In response to the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), the National Research Council appointed a committee operating under the auspices of the Naval Studies Board to study the issues surrounding capability surprise, both operational and technical, facing U.S. naval forces—the Navy, the Marine Corps, and the Coast Guard.1 Capability surprise is both inevitable and inherently complex. It has multiple dimensions, including time, mission, and cross-mission domains; anticipation of enabling technologies; physical phenomena; and new tactics that may enable surprise.2 Anticipating and mitigating capability surprise may seem daunting for U.S. naval forces in today’s evolving national security environment. However, many efforts are already under way that could be leveraged to bring about an increase in preparedness against surprise through focus, culture, and U.S. naval leadership.

DEFINING “SURPRISE” AND STUDY SCENARIOS

From a military operational context and for the purposes of this report, surprise is an event or capability that could affect the outcome of a mission or

_____________

1Throughout this report, the terms “Navy,” “Marine Corps,” and “Coast Guard” are used. Unless stated otherwise, these refer to the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Marine Corps, and the U.S. Coast Guard.

2Surprises may come over timescales ranging from seconds to minutes in a complex engagement, to the evolving, breakthrough surprise that might have been secretly developed over decades. The mission domains such as air defense and undersea warfare, which U.S. naval forces operate across the open ocean and littoral (land, air, space, and cyberspace), all have myriad entry points from which capability surprises can originate. There are also accelerating new technological advancements globally, which singularly or in combination can constitute the basis of a capability surprise.

campaign for which preparations are not in place. By definition, it is not possible to anticipate true surprise. It is only possible to minimize the number of possible surprises by appropriate planning, to create systems that are resilient to the unexpected actions of an adversary, and to rapidly and effectively respond when surprised. There are two classes of surprise that fall within this military operational context and conform to the terminology provided in the study’s terms of reference:3 (1) intelligence-inferred surprise and (2) disruptive technology and tactical surprise.

“Intelligence-inferred surprise” is an event or capability developed over a relatively long time line—years—that U.S. naval forces were aware of in advance of its looming operational introduction, but for which they might not have adequately prepared. “Disruptive technology” (including the disruptive application of existing technology) and “tactical surprise” are short-time-line—hours to months—events or capabilities for which naval forces probably have not had sufficient time to develop countermeasures. In some cases both types of surprise can occur—for example, a much anticipated surprise capability that is found on the battlefield to have tactical war reserve modes.

Two variants of disruptive technology and tactical surprise have been identified. The first is the pop-up of a new capability enabled by a new technology or an unexpected application of an existing well-known technology—for example, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) as well as unexpected tactics. The second variant, black swan events—may be “self-inflicted” surprises—for example, blind spots or vulnerabilities in our own systems. Here, no amount of surveillance would have allowed anyone to predict the event.4 Such events may also be the result of a sudden U.S. policy change or directed action, such as Operation Burnt Frost,5 or natural disasters that are to be anticipated but not on such an extreme scale—for example, the March 2011 Fukushima Disaster.6

Sometimes the mitigation of surprise will take the form of naval forces

_____________

3The study’s terms of reference (TOR) are provided in the Preface. The TOR charged the committee to produce two reports over a 15-month period. The present report, the committee’s final report, accords with the committee’s interim report and contains similar text; however, it provides specific findings and recommendations along with additional analysis.

4Nassim Taleb defines a black swan as “a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics: It is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable, than it was.” For additional reading on black swan events, see Nassim Nicholas Taleb, 2010, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, 2nd edition, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, N.Y.

5Operation Burnt Frost was the mission to shoot down a nonfunctioning National Reconnaissance Office Satellite in 2008. RADM Brad Hicks, USN, Program Director, Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense, “Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense: Press Briefing, March 19, 2008,” presented to the committee by RADM Joseph A. Horn, Jr., USN, Program Executive, Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense, and Conrad J. Grant, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, May 16, 2012, Washington, D.C.

6A partial profile of U.S. naval response to the Fukushima disaster—a combined earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear reactor catastrophe—in a coordinated effort known as Operation Tomodachi is found at http://www.nbr.org/research/activity.aspx?id=121. Accessed June 13, 2012.

developing their own surprises as potential counters. Throughout this report, when the committee refers to “mitigation,” the term includes not only measures to counter the potential surprises of an adversary but also our own surprises delivered preemptively.

As discussed at length throughout the report, the committee recognizes that surprise cannot be completely anticipated. One cannot, for example, anticipate precisely how even an intelligence-inferred surprise will unfold. Therefore the resilience of U.S. naval forces and their capabilities will remain key. Resilience takes a number of forms:

1. Design features in mission systems to counter or protect against such surprise vectors as electronic countermeasures and cyberattacks.

2. War reserves in the form of backup systems or frequency bands in case a primary system or channel is rendered inoperative.

3. Exercises to explore alternative tactics, techniques, and procedures for use if and when adversarial surprises are unleashed.

4. Training for warfighters and mission operators that incorporates surprise elements not only to develop resourcefulness in surprise mitigation but also to instill the confidence that surprises usually have work-arounds.

5. As part of our proficiency training, creation of our own countersurprises to give pause to an adversary’s tactics and buy time to counter its surprises.

6. Provision of design margins (such as power and space) on platforms to support rapid fielding capabilities as necessary.

7. Plan for low-cost countersurprise tactics that use nonkinetic effects such as deceptive electronic countermeasures, decoys, and cyber operations.

8. Development of contingency plans for deployment of special operations forces.

In accordance with the terms of reference and to guide its analysis and, ultimately, identify findings and propose recommendations to U.S. naval leadership, the committee selected three surprise scenarios:

• Scenario 1: Denial of space access;

• Scenario 2: An asymmetric engagement with complex use of cybermethods in a naval context; and

• Scenario 3: A black swan event to which the front-end scanning and prioritization framework for mitigating surprise is not applicable.

In short, these scenarios aided in studying what U.S. naval forces are doing and could do to anticipate and respond to capability surprise and to mitigate it. These scenarios were chosen in part because they address issues important to the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard. Denial of space access is treated

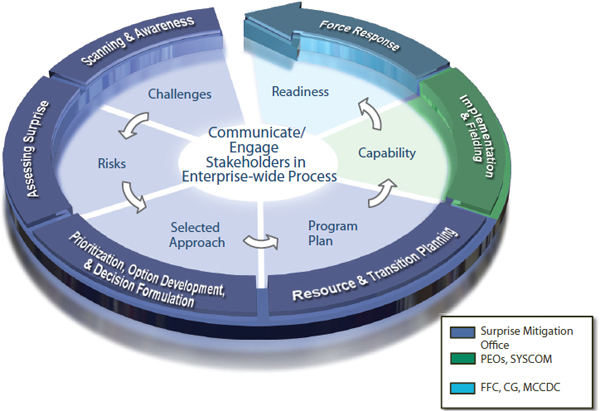

FIGURE S-1 Recommended framework for addressing capability surprise.

in a Navy context, social media manipulation is framed to suit a Marine Corps environment, and disaster relief would typically involve the Coast Guard.

A FRAMEWORK FOR ADDRESSING SURPRISE

With the above-mentioned scenarios in mind as well as exemplars for a military response, which will be introduced later, and to guide U.S. naval forces in addressing a potential capability surprise, the committee adapted a functional framework consisting of six phases that can be aligned with the development functions, accountabilities, and principles required for effective surprise mitigation.

The framework, shown in Figure S-1 and described in greater detail throughout this report, comprises six phases: (1) Scanning and Awareness; (2) Assessing Surprise; (3) Prioritization, Option Development, and Decision Formulation; (4) Resource and Transition Planning; (5) Implementation and Fielding; and (6) Force Response.

Options for Coordinating Surprise Mitigation

In order for leadership to enable U.S. naval forces to implement and manage surprise mitigation, virtually every development and acquisition program conducts some form of the following:

• Threat-response activities, including the projection of future threats,

• Development effort directed at meeting the projected threats, and

• Continual assessment of existing and developmental system designs for potential vulnerabilities so that corrective measures can be undertaken.

At the same time, a number of mission or mission-support capabilities are of primary concern:

• There is presently no authorized office to address these concerns,

• There are areas of vulnerability in programs for which no executive has been identified to coordinate the surprise mitigations,

• The potential impact on mission capabilities of surprises that pop up from emerging technologies or applications of existing technology is at present ambiguous, and

• There is no assurance that sufficient attention is paid to identified risks.

Finding 1: Capability surprise is both inevitable and inherently complex, and it requires U.S. naval forces to engage in a broad spectrum of issues, from horizon scanning to red teaming to experimentation and rapid prototyping, to exercising, fielding, and training. While there are a few exemplar organizations in the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard as well as the Department of Defense that effectively work on capability surprise, there is neither an overall framework for nor a clear delineation of U.S. naval forces responsibilities.7

Recommendation 1: The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), the Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC), and the Commandant of the Coast Guard (CCG) should establish a common framework for U.S. naval forces to address capability surprise, as shown in Figure S-1.

The CNO, in concert with the CMC and the CCG, should establish and fund a surprise mitigation office to serve as the executive agent for addressing capability surprise for U.S. naval forces. Specifically, this office should comprise a set of organic operational, technical, assessment, and intelligence-oriented staff and draw input and analysis with a global, multicultural perspective from a multitude of communities: operational; intelligence; acquisition, research, and development; system commands; program executive offices; war colleges; military fellows; government laboratories; Federally Funded Research and Development Centers; university-affiliated research centers; industry; and academia. To ensure that U.S. naval forces are proactive in developing and anticipating surprise capabilities it is recom-

_____________

7Some exemplars identified by the committee include the Navy’s SSBN Security program, the Air Vehicle Survivability Evaluation Program (Air Force Red Team), and the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense program (in response to Operation Burnt Frost).

mended that representatives from Special Operations Command (SOCOM) be an integral part of this office. Based on the CNO’s decision above on which option to pursue (see Table S-1), the office should support the timely transition of surprise capabilities to the appropriate organizations of primary responsibility and monitor the transition to, and effectiveness within, operational forces.

To meet the committee’s objective of accountable attention to surprise, especially for nonacquisition programs as outlined above, eight “office options” were considered (Table S-1). Each of these eight options is described in detail in Chapter 1.

After weighing the pros and cons of each of the eight office options, the committee identified the N9I office as the existing organization best equipped to coordinate consideration of surprise for U.S. naval forces and work in concert with joint forces and national assets. The N9I office currently ensures integration across programs, i.e., warfare systems. Although its main role is to oversee integrated financial and budget management, the N9I office also manages the Naval Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air (NIFC-CA) program. This program is particularly relevant because it requires the technical and operational integration of sea surface, land, and airborne combatants (Aegis, Army Aerostat, and E-2D) sharing information over networks—Link 16 and cooperative engagement capability (CEC)—to enable weapons such as the Standard Missile 6 to engage airborne cruise missiles over terrain that might be beyond the horizon of the firing unit, using composite track and targeting data. The ability of N9I to coordinate programs is essential for a capability surprise office dealing with surprises that are probably not addressed by a single new program or capability upgrade. To extend the N9I office’s mission to also mitigate capability surprise seems synergistic, but it will need additional staffing and coordination.

TABLE S-1 Office Options Considered for Surprise Mitigation for U.S. Naval Forces

|

|

||

| Option No. | Optiona | |

|

|

||

| 1 | Incorporate into existing N9I office | |

| 2 | Incorporate into existing N2/N6I office | |

| 3 | Establish new center of excellence | |

| 4 | Assign to Office of Naval Research | |

| 5 | Create rapid acquisition office with PEO | |

| 6 | Create new OPNAV office | |

| 7 | Delegate to OSD surprise office | |

| 8 | Incorporate into existing DASN (RDT&E) office | |

|

|

||

aOPNAV, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations; PEO, program executive office; OSD, Office of the Secretary of Defense; DASN (RDT&E), Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, Testing and Evaluation.

The committee was especially mindful that in the present era of limited resources and the need to consider affordability, a new office would be unrealistic. On the other hand, the committee was keenly aware it would be ineffective to simply declare the need for the framework and to advise the naval culture that it should embrace the consideration of potential surprises. As pointed out directly by the Defense Science Board, “Rarely is there a case of true surprise. Post mortems almost always identify that someone has provided warning, but that warning was not heeded.”8 Therefore, an office with sufficient authority and connectivity as defined by the recommended framework, is necessary to effectively address surprise.

The committee considered that it would be presumptuous to formally recommend option 1 if CNO determines, based on plans and considerations of which the committee is not aware, that another office is more appropriate. Therefore, the committee recommends the establishment of a surprise mitigation office and considers N9I the most likely organization to lead it for U.S. naval forces. It understands, however, that the CNO may identify a more appropriate entity to take on this role according to the framework presented and recommended in this report.

PRIORITY AREAS FOR ACTION:

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 2 THROUGH 6

The following five areas are key to successful surprise mitigation. Each is an integral part of the framework introduced earlier in this summary and discussed in detail in the report.9

Expand and Create Roles for Greater Scanning and Awareness

Finding 2: The Office of Naval Research-Global (ONR-G) is focused on scanning at the 6.1 and 6.2 levels; the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) on technical intelligence, primarily systems in development, testing, or operational exercises (6.3-6.7 levels); and fleet intelligence on observed operational behavior. However, there is no integrated, comprehensive scanning that also explores the linking of these observations and the emergence of consumer technologies of potential impact. While there are usually early indicators of potential capability surprises, there does not appear to be a coordinated means for U.S. naval forces to explicitly scan the horizon for such indicators; to capture, retain, and vet such indicators with relevant organiza-

_____________

8Defense Science Board. 2009. Report of the Defense Science Board 2008 Summer Study on Capability Surprise, Volume I: Main Report, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics, Washington, D.C., September, p. xiii.

9The findings and recommendations presented here are expanded on in Chapter 8 of this report, “Putting It All Together.” That chapter summarizes the essential elements of Chapters 2 through 7 and provides a context for the findings and recommendations presented here.

tions; and, ultimately, to inform senior leadership of potential capability surprises. Such a coordinated means would need to scan, recognize, categorize, analyze, and report technical and/or operational surprises on a global basis.

Recommendation 2: Using existing fleet resources, the Chief of Naval Operations should enlist the support of the combatant commanders and their naval component commands in order to scan, recognize, capture, and report potential capability surprises outside the continental United States (OCONUS). Most notably, the Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Europe and Africa, and the Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet, should establish comparable counterparts within their respective staffs to the surprise mitigation office referred to in Recommendation 1.

To further aid in identifying potential capability surprises—technological, operational, and/or otherwise—the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development and Acquisition (ASN RDA) should (1) appoint the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, Testing and Evaluation (DASN RDT&E) as the Navy Department’s Chief Technology Officer, with primary responsibility for providing technical advice for all phases of the framework for the surprise mitigation office in Recommendation 1 and (2) direct the Chief of Naval Research to establish a “virtual” scanning and awareness structure led by the Office of Naval Research-Global, engaging the technical, intelligence, and operational communities in order to systematically scan the horizon, maintain awareness, and conduct technology readiness assessments for both the CNO and the surprise mitigation office, as called for in Recommendation 1.

Improve Methodologies for Assessing Surprise

Finding 3: Organizations that anticipate and respond effectively to potential capability surprises—such as the Navy’s SSBN10 Security program, the Air Vehicle Survivability Evaluation program (Air Force red team), and the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense program (in response to Operation Burnt Frost)—appear to possess the following characteristics: senior leadership support; team independence; access to a strong base of cross-disciplinary technical and operational expertise; an ability to identify threats through campaign-level modeling, system-of-systems simulation, and high-fidelity physics-based models; precise vulnerability modeling and analysis capabilities validated by test and experiment data; mechanisms to recommend and/or deploy solutions as necessary; adequate, steady funding; and focus on a particular mission such as Navy SSBN Security. In addition, these organizations appear to leverage modeling, simulation, and analysis tools in conjunc-

_____________

10SSBN, nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine.

tion with a network of experts to expose bias, offer critical review, model and test against potential vulnerabilities, and demonstrate alternative solutions to respond to surprise.

At the same time, assessments of threats to the critical technologies that enable U.S. naval forces appear to be conducted on a small scale rather than being quantified, modeled, and characterized for U.S. naval forces as a whole. For example, threats to precision navigation and timing sources or cyberattacks embedded within Navy weapon systems could impact a wide array of naval operations. However, U.S. naval forces as a whole do not seem to be utilizing the best methodologies for assessing surprise. One of these methodologies would be the creation of red teams, that could simulate or represent adversarial thinking across global cultures.

Recommendation 3: As its first tasking from the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), the surprise mitigation office (see Recommendation 1) should (1) identify and prioritize any broad response to operational and technology threats that are not owned by any one mission authority and (2) establish threat study groups to characterize, quantify, and model these specific threats as well as leverage existing resources (modeling, simulation, and analysis tools and test data used by a network of subject matter experts in academia, industry, laboratories, and the Service colleges). The output from (1) and (2) should be disseminated to U.S. naval leadership as soon as possible. Careful attention should be paid to surprises not addressed by any program, or where a substantial gap exists between programs.

The CNO, the Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC), and the Commandant of the Coast Guard (CCG) should take steps to ensure that red teams—with sufficient independence and expertise but, at the same time, and a fresh influx of participants—are able to depart radically from traditional thinking in order to help U.S. naval forces as a whole prepare for combat and develop new tactics. In particular, efforts should be made to expand and periodically refresh the composition of red teams to achieve a greater diversity in thinking and better represent the adversary.

Work Joint and Naval Solutions for Responding to Surprise

Finding 4: With the recent establishment of the Strategic Capabilities Office within the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD AT&L), there appears to be an opportunity for a surprise mitigation office to provide naval force component solutions to surprises facing the entire Joint Force. Furthermore, there is an opportunity for both offices to draw on each other by sharing expertise, methodologies (modeling, simulation, analysis, red teaming), and learning.

Recommendation 4: The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD AT&L) should encourage their respective “surprise offices” to develop and foster a close working relationship with each other. In particular, the CNO and USD AT&L should direct their surprise offices to share ideas and to collaborate on methodologies (modeling, simulation, analysis, test data, and red teaming) in the interest of efficiency and obtaining consistent and coordinated results. Technical interchange meetings and the frequent exchange of information between the two offices and others that may be eventually established by the other Services should also be encouraged.

Plan for Surprise

Finding 5: In planning for surprise, deficits appear to have arisen in two areas:

a. Management processes by which resourcing decisions are made and that potentially impact preparations for capability surprise among U.S. naval forces appear to be inadequate and to lack reserve capacity. In particular, there appears to be limited flexibility in the way of design margins for platforms and payloads to respond to a range of potential capability surprises, and it further appears that the Department of the Navy’s investment in science and technology is insufficient to provide a robust array of technology building blocks that allow a rapid response to a broad range of potential surprises.

b. In addition, the Department of the Navy is not extending the full measure of open architecture principles throughout system development and deployment life cycles nor is it making best use of permissible contracting exceptions or best acquisition practices in responding to potential capability surprise in a timely and efficient manner.

Recommendation 5: In planning for surprise,

a. The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), the Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC), and the Commandant of the Coast Guard (CCG) should add to their respective program planning guidance an explicit provision(s) that allows them to resource unit considerations and equipment design specifications, such as adding some adequate design margins into platforms and payloads in response to potential capability surprise.

b. The Chief of Naval Research (CNR) should invest in discovery and invention (6.1 and early 6.2) research areas that take advantage of the entire payload value chain (i.e., payloads versus platforms; modularity versus integration; and reprogrammability), and inclusion of appropriate software and hardware design margins into development requirements. The Assistant

Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition (ASN RDA) should ensure that acquisition and contracting personnel are trained in the development of threshold versus objective requirements, the unique requirements associated with the use of commercial products, and the appropriate use of the waiver process in tailoring responses to potential capability surprise.

c. The surprise mitigation office (see Recommendation 1) should encourage broader cross-organizational pre-planning in anticipation of, and based on previous, black swan events that can cut across U.S. government department responsibilities, and it should also serve as the lead resource officer for the rapid fielding of new capabilities to counter unanticipated surprises.

Prepare for Surprise Now

Finding 6: In preparing for surprise, it appears that

a. U.S. naval forces are not preparing adequately for potential capability surprise in current exercises and experiments. For example, naval exercises do not usually accommodate degraded environments or unexpected developments to be realistically addressed, and training tends to focus on current operations and leaves inadequate time for experimentation and use of new technologies.

b. U.S. naval forces do not have an advocate and resource sponsor to rapidly field new capabilities to counter pop-up surprises, nor are they taking advantage of any existing capabilities, as identified in the Navy Readiness Reporting Enterprise (NRRE), that could potentially counter surprises of all types.

c. It is unclear whether some key classified capabilities—to the extent any exist—are disclosed to planners or operators and therefore may not be routinely incorporated into combatant plans or practiced by operators.

Recommendation 6: In preparing for surprise,

a. Operational commanders should incorporate, when feasible, degraded environments and aspects of surprise into exercise and training scenarios to improve preparation for and response to surprise. U.S. Fleet Forces Command (FFC), including directed type commanders, Marine Corps Combat Development Command (MCCDC), and U.S. Coast Guard Force Readiness Command (FORCECOM), should expand experimentation and related activities to create concepts and tactics to counter surprise. To offset resource impacts, activities of limited scope, such as small-unit or small-scale experiments, may be utilized.

These commanders should use the results from exercises and experimentation to analyze and assess their preparedness for capability surprise. As appropriate, they should formulate measures and incorporate them into the existing readiness reporting structures through the appropriate naval organizations and readiness reporting systems.

The results of incorporating surprise into exercises and experimentation will be forwarded to the appropriate Service organizations, including the capability surprise office, and entered into the training continuum, as appropriate.

b. Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces Command (FFC), should leverage the Navy Readiness Reporting Enterprise (NRRE) and provide operational commanders with any existing capabilities that could counter surprises of all types.

c. Finally, operational commanders should work to ensure that any of our key classified capabilities—to the extent any exist—are disclosed to planners or operators so that they are incorporated into combatant plans or practiced by operators in responding to capability surprise.

ROLES AND ACTIVITIES TO ADDRESS CAPABILITY SURPRISE

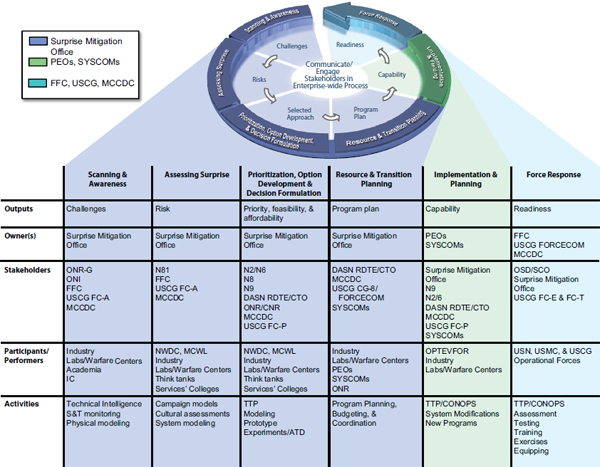

Figure S-2 summarizes the outputs; owners, stakeholders, and participants/performers; and activities in each phase of the framework. It is a compilation of the narratives in the chapters that follow. The stakeholders and participants are brought together, as appropriate, to assess signs of emerging surprises detected by the scanning and awareness activities of the operational, research, and intelligence establishments in Phase 1 and to move toward the modeling and assessment organizations and laboratories to verify feasibility in the middle phases. Finally, the acquisition and operational organizations are the primary players in the final phases. The activities of each phase are summarized, and the primary output of each phase is shown in the first row of the table, from identification of challenges to delivery of capability and ensuring of deployed readiness. Sometimes with disruptive surprises recognized only in the heat of an operation, a crash program will be initiated that involves only phases 4, 5, and 6, because the early observations have been preempted by new findings on the battlefield or disaster area.

The committee has determined that many or most of the requisite functions already reside within the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard. However, they are not sufficiently integrated, prioritized, or advocated. This determination is the primary motivation for Recommendation 1—namely, that a surprise mitigation office be established to coordinate and prioritize surprise mitigation for U.S. naval forces. The office would serve as the executive agent for the first four phases. The final two phases of the framework would be ably led by the identified existing organizations once the surprise mitigation office has prioritized, defined, and planned appropriate measures for its participation in these final phases to

FIGURE S-2 Roles and activities to address capability surprise. SYSCOM, Systems Command; IC, intelligence community; NWDC, Navy Warfare Development Command. See Appendix D for the definitions of acronyms that have not yet been spelled out.

ensure that the surprise mitigation capabilities are deployed in a suitable and timely manner.

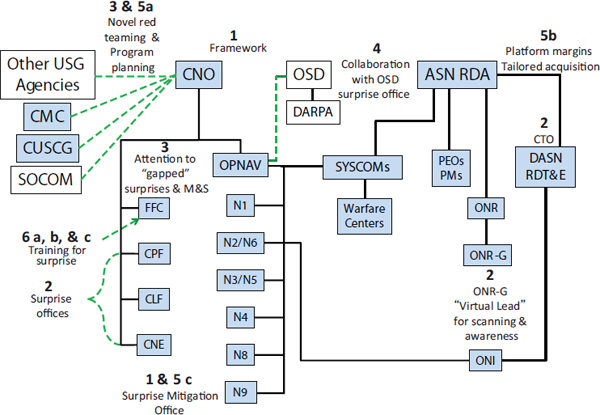

Figure S-3 maps the recommendations to organizations within and outside the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard. As shown from the mapping, the impact of each recommended change on any part of the organization is rather small; however, in the committee’s view, the sum of each of these changes would result in a much more integrated and prioritized approach to addressing capability surprise for U.S. naval forces.

In summary, the framework and organizational recommendations will enhance the ability of U.S. naval forces to prepare for capability surprise. The recommendations will further support the U.S. naval leadership and enhance the Navy’s culture of awareness and its proactive focus on becoming more resilient against surprise.

The report concludes with a ready reference describing how the recommendations would be implemented across the enterprise based on the details in the chapters.

FIGURE S-3 Mapping of recommendations to organizations within and outside the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard. Many of the acronyms have already been identified in the text. See Appendix D for the definitions of those that have not so far been spelled out.