This chapter presents the approach that the committee used to identify and evaluate the literature on health effects of blast exposure. It provides information on how the committee conducted its search of the literature, the types of evidence reviewed, the committee’s evaluation guidelines, the limitations of the studies reviewed, and the categories of association that the committee used in drawing conclusions about associations between blast exposure and long-term health effects.

SEARCH STRATEGY AND IDENTIFICATION OF LITERATURE

To identify the relevant published evidence on health effects of blast exposure, the committee began its work by overseeing extensive searches of the medical and scientific literature, such as published peer-reviewed articles and technical reports. Citation databases searched included MEDLINE, Embase, and the National Technical Information Service. Initial searches identified potentially relevant studies of blast-associated injuries other than traumatic brain injury (TBI) through March 2012. Additional searches for material on TBI due to blast exposure were conducted to retrieve studies from 2007 through June 2012 to capture studies that were not included in the previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Gulf War and Health, Volume 7: Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury (IOM, 2009). A final search was conducted in March 2013 to identify studies published since the previous searches. The various searches retrieved more than 12,800 potentially useful studies. A manual search of titles and abstracts was conducted to exclude nonrelevant studies. The titles and abstracts of

the remaining roughly 1,800 studies were then reviewed again. Scientific reviews and other review articles were manually searched for additional relevant studies. Numerous articles in languages other than English were included in the review and translated as needed. The committee also considered other sources of information, such as non-peer-reviewed reports and meeting summaries from the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

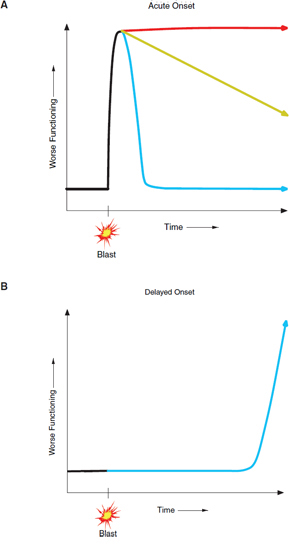

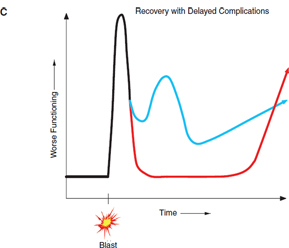

The committee focused its attention on clinical and epidemiologic studies of adults who may have long-term health effects (effects present at least 6 months after exposure) that resulted from a blast exposure. However, studies of immediate effects of blast exposures also were considered because acute effects (effects present immediately after the exposure to a blast that might last for hours to weeks) and subacute effects (effects that occur after acute and before long-term, present for weeks to 6 months) potentially could lead to long-term health effects (see Figure 2-1). Reviewing literature on acute and subacute effects of exposures to blast helped the committee to identify data gaps in the evidence base on long-term health effects.

Review of the roughly 1,800 titles and abstracts led to the identification of about 400 studies for further examination at the full-text level. To determine which studies would be included in the evaluation, the committee developed a set of inclusion guidelines (see page 25). All studies were objectively evaluated without preconceptions about health outcomes or about the existence or absence of associations.

The committee relied primarily on clinical and epidemiologic studies to draw its conclusions about the strength of evidence of associations between blast exposures and long-term health effects. However, animal studies played a critical role in clarifying the mechanism of blast injuries and provided biologic understanding of many of the effects seen in humans.

Epidemiologic Studies

Analytic epidemiologic studies examine associations between two or more variables. Predictor variable and independent variable are terms for an exposure to an agent of interest in a human population. Outcome variable and dependent variable are terms for a health event seen in that population. Outcomes can also include a number of nonhealth results, such as use of services, social changes, and employment changes. A principal objective of epidemiology is to understand whether exposure to a specific agent is associated with disease occurrence or other health outcomes. That is most straightforwardly accomplished in experimental studies in which

the investigator controls the exposure and the association between exposure and outcome can be measured directly. In the case of blast exposure studies, however, human experiments that directly examine the association between blast exposure and health outcomes are neither ethically nor practically feasible; instead, the association has to be measured in observational studies, and causality has to be inferred. Although they are commonly used synonymously by the general public, the terms association and causation have distinct meanings (Alpert and Goldberg, 2007).

There are several possible reasons for associations in observational studies: random error (chance); systematic error (bias); confounding; effect–cause relationships; and cause–effect relationships. A spurious association—the finding of an association that does not exist—can be due to random error or chance, systematic error or bias, or a combination of them. Random error or chance is a statistical variation in a measurement taken from a sample of a population that can lead to the appearance of an association when none is present or to the failure to find an association when one is present. Systematic error or bias is the result of errors in how a study was designed or conducted. Systematic error can cause an observed value to deviate from its true value and can falsely strengthen or weaken an association or generate a spurious association. Selection bias occurs when there has been systematic error in recruiting a study population, which is different from the target population of the study, with the result that the findings cannot be generalized to the target population. Information bias results from a flaw in how data on exposure or outcome factors are collected.

Other reasons for finding associations that are incorrect are confounding and effect–cause relationships. Confounding occurs when a third variable—termed a confounding variable (or confounder)—is associated with both the exposure and the outcome and leads to the mistaken conclusion that the exposure is associated with the outcome. Effect–cause relationships occur when the outcome precedes the exposure; for example, a study might suggest that a particular health outcome was associated with blast exposure when the health condition actually preceded the exposure. In a true association, the exposure precedes the outcome and the association is free of random error, bias, and confounding (or the chance of them has been minimized); finding true associations is the goal of epidemiologic studies.

Detection of associations can be affected by the prevalence of health problems in a given population. Attributing an incremental burden of a disease that is common in a population to a specific exposure can be difficult. However, a small increase in the number of cases of a rare disease in a population can produce an effect that is more apparently attributed to an exposure.

In epidemiologic studies, the strength of an association between exposure and outcome is generally estimated by using prevalence ratios, relative

risks (RRs), odds ratios (ORs), correlation coefficients, or hazard ratios, depending on the type of epidemiologic study performed. To conclude that an association exists, it is necessary for the exposure to be followed by the outcome more (or less in the case of a protective exposure) frequently than it would be expected to by chance alone. The strength of an association is typically expressed as a ratio of the frequency of an outcome in a group of participants who have a particular exposure to the frequency in a group that does not have the exposure. A ratio greater than 1.0 indicates that the outcome variable has occurred more frequently in the exposed group, and a ratio less than 1.0 indicates that it has occurred less frequently. Ratios are typically reported with confidence intervals to assess random error. If a confidence interval (95% CI) for a ratio measure (such as an RR or an OR) includes 1.0, an association is said to be not statistically significant; if the interval does not include 1.0, the association is said to be statistically significant.

Animal Studies

Studies of laboratory animals are essential for understanding mechanisms of action and biologic plausibility and for providing information about possible health effects when experimental research in humans is not ethically or practically possible (NRC, 1991). Such studies permit an injury caused by a blast to be introduced under conditions controlled by the researcher. Mechanism-of-action (mechanistic) studies encompass a variety of laboratory approaches with whole animals and in vitro systems that use tissues or cells from humans or animals.

In deciding on associations between blast exposure and human long-term health effects, the committee used evidence only from human studies; in some cases, however, it examined animal studies as a basis of judgments about biologic mechanism or plausibility.

Determining whether a given statistical association rises to the level of causation requires inference (Hill, 1965); that is, causality is inferred, rather than measured directly, in observational studies. In 1965, Austin Bradford Hill, a British statistician, suggested nine criteria that could be used to assess whether an association observed in an observational study might be causal:

- Strength of association. A strong association is more likely than a modest association to have a causal component.

- Consistency. An association that is observed consistently in different studies is more likely to be causal than one that is not.

- Specificity. A factor (or predictor variable) influences specifically a particular outcome or population.

- Temporality. A factor must precede an outcome that it is supposed to affect.

- Biologic gradient (also called dose–response relationship). An outcome increases monotonically with increasing dose of exposure or according to a function predicted by a substantive theory.

- Plausibility. An observed association can be plausibly explained by substantive (for example, biologic) explanations.

- Coherence. A causal conclusion should not fundamentally contradict present substantive knowledge.

- Experiment. Causation is more likely if evidence comes from randomized experiments.

- Analogy. An effect has already been shown for analogous exposures and outcomes.

Not all those criteria are applicable in all cases. For example, as noted above, randomized experiments that expose humans to blast would be not conducted. A strong association as measured by a high (or low) risk or ratio, an association that is found in a number of studies, an increased risk of disease with increasing exposure or a decline in risk after cessation of exposure, and a finding of the same outcome after analogous exposures all strengthen the likelihood that an association seen in epidemiologic studies is causal. Exposures are rarely, if ever, controlled in observational studies, and there can be substantial uncertainty in the assessment of a blast exposure. To assess whether explanations other than causality (such as chance, bias, or confounding) are responsible for an observed association, one must bring together evidence from different studies and apply well-established criteria (Evans, 1976; Hill, 1965; Susser, 1973, 1977, 1988, 1991; Wegman et al., 1997).

After obtaining the roughly 400 full-text articles, the committee needed to determine which studies to include in its evaluation. To do that, the committee developed inclusion guidelines. Box 2-1 includes examples of types of evidence used to categorize a study as primary or supportive (secondary or tertiary). Primary studies had greater methodologic rigor and therefore provided the strongest evidence on long-term health outcomes of blast exposure. For many health outcomes no primary studies were identified; in these cases, supportive studies necessarily guided the committee’s determi-

BOX 2-1

Inclusion Guidelines

Primary

- Cohort study

- Prospective study

- Objective data related to exposure

- Appropriate control or comparison group

- Minimal selection bias

- Long-term followup (more than 6 months)

- Objective outcome of assessment

- Sound analytic methods, sufficiently powered

- Peer-reviewed in some way

Secondary

- Case-control study

- Studies dependent on self-report of exposure or outcome

- Peer-reviewed in some way

Tertiary

- Case series or reports

- Peer-reviewed in some way

nations. If a study did not meet any of the guidelines, it was excluded from further examination.

A study had to have been published in a peer-reviewed journal or other publication–such as a government report, dissertation, or monograph–and had to include sufficient methodologic details to allow the committee to judge whether it met inclusion guidelines. A primary study had to include an unexposed control or comparison group, had to have sufficient statistical power to detect effects, had to use reasonable methods to control for confounders, and had to report followup data for at least 6 months. A study had to include information that the exposure was to blast. Ideally, there was an independent assessment of the exposure rather than self-reported information. Pre-exposure data were almost certainly not available and, realistically, even cohort studies would begin after exposure. Furthermore, exposure to blast is not routinely objectively measured, so researchers had to rely on self-reported exposures. The committee preferred studies that had an independent assessment of an outcome rather than self-reports of an

outcome or reports by family members. It was preferable to have the health effect diagnosed or confirmed by a clinical evaluation, imaging, hospital record, or other medical record. For psychiatric outcomes, standardized interviews were preferred, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview; similarly, for other outcomes, standardized and validated tests were preferred. The committee recognizes that not all health outcomes have objective measures (for example, tinnitus is identified only through self-reported symptoms), that the gold standard for assessment is different for various outcomes, and that for some outcomes there may be more than one gold standard. Finally, the outcome had to be diagnosed after exposure to blast.

Many of the studies reviewed by the committee had limitations that are commonly encountered in epidemiologic studies, including lack of representative sample, selection bias, lack of control for potential confounding factors, self-reports of exposure and health outcomes, and outcome misclassification.

Although prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled studies provide the most robust type of evidence, they have not been conducted on the effects of blast in humans for ethical reasons. Few of the studies reviewed by the committee were prospective cohort studies. Rather, most were retrospective clinical record reviews and case studies and series. Many of the studies were limited by small samples and selection biases (for example, the subjects had been admitted to acute-care settings). Low response rates in studies based on survey data also were a limitation.

Studies often lacked unexposed control groups; they lacked comparisons of blast-exposed with non-blast-exposed subjects. And a number of studies compared cases of mild TBI that were associated with exposure to blast with cases of mild TBI that were not so associated, so mild TBI was a given in these study populations.

Lack of long-term followup was a limitation in most of the studies assessed by the committee. Few studies reported outcomes longer than 6 months after exposure to blast. Finally, many of the studies used self-reported outcome measures instead of objective measures.

Those types of limitations made it challenging for the committee to determine associations between exposure to blast and long-term health effects. Because of the inadequacy of epidemiologic literature that can inform long-term outcomes of exposure to blast, the committee relied heavily on the literature to assess the strength of the evidence on acute effects

and on its members’ collective clinical knowledge and expertise to draw conclusions regarding the plausibility of long-term outcomes. Some of the long-term outcomes are obvious and well documented as a consequence of the acute injuries. Other end points will require additional research studies to understand the long-term consequences of exposure specifically to blast.

The committee attempted to express its judgment of the available data clearly and precisely. It agreed to use the categories of association that have been established and used by previous committees on Gulf War and health and other IOM committees that have evaluated vaccine safety, effects of herbicides used in Vietnam, and indoor pollutants related to asthma (IOM, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009). The categories of association have gained wide acceptance over more than a decade by Congress, government agencies (particularly VA), researchers, and veterans groups.

The five categories below describe different levels of association and sound a recurring theme: the validity of an association is likely to vary to the extent to which common sources of spurious associations can be ruled out as the reason for the association. Accordingly, the criteria for each category express a degree of confidence that is based on the extent to which sources of error were reduced. The committee discussed the evidence and reached consensus on the categorization of the evidence for each health outcome (see Chapter 4).

Sufficient Evidence of a Causal Relationship

Evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a causal relationship between blast exposure and a specific health outcome in humans. The evidence fulfills the criteria of sufficient evidence of an association (below) and satisfies several of the criteria used to assess causality: strength of association, dose–response relationship, consistency of association, temporal relationship, specificity of association, and biologic plausibility.

Sufficient Evidence of an Association

Evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a positive association; that is, a consistent association has been observed between blast exposure and a specific health outcome in human studies in which chance and bias, including confounding, could be ruled out with reasonable confidence as an explanation for the observed association.

Limited/Suggestive Evidence of an Association

Evidence is suggestive of an association between blast exposure and a specific health outcome in human studies but is limited because chance, bias, and confounding could not be ruled out with reasonable confidence.

Inadequate/Insufficient Evidence of an Association

Evidence is of insufficient quantity, quality, consistency, or statistical power to permit a conclusion regarding the existence of an association between blast exposure and a specific health outcome in humans.

Limited/Suggestive Evidence of No Association

Evidence from several adequate studies is consistent in not showing a positive association between blast exposure and a specific health outcome. A conclusion of no association is inevitably limited to the conditions and length of observation in the available studies. The possibility of a very small increase in risk of the health outcome after exposure to blast cannot be excluded.

CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF BLAST INJURIES

In approaching the array of possible long-term consequences of blast injury, the committee found it useful to consider a simple conceptual model that follows service members after exposure to a blast. The model (below) demonstrates examples of long-term consequences of blast but does not depict every possible pathway.

Exposure of a service member to a blast can have several outcomes, at least in theory. Some of the outcomes are depicted in Figure 2-1, which shows the extent of disability over time. After exposure to a blast, service members can recover completely with no lasting injuries, clinical or subclinical, as depicted by the green trajectory in Panel A. Such service members do not develop long-term consequences of blast exposure. Service members can sustain acute injuries from blast exposure that results in permanent diseases and disabilities, as shown by the red trajectory in Panel A. Examples are permanent hearing and vision loss and amputation of extremities. The committee reviewed the evidence on those immediate, permanent injuries but, given its charge, focused on long-term consequences of injuries to the body from blast exposures. Service members can sustain injuries from which they seemingly recover but that initiate a constellation of adverse consequences that are not clinically obvious shortly after exposure to blast, being revealed only later, as depicted by the trajectories in Panel C. Subacute effects may

FIGURE 2-1 Examples of possible long-term consequences after exposure to blast.

NOTES: Panel A—some service members who are exposed to blast will develop acute injuries and will fully recover within a short period of time, fully recover over a long period of time, or develop chronic diseases and disabilities. Panel B—some service members who are exposed to blast will not experience acute clinically apparent injuries, but may later develop diseases or disabilities, either in the mid- or long term. Panel C—some service members who are exposed to blast will develop acute injuries and then will go on to develop chronic diseases or disabilities even though they had apparently recovered or at least partially recovered in the short term.

be detected in service members shortly after exposure to a blast. Examples of subacute effects might be electroencephalographic changes, headaches, balance impairments, and altered immune responses; these types of effects can be early symptoms of serious long-term consequences, but only sparse data are available.

Service members who do not suffer apparent initial acute injury from blast exposures may be susceptible to long-term consequences (see Panel B). Such service members, in practice in the battlefield, would be indistinguishable from the uninjured. The committee believes that it would be an error, given numerous examples in other fields, to assume that long-term conse-

quences can occur only as a result of clinically detected initial acute injuries caused by blast exposures.

The actual array of possible scenarios is far more complex than that depicted in Figure 2-1. In any service member exposed to blast, multiple organs could be affected and the result can be a constellation of short-term and long-term adverse consequences. The pathways shown in Figure 2-1 probably would intersect, and this would make prediction of long-term consequences challenging. Few data on such interactive effects are available. A key question addressed by the committee later in this report is which long-term consequences can occur only as a result of clinically detectable acute injuries and which can occur even in the absence of clinically detectable acute injuries.

Alpert, J. S., and R. J. Goldberg. 2007. Dear patient: Association is not synonymous with causality. American Journal of Medicine 120(8):E14-E15.

Evans, A. S. 1976. Causation and disease: The Henle-Koch postulates revisited. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 49(2):175-195.

Hill, A. B. 1965. Environment and disease: Association or causation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine-London 58(5):295-300.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2000. Gulf War and Health, Volume 1: Depleted Uranium, Pyridostigmine Bromide, Sarin, Vaccines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. Gulf War and Health, Volume 2: Insecticides and Solvents. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2005. Gulf War and Health, Volume 3: Fuels, Combustion Products, and Propellants. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2006. Gulf War and Health, Volume 4: Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007. Gulf War and Health, Volume 6: Health Effects of Deployment-Related Stress. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009. Gulf War and Health, Volume 7: Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 1991. Animals as Sentinels of Environmental Health Hazards. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Susser, M. 1973. Causal Thinking in the Health Sciences: Concepts and Strategies of Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Susser, M. 1977. Judgment and causal inference: Criteria in epidemiologic studies. American Journal of Epidemiology 105(1):1-15.

Susser, M. 1988. Falsification, verification, and causal inference in epidemiology: Reconsideration in the light of Sir Karl Popper’s philosophy. In Causal Inference, edited by K. J. Rothman. Chestnut Hill, MA: Epidemiology Resources. Pp. 33-58.

Susser, M. 1991. What is a cause and how do we know one?: A grammar for pragmatic epidemiology. American Journal of Epidemiology 133(7):635-648.

Wegman, D. H., N. F. Woods, and J. C. Bailar. 1997. Invited commentary: How would we know a Gulf War syndrome if we saw one? American Journal of Epidemiology 146(9):704-711.