The Ohio Innovation Economy in the Global Context

Moderator:

Richard A. Stoff

Ohio Business Roundtable

Mr. Stoff began by thanking the meeting organizers, recognizing in particular Glenn Brown, whom he called “the first true science advisor to a governor and a distinguished scientist and industrialist. He started us on the march in science and technology in the public sector in this state,” he said.

He described the Ohio Business Roundtable as a partnership of chief executives of major businesses that is “committed to working with public leaders to build a stronger Ohio.” He said that the organization was selective in the issues it addressed, advocating “public policies that foster vigorous and sustained economic growth and an improved standard of living for all the citizens of this state.”

Mr. Stoff emphasized his organization’s commitment to “major system change,” and their efforts to serve as a catalyst for change over the last two decades. The Roundtable acts in the belief that knowledge and innovation are the “keys to global competitiveness, and certainly the foundation for economic strength and prosperity.” He noted that several years ago the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, under leadership of Sandra Pianalto, conducted a comparative analysis of the states’ economic strength over the previous 75 years, as measured by relative per capita income growth. The analysis identified two basic variables that differentiated the wealthy states from the less-wealthy. One was innovation, as measured by the pace of technological advance and the strength of commercialization engines. The other was talent, as measured by citizens’ level of education. The Cleveland Fed’s analysis, he said, might be expressed by the equation “innovation plus talent equals prosperity, or I + T = P, with Ohio stuck firmly in the middle of the pack then.”

“At the Business Roundtable,” he continued, “we have used this research over the last several years as our central organizing device.” In developing talent, the group has helped shape statewide education reforms,

primarily in grades K-16, including the “nationally acclaimed” Ohio STEM Learning Network.

Mr. Stoff said that the Roundtable had also “played a major role” in building statewide bipartisan support for the Ohio Third Frontier, which he called the premier public-private innovation platform in the state and a model that has been replicated by many other states. He reiterated the good news mentioned earlier by Dr. Proenza—that the program was significantly extended shortly before the symposium by “a successful bipartisan effort to secure another $700 million for an additional five years of support. I think the real headline of the story is that in the face of a crippling recession and a time of government distrust, Ohio voters overwhelming approved the Third Frontier bond renewal measure by 62 to 38. The voters acted on their belief that Ohio needs to continue to invest in building its innovation economy.”

Mr. Stoff said that the Third Frontier results have been “impressive.” An independent analysis sponsored by the Roundtable and performed under the direction of the CFO of Cleveland-based Eaton Corporation, found that the investments produced a leverage ratio of 8.5 to 1, , generating some $6 billion in venture funding from venture capital, the private sector, and the Federal government. It reported a return on investment of 22 percent per year, and creation of 68,000 jobs with average salaries of $65,000. Some 650 companies had been created, capitalized, or attracted. “We’ve now set the bar even higher,” he said, “as the Third Frontier enters its next phase.”

Mr. Stoff concluded by noting that this encouraging news was to some degree offset by significant challenges, which would be described by panel members at the symposium. “But that tension is stimulating and thought provoking,” he said, introducing the first speaker and the topic of relative state performance across the country.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE OHIO INNOVATION ECONOMY

Mr. DeVol, then executive director of economic research at the Milken Institute, said he would describe recent findings of Milken’s State Technology and Science Index (STSI), which annually compares technology innovation activities in all 50 states. 1 He said that according to the index, begun in 2002, innovation is becoming steadily more important in determining state and regional economic success.

He said that many of the factors that determine national economic performance also affect regional growth. The regions, however, do not face the same

![]()

1Ross C. DeVol, Kevin Klowden, and Benjamin Yeo, “State Technology and Science Index 2010,” Miliken Institute, January 2011. Access at <http://www.milkeninstitute.org/pdf/STSI_exec.pdf>.

constraints as the national economy. An example is that labor is much more mobile between regions than between countries, with individuals able to move more quickly toward job opportunities. In addition, regional migration trends can affect growth for long periods. Any explanation of regional growth patterns, he said, must recognize these factors.

There are also barriers to the flow of economic activity across state borders. Regions actively compete for new and expanding businesses, and depend on the growth of industries that produce “exports”—goods and services sold beyond their borders. The manufacturing sector is one of the most export-intensive activities, he said, and the output of manufacturing circulates and multiplies within a regional economy to create a large “ripple effect.” Healthcare services is also an export sector in some regions, including northeast Ohio. This sector both attracts patients from throughout the Midwest, based on the reputation of the Cleveland Clinic and other facilities, and acts as a magnet in attracting firms engaged in biotech, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices. Such firms commonly act as engines of economic growth.

Many factors create disparities in growth among regions, he said, factors which interact in complex and dynamic ways. “The existing industrial structure can determine growth for a number of years. Each region inherits its industrial structure from historically determined factors, especially the costs of doing business, including tax rates, capital costs, wage rates, real estate prices, energy costs, and health care costs.” Increasingly important, he said, are “labor force skills, access to markets, access to capital, research and development, innovation capacity, and “quality of place” issues.” In the future, he predicted, new factors are likely to emerge.

A Review of the Milken S&T Index

The most recent index had been released a few months earlier, using five composite categories with a total of 77 individual components. For example, the research and development composite had 18 components, beginning with Federal R&D, Industry R&D, and Academic R&D. The 50 states were ranked in “tiers” of 10 by colors on a map of the U.S. Those in the top tier were portrayed in green, the second tier in yellow, the third in orange, and the fourth in red. He said that many of the region’s leading the R&D category were clustered together by region “because knowledge is generated, transmitted, and shared more efficiently in close geographic proximity.”

“To build a new industry cluster, the research and innovation capacities of a region are critical,” Mr. DeVol said. “You can start a new cluster by importing firms that have commercialized technology elsewhere, but those regions that have the basic research and development activities have an advantage in building a cluster than can hold together over the long term.”

The R&D composite, he said, measured type of R&D funding as well as how funds are spent. Also, everything was calculated on a per capita basis. He noted substantial strength in the Northeast, New England, the Mid-Atlantic

states, and in the West. The good news for Ohio, he said, is that it had moved up to the 20th position in the 2010 index in the R&D component from 28th two years ago, and from the third tier to the second tier.

In the R&D composite, Mr. DeVol noted “pockets of strength,” but found the low “NSF funding”—in which Ohio ranked 44th—“troubling,” because it suggests “less than a full-strength innovation pipeline.” Ohio had seen a noticeable improvement in Academic R&D, rising from 30th to 21st place, and had moved up five places in Industry R&D to 19th. Some strengths in the state included R&D Expenditures on Engineering, where it ranked 10th, and Biomedical Sciences, where it ranked 14th and Life Sciences, ranking 19th. Improvement in STTRs and SBIRs was notable, both rising from the 2007 and 2008 positions.

“So Ohio is in the upper tier of most indicators,” he said, “including the very good news that Ohio was in the top 10 in Phase I and II SBIRs. So there is some evidence of improvement in the R&D pipeline.” He called its ranking of 9th and 10th in Phase I and II SBIRs “a dramatic improvement” from eight years ago, when the index was first released.

Improvement in Access to Capital

Turning to the composite for risk capital and entrepreneurial infrastructure, Mr. DeVol said that “if you want to be successful over the long term, a state needs capable entrepreneurs and the risk capital that fuels growth and allows them to convert research to commercially viable technology products and services. We think this [composite] does a fairly accurate job of capturing that.” He added that a new conceptual framework recognizes the role of entrepreneurship in determining the economic growth of states and regions. The index included entrepreneurial activities influenced by training and support from both private and public sectors and availability of early stage financing. “But we really need to measure the intensity of the entrepreneurial activity through the extent to which individuals recognize opportunities and have the skills to exploit them. This determines the number of new startups, how many grow to be successful firms, and ultimately the jobs that are created.” He noted that Ohio has moved up rapidly to 20th from 40th two years ago in this indicator, indicating “significant improvement in entrepreneurial activities in the state of Ohio.”

Mr. DeVol added that the index uses the term “access to risk capital” to refer to “the smart money,” to angel investors and venture capitalists whose connections are part of dynamic ecosystems with links to management talent where it is needed. “So it’s about the skills, the connections they help establish in an area.” Ohio had improved quickly in the availability of venture capital, moving to 11th position. It had also risen sharply in the number of companies receiving VC investments, moving from 39th to 11th. He added that of all the indicators he reviewed for the index, the most encouraging was the jump in business startup rates to 15th on a per capita basis, up from 49th two years ago.

“This was a tremendous increase in early-stage startups,” he said. “And the state also scored very high in VC investments in clean technology.”

Less Progress in Human Capital

In the composite for investment in human capital, however, he found less progress. Mr. DeVol said that concentrations of talent today are more important than “industry agglomerations” in attracting firms to states. “They both matter,” he said, “but the key is really the ability to attract talent.” Among the indicators he described were “stock,” the percentage of a population with a bachelor’s degree or above, and “flow,” recent graduation rates in STEM fields. U.S. states cannot compete on a low-cost, low skill basis, he said; they must compete on the ability to generate ideas in the global marketplace and, more importantly, in the new products and markets that accompany productivity growth. “You have to understand the importance of harnessing the knowledge that’s generated locally and importing it where necessary to be successful in the long term to fuel economic growth,” he said. Ohio ranked just 35th in the 20 indicators in the Human Capital Investment Composite. Generally, Ohio’s best rank was 17th in the stock measures for Students in Science, Engineering, and Health as a percentage of the adult population. The ranking of 37th in the number of Bachelor’s Degrees Per Capita “is not an encouraging sign.” Another unfavorable statistic is State Appropriations for Higher Education, where Ohio ranks 40th.

Mr. DeVol saw some strength in the number of Doctoral Science and Engineering Degrees Awarded and the number of Doctoral Engineers, at 19th and 22nd. “But when you look across the indicators, Ohio is typically in the middle tier of most of these human capital measures.”

Attracting Talent

Mr. DeVol turned to the Technology and Science Workforce, which he called “a little different” because it describes the ability to attract talent from other places in terms of “intensity.” “Regions with a high concentration of skilled technology and science workers,” he said, “have the advantage of being able to pool intellectual capital with labor force skills specific to those sectors. As design engineers, programmers, and microbiologists migrate from one region to another, they reinforce the initial advantages of a region and bring new comparative advantages from people outside the region.” This is because young people who are highly mobile and geographically discriminating are “the most important labor assets a state can have.” At 23rd, Ohio scored a little better in this category, he said. The 18 occupational categories were divided into computing, information sciences, and life sciences. The states that have aboveaverage scores in these categories, he said, are typically highly dependent on technology and high-value-added industries. Massachusetts has been number one on the index since it was created, while Ohio is in the middle of the pack in

most of these indicators. Its best score is for Biochemists and Biophysicists, at 9th, and Database and Network Administrators, at 13th. He also reported “fairly strong rankings for Physicists and for ‘Other Life Sciences,’ both at 7th,” and for the catchall category Other Engineers, at 9th. “These are the occupational categories that are critical for Ohio moving forward,” he said.

The last major category is the Technology Concentration and Dynamism composite, which measures technology “as it is deployed on the ground.” Indicators include payroll, employment, and net business formation, “all pointing to the success of a region as its tries to move forward.” Mr. DeVol called this “more of a measure of technology outcomes, as opposed to the innovation pipeline as it flows through.” Most states that score well here, he said, have a diverse technology background and composition of industry clusters. Entrepreneurism plays a large role here, too, “because it’s about new companies being started in the technology and science areas, and about your ability to grow them.” Unfortunately, Ohio scored 44th in this category. He said that part of the reason for the low score was that part of the data came from 2008, the depths of the great recession, which hit Ohio harder than many other states. But even adjusting for this, he said, did not do much for Ohio’s scores, which were typically 30th or 31st. The best score was in the Number of Inc. 500 Companies per 10,000 Establishments, where Ohio was 19th.

‘A Definite Improvement’ for Ohio

Putting together the five composites and their 77 indicators, Mr. DeVol said, gave Ohio a rank of 29th, which he called “a definite improvement from where it was a few years ago.” At the top of the list, Massachusetts was number one, Maryland had moved to second place, Colorado had moved ahead of California on a per capita basis to third place, California scored fourth, and Utah had risen rapidly to fifth, “now nipping at California’s heels.”

Despite Ohio’s position of 29th, he said, the state tied for the biggest increase from the previous index, having moved up seven places. This was propelled by significant improvement in the risk capital infrastructure and business startup rates. “So you’re starting to see from many of the early indicators that Ohio’s moving in the right direction. But it must continue to improve on many of these, especially in human capital area and success in commercialization.”

One of the clearest barometers of a state’s economic standing, Mr. DeVol said, is the per capita income of the working age population. About three-fourths of the variation in per capita income can be explained by how well the states score on the 77 indicators of the State Technological and Science Index. “But we think the most dominant of these explanatory variables are the human capital measures, including the talent and the entrepreneurial indicators, which are growing increasingly important.”

DISCUSSION

Mr. Stoff asked what it would take for Ohio, at best a second-tier state, to move into the first tier. Mr. DeVol said that he had argued for years that universities are the most important assets of an innovation economy. Among high-tech clusters, those most successful in building a regional economy have universities that recognize that role. Whether they are effective is most often determined by the leadership of the president or chancellor. “I would argue that the most important thing any region can do is see that universities, especially public universities, do have a role to play. Many times that just means being willing to work with industry, allowing them to have access to some of the top research, or arranging a formal licensing arrangement.”

Such relationships are essential for attracting new firms, he added. “When you look around the country, a key factor that firms look at is whether the universities are engaged with the private sector. Do they have the research capacity, the will, and the support to allow scientists to interact with the private sector?” He said that while an active university is necessary, it is not sufficient. “You also need incentives to encourage entrepreneurism—not only in the universities but also in the private sector. I would say a key challenge for Ohio and other states in the Midwest is the historical assumption among those entering the labor market that you’re going to work for someone else, typically a medium or large company, and that entrepreneurship is not an option for you. This cannot be changed overnight, but it must be part of a relearning process.”

Dr. Wessner commented that other states are making substantial investments to enhance the innovation potential of their universities. He said that Texas is investing in two new research universities, partly to reduce the outflow of top graduate students. “They also recognize that if you have research universities, you have the potential to receive substantial R&D funding from the Federal government.” He also asked about the increase in VC activity detected by the Milken index, asked whether it represented a trend or merely the impact of a few large deals. Mr. DeVol said that the index included not just the total VC dollars but also the number of deals, but that it was too early to tell whether the rise represented a trend. While VC investments in Ohio were encouraging, he said, it was essential to “follow through to make sure startup companies that have been funded actually grow to become medium-sized firms that create jobs.”

MEETING THE GLOBAL INNOVATION IMPERATIVE

Charles Wessner

The National Academies

On behalf of the National Academies, Dr. Wessner expressed his thanks to the co-organizers of the symposium, and expressed his admiration for the region in generating so many agile innovation based development

organizations that encourage cooperation among sectors. He said he was also encouraged by the portions of Mr. DeVol’s report that indicate a firmer and more collaborative base for innovation in northeast Ohio. “When a community begins to understand that they can, or have to, do things differently, that is the point when bringing in best practices from around the world can be most helpful.”

Dr. Wessner said that the key to economic development for regions as well as for nations in the future is a well-functioning innovation ecosystem, and offered the following definition: Innovation means transforming ideas into new products, services, or improvements in organization or process. What this means, he added, is that “innovation translates knowledge into economic growth and social well-being.” He said that while many academics and policy makers “could debate with you for hours about the correct definition of innovation,” he found an informal description to be useful: “Research converts dollars into knowledge, and innovation converts knowledge back into many more dollars.”

“It’s a virtuous cycle,” he said. “Why is there an imperative to innovate? Because we have no alternative; if we want to grow our economy, maintain our place in the world, provide a future for our children and grandchildren, it is imperative that we innovate.”

‘Innovation Policy is Not a Hobby’

Adding urgency to the debate in the United States, he said, is the fact that countries around the world are working hard on their own innovation strategies. “Innovation policy is not a hobby,” he said. “It is not something you do when you have done everything else on your day-to-day policy agenda. It is the main game, the job of government at macro and micro levels. You need to support funding for research, and you need to convert that research to something we can use—not just another publication.”

Virtually all U.S. trading partners, Dr. Wessner said, have placed innovation high on their list of national priorities. Leading countries and regions are providing a high-level focus on growth and strength, sustained support for universities, consistent funding for research, imaginative support for small businesses, and support for government-industry partnerships that bring new products and services to market. “They’re committed, they’re focused, and they’re willing to spend.”

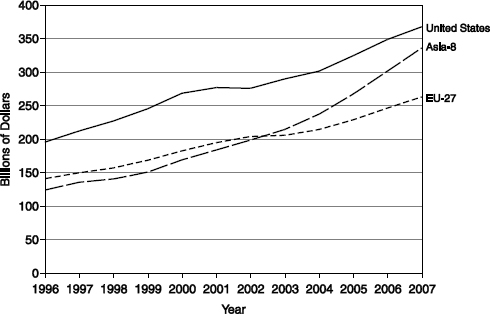

The rapidly growing R&D expenditures of the Asia-8 economies (China, India, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand) surpassed those of the EU-27 in 2003.

SOURCE: National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2010, Arlington, VA:

National Science Foundation, 2010.

FIGURE 1 Asia’s surge: Global R&D—Measuring commitment to innovation.

SOURCE: Charles Wessner, Presentation at the April 25-26, 2011, National Academies Symposium on “Building the Ohio Innovation Economy.”

Dr. Wessner singled out the case of China, which is doubling its R&D investments, building out R&D infrastructure and facilities, creating world-class universities, and investing in education at all levels to enhance its economy and national security. He cited President Hu Jintao’s Report to the 17th National Congress of the Community Party of China: “Innovation is the core of our national development strategy and a crucial link in enhancing the overall national strength.” He also cited Mu Rongpin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who wrote in the 2010 UNESCO Science Report that China’s goal is to become an “innovation-driven economy” by 2020.

The payoff of this commitment in China and in Asia more broadly can already be seen, he said, pointing out that the rapidly growing R&D expenditures of the Asia-8 economies (China, India, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand) surpassed those of the EU-27 in 2003 and were poised to overtake those of the U.S.2 “If these trends continue,” he asked,

![]()

2National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2010, Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, 2010.

“how can we be ahead of the rest of the world? How can we even stay where we are if we don’t make these investments in research and development?”

The Fallacy of the Low-wage Argument

Dr. Wessner also added that the U.S. can no longer use the excuse that it can’t compete with China because of its low wage structure. “Germany is a high-wage, highly-regulated economy,” he said, “with high welfare costs and government health insurance programs. But German companies do well in sending products abroad because they understand that technological capacity matters. They know that this is what produces jobs and trade surpluses.” He added that the Germans understand the importance of the manufacturing sector, and have created the institutional structure necessary to maintain it, including investments in job training and worker retention; support for raising productivity to offset high wages; assistance to small manufacturers in global marketing; and energy and transportation policies that have fostered an edge in manufacturing. This structure includes the Fraunhofer Gesellschaft—a network of 59 institutes, 17,000 employees, and a budget of about 1.6 billion euro—that conducts focused, product-based research in partnership with private firms. Dr. Wessner noted that this focus on advanced manufacturing and exports is paying off for Germany: “Germany has learned to send products to China and cooperate with the Chinese on standards. It has now almost balanced its trading account with that country.” German exports have jumped 17 percent this year, driven in large part by a 55 percent rise in exports to China.

The major risk for the U.S., Dr. Wessner suggested, is complacency—a belief that the U.S. can expect economic leadership without working very hard for it. “One of the myths we have,” he said, “is that U.S. workers can outcompete anyone in the world on a level playing field. There are two problems with this myth. First, the whole world works hard to make sure we’re never on a level playing field.” Second, he said, studies by the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) show that U.S. workers are less well educated than those of U.S. trading partners. In addition, Americans are increasingly spending more on current consumption rather than on investments in R&D as previous generations did and as other nations do. Since the late 1950s, federal spending on research and development as a percentage of GDP has been declining.3

The Power of Public-sector Investment

While, some argue that private investment in R&D is more than makes up for the decline in Federal investment, Dr. Wessner said that this private investment is limited largely to market-stage applications rather than to basic

![]()

3KPCE; National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2008, Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, 2008.

research. In many cases, privately funded R&D builds on technology platforms developed through substantial federal investments. He cited a comment by a leading venture capitalist, Mary Meeker of Kleiner Perkins, who noted: “Private investment may have given us Facebook and Garmin, but public sector investment gave us the Internet and GPS.” He stated that government investment in technology, education, and infrastructure, which has been a strong tradition since the late 18th century,4 will be a key part of addressing the challenge of innovation.

Ohio, Dr. Wessner said, can learn from the diverse approaches taken by other states to grow their innovation economies. New York, for example, has started a major nanotechnology initiative—despite having limited previous semiconductor industry or nanotechnology expertise. The state drew in what it needed, finding major partners in IBM and other global-scale firms. It attracted SEMATECH, then located in Texas and secured funding from investors in Abu Dhabi. Funding from the New York state government, which committed $2 billion to the effort, helped build a new College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering. To date, the this effort has yielded more than $5 billion in privatefirm investments, and new jobs in manufacturing and other high-value fields. For example, one of America’s only green-field silicon wafer fabrication plants is being built near Albany by Global Foundries at a cost of $5.6 billion, providing 1,400 new jobs. Dr. Wessner said that the lessons from the New York initiative include: addressing emerging technological needs; concentrate resources; encouraging innovative management, allowing universities freedom from restrictive rules; and creating strong connections between universities and the private sector to identify needs and attract funding.

Turning to Ohio, Dr. Wessner suggested that the state does stand out in making a “remarkable multi-institutional effort, which in itself ought to be one of the Milken categories.” He also said that the state has invested well and has made substantial progress in growing more than 400 advanced energy companies. It has also promoted development of new clusters for flexible electronics, photovoltaic manufacturing, and polymer-based technologies. He encouraged the state to seek more partnerships in Washington, capitalizing on new federal commitments to innovation and the bipartisan support for the kinds of initiatives Ohio has already launched.

![]()

4In 1798, for example, Eli Whitney received a government grant to produce muskets with interchangeable parts, leading to the first machine tool industry. In 1842, Samuel Morse received a federal award to demonstrate the feasibility of the telegraph. In 1903, the Wright Brothers fulfilled the terms of a U.S. Army contract by demonstrating the first flying machine. More recently, many platforms of the modern economy, including radar, computers, jet aircraft, semiconductors, the Internet, nanotechnology, flexible electronics, and solar technologies, have been built on government-funded research and public-private partnerships.

The Financing Needs of Early-stage Firms

Dr. Wessner urged a greater focus on small businesses, which make multiple contributions to a region. They create jobs, new products, increase market competition, generate taxable wealth, create welfare-enhancing technologies, and, over time, transform the composition of the economy. Equally important, they have the potential to become the “new big businesses.” A key impediment to the growth of small innovative businesses, however, is the ‘Valley of Death,’ the popular term for the phase of development where firms do not yet have sufficient revenue to grow on their own but lack the revenues demanded by VC investors. “It’s hard to attract VC funding,” said Dr. Wessner, “because new ideas are new, and no one can know what they will ultimately be worth.” He recalled that the Larry Page and Sergy Brin of Google had difficulty raising early-stage funding because no one could foresee the value of their particular search engine. “It’s not always clear at first,” he said. “You need that capital to get across the valley and demonstrate value.”

Dr. Wessner recommended several government mechanisms designed to help small, early-stage firms, beginning with the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. “Not enough people in Ohio know about this $3 billion annual program. It is very competitive; only about 20 percent of companies are selected in the first round. But it provides you with an initial $150,000, which brings validation and opportunity to explore.” A key feature of SBIR is that it is a set-aside from existing research budgets, rather than a program with annual budget fluctuations. He suggested that other Federal programs, notably the Technology Innovation Program, and the Manufacturing Extension Program at the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), and the various initiatives of the Economic Development Administration (Department of Commerce), would all be useful in providing support for Ohio’s innovation strategy.

Dr. Wessner concluded with the suggestion that Ohio could best accelerate its drive for innovation through local leadership—especially support for infrastructure, matching R&D grants. For example, “Phase Zero” grants by the state can help small Ohio firms apply for federal SBIR funding. The state can also offer bridging money for firms that are making the transition from SBIR Phase I to Phase II. These and other initiatives are underway in a number of other states, he said, as a way to encourage new businesses and promote regional growth. Other states are also taking steps to ensure that taxes are applied intelligently, and that regulations are not “worse than the tax structure.” In short, Dr. Wessner concluded that the region and the state can do much more to make northeast Ohio attractive to companies and better prepared to compete globally.

“The question is,” Dr. Wessner said in summary, “will we make the necessary investments in research and universities, and will we help our small companies compete? Our companies are one of our principal assets. We need to preserve the ones we have, and we need to grow new ones. Quite literally, the

future of our children depends on what we do over the next decade. I congratulate you on the progress you’ve made so far.”

DISCUSSION

Mr. DeVol affirmed the danger of excessive complacency in the U.S. “One thing I find troubling when I talk to legislators and their staffs is the idea that we have a divine right to lead in innovation. That biomedical, pharmaceutical, biotech, and other firms are here because they deserve to be. That we don’t have to worry about whether they are innovative or what other countries are doing.” He asked, “How do we cut through the idea that we’ve always been number one, and therefore we always will be?”

Illustrating the point, Anna Barker, a former deputy director for strategic scientific initiatives at the National Cancer Institute, said that leadership in life sciences is now moving offshore. Responding to the enormous looming problem of lung cancer in China, a nation of some 300 million cigarette smokers, Chinese officials told her on an earlier visit to Beijing that they were planning a new genomic center to address this problem. When she went back a year later, she expected to see no more than plans for the center. Instead she found a completed institution with 2,400 people, including 1,000 in bioinformatics. “This is a field where we are faltering,” she said. “We haven’t trained our kids well in computational biology or computation in general. So on every front China is driving innovation in education, in the new areas of science, like nanotechnology. In the next 10 years we’re either going to have to partner with China to get some of that information back, and gain from what we have invested, or we’re going to fall very far behind. We still have a choice, but time is running out.”

Bob Schmidt, of Cleveland Medical Devices, said that while universities receive far more funding than the SBIR program, small firms produce far more patents, and asked whether the SBIR should not logically receive more money. Dr. Wessner agreed that small businesses are effective in developing patents and, above all, products, but that the “universities are where many of the ideas come from.” Furthermore, the distinction between universities and small business may be blurred when “a researcher has an idea in the lab, and then goes across the street to become a small business.” He suggested that it was appropriate to see both activities as part of the same system. He said that in a recent study of the SBIR program, the National Academies had found additional resources in the SBIR program would be effectively used, but also noted the need for expanded support for basic research, applied research, and especially translational research to move innovations toward the marketplace.5

![]()

5National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008.