3

Overview and Statement of the Problem

BACKGROUND OVERVIEW: EXPLORING THE INVISIBLE BARRIER TO ACHIEVING ORAL HEALTH

Dushanka Kleinman, D.D.S., M.Sc.D. University of Maryland School of Public Health

Kleinman noted that health literacy provides the foundation for oral health literacy, as it does for any other area of health. Furthermore, the definition of health literacy developed by Ratzan and Parker (2000) is applicable in the context of oral health literacy with minor adaptation. Kleinman defined oral health literacy as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic oral and craniofacial health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.

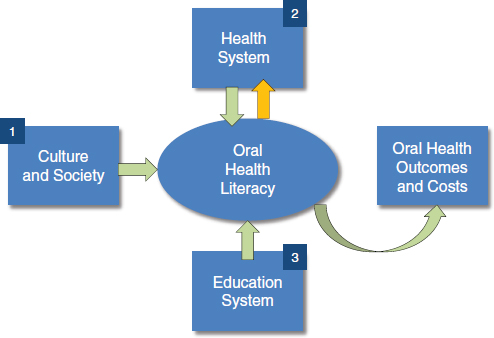

The IOM framework for health literacy found in the report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion (IOM, 2004) can also be adapted for use in the context of oral health literacy (Figure 3-1). According to this framework, oral health literacy exists within the context of culture and society, the education system, and the interaction that individuals have with the health system, knowing that oral health literacy then leads to, and complements health, oral health, and health outcomes and costs.

Several national and state efforts have highlighted the need for oral health literacy and strategies to achieve it. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General (2000) concluded that oral health is essential to general health and well-being, but that not all Americans are achieving

FIGURE 3-1 Oral health literacy framework.

SOURCE: Adapted from IOM, 2004.

the same degree of oral health. The report described the silent epidemic of oral diseases that affect the nation’s most vulnerable members. The report also concluded that although common dental diseases are preventable, not all members of society are informed about or are able to avail themselves of appropriate oral health promoting measures. Similarly, not all health providers may be aware of the services needed to improve oral health. Improvements in oral health will require educating the public, providers, and policy makers about the science-based interventions that prevent oral diseases.

In 2003, specific actions to promote oral health were identified in A National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health (HHS, 2003). This report, which resulted from a public–private partnership between the Office of the Surgeon General and various organizations, identified five major actions that are needed:

- Change perceptions of oral health.

- Overcome barriers by replicating effective programs and proven efforts.

- Build the science base and accelerate science transfer.

- Increase workforce diversity, capacity, and flexibility.

- Increase collaborations.

For each of these actions, the need for oral health literacy was highlighted. For example, in the area of workforce capacity, training in communication and counseling was viewed as critical. The National Call to Action report concluded that there is a perception that oral health is less important than, and separate from, general health. The report discussed how activities to overcome this perception can start at grassroots levels and then lead to a coordinated national movement to increase oral health literacy.

A workgroup sponsored by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research was convened to set a research agenda for oral health literacy. This research agenda was published in the Journal of Public Health Dentistry.1 The research agenda was structured around three questions:

- What types of literacy tasks do people need to perform within the context of oral health (descriptive studies)?

- Is literacy a good predictor of oral health outcomes above and beyond the level of education (correlational studies)?

- How can we improve the practice of communicating oral health information (intervention studies)?

This workgroup focused on functional oral health literacy and examined variables that allow individuals to make decisions about personal health, health system navigation, and community program participation. The group enumerated the many skills necessary for effective decision making (i.e., reading, writing, speaking, listening, numeracy, interpreting visuals) and identified participants that need to be engaged (e.g., health care providers, the public, policy makers, and health system leaders). Communication was emphasized throughout the report as a means of furthering functional oral health literacy. The report from this group posed several questions to guide research and recommended that a taskforce be formed to define a detailed agenda.

The first set of questions concerned measurement. How can oral health literacy be measured? How would methods proposed by the group relate to measures of health literacy?

The role of providers was another area for which questions were developed. What are providers doing to improve health literacy? What roles can they play to increase health literacy? What are the best procedures for them to use when assuming these roles?

In preparing the workforce, the report included the following questions: What are dental health professions education institutions doing to

_____________________

1The title of the 2005 article is “The Invisible Barrier: Literacy and Its Relationship with Oral Health” (Journal of Public Health Dentistry 65(3):174-182).

prepare the workforce to contribute? What methods are being used to teach communication skills to our providers? What are the best teaching methods?

Finally, in terms of the ultimate outcome, the report authors asked, “What role does health literacy play in oral health outcomes?”

Progress has been made since the workgroup convened in 2005, Kleinman said. For example, some measurement issues have been addressed and aspects of how oral health literacy affects health outcomes have been explored. Support from government agencies and foundations have contributed to the oral health literacy research agenda. Examples of funded projects include the following:

- Examination of oral health literacy in public health practice

- Health literacy and oral health knowledge

- Latinos’ health literacy, social support, and Oral Health Knowledge, Opinions and Practices (OH-KOP)

- Development of an instrument to measure oral health literacy

- Culture and health literacy in a dental clinic

- Health literacy and oral health status of African refugees

- State oral health literacy models and programs

The dental profession, state oral health programs, and the dental industry have also been taking action, said Kleinman. For example, the American Dental Association’s Health Literacy in Dentistry Action Plan 2010-2015 (ADA, 2009) includes a strategic plan to improve oral health literacy. Two IOM reports gave visibility to oral health literacy (IOM, 2011a,b). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) commissioned these IOM reports. Part of the charge to the IOM committee that produced Advancing Oral Health in America (IOM, 2011a) was to explore ways of improving health literacy for oral health. That IOM report concluded that oral health literacy of individuals, communities, and all types of health care providers remains low. Kleinman stated that this conclusion was based on results of statewide and national surveys that show the public lacks understanding about how to prevent and manage oral diseases; the impact of poor oral health; how to navigate the oral health system; and the best techniques in patient-provider communication.

The report recommended that all relevant agencies of the Department of Health and Human Services undertake oral health literacy and education efforts aimed at individuals, communities, and health care professionals. These efforts could include

- community-wide public education on causes of oral diseases and effectiveness of preventive interventions,

- community-wide guidance on how to access oral health care, and

- professional education on best practices in patient-provider communication skills.

The second IOM report, Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations (IOM, 2011b), concluded that poor oral health literacy contributes to poor oral health and lack of access to care.

Based on her review of major national reports on oral health literacy, Kleinman concluded that

- research workshops and national reports have identified areas that warrant attention,

- funding agencies and foundations are providing initial support, and

- to address recommendations and streamline efforts a comprehensive plan to address oral health literacy through research, education, services, and policy is needed.

Amid Ismail, B.D.S., M.P.H., M.B.A., Dr.P.H. Temple University

Dr. Ismail has spent nearly 20 years focused on understanding the determinants of dental caries in subgroups of the U.S. population. Over the previous 3.5 years he has been a dean of the Maurice H. Kornberg School of Dentistry, which is located in North Philadelphia, an area with a heavy concentration of low-income, minority-group individuals. The dental school provides care to about 22,000 residents of the community annually and plans are for the clinical service to expand to serve 50,000 individuals. The care delivery paradigm is changing to include a focus on oral health literacy.

Ismail said that innovation requires thinking about what is needed in the future. Henry Ford was quoted as saying, “If I had asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me a faster horse.” Innovation is key for moving forward to reduce inequalities and disparities in health in the United States. He added that innovation involves thinking outside of the current box and considering new multifaceted approaches. The American Dental Association (ADA) defines oral health literacy as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appro-

priate oral health decisions. Obtaining and processing information may be difficult for people who do not have levels of literacy that would allow them to manage and navigate a health care system. A major task, then, is translating the definition of oral health literacy into actions that enable individuals to obtain and process oral health information.

One major barrier to promoting oral health is the lack of oral health literacy on the part of health care providers. Policy makers must also become oral health literate, said Ismail. So too must communities because they also need to obtain, process, and understand information in order to take actions that promote good oral health. Oral health literacy has to become part of the community culture.

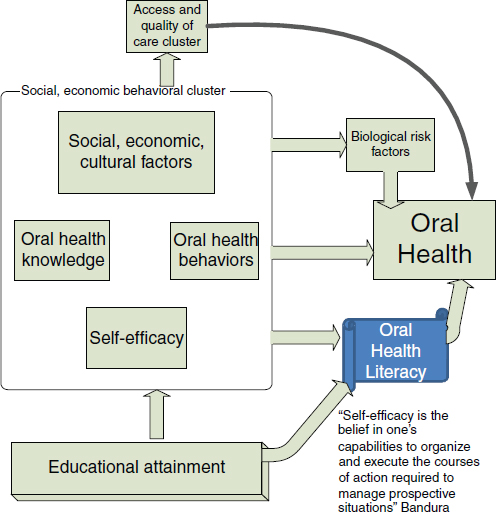

Ismail presented a model framework for understanding oral health literacy that includes social, behavioral, and economic determinants (Figure 3-2). Oral and dental diseases have very strong social, behavioral, and economic determinants and yet systems are not designed to address these factors. The Kornberg School of Dentistry at Temple University has a philosophical rule that states, “If a patient comes to the clinic with pain, they do not leave the clinic with pain.” The care model in urban and rural communities in the United States where access to care is problematic requires systems that are tailored to the needs and demands of the population. People should not have to conform to a traditional way of providing care that does not address their needs. This care model should guide how the social and economic differences that contribute to poor oral/dental health are addressed, Ismail said.

In the model displayed in Figure 3-2, oral health knowledge, oral health behaviors, and self-efficacy are important components of the oral health literacy framework. Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations (Bandura, 1994). Also central to the model is education, a key determinant of oral and dental disease prevalence and severity.

Many factors are involved in the access and quality of care cluster of the model. For example, in the area of caries diagnosis and management, the more technology that is introduced into the system, the more the focus is on filling cavities instead of preventing the progression of non-cavitated carious lesions. In part, this reflects the current system of economic incentives related to coding and reimbursement for dental providers.

Although biological risk factors have a significant role to play, Ismail stated that in his opinion 70 percent of the problems in oral health literacy can be traced to the factors in the boxed area of Figure 3-2 (e.g., social, economic, cultural factors, self-efficacy). Relatively few investments have been made in these areas to address these determinants of disparities of oral and dental health.

Data on the burden of oral and dental disease from the National

FIGURE 3-2 Framework for understanding oral health literacy.

SOURCE: Ismail, 2012.

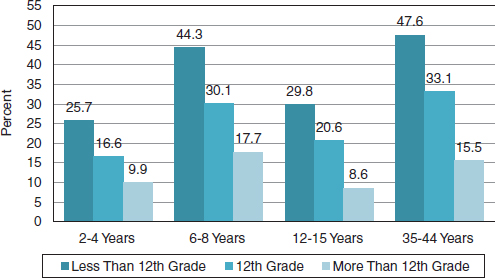

Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) survey show a significant gradient by education for untreated caries (Figure 3-3). There are large differences between those with and without a high school education.

The relationship between untreated caries and education is troubling. A troubling statistic is that in many areas of the country the majority of high school students do not graduate from high school, which leads one to expect an increased burden of chronic diseases in this population.

Studies have shown that, in general, individuals who are health literate have better health outcomes than individuals with low health literacy. However, well-designed research studies on oral and dental health and health literacy are lacking and are needed (Berkman et al., 2011).

FIGURE 3-3 Untreated caries prevalence by education and age group.

SOURCE: Ismail, 2012.

National survey data provide evidence of a relationship among oral and dental health, general health, and quality of life (Seirawan et al., 2011). These data show that 20 percent of the population reported having dental pain in the last year (Table 3-1). Ten percent of the population reported that life, in general, was less satisfying because of dental problems.

Ismail said that there is evidence that populations experience persis-

TABLE 3-1 The U.S. Population Responses to Selected OHIP-7 Questions, NHANES III (n = 6,183)

| Oral Health Impact | Often/Occasionally |

| How often during last year have you had painful aching anywhere in your mouth? (Physical Pain) | 19.9% |

| How often during last year have you felt life in general was less satisfying because of problems with your teeth, mouth, or dentures? (Handicap) | 10.1% |

| How often during last year have you avoided particular food because of problems with your teeth, mouth, or dentures? (Physical Disability) | 15.3% |

| How often during last year have you been self-conscious or embarrassed because of your teeth, mouth, or dentures? (Psychological Disability, Psychological Discomfort) | 12.6% |

SOURCE: Seirawan, 2011.

tently high levels of oral and dental disease because key determinants of health have not been addressed. He added that the current model of care and reimbursement will not succeed in controlling dental diseases. For example, 60 percent of Alaska Native children have extensive dental disease (Riedy, 2010) and according to Ismail, the real determinants of this epidemic are not being addressed.

Poor oral and dental care takes a considerable economic toll. In Philadelphia, $11 million was spent to treat dental caries in young children under general anesthesia or IV sedation, Ismail said. One in five of these children will return for in-hospital dental care within the year. The impact of treatment for early childhood caries under general anesthesia is significant. According to one British study, 90 percent of parents reported that their child experienced pain, and a significant proportion had difficulties with chewing or talking (Olley et al., 2011). In addition, children were reported to have emotional and social functioning problems related to their dental disease. According to this study, the socioeconomic status of the parent was predictive of the burden associated with dental caries. When the parents of children who had received dental care in the hospital were asked what kinds of supports would be helpful in future, they reported wanting tooth brushing education programs in schools, oral health education, community-based interventions, and home visits. Ismail said there is a tendency to pay for procedures, not outcomes, and there is a misplaced focus on dental care by professional providers, rather than on community-based approaches to promoting health.

Data from a study conducted in Nova Scotia, Canada, showed that the prevalence of dental caries and the progression of the disease in children varied by parental educational attainment, even though there was universal access to a publicly financed dental care program (Ismail et al., 2001). The study’s authors concluded that disparities in oral health status cannot be reduced solely by providing universal access to dental care and that focused efforts by professional and governmental organizations should be directed toward understanding the socioeconomic, behavioral, and community determinants of oral health disparities. In a 2010 study undertaken in New Zealand, the prevalence of untreated caries in school-age children was highest among those children living in the most deprived neighborhoods. The disparities exist despite a system of public health that reaches children in the school and provides them with preventive services. These studies illustrate the need to address oral and dental health from a wider community or public health perspective, not just from the perspective of what dentists or health providers can accomplish, Ismail said.

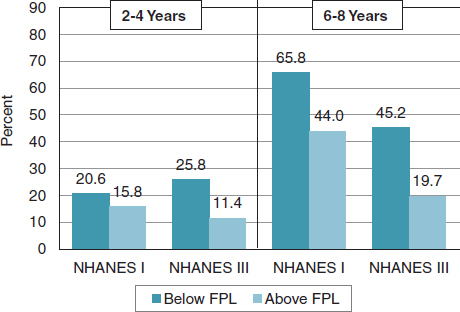

Significant disparities in dental disease exist in the United States. Data from the NHANES between 1971 to 1975 and 1988 to 1994 show an

FIGURE 3-4 Trends in untreated decay in the United States.

SOURCE: Ismail, 2012.

increase in entry to decay among children ages 2 to 4 living below the federal poverty level (Figure 3-4).

Education and poverty are important determinants of periodontal disease, oral cancer, and caries. For oral cancer, there are significant variations in rates of disease by race/ethnicity, Ismail said. Existing attempts to address these disparities tend to be piecemeal in nature and lack a necessary focus on systems of care. There is, Ismail said, a need to create a new national strategy that focuses on health promotion.

Ismail concluded by saying that literacy is an important foundation for health. In order to achieve literacy, interventions must range from the global to the community, to the family, and to the individuals within the family.

Roundtable member Patrick McGarry began the discussion of the session presentations by noting that family doctors sometimes have a difficult time convincing parents to vaccinate their children because of misinformation about vaccine safety. He asked the panel how to address opponents of public water fluoridation programs. Kleinman said that a focus on the science base, for example, research that supports water

fluoridation as safe and effective, is necessary to counter misinformation. Some of the controversy and uncertainty surrounding public water fluoridation programs stems from a lack of ongoing community education for individuals, families, and policy makers about this communitywide preventive measure. In addition to developing new disease preventive interventions, accurate information about existing effective prevention programs needs to be reinforced, Kleinman said.

Ismail added that communication technology has fueled the fluoridation controversy. There were debates about water fluoridation when it was initiated in the 1940s and 1950s and continuing throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In an Internet search on water fluoridation, Ismail found that about 80 percent of the coverage is negative. Ismail indicated that it is very difficult to judge which sites are credible. He added that even some professions, including dentists, are misled by information obtained on the internet. The health community and public health organizations need to use the same tools to disseminate the known benefits of effective health interventions such as water fluoridation. Water fluoridation works and no measureable adverse health effects have been identified at the levels of fluoridation that are used. Communication strategies need to be developed to successfully deliver this message.

Roundtable member Ruth Parker asked the panel, “If you could give three messages to everyone about oral health, what would they be? What are the three things that everybody should know?” Kleinman responded with three messages:

- The key intervention to prevent the most common oral disease, tooth decay, is water fluoridation.

- Fluoride used in the home, along with dental sealants, effectively counters tooth decay.

- Early screening and diagnosis for oral cancer and periodontal disease reduces morbidity and mortality.

She added this simple message, “Oral and dental health are important for your happiness, enjoyment, and pain-free life.”

Roundtable member Cindy Brach asked Ismail how consumers of oral and dental health services can judge whether or not their provider is actually recommending treatments that are appropriate and needed. Her question arose from his comment that dentists sometimes fill caries when a restorative approach could be taken. In addition, she asked how dental health consumers could become advocates for appropriate care for themselves and their families. Ismail said that the reason dentists opt for a more aggressive approach is because dental students and the providers who graduated from dental school have learned to drill in response to

caries. The payment system encourages this practice. He pointed out that caries occur in stages, and that there are stages that require filling and other stages that do not. Unfortunately, reimbursement systems do not provide payments for the more restorative approach.

Consumers can start to ask questions and seek providers who adhere to a philosophy of conservatism. He noted that it is better to be conservative and attempt to preserve healthy tooth structure, than to put a foreign material into a tooth when it is not needed. A dental student may complete an excellent restoration, but if the restoration is placed in a tooth that should not have been filled, this practice represents the lowest level of quality of care. Ismail mentioned that he is organizing a workshop to shift the paradigm from automatically filling a cavity to a focus on prevention. Some tooth decay can be arrested, re-enameled, or filled in a very conservative way. Plans are under way to develop a protocol that incorporates this more conservative approach accompanied by a video that illustrates this method. Ismail added that, in addition to educational interventions, different payment mechanisms are needed for the management of oral and dental disease that reflect and support evidence-based practice.

Roundtable member Susan Pisano asked the panel if key questions have been developed that consumers should ask when they interact with their dental providers. She observed that consumers may not be aware of treatment options for caries and that a set of key questions could help bring about a discussion of the treatment options Ismail is promoting. Ismail was not aware of the development of key questions, but thought that this would be very helpful. He observed that health insurance plans have a key role to play in terms of the change process in collaboration with the medical, dental, and pharmacy schools.

Roundtable member Paul Schyve observed that individuals have access to information through the Internet and elsewhere, but may lack the critical thinking skills necessary to understand the information. He asked the panel to address this issue which is central to achieving health literacy. Kleinman said that education at all levels, not just in the health professions, needs to be examined. Undergraduate public education has shifted its core curriculum to focus on critical thinking. Social networks and the Internet will be a major tool to foster critical thinking, but in addition, enhancements to health education are needed at all levels, from kindergarten through college and professional school. Decision models might be needed as aids to assist people. Ismail agreed that critical thinking needs to be ingrained into educational programs, including those for health providers. He added that there also needs to be a focus on research to answer questions that the public is asking, and

in addition, a mechanism to translate research into messages that the public will understand.

Mary Lee Conicella of Aetna addressed the high rate of general anesthesia use among children being treated for dental problems in Philadelphia. The data on 2- to 5-year-olds covered by Aetna’s dental plans, suggest that only 0.13 percent of this group is being treated with general anesthesia. She said that having a benefit that improves children’s oral health likely reduces this practice. She asked the panel how the use of such aggressive treatment of children relates to health literacy. In other words, “Does having a dental insurance benefit help children and parents with health literacy?” She also asked the panel, “How can we improve health literacy even for children who do not have a dental insurance benefit?”

Ismail responded that one explanation for the relatively low use of general anesthesia among children is that Aetna’s program for Medicaid started very recently. General anesthesia and IV sedation in severe early childhood caries is a treatment covered by Medicaid. Education is a key variable in this population. According to the NHANES data, children of highly educated parents receive three to four times more sealants than children with parents of lower educational attainment. When preventive services are not provided to children in low socioeconomic environments, disparities in dental health are perpetuated.

Roundtable member Laurie Francis thanked Ismail for including self-efficacy and social determinants in his discussion of oral health literacy. She pointed out the importance of having information that is patient-centered and asked Ismail how self-efficacy, patient priorities, experience, and confidence levels can be incorporated into the health literacy conversation. She observed that these concepts often seem to be left out of the conversation. Ismail described how the dental school at Temple University is redefining its outcomes statement. The Commission on Dental Accreditation requires dental schools to demonstrate that they provide patient-centered care, evidence-based care, and comprehensive care. The students will learn how to work according to these three concepts. When measuring quality of oral health care, outcomes need to be included in the measurement set to gauge improvements in knowledge, health, and quality of life. Self-efficacy could be incorporated into an outcomes measure along with patient behaviors and practices. Change is inevitable when accreditation depends on the demonstration of such outcomes. Schools may need guidance or a formula for how to incorporate these concepts into their curriculum.

Kleinman added that tools—for example, the patient health record—allow patients to bring signs and symptoms that are noticed at home into

the conversation with their provider. Accountable Care Organizations2 also allow providers to reach beyond those who seek care, to the community at large. Examining hospital readmission rates and emergency room use broadly, not just in the oral health area, can be very instructive, but these are indicators of a failing system.

Roundtable member Leonard Epstein recalled Congressman Cummings’ story of his family’s use of turpentine, cotton balls, and Orajel to manage dental problems. He asked the panel if collaborative activities between oral health and pharmacy had taken place, especially at the retail level in underserved and disadvantaged communities. In these neighborhoods, pharmacists are often the primary points of care. Ismail agreed that this is a very promising approach and that the discussion between the dental community and pharmacists has just started. Pharmacists could be particularly helpful in the age group that dental providers often miss, children up to age 5, because pharmacists often interact with parents regarding the care of young children. Pharmacists could provide a prescriptive health message about how to prevent early childhood caries.

Kleinman provided information on a past survey she conducted as part of a student class project on what retail pharmacies offer to treat oral and dental problems such as tooth pain, mouth sores, and herpes simplex. The survey found that oral and dental products in the pharmacy are extensive and with little or no guidance for the public seeking relief. Many people are dealing with mouth sores superficially and not seeking diagnostics and treatment early in the course of the disease. There are opportunities across the age spectrum to intervene with oral and dental health information. It is critical to reach children because of the opportunities for prevention, but adults are also a key audience in terms of the prevention of oral cancer. Kleinman noted that a partnership between pharmacists and dental providers, to her knowledge, has not yet been formalized, but that such a partnership is an important one to pursue.

Roundtable member Will Ross highlighted the problem of children’s early and frequent exposure to sugary food and drinks which contribute to the development of caries right after primary teeth come in. He asked the panel about opportunities for formal collaboration with dietary and nutrition services and providers, both locally and nationally. Kleinman noted that the American Dental Association has brought a number of professional groups together over the years to foster collaborative efforts

_____________________

2“Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers, who come together voluntarily to give coordinated high quality care” to their patients. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ACO/index.html?redirect=/ACO/ (accessed June 15, 2012).

related to diet and nutrition. It is likely, however, that these efforts need to be revisited and reenergized.

Ismail recounted a successful collaboration between medical students at Drexel University and the dental school at Temple University. A group of about 15 to 20 medical students from Drexel comes to the dental school to learn about oral surgery, dental and craniofacial diagnosis, dental radiology practices, and pediatric dentistry. Other dental schools have similar collaborative programs. Perhaps trained medical students could receive some sort of board certification as a medical student in dental training, he said. The dental professionals need to reach out to all health professions.

Roundtable member Cindy Brach asked the panel to describe what health literate consumers of oral health do, not what they know, but what they do. Ismail said that an oral health literate consumer should question all information that is provided to them. He added that in order for successful communication between patients and providers, providers need to be trained to accept questioning and to provide appropriate health education. Kleinman added that consumers need to be particularly diligent about asking questions about any tissue removal. She cited the importance of new evidence regarding disease processes in dentistry and the relatively new focus on conservation. It is now possible to intervene once the disease process has started and reverse it. The practice of re-mineralizing teeth is not familiar to parents and other adults who received much of their dental care as children 20 to 40 years ago. There is a new focus on promoting health, and not just preventing disease.

Roundtable chair George Isham highlighted the importance of asking questions of dental care providers. Some of the same questions that are relevant in the medical context are appropriate for dental providers, for example, how many procedures they have performed and the frequency of complications. It is also helpful to ask providers to explain why a procedure needs to be performed. A provider may be offended by such questions, but consumers are entitled to this kind of information. Developing a series of questions for consumers for general dentistry and specialty dental services could be quite helpful according to Isham. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has developed similar materials for medical encounters and procedures. Brach added that AHRQ has a program called “Questions Are the Answer.” Dental oriented materials could be developed through this program.

Isham concluded the discussion by reiterating the need to educate and train dental and health professionals to encourage questions from their patients, and to be open and receptive to questions.