“Anticipating and preparing for potential problems

rather than reacting to events puts us in a

better place when dealing with natural disasters.”

Citizen from Curry County, Oregon

1

The Nation’s Agenda for Disaster Resilience

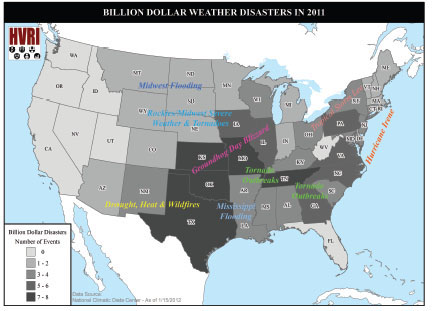

In 2011 the United States was struck with multiple disasters including 14 weather- and climate-related events that each caused more than $1 billion in damages1 (Figure 1.1). Statistics indicate that total economic damages from all natural disasters in 2011 exceeded $55 billion in property damage, breaking all records since these data were first reported in 1980 (NCDC, 2012). Cumulatively, nearly 600 Americans died2 and many thousands of households were temporarily or permanently displaced by events that included blizzards, tornadoes, drought, flooding, hurricanes, and wildfires (Figure 1.2). Natural disasters have continued in 2012 as this report was being written—with tornadoes, massive wildfires, and flooding and wind damage affecting millions of people in the nation. These events have had local and national ramifications, and effects from them have been felt across large geographic areas and large portions of the population through injuries and death, destruction of homes and businesses, displacement of people, interruption of business, disruptions in transportation, job losses, and greater demands on federal and state resources. These disasters demonstrate very clearly the interconnectedness of natural and human systems and infrastructure and the strengths and frailties of these connections.

No person or place is immune from disasters or disaster-related losses. Infectious disease outbreaks, acts of terrorism, social unrest, or financial disasters in addition to natural hazards can all lead to large-scale consequences for the nation and its communities. Communities and the nation thus face difficult fiscal, social, cultural, and environmental choices about the best ways to ensure basic security and quality of life against hazards, deliberate attacks, and

______________

1http://www.noaa.gov/extreme2011/

2http://www.emdat.be/result-country-profile?disgroup=natural&country=usa&period=2011$2011.

disasters. One way to reduce the impacts of disasters on the nation and its communities is to invest in enhancing resilience.

FIGURE 1.1 Areas in the United States affected by large weather disasters in 2011. HVRI = Hazards and Vulnerability Research Institute. Source: S. Cutter/HVRI.

The large amounts of money the federal government spends in responding to disasters are one indicator of the urgency of the need to increase the nation’s resilience to these events. These expenditures are borne by the entire nation and have been growing steadily for the last 60 years, both in absolute terms and on a per capita basis. For example, in 1953, the first year of presidential disaster declarations, federal expenditures totaled $20.9 million (adjusted to 2009 dollars) or $0.13 per person. In 2009, with many more disaster declarations, the federal government conservatively spent $1.4 billion on federal disaster relief or the equivalent of about $4.75 per person.3 The past two decades in particular show highly devastating and costly events to the nation’s treasury: the 1994 Northridge earthquake led to federal expenditures of $11.6 billion in disaster relief, relief costs for the 2001 World Trade Center attack totaled $13.3 billion, and Hurricane Katrina alone in 2005 led to more than $48.7 billion in federal disaster relief costs. Importantly, these expenditures do not even include insured property or business interruption losses, which

______________

3 Computed from Federal Emergency Management Agency Presidential Disaster Declaration Data with totals adjusted to 2009 dollars.

otherwise significantly increase the total economic impact of these events. For example, property damage at the World Trade Center stemming from the 9/11 terrorist attacks amounted to $23 billion, but the costs for business interruption are estimated to have been around $100 billion (Rose and Blomberg, 2010).

FIGURE 1.2 Tornado damage in Joplin, Missouri, from the May 2011 tornado that struck the area, killing 159 people and injuring more than 1,000 others. The tornado was the single deadliest in U.S. history since such records have been kept. The tornado was 1 mile wide and traveled 22 miles on the ground (NOAA, 2011). Source: Charlie Riedel/AP Photo.

What happens to the magnitude of these losses of lives, livelihoods property, and community in the future as our population increases and our infrastructure ages and expands if we maintain the status quo and our nation does not improve its resilience to hazards and disasters? What does effective disaster resilience look like for the nation, for our communities, and for our families? What steps need to be taken to become more resilient in the near and long term?

THE NATIONAL IMPERATIVE TO INCREASE RESILIENCE

Decisions by communities, states, regions, and the nation regarding whether to invest in building resilience are difficult. If building the culture and practice of disaster resilience were simple and inexpensive, the nation would likely have taken steps to become more resilient already. Making the choice either to proceed with the status quo—where concerted investments and planning do not take place throughout the country to increase disaster resilience—or to make conscious decisions and investments to build more resilient communities is weighted by a few central points:

1) Disasters will continue to occur, whether natural or human-induced, in all parts of the country;

2) The population will continue to grow and age as will the number and size of communities; in some regions population decline and the number and size of communities will create a different set of challenges as tax bases decline;

3) Demographic data demonstrate that more people are moving to coastal and southern regions-areas with a high number of existing hazards such as droughts and hurricanes;

4) Public infrastructure is currently aging beyond acceptable design limits;

5) Infrastructure such as schools, public safety, and public health that are essential to communities are facing economically difficult times as the population grows and ages;

6) Economic and social systems are becoming increasingly interdependent and thus increasingly vulnerable should a key part of the system be disrupted;

7) Risk cannot be eliminated completely, so some residual risk will continue to exist and require management;

8) Impacts of climate change and degradation of natural defenses such as coastal wetlands make the nation more vulnerable.

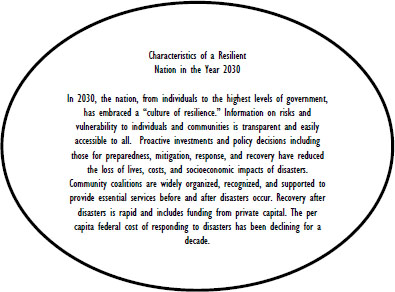

This report suggests some of the characteristics of a resilient nation in the year 2030. This future vision of characteristics that the United States might have in 2030 requires alternative kinds of decisions and investments that will lead to a more resilient nation:

The nation has an important stake in realizing the characteristics of this future vision. Achieving this kind of resilience in two decades encompasses actions and decisions at all levels of government, in the private sector, and in communities including, for example,

• Action by federal agencies to incorporate disaster risk and resilience in their policies and activities. Such actions could include strong support for monitoring activities and data collection for natural and human systems (Appendix C), and transfer and communication of resilience-related research to states, regions, and communities. Such data and research are critical for quantifying risk and measuring progress for resilience.

• Consistent federal assistance for community resilience based on loss avoidance or disaster risk reduction, rather than primarily on post-disaster relief.

• Nationwide infrastructure upgrades by both the private sector and all levels of government to meet 21st century technology needs and building codes and to encompass disaster-resilient designs.

• Increased nationwide increased support for public safety, health, and education as well as information systems.

• Commitment from local city and county officials to maintain and advocate land use, zoning plans, and construction codes that explicitly enhance resilience and emphasize working with the natural environment and valuing natural environmental defenses.

• Recognition at all levels of government and within communities that communities are part of a system that includes both the natural environment and other communities. Implicit in this recognition is the idea that actions to enhance a single community’s resilience, such as constructing a flood defense system, may have positive and negative impacts on surrounding communities over time.

• Realization by individuals and communities that they provide their own first line of defense against disasters, including mutual assistance and governance structures designed to manage crises cooperatively.

This resilient future also includes understanding the economic benefits of resilience, such as the cost savings of mitigation, and valuing the protective functions and services of ecosystems. The costs for short-term mitigation alone can reduce much greater, longer-term losses. For example, the Multihazard Mitigation Council (2005) found that every dollar spent on pre-event mitigation related to earthquakes, wind, and flooding saved about $4 in post-event damages. Furthermore, the planning and preparation for one type of disaster (such as the nuclear accident planning experience in Cedar Rapids, Iowa—see Box 2.4), can reap benefits for other types of disasters or unexpected adverse events.

An alternative to the resilience vision is the current path of the nation— the status quo in which innovations are not made to increase the nation’s resilience to hazards and disasters. Unless this current path in the nation’s approach toward hazards and disasters is changed, data suggest that the cost of disasters will continue to rise both in absolute dollar amounts and in the losses to the social, cultural, and environmental systems that are part of each community. Communities that continue to build in areas such as floodplains, wetlands, and coastal zones may experience greater impacts from flooding, hurricanes, and sea-level rise (e.g., NRC, 2012). Continued reliance on structural or engineered solutions to control nature rather than to work in concert with natural systems may transfer and enhance disaster risks across geographic areas and through time. Businesses and households may remain vulnerable because of inadequate building and zoning codes. Vulnerable people such as the elderly or those with specific health issues will need more extensive and expensive assistance in a disaster. Increased property, job, and crop losses may result in greater demand for disaster relief funding from the federal government.

The various points relevant to increasing the nation’s resilience, including the characteristics of a resilient nation in 2030, are developed in later chapters.

RESILIENCE DEFINED AND THE ROLE OF THIS STUDY

Many people have heard and used the term “resilience,” perhaps in describing how an individual or a city or a nation showed great strength under adversity, or bounced back after some unexpected tragedy. After such events, an individual or city or nation can become stronger, its approaches and institutions more flexible, and its citizens and communities more capable of withstanding the next adverse circumstance. In addressing the broad topic of resilience, articulating what is meant by the term is important. This report defines resilience as the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events (Definition 1.1).

Definition 1.1

Resilience: The ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, or more successfully adapt to actual or potential adverse events.4

______________

4 This definition was developed by the study committee based on the extant literature and is consistent with the international disaster policy community (UNISDR, 2011), U.S. governmental agency definitions (SDR, 2005; DHS Risk Steering Committee, 2008; PPD-8, 2011), and NRC (2011).

This report considers resilience to disasters to encompass both natural and human-induced events. However, most of the data and information on disasters relate to those with natural causes and the report is weighted toward using those events as examples. The report addressed the importance of an “all-hazards” approach to resilience that encompasses the idea that planning for one kind of hazard or disaster event can increase the resilience of a community in the face of a different kind of event. When this concept of resilience is applied to hazards and disasters, whether natural or human-induced, being able to anticipate, withstand, and recover from such events with minimal human and economic losses becomes a very desirable goal. Further, being resilient to hazards and disasters is a condition toward which all communities and the nation can justifiably aspire. Despite efforts to reduce the impact of natural disasters, however, the United States as a whole is not fully resilient to disasters.

Communities and the nation can be better protected and strengthened by increasing resilience to disasters just as individuals take preventive measures to protect the human body against illness and disease (Box 1.1). A healthy body is not simply a composite of individual functioning systems. All the systems work together. In a similar way, the dynamic physical, social, political, economic, and environmental systems in resilient communities work and function together.

BOX 1.1

Why Effective Community Resilience Is Similar to a Healthy Human Body

Communities can be viewed as a set of interrelated systems that share a common vision, and the overall resilience of communities may be viewed in much the same way as the overall health of the human body. A human body relies on the integrated functioning of its shared systems—like the skeletal, nervous, and immune systems—to maintain health and resist disease and injury. Similarly, communities depend on a number of interrelated systems for economic stability and growth, commerce, education, communication, population wellness, energy, and transportation. The relative “health” of community systems will determine how well a community can withstand disruptive events. If a community has weakened infrastructure, like a human body with a compromised immune system, it will not withstand trauma as well as one in good health.

In both human health and community resilience, investments in maintaining health and building strength reduce the requirement for very expensive treatment and recovery. Health providers now know that prevention is a less expensive pathway than is treatment after the onset of an illness. In the same way, investment in community resilience before a disaster occurs may help a community reduce or avoid monumental recovery and restoration costs after the event has taken place.

When a community has been destroyed by disaster (unlike the human body that has died from disease) it is sometimes possible to bring it back to life. In all cases, though, avoiding destruction in the first place is cheaper, easier, and less traumatic over the long term than resuscitating a devastated community. Post-event mitigation, like remaining free from fatal illness, requires conscious, steady, and organized investment in resilience by those in charge of the care of a community and by the community itself.

This analogy can be extended to the idea that, just like a healthy body is better able to resist disease, a healthy community is better able to prepare for, absorb, and recover from a disaster. For example, infrastructure such as health care with broad access implies a population whose health problems are controlled and/or prevented to the extent possible. A robust health infrastructure enhances resilience, and provides data essential to the early detection of naturally occurring or terrorist-induced epidemics and environmental hazards.

Disaster resilience as an integrated part of community or government decision making is a relatively new concept that is only now being broadly or explicitly adopted through efforts such as Presidential Policy Directive-8 (PPD-8; see below and Chapter 6). Although many efforts have been made to understand disaster resilience and its benefits at various scales (Box 1.2), implementation of approaches to increase disaster resilience in communities has not been consistent nationwide.

The process of building disaster resilience requires continuous assessment, planning, and refinement by communities and all levels of government; resilience is not a task that can be marked as “completed.” No

BOX 1.2

What Is Resilience?

Although resilience with respect to hazards and disasters has been part of the research literature for decades (White and Haas, 1975; Mileti, 1999), the term first gained currency among national governments in 2005 with the adoption of The Hyogo Framework for Action by 168 members of the United Nations to ensure that reducing risks to disasters and building resilience to disasters became priorities for governments and local communities (UNISDR, 2007). The literature has since grown with new definitions of resilience and the entities or systems to which resilience refers (e.g., ecological systems, infrastructure, individuals, economic systems, communities) (Bruneau et al., 2003; Flynn, 2007; Gunderson, 2009; Plodinec, 2009; Rose, 2009; Cutter et al., 2010). Disaster resilience has been described as a process (Norris et al., 2008; Sherrieb et al., 2010), an outcome (Kahan et al., 2009), or both (Cutter et al., 2008), and as a term that can embrace inputs from engineering and the physical, social, and economic sciences (Colten et al., 2008).

perfect end state or end condition of resilience exists. In fact, building resilience means building strong communities that contain adequate essential public and private services including schools, transportation, health care, utilities, roads and bridges, public safety, and businesses. A common understanding of what resilience means for a community, a set of achievable milestones and goals, the approaches for reaching those milestones, and agreed-upon measures of progress are thus required by the people, businesses, and government agencies associated with that community. Resilience also requires that people, businesses, and government agencies recognize their roles and responsibilities, individually and collectively, and act on these roles and responsibilities to help make their communities more resilient. While local and state institutions grapple with specific issues within their communities, for example, federal agencies provide the data, knowledge, tools, and assistance that are needed by all communities to help them become more resilient. A community’s citizens and the private sector also have important roles and responsibilities to increase resilience. These roles and responsibilities, including the data and tools needed to increase resilience, are described in detail later in this report (see also Appendix C).

Enhancing the nation’s resilience to disasters is a national imperative for the stability, progress, and well-being of the nation that can benefit the nation economically, environmentally, and from a national security perspective. However, the challenge of increasing national resilience is profound. These challenges were recognized collectively by eight federal agencies and a community resilience group affiliated with a National Laboratory5 who asked the National Research Council to address the broad issue of increasing national disaster resilience (Box 1.3).

BOX 1.3

Increasing National Resilience to Hazards and Disasters Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee overseen collaboratively by the Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy and the Disasters Roundtable will conduct a study and issue a consensus report that integrates information from the natural, physical, technical, economic, and social sciences to identify ways to increase national resilience to hazards and disasters in the United States. In this context, “national resilience” includes resilience at federal, state, and local community levels. The committee will:

______________

5 The study sponsors (see also Preface) include U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Department of Homeland Security and Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Geological Survey, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory/Community and Regional Resilience Institute.

• Define “national resilience” and frame the primary issues related to increasing national resilience to hazards and disasters in the United States;

• Provide goals, baseline conditions, or performance metrics for resilience at the U.S. national level;

• Describe the state of knowledge about resilience to hazards and disasters in the United States;

• Outline additional information or data and gaps and obstacles to action that need to be addressed in order to increase resilience to hazards and disasters in the United States; and

• Present conclusions and recommendations about what approaches are needed to elevate national resilience to hazards and disasters in the United States.

This report responds to this charge by providing actionable recommendations and guidance on how to increase national resilience from the level of the local community, states, regions, and the nation. Because the nation’s culture has traditionally been focused on responses to emergencies or to specific disaster events rather than on coherent assessment, planning, and evaluation to increase disaster resilience, the report also recognizes the need for a new national framework for a “culture of disaster resilience” that includes:

(1) Public awareness of and responsibility for managing local disaster nsk (Chapter 2);

(2) Establishing the economic and human value of resilience to help encourage long-term commitments to enhancing resilience (Chapter 3);

(3) Tools or metrics for monitoring progress toward resilience and to understand what resilience looks like for different communities (Chapter 4);

(4) Creating local, community capacity, because decisions and the ultimate resilience of our nation derive from the bottom-up community efforts (Chapter 5);

(5) Identifying sound, top-down government policies and practices to build resilience (Chapter 6); and

(6) Identifying and communicating the necessary roles and responsibilities between communities and all levels of government m building resilience. including gaps m and challenges to communications and actions among these actors (Chapter 7).

To make the task more manageable, the committee drew from the extensive literature and understanding about natural disasters, but recognizes that many of the ideas and findings are applicable to other hazards and disasters. Chapters 2, 3, and 4 provide a foundation for understanding resilience in terms of management, data, metrics, and approaches that represent important elements of building resilient communities. Chapters 5, 6, and 7 focus on the people—the communities and governing institutions—who make decisions to manage and

use data, employ metrics, and implement approaches to help increase resilience. Chapter 8 provides the report’s findings and recommendations.

Building and sustaining resilience is everyone’s business. Yet, major social and cultural shifts in governance, civility, and trust in institutions such as government, the mass media, and science create barriers that have to be overcome for the nation to move forward. The federal government has already begun a campaign to improve national resilience. PPD-8 states that, “The Secretary of Homeland Security shall coordinate a comprehensive campaign to build and sustain national preparedness, including public outreach and community-based and private-sector programs to enhance national resilience, the provision of Federal financial assistance, preparedness efforts by the Federal Government, and national research and development efforts” (White House and DHS, 2011). True national resilience will integrate these federal efforts with complementary efforts by state and local government, the private sector, and communities at all scales (see Chapter 6 for further discussion of PPD-8).

Inherent in building the culture of resilience is the ability to incorporate scientific information, data, and observing systems to ensure the availability of reliable information, decision support tools, and data sources to decision makers. Enhancing resilience is achieved through vigorous scientific, technical, and engineering research that enables improved forecasting, better risk and disaster management, the development of metrics for assessing progress toward increased resilience, advances in understanding community dynamics, advances in understanding the economics of insurance and disasters, and improved analysis of the legal and social forces at work in communities. Research is essential to building more resilient communities, and research challenges and needs to improve disaster resilience are presented throughout the report.

The report weaves together different kinds of data and experiences from across the nation, including the committee’s visits and workshops in the Louisiana and Mississippi Gulf Coasts; Cedar Rapids and Iowa City, Iowa; and Southern California (Appendix B). These examples are used to demonstrate ways in which research in physical and social sciences, engineering, and public health have been tested by the experiences of communities and governing bodies (see also NRC, 2011).

The committee also sought public input through the use of a questionnaire made available through listservs and on the study’s Web page.6 In soliciting information on local opinions across the nation on how resilient their communities are, the committee received both identified and anonymous responses. The quotations that start each chapter are an effort to capture just some of the direct, relevant input the committee received from the wide range of contributors to the study from across the nation. The committee felt that these voices, whether or not they were identified by name, provided thoughtful

______________

6http://sites.nationalacademies.org/PGA/COSEPUP/nationalresilience/index.htm.

indications of the broad interest in resilience across the country as well as some of its profound challenges.

ON THE NATION’S RESILIENCE AGENDA

This report is viewed as a first step in establishing a vision and national framework for resilience. Fostering a culture of community resilience is viewed as a principal goal for the nation. Building or enhancing resilience at the national level is a long-term process, and it is expected that the tools and framework presented in this report will provide a structure for additional work across communities, including the private sector, and all government levels to advance, measure, and realize resilience in the United States. Enhancing the nation’s resilience to disasters will be socially and culturally difficult and politically challenging, and will require certain investments, but the attendant rewards are a safer, healthier, more secure, and prosperous nation. The committee hopes that this report will provide a pathway for achieving this vision for the nation and its communities.

Bruneau, M., S. E. Chang, R. T. Eguchi, G. C. Lee, T. D. O’Rourke, A. M. Reinhorn, M. Shinozuka, K. Tierney, W. W. Wallace, and D. von Winterfeldt. 2003. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthquake Spectra 19(4):733-752.

Colten, C. E., R. W. Kates, and S. B. Laska. 2008. Three years after Katrina: Lessons for community resilience. Environment 50(5):36-47.

Cutter, S. L., L. Barnes, M. Berry, C. Burton, E. Evans, E. Tate, and J. Webb. 2008. A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Global Environmental Change 18:598-606.

Cutter, S. L., C. G. Burton, C. T. Emrich. 2010. Disaster resilience indicators for benchmarking baseline conditions, Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 7(1), Article 51.

DHS Risk Steering Committee. 2008. DHS Risk Lexicon. Department of Homeland Security. Available at www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/dhs_risk_lexicon.pdf.

Flynn, S. 2007. The Edge of Disaster: Rebuilding a Resilient Nation. New York: Random House.

Gunderson, L. 2009. Comparing Ecological and Human Community Resilience. Research Report 5. Community and Regional Resilience Initiative, Oak Ridge, TN. Available at http://resilientus.org/library/Final_Gunderson_1-12-09_1231774754.pdf.

Kahan, J. H., A. C. Allen, and J. K. George. 2009. An operational framework for resilience. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 6(1), Article 83. Available at: http://www.bepress.com/jhsem/vol6/iss1/83/.

Mileti, D. 1999. Disasters by Design: A Reassessment of Natural Hazards in the United States. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press.

Multihazard Mitigation Council. 2005. Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: An Independent Study to Assess the Future Savings from Mitigation Activities, Vol. 1, Findings, Conclusions, and Recommendations. Washington, DC: National Institute of Building Sciences. Available at ww.nibs.org/MMC/MitigationSavingsReport/Part1_final.pdf.

NCDC (National Climatic Data Center). 2012. Billion Dollar U.S. Weather/Climate Disasters. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Available at http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/reports/billionz.html.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2011. NWS Central Region Service Assessment: Joplin, Missouri, Tornado—May 22, 2011. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Weather Service, Central Region Headquarters, Kansas City, MO. Available at http://www.nws.noaa.gov/os/assessments/pdfs/Joplin_tornado.pdf.

Norris, F. H., S. P. Stevens, B. Pfefferbaum, K. F. Wyche, and R. L. Pfefferbaum. 2008. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology 41:127-150.

NRC (National Research Council). 2011. National Earthquake Resilience: Research, Implementation, and Outreach. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2012. Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Plodinec, M. J. 2009, Definitions of Resilience: An Analysis. Community and Regional Resilience Initiative, Oak Ridge, TN. Available at http://www.resilientus.org/library/CARRI_Definitions_Dec_2009_1262802355.pdf.

Rose, A. 2009. Economic Resilience to Disasters. CARRI Research Report 8. Community and Regional Resilience Initiative, Oak Ridge, TN. Available at http://www.resilientus.org/library/Research_Report_8_Rose_1258138606.pdf.

Rose, A., and S. B. Blomberg. 2010. Total economic impacts of a terrorist attack: Insights from 9/11. Peace Economics, Peace Science, and Public Policy 16(1), Article 2.

Sherrieb, K., F. H. Norris, and S. Galea. 2010. Measuring capacities for community resilience. Social Indicators Research, doi10.1007/s11205-010-9576-9.

SDR (Subcommittee on Disaster Reduction). 2005. Grand Challenges for Disaster Reduction. Washington, DC: National Science and Technology Council.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction Secretariat). 2007. Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. Geneva, Switzerland: UN/ISDR. Available at http://www.unisdr.org/files/1037_hyogoframeworkforactionenglish.pdf.

UNISDR. 2011. Terminology. Available at www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology.

White, G. F., and J. E. Haas. 1975. Assessment of Research on Natural Hazards. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

White House and DHS (Department of Homeland Security). 2011. Presidential Policy Directive-8. Available at http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/presidential-policy-directive-8-national-preparedness.pdf.