Clinical Rationale for Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data1

Key Points Raised by the Speaker

- Health disparities among LGBT people are rooted in bias, stigma, discrimination, and social determinants of health, not genetics or other molecular issues.

- Discrimination against and substandard care for LGBT people is prevalent.

- Information about sexual orientation and gender identity is critical to addressing issues of access to care and quality of care.

- Education of clinicians, health system staff, and patients is essential to improve the collection of information on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Harvey Makadon began his talk by recognizing the Surgeon General’s report Healthy People 2020, which, for the first time, acknowledged that health disparities exist in LGBT populations. Health disparities among LGBT people are rooted in bias, stigma, discrimination, and social determinants of health, not genetics or other molecular issues, or even sexual orientation and gender identity, said Makadon. Therefore, he said, systems changes and educational changes can make a significant difference

_____________

1 This section is based on the presentations of Harvey Makadon, Clinical Professor of Medicine at the Harvard Medical School and Director of the National LGBT Health Education Center at The Fenway Institute; and Beverly Tillery, Director and Community Educator, Lambda Legal.

in the ability of the health care profession to provide quality, accessible care for LGBT people. “That is an important theme that we need to keep in mind,” said Makadon.

At one time, hospitals were taking the lead in eliminating health care disparities among minority populations, but that role is now being shared more equally by community health centers and a variety of enabling organizations. Nonetheless, hospitals continue to be a key leader in this area, and the American Hospital Association (AHA) has issued the Health Research and Education Trust Disparities Toolkit for collecting race, ethnicity, and primary language information from patients. In issuing this toolkit, the AHA noted that disparities in health care can be addressed through a quality-of-care framework if data on race, ethnicity, and primary language are available. A 2003 report from Physicians for Human Rights, The Right to Equal Treatment, reiterated this message when it stated that data collection is not only central to quality assurance but also to help ensure nondiscrimination in access to care.

Makadon said that by the same token, health disparities that affect LGBT people will only be addressed if the health system collects data on sexual orientation and gender identity. The IOM, in its report The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding, noted the direct benefit of collecting data on sexual orientation and gender identity for individual patients. Only by asking patients about their LGBT status and collecting data on the LGBT population will it be possible to end LGBT invisibility in health care. As Makadon put it, “I would say that unless we can do something about collecting data on LGBT people, we can’t assure anyone that LGBT people are receiving quality care.” He then asked the workshop audience to think about the following questions:

- Has a clinician ever asked about your sexual history, including behavior, health, and satisfaction?

- Has a clinician ever asked you about your sexual orientation?

- Has a clinician ever asked you about your gender identity?

Based on his experience, Makadon estimated that 10 to 20 percent of people would answer yes to the first question, but that close to zero would answer yes for the second and third questions. Given that there are medical issues related to sexual orientation and gender identity, it seems that it would be difficult to provide good medical care for LGBT people without that information, and it is equally challenging to assess the quality of care being provided to the LGBT population. He also remarked that the invisibility of the LGBT population results from a combination of patient reluctance to divulge information on sexual orientation or gender

identity and physician discomfort or ignorance about the importance of this information.

In terms of sexual orientation, Makadon continued, it is not simply a matter of identifying someone as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or heterosexual. Rather, he said, the real question is about how people see themselves, how they actually behave, and what their desires are. Some people, for example, are attracted to others of the same sex but have never acted on that desire, yet they want to talk to their physicians about those thoughts. “Unless you can get that information and engage people in conversation, you are not going to help somebody who is thinking about whether or not they may be gay or lesbian or bisexual, but hasn’t acted on it because they don’t feel comfortable with it. So we have to be thinking about how we get at this information,” Makadon explained.

To back up this assertion, he cited a 2006 study from the New York Department of Mental Health that found 9.4 percent of men who identified as heterosexual had had sex with a man in the previous year. These men were more likely to belong to minority racial and ethnic groups, be of lower socioeconomic status, be foreign-born, and not use a condom. In another study, between 77 and 91 percent of lesbians reported that they had at least one prior sexual experience with men, and 8 percent reported having sex with a man in the prior year. He added that while these examples might seem obvious to those attending the workshop, they are not obvious to most nurses or doctors because they do not learn about this kind of discordance between sexual identity and sexual behavior in medical school. Yet, for clinicians, it can be helpful to understand the different dimensions and manifestations of sexual orientation in order to build a better therapeutic relationship with their patients.

According to the aforementioned IOM study, lesbians and bisexual women may use preventive health services less frequently than heterosexual women. From his experience as a clinician, Makadon said that he expects that reduced access to care applies to gay men and transgender people as well. What this reduced access to care translates into, he said, is that LGBT people do not receive the right preventive health screening that they need, and the only way to remedy that situation is to identify these populations.

As an illustration of the importance of identifying LGBT people, Makadon cited 2009 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that showed that 61 percent of new cases of HIV infection were among men who have sex with men. This number, which has been climbing annually since 2006, came as a surprise given that the number

of HIV cases overall remained constant, and it likely reflects the fact that prevention efforts are not reaching men who have sex with men but do not identify as gay when asked on a survey. This is particularly true among black men between the ages of 13 and 29 who have sex with men, a population in which there has been an almost 50 percent increase in the incidence of HIV cases between 2006 and 2009.

These data highlight the fact that LGBT people are not one homogeneous group, but rather that they reflect the same cultural diversity seen throughout the general population. Understanding the cultural diversity among, in this case, men who have sex with men, is going to be key to developing ways to reach underserved populations, but that lesson applies to all LGBT people, said Makadon. That understanding cannot start without data about these underserved populations.

In terms of understanding the T in LGBT, the IOM report noted that there are significant health disparities that have been documented among transgender people. It is critical that clinicians have information on a patient’s gender identity, gender expression, birth sex, medical history, and current anatomy. The only way to get this information is by educating both clinicians and the transgender community about the importance of discussing these issues to ensure access to high-quality care. The clinician, said Makadon, has to be the point person in gathering this information, but the field needs to figure out ways to help clinicians so that they do not spend all of their time just gathering data and not having time to talk to their patients.

To illustrate the importance of all clinicians, not just the primary care physician, having information about a patient’s gender identity, Makadon discussed two case studies. The first case involved a 50-year-old woman who developed a high fever and chills after head and neck surgery. The infection source turned out to be the patient’s prostate gland, which nobody knew she had because nobody had asked about her gender identity and she had not volunteered this information. She could have received much quicker treatment for her infection had her surgeon and the hospital staff known she was a transgender woman.

The second case involved a 55-year-old man who came to his physician with pain and on X-ray appeared to have metastases from an unknown primary cancer. Evaluation ultimately showed that he had developed cancer in his residual breast tissue that remained after having “top surgery” to remove his breasts. None of his physicians were aware that he was a transgender man, so he had not been advised to have routine breast screening even though his mother and sister had also had breast cancer.

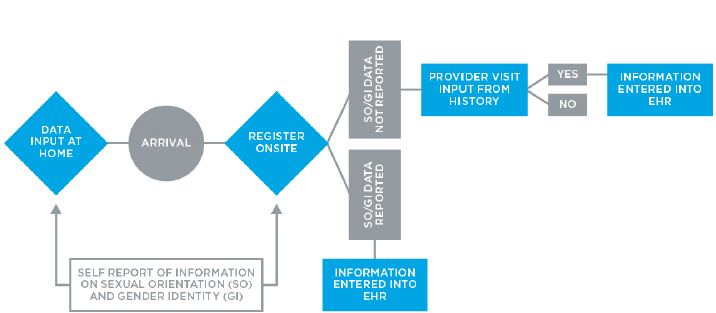

Makadon then discussed some of the new opportunities that exist for gathering patient information on sexual orientation and gender identity that take advantage of patient portals that many health care systems have now installed (Figure 2-1). These portals are designed to enable patients to input information about themselves in the privacy of their homes, which could be particularly important for LGBT people. Another approach that some health care systems are testing is to use iPads handed out at the registration desk to enable patients’ to enter data in private, rather than as verbal answers to what can be embarrassing or awkward questions. That information can then become part of the electronic record that all of an individual’s clinicians would have access to without the need to question the patient.

In closing, Makadon said that there are a few issues that need to be considered in preparation for collecting LGBT data in clinical settings. Clinicians, he said, need to learn about LGBT health issues and the range of expression related to identity, behavior, and desire. Health care system staff members also need to understand these concepts given that patients often report that uncomfortable questions come up at the reception desk, not in the exam room. Patients, too, need to learn about why it is important to communicate this information and to feel comfortable that it will be used appropriately. Finally, collecting data on sexual orientation and gender identity is critical and has to be done sensitively, without assumptions, and for every patient along with all other demographic data. “Our task is to improve quality and access to care for all, including LGBT people, and that starts with more data collection,” said Makadon.

SUPPORTING PATIENTS IN THE COLLECTION OF DATA

In 2009, Lambda Legal, together with more than 100 partner organizations, surveyed 4,916 people representing a diverse sampling of LGBT communities and people living with HIV, regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity, HIV status, race, ethnicity, age, and geography. The resulting report, When Health Care Isn’t Caring: Lambda Legal’s Survey on Discrimination Against LGBT People and People Living with HIV, was the first to document refusal of care and barriers to health care among LGBT and HIV communities on a national scale, said Beverly Tillery. She added that the findings were surprisingly high in terms of discrimination and substandard care. For example, 56 percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual individuals and 70 percent of transgender

people said that they had experienced discrimination or received substandard care. Nearly 8 percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and almost 27 percent of transgender people reported being refused needed health care. More than 10 percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and more than 15 percent of transgender people reported having had the experience of a health care professional who refused to touch them or used excessive precautions before touching them. Almost 11 percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and almost 21 percent of transgender people said that they had experienced a health care professional use harsh or abusive language with them and 4 percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and almost 8 percent of transgender people described receiving physically rough or abusive treatment from a health care professional. In nearly every case, people of color and low-income people had higher rates of experiencing discrimination.

In terms of barriers to care, the survey found that significant percentages of LGBT individuals expressed concerns about accessing health care. Nine percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and almost 52 percent of transgender people feared they would be refused medical service; more than 28 percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and 73 percent of transgender people expressed concern that medical personnel would treat them differently than non-LGBT people; 49 percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and almost 90 percent of transgender people said there were not enough health professionals who were adequately trained to care for them because of their sexual orientation or gender identity status; more than 24 percent lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and more than 50 percent of transgender people said there were not enough support groups; and almost 29 percent of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people and almost 59 percent of transgender people said there were not enough substance abuse programs for LGBT individuals. Again, the numbers were all higher in people of color.

As part of this project, Lambda Legal and its partners also collected 50 personal stories that provided real-life illustrations of the discrimination and substandard care LGBT people experience. Among the stories that Tillery recounted were

• Jodi from Atlanta, who had to seek emergency room care. “The nurse comes into the room to get my information. Among her list of questions was whether I was single or married. Well, I had a union that was not recognized in Georgia, but it would not have been accurate to answer either single or married. The nurse wanted an emergency contact and wanted to know if there was anyone with me, and if so, what was their relationship to me. I panicked for a minute.

“I was scared to admit my life partner was in the waiting room. I was mortified to say I was single. My head was swimming trying to think of a lie about who my partner was. Should I be safe and say she was a friend? If so, she would be denied visitation if something went wrong. Should I lie and say she was my sister?

How humiliating. I was afraid that if I admitted to being gay with a partner that I might get sub-par care and even have my care and life sabotaged.

“After delaying, I felt I would take the risk and say that my relationship does not fit into one of the boxes on your form. When the nurse looked confused, I confessed that I was gay and that my life partner was in the waiting room. She looked confused again, and after a pause, said, ‘Uh, oh, huh, never heard that before.’ Luckily, that is the worst that happened, but no one should have to go through even that much.”

• Joe from Minneapolis. “I was 36 years old at the time of this story and an out gay man. I was depressed over the breakup of an 8-year relationship. The doctor I went to see told me that it was not medicine I needed, but to leave my dirty lifestyle.”

• Emile in Boise. “I’m a post-operative trans woman who began my gender transition in 2004. After talking about transitioning with my family M.D., she agreed to continue her medical relationship with me. Because she was not experienced with treating a trans person or prescribing hormone replacement therapy, she referred me to a local endocrinologist. When I called to set up an appointment, I was told by the secretary, we don’t treat people like you. I called two other local endocrinologists and was told the exact same thing.”

• Tory from Portland. “I went to visit my school’s health clinic for an annual check-up. While I was filling out my health history information sheet, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the sheet indicated both male and female partners, the number of partners, and the type of birth control I used. I thought this was a great example of LGBT-friendly medical facilities. Unfortunately, when I was called into the exam room, the nurse didn’t read the form and proceeded to ask me if I was sexually active and used condoms. “When I replied no and told the nurse that I was a lesbian, she was shocked. After that, the appointment was awkward, and I felt as though the nurse was not willing to touch me because I was a lesbian. The entire awkward conversation and exam could have been avoided if the nurse had only read the information sheet she was given. It just goes to show you that having an LGBT-friendly question form does not make a clinic LGBT-friendly.”

• Lee from Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. “Fortunately, my primary care physician is awesome. She takes good care of me and has since I was 15 years old. I am able to completely be out and honest with her. Although we may not always agree on non-treatment-related topics, she is fair and non-judgmental. Unfortunately, I have been

subjected to ignorance by specialists, female gynecological specialists, and one male plastic surgeon.

“One simply refused to believe that I was not sexually active with men and refused to believe that I did have sex with women. Others struggle with my identity. I identify primarily as male, but I still have to cope with having a female body and keep it healthy. I’m blessed to be healthy these days. I have never been evasive about my person, and I have found that when I’m able to openly discuss my body and my life, I am able to make informed, rational, and essential decisions about my health.”

In closing, Tillery emphasized the critical need to gather information in order to identify health care disparities in LGBT communities. It is clear from the data that Lambda Legal collected, she said, that LGBT people experience real discrimination and a significant level of it, which makes them cautious about getting the health care they need. It is also important, she added, to focus on confidentiality and privacy because privacy breaches can have repercussions that go far beyond health care. In many states, she reminded the audience, it is still legal to be fired for being LGBT. She recommended that data collection be optional with a sense of informed consent that involves educating patients about why these data are important, and how and when they will be used.

During the discussion session, Makadon was asked if the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) or electronic health record system vendors were working on developing requirements and standards for the collection of this information. Robert Tagalicod, from CMS, answered that both his agency and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) are working closely with the vendor community to develop certification standards. Makadon said that from his understanding, the issues are not technical ones but involve defining the questions that need to be asked and structuring those questions appropriately. As an example, he said that while it is important to ask about gender identity, it is equally important to ask birth sex in order to have accurate information about a patient’s anatomy.

It is also important, he added, to think about these questions in a way that works for transgender people but also for everyone else so that everyone feels comfortable that these are routine questions that are being asked because they are important for the health care of a significant number of individuals. He recounted the furor that arose when Massachusetts instituted a requirement to collect data on race and ethnicity because most

people did not understand the need for this information. Now, the public understands, for example, that untreated high blood pressure is more prevalent in the African American community.

Leslie Calman, of the Mautner Project: The National Lesbian Health Organization, asked if Makadon had any insights into how to communicate these issues to her community. She noted that she regularly encounters lesbians, particularly older lesbians, who are terrified of having this information available and are particularly terrified that they will find themselves in a situation where they have an accident, go to the hospital, and receive poor care because they are lesbians. Makadon agreed that this fear is real in the LGBT community, particularly among older individuals. In a final comment, Jesse Ehrenfeld, from Vanderbilt University, noted that a prospective clinical trial that he and his colleagues recently finished showed that patients are more honest about their personal information when they provided it at home.