most instances there are multiple influences that interact in ways that are difficult to predict.

Initially, glacial wasting increases the volumes of glacial meltwater in downstream waterways. As a glacier continues to waste, a point will be reached at which the volumes of meltwater begin to decline and ultimately become zero when the glacier has disappeared (although precipitation falling on the land area previously occupied by the glacier will continue to contribute to downstream flows). Wherever glaciers are wasting continuously, there are concerns about the consequences for available water supplies.

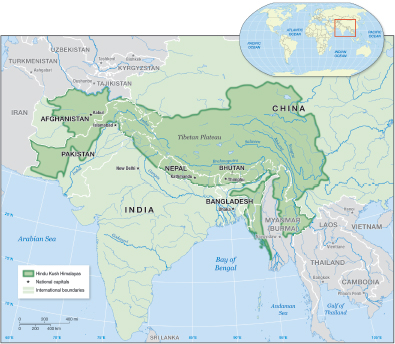

Mountains are the water towers of the world and in many regions, the volume and timing of streamflow from glacial and snowmelt are critical for agricultural production, hydropower generation, water supply, and the functioning and health of ecosystems. In the Hindu Kush-Himalayan (HKH) region (Figure 1.1) in particular, the large populations of China and South Asia rely on both the water and electricity generation provided by the major rivers. Many basins in the HKH region are “water stressed” (Figure 1.2), and this stress is projected to increase due to large forecasted population growth. This has led to concern about potential negative impacts from changes in the availability of water supplies in the coming decades.

Although many glaciers across the globe have retreated over recent decades, the rates of retreat and mass loss can vary widely, indicating that a variety of regional-scale factors such as changes in circulation, cloudiness, precipitation, aerosol concentration, glacier geomorphology, tectonic activity, and debris cover, in addition to warming, can affect glaciers. A recent assessment of glaciers in the region using a combination of remote sensing and in situ data found different patterns of glacial retreat within the HKH region (Yao et al., 2012). Thus, a diverse range of factors affects the timing and amount of glacier-fed streamflow, with significant potential implications for water availability and regional stability. A recent Intelligence Community Assessment found that South Asia is one of three regions likely to be challenged by water scarcity in the coming decades (DNI, 2012).

In the HKH region, conventional wisdom is that glacial meltwater is an important supplement to naturally occurring runoff from precipitation and snowmelt. While correct, the watersheds of the area each exhibit complex hydrology, and the magnitude of the contribution of glacial meltwater to the total water supply in these rivers is less clear. The implications of accelerated rates of glacial wastage for downstream populations have not been precisely characterized.

Despite this fact, or perhaps because of it, there is confusion about how changes in the climate will affect the timing, character, and rates of glacial wastage in different parts of the HKH region. Scientific evidence indicates that glaciers in the eastern and central part of

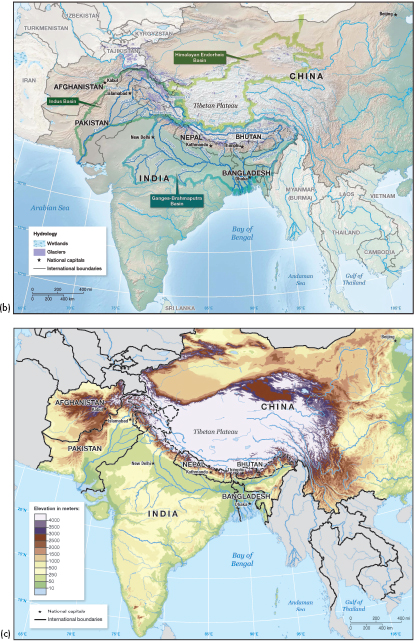

FIGURE 1.1 The Hindu-Kush Himalayan region extends over 2,000 km across South Asia and includes all or parts of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. The region is the source of many of Asia’s major rivers, including the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra.

this region are retreating at rates comparable to those in other parts of the world, but are relatively stable, and perhaps even advancing, in parts of the western Himalayas. These findings, the findings of recent reviews by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID, 2010) and the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD, 2011b), and evidence presented later in this report bring into question the results of several earlier studies: one suggested that the glaciers of the HKH would disappear altogether by 2035; another suggested that the origins of accelerated glacial wastage lie with the Medieval Warm Period1 that occurred over a thousand years ago. Neither of these assertions is supported by scientific evidence, and they have served to create unnecessary confusion. There is also confusion about the ultimate implications of these changes for domestic, industrial,

_________

1 The Medieval Warm Period was a period of warmer climate in much of northern Europe, the North Atlantic, southern Greenland, and Iceland. It lasted from roughly A.D. 950 to 1250. It is the “Medieval” Warm Period because it coincided with Europe’s Middle Ages (AMS, 2000).

FIGURE 1.2 Global map of water-stressed basins. The water stress indicator is the ratio of total water withdrawals to calculated in-stream flow requirements. Many basins in the HKH region have “high” levels of water stress. SOURCE: Smakhtin (2008).

and agricultural water availability as well as for the various in-stream ecological uses.

In addition, in the context of incomplete science and unresolved uncertainties, there are other important questions about regional water security that need to be addressed. From the beginning the Committee was mindful that it would need to sort out these confusions and resolve any resultant misunderstandings in order to successfully address the statement of task (Box 1.1). Included among the questions examined by the Committee in the course of addressing their charge are the following:

• What are the rates of retreat of the Himalayan glaciers over the last decades and how do they compare with the rates of retreat of glaciers elsewhere in the world?

• Are the rates of glacial retreat in the study region accelerating, decelerating, or remaining static?

• What proportion of the seasonal flows of the Indus and Ganges/Brahmaputra rivers are accounted for by glacier melt?

• What has been the impact of recent climate change on both glacial wastage and streamflow in the region?

• Has the relative contribution of glacier meltwater to dry-season or wet-season flows increased, decreased, or remained static?

• Would the deglaciation of the HKH region imply that the area is headed toward water scarcity within the next few decades?

• Over the next several decades,2 how will these high-altitude changes in climate and hydrology compare, and interact with, other economic, social, and demographic impacts on regional water supply and demand?

• Does the retreat or accelerated retreat of HKH glaciers increase the likelihood of natural disasters such as outburst floods from moraine dammed lakes or seasonal flooding?

Available science does offer some important information that leads to conclusions that are relevant to these questions.

STUDY CONTEXT AND

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

This report was prepared by the Committee on Himalayan Glaciers, Hydrology, Climate Change,

_________

2 Wherever possible, the Committee has attempted to limit its projections to the order of three to four decades at most. However, in some cases this was not possible. For example, decadal-scale climate projections are currently an area of active research, and the climate modeling community has more skill in projecting climate over longer timescales.

BOX 1.1 Committee on

Himalayan Glaciers, Hydrology,

Climate Change, and Implications

for Water Security Statement Of Task

The Committee was charged to explore the potential impacts of climate change on glacier-fed streamflow and regional water supplies in one region, the Himalayas. The glaciers in this region are the headwaters of several of Asia’s great river systems, including the Ganges/Brahmaputra, Indus, Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers. These rivers are the sources of drinking water and irrigation supplies for billions of people. These rivers also generate hydropower and support important ecological values, such as fisheries. The Committee was asked to summarize the current state of scientific understanding on questions such as

• How sensitive are the Himalayan glaciers to changes in temperature, precipitation, and the surface energy budget?

• What does current glaciological and climatological knowledge imply about potential changes in climate on downstream flows? What are the likely major impacts on water supplies and flood regimes? What additional observational and modeling resources are needed to improve knowledge of hydro-climate trends and forecasts?

• What management systems (including water supply, water demand, land use, and other institutions and infrastructure) are in place to manage climate-induced changes in regional hydrology, and how might they be strengthened? In addressing this question, the Committee will analyze the advantages and disadvantages of various options for improving existing management systems, which could include consideration of new management systems, but will not recommend specific options.

• What are some of the main vulnerabilities to adjusting to changes in water supply in these downstream areas? What are the prospects for increased competition, or improved cooperation, between different downstream water users? What are some of the implications for national security?

To inform its analysis, the study Committee was supported by information gathered at an interdisciplinary workshop, using both invited presentations and discussion to explore the issues that may affect regional streamflow and water supplies in the face of a changing climate. The Committee examined a few selected examples of changes in glacial melt and resultant streamflow for a specified time horizon as a way of developing boundaries for the workshop discussion. The thinking at the workshop took the form of linking potential changes in temperature and precipitation to a range of changes in glacial mass balance and regional hydrology, which in turn could lead to a range of outcomes for downstream streamflow and water security, including water supplies and flooding regimes.

and Implications for Water Security, appointed by the National Research Council (NRC) in response to a request from the intelligence community, to address the broad charge of identifying what is known scientifically about the glaciers of the Himalayas, their likely future, and the implications of that future on downstream water supplies and populations (see Box 1.1 for full Statement of Task). Part of its purpose was to clarify, where possible, many of the misunderstandings surrounding the broad topic of glacial retreat and its implications in the Himalayas and surrounding region. Recognition of the significance of potential impacts of climate change on glacier-fed streamflow and regional water supplies in the Himalayas led to the commissioning of this study.

The focus of this study is the HKH region, which extends over 2,000 km from east to west across the Asian continent spanning several countries (Figure 1.1): Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. The eastern and western areas of the HKH region differ in climate, especially in timing and type of precipitation, and in glacier behavior and dynamics as well. For glaciers, there is no sharp dividing line between east and west; rather, conditions change gradually across the region (e.g., glacier mean elevation; Scherler et al., 2011a). The eastern end is dominated by monsoonal activity in summer while the western end is dominated by the mid-latitude westerlies3 in winter (Thayyen and Gergan, 2010). The monsoon declines in strength from east to west along the Himalayas, while the westerlies weaken as they move from west to east. This gradient divides at about 78 °E near the Sutlej valley (Bookhagen and Burbank, 2010). To the west (Afghanistan; Kashmir and Jammu, India; western Nepal; Pakistan), there is a general pattern of winter accumulation and summer melt, similar to glaciers in North America and Europe. In contrast, to the east (Bhutan; Sikkim, India; eastern Nepal), glaciers are summer accumulation types, where both maximum

_________

3 The mid-latitude westerlies (westerlies) are the dominant west-to-east motion of the atmosphere, centered over the middle latitudes of both hemispheres. At the Earth’s surface, they extend from roughly 35° to 65° latitude (AMS, 2000).

accumulation and maximum ablation4 occur during the summer. River discharge5 in the eastern end of the HKH arc appears to be driven by monsoonal activity. Large areas of the Indus river systems are dominated by winter snowfall from the westerlies. Monsoon activity is lower and precipitation is dominated by winter snow in the upper Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab basins. Ladakh, which extends from Tibet to India, is a unique cold-arid region (Thayyen and Gergan, 2010).

The political and hydrological boundaries within the study areas are both important and add useful clarity to the study area definition. The political boundaries in the region are shown in Figure 1.3a. The countries found in the study area include all or portions of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. As the map indicates, some of the political boundaries are disputed, and boundary disputes are likely to remain a potential source of instability for the indefinite future.

The glaciers of the region are found in the headwaters of several of Asia’s great river systems, including the Indus, Ganges/Brahmaputra, Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers. These rivers are the source of drinking water and irrigation supplies for roughly 1.5 billion people. They also generate significant quantities of hydroelectric power and support important ecological and cultural amenities and services. The surface water of these rivers and associated groundwater constitute a significant strategic resource for all of Asia, which is among the most water stressed regions of the world (Smakhtin, 2008).

The specific study area for this report includes the catchments of the Indus and Ganges/Brahmaputra rivers. The committee defined the primary scope of their report as the countries that include all or part of the Indus, Ganges, or Brahmaputra basins, including

_________

4 Ablation includes any process that removes ice from a glacier.

5 River or stream discharge is the volumetric rate of flow (AMS, 2000).

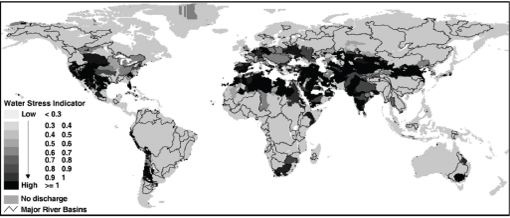

FIGURE 1.3 The (a) political boundaries, (b) hydrology, and (c) elevation of the Hindu-Kush Himalayan region. Dashed lines are used to indicate disputed political boundaries, which follow the guidance issued by the U.S. State Department, and this Committee takes no position on these boundary disputes. continued

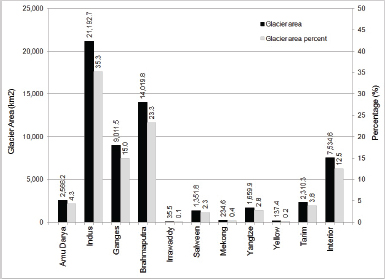

the portion of the Tibetan Plateau included in those basins. According to the committee’s charge, the areas of major concern are those where the water supply for a significant population could be influenced by changes in the region’s glaciers. Figure 1.4 shows the percentage of glaciated area within the river basins of the HKH region. The Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra basins combined contain nearly three-quarters of the region’s glaciated area. Except for the interior basins (labeled as Himalayan Endorheic basins in Figure 1.3c), the other river basins each contain less than 5 percent of the region’s glaciated area. The Committee includes some discussion of the part of the region covered by the Endorheic basins in Chapter 2, Physical Geography, particularly in the section on ice core data (see Figure 2.14). Because the population density of the Tibetan Plateau is very small (see Figure 3.1), it follows that very few people depend on the interior basins for water supply, and any glacier-related changes to the water supply in those basins would not affect a large number of people. Thus the focus of Chapter 3, Human Geography and Water Resources is on the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra basins.

Although the Mekong originates on the Tibetan Plateau and is the source of water for the populations of Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, glaciers are a small component of water resources in the Mekong (Figure 1.4). The Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, which provide water for large parts of China, also originate on the Plateau and have relatively small glacial coverage (Figure 1.4). Because the Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow River basins contain a relatively small amount of glacier area, it follows that discharge into these rivers results from snowmelt and rainfall. As discussed in Chapter 2, in most basins, the contribution of rain far outweighs the contributions of snowmelt (e.g., Andermann et al., 2012). These three rivers are located in the eastern part of the HKH region, where annual precipitation is dominated by the summer monsoon (Bolch et al., 2012). On the basis of these considerations, discharge into the Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers is more influenced by the monsoons, and in the future, climate change effects on the monsoon will play a greater role than any changes in the glaciers.

It is common to refer to the Tsangpo/Brahmaputra to indicate that the upstream portion of the river on

FIGURE 1.4 Glacier area and percentage of total HKH glaciated area in each of the region’s river basins. Only the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, and interior basins of the Tibetan Plateau contain more than 5 percent of the region’s glacier area. SOURCE: ICIMOD (2011b).

the Tibetan Plateau is called Tsangpo, while the Brahmaputra is the proper name of the river once it enters India. To avoid confusion, the river is referred to as the Brahmaputra throughout this report. In this report, when discussing issues on a watershed basis, the Ganges and Brahmaputra are grouped as a single watershed because they eventually merge before draining into the Bay of Bengal. However, when discussing hydrological issues—for example, river hydrographs6—the Ganges and Brahmaputra are treated separately. The tributaries of the Indus and the Ganges/Brahmaputra Rivers are depicted in Figure 1.3b.

The HKH region is geographically vast and complex both climatologically and hydrologically and this complexity is dynamic and possibly changing. This means that it is very difficult to generalize observations and findings over the entire region because spatial variability is large. The story that emerges in this report is also characterized by the fact that there remain many open science questions that cannot be answered in the absence of additional data and research. Although global temperatures are increasing generally, and these increases have been more rapid in recent decades, spatial variability and lack of local research data mean that the specific manifestations of climate change are unclear in the HKH region. This includes how quickly and regionally glaciers might retreat, and what the subsequent impacts on the hydrological system of the HKH region might be. In recognition of the complexities of these issues, NRC formed the Committee on Himalayan Glaciers, Hydrology, Climate Change, and Implications for Water Security to begin to address some of these important questions.

STUDY APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY

The Committee was formed in summer 2011 and completed its work over the course of the next 12 months. It held four meetings during which it reviewed relevant literature and other information. To inform its analysis, the Committee organized an interdisciplinary workshop, using both invited presentations and discussion to explore the issues that may affect regional streamflow and water supplies in the face of a changing climate. The workshop, which was held in fall 2011 in Washington, D.C., was organized around four broad themes: (1) regional climate and meteorology; (2) regional hydrology and water supply, use, and management; (3) regional demography and security; and (4) risk factors and vulnerabilities. The workshop agenda and participants are included in Appendix A, and workshop presentation summaries are included in Appendix B. Workshop participants identified key concepts about the HKH region. Starting from those concepts, the Committee used its expert judgment, reviews of the literature, and deliberation to develop conclusions about the physical geography, human geography and water resources, and environmental risk and security in the HKH region. These conclusions are listed at the end of each chapter.

This report covers three broad areas of knowledge about the Himalayan region: (1) physical geography, (2) human geography and water resources, and (3) environmental risk and security. Chapter 2, Physical Geography, provides an overview of glaciers, followed by a summary of the climate and meteorology of the region within the context of paleoclimate patterns, and descriptions of the regional hydrology and physical hazards. Chapter 3, Human Geography and Water Resources, covers population distribution, poverty and migration, and key natural resource issues of water use, access to water, water scarcity, and water management. Chapter 4, Environmental Risk and Security, presents the Committee’s further analyses of the linkages between physical and human systems, with an emphasis on those that may pose potential instabilities for the region. Chapter 5 presents the Committee’s synthesis of the range of physical and social changes facing the region, a summary of research questions and data needs, and options for adapting to the changes facing the region.

_________

6 A hydrograph is a record and graphical representation of river or stream discharge as a function of time at a specific location (AMS, 2000).