For purposes of brevity and consistency, the committee has chosen to use the term “community-based prevention” to describe community-based prevention policies and wellness strategies. This chapter begins with a discussion of the terms “community,” “community-based,” and “community-placed.” It then identifies important features of community-based prevention, gives a brief history of the development of community-based prevention programs, and describes strategies and a sampling of models used. The chapter also examines the evidence used and the difficulties inherent in the evaluation of effectiveness as well in describing results from some program evaluations.

Community means different things to different people in different contexts. For example, Cheadle and colleagues (1997) refer to community as a location or place. Brennan (2002) writes that “community may be a more abstract concept, such as a neighborhood, defined by a sense of identity or shared history with boundaries that are more fluid and not necessarily identified exactly the same by all members.” For some, community may be defined by common beliefs or ideologies (e.g., religion or politics), by activity (e.g., swing dancing or running), by social responsibility, by race or ethnicity, by socioeconomic status, or by a sense of belonging (Israel et al., 1994; Patrick and Wickizer, 1995; Rossi, 2001).

For purposes of this report, community is defined as any group of people who share geographic space, interests, goals, or history. A community offers a diversity of potential targets for prevention and is often conceived of as an encompassing, proximal, and comprehensive structure that provides opportunities and resources that shape people’s lifestyle (McIntyre and Ellaway, 2000). A community also offers the potential for pooling resources and for collaboration among community-based organizations, some of which are affiliates of state and national organizations that can channel resources to them in support of local initiatives and the evaluation of their innovations (Kreuter et al., 2000).

A distinction can be made between community-based prevention and community-placed prevention, or community interventions versus interventions in communities (Green and Kreuter, 2005), although both take a population-based approach. Community-based activity involves members of the affected community in the planning, development, implementation, and evaluation of programs and strategies (Cargo and Mercer, 2008). An example of this type of prevention effort is community-based participatory research, in which academic researchers—who are usually in control of the decisions on the research question, design, methods, and interpretation of results—invite or concede at least an equal partner role to community members in formulating, conducting, and interpreting the research. It is important to note that rarely are all members of a community involved and that for those who are, the level of involvement can vary tremendously.

Community-placed activities, on the other hand, are developed without the participation of members of the affected community at important stages of the project. While the program may be centrally planned, effort is expended to generate community support. An example of the community-placed approach is the YMCA diabetes prevention program that is being implemented in partnership with YMCAs across the country, some with more tailoring to the localities than others (Ritchie et al., 2010).

Although there are distinct differences between these two approaches to prevention, for purposes of this report key domains for valuing (discussed in Chapter 3) are common to both approaches. Therefore, the term “community-based prevention” is used to encompass both community-placed and community-based prevention programs, policies, and strategies.

IMPORTANT FEATURES OF COMMUNITY-BASED PREVENTION

Over the past 50 years public health practice and research have contributed to developing and analyzing the characteristics that distinguish community-based prevention from other forms of action. Community-based prevention interventions focus on population health and, in addition,

may address changes in the social and physical environment, involve intersectoral action, highlight community participation and empowerment, emphasize context, or include a systems approach.

Community-based prevention is not focused on changing individual characteristics. Rather, the focus is on population health, that is, on “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group” (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003). For example, implementing nutritional standards for a population is a community-based prevention intervention. Such standards require decision making by a school district and their development may include elected officials, parents, administrators, and students. They affect all of the students and parents in the school district. An individual buying a Stairmaster and using it at home is also taking part in a nonclinical prevention program, but it is not community-based. The owner of the Stairmaster need not consult the neighbors before purchasing it, nor are the neighbors helped by the purchase.

Changes in social and physical features of the environment constitute valued outcomes for community-based prevention because the distributions of risk factors, health outcomes, and wellness indicators in a population are largely shaped by social and physical environments. Research has shown that social characteristics such as socioeconomic status, social cohesion, social capital, and friendship networks are associated with health and well-being (Adler et al., 2008; Berkman and Kawachi, 2000). The same is true for such features of the natural and built physical environment as poor housing, increased levels of pollution, the presence of green spaces, quality of housing, the safety and pleasantness of the walking infrastructure, and many others (Gauderman et al., 2004; Handy, 2004; IOM, 2000a; Kawachi and Berkman, 2003; Nelson et al., 2006).

Research also has demonstrated that intersectoral action is an important component of interventions aimed at population health (Gibson et al., 2007; Kreisel and Schirnding, 1998). Intersectoral action refers to engaging and coordinating actors from a variety of relevant sectors in the planning, implementation, and governance of interventions. Because most of the social and environmental determinants of population health exist outside the sphere of influence of the health sector, such intersectoral partnerships are key processes by which changes in the main determinants of health can happen (Gibson et al., 2007).

The health in all policies (HiAP) approach to address the social determinants of health encourages governments to include multiple sectors (e.g., taxation, education, transportation) in programs and policies to improve population health (WHO, 2010). Examples can be found in the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report that examined the role of laws and other policies on the public’s health. That report endorsed the potential of HiAP in population health improvement and provided examples of local, state, and

federal-level collaboration among different sectors, including transportation, planning, and community development (IOM, 2011). The report also described a continuum of applications for HiAP, ranging from “do no harm” (i.e., consider the health effects of proposed policy in non-health areas) to a proactive approach to addressing the most distal determinants of health. Finally, the report recommended local planning processes modeled on the structure and role of the National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council, and designed to engage a variety of external stakeholders.

Community participation refers to the engagement of those affected in the process of transforming those conditions that influence community health. Participation can occur at various stages of the project and can also vary in intensity. It can involve the affected individuals themselves or spokespersons for them. In community interventions, participation often translates into volunteer work and other local resources that increase the potential intensity of the intervention.

Adapting community-based interventions to local conditions and context is an important feature of effective interventions and increases community ownership and buy in for the intervention (McLaren et al., 2007). However, it is insufficient to assume that community participation will result in change. Change is dependent on who participates and varies as leadership changes. Many times it is the “squeaky wheels” that persist and carry the day whether they are representative or not. These processes take a long time during which many things change, including broad secular changes like the local economy, leadership, availability of funding, etc. While engagement is indeed relevant to successful interventions, it is important to be aware that it is no panacea.

Empowerment refers to the ability of individuals or groups to exercise control over the conditions and circumstances that influence health and well-being. Intervention processes that promote empowerment and capacity development are also often participatory (Dressendorfer et al., 2005; Israel et al., 1994). It has been demonstrated that collective empowerment enables communities to better identify and solve their problems through more efficient processes of assessing needs and advocating for policies (Edmundo et al., 2005; Reininger et al., 2005).

The context within which community-based prevention is developed and implemented is also important. Intervention means there is an interruption of the normal evolution of events or trajectory, sometimes from outside the community. This outside trigger may be a funding opportunity or a policy or administrative initiative from another level of government or organization that resides outside the community of interest. Funding opportunities may come from various sources and be associated with other types of resources, such as access to technical expertise and knowledge. These triggers are external resources that can be invested in the solution

of a problem or in the improvement of local conditions. Alternatively, the outside event might be a global or national trend, such as global warming or a pandemic that is threatening local communities.

Effective mechanisms for community-based prevention do not, however, reside solely in the external resources that constitute or support the intervention. Characteristics of the community in which the intervention will be implemented interact with those resources and include the cultural, social, political, and physical characteristics of the populations that are targeted by the intervention. These characteristics may also be transformed through the intervention process, increasingly blurring the distinction between the intervention (in the sense of the effective transformative mechanism), context, and intervention effect.

A systems approach is the final feature discussed here. (For more on the systems approach, see Chapter 3.) Comprehensive community-based prevention efforts provide for a combination of interventions that predispose, enable, and reinforce the behavioral and social changes that individuals and organizations need to make in order to successfully achieve health outcomes (Green and Kreuter, 2005; Wagner et al., 2000). They also encompass multiple sectors and multiple levels, as with state-level mass media and the local tailoring of interventions.

Community-based prevention efforts aimed at addressing the living and working conditions that affect health are not new. As discussed in Chapter 1, the major causes of morbidity and mortality in the 19th century were communicable diseases. Early attempts to control these diseases focused on community-based prevention aimed at improving personal hygiene, housing and sanitary reforms, and laws to improve living conditions among poor urban dwellers. Other efforts focused on improving food and workplace safety. Population health in the United States improved dramatically because of these community-based efforts. As a result of these efforts as well as improvements in clinical prevention, chronic diseases and injuries have replaced communicable diseases as the leading causes of illness and mortality in the United States.

Just as the major causes of morbidity and mortality have changed, so too has our understanding of health and what makes people healthy or ill. In 1974 Marc Lalonde, Minister of National Health and Welfare Canada, presented a white paper that laid out the perspective that health is influenced by environment, lifestyle, human biology, and health care organization. Evans and Stoddart (1990) presented a more complex model of the determinants of health which included behavioral and biological responses to both the social and physical environments. The report Gulf

War Veterans: Measuring Health (IOM, 1999) proposed a framework for health that described how individual and environmental characteristics influence health-related quality of life. And a list of major health determinants assembled by Kaplan and colleagues (IOM, 2000b) included pathophysiological pathways, genetic and individual risk factors, social relationships, living conditions, neighborhoods and communities, institutions, and social and economic policies. In 2002, the IOM report The Future of the Public’s Health developed a new model, adapted from Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991), that presented an ecological view of the determinants of health, discussed later in this chapter.

Research has documented the important effects that social determinants have on health, both directly and through their impact on other health determinants, such as risk factors (Berkman and Kawachi, 2000). It has long been known, for example, that people with greater socioeconomic status are healthier than those with lower status; that those with social support fare better, both physically and mentally, than those without; and that one’s neighborhood and built environment affect one’s health (Adler et al., 2008; Antonovsky, 1967; Berkman and Glass, 2000; Cohen et al., 2000; Eller et al., 2008; Kawachi and Berkman, 2001, 2003; Marmot and Wilkerson, 2000; Stansfeld et al., 1999). Such inequalities highlight the importance of focusing on social determinants when intervening to improve the health of individuals and communities.

In 1990, McGinnis and Foege (1993) estimated more than 50 percent of the deaths in the United States each year can be traced to tobacco use, alcohol consumption, a sedentary lifestyle, and a diet heavy in salt, sugar, and fat and low in fruits and vegetables. A later analysis by Mokdad and colleagues (2004, 2005) found that for the year 2000, 18.1 percent of U.S. deaths were attributable to tobacco, 15.2 percent to poor diet and physical inactivity, 3.5 percent to alcohol consumption, and other percentages, in decreasing order, were attributable to microbial agents, toxic agents, motor vehicle crashes, incidents involving firearms, sexual behaviors, and illicit use of drugs. Targeting interventions toward the conditions associated with today’s challenges to living a healthy life requires an increased emphasis on the factors that affect these causes of morbidity and mortality, factors such as the social determinants of health.

Recent work in community-based prevention has also sought to address the distribution of health and risk factors in populations through programs, policies, and strategies that attempt to reduce social inequalities—or to mitigate their effect on health—and to strengthen the cultural assets of all groups (Bleich et al., 2011). Several approaches to health behavior change, discussed below, have contributed to the way in which current community-based prevention efforts are planned and implemented to address not only

population-wide change, but also a reduction in the disparities among social groups.

Health Behavior Change

The U.S. Agricultural Extension Service produced a model of community diffusion and adoption of innovations that continues to inform and guide the planning of community health behavior programs (Brownson et al., 2012; Green et al., 2009; Lionberger, 1964; Rogers, 2002). At the level of individual behavior change, the diffusion model evolved to represent stages in the innovation-diffusion process. The translation of this model to community-based prevention has generally taken the form of interpreting each stage in the individual adoption model relative to the community supports it might need or the community efforts required to facilitate each phase (Rogers, 2002), as illustrated in Table 2-1.

A model for community-based prevention developed in the 1950s and 1960s grew out of efforts to increase both immunization coverage for mass poliomyelitis protection and mass screening for cancer and tuberculosis (Deasy, 1956; D’Onofrio, 1966; Hochbaum, 1956, 1959). This model, the Health Belief Model, was primarily a psychological model developed from community screening and immunization programs, but it became a part of community intervention models in that it provided a guide to planning the mass media component for recruitment of people for screening or immunization in community programs (Becker, 1974; Harrison et al., 1992; Janz and Becker, 1984).

Another development in the 1960s, which accompanied President Kennedy’s New Frontier initiative and President Johnson’s Great Society,

TABLE 2-1 Features of the Organization or Community Supporting States of the Individual Change Process

|

|

|

| Phase in Psychological Process of Change | Supporting Features of Community |

|

|

|

| Exposure | Social setting with access to media |

| Attention | Interest of family, peers, and other significant persons |

| Comprehension | Group discussion and feedback, question and answer sessions |

| Belief | Direct persuasion and social influence, actions of informal leaders |

| Decision | Group decision making, public commitments, and repeated encouragement, which build self confidence |

| Learning | Demonstrated and guided practice with feedback and continued confidence, advice, and direct assistance |

|

|

|

| SOURCE: Green and McAlister, 1984. | |

War on Poverty, and civil rights initiatives, was the promotion of public participation in community health planning. Each legislative act of those initiatives carried the phrase “maximum feasible participation,” which required 51 percent of the planning boards for local program entities to be nonprofessional residents of the community. Insufficient funding for these efforts, however, produced understaffed community agencies and programs. This led many of the agencies and programs to turn to their volunteer community planning participants to help staff the organizations. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (1969) referred to this as “maximum feasible misunderstanding” of the participatory principle. Citizen participation in planning community programs fell into some disrepute as a result, but the stage was set for a later revival of participatory principles in community health assessments, planning, research, and evaluation (Green, 1970b, 1986b).

In the 1970s and 1980s, as the growing experience with multisector community approaches took form with community health planning and regional medical programs, the principle of participation evolved from one emphasizing the generation of community support for centrally planned programs to a principle of involving the community in planning programs locally (Green, 1986a). As described by Hackett (1982), “It was from such principles that the modern strategy of community health in countries arose, which was adopted and put into practice by the World Health Organization and was presented at the Alma Ata Conference on Primary Health Care in 1978.”

These moves away from individually focused clinical prevention strategies were not yet penetrating the chronic disease control field, however. In the 1970s the first trials aimed at reducing the prevalence of behavioral risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) were based in clinical settings and were directed at patients who were at risk of developing CVD. For example, the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) randomly assigned about 13,000 men at high risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) either to usual care and medical follow-up or to a series of prevention interventions. However, the prevention interventions mainly consisted of the medical control of high blood pressure, smoking cessation sessions, and dietary counseling for lowering cholesterol level. Although the experimental group showed improvements in the prevalence of risk factors, notably reductions in smoking, such improvements were not significantly different from those observed in the control group. One hypothesis for this minimal difference was that community and mass media activities addressing these risk factors were taking hold, resulting in pervasive exposures of the control groups to influences as strong as the clinical interventions (Green and Richard, 1993).

While clinical approaches have important contributions to make in addressing risk factors, community-based prevention programs have three distinct strengths:

- Community-based prevention is aimed at and implemented in a population. Therefore, all members of that population have access to the intervention. Clinical services, however, reach only those individuals who can afford and seek clinical services.

- Because community strategies are directed at a population, they can reach individuals with varying levels of risk and, in particular, the large group of people who generally fall in the middle of a bell-shaped curve (Rose, 1992). Clinical services tend to be directed at changes for the relatively smaller number of high-risk individuals, those at the high end of the curve. This means they do not prevent individuals who are at lower risk from developing behaviors and lifestyles that will put them at higher risk (Syme, 1994).

- Lifestyle and behavioral risk factors are shaped by environmental conditions that are not necessarily under the direct control of individuals or of their physicians (Cockerham et al., 1997; Frohlich et al., 2001; Kawachi and Berkman, 2003). Community-based prevention programs can be designed to affect environmental and social conditions that clinical services cannot.

The Settings Approach

As discussed above, clinical prevention alone is insufficient to modify behavioral risk factors at the level of populations. Complementary community-based prevention programs and policies can be implemented in workplaces, schools, families, and communities (Poland et al., 2000). Some settings (such as schools) provide a more or less captive pool of identifiable individuals who can be reached easily with an intervention as long as it does not require modifying environmental conditions (Richard et al., 1996). School immunization programs in which school registries and classrooms are used for the identification, gathering, and vaccination of children are an example of such prevention interventions in schools. By contrast, other interventions are designed to modify a setting’s physical and social environmental conditions that influence the prevalence of risk factors. Prominent examples have been workplace bans on smoking, which protected workers from the secondhand smoke of other employees or of customers and also began to change norms about the acceptability of smoking in public places. Similarly, the banning of unhealthful products from vending machines in schools, and the construction of bike paths in urban areas has improved the health environments of children and adults.

APPROACHES TO COMMUNITY INTERVENTION

It is beyond the scope of this report to offer a full review of the approaches to community-based prevention aimed at altering the distribution of disease risk factors. However, this chapter does explore four categories of such efforts: the ecological approach, social marketing and public health education, health promotion, and policy change. Community-based prevention programs that combine these four approaches can produce systems changes that are comprehensive and that exhibit significant and durable effects on a population. For more discussion about systems, see Chapter 3.

Ecological

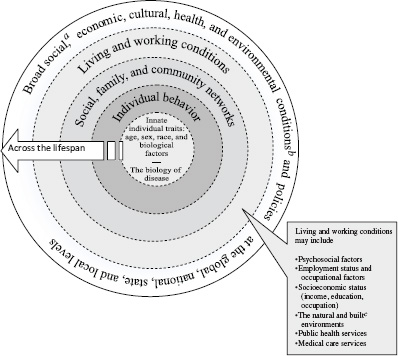

The first group of strategies is based on an ecological model of public health interventions. An ecological model (Figure 2-1) published in the report Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?: Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century “assumes that health and well being are affected by the interaction among multiple determinants including biology, behavior, and the environment” (IOM, 2003, p. 32). A recognition of the multiple determinants of health, including the importance of the social and environmental determinants, is a key feature of the ecological approach. For community-based prevention interventions using the ecological approach, the interaction between levels of influence creates multiple opportunities for designing interventions to affect successive levels of the community structure (McLaren and Hawe, 2005). Various ecological models have been developed which incorporate concepts such as resources, social ecology, the life course and learning processes, and social context in order to demonstrate how the environment shapes individual behavior (Richard et al., 2011).

In addition to the development of interventions aimed at changing individual behaviors, the ecological approach can also be applied to affect collective behavior, organizational behavior, and the reciprocal relationship between the various levels via constraints and resources embedded in the structural features of the socio-cultural context (Stokols, 1992). Such a perspective integrates the approaches of individual behavioral interventions and interventions affecting the physical environment in an effort to focus action on the social environment to account for the needs of individuals and the resources available to address those needs (Stokols, 1996; Stokols et al., 1996). Several distinct uses of the ecological perspective have been described in the public health literature (IOM, 2003). They emphasize the need for interventions to target the various systems that influence behaviors (McLeroy et al., 1988; Richard et al., 1996; Stokols, 1996).

FIGURE 2-1 A guide to ecological planning of community prevention programs. NOTE: The dotted lines between levels of the model denote interaction effects between and among the various levels of health determinants (Worthman, 1999).

a Social conditions include, but are not limited to, economic inequality, urbanization, mobility, cultural values, attitudes, and policies related to discrimination and intolerance on the basis of race, gender, and other differences.

b Other conditions at the national level might include major sociopolitical shifts, such as recession, war, and governmental collapse.

c The built environment includes transportation, water and sanitation, housing, and other dimensions under the auspices of urban planning.

SOURCE: Adapted from Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991.

Social Marketing and Public Health Education

Social marketing and education are strategies that seek to change people’s knowledge and attitudes about health, risk factors, and determinants. At the most basic level, prevention interventions seek to increase people’s awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about chronic disease risk factors and lifestyle based on the premise that knowing what is good for oneself is a necessary first step for behavior change. Such interventions work best when they focus in the short run on a single issue or behavior or else on a small set of interrelated disease-specific risk factors (e.g., Eriksen et al., 2007). (One notable exception is school health education, which has traditionally sought to build a cohesive body of personal health knowledge and competence.) Awareness and attitude-change programs in public health education have increasingly adopted the principles of social marketing, which is understood as a “process for influencing human behavior on a large scale, using marketing principles for the purpose of societal benefit” (Smith, 2000). The National Social Marketing Center in England defines social marketing as “the systematic application of marketing, along with other concepts and techniques, to achieve specific behavioral goals for a social good” (French, 2009; Reynolds, 2012).

A key feature of social marketing is the segmentation of the target group into individual homogenous audiences each with similar attitudes and beliefs (Diehr et al., 2011). Common bases for segmenting the target audience include attitudes, behaviors, demographics, epidemiology, geography, psychographics,1 motives and benefits sought, and the stage of readiness for change (Donovan et al., 2010). In public health, social marketing has been conceptualized as a way to tackle the limitations of individual and small-group counseling and as a means to reach a broader segment of the population with simplified “products” (i.e., concepts) based on educational messages for behavior change (Lefebvre and Flora, 1988). In the United States and other Western countries, social marketing has been used for antismoking campaigns as well as to promote physical activity, to reduce levels of cardiovascular disease, and to prevent substance abuse.

Social marketing strategies have shown promising results in encouraging exercise, improving diet, and addressing substance misuse (Gordon et al., 2006). The LEAN (Low-fat Eating for America Now) national social marketing campaign of the Kaiser Family Foundation demonstrated that successful social marketing efforts are built on scientific consensus and include a broad range of partners from the public and private sectors as well as professional associations based on collaborative agreements (Samuels,

____________________

1 Psychographics is “market research or statistics classifying population groups according to psychological variables (as attitudes, values or fears).” See http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/psychographics (accessed May 21, 2012).

1993). Although necessary to trigger community transformation processes, social marketing, awareness raising, and attitude change by themselves have long been recognized as insufficient to induce changes in most segments of the population (Green, 1970a). More comprehensive strategies are needed to address the various barriers to, and enablers of, behavioral and social changes.

Health Promotion

Health promotion approaches are different from social marketing approaches in that they engage people and organizations in the transformation process and that this engagement in the process constitutes in itself a desired change. Health promotion conceptualizes health as a product of everyday living and proposes values and principles for public health practice (Breslow, 1999; Kickbusch, 2003; Potvin and Jones, 2011). These values are outlined in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion as the basis for strategies to promote health and well-being through the reorientation of health services, healthy public policy and intersectoral action, community action, the development of personal skills, and the creation of healthy environments (WHO, 1986). While improved health and well-being are goals of health promotion, the guiding principles for health promotion initiatives are that they should be “empowering, participatory, holistic, intersectoral, equitable, sustainable, and multi-strategy” (Rootman et al., 2001).

The goals of health promotion initiatives are generally defined in terms of increasing the capacity of individuals and communities to control of their health and its determinants (Nutbeam, 1998b). Health promotion outcomes include health literacy, social action and mobilization, organizational change, and healthy public policy. These outcomes are viewed as having their own intrinsic value as well as being instrumental in achieving intermediate health outcomes and, ultimately, broader health and social outcomes (Nutbeam, 1998a).

Policy Change

The final approach involves changing the public policies that govern the lives of citizens in a given jurisdiction. Public policies are broadly defined by actions taken by a government in the pursuit of its vision of the public good. Policies are “the whole set of solutions initiated by public authorities” (Bernier and Clavier, 2011). Public policy occurs at various levels of jurisdiction—local, regional or state, national, and global—and it can take various forms. The report Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research (IOM, 2000b) proposes five types of action through which governing bodies can use laws and policy to achieve health

and safety. The first is to use taxation to create economic incentives and disincentives intended to shape consumers’ behaviors. Examples include taxes on products such as tobacco or alcohol (e.g., Elder et al., 2010; Hopkins, 2001; Hopkins et al., 2001; Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2005).

The second type of action is to influence norms and values through the informational environment, using social marketing as a strategy. This is often a first step in a progression toward full regulation. Social marketing campaigns on the benefits of seat-belt use paved the way for the enactment of direct regulation to impose sanctions on car passengers who did not buckle up. As such regulatory measures came into being, their enforcement with highway spot checks of seat-belt wearing was enhanced in its effectiveness by mass media publicity about the citations and fines being given for failure to have seat belts fastened (Vasudevan et al., 2009).

The third type of action is direct regulation of specific risky behaviors that makes those behaviors unlawful and penalizes them, for example laws prohibiting the use of cell phones while driving or smoking by individuals under age 18.

Fourth, indirect regulation consists of “actions taken by legislatures and administrative agencies to prevent injury or disease or to promote public health” (IOM, 2000b, p. 398). An example is the addition of fluoride to water to prevent dental caries.

The fifth type of action, deregulation, is the alleviation of laws in the interest of the public’s health. For example, laws prohibiting bicycles on some roadways could be repealed if bike paths and sidewalks were constructed on those roadways, thereby facilitating more physical activity and less pollution.

Once one recognizes that many determinants of health are outside the health sector and that those determinants can be influenced by policy, influencing the content and process of public policy becomes a strategy for promoting health and wellness. This is especially true at the community level. For example, to challenge industry practices it is generally easier to pass local ordinances than to enact legislation at the state or national level, where legislative proposals can more readily be challenged by industry lobbies.

A public policy is much more than a document or a given piece of legislation (Bernier and Clavier, 2011). It is a product of the interplay between political actors and citizens who use their power and resources to influence the process of setting the policy agenda, defining the policy content, and mobilizing resources for its implementation (Hassenteufel, 2008). Policy making is thus best conceived of as a dynamic process that involves a spectrum of stages in iterative cycles: agenda setting, policy formulation, decision making, policy implementation, and policy evaluation (Howlett et al., 2009; Ottoson et al., 2009). Various opportunities to influence the

policy process present themselves at various stages in the cycle. Public health enters the agenda-setting stage of the public policy process, linking products or living conditions to health outcomes.

The long evolution in tobacco legislation throughout the second half of the 20th century offers an example of all the different policy approaches used together. Starting with the scientific recognition of the negative health impact of tobacco smoking in a public health report in 1964, and moving to various bans on tobacco in public places and increasing taxes on tobacco products, the history of tobacco policy in Western countries has shown that even in the face of valid scientific evidence, influencing the policy-making process is a work of advocacy and political influence, building coalitions, staging the public debate, evaluating comprehensive statewide and community policies and programs, and disseminating the findings of those evaluations to other jurisdictions (Bernier and Clavier, 2011; Breton et al., 2008; Eriksen et al., 2007). Studies of the policy process have shown that such efforts require resources and work because the political arena is occupied by powerful actors who promote and finance divergent interests and because scientific evidence alone is insufficient. People have to understand it, be persuaded by it, and change their thinking to incorporate it.

Recognizing that many determinants of health are the responsibility of sectors of public administration other than health, the Health in All Policies project aims to equip public health practitioners with a rationale to partner with other sectors in the pursuit of a variety of policy objectives that do not directly affect health but whose impact on the determinants of health is well documented (WHO, 2010). A case in point is the advocacy role of public health for urban planning models that create more opportunities for active transportation under the rationale that any commuting strategy that does not involve the use of a car increases the daily level of physical activity. Other examples may be found in the 2011 IOM report For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges.

The following section contains brief descriptions of four models of program planning, implementation, and evaluation. These models are offered as illustrative examples of various conceptual and organizational frameworks used in the field of community-based prevention. The first model, PRECEDE–PROCEED, differs from the others in that it also contains a decision-making component. For this reason, the PRECEDE–PROCEED model is also discussed in Chapter 4. The other three models in this section are used by planners to implement changes after needs have been assessed and priorities established. These models are not used for valuing or choosing between interventions.

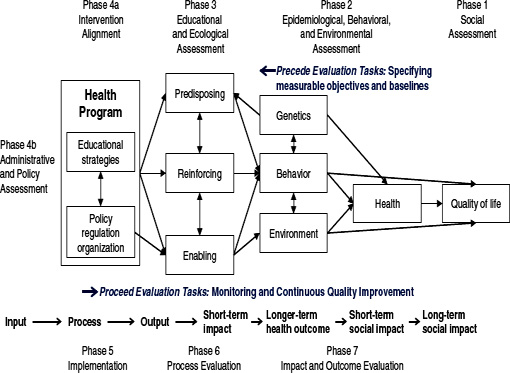

PRECEDE–PROCEED

The PRECEDE–PROCEED is a planning and evaluation model that evolved over more than four decades and four book editions (Green and Kreuter, 2005). Initially designed as a health education model, PRECEDE–PROCEED currently integrates several strategies to transform the ecosystem of individual well-being. Elements of the ecosystem that are amenable to transformation are the environment, health, lifestyle, and quality of life (Figure 2-2). A mix of educational, advocacy, policy, regulatory, resource-mobilizing, and organizational strategies are used to modify the predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling factors of the ecosystem. This model has been widely used in planning and evaluating community- and settings-based health programs (see http://www.lgreen.net/bibliography.html).

Other models such as MATCH (Multilevel Approach Toward Community Health; Simons-Morton et al., 1988c), PATCH (Planned Approach to Community Health) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (HHS, no date; Kreuter et al., 1997), and intervention mapping (Bartholomew et al., 2001) also build on and extend the PRECEDE–PROCEED model with the provision of federal and state consultation processes and more detailed mapping of theory onto interventions.

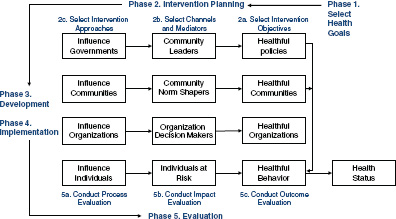

The Multilevel Approaches Toward Community Health Model

The Multilevel Approaches Toward Community Health (MATCH) model (Figure 2-3) provides a representation of the ecological levels in conjunction with the planning, implementation, and evaluation stages of a community organization process.

The MATCH model was developed by Simons-Morton and colleagues (Simons-Morton et al., 1988a,b,c, 1989, 1991, 1995) for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for use in intervention handbooks to assist communities in the planning and evaluation of community programs. It is an intervention model aimed at influencing health at three levels: individual, organizational, and governmental. Its developers characterize MATCH as an “organizing framework” designed to be applied after risk factors and priorities for action have been identified (Simons-Morton et al., 1988c).

The model originally consisted of four phases: health goals selection, intervention planning, implementation, and evaluation. Each phase has multiple components that give the model the flexibility to be adapted to the context of the target population, community, or intervention. It can be used for a variety of interventions, from strategies to improve hypertension medication compliance to population-level interventions aimed at preventing injuries, such as programs to increase seat-belt use.

FIGURE 2-2 PRECEDE–PROCEED model.

SOURCE: Green and Kreuter, 2005.

FIGURE 2-3 MATCH model.

SOURCE: Simons-Morton et al., 1995.

The selection of health goals can be based on a number of factors, ranging from epidemiological data to community preference or the personal interest of an individual. The second and third phases, intervention planning and implementation, can be targeted at either the individuals or communities whose health is affected or at those whose funding or policy decisions affect these individuals or communities. Each intervention has varying approaches and intensities and can therefore be tailored to the needs of the target group. Finally, the intervention is evaluated based on process, impact, and outcome. The evaluation determines whether the intervention led to progress toward the health goals identified in the first phase. This includes, in the case of the interventions aimed at organizations or governments, whether the intervention led to other interventions (Simons-Morton, 1988).

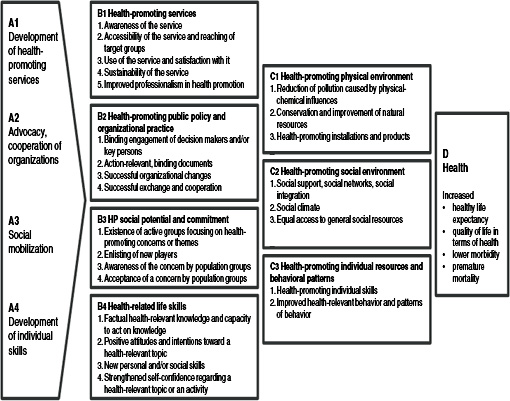

The Swiss Model for Outcome Classification in Health Promotion and Prevention

The Swiss Model for Outcome Classification in Health Promotion and Prevention (SMOC) is a planning and evaluation tool developed by Health Promotion Switzerland and the Institutes for Social and Preventive Medicine in Bern and Lausanne to aid in health promotion efforts. The model is intended to be broadly applied and to provide an overview of activities for planners and evaluators. It also establishes a common language to ease communication among stakeholders, and it helps with determining

objectives and indicators. Originally developed for use with individual projects, SMOC has also proven useful for higher-level planning (Spencer et al., 2008).

The SMOC model is based on the work of Nutbeam (2000), which presented an outcome model for health promotion activities (Nutbeam, 2000; Spencer et al., 2008). The Nutbeam model moves from health promotion actions through health promotion outcomes and intermediate health outcomes to health and social outcomes measured by, among other things, morbidity, mortality, and disability. Nutbeam attempts to provide a bridge between the intervention and its goals, listing potential measures of progress between the two (Nutbeam, 2000).

SMOC (Figure 2-4) builds on this concept. It contains four levels: health promotion measures (A), factors influencing health determinants (B), health determinants (C), and health status (D). Within the four levels are 16 categories that provide further detail and guidance to users of the model. It is important to note that there are no arrows in the model. Although it is clear that each level has an impact on the subsequent level, the lack of arrows acknowledges that each level or category can provide feedback or have an effect on any other part of the process without the sequence of effects necessarily being linear. This flexibility is intended to make the model adaptable in dealing with real world situations and a wide range of stakeholders (Spencer et al., 2008).

The Community Development Model

The community development model includes three important concepts: decentralization, participatory planning and implementation of programs, and multisectoral involvement. Ideally, decentralization places the planning and evaluation functions at the local level and keeps the highly specialized resources, including expensive technology and facilities, at the central level. The effective delivery of community development programs necessarily depends on both central and local organizations.

The participatory planning and implementation aspect of the model, which applies both to organizations and individuals, involves people in an affected community setting their own priorities and goals and planning out programs that will serve them. Expecting neighborhoods and organizations to implement programs planned elsewhere often yields only limited local commitment to the goals and methods of the program (Bracht, 1998; Rothman and Brown, 1989). Efforts that involve community participation often require a longer time for planning and coordination because of the need to enlist the cooperation and participation of members of the community (Green, 1986a,b).

FIGURE 2-4 Overview of the Swiss Model for Outcome Classification in Health Promotion and Prevention.

SOURCE: Spencer et al., 2008.

Multisectoral involvement is the inclusion of representatives from a variety of sectors that can help effect change. Often such inclusion takes the form of a coalition, which might include representatives from recreation, business, media, and welfare sectors as well as from medical and health sectors. Coalitions have the value of bringing multiple stakeholders together to agree on goals and broad strategy. Many organizations outside the health field have taken up health-related programs because they perceive a public demand for health promotion, better health protection, or health service. Commercial interests, in particular, have risen to the challenge of consumer demand. As Kickbusch and Payne (2003) observed, “[I]n the United States alone the sales of the wellness industry have already reached approximately $200 billion, and it is set to achieve sales of $1 trillion within 10 years.”

The community development model has been widely applied, albeit with varying success. Pilot projects in Toronto and California inspired the Healthy Communities efforts in both Canada and the United States. The World Health Organization promoted the Healthy Cities movement to encourage city governments to take a broad, multisectoral approach to planning for health promotion. Underlying the approach is the ecological model discussed earlier, that is, a broad view of the determinants of health, including policies and environmental conditions that influence the health of whole populations. The community development model emphasizes the disparities in health and the need for more equitable distribution of health-related resources to close the gaps between subpopulations.

Recent applications of the community development model in Australia, Europe, and Canada have been carried out under the Healthy Cities and Healthy Communities initiatives (Inayatullah, 2011; Larsen and Manderson, 2009). In the United States, community development in health has occurred under the Planned Approach to Community Health (PATCH) model. PATCH was first developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1983 as a way of reconciling federal funding requirements, which were locked into specific disease categories, with the community development principles of local planning for needs that communities themselves identify. The designers of PATCH based their approach on the traditions of state and community capacity-building and data-based planning and monitoring of programs. The PRECEDE–PROCEED model of planning and evaluation along with community development principles of local ownership were applied in PATCH (Green and Kreuter, 1992). By 1987, 25 PATCH programs had been initiated in 12 states, and by 1997 several hundred were under way across the United States (Kreuter, 1992). Dozens more programs were modeled after this approach in Australia, Canada, China, and Europe.

IMPACT OF COMMUNITY-BASED PREVENTION

As discussed earlier, community-based prevention can involve complex systems of coordinated actions which include numerous actors, many acting in concert through organizational partnerships and coalitions. Ideally the partnerships include intersectoral collaboration between health organizations and their public-sector counterparts in education, social services, and city planning as well as private-sector business interests that influence the diets, physical activity, tobacco consumption, and other behaviors of the public that affect health. Evaluation seeks to determine the effectiveness of these efforts; it poses many methodological and practical problems because of the complex and systemic nature of community-based prevention (Mercer et al., 2007).

A frequently cited example of community-based prevention is the North Karelia study in Finland (Puska and Uutela, 2000; Puska et al., 1985, 1998). This was a grassroots initiative, begun in 1972, aimed at reducing the community’s high rates of death from coronary heart disease (the highest in the world at that time). Local authorities consulted with and received technical assistance from researchers in formulating and implementing the project. Initially, the main focus was improving dietary habits and reducing rates of smoking, but these goals were later enlarged to include the broader objectives of chronic disease prevention and health promotion in both children and adults. Box 2-1 provides a summary of the project’s achievements.

Key features of the program were

- a carefully outlined theoretical framework;

- community involvement;

- a flexible and dynamic intervention, adapting to naturally occurring events;

- a multifaceted intervention, including innovative media campaigns, health care providers, environmental changes, and industry and policy changes; and

- strong leadership and institutional support.

The North Karelia project inspired efforts sponsored by the National Institutes of Health to implement and evaluate similar community interventions in California with the Stanford Three-Community and the Stanford Five-Community studies. In a series of commentaries and editorials published following the release of disappointing results, leading epidemiologists acknowledged the limitations of the controlled experiment to assess the value of such interventions on a community scale (Fisher, 1995; Fortmann et al., 1995; Suser, 1995; Winkleby, 1994; Winkleby et al., 1996).

BOX 2-1

Achievements of the North Karelia Project: 2005/2007

Smoking rates decreased from 52 percent to 31 percent in men, although the rates increased from 10 percent to 18 percent in women.

Mean serum cholesterol (mmol/L) decreased from 6.9 to 5.4 in men (a 21 percent drop) and from 6.8 to 5.2 in women (a 23 percent drop).

Mean blood pressure (mmHg) decreased from 149/92 to 139/83 in men and from 153/92 to 134/78 in women.

Reductions in age-adjusted mortality for men, 35-64 years of age, between 1970 and 1995:

- All causes: 63 percent

- All cardiovascular causes: 80 percent

- Coronary heart disease: 85 percent (this is the most rapid decline in the world to date)

- All cancers: 67 percent

- Lung cancer: 71 percent (1997)

SOURCES: Puska and Uutela, 2000; Puska et al., 2009.

The 9-year Stanford project did show that the blood pressure improvements observed in all cities from baseline to the end of the intervention were maintained during the follow-up in treatment cities but not in control cities. Cholesterol levels continued to decline in all cities during follow-up. Smoking rates leveled out or increased slightly in treatment cities and continued to decline in control cities, but the differences were not significant. Both coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality risk scores were maintained or continued to improve in treatment cities while leveling out or going back up in control cities (Winkleby et al., 1996).

Reviews by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services as well as the Cochrane reviews have synthesized evidence concerning community prevention efforts. Such syntheses give somewhat mixed results concerning the effectiveness of the interventions. They are useful, however, in providing examples of implementation approaches for community-based prevention. For example, Brinn and colleagues (2010) examined the impact of media and multi-component campaigns to prevent youth from starting to smoke. They identified a total of 84 published evaluations reporting on media campaigns. Unfortunately, only seven of those were conducted using some form of control groups, randomized or not, including time series in which groups were used as their own control with a sufficiently long pre-intervention period and number of observations. Only three of those studies found the

campaign to have helped prevent smoking among people aged 25 years and younger. The effective campaigns were conducted in combination with some school educational activities and used messages developed through extensive formative evaluation. A Cochrane review of multi-component tobacco prevention programs found only 25 controlled trials, only 9 of which reported significant long-term reductions in smoking (Carson et al., 2011).

Among other community interventions, a review of non-legislative interventions to increase bicycle helmet use in children identified four community-based interventions that positively affected helmet use (Owen et al., 2011). Components of the interventions included subsidized helmets, local media campaigns, and helmet education programs. Similarly, in a review of 25 community trials to prevent the uptake of tobacco smoking by youth, Carson and colleagues (2011), identified 10 studies with a significant positive outcome. All successful interventions included a mix of complementary interventions taking place in various community settings, including schools and media campaigns.

The Community Guide to Preventive Services (also known as the Community Guide [www.thecommunityguide.org]) uses systematic, objective, and consistent methods to evaluate evidence for the effectiveness for certain interventions or categories of interventions. Where possible, the Community Guide also reviews evidence of the economic efficiency of the intervention (Briss et al., 2004). An economic evaluation of home-based asthma interventions with an environmental focus was conducted using the methods developed for the Community Guide. For the 13 studies included in the evaluation, the annual total program costs per participant ranged from $231 to $14,858 (in 2007 dollars), depending on the level of environmental remediation carried out in the intervention. Of the 13 studies, annual medical costs averted per participant could be calculated for 6 of them; those annual costs averted ranged from $147 to $10,093 per person. It was possible to calculate incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICER) for only three of the studies; these ranged from $12 to $57 per symptom-free day (Nurmagambetov et al., 2011). Based on this the Community Preventive Services Task Force found that “home-based, multi-trigger, multicomponent interventions with a combination of minor or moderate environmental remediation with an educational component provide good value for the money invested” (see www.thecommunityguide.org/asthma/multicomponent.html).

Three worksite programs to prevent and control obesity reported cost-effectiveness numbers that ranged from $1.44 to $4.16 per pound of weight loss (Anderson et al., 2009). The use of cost-effectiveness per pound of weight loss is an example of the sort of intermediate outcomes that need to be identified in any study that, like this one, is aiming at a very long-term goal (in this case, the prevention of obesity). A review of diabetes self-management education (DSME) programs completed in 2002 found

that there was sufficient evidence of effectiveness to recommend DSME programs be implemented in community gathering places for adults with type 2 diabetes. (Norris et al., 2002) At that time, no studies were found that would permit an economic evaluation of these programs (see http://www.thecommunityguide.org/diabetes/selfmgeducation.html).

In 2011 Thorpe and colleagues estimated that enrolling individuals aged 60-64 who are prediabetic in the YMCA’s community-based diabetes prevention program could save Medicare between $1.8 billion and $2.3 billion over 10 years by averting future medical costs of diabetes in this population (Thorpe and Yang, 2011). Another study that examined Medicare costs between 1997 and 2006 found that the costs were increasing more rapidly for obese Medicare recipients than for those with normal weight (Alley et al., 2012). Finkelstein and colleagues (2009) found that medical costs were higher for obese individuals and that those costs were increasing. They estimated that the rise in obesity prevalence accounted for 89 percent of the increase in obesity spending between 1998 and 2006 (Finkelstein et al., 2009).

Bradley and colleagues (2011) analyzed data on spending for health and social services for member countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). They found that greater spending on social services such as anti-poverty programs, employment programs, and housing support was significantly associated with increased life expectancy, decreased infant mortality, and decreased potential years of life lost. This suggests that there is a link between programs that address the social determinants of poor health and improved population health. Within the OECD, the United States spends nearly twice as much on health care—measured as a percentage of GDP—than other countries, but it ranks in the bottom third in key population health indicators such as life expectancy and infant and maternal mortality (Bradley et al., 2011).

EVALUATION OF COMMUNITY-BASED PREVENTION

For the past 15 years there has been a lively debate in the scientific community about the pros and cons of experimental and observational methods for the evaluation of community interventions (Mercer et al., 2007; Potvin and Richard, 2001). A major issue in evaluating community-based interventions concerns the role of context. The experimental paradigm supposes that interventions are exogenous, that is, that a part of the stimulus and at least some of the support comes from outside of the community and is not created by it. Such exogenous intervention components may take various forms, such as resources (money from a foundation or a federal funding program), knowledge (professional expertise, scientific report, professional practice guidelines based on systematic reviews of evidence), or technical

devices (written curriculum, processed food). Nevertheless, research has shown that to have an effect those external resources must have cultural relevance and to be adapted to local conditions (Tirodkar et al., 2010). Thus the randomized controlled trial that requires a consistent protocol of replication and emphasizes the importance of internal validity (causal certainty) is difficult to use in evaluating community-based prevention interventions.

Another problem for replicability is that the effectiveness of a community intervention is not inherent within the intervention itself (that is, within what is imported from outside). Rather, its effectiveness lies in the interaction between the intervention and the contextual conditions. As a consequence, the actual events and actions that form an intervention in context will differ across various settings, even if the external part of this intervention is held constant (Hawe et al., 2004).

This state of affairs raises a variety of issues from an experimental perspective that presupposes that contextual conditions are controlled for. Even when it is possible to identify objectively the exogenous component of the intervention, systematic observations are needed in order to trace and model the multiple transformations and adaptations such components must go through in order to produce the observable set of unique actions and their impact that characterize a given program. The Kaiser Family Foundation grants program in the 1990s provides an interesting example of a trial that sought to document these interactions between the exogenous components and the community contexts (Wagner et al., 2000). Eleven communities were randomized among qualified applicants to receive funding for a period of 5 years to identify their health needs and develop action plans. Health needs covered a wide range of issues. Community activation was conceived of as an intermediary mechanism that would, because of the activities funded in the selected communities, be elevated compared to a set of 11 comparable communities that did not receive external funding. Results were disappointing, however, as there was no observed difference in community activation between funded and not-funded communities. In terms of health outcomes, results varied and only marginally significant effects were observed for some dietary behaviors in some of the funded communities (Wagner et al., 2000).

This study and another conducted by Hallfors et al. (2002) raise two questions. First, does the outside funding used to initiate a community-organization and coalition-development process create artificial conditions of coalition formation that undercut the effectiveness often attributed to community-initiated coalitions that are not externally initiated (Green and Kreuter, 2002)? Second, might the requirement of outside funding agencies mandating participation through coalitions of multiple organizations rather than through partnerships of a smaller number be a potential detriment to effective community initiative (Green, 2000)?

Changes in communities take time, and for such changes to affect the health of residents it takes even more time. The more distal the targeted risk factors to the health outcome, the more time is required for the intervention to produce effect (de Leeuw, 2011; El Ansari et al., 2001). In addition to the feasibility problems of following communities and (mobile) populations for long periods of time, the long-term nature of community intervention effects makes them more susceptible to interacting with other interventions or historical events, blurring or even dissipating their effect. Researchers and evaluators in health promotion have addressed this problem by creating models of intermediary impact that logically link the intervention to ultimate health and wellness impact (e.g., the models described in this chapter and Chapter 4 and the findings and recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services [http://www.thecommunityguide.org]). These models provide theoretical intermediary checkpoints to assess the direction of changes (if any) associated with the intervention.

In evaluating a community intervention it is critical to be able to link process and outcome evaluation in order to understand how the exogenous components of an intervention interact with local conditions. Such a linking serves the dual purpose of understanding the local adaptations that necessarily take place and of documenting how such programs evolve. Indeed, if interventions are responsive to environmental conditions, it follows that effective interventions will involve and change in response to the changes they produce in community context. Such a dynamic process can only be captured through systematic observations informed by strong theoretical models of change.

Much progress has been made in the conceptualization of community interventions over the past 50 years. One recognized success is in tobacco control (Box 2-2). The science of community intervention is very young and, compared to the historically successful basic sciences, the knowledge base upon which action can be founded contains numerous gaps. The links between the various observations compiled are still very speculative. This is why it is so important to include research and evaluation components in any community-based intervention. Such research is needed to better understand how community interventions work. There exist only a few initiatives worldwide that propose to synthesize the results of evaluations of community-based prevention strategies and wellness policy, including the Cochrane review groups on population and public health, and the CDC-facilitated work of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services.

The Need for More Research and Novel Paradigms

While a few community-based prevention interventions have passed the Community Guide standards for using appropriate methodology for

BOX 2-2

The Case of Tobacco Control Policies as a Template for Successful Community Health Change

Policies and programs work better when they are interdependent and synergistic, as demonstrated by the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health (1999, 2007) and others that have concluded from the successes of statewide and community tobacco control programs that comprehensive tobacco control must coordinate policies and programs that depend on each other for success. Such programs and policies emanate from different levels of organizations and government, and each component reaches different segments of the population. For example, states cannot reach effectively into local organizations, and localities cannot afford the cost of mass media placements.

An informed and concerned public makes it easier to introduce new policies (Green and Richard, 1993). Informational, educational, and motivational messages through various media and channels facilitate awareness and concern. For youth there is a need for mass media to provide a backdrop of messages and images that are consistent with those they receive from family, teachers, and programs. Hollywood film images of smokers who are protagonists and magazine advertisements with images of glamorous models smoking, for example, send an inconsistent message about smoking from those presented in tobacco-cessation programs.

The tobacco industry outspends state tobacco control programs at least $10 to $1, and up to 20 to 1 on media and marketing during political campaigns to raise taxes on cigarettes (Begay et al., 1993; Pierce and Gilpin, 2004; Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee, 2009; Traynor et al., 1993). In the 1970s most political efforts at state and federal levels to ban smoking in public places were successfully beaten back by tobacco industry, but most city and county initiatives to regulate smoking during that same period passed because the industry could not put out the multiplicity of brush fires at the local level (NCI, 2000). Coordinating local and state policy and program efforts has been key to the notable successes of California and other states and municipalities in smoking-cessation efforts (Best et al., 2007; Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee, 2009). When each level of government and voluntary agency action coordinates and divides the labor of comprehensive programs and policies, the synergy produces more successful outcomes.

evaluation, many community-based interventions are implemented without adequate evaluation. This has resulted in a scarcity of information about the effectiveness of these interventions. A number of factors have been identified to explain this relative scarcity, including the small number of evaluations undertaken (as mentioned above), methodological difficulties, and a lack of theoretical clarity.

One set of factors is related to the fact that few interventions are rigorously evaluated, relative to the number of past and ongoing efforts in communities across many countries. There are many more or less defined interventions being implemented by various actors in a community with

various levels of resource investments. Most of these interventions are unknown to all except those directly involved. For example, Spinks et al. (2009) commented that, despite the identification of more than 200 communities worldwide with a WHO Safe Community status, only a handful in two regions of the world have been subject to controlled evaluation. If little is known, it is partly because the issue has not been widely studied.

Another set of factors relates to methodology. Randomized controlled trials, the gold standard in clinical medicine, have proven difficult to undertake for the evaluation of community-based interventions. As discussed earlier, randomized controlled trials require adherence to a set protocol, yet a key characteristic of community-based prevention is to make sure that the intervention is tailored to the affected community, usually with significant input from community members themselves. Such adjustment in the intervention makes it difficult to identify control communities for comparison purposes.

In addition to these methodological difficulties, there might also be a lack of theoretical clarity about the effective mechanisms operating in such interventions and the full range of potential effects that might be influenced by these interventions (Hawe et al., 2004).

Communities have long histories, and their composition in terms of both population characteristics and structural elements is not conducive to rapid change (De Koninck and Pampalon, 2007). Changing the course of such systems is a long-term endeavor and requires a locally valid model of the possible pathways through which such transformations can be spearheaded. Evaluating non-standardized, constantly changing, community-directed, slow-moving changes at all the levels in ecological models from programs to policies presents methodological, logistical, and economic feasibility challenges. It is impossible to determine the relative contributions of all the many moving parts or the active ingredients in the complex interventions (Mercer et al., 2007). Deconstructing complex interventions may not even be advisable, given that ecological models guiding the projects emphasize the need for multi-level interventions and the reciprocal dependency of many of the interventions and policies (Sallis et al., 2008).

The strategic vision of the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) at the National Institutes of Health recognizes that prevailing paradigms focusing on single-cause, single-discipline, and single-level-of-analysis models are necessary but insufficient and calls for interdisciplinary and multilevel approaches that integrate biological, behavioral, and social sciences to address the complex issues that challenge the public’s health (Mabry et al., 2008). Furthermore, the prevailing linear research-to-practice paradigms, while useful for addressing specific clinical or epidemiologic questions, are often inadequate to tackle real-world health

problems that are intrinsically imbedded in the widely varying complexities of behavioral, social, and cultural settings (Livingood et al., 2011).

As with the earlier academically directed intervention studies, however, even when considering these complexities, evaluations of community-based programs, policies, and strategies cannot assure that an effective intervention in one setting will generalize to another community. Emerging paradigms call for the integration of research and practice, similar to the integrations in applied physical sciences, engineering, and architecture (Livingood et al., 2011). These approaches represent a radical departure from best practice interventions and involve the customization of scientific principles and methods to each situation. They offer a greater degree of credibility about their generalizability insofar as they are carried out in real time by real practitioners and community partners (Green, 2007).

The following chapter examines system thinking in greater detail, describing how systems science can be used to explore the complexity of community-based prevention. That chapter also discusses domains of value for community-based prevention interventions.

Adler, N., A. Singh-Manoux, J. Schwartz, J. Stewart, K. Matthews, and M. G. Marmot. 2008. Social status and health: A comparison of British civil servants in Whitehall II with European- and African-Americans in CARDIA. Social Science and Medicine 66(5):1034-1045.

Alley, D., J. Lloyd, T. Shaffer, and B. Stuart. 2012. Changes in the association between body mass index and Medicare costs, 1997-2006. Archives of Internal Medicine 172(3):277.

Anderson, L. M., T. A. Quinn, K. Glanz, G. Ramirez, L. C. Kahwati, D. B. Johnson, L. R. Buchanan, W. R. Archer, S. Chattopadhyay, and G. P. Kalra. 2009. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 37(4):340-357.

Antonovsky, A. 1967. Social class, life expectancy and overall mortality. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 45(2):31-73.

Bartholomew, L. K., G. S. Parcel, G. Kok, and N. H. Gottlieb. 2001. Intervention mapping: Designing theory- and evidence-based health promotion programs. Mountain View, CA: McGraw-Hill.

Becker, M. H. 1974. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, Inc.

Begay, M. E., M. Traynor, and S. A. Glantz. 1993. The tobacco industry, state politics, and tobacco education in California. American Journal of Public Health 83(9):1214-1221.

Berkman, L., and T. A. Glass. 2000. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In Social epidemiology, edited by L. Berkman and I. Kawachi. New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 137-173.

Berkman, L., and I. Kawachi. 2000. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bernier, N. F., and C. Clavier. 2011. Public health policy research: Making the case for a political science approach. Health Promotion International 26(1):109-116.

Best, A., P. I. Clark, S. J. Leischow, and W. Trochim. 2007. Greater than the sum: Systems thinking in tobacco control. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.

Bleich, S. N., M. P. Jarlenski, C. N. Bell, and T. A. Laveist. 2011. Health inequalities: Trends, progress, and policy. Annual Review of Public Health 33:7-40.

Bracht, N. F. 1998. Health promotion at the community level: New advances, 2nd Ed. New York: Sage.

Bradley, E. H., B. R. Elkins, J. Herrin, and B. Elbel. 2011. Health and social services expenditures: Associations with health outcomes. BMJ Quality and Safety 20(10):826-831.

Brennan, L. K. 2002. Community perceptions and physical activity: An examination of the correspondence between protective social factors and behavior. St. Louis, MO: Saint Louis University.

Breslow, L. 1999. From disease prevention to health promotion. JAMA 281(11):1030-1033.

Breton, E., L. Richard, F. Gagnon, M. Jacques, and P. Bergeron. 2008. Health promotion research and practice require sound policy analysis models: The case of Quebec’s tobacco act. Social Science and Medicine 67(11):1679-1689.

Brinn, M. P., K. V. Carson, A. J. Esterman, A. B. Chang, and B. J. Smith. 2010. Mass media interventions for preventing smoking in young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11:CD001006.

Briss, P., B. Rimer, B. Reilley, R. C. Coates, N. C. Lee, P. Mullen, P. Corso, A. B. Hutchinson, R. Hiatt, J. Kerner, P. George, C. White, N. Gandhi, M. Saraiya, R. Breslow, G. Isham, S. M. Teutsch, A. R. Hinman, and R. Lawrence. 2004. Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 26(1):67-80.

Brownson, R. C., E. K. Proctor, and G. A. Colditz. 2012. Dissemination and implimentation science. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cargo, M., and S. L. Mercer. 2008. The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health 29:325-350.

Carson, K. V., M. P. Brinn, N. A. Labiszewski, A. J. Esterman, A. B. Chang, and B. J. Smith. 2011. Community interventions for preventing smoking in young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7:CD001291.

Cheadle, A., W. Beery, E. Wagner, S. Fawcett, L. Green, D. Moss, A. Plough, A. Wandersman, and I. Woods. 1997. Conference report: Community-based health promotion—state of the art and recommendations for the future. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 13(4):240.

Cockerham, W. C., A. Rütten, and T. Abel. 1997. Conceptualizing contemporary health lifestyles. Sociological Quarterly 38(2):321-342.

Cohen, S., I. Brissette, D. P. Skoner, and W. J. Doyle. 2000. Social integration and health: The case of the common cold. Journal of Social Structure 1(3):1-7.

Dahlgren, G., and M. Whitehead. 1991. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies.

De Koninck, M., and R. Pampalon. 2007. Living environments and health at the local level: The case of three localities in the Québec city region. Canadian Journal of Public Health 98(Suppl 1):S45-S53. de Leeuw, E. 2011. Do healthy cities work? A logic of method for assessing impact and outcome of healthy cities. Journal of Urban Health 89(2): 217-231.

Deasy, L. C. 1956. Socio-economic status and participation in the poliomyelitis vaccine trial. American Sociological Review 21(2):185-191.

Diehr, P., P. Hannon, B. Pizacani, M. Forehand, H. Meischke, S. Curry, D. P. Martin, M. R. Weaver, and J. Harris. 2011. Social marketing, stages of change, and public health smoking interventions. Health Education and Behavior 38(2):123-131.

D’Onofrio, C. N. 1966. Reaching our hard to reach—the unvaccinated. Berkeley, CA: California State Department of Public Health.

Donovan, R., N. Henley, and MyiLibrary Ltd. 2010. Principles and practice of social marketing: An international perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dressendorfer, R. H., K. Raine, R. J. Dyck, R. C. Plotnikoff, R. L. Collins-Nakai, W. K. McLaughlin, and K. Ness. 2005. A conceptual model of community capacity development for health promotion in the Alberta Heart Health Project. Health Promotion Practice 6(1):31-36.