“Resilience begins with leadership, appropriate planning both in terms of action-plans but also in terms of proper community planning and development visions.”

Dr. Larry Weber, University of Iowa

6

The Landscape of Resilience Policy—

Resilience from the Top Down

The key elements of resilience include strong governance at all levels, including the making of consistent and complementary local, state, and federal policies. As previously discussed, communities are not under a single authority, but must function under a mix of policies and practices implemented and enforced by different levels of government. Furthermore, policies that make the nation more resilient are important in every aspect of American life and economy, and not just during times of stress or trauma. A key role of policies designed to improve national resilience is to take the long-term view of community resilience and to help avoid short-term expediencies that can diminish resilience. Policies to improve community and national resilience may be designed and promulgated specifically to address issues of resilience, or they may be policies designed for another reason that acknowledge the importance and process of building resilience. In some cases, policies designed to accomplish one positive goal may unintentionally cause deterioration of community resilience. Therefore, policies and programs at all levels of government require examination to assess their impact on the long-term resilience of communities and the nation.

Increasing national resilience through specific policy measures involves addressing the multiple aspects of resilience that have been discussed in this report. For example, as Chapter 2 emphasizes, policy mechanisms play a role in risk management through provision of data and information to evaluate potential hazards, although, as Chapter 2 outlined, information alone does not ensure resilience. Likewise, progress toward improved resilience is driven by the need and value propositions outlined in Chapter 3, and likely monitored using the indicators and tools described in Chapter 4 of this report. At the national level, policies that enhance national resilience are not simply disaster reduction policies. Because the scope of resilience is sometimes not fully appreciated,

some who contemplate national resilience policy think first of the Stafford Act and its role in disaster response and recovery. Although the Stafford Act (discussed further below) does provide for certain responsibilities and actions in the face of a disaster, national resilience, as has been demonstrated throughout this report, transcends the immediate impact and disaster response and, therefore, grows from a broader set of policies. Many of the policies that affect national resilience are not related to specific hazards or disaster events at all, including some policies that may apply only to specific subsystems of a community (Longstaff et al., 2010), and others that may have effects on essential community services such as education and health care (see Chapter 5).

With this background, this chapter is developed from the idea that improvement of national resilience relies on collections of coordinated and integrated policies at multiple levels rather than a single comprehensive government policy. The subsequent sections provide context for considering policy options across the full range of stakeholders and authorities that constitute the landscape of resilience, and describes several current practices at federal, state, and local levels that support resilience, as well as policies that unintentionally undermine resilience. Identification of specific roles and responsibilities of government in building resilience flows naturally from discussion in Chapter 5 of the complementary roles and actions that communities can embrace as part of a systemic national effort to increase resilience. The interdependency and interaction of community initiatives and government policy are critical for increasing resilience (see Chapter 7 for the way in which bottom-up and top-down approaches may be linked).

EXISTING FEDERAL POLICIES THAT STRENGTHEN RESILIENCE

Federal policies are intended to provide a set of nationally uniform laws or practices to address national needs that transcend the conditions or needs of individual states or cities. Federal policies address issues that have national scope and importance, even if the issues and consequences are local. These policies exist at the level of the Executive Branch—in both the Office of the President and in the Cabinet Departments as well as in independent federal agencies—and in laws enacted by the Legislative Branch. An outline of the most critical of the policies that the committee determined would provide support to strengthen resilience is briefly reviewed below.

Federal Executive Branch Policies Supporting Resilience

U.S. national leaders continue to seek broad policies for strengthening the nation against both terrorist acts and natural disasters. Certain Executive Branch policies, for example, are promulgated by the President through Executive Orders or Directives that guide the actions of federal agencies. These Presidential Directives and Executive Orders have the force of law. Directives

may take different forms, but most recent Presidential Directives affecting national resilience have been either Homeland Security Presidential Directives (HSPD) or Presidential Policy Directives (PPD). A Presidential Policy Directive (PPD-8) from 2011 entitled “National Preparedness” begins by saying:

This directive is aimed at strengthening the security and resilience of the United States through systematic preparation for the threats that pose the greatest risk to the security of the Nation, including acts of terrorism, cyberattacks, pandemics, and catastrophic natural disasters. (White House and DHS, 2011)

The Directive calls for the development of a National Preparedness System to guide activities that will enable the nation to achieve the goal of strengthening its security and resilience; for a comprehensive campaign to build and sustain national preparedness; and for an annual National Preparedness Report to measure progress in meeting the goal. Importantly, the President calls on DHS to embrace systematic preparation against all types of threats, including catastrophic natural disasters.

Preparedness is not synonymous with resilience, but they are related. According to PPD-8, “The term ‘resilience’ refers to the ability to adapt to changing conditions and withstand and rapidly recover from disruption due to emergencies” (White House and DHS, 2011). This definition is in keeping with the definition of resilience established by the committee during the course of this study (see Chapter 1). The Directive also recognizes resilience as a characteristic of an individual, community, or nation and that resilience is enhanced through improved preparedness as noted below:

The Secretary of Homeland Security shall coordinate a comprehensive campaign to build and sustain national preparedness, including public outreach and community-based and private-sector programs to enhance national resilience, the provision of Federal financial assistance, preparedness efforts by the Federal Government, and national research and development efforts. (White House and DHS, 2011)

As Box 6.1 shows, an entire series of HSPDs has been issued since September 11, 2001. Although many of these directives are heavily focused on terrorist threats, the preparation and response of communities to terrorist threats contain many of the same elements as preparation for natural hazards. Thus, significant and deliberate overlap exists in the application of HSPDs to both human-made and natural threats. PPD-8 is one that can be broadly applied in this way.

Importantly, PPD-8 recognizes that our national response to a wide range of events, from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic to the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill, has been strengthened by leveraging the expertise and resources that exist in our communities. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is directed to coordinate a “comprehensive campaign,” informed by the long-term requirements for national resilience, to reach the goals of the Directive. Although the President assigns the Secretary of DHS to coordinate this comprehensive campaign under PPD-8, the directive indicates that DHS is not expected to conduct all of the work itself, but to coordinate the work of others. The Committee supports the role of DHS in serving as coordinator of these broad efforts to enhance national resilience under PPD-8 (see additional discussion in Chapter 7).

BOX 6.1

Homeland Security Presidential Directives Relevant to National Resilience

• HSPD-1: Organization and Operation of the Homeland Security Council. Ensures coordination of all homeland security-related activities among executive departments and agencies and promotes the effective development and implementation of all homeland security policies (October 2001).

• HSPD-3: Homeland Security Advisory System. Establishes a comprehensive and effective means to disseminate information regarding the risk of terrorist acts to federal, state, and local authorities and to the American people (March 2002). This system was replaced by the Terrorism Advisory System in 2011.

• HSPD-5: Management of Domestic Incidents. Enhances the ability of the United States to manage domestic incidents by establishing a single, comprehensive national incident management system (February 2003).

• HSPD-7: Critical Infrastructure Identification, Prioritization, and Protection. Establishes a national policy for federal departments and agencies to identify and prioritize U.S. critical infrastructure and key resources and to protect them from terrorist attacks (December 2003).

• HSPD-8 Annex 1: National Planning. Rescinded by PPD-8 (below): National Preparedness, except for paragraph 44. Individual plans developed under HSPD-8 and Annex I remain in effect until rescinded or otherwise replaced (December 2003).

• Presidential Policy Directive/PPD-8: National Preparedness. Aimed at strengthening the security and resilience of the United States through systematic preparation for the threats that pose the greatest risk to the security of the nation, including acts of terrorism, cyber attacks, pandemics, and catastrophic natural disasters (March 2011).

• HSPD-20: National Continuity Policy. Establishes a comprehensive national policy on the continuity of federal government structures and operations and a single national continuity coordinator responsible for coordinating the development and implementation of federal continuity policies (May 2007).

• HSPD-20 Annex A: Continuity Planning. Assigns executive departments and agencies to a category commensurate with their COOP/COG/ECG responsibilities during an emergency (September 2008).

• HSPD-21: Public Health and Medical Preparedness. Establishes a national strategy that will enable a level of public health and medical preparedness sufficient to address a range of possible disasters (October 2007).

• HSPD-23: National Cyber Security Initiative (January 2008).

Source: DHS, http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/editorial_0607.shtm.

Notes: PPD-8 (http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/gc_1215444247124.shtm) replaces HSPD-8 (2003) and HSPD-8 Annex I (2007). Relevance of all HSPDs in this list to national resilience has been evaluated by the Committee for this study.

The language of PPD-8 makes clear that American communities and the private sector play central roles in enhancing national resilience and, therefore, that DHS’s coordination of federal efforts also involves effective engagement of those critical stakeholders. Significantly, DHS is also called upon to coordinate federal financial assistance, the preparedness efforts by other federal agencies, and national research and development efforts.

The issuance of PPD-8 was a significant advance in increasing and improving the federal role in national resilience, and its goals were amplified by the report of the Homeland Security Advisory Council’s Community Resilience Task Force (CRTF, 2011). That report, released in June 2011, builds on the Quadrennial Homeland Security Review Report1 and contains a set of recommendations intended to define the role of DHS in advancing national resilience through the mechanism of PPD-8:

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) clearly has an important role to play in building national resilience, but at its core, the resilience charge is about enabling and mobilizing American communities. The CRTF acknowledges that many relevant activities are already underway, particularly in fostering development of preparedness capabilities, but observes that those activities are rarely linked explicitly to resilience. (CRTF, 2011)

______________

1The Quadrennial Homeland Security Review Report (http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/qhsr_report.pdf) contains five Homeland Security missions. Mission 5 is Resilience to Natural Disasters, which outlines the traditional elements of hazard mitigation, enhanced preparedness, effective emergency response, and rapid recovery. These issues are also discussed in the DHS Bottom-Up Review Report (http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/bur_bottom_up_review.pdf) released in July, 2010.

The recommendations contained in the CRTF report (Box 6.2) represent a strong and clear starting point for federal involvement in building national resilience. The recommendations are directed specifically to DHS and call for clarification of responsibilities, building knowledge and public awareness to enhance individual and societal resilience, and providing long-term targets to support urban planning and the built environment.

BOX 6.2

Recommendations of the Homeland Security Advisory Council, Community Resilience Task Force (CRTF) 2011

CRTF Recommendations that apply across the full range of Community Resilience activities include:

CRTF Recommendation 1.1: Build a Shared Understanding of the Shared Responsibility. DHS should take the lead in working with key stakeholder groups to develop and share models for resilience—illustrations of resilience in operational settings—within the context of each group. The purpose is to motivate stakeholders to learn from each other and to do what they can to enhance resilience without waiting for external intervention.

CRTF Recommendation 1.2:Build a Coherent and Synergistic Campaign to Strengthen and Sustain National Resilience. DHS should align policies, programs, and investments to motivate and operationalize resilience, and should use its leadership charge from PPD-8 to motivate similar actions across the federal government and throughout the Nation.

CRTF Recommendations 1.3: Organize for Effective Execution. DHS should establish a National Resilience Office and charge it with building the resilience foundation envisioned by the QHSR.

CRTF Recommendation 1.4: Build the Knowledge and Talent Base for Resilience. DHS should implement a research program to build the intellectual underpinnings for resilience training and education programs to be delivered throughout the Nation.

CRTF Recommendations related to enhancing individual and societal resilience include:

CRTF Recommendation 2.1:Update ready.gov. DHS should establish and execute a plan for periodic review and update of the content and presentation of information on ready.gov; messages should be linked explicitly to resilience outcomes.

CRTF Recommendation 2.2:Build Public Awareness. DHS should develop and implement a comprehensive and coherent suite of communications strategies in support of a national campaign to increase public awareness and motivate individual citizens to build societal resilience.

CRTF Recommendation 2.3: Motivate and Enable Action. DHS should adapt and implement proven incentive and award programs to motivate individual and community engagement and action, and further develop mechanisms to facilitate and enable engagement.

CRTF Recommendations targeting urban planning for the built environment include:

CRTF Recommendation 3.1: Leverage Existing Federal Assets. DHS, in conjunction with the General Services Administration and local officials, should develop a Resilient Community Initiative (RCI) that leverages federal assets and programs to enable community resilience.

CRTF Recommendation 3.2: Align Federal Grant Programs to Promote and Enable Resilience Initiatives. DHS should review and align all grant programs related to infrastructure or capacity building, and should support development of synchronized strategic master plans for improvement of operational resilience throughout the Nation.

CRTF Recommendation 3.3: Enable Community-Based Resilient Infrastructure Initiatives. DHS should transform its critical infrastructure planning approach to more effectively enable and facilitate communities in their efforts to build and sustain resilient critical infrastructures. CRTF Recommendation 3.4: Enable Community-Based Resilience Assessment. DHS should coordinate development of a community-based, all-hazards American Resilience Assessment (ARA) methodology and toolkit.

Source: Homeland Security Advisory Council, Community Resilience Task Force (http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/hsac-community-resilience-task-force-recommendations-072011.pdf), June 2011.

In addition to the CRTF recommendations, the National Preparedness Goal developed by DHS in response to PPD-8 provides a statement of national preparedness that includes preemptive actions designed to mitigate or reduce the impact of both terrorism and natural hazards in order to develop a more resilient nation (Box 6.3). The National Preparedness Goal deals with preparedness across jurisdictions and at a national scale.

The formulation of the National Preparedness Goal, the operational implementation of its many aspects, and the administration of several community funding programs, primarily through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA),2 place DHS in a strong position to provide leadership in the interagency efforts required to build national resilience.

______________

2http://www.dhs.gov/ynews/releases/20110217-dhs-fy12-grant-guidance.shtm.

BOX 6.3

DHS National Preparedness Goal (excerpt)

“We describe our security and resilience posture through the core capabilities… that are necessary to deal with great risks, and we will use an integrated, layered, and all-of-Nation approach as our foundation. We define success as:

A secure and resilient Nation with the capabilities required across the whole community to prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from the threats and hazards that pose the greatest risk.

Using the core capabilities, we achieve the National Preparedness Goal by:

— Preventing, avoiding, or stopping a threatened or an actual act of terrorism. — Protecting our citizens, residents, visitors, and assets against the greatest threats and hazards in a manner that allows our interests, aspirations, and way of life to thrive.

— Mitigating the loss of life and property by lessening the impact of future disasters.

— Responding quickly to save lives, protect property and the environment, and meet basic human needs in the aftermath of a catastrophic incident.

— Recovering through a focus on the timely restoration, strengthening, and revitalization of infrastructure, housing, and a sustainable economy, as well as the health, social, cultural, historic, and environmental fabric of communities affected by a catastrophic incident.

…These are not targets for any single jurisdiction or agency; achieving these targets will require a national effort involving the whole community.”

Source: Department of Homeland Security, National Preparedness Goal, 1st Edition, September, 2011, http://www.fema.gov/pdf/prepared/npg.pdf.

The conduct of federal activities in partnership with state, local, and private partners may also be the goal of other Presidential directives. For example, the interaction of federal agencies with the private sector to advance the goal of improving resilience has been demonstrated in the area of critical infrastructure. Homeland Security Presidential Directive 7 (HSPD-7) gives the Secretary of Homeland Security oversight responsibility for protecting 18 critical infrastructure sectors, and gives selected agencies and the Environmental Protection Agency the ability to direct national infrastructure protection for some sectors (Box 6.4). These responsibilities require close coordination with state and local government, as well as the private sector, and may provide a model for the federal—state—local—private partnerships required to develop broader strategies for building resilience in U.S. communities.

BOX 6.4

Roles and Responsibilities of Sector-Specific Federal Agencies in Critical Infrastructure Protection

“18. Recognizing that each infrastructure sector possesses its own unique characteristics and operating models, there are designated Sector-Specific Agencies, including

a. Department of Agriculture—agriculture, food (meat, poultry, egg products);

b. Health and Human Services—public health, health care, and food (other than meat, poultry, egg products);

c. Environmental Protection Agency—drinking water and water treatment systems;

d. Department of Energy—energy, including the production refining, storage, and distribution of oil and gas, and electric power except for commercial nuclear power facilities;

e. Department of the Treasury—banking and finance;

f. Department of the Interior—national monuments and icons; and

g. Department of Defense—defense industrial base.

19. In accordance with guidance provided by the Secretary, Sector-Specific Agencies shall:

a. collaborate with all relevant Federal departments and agencies, State and local governments, and the private sector, including with key persons and entities in their infrastructure sector;

b. conduct or facilitate vulnerability assessments of the sector; and

c. encourage risk management strategies to protect against and mitigate the effects of attacks against critical infrastructure and key resources.”

Source: Homeland Security Presidential Directive 7: Critical Infrastructure Identification, Prioritization, and Protection, December 17, 2003.

Other types of federal policies may also strongly affect resilience in very broad ways. For example, evidence is growing that changing global climate is increasing the nation’s exposure to natural hazards through more frequent and severe storms, as well as more extensive droughts and increased vulnerability of our coastal regions through sea-level rise (NRC, 2012). Thus, one type of long-term federal policy goal to improve U.S. national resilience might include an energy policy that addresses carbon emissions and dependence on imported energy resources. Addressing carbon emissions could help mitigate climate change which otherwise may result in an increase in frequency and intensity of weather-related hazards and could help support a national effort to

become less import-dependent for our energy needs (NRC, 2010). Although such policies may not be recognized immediately as affecting resilience to natural disasters, they are examples of the far-reaching implications of policy decisions that may have impact on national resilience.

Finally, strategic investment of federal funds in local communities— even within the structure of existing statutes and programs—may provide a strong impetus to develop more resilient communities. Communities realize that stronger infrastructure and institutions would make their population less vulnerable to disasters, but they generally lack the resources or political will to make capital-intense short-term investments even if they believe that those investments will reap long-term benefits. In the future, predisaster funding may serve as a critical tool in building national resilience. The practice of federal funding of post-disaster recovery within local communities should be strategically complemented with predisaster funding of the highest-priority resilience elements within a community, such as enforcement of building codes, land-use and development planning, and disaster-resistant health care services. Existing programs such as those within FEMA3 could be strengthened to place a greater emphasis on resilience. Careful analysis and consideration of a strategic approach to federal funding of resilience are important in efforts to reduce the impact (and cost) of disasters.

Coordination of Executive Branch Federal Agencies

In addition to the Executive Branch policies issued through Presidential Directives and Executive Orders, agency policies may be initiated by individual federal agencies through the rulemaking process, and may include such things as management practices for federal lands or other resources, or rules and policies that outline roles and responsibilities of various federal agencies in managing federal assets, including those directing or supporting the activities that foster community resilience. A key challenge for the federal government is how to maintain motivation and accountability among all of the federal agencies in the pursuit of defined, common goals toward increasing resilience. Each federal agency has a specific mission, has a budget that is largely separate from the budgets of other agencies, and is accountable to the President and to Congress, rather than to other agencies.

A large number of federal agencies play key roles in mitigation, preparedness and response aspects of building resilience. The ways in which federal agencies are coordinated to address resilience issues on individual, community, state, and national levels are currently not always clear, and the process of coordination should be defined around a common vision of resilience in order to leverage the effectiveness of each agency’s efforts and investments. DHS, by virtue of its mission and because it contains the major response

______________

agencies, FEMA and the Coast Guard, houses much of the federal responsibility and accountability for fostering national resilience and has a leading role during response to incidents. However, DHS partners with other agencies that provide research, information, and response capabilities essential to national resilience. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the U.S. Forest Service, and the the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers play crucial roles in providing scientific understanding and real-time assessments of weather-related issues, fires, earthquakes, floods, tornadoes, and other natural hazards, relevant both for short- and long-term monitoring and planning before disasters occur and during actual events. The Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Reclamation, the National Resources Conservation Service, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission manage or provide oversight for levees and other structures and therefore play a critical role in flood reduction and management, water supply, and energy generation. The Department of Energy has key responsibilities for the energy infrastructure—coordinating such aspects as energy infrastructure security and energy restoration, and emergency preparedness and response for critical energy infrastructure.

In addition to attention to natural science and infrastructure components, resilience relies on the health and welfare of the citizenry, and so federal agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Education, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and other federal agencies play key roles in helping to build the total resilience of U.S. communities. A partial list of the numerous federal departments and agencies engaged in some aspect of building community and national resilience is shown in Table 6.1 along with some of their ongoing resilience-related activities and initiatives. Of course it is difficult to coordinate these numerous and diverse federal efforts, but failure to adequately harmonize the work of these agencies reduces the effectiveness of the overall federal effort to increase national resilience. On the other hand, improved coordination of federal resilience programs in communities provides significant opportunities for leveraging federal funding and ensuring that agencies are not working at cross purposes.

Many agencies have demonstrated successful federal—state—local— private cooperation arising from internal agency vision or goals, For example, USGS and NOAA have worked with nonfederal partners to transfer research results to their stakeholders, and have worked successfully to help communities to assess and mitigate their earthquake and coastal hazards. These successful examples have not happened by accident, but result from explicit policies within each agency. The vision statement from the NOAA Administrator in the agency’s 5-year plan says:

NOAA’s mission is central to many of today’s greatest challenges. The state of the economy. Jobs. Climate Change. Severe weather. Ocean acidification. Natural and human-

induced disasters. Declining biodiversity. Threatened or degraded oceans and coasts. These challenges convey a common message: Human health, prosperity, and well-being depend upon the health and resilience of both managed and unmanaged ecosystems. Combined with the capabilities of our many partners in government, universities, and private and nonprofit sectors, NOAA’s science, service, and stewardship capabilities can help transition to a future where societies and world’s ecosystems reinforce each other and are mutually resilient in the face of sudden and prolonged change. (NOAA, 2012)

And the USGS states:

The USGS brings the results of its many research programs together to create knowledge that is understandable, useable, and accessible in many forms—including statistics, reports, analyses, maps, models, and tools that forecast the consequences of various choices. These products, often created in partnership with other governmental, academic, and private organizations, provide the basis for evaluating the effectiveness of specific policies and management actions, and they are essential to the success of policymakers and decisionmakers at local, State, Federal, tribal, and international levels. (USGS, 2009)

Despite the intent behind written statements such as the examples above, coordination of federal agencies’ efforts to promote and build national resilience will be difficult owing to the independence of federal agencies, each with its own mission and budget and each emphasizing disaster planning, homeland security, or resilience to different degrees. However, no consistently owned and applied vision for national resilience can exist without coordination of federal agencies. Interagency coordination is essential to a number of other federal efforts, and many interagency coordination groups already exist with varying degrees of effectiveness. To work effectively and to ensure participation by all key agencies, such an interagency working group would necessarily be convened or created and charged by the Executive Office or Congress. Coordinating investments among federal agencies is exceedingly difficult, but a common vision of national resilience developed with the participation of all key federal agencies, and with input from state, local, and private-sector stakeholders would improve the consistency with which those funds are applied.

As discussed above, PPD-8 provides clear presidential direction for coordination of federal efforts to enhance national resilience, and coordination of policies and procedures among federal agencies are further discussed in Chapter 7.

TABLE 6.1 Examples of Federal Efforts Among the Study’s Sponsors and Other Federal Agencies That Contribute to Enhanced Disaster Resilience

| Federal Departments and Agencies | Ongoing or Planned Goal. Program, Project, or Initiative | Web Link |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) |

Goals 1 and 2 of USDA Strategic Plan 2010-2015: 1) Assist rural communities, including expansion of USDA “work with landowners to increase adoption of practices that will make farms, ranches, and forest lands more resilient to the effects of climate change.” (p. 3) 2) “Ensure that our national forests and private working lands are conserved, restored, and made more resilient to climate change, while enhancing our water resources.” (P-14) |

http://www.ocfo.usda.gov/usdasp/ sp2010/sp2010.pdf (in addition to the U.S. Forest Service, other offices in the USDA with resilience-oriented initiatives include the National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the Agricultural Research Service |

| U.S. Forest Service | National Roadmap for Responding to Climate Change, including a Performance Scorecard: The Roadmap describes agency response to climate change through “adaptive restoration-by restoring the functions and processes characteristic of healthy, resilient ecosystems” (p. 18). The Scorecard includes elements about organization, leadership, partnerships, adaptation, mitigation, and sustainability. | (1) http://www.fs.fed.us/climatechange/ pdf/Roadmapfinal.pdf (2) http://www.fs.fed.us/climatechange/ advisor/scorecard.html |

| U.S. Department of Commerce | |||

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | National Ocean Service/Coastal Services Center and Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management. Coastal resilience initiatives to allow communities to “bounce back” after a disaster; programs, data, tools, analysis, projects, and training allow users (coastal management community) access to information important for coastal resilience. A guide to coastal community resilience outlines coastal hazards, the importance of coastal resilience, and steps for coastal communities to take to become more resilient and to assess progress. NOAA and Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium: Coastal Resiliency Index: A community self-assessment aims to provide community leaders with straightforward, inexpensive ways to gauge whether their community will return to a satisfactory level of functioning after a disaster; in other words, to allow communities to measure their progress toward becoming disaster resilient. (Link 4) Disaster Resilient Communities: A NIST/NOAA Partnership: See description under National Institute of Standards and Technology, below. (Link 5) National Weather Service: Provides local and regional data and forecasts regarding weather situations (e.g.. storms. hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, tsunamis) (Links 6. 7) |

(1) http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ resilience.html (2) http://www.csc.noaa.gov/psc/ riskmgmt/resilience.html (3) http://www.crc.uri.edu/download/ CCRGuide_lowres.pdf (4) http://masgc.org/page.asp?id=591 (5) http://fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/ build07/PDF/b07037.pdf (6) http://www.nws.noaa.gov/ (7) http://www.nws.noaa.gov/com/ weatherreadynation/ |

TABLE 6.1 Examples of Federal Efforts Among the Study’s Sponsors and Other Federal Agencies That Contribute to Enhanced Disaster Resilience

| Federal Departments and Agencies | Ongoing or Planned Goal. Program, Project, or Initiative | Web Link |

| Engineering Laboratory | Disaster-resilient buildings, infrastructure, and communities: Developing and applying measurement methods, models, and tools to reduce risk and increase resilience of buildings, infrastructure, and communities. Related areas include earthquake and fire risk reduction for buildings and communities, windstorm impact reduction, and behavior of structures under multihazard situations. | http://www.nist.gov/el/disresgoal.cfm |

| U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) | Defense Critical Infrastructure Program (DCIP): DOD role described in the overarching document Homeland Security Presidential Directive 7 | HSPD-7: http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/ editorial_0607.shtm (in addition to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, other elements of the DOD involved directly in resilience-related activities include the National Guard Bureau and the U.S. Northern Command) |

| U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) | Public works defense infrastructure (related to the DCIP): Critical infrastructure protection and resilience. All-hazards approach. Has involved several regional resilience studies of dams and watersheds. Civil works: flood damage reduction, water and power supply, |

(1) http://www.dtic.mil/ndia/ 2010homeland/Seda_Sanabria.pdf (2) http://www.usace.army.mil/ Locations.aspx (3) |

| regulatory program (for U.S. waters), and protection of resources. District offices with direct responsibility and oversight. (Link 2) Emergency response (includes disaster response, flood control and coastal emergencies, emergency support Responds in several ways as part of federal government’s unified national response to disasters; activities include providing engineering expertise to local and state governments, providing essential resources such as drinking water, auxiliary power, temporary housing and roofing, making repairs to critical infrastructure. Emergency support function assists other federal agencies, particularly DHS and FEMA, and is performed in concert with federal, state, and local governments, contractors, and industries. Supports DHS disaster response framework. (Link 3) |

http://www.usace.army.mil/Media/FactSheets/FactSheetArticleView/tabid/219/Article/156/emergency-response.aspx | |

| U.S. Navy | The U.S. Navy Climate Change Roadmap addresses the national security issues associated with climate change. The roadmap presents the ways in which the U.S. Navy will observe, predict, and adapt to climate change. | http://www.navy.mil/navydata/documents/CCR.pdf |

| U.S. Department of Energy | ||

| Office of Infrastructure Security and Energy Restoration | Coordinates DOE’s response to energy emergencies, contributes to the security of the national energy infrastructure, aids local and state governments with planning, preparation, and response to energy emergencies | http://energy.gov/oe/mission/infrastructure-security-and-energy-restoration-iser |

| U.S. Department of Energy | ||

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Health protection agency for the nation: works to protect people from public health threats, including bioterrorism, chemical and radiation emergencies, disease outbreaks, and medical emergencies arising from natural disasters. CDC’s Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response leads the agency’s preparedness and response activities by providing strategic direction, support, and coordination for activities across CDC as well as with local, state, tribal, national, territorial, and international public health partners. CDC provides funding and technical assistance to states to build and strengthen public health capabilities. Ensuring that states can adequately respond to threats will result in sreater health security. | http://www.cdc.gov/ http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/http:// emergency.cdc.gov/ |

| Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) | National and community preparation to respond to and recover from public health and medical disasters and emergencies. Key goals include promoting resilient communities, strengthening federal public health and medical leadership- promoting effective countermeasures, improving health care delivery systems, strengthening ASPR leadership and management. Office of Preparedness and Emergency Operations under ASPR has responsibility for operational plans, tools, and training to ensure response and recovery from health and medical emergencies. Coordinates with other federal asencies during | http://www.phe.gov/about/aspr /strategic-plan/Pages/default.aspx |

| Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology | Tasked with creating a national database and a plan for “the utilization of an electronic health record (EHR) for each person in the United States by 2014.” These records can allow access to key medical data for those affected by disasters who are in need of treatment and medications. | http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/ server.pt/community/healthit_hhs_ gov__home/1204 |

| U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) | DHS works to build a resilient nation. The agency provides the coordinated federal response to events such as terrorist attacks, natural disasters or other large-scale emergencies. DHS also works with federal, state, local and private sector partners in recovery efforts. | http://www.dhs.gov/building- resilient-nation |

| Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) | FEMA supports the public and first responders to prepare for. protect against, respond to. recover from, and mitigate all hazards, FEMA’s statutory authority derives from the Stafford Act (P.L. 100-707) (Link 1) Guiding documents and plans include the National Response Framework (Link 2), a “Whole Community” operational approach (Link 3), and a National Disaster Recovery Framework (Link 4). | (1) http://www.fema.gov/about /index.shtm (2) http://www.fema.gov/ emergency/nrf/ (3) http://www.fema.gov/about/ wholecommunity.shtm (4) http://www.fema.gov/national -disaster-recovery-framework |

| Science and Technology Directorate | Manages science and technology research for homeland protection, including development and transition for use by first responders. Research includes physical and engineering science as well as human factors and behavioral science. | http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/struc ture/editorial_0530.shtm |

| U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development |

| Community Planning and Development Program | The office works to develop viable communities that provide opportunities for low- and moderate-income people through a variety of public-private partnerships. Aspects of these efforts include affordable housing as well as community and economic development. | http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD? src=/program_offices/comm_planning |

| Office of Public and Indian Housing | The office focuses on safe, affordable housing including creation of possibilities for residents to become self-sufficient and economically stable (Link 1). The Capital Fund Emergency’Natural Disaster Funding is a financial reserve for public housing agencies (PHAs) that experience emergency situations or a natural disaster subject to compliance with certain requirements (Link 2). | (1) http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/ HUD?src=/program_offices/public_ indian_housing (2) http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/ HUD?src=/program_offices/public _indian_housing/programs/ph/ capfund/emfunding |

| U.S. Department of the Interior | ||

| U.S. Geological Survey | Primary earth science organization in the Department of the Interior. As part of the agency’s purview over processes operating in the Earth science system, it includes a specific focus on monitoring and assessing natural hazards and helping to develop strategies for resilience. | http://www.usgs.gov/natural_hazards/; http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2011/3008/ |

| Independent Agencies and Corporations: | ||

| National Aeronautics and Space Administration | ||

| Applied Sciences Program | The program uses Earth science data derived from NASA | http://www.coastal.ssc.nasa.gov/ |

| Program | research to address a variety of topics including coastal community resilience. | |

| Oak Ridge Niirional Laboratory (ORNL)/Community and Regional Resilience Institute (CARRI) | Originally housed at the ORNL, CARRI is now housed at the Meridian Institute. The CARRI mission aims to help develop and share information and guidance that communities may use to prepare for. respond to. and rapidly recover froin human-made or natural disasters with minimal downtime of basic services. | http://www.resilientus.org/ |

Federal Legislation

Communities across the nation rely on federal policies that help advance resilience. Congress and other policymakers can improve the resilience of communities and the nation by taking a holistic view of the diverse aspects of community resilience when developing policies of all kinds as well as recognizing the complex interactions of specific federal policies with each other and their likely effect on the communities themselves.

Legislative Branch policies may be established and implemented explicitly through legislation, or implicitly through the oversight process that holds federal agencies accountable through the hearings or appropriations processes. Major existing legislative policies or actions that contribute to resilience are numerous and varied. Two foundational laws are the Stafford Act4 and the Homeland Security Act of 20025. These statutes provide most of the organizational and functional framework for mitigating, responding to, and recovering from natural disasters and acts of terrorism.

The most widely known law, and the most widely cited in the context of traumatic incidents, is the Stafford Act. The Stafford Act is intended:

to provide an orderly and continuing means of assistance by the Federal Government to State and local governments in carrying out their responsibilities to alleviate the suffering and damage which result from such disasters…6

Therefore, the Stafford Act is primarily a guide for responding to disaster incidents and does not refer explicitly to resilience.

Another piece of legislation, passed into law as The Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-390), amended the Stafford Act:

(1) to reduce the loss of life and property, human suffering, economic disruption, and disaster assistance costs resulting from natural disasters; and

(2) to provide a source of predisaster hazard mitigation funding that will assist States and local governments (including Indian tribes) in implementing effective hazard

______________

4The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (P.L. 100-707), signed into law on November 23, 1988; amended the Disaster Relief Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-288). The Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-390) amended the Stafford Act and authorized a program for predisaster mitigation. The Stafford Act and its amendments constitute the statutory authority for most federal disaster response activities, especially as they pertain to FEMA and FEMA programs, https://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?fromSearch=fromsearch&id=3564.

5Homeland Security Act of 2002, P.L. 107-296, November 2002, http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/law_regulation_rule_0011.shtm.

6https://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?fromSearch=fromsearch&id=3564.

mitigation measures that are designed to ensure the continued functionality of critical services and facilities after a natural disaster.7

Thus, Congress recognized the need to prevent or minimize disasters, if possible, through hazard mitigation measures and provided funding mechanisms for that purpose, and that such measures need to be coordinated with, or performed by, state and local governments (FEMA, 2010).

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 was passed in the wake of the events of September 11, 2001, and created DHS, merging the structure and missions of 22 separate federal agencies. The Act sets forth the primary missions of the department, which are to

(A) prevent terrorist attacks within the United States;

(B) reduce the vulnerability of the United States to terrorism; and (E)

(C) minimize the damage, and assist in the recovery, from terrorist attacks that do occur within the United States.8

Although the new department’s mission focuses on terrorism, DHS maintains responsibility for mitigating the effects of all kinds of disasters, including those from natural processes. Title V of the Act outlines those responsibilities

“…..to reduce the loss of life and property and protect the Nation from all hazards by leading and supporting the Nation in a comprehensive, risk-based emergency management program—

(A) of mitigation, by taking sustained actions to reduce or eliminate long-term risk to people and property from hazards and their effects;

(B) of planning for building the emergency management profession to prepare effectively for, mitigate against, respond to, and recover from any hazard;

(C) of response, by conducting emergency operations to save lives and property through positioning emergency equipment and supplies, through evacuating potential victims, through providing food, water, shelter, and medical care to those in need, and through restoring critical public services;

(D) of recovery, by rebuilding communities so individuals, businesses, and governments can function on their own, return to normal life, and protect against future hazards; and

______________

7http://www.disastersrus.org/fema/stafact.htm.

8http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/law_regulation_rule_0011.shtm.

(E) of increased efficiencies, by coordinating efforts relating to mitigation, planning, response, and recovery.”9

Although FEMA was placed within D, many of the traditional FEMA goals and activities continued to focus on natural hazards and an all-hazards approach to preparedness and response. The FEMA website states, “FEMA’s mission is to support our citizens and first responders to ensure that as a nation we work together to build, sustain, and improve our capability to prepare for, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate all hazards.”10 Thus, significant federal responsibility for some of the components of resilience building continues to lie within the mission of FEMA. However, the language of PPD-8 and the recommendations of the CRTF (see above) suggest that resources of DHS beyond FEMA are now expected to be brought to bear on the enhancement of national resilience.

Numerous policies to address specific components of community resilience have been introduced in Congress but have not been implemented; these bills nevertheless demonstrate cognizance of the need to strengthen specific aspects of resilience policy. For example, H.R. 2738, the Water Infrastructure Resiliency and Sustainability Act of 2011, has been introduced in the current Congress to address the supply and quality of water under conditions of climate change, a critical factor in the long-term resilience of communities.11 Similarly, legislation has been introduced in the past that recognized the broader sweep of considerations that affect national resilience. For example, in 2003, H.R. 2370, the National Resilience Development Act, which did not become law, was intended to create an interagency task force on national resilience focused on “increasing the psychological resilience and mitigating distress reactions and maladaptive behaviors of the American public in preparation for and in response to a conventional, biological, chemical, or radiological attack on the United States.”12 Such efforts, though recognizing some of the most complex issues of resilience and worthy of consideration, do not address, in a comprehensive way, the myriad resilience issues simultaneously at work in communities.

Other laws contribute to resilience by addressing specific aspects of national hazards. For example, the National Earthquake Hazard Reduction Program (NEHRP)13 provides for coordination among four federal agencies— FEMA, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the National

______________

9http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/law_regulation_rule_0011.shtm.

11Library of Congress, http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/thomas.

12National Institutes of Health, http://olpa.od.nih.gov/legislation/108/pendinglegislation/natresact.asp.

13NEHRP was created under the Earthquake Hazards Reduction Act of 1977, P.L. 95-124 (42 U.S.C. § 7701 et seq.), as amended by P.L. 101-614, P.L. 105-47, P.L. 106-503, and P.P. 108-360, http://www.nehrp.gov/about/PL108-360.htm.

Science Foundation, and USGS—to advance knowledge of earthquake causes and effects and to develop and promulgate measures to reduce their impacts at the community level, and the National Dam Safety Program, led by FEMA in coordination with other federal agencies, conducts research in dam safety, provides grants to 49 states to carry out state programs, and encourages individual and community responsibility for dam safety and related floodplain management.14 These programs are examples of federal programs that are designed to understand the scientific underpinnings of natural hazards, to assess regional and local exposure to those hazards, and to communicate with the local communities to help them enhance their resilience to natural hazards. Arguably, increasing resilience at both the community and national levels is a central function of many of these federal programs.

STATE AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES AND POLICIES

A discussion of improved national resilience may lead to a discussion of federal policies, but many of the critical policies and actions required for improved national resilience must be enacted and implemented at the state and local levels. Federal policies and programs provide broad national direction across jurisdictions, but many aspects of community and state resilience lie completely outside the authority and purview of federal policy. As discussed in the previous chapter, the federal government has little or no jurisdiction over the local planning process, over zoning laws or building codes, or over numerous other critical aspects of local community resilience. The state and local authorities, the private sector, and individual citizens have key responsibilities and opportunities to improve resilience. This division of responsibility is not simply an oversight or an accident of governance. On the contrary, different responsibilities were assigned to the federal and state governments early in the nation’s history, and the performance of specific functions by specific levels of governance arises from those principles.

At the local level, a number of jurisdictions and authorities may become involved in resilience planning, implementation, post-disaster recovery, and building, sometimes producing confusion or conflict about “who is in charge.” During major events, the abilities and resources at the local level may be exhausted and aid is sought from state or federal government agencies and national organizations.

States derive their authority to govern the areas within their boundaries from the Tenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”15 States support the

______________

14www.fema.gov/plan/prrevent/damfailure/ndsp.shtm.

15U.S. Constitution, http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/bill_of_rights_transcript.html.

communities within their borders in a variety of ways, and most states, in turn, give local counties, cities, and municipalities limited authority through the so-called Dillon Rule (Virginia Natural Resources Leadership Institute, 2011), or broader authorities (“home rule”) through their constitution or legislation.16 Explicit coordination of disaster resilience planning and actions at the state level is not common across the United States, although a few states have begun to adopt specific approaches and establish offices to address the issue (Box 6.5). Home rule gives local communities broad authority to enact their own laws within the bounds of state and federal constitutions. The extent of local authority and how it is exercised is the subject of much debate and legal process, but most cities and towns have at least some authority to formulate community development plans and land-use plans, to institute zoning laws, to adopt and enforce building codes, and to pursue other measures to suit the resilience needs of their own community. Community leaders and elected officials, with the help and support of the public, local businesses and utilities, nongovernmental organizations, and perhaps with state and federal government assistance, will largely determine whether their community resilience increases, stays the same, or decreases.

BOX 6.5

Coordination of Resilience at the State Level

Following the Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley’s service as chair of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Advisory Council’s Community Resilience Task Force and experiences gained during Hurricane Irene, which cut a swath across the state, he established the Office of Resilience within the Maryland Emergency Management Agency (MEMA). The office was assigned the mission of bringing together the focused efforts of the state, the business sector, communities, nongovernmental agencies and other partners including faith-based groups and other volunteer organizations to deal with resilience development across the state.

The new office is developing a network for effective engagement in all areas of emergency management among the private- and public-sector entities, vulnerable populations, and relevant regional groups. They are carrying this out through aggressive outreach, education, planning and training efforts, and information sharing and needs identification. Much was learned from predisaster planned beneficial partnerships that were exercised following Hurricane Irene that were able to bring together the support of big box stores, supply chain facilitation in the food sector, and state efforts to limit impediments to interstate commerce by avoiding such things as hours-of-service limitations and road closures. The Executive Director of MEMA sees the new office as essential to

______________

fill a distinct need in dealing with disasters and one that will greatly improve resilience at all levels.

Sources: Richard Muth, Executive Director, MEMA, personal communication, March 26, 2012; Angela Bernstein, Director Office of Resilience, personal communication, April 3, 2012.

The role of the federal and state agencies is to assist local communities in these efforts. For example, FEMA uses tools such as its Long-Term Community Recovery Planning Process: A Self-Help Guide (FEMA, 2005) to help local communities plan their long-term recovery after a disaster, and NOAA assists coastal communities in becoming more aware of and more resilient to tsunamis.17 Another approach, the Silver Jackets Program, was initiated by several federal agencies to reduce risk and increase resilience in a collaborative way with state and local agencies (Box 6.6). Many other federal programs provide similar guidance and assistance to local communities (see Table 6.1).

BOX 6.6

The Silver Jackets Program: Many Agencies—One Solution

The Silver Jacketsa program is an innovative state-agency-centered effort initiated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to bring together multiple state, federal, and local agencies (and where appropriate, tribes) to “learn from one another and apply their knowledge to reduce risk.” It links the federal family of agencies with state and local counterparts as well as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to deal with challenging pre- and post-disaster issues. Programs are initiated at the state level and currently 29 states have such programs under way.

Its goals are to:

• Develop ways to “collaboratively address risk management issues, prioritize those issues, and implement solutions”;

• Increase and improve risk communication through coordinated interagency efforts;

• Leverage available information and resources of all agencies such as FEMA’s RiskMAP program and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ (USACE) levee inventory and assessment initiative;

• Better coordinate hazard mitigation assistance by implementing in a collaborative manner those high-priority actions identified by state mitigation plans; and

• Identify gaps and conflicts among federal and state agency programs and provide recommendations for addressing these issues at both levels.

______________

17National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program, http://nthmp.tsunami.gov/.

To deal with a need for flood mitigation, the Indiana Silver Jackets team has been supported by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) stream gauging program, a USACE planning assistance team, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant Program in assisting communities damaged by the 2008 Midwestern flood. Through this collaborative state—federal effort, the state will be able to improve flood warning systems and acquire LIDAR mapping for all 92 counties.

In Iowa, the Silver Jackets Team brings together the efforts of USACE’s Rock Island and Omaha Districts, the National Weather Service, FEMA, USGS, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the Iowa Departments of Natural Resources, Emergency Management and Homeland Security, Agriculture and Land Stewardship, the Iowa Economic Development Authority, the Iowa Flood Center, the Iowa Utilities Board, and the Iowa Floodplain and Stormwater Management Association, an NGO. The team is currently dealing with issues in the Iowa-Cedar River watershed, including efforts to deal with the flood challenges of Cedar Rapids. When Cedar Rapids issues are under discussion, representatives from local agencies are included in the gatherings.

aWhy Silver Jackets? Following a disaster, federal agencies frequently appear at the site wearing different colored jackets. The name Silver Jackets was proposed as way to reflect the collaborative efforts of all the agencies involved in pre- and post-disaster activities. Source: www.nfrmp.us/state/about.cfm; Jerry Skalak, USACE -MVR, personal communication, March 29, 2012.

These principles and responsibilities that guide recovery also apply to developing community resilience more generally. For example, the recently released National Disaster Recovery Framework describes the roles and responsibilities for recovery, and the interactions of the different levels of government this way:

Successful recovery requires informed and coordinated leadership throughout all levels of government, sectors of society and phases of the recovery process. It recognizes that local, State and Tribal governments have primary responsibility for the recovery of their communities and play the lead role in planning for and managing all aspects of community recovery. This is a basic, underlying principle that should not be overlooked by State, Federal and other disaster recovery managers. States act in support of their communities, evaluate their capabilities and provide a means of support for overwhelmed local governments. The Federal Government is a partner and facilitator in recovery, prepared to enlarge its role when the disaster impacts relate to areas where Federal jurisdiction is primary or affects national security. The Federal

Government, while acknowledging the primary role of local, State and Tribal governments, is prepared to vigorously support local, State and Tribal governments in a large-scale disaster or catastrophic incident.18

However, many communities do not address, in a comprehensive manner, the numerous and complex issues that produce resilience until after a severe event occurs. The best time to develop resilience in a community is while the community is being planned and built or reconstructed after a disaster, and that is when the state and federal agencies may have somewhat limited roles. Therefore, it is critical that individuals and community leaders understand their roles and responsibilities relative to state and federal responsibilities, and that they consciously seek to improve the resilience of their community through their decisions and governing processes.

An example of building community resilience with specific local policies is through the implementation of resource planning policies by states and regional authorities that recognize threats from natural hazards also contribute to community resilience. For example, the State of Massachusetts recently adopted a climate change plan (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2011) to help avoid the consequences of anticipated changes resulting from climate change, and the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (2011) issued a set of recommendations targeted at helping the San Francisco Bay area prepare for changes resulting from climate change and sea-level rise. Maryland has recognized the vulnerability of its coastal zones, particularly in light of the potential changes in sea level and climate, and has developed adaptation strategies for their coastal areas (Maryland Commission on Climate Change, 2008). Efforts such as these contribute to community and national resilience by identifying hazards and threats before a disaster occurs, allowing local administrations to adjust their development plans to protect their citizens.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES: POLICIES AND PRACTICES THAT NEGATIVELY IMPACT RESILIENCE

Much of this chapter has focused on policies and programs that provide the framework for governance, responsibilities, and support of community resilience from the top down. But community resilience may also be affected by policies that are seemingly unrelated to resilience. Policies and practices

______________

18http://www.fema.gov/national-disaster-recovery-framework, p. 9.

promulgated to address a wide variety of other national problems may have the unintended consequence of reducing resilience. Furthermore, in some cases, failure to enact a policy that would increase resilience results in a deterioration of resilience. In other words, the absence of a specific beneficial policy is, in itself, a policy. We present here a few examples of policies where unintended consequences have effectively reduced community resilience.

Agricultural policies provide one example of unintended consequences that reduce resilience. In this example, shifts in agricultural practice in the United States in response to farm policies designed to improve field drainage and productivity have unintentionally but significantly exacerbated flooding in the Midwest. Westward expansion of farming during the 19th century motivated farmers to improve the drainage in flat or low-lying farm fields to make them more productive. Improvement in field drainage was accomplished by the installation of drain tiles or perforated pipes just under the surface of the field to remove excess water. The effect of this accelerated drainage during the spring months of each year was to move water quickly from the fields to the streams and rivers, which exacerbated——and still exacerbates—flooding along many stream and rivers in the Midwest.

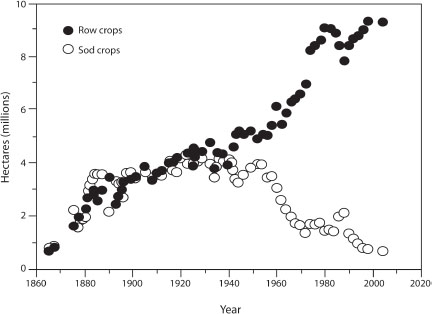

The contribution of field drainage to flooding was made even worse after the implementation of new agricultural policies following the Great Depression. As part of his suite of New Deal policies, President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed that true prosperity would not return to the nation until farming was prosperous. Roosevelt’s Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 made federal price support mandatory for corn, cotton, and wheat and established permissible supports for many other crops and farm products.19 The result of this policy was a fundamental shift in farming practice to row crops (mainly corn and soybeans) replacing traditional sod farming (perennial vegetation such as hay and densely sown small grains including oats, wheat, barley, triticale, and rye undersown with pasture grasses and legumes) as demonstrated for Iowa in Figure 6.1 (Jackson, 2002; see also Mutel, 2010).

______________

19Agricultural Adjustment Act, P.L. 75-430, United States Code, Title 7, Chapter 35, http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/usc.cgi?ACTION=BROWSE&TITLE=7USCC35&PDFS=YES.

FIGURE 6.1 Shift in farming practice in Iowa to row crops from earlier focus on sod crops around 1938 as a result of the Agricultural Adjustment Act. Source: Adapted from Jackson (2002).

For more than 60 years (1870 to the 1930s) Iowa farmers had maintained about 50 percent sod crop, but with passage of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 row crops began to dominate, with dramatic implications for flood resilience (Jackson, 2002). The traditional sod crops had dense root masses that absorbed rainfall without runoff and released it back to the atmosphere via transpiration and through underground flow into both shallow and deep aquifers (Jackson and Keeney, 2010). Because the crops were perennial, after harvest the root mass remained and was not tilled up, thus retaining and improving top soil. Knox (2006) describes the agricultural conversion of prairie and forest in the upper Mississippi Basin as the most important environmental change that influenced fluvial (river and stream) activity in this region in the past 10,000 years.

Even without impacts of climate change, farm practice (responding in part to policy) has significantly increased the flood potential in the Midwest. The overall effect of facilitating the drainage of millions of acres of farm fields through underground drains, combined with the shift from sod crops to row crops and the encroachment of many communities into the floodplain, was to reduce the resilience of cities and towns along Midwestern rivers by increasing the likelihood and intensity of flooding. To address this problem, Jackson and Keeney (2010) summarize a variety of proposed novel mitigation strategies including crop rotation, strip-cropping practice, crop mixing, as well as setting

aside small percentages of row-crop land for perennial “buffer strips” along streams. This example, like many others, contains many variables and many forces, and cannot be distilled into a simple choice between flooding and soggy fields or subsidies that encourage unsustainable farming practices, but it serves to demonstrate that unintended consequences of well-intentioned national agricultural policies may ultimately reduce local resilience.

Forest management policy provides a second example of unintended consequences of policies or practices. A century of aggressive suppression of wildland fires combined with recent broad and extended periods of drought, have substantially altered many of the nation’s forests and have resulted in devastating wildfires at the wildland—urban interface in many locations across the United States. These fires are difficult to control, threaten adjacent urban areas, and are expensive to fight (Cohen, 2008). Corrective policies that emphasize fuel management are often underfunded or infeasible. In their review, USDA ecologists Donovan and Brown (2007) recommend a different approach to wildfire management that focuses on encouraging managers to balance short-term wildfire damages against the long-term consequences of fire exclusion. The approach deemphasizes fire suppression. Recent changes in the management of wildland fires recognize the effects of past policies on forested communities and these new policies increase the resilience of those communities and accommodate the sustainability of ecosystems (National Wildfire Coordinating Group, 2009).

Likewise, government policies for coastal zone management have traditionally been intended to balance economic development along the coasts with preservation of coastal habitat and environment while recognizing the risks of development along the coast.20 Now more than 50 percent of the U.S. population lives within 50 miles of a coastline and this proportion is expected to increase in the future.21 Economic development, including residential, commercial, recreational, and industrial development in the coastal zone has greatly increased the exposure to storm surge, coastal erosion, and sea-level rise. Federal policy for coastal zones has been to encourage and support coastal states in the proper development and management of their coastal areas, but some states have placed short-term economic development above long-term safety and community resilience.

Perhaps the classic example of unintended consequences of well-intentioned historical policies is the effects of Mississippi River flood management on the City of New Orleans and the Mississippi River delta communities. This series of historical decisions and engineering efforts has been thoroughly documented in several publications (Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana, 2012). Many decades of efforts to levee and channel the Mississippi River to reduce flooding and facilitate navigation along

______________

20Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended through P.L. 109-58 and the Energy Policy Act of 2005, http://coastalmanagement.noaa.gov/czm/czm_act.html.

the course of the river as well as the construction of large dams on the main stem of the Missouri River combined with construction of channels for transportation of oil and gas exploration have starved the Mississippi River delta of sediment and have resulted in increased vulnerability to tropical storms and hurricanes in the Mississippi delta region. The normal natural processes of sedimentation and delta growth were halted and the subsidence of the delta edifice was not counteracted by the deposition of new sediments across the delta. The result is a subsiding and shrinking delta with reduced capacity to mitigate storm surge. These effects have severely degraded the resilience of the delta and the human settlements in the region, including New Orleans. These historic policies have made the entire Mississippi delta region less resilient.

In addition to unintended consequences of individual policies, the lack of communication and coordination among federal agencies may have real consequences for communities or victims of a disaster. Sometimes an individual policy may be beneficial, but when multiple federal agencies independently apply mutually unknown policies to the same geographic area or structure, those policies may be contradictory and may inhibit recovery or slow the enhancement of resilience. For example, if one agency bases the distribution of funds on the value of a property on a floodplain at the same time that a policy of a different agency is changing the value of that property through acquisition or demolition, the property owner may be caught in a quandary and may be excluded from a funding mechanism through no action or fault of his or her own. The application of federal policies either before or after disasters needs to be informed by the goals of the community and by the knowledge of other policies that are being applied by other agencies. This coordinated application of policies will only be achieved if communication and coordination among federal agencies is achieved, and if agencies are aware of the needs and priorities of the affected community or individual.

An unintended consequence of certain security policies adopted after the September 11, 2001 World Trade Center attack is the difficulty of some local governments and the private sector in gaining access to certain information necessary to secure privately owned infrastructure against various hazards and to develop plans to deal with emergency events. A report on National Dam Safety to FEMA by the University of Maryland identified the restrictions placed on release of information on dam integrity and potential downstream inundation as significant impediments to disaster planning and preparedness (Water Policy Collaborative, 2011). A 2012 Report by the National Research Council on dam and levee safety and community resilience similarly concluded that

Those subject to the direct or indirect impacts of dam or levee failure are also those with the opportunity to reduce the consequences of failure through physical and social changes in the community, community growth planning, safe housing construction, financial planning (including bonds and

insurance), and development of the capacity to adapt to change. (NRC, 2012, p. 107)

As pointed out by Flynn and Burke (2011), investment and operational decisions by corporations that own critical infrastructure may be made without full security awareness because information that has been classified by the Department of Homeland Security is sometimes not available to the corporate executives making the decisions. Because an increase in community resilience requires coordination and cooperation among all key players within the community, including the private-sector owners of infrastructure, it is vitally important that communities be aware of prescribed rules and methods of sharing restricted information in a secure way among all partners, including the vital private-sector partners, as detailed in Executive Orders 12829,22 12958,23 and 13292.24 Some types of data may be sensitive, but giving local partners the opportunity to work with state and federal stakeholders on equal footing is important to build long-term resilience.

Finally, even some policies that seem unrelated to community or national resilience may unintentionally and negatively affect resilience. A recent example of this is the Budget Control Act of 2011. The President signed the Budget Control Act of 2011 into law (P.L. 112-25) on August 2, 2011. The purpose of that legislation is primarily to increase the U.S. debt limit, establish caps on the annual appropriations process over the next 10 years, and to create a Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction that is instructed to develop a bill to reduce the federal deficit over the 10-year period. One provision of this new law that affects U.S. national resilience is an amendment to Section 251 of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985. That amendment provides for disaster relief appropriations each fiscal year based on “the average funding provided for disaster relief over the previous 10 years, excluding the highest and lowest years.” In this bill, “the term ‘disaster relief’ means activities carried out pursuant to a determination under section 102(2) of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 5122(2)).” As discussed elsewhere in this report, developing national resilience encompasses more elements than disaster recovery alone. Building a resilient community requires thoughtful and strategic long-term investments in multiple aspects of the physical and social fabric of communities that contribute to resilience. Of course, disaster recovery is an integral part of that process because the ability of communities to recover after a disaster, and the way that they recover, is closely tied to becoming more resilient to subsequent trauma. Therefore, the federal commitment to assist communities in a timely fashion is central to the long-term resilience of communities. When a community’s

______________