In the 1949 film The Third Man and the novel of the same name, Holly Martin learns that his childhood friend Harry Lime has made a fortune diluting stolen penicillin and selling it on the black market. In a dramatic confrontation on the Vienna Ferris wheel, Martin refers to Lime’s earlier racketeering, asking, “Couldn’t you have stuck to tires?” No, explains Lime, one of the American Film Institute’s 100 greatest villains, “I’ve always been ambitious” (AFI, 2003).

The theft, adulteration, careless manufacture, and fraudulent labeling of medicines1 continue to attract villains who, like Harry Lime, grow wealthy off their business. Although the problem is most widespread in poor countries with weak regulatory oversight, it is no longer confined to underground economies as in postwar Vienna. As of January 2013, gross manufacturing negligence at a compounding pharmacy in Massachusetts had sickened 693 Americans and killed 45 (CDC, 2013). Less than a year earlier, 76 doctors in the United States unknowingly treated cancer patients with a fake version of the drug Avastin (Weaver and Whalen, 2012).

International trade and manufacturing systems obscure connections between the crime and the criminal; in modern supply chains, medicines may change hands many times in many countries before reaching a patient. To complicate the problem, medicines are mostly for sick people. The effects of inactive, even toxic, drugs can go unnoticed or be mistaken for the

______________________

1 The terms medicine, drug, and pharmaceutical are used interchangeably in this report in accordance with the definitions listed in the American Heritage Stedman’s Medical Dictionary (2012a,b,c).

natural course of the underlying disease. This is most true in parts of the world with weak pharmacovigilance systems, poor clinical record keeping, and high all-cause mortality, where “friends or relatives of those who die are obviously saddened, but not necessarily shocked” (Bate, 2010).

Deaths from fake drugs go largely uncounted, to say nothing of the excess morbidity and the time and money wasted by using them. The manufacture and trade in fake pharmaceuticals is illegal and hence almost impossible to measure precisely. Even crude copies can blend in with legitimate products in the market. The camouflage succeeds because drug quality is not something consumers can accurately judge. This imbalance, also called information asymmetry, makes the medicines trade vulnerable to market failure (Mackintosh et al., 2011). In short, “At every step of the supply chain there is this unequal knowledge, and people are exploited because of [it]” (Mackintosh et al., 2011, p. 2).

Market controls and oversight aim to correct the information imbalance in the medicines market, but supervising sprawling multinational distribution chains is a “regulatory nightmare” (Economist, 2012). National drugs regulatory agencies (hereafter, regulatory agencies) are responsible for assuring drug quality in their countries, a job that increasingly requires cooperation with their counterpart agencies around the world (IOM, 2012). The World Health Organization (WHO) has worked to facilitate this cooperation since 1985, but advancing the public discourse on this topic has proven more difficult than anyone would have predicted then (Clift, 2010).

To start, different countries and international stakeholders cannot agree on how to define the problem. When it is framed as one of counterfeit and legitimate drugs, many civil society groups and emerging manufacturing nations see a thinly veiled excuse to persecute generic drug industries (Clift, 2010; Economist, 2012). Large innovator pharmaceutical companies have the most experience in finding and prosecuting pharmaceutical crime. This expertise brought them a place in the WHO’s International Medical Products Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce (IMPACT), the largest international working group on drug safety to date. Involving these companies with a WHO program, however, raised suspicions of civil society groups (TWN, 2010). Objections to the taskforce’s inception and confusion about its mandate from WHO governing bodies further eroded support (TWN, 2010). The WHO distanced itself from IMPACT after 2010; the taskforce’s secretariat moved to the Italian drugs regulatory authority (Seear, 2012; Taylor, 2012).

IMPACT may no longer be active, but criminals and unscrupulous drug manufacturers are. The Economist recently described the 21st century as “a golden age for bad drugs” (Economist, 2012). There is an urgent need for international public discourse on the problem. In an effort to advance this discourse, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) commissioned

the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to convene a consensus committee on understanding the global public health implications of falsified, substandard, and counterfeit pharmaceuticals. Box 1-1 presents the committee’s charge. (See Appendix B for committee member biographies.)

The committee met in March, May, July, and October of 2012 to hear speakers and deliberate on its recommendations for this report. Small travel delegations of committee members and staff also visited experts in Brasília, Delhi, Geneva, Hyderabad, London, and São Paulo in the summer of 2012. In total, the committee heard input from 106 experts in its information gathering meetings. (See Appendix C for meeting agendas.) Additional literature review informed the conclusions and recommendations presented in this report.

The committee’s first step in deliberating on the task in Box 1-1 was agreeing on common terms to describe the products of interest. They reviewed the competing and often overlapping definitions of the terms counterfeit, falsified, and substandard, as well as similarly important concepts such as unregistered. As Tables 1-1 through 1-6 make clear, some of these definitions have evolved over time, with the trade and intellectual property debates of the last 20 years coloring how people use words like counterfeit. The following brief background on intellectual property, public health, and patent and trademark infringement gives some context to this discussion.

Key Findings and Conclusions

• A long and acrimonious history of applying intellectual property rights to medicines colors the discussion about drug quality.

• A counterfeit medicine is one that infringes on a registered trademark. The broad use of the term counterfeit, meaning made with intention to deceive, is insufficiently precise for formal, public discourse.

• Substandard drugs fail to meet the specifications outlined by an accepted pharmacopeia or the manufacturer’s dossier.

• Falsified drugs are those that carry false representation of identity or source.

• Unregistered drugs circulate without market authorization. Unregistered medicines are suspect, though some may be of good quality.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) is requested to convene an ad hoc consensus committee of diverse experts to gather information and deliberate on approaches to mitigating the global problem of substandard, falsified, and counterfeit pharmaceuticals and products used in their manufacture. It will begin by developing among the committee members and for this context consensus working definitions for the terms substandard, falsified, and counterfeit. The committee will carefully distinguish between the application of these terms to meet public health and legal needs. Then, focusing specifically on the public health aspects of the problem, the IOM committee will address the following issues:

• Trends: Using available literature, identify high-level, global trends in substandard, falsified, and counterfeit (SFC) medicines, including differences and similarities in different global regions. Identify gaps in the evidence that complicate the analysis of these trends. This is intended to provide context to the study but not to serve as an in-depth analysis.

• Risks in the supply chain: Identify the weaknesses in the supply chain that allow falsified, substandard, and counterfeit drugs to circulate.

• Health effects: Explain the public health consequences, to patients and at the population level, of SFC drugs and how to measure this.

• Standards: Identify areas where convergence of standards could contribute to stronger regulatory actions.

Intellectual Property and Public Health

Intellectual property rights, particularly patent rights, allow the owner of a new product or technology to recoup their research and development costs by charging prices far above the marginal cost of production. Therefore, patent-protected medicines are expensive; the cost of these drugs puts them out of the reach of many patients. In developed countries, governments or large private insurers can mitigate this problem (Rai, 2001). But in poor countries, health insurance is limited and noncompetitive pricing can exclude entire countries from the medicines market (Yadav and Smith, 2012).

TRIPS and the Doha Declaration

The recent history of the international patent controversy began with the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property

• Identification: Describe global regulatory processes (e.g., track-and-trace, authentication) that distinguish genuine and highquality drugs from fake or substandard drugs and identify what factors could be used for additional scrutiny of the genuineness of the product.

• Technology: Identify detection, sampling methods, and analytical techniques used to identify counterfeit, falsified, and substandard drugs. Explain how these technologies can be best used and implemented in a system to stop the circulation of harmful drugs.

• Collaboration: Assess effectiveness of regulatory approaches around the globe, including prevention, detection, track-andtrace systems, compliance, and enforcement actions.

o Based on such an assessment, identify areas where collective action among government regulatory authorities is most relevant and sustainable;

o Identify ways government, industry, and other stakeholders can work together to strengthen supply chains and fight counterfeit, falsified, and substandard drugs;

o Identify areas where industry or other stakeholders are best equipped to act; and

o Recommend a collaborative path forward. This includes recommending definitions for the products in question that would be sensitive to the needs of drug regulators around the world and focuses on the public health. It also includes recommending how various regulators could collaborate on a global and regional level to best address the problem.

Rights (TRIPS), which required signatories to make patents available, either immediately or after a transition period (Barton, 2004; WTO, 1994). However, a provision allowed governments to grant compulsory licenses, that is, to grant a license to use a patent without the patent holder’s consent, subject to conditions laid down in the agreement (WTO, 1994). Compulsory licenses are subject to prior negotiation with the patent holder, but these negotiations too can be waived in cases of national emergency or extreme urgency or for public noncommercial use (WTO, 1994).

As TRIPS entered into force, antiretroviral drugs for HIV and AIDS were becoming widely available in developed countries, reducing AIDS mortality dramatically within 4 years (CASCADE Collaboration, 2003; Osmond, 2003). The expense of the patent-protected drugs put them out of reach for all but 2 percent of the approximately 2.5 million HIV and AIDS patients in low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 2002). Tensions over patent protection came to a head in 2001 when the Pharmaceutical

Research and Manufacturing Association, representing 39 major pharmaceutical companies, sued the South African government over a law that allowed the manufacture of patent-protected AIDS drugs (BBC, 2001a; Simmons, 2001). The association “bow[ed] to mounting public pressure” and dropped the case after disastrous press (BBC, 2001b; Economist, 2001; Pollack, 2001; Swarns, 2001). After 2001, innovator drug companies began issuing more voluntary licenses at lower prices (Flynn, 2008).

Antiretrovirals would still have been too expensive for the poorest patients if not for Indian drug companies, exempted from TRIPS patent protections until 2005. In February 2001, the Indian drug company Cipla offered its triple therapy combination of stavudine, nevirapine, and lamivudine to Doctors Without Borders (an organization known by the French acronym MSF [Médecins Sans Frontières]) for less than $1 per patient per day, undercutting the cheapest voluntary license offer by about 65 percent (McNeil, 2001; t’Hoen et al., 2011).

More recently, regulators and innovator pharmaceutical companies have devised other ways to make patent-protected drugs available in developing countries. The U.S. government uses the FDA tentative approval process to guarantee drugs supplied through the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (FDA, 2013). Through this program, the FDA approves both drug combinations (many not available in the United States because of patent controls) and the producers in Asia and Africa that make the drugs at greatly reduced costs (FDA, 2013). Drugs granted tentative approval “[meet] all safety, efficacy, and manufacturing quality standards for marketing in the U.S., and, but for the legal market protection, … would be on the U.S. market” (FDA, 2013).

Patent and Trademark Infringement

Patents, not trademark or trade dress, are the main source of tension between intellectual property and public health. But both patent and trademark questions surfaced in 2008 and 2009 when European customs officials seized consignments of generic medicines in transit from India to Latin American and sub-Saharan Africa (Brant and Malpani, 2011). The drugs were not under patent in India, nor in the counties they were destined for, but a European Union (EU) regulation allows customs officials, acting either on their own behalf or after a request from the rights holder, to seize goods that may infringe on patents, trademarks, or copyrights (Ho, 2011; Miller and Anand, 2009). Dutch courts interpreted this to mean that customs authorities are allowed to treat in-transit goods as if they had been made in Holland (Ho, 2011). French and German customs officials also seized drug shipments in the same period (Taylor, 2009).

Sometimes trademark misunderstandings delay consignments. In May

2009, German authorities suspended a shipment of amoxicillin bound for Vanuatu in the Frankfurt airport on the grounds that it might infringe on GlaxoSmithKline’s trademark name for the same drug, Amoxil. When contacted, GlaxoSmithKline denied any suspicion of trademark infringement, by which time the shipment had been delayed for 4 weeks (Mara, 2009; Singh, 2009).

Whether the use of national law to seize in-transit drug shipments is consistent with international law, particularly the TRIPs agreement, remains an open question (Ho, 2011; Ruse-Khan, 2011). Developing countries argue that such seizures violate TRIPs agreement safeguards allowing the export of cheap generic drugs to countries unable to manufacture them (Ho, 2011). On the other hand, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, signed by Australia, Canada, the European Union, Japan, Korea, Morocco, New Zealand, Singapore, and the United States, does allow parties to enforce their national trademark law against goods-in-transit, thereby potentially endangering certain generic shipments2 (USTR, 2011).

In any case, there are ambiguities in determining trademark infringement. U.S. law, for example, determines trademark infringement based on likely consumer confusion, something the 13 federal circuits employ 13 different multifactor tests to identify (Beebe, 2006). Drug trademarks can be contentious when companies register trademark names similar to the nonproprietary name (as in the case of Amoxil and amoxicillin) and when drug manufacturers attempt to trademark characteristics such as color.

TRIPS requires World Trade Organization (WTO) member countries to treat “willful trademark counterfeiting … on a commercial scale” as a criminal offense3 (Clift, 2010). This kind of crime may be different from the civil offense of trademark infringement, if the willfulness of the crime is unclear, for example, or if the trademark is not identically copied (Clift, 2010). These distinctions are not important to some stakeholders. As a 2011 Oxfam policy paper explained, “whether a falsely labeled, substandard, or unregistered product is also the result of willful trademark infringement on a commercial scale, as criminalized under the TRIPS Agreement, is irrelevant from the perspective of public health” (Brant and Malpani, 2011, p. 23).

Oxfam’s point is well taken. The goals of patent and trademark law are not those of public health. Trademarks can give an incentive to invest in quality and cultivate a brand loyalty, but this depends on consumers’ evaluating

______________________

2 Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA). October 1, 2011.

3 TRIPS: Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Apr. 15, 1994, Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, Annex 1C, THE LEGAL TEXTS: THE RESULTS OF THE URUGUAY ROUND OF MULTILATERAL TRADE NEGOTIATIONS 320 (1999), 1869 U.N.T.S. 299, 33 I.L.M. 1197 (1994).

quality correctly, something difficult to do with medicines (Landes and Posner, 1987). The inability of the consumer to evaluate drug quality is the reason why medicines quality is monitored by an independent, government regulatory agency. The courts enforce trademark and patent laws; drugs regulators enforce quality standards. It is unreasonable and unfair to mix those jobs. Such was the logic of the International Negotiating Body on a Protocol on Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products, which recently removed all references to counterfeits from its treaty, noting that decisions about trademark infringement in tobacco products was not within their purview (New, 2012).

The committee recognizes that many poor-quality medicines also infringe on registered trademarks. At times, trademark infringement can become a public health problem, but it is not a public health problem in itself, even insomuch as it pertains to medicines.

Competing Meanings of the Term Counterfeit

The contentious history of drug patent and trademark enforcement colors discussions of drug quality, particularly the use of the term counterfeit. The U.S. Code, the WTO, the TRIPS Agreement, and Oxfam all use the legal meaning of a counterfeit medicine as one that infringes on a registered trademark (Brant and Malpani, 2011; Clift, 2010; WTO, 1994, 2012). Nevertheless, the word counterfeit, like material and harmless, means one thing to lawyers and judges and something else in common discourse. It is the widely used common meaning of counterfeit as “made in exact imitation of something valuable with the intention to deceive or defraud” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2012) that inspires the way the term is used by the WHO, the Pharmaceutical Security Institute, the Council of Europe, and the governments of India, Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, and, in some cases, the United States (see Table 1-1). The WHO definitions of counterfeit lean on the intent to deceive; Table 1-1 shows how most WHO definitions use the words “deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled.”

There is elegance to a definition that stresses the intention to deceive. Its proponents rightly observe that this is what most people understand the word to mean anyway. This definition has at its center the effort to distinguish between deliberate and accidental problems. The manufacturer is not to blame if a drug is sold after the expiry date or if it has been kept in conditions that encourage rapid degradation. The 2008 contamination of Baxter heparin was a reminder that even expert companies sometimes produce bad products, but the failure was not intentional (Attaran and Bate, 2010). The regulatory system typically punishes such mistakes, whereas the law enforcement system punishes intentional crimes.

In practice, however, it is extremely difficult to distinguish accidental

and intentional problems in drug manufacture. Making the distinction, like determining trademark infringement, is a matter for the courts. Furthermore, competing meanings of the word counterfeit—one narrow, meaning infringement on a registered trademark, and one broad, meaning intentionally deceptive—frustrate many.

When bad drugs are all called counterfeit, some see in this definition an attempt to conflate the enforcement of intellectual property rights and protection of public health (Brant and Malpani, 2011; Clift, 2010; MSF, 2012; Oxfam International, 2011; TWN, 2010). International nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as Oxfam and MSF, are concerned with access to medicines in the world’s poorest countries, access that cannot be possible without the generics companies that produce medicines for a fraction of the cost innovator companies charge. Generics companies may be vulnerable to accusations of trademark infringement or even deception. When a generic and an innovator drug company market bioequivalent medicines under similar-sounding names or with similar-looking pills, it is debatable whether or not these characteristics are copied or made with an intention to deceive the consumer. These are questions for the courts to decide case by case.

Counterfeit is a word that almost everyone uses to talk about bad medicines, but as Tables 1-1 and 1-2 indicate, often with widely divergent meanings. The ambiguity confuses discussions even within governments. The FDA, for example, endorses on its website a definition different from that in the U.S. Code or that used by the Department of Justice and other U.S. government agencies. The use of the word counterfeit to describe any poor-quality drug does not serve the cause of intellectual precision or productive discussion. The committee accepts the narrow, legal meaning of a counterfeit drug as one that infringes on a registered trademark. Trademark infringement is not a problem of public health concern, nor, in most cases, is it even readily identifiable. Drug companies, both innovator and generic, have the legal right to challenge counterfeiting; sorting out the nuances of trademark infringement should be left to the courts.

This report is about drug quality as a public health problem; it is not concerned with trademark infringement. Therefore, this report does not discuss the problem or solutions to the problem of drug counterfeiting, or make mention to counterfeit drugs, except in cases where to do otherwise would be a misrepresentation of someone else’s work. Scientific literature and public health campaigns, especially those more than 2 or 3 years old, often describe poor-quality drugs as counterfeit. The committee hopes that all parties will break this habit but believes that most speakers who use the term use it broadly with no ulterior motives or ill will toward generics.

Substandard and Falsified Drugs

Use of the term substandard is less controversial (see Tables 1-3 and 1-4). There is consensus among most organizations that substandard drugs are those that fail to meet established quality specifications. When regulators approve a drug, they approve a quality standard, outlined in the accepted pharmacopeia or in the manufacturer’s approved dossier. As the WHO explains, substandard products “do not meet the quality specifications set for them in national standards” (WHO, 2009).

As Table 1-3 indicates, the emphasis on national standards is a relatively recent change to the definition of a substandard drug. Before 2009, the emphasis was on an official pharmacopeia, not the national standard. Critics of the addition point out that the regulatory authority is responsible for approving national drug standards, a job that exceeds its capacity in many low- and middle-income countries (Ravinetto et al., 2012). Accepting the national standard might appear to endorse multiple, possibly inadequate standards (Ravinetto et al., 2012).

On the other hand, an emphasis on national standards improves the precision of the definition. There are many internationally accepted pharmacopeias; some give, for example, different acceptable ranges for drug concentration.4 The committee agrees with the WHO’s 2009 revision to the definition of substandard to specify the standards authorized by the national regulatory authority. It is more practical to let the national regulatory authority name the standard for a drug and test against that standard. In any case, most countries use standards set out in the large, international pharmacopeias. More than 100 nations, including most of the Commonwealth, accept British Pharmacopoeia standards (GIZ, 2012); 140 recognize the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP, 2013), and 37 the European Pharmacopoeia (Council of Europe, 2013). (Some countries reference different pharmacopeial standards for different drugs and may therefore officially use more than one pharmacopeia.)

Some understandings of a substandard medicine emphasize the manufacturer’s market authorization. (See Table 1-3.) This distinction becomes important when a substandard product is found in commerce. The regulatory agency can then take corrective action with the manufacturer and recall other products from the same batch. During this process, the manufacturer may prove with verified records and batch samples that the poor-

______________________

4 For amodiaquine hydrochloride tablets, the acceptable drug concentration range under U.S. Pharmacopeia is 93 percent to 107 percent of labeled amount (USP, 2011a); under International Pharmacopoeia it is 90 percent to 110 percent (WHO, 2011c). For quinine sulfate tablets, the acceptable drug concentration range under U.S. Pharmacopeia is 90 percent to 110 percent of the labeled amount (USP, 2011b); under British Pharmacopoeia, it is 95 percent to 105 percent (British Pharmacopoeia, 2012c).

quality drug is not in fact its own. In such a case, the manufacturer is the victim of fraud. The drug in question was falsified and therefore in the domain of law enforcement.

The committee considers a drug falsified when there is false representation of the product’s identity or source or both. Falsified medicines may contain the wrong ingredients in the wrong doses. A fake product in legitimate packaging is falsified, as is a good-quality product in fake packaging (EMA, 2012). The producer’s intention is theoretically important to the understanding of a falsified drug, though in practice it is often impossible to known what these intentions were. That is, when a licensed manufacturer makes bad drugs, the deliberateness of the mistake is at least debatable. When an underground producer makes a bad-quality product there is not even a pretense of adhering to drug quality standards. This understanding of a falsified medicine is consistent with the broad definition of counterfeit used by WHO and other organizations. A falsified drug may also be called fake, a synonym used in this report and by some scholars, governments, and international NGOs (Bate, 2011; Björkman-Nyqvist et al., 2012; MSF, 2012; Newton et al., 2011). (See Table 1-5.)

Often, the difference between a substandard and a falsified medicine is the difference between a known and unknown manufacturer. Manufacturers may produce substandard drugs because they failed to adhere to good manufacturing practices or because their internal quality systems failed. Degraded or expired products are also substandard; in some ways, failure to pull these drugs from the market is a quality system failure. Inspection of the manufacturer’s records can usually distinguish between a degraded or expired drug and one that left the factory already outside of specifications.

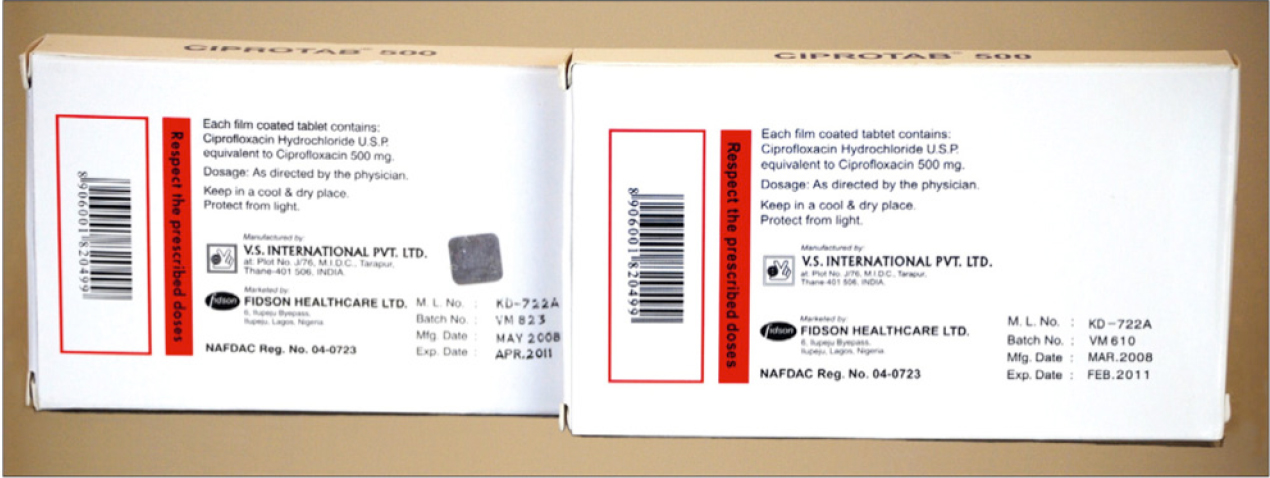

Falsified drugs are usually also substandard. Drug regulators have no authority over underground manufacturers; nothing can be said about

The Indian generics house V.S. International’s authentic ciprofloxacin (left) and a falsified version (right).

SOURCE: Bate, 2012b.

their quality controls or adherence to good manufacturing practices. It is unlikely, though not unheard of, that an illegal manufacturer would go to the trouble of making a quality-controlled medicine from quality-assured substrate.

Distinguishing between falsified and substandard drugs is a necessary first step when discussing the problem in any depth. It is admittedly something of an academic exercise, though. In many parts of the world, drugs are sold without proper packaging and emphasis on label claims has no practical value. Details of the pharmacopeial standard can also cause confusion. The U.S. Pharmacopeia, for example, gives a dissolution standard; the British Pharmacopoeia, widely used in the Commonwealth, often does not (British Pharmacopoeia, 2012b; Paleshnuik, 2009). A drug that does not dissolve is substandard nonetheless. Critics of these definitions might also point out that drug labels usually reference the pharmacopeial standard. Therefore, failing to meet the standard is also a false representation.

The definitions proposed can inevitably be caught on exceptions, but the committee believes that public discourse is best advanced by considering two main types of bad drugs: falsified and substandard. This report aims to set out useful, general terms for public discussion. Defining the products of interest is valuable only insomuch as it advances the discussion of the root causes and solutions of the problem; making definitions is not an end in itself.

Similarly, the lumping together of many competing and contradictory terms with unwieldy acronyms such as SSFFC (short for substandard, spurious, falsified, falsely labeled, and counterfeit) only encourages confusion. Speakers seeking a parent category for substandard and falsified drugs could consider illegitimate or even bad, but not SSFFC (Attaran et al., 2012).

The Problem of Unregistered Medicines

Medicines registration is one of the main responsibilities of a drugs regulatory authority (Ratanawijitrasin and Wondemagegnehu, 2002), which maintains the medicine register, “a list of all the pharmaceutical products authorized for marketing in a particular country” (WHO, 2011b, p. 43). The regulatory authority issues a market authorization, proof of entry to the medicines register, to the manufacturer of any medical product sold or distributed for free in a given country (SADC, 2007). Market authorization documents usually include the name and address of the manufacturer and information about the registered product (SADC, 2007).

Maintaining an accurate medicines register is difficult in developing countries, where the regulatory authority is often understaffed and underfunded (IOM, 2012; Ratanawijitrasin and Wondemagegnehu, 2002). To

complicate the problem, medicines travel quickly among small, landlocked countries with porous borders. The WHO found about 1,000 unregistered drugs on the Cambodian market, for example (WHO, 2003b). The amount of unregistered products on the market is also unpredictable. Sometimes bilateral trade negotiations end in large shipments of unregistered medicines in a country (Morris and Stevens, 2006; Newton et al., 2010).

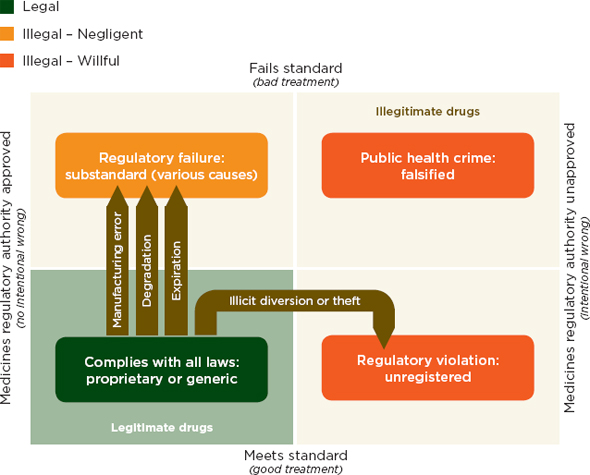

In a conceptual illustration of the problem, Attaran and colleagues show that unregistered drugs may be of good quality (see Figure 1-1). This figure shows drug quality standards on the y-axis and registration on the x-axis. In this framework, drugs that fail to meet the regulatory authority’s standards are divided into failures of negligence (substandard drugs) and willful failures (falsified drugs). This diagram separates the good-quality unregistered medicines from other types of illegitimate drugs. In practice, however, the distinction is not always clear.

Some research suggests that unregistered medicines can be dangerous.

FIGURE 1-1 A two-dimensional description of medicine quality and registration.

SOURCE: Attaran et al., 2012. Reprinted with permission from BMJ Publishing Group.

A field survey of uterotonic drug quality in Ghana found that all unregistered drug samples tested were substandard; one of the unregistered products contained no active ingredient at all (Stanton et al., 2012). Many of the samples might have degraded during disorganized transport, but the explanation is never clear with unregistered drugs.

Unregistered medicines are vulnerable to quality failures. They do not enter the market through reputable channels and are often transported under poor conditions. These problems can easily go undetected. Postmarket surveillance is, by definition, a way to monitor the safety of those drugs authorized for a particular market. Therefore, the quality failures of unregistered medicines resist detection in postmarket surveillance (Amin and Snow, 2005). The proliferation of unregistered medicines suggests problems with the market authorization process in a country and, more generally, with regulatory oversight. Although unregistered drugs are not by definition falsified or substandard, they are conceptually related and part of the problem.

The lack of a consistent vocabulary has held back public discourse on the problem of poor quality medicines in the market. As Tables 1-1 through 1-5 indicate, different countries often have widely different interpretations of the same terms, creating a confusion that holds back international cooperation (Clift, 2010). Defining a common vocabulary is important, not just for this report but for all discourse on the topic.

Box 1-2 presents the definitions of the terms falsified, substandard, counterfeit, and unregistered used in this report. As this chapter explains, distinguishing between substandard and falsified medicines in the field can be difficult. In practice, there is often considerable ambiguity in real-life examples of unlabeled, poor-quality drugs. Nevertheless, falsified and substandard are good categories to describe problems with poor-quality drugs. Consistent use of these terms would ease the measuring of trends, analysis of causes, and discussion of proposed solutions to the problem.

Recommendation 1-1: The World Health Assembly should adopt definitions consistent with the following principles. Substandard drugs do not meet national specifications.5 Falsified products have a false representation of identity or source or both. Products unregistered with the regulatory authority are also illegal.

______________________

5 An emphasis on quality system failures is not essential to the idea of a substandard drug and was removed from the recommendation after the report release. The supporting text describes the committee’s understanding of a substandard drug.

Counterfeit: A counterfeit drug bears an unauthorized representation of a registered trademark on a product identical or similar to one for which the trademark is registered.

Falsified: A falsified drug is one that falsely represents the product’s identity or source or both.

Substandard: A substandard drug is one that fails to meet national specifications cited in an accepted pharmacopeia or in the manufacturer’s approved dossier.

Unregistered: An unregistered product lacks market authorization from the national regulatory authority. Though it may be of good quality, an unregistered product is illegal.

The committee agrees with the emerging consensus that falsified and substandard are the two main categories of poor-quality drugs (Bate, 2012a; Clift, 2010; MSF, 2012; Newton, 2012; Oxfam International, 2011). The World Health Assembly (WHA) is the decision-making body of the WHO (WHO, 2013) and the international authority on questions of health policy. WHA endorsement of these two main categories would advance public discourse on the topic. The spirit of the definitions, not the exact wording suggested in Box 1-2, are key to this recommendation, as is the exclusion of the term counterfeit. Counterfeit is an overly broad term and should be used only to describe trademark infringement, which is not a problem of primary concern to public health organizations. As WHO Director-General Margaret Chan explained in the opening remarks of the November 2012 member state meeting on illegitimate drugs, “trade and intellectual property considerations are explicitly excluded” from the WHO’s discussions (Chan, 2012).

Falsified and substandard products are two useful categories in thinking about drug quality problems. There is overlap between these categories, but they are sufficiently precise for public discussion. Similarly, the problem of unregistered medicines is intimately linked to problems of drug quality.

The previous section mentions how national regulatory authorities set the quality standards for drugs. This section gives more detail on the history of modern medicine regulation.

National governments have long created officially recognized lists of legal drugs. Starting in the 16th and 17th centuries, city-based pharmacopeia attempted to standardize the apothecaries’ products (Brockbank, 1964). Modern pharmacopeias have been published since the 19th century: the U.S. Pharmacopeia in 1820 and the British Pharmacopoeia in 1864 (British Pharmacopoeia, 2012a; USP, 2012).

The strength of regulation by pharmacopeial standards depends on the regulatory agency to enforce the standards. In the United States, the Drug Import Act of 1848 made the U.S. Pharmacopeia the national drug compendium (USP, 2012). This recognition made the drug quality standards legally binding. In the latter half of the 19th century, state governments created licensing boards for pharmacists and pharmacies, and these boards emphasized the importance of the pharmacopeial standards (USP, 2012). The Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906 recognized the U.S. Pharmacopeia standards as official and to be enforced by the Bureau of Chemistry in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the forerunner of today’s FDA (Swann, 2009; USP, 2012).

Terra silligata, medicinal clay from the Greek island of Lemnos (left), was stamped with a seal of authenticity (right), an early example of a drug trademark.

SOURCE: Wellcome Library, London.

The passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in 1938 gave the FDA new authorities and recognized the quality, packaging, and labeling standards published in the pharmacopeia and the national formulary (USP, 2012). The act also gave the FDA inspectorate the authority to enforce these standards (USP, 2012). The 1960s saw several changes to accepted drug regulation, including the creation of an Adopted Names Council, an organization that establishes the United States Adopted Names, unique nonproprietary names for drugs (AMA, 2012; USP, 2012). Eventually the U.S. Pharmacopeia purchased the National Formulary and Drug Standards Laboratory from the American Pharmacists’ Association (USP, 2012). They merged the formulary and pharmacopeia in 1975, creating a collection of more than 4,000 monographs (USP, 2008).

Around the same time in Europe, the unified economic community was encouraging the use of regional pharmacopeial standards (EDQM, 2012). The first official European pharmacopeia was published in 1964 and is currently in its seventh edition (EDQM, 2012; European Pharmacopoeia, 2012). The European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines maintains and revises the European Pharmacopoeia and runs chemical and biological laboratories devoted to testing pharmaceutical products intended for the EU market (EDQM, 2012). While the FDA enforces pharmacopeial standards in the United States, both the national regulatory authorities and the European Directorate enforce the pharmacopeial standards in Europe (AVMA, 2012; EDQM, 2012). The European Medicines Agency (EMA), often described as the counterpart of the FDA, is primarily a medicines registration (review and approval) agency. The European Directorate has more responsibility for enforcing quality standards (EDQM, 2012).

In China and India, national pharmacopeial standards and organizations have developed rapidly in the last two decades. The government of India began enforcing pharmaceutical standards more systematically after the Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1940 (Gothoskar, 1983). Only in 2009, however, did the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission became an independent agency under the Ministry of Health, separate from the drug regulatory authority (Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2011). The Indian government also maintains a pharmacopeia on ayurvedic medicines, first published in a single volume in 1978 (Pharmacopoeial Laboratory for Indian Medicine, 2011).

Registration Agencies and National Pharmaceutical Authorities

National regulatory authorities are responsible for approving new drugs, also known as drug registration or medicines licensing (Rägo and Santoso, 2008). These agencies conduct the premarket safety and efficacy

reviews. They also conduct inspections and enforce quality control regulations.

The USDA Bureau of Chemistry was the forerunner of the FDA and one of the first agencies dedicated to quality enforcement for food and drugs (FDA, 2010). This agency enforced drug quality and antiadulteration standards in accordance with the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906. In 1927 it became a separate agency in the Department of Agriculture (Swann, 2009). Premarket review for drugs was not part of the drug registration process in the United States until the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, though premarket authorization of vaccines was mandatory after 1902 (FDA, 2012c).

The development of national registration entered a new phase in the two decades following World War II. In the 1940s and 1950s, before the thalidomide crisis of the early 1960s, federal drug regulators in the United States began to regulate efficacy (Carpenter, 2010; FDA, 2012c). In 1958, the Netherlands Medicines Act created an advanced administrative drug registration system and established, but did not yet use, the Medicines Evaluation Board to regulate market approval of new drugs (Carpenter, 2010; MSH, 2012).

The global thalidomide tragedy in the early 1960s changed all these institutions. Thalidomide was a sedative and antiemetic developed in Germany, used widely throughout Australia, Europe, and Japan in the late 1950s (Kim and Scialli, 2011). It was effective against morning sickness and commonly prescribed to pregnant women (Bren, 2001; Kim and Scialli, 2011). By 1961, however, thalidomide was identified as the cause of severe birth defects in more than 10,000 children. Birth defects included abnormally short limbs, toes sprouting directly from the hips, flipper-like arms, or no limbs at all; eye and ear defects; and congenital heart disease (Bren, 2001; Kim and Scialli, 2011). The drug was pulled from the market in 1961 and 1962 (Fintel et al., 2009; Kim and Scialli, 2011). Thalidomide had been licensed in 46 countries, but in the United States, the FDA had refused to approve its application and the drug never entered the market (Bren, 2001).

After the tragedy, governments worldwide revamped their drug regulation systems. The Drug Amendments of 1962 officially added efficacy to safety as a basis for FDA regulation and as a necessity for marketing authorization in the United States and imposed clinical trial requirements on drug development (FDA, 2012b). Australia, Britain, and Germany changed their systems of drug regulation in 1963 and 1964 (Daermmrich, 2003; Rägo and Santoso, 2008; TGA, 2003). Following the European Economic Community resolutions in 1965 and the 1970s, Britain, France, Germany, and other European nations took further steps to build stronger, more scientific regulatory agencies based in part upon the FDA model (Carpenter, 2010; ECHAMP, 2012). Hence, although thalidomide was not a problem of

substandard or falsified drugs, the reforms in its wake profoundly affected drug registration and quality control around the world.

Good manufacturing practices and bioequivalence standards, in addition to traditional pharmacopeial standards, are two of the most important conceptual instruments of modern drug quality regulation. Good manufacturing practices issued from the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act’s stipulation that if “the methods used in, and the facilities and controls used for, the manufacture, processing, and packing of such [new] drugs are inadequate to preserve its identity, strength, quality and purity,” the FDA would reject the new drug application.6 After the 1941 sulfathiazole disaster, FDA officials strengthened inspection protocols, requiring manufacturers not simply to prove drug quality but to demonstrate and maintain practices that assured uniformly standard drugs as well. Good manufacturing practices have now been adopted worldwide and are used not only by national regulatory authorities but also by pharmacopeial organizations like the EDQM, international health organizations like the WHO, and the International Conference on Harmonisation. They are applied to traditional medicines as well as to allopathic drugs (Carpenter, 2010).

The rise of generic drugs in the 20th century raised new questions about bioequivalence. From the 1950s to the late 1970s, bioequivalence standards, which required measuring metabolites in urine and blood, replaced older standards of chemical equivalence, which required only laboratory and dissolution tests (Carpenter and Tobbell, 2011). Between 1973 and 1977, the FDA issued bioequivalence rules and, in 1979, published a book of therapeutically equivalent products. These rules, coupled with the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, cemented a new generic drug approval process and bioequivalence regulations (Carpenter and Tobbell, 2011).

______________________

6 The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. ![]() 355(d)(3)(2012).

355(d)(3)(2012).

TABLE 1-1 Definitions of Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals

|

Organization |

Definition |

|

|

WHO |

1992 |

“A counterfeit medicine is one which is deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled with respect to identity and/or source. Counterfeiting can apply to both branded and generic products and counterfeit products may include products with correct ingredients, wrong ingredients, without active ingredients, with insufficient quantity of active ingredient or with fake packaging” (WHO, 1992, p. 1). |

|

|

2003 |

“Counterfeit medicines are part of the broader phenomenon of substandard pharmaceuticals. The difference is that they are deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled with respect to identity and/or source. Counterfeiting can apply to both branded and generic products and counterfeit medicines may include products with the correct ingredients but fake packaging, with the wrong ingredients, without active ingredients or with insufficient active ingredients” (WHO, 2003a). |

|

|

2006 |

“Counterfeit medicines are part of the broader phenomenon of substandard pharmaceuticals…. They are deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled with respect to identity and/or source. Counterfeiting can apply to both branded and generic products and counterfeit medicines may include products with the correct ingredients but fake packaging, with the wrong ingredients, without active ingredients or with insufficient active ingredients” (WHO, 2006). |

|

|

2009 |

“A counterfeit medicine is one which is deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled with respect to identity and/or source. Counterfeiting can apply to both branded and generic products and counterfeit products may include products with the correct ingredients or with the wrong ingredients, without active ingredients, with insufficient active ingredients or with fake packaging” (WHO, 2009). |

|

|

2011 |

Never explicitly defined, except as part of the so-called spurious, substandard, falsified, falsely labeled, counterfeit (SFFC). “There are no good quality SSFC medicines. By definition SSFC medicines are products whose true identify and/or source are unknown or hidden. They are mislabeled … and produced by criminals” (WHO, 2011a). |

|

IMPACT |

2008 |

“The term counterfeit medical product describes a product with a false representation (a) of its identity (b) and/or source (c). This applies to the product, its container or other packaging or labeling information. Counterfeiting can apply to both branded and generic products. Counterfeits may include products with correct ingredients/components (d), with wrong ingredients/components, without active ingredients, with incorrect amounts of active ingredients, or with fake packaging. Violations or disputes concerning patents must not be confused with counterfeiting of medical products. Medical products (whether generic or branded) that are not authorized for marketing in a given country but authorized elsewhere are not considered counterfeit. Substandard batches of, or quality defects or non-compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices/Good Distribution Practices (GMPs/GDPs) in legitimate medical products must not be confused with counterfeiting. Notes: a) Counterfeiting is done fraudulently and deliberately. The criminal intent and/or careless behavior shall be considered during the legal procedures for the purposes of sanctions imposed. b) This includes any misleading statement with respect to name, composition, strength, or other elements. c) This includes any misleading statement with respect to manufacturer, country of manufacturing, country of origin, marketing authorization holder or steps of distribution. d) This refers to all components of a medical product” (IMPACT, 2008). |

|

Oxfam |

A medicine that infringes on a trademark (Brant and Malpani, 2011). |

|

|

World Trade Organization |

“Unauthorized representation of a registered trademark carried on goods identical or similar to goods for which the trademark is registered, with a view to deceiving the purchaser into believing that he/she is buying the original goods” (WTO, 2012). |

|

|

World Bank |

“Counterfeits are usually defined as drugs that are deliberately made as fake copies of the original branded or generic drugs, imitating design, colors and other visible features. In many cases they contain only filling materials without any active ingredients. Or they may contain insufficient or an excess of active ingredients, or active drug substances other than the ones specified in the label” (Siter, 2005). |

|

|

World Medical Association |

“Counterfeit medicines are drugs manufactured below established standards of safety, quality and efficacy and therefore create serious health risks, including death” (WMA, 2012). |

|

|

Organization |

Definition |

|

|

TRIPS Agreement |

“[Counterfeit trademark goods] shall mean any goods, including packaging, bearing without authorization a trademark which is identical to the trademark validly registered in respect of such goods, or which cannot be distinguished in its essential aspects from such a trademark, and which thereby infringes the rights of the owner of the trademark in question under the law of the country of importation” (WTO, 1994). |

|

|

Doctors Without Borders |

“Counterfeit medicines are products that are presented in such a way as to look like a legitimate product although they are not that product. In legal terms this is called trademark infringement. They are the result of deliberate criminal activity that has nothing to do with legitimate pharmaceutical producers—be it generic or brand producers” (MSF, 2009). |

|

|

Pharmaceutical Security Institute |

Counterfeit medicines are products deliberately and fraudulently produced and/or mislabeled with respect to identify and/or source to make it appear to be a genuine product. This applies to both branded and generic products. They can have more or less than the required amount of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) or have the correct amount of API, but manufactured in unsanitary, unsafe conditions. This definition can also be extended to genuine medicines. Genuine medicines can be placed in counterfeit packaging to extend its expiry date (PSI-Inc., 2012). |

|

|

The Partnership for Safe Medicines |

“Counterfeit drugs are fake medicines intentionally made by unknown manufacturers who hide their identity. These drugs do not meet established standards of quality. Counterfeit drugs deceive consumers by closely resembling the looks of a genuine drug. They are made without approval of the regulator, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Counterfeiters create fake versions of branded, generic and over-the-counter drugs. Counterfeit medicines have been found to be made missing key ingredients; too strong or too weak; with the wrong active ingredient; with dangerous contaminants; in unsanitary or unsterile conditions; using unsafe methods; and with improper labels” (PSM, 2012). |

|

|

International Pharmaceutical Federation |

“Counterfeiting in relation to medicinal products means the deliberate and fraudulent mislabeling with respect to the identity, composition and/or source of a finished medicinal product, or ingredient for the preparation of a medicinal product. Counterfeiting can apply to both branded and generic products and to traditional remedies. Counterfeit products may include products with the correct ingredients, wrong ingredients, without active ingredients, with insufficient quantity of active ingredient or with false or misleading packing; they may also contain different, or different quantities of, impurities both harmless and toxic” (FIP, 2003). |

|

|

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations |

“Counterfeit medicines threaten the full spectrum of legitimate medicines. They can be falsified versions of patented medicines, generic medicines or over-the-counter medicines and exist in all therapeutic areas (even traditional medicine). They range from medicines with no active ingredients to those with dangerous adulterations” (IFPMA, 2010). |

|

TABLE 1-2 National Definitions of Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals

|

Country |

Definition |

|

|

Cambodia |

“A counterfeit pharmaceutical product is a medicine: 1. which is deliberately produced with the incorrect quantity of active ingredients or wrong active ingredients, or 2. a medicine that is either without active ingredients, or with amounts of active ingredients that are deliberately outside the accepted standard as defined in standard pharmacopoeias, or 3. a medicine that is deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled with respect to identity and/or source, or one with fake packaging, or 4. a medicine that is repacked or produced by an unauthorized person” (Phana, 2007). |

|

|

United States |

Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act |

“A drug which, or the container or labeling of which, without authorization, bears the trademark, trade name, or other identifying mark, imprint, or device, or any likeness thereof, of a drug manufacturer, processor, packer, or distributor other than the person or persons who in fact manufactured, processed, packed, or distributed such drug and which thereby falsely purports or is represented to be the product of, or to have been packed or distributed by, such other drug manufacturer, processor, packer, or distributor.”a |

|

|

U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website |

“Counterfeit medicine is fake medicine. It may be contaminated or contain the wrong or no active ingredient. They could have the right active ingredient but at the wrong dose. Counterfeit drugs are illegal and may be harmful to your health” (FDA, 2012a). |

|

|

United States Code |

Having a spurious trademark, not genuine or authentic, identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from the genuine trademark, registered on the principal register in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in use. The counterfeit mark is likely to cause confusion, to cause mistakes, or to deceive. [general trademark counterfeit]b |

|

Country |

Definition |

|

|

China |

Drug Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China |

“A drug is a counterfeit drug in any of the following cases: 1. the ingredients in the drug are different from those specified by the national drug standards; or 2. a non-drug substance is simulated as a drug or one drug is simulated as another. A drug shall be treated as a counterfeit drug in any of the following cases: 1. its use is prohibited by the regulations of the drug regulatory department under the State Council; 2. it is produced or imported without approval, or marketed without being tested, as required by this Law; 3. it is deteriorated; 4. it is contaminated; 5. it is produced by using drug substances without approval number as required by this Law; or 6. the indications or functions indicated are beyond the specified scope.”c |

|

Philippines |

“Medicinal products with correct ingredients but not in the amounts as provided there under, wrong ingredients, without active ingredients, with insufficient quantity of active ingredients, which results in the reduction of the drug’s safety, efficacy, quality, strength, or purity. It is a drug which is deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled with respect to identity and/or source or with fake packaging and can apply to both branded and generic products. It shall also refer to: 1) the drug itself, or the container or labeling thereof or any part of such drug, container, or labeling bearing without authorization the trademark, trade name, or other identification mark or imprint or any likeness to that which is owned or registered in the Bureau of Patent, Trademark, and Technology transfer in the name of another natural or juridical person; 2) a drug product refilled in containers by unauthorized persons if the legitimate labels or marks are used; 3) an unregistered imported drug product, except drugs brought in the country for personal us as confirmed and justified by accompanying medical records; and 4) a drug which contains no amount of or a different active ingredient, or less than 80% of the active ingredient it purports to possess, as distinguished from an adulterated drug including reduction or loss of efficacy due to expiration” (Clift, 2010, p. 15). |

|

|

Pakistan |

“A drug, the label or outer packaging of which is an imitation of, resembles as to be calculated to deceive, the label or outer packing of a drug manufacturer” (Clift, 2010, p. 15). |

|

|

Nigeria |

“a) Any drug product which is not what it purports to be; or b) any drug or drug product which is so colored, coated, powdered or polished that the damage is concealed or which is made to appear to be better or of greater therapeutic value than it really is, which is not labeled in the prescribed manner or which label or container or anything accompanying the drug bears any statement, design, or device which makes a false claim for the drug which is false or misleading; or c) any drug or drug product whose container is so made, formed or filled as to be misleading; or d) any drug product whose label does not bear adequate directions for use and such adequate warning against use in those pathological conditions or by children where its use may be dangerous to health or against unsafe dosage or methods or duration of use; or e) any drug product which is not registered by the Agency in accordance with the provisions of the Food, Drugs and Products (Registration, etc.) Decree 1993, as amended” (Clift, 2010, p. 15). |

|

|

India |

Mashelkar Report |

“The term, ‘counterfeit’ that is commonly used worldwide for spurious drugs does not appear in Drugs and Cosmetic Act but the definition of spurious drug comprehensively covers counterfeit drugs. According to the Drugs and Cosmetic Act (by the Amendment Act of 1982, section 17-B) spurious drugs are: a) manufactured under a name which belongs to another drug; or b) an intimation of, or a substitute for, another drug or resembles another drug in a manner likely to deceive or bear upon it or upon its label or container the name of another drug unless it is plainly and conspicuously marked so as to reveal its true character and its lack of identity with such other drug; or c) labeled or in a container bearing the name of an individual or company purporting to be the manufacturer of the drug, which individual or company is fictitious or does not exist; or d) substituted wholly or in part by another drug or substance; or e) purporting to be the product of a manufacturer of whom it is not truly a product” (Government of India, 2003). |

|

Country |

Definition |

|

|

Indonesia |

2000 |

Per the Republic of Indonesia’s Ministry of Health (MOH) Regulation No. 242/2000, counterfeit medicine(s) is/are the medicine(s) that are produced by the party/parties who has/have no authority to produce it based on the government’s act. There are five kinds of counterfeit medicines: 1. Product containing API with required concentrations; produced, packaged, and labeled as the original product, but this product is produced by the party without license. 2. The medicine contains API, but the concentration is outside of requirements. 3. Product is made as the original form and package, but no content of API. 4. The product is similar to the original, but content is of different substances/materials. 5. Products that are produced without a permit from the MOH. Per Republic Indonesian MOH Regulation No. 949/MenKes/SK/VI/2000 imported product/s that are illegal can be grouped as counterfeit without a permit for circulation issued by the National Agency of Food and Drug Control. |

|

|

2008 |

Per the republic of Indonesia’s Regulation No. 1010/2008, counterfeit medicines are produced by the party/ies who has/have no authority to produce the medicines by the government’s act, or medicines whose identities are imitated by other medicines that already have a circulating permit. There are three categories of counterfeit medicine: 1. The volume of substance (API) and the trade name is the same as the original medicine, but produced by the party who has no license to produce it. 2. The trade name is the same as the original medicine, but the volume of substance (API) is different and produced by the other producer. 3. The trade name is the same as the original, but the content of substance (API) is not medicine and not clear how the processing produced the drug. |

|

Kenya |

2008 Anti-Counterfeit Bill |

“‘Counterfeiting’ means taking the following actions without the authority of the owner of any intellectual property right subsisting in Kenya or elsewhere in respect of protected goods— a) the manufacture, production, packaging, re-packaging, labeling or making, whether in Kenya or elsewhere, of any goods whereby those protected goods are imitated in such manner and to such a degree that those other goods are identical or substantially similar copies of the protected goods; b) the manufacture, production or making, whether in Kenya or elsewhere, the subject matter of that intellectual property, or a colorable imitation thereof so that the other goods are calculated to be confused with or to be taken as being the protected goods of the said owner or any goods manufactured, produced or made under his license; c) the manufacturing, producing or making of copies, in Kenya or elsewhere, in violation of an author’s rights or related rights.”d |

|

Mexico |

It is considered a falsificado product when it is manufactured, packaged, or sold with reference to an authorization that does not exist, or uses a permit granted by law to another or imitation of legally manufactured and registered products.e |

|

|

Europe |

Council of Europe |

A false representation as regards identity and/or source (Council of Europe, 2011). |

|

|

European Medicines Agency |

“Counterfeit medicines are medicines that do not comply with intellectual-property rights or that infringe trademark law” (EMA, 2012). |

|

Vietnam |

“Counterfeit drugs mean products manufactured in any form of drug with a deceitful intention, and falling into one of the following cases: a) they have no pharmaceutical ingredients; b) they have pharmaceutical ingredients, which are, however, not at registered contents; c) they have pharmaceutical ingredients different from those listed in their labels; d) they imitate names and industrial designs of drugs which have been registered for industrial property protection of other manufacturing establishments.”f |

|

a Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. As amended December 19, 2002. Chap. II, Sec. 201, (g)(2).

b 18 U.S.C. § 2320.(f)(1). (2012).

c Drug Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China.(China). 2001. Chap. V, Art. 48.

d The Anti-Counterfeit Bill, 2008. (Kenya). PartI, 2(a-c).

e Ley General de Salud. (Mexico). 2013. Tit. 1, Chap. 1, Art. 208 bis.

f Law on Pharmacy. (Vietnam). 2005. Chap. 1, Art. 2. (24).

TABLE 1-3 Definitions of Substandard Pharmaceuticals

|

Organization |

Definition |

|

|

|

World Health Organization |

2003 |

“Substandard medicines are products whose composition and ingredients do not meet the correct scientific specifications and which are consequently ineffective and often dangerous to the patient. Substandard products may occur as a result of negligence, human error, insufficient human and financial resources or counterfeiting” (WHO, 2003a). |

|

|

|

2006 |

“Substandard pharmaceuticals [are] medicines manufactured below established standards of safety, quality and efficacy” (WHO, 2006). |

|

|

|

2009 |

“Substandard medicines (also called out of specification [OOS] products) are genuine medicines produced by manufacturers authorized by the [national medicines regulatory authority] which do not meet quality specifications set for them by national standards” (WHO, 2009). |

|

|

|

2010 |

“Each pharmaceutical product that a manufacturer produces has to comply with quality standards and specifications at release and throughout the product shelf-life required by the territory of use. Normally, these standards and specifications are reviewed, assessed and approved by the applicable national medicines regulatory authority before the product is authorized for marketing. Substandard medicines are pharmaceutical products that do not meet their quality standards and specifications” (WHO, 2010). |

|

|

|

2011 |

Substandard medicines are pharmaceutical products that do not meet their quality standards and specifications. “They arise mostly due to the application of poor manufacturing practices by the producer or when a good quality medicine is stored and distributed under improper conditions leading to deterioration of the quality of the product” (WHO, 2011a). |

|

|

Oxfam |

“Substandard medicines do not meet the scientific specifications for the product as laid down in the WHO standards. They may contain the wrong type or concentration of active ingredient, or they may have deteriorated during distribution in the supply chain and thus become ineffective or dangerous” (Brant and Malpani, 2011). |

||

|

The Partnership for Safe Medicines |

“Substandard drugs are produced by a known manufacturer, but they do not meet the quality standards of the drug regulator. In the United States, these high standards are set by the United States Pharmacopeia and the National Formulary. There is no intent to fool or defraud the consumer. Substandard medications are a result of manufacturer that do not follow approved Good Manufacturing Practices, which is regulated by the FDA. Simply stated, these drugs fall below the established standard—hence the term ‘substandard drugs’” (PSM, 2012). |

||

|

U.S. Pharmacopeia |

“Substandard drugs can be found in a variety of forms. A substandard product is a legally branded or generic product, but one that does not meet international standards for quality, purity, strength, or packaging. To be considered ‘substandard’ a product could: • Contain no active ingredient, but harmless inactives; • Contain harmful or poisonous substances; • Not be registered, or have been manufactured clandestinely, or smuggled into the country and thus be on sale illegally; • Have been registered inadvisably by a weak agency; or • Have passed its expiration date” (Smine, 2002, p. 1). |

|

|

World Bank |

“Substandard drugs are manufactured with the intent of making a genuine pharmaceutical product, but the manufacturer saves costs by not following GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) or using poor quality raw materials. Another potential problem relates to inadequate storage or transport conditions, leading to deterioration of the product. The performance of such medicines is questionable” (Siter, 2005). |

|

|

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations |

“All substandards are not counterfeits. A medicine which is approved and legally manufactured but does not meet all quality criteria is substandard, and may pose a significant health risk, but should not be regarded as counterfeit. However, all counterfeits are, by their nature, at high risk of being substandard” (IFPMA, 2010). |

|

TABLE 1-4 National Definitions of Substandard Pharmaceuticals

|

Country |

Definition |

|

|

Cambodia |

A substandard drug is a registered product, whose specifications are outside of accepted standards as defined by reference pharmacopoeias (Phana, 2007). |

|

|

China |

“A drug with content not up to the national drug standards is a substandard drug. A drug shall be treated as a substandard drug in any of the following cases: 1. the date of expiry is not indicated or is altered; 2. the batch number is not indicated or is altered; 3. it is beyond the date of expiry; 4. no approval is obtained for the immediate packaging material or container; 5. colorants, preservatives, spices, flavorings or other excipients are added without authorization; or 6. other cases where the drug standard are not conformed.”a |

|

|

Philippines |

“Substandard product means the product fails to comply, with an applicable risk of injury to the public.”b |

|

|

Thailand |

Substandard drugs are: “1. Drugs produced with active substances which quantity or strength are lower than the minimum or higher than the maximum standards prescribed in the registered formula to a degree less than the stated in Section 73 (5) [of the Thai Drug Act of 1967]. 2. Drugs produced so that their purity or other characteristics which are important to their quality differ from the standards prescribed in the registered formula under Section 79 or drug formulas which the Minister has ordered the drug formula registry under Section 86 bis [of the Thai Drug Act of 1967].”c |

|

a Drug Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China. (China). 2001. Chap. V, Art. 49.

b Republic Act No. 7394, The Consumer Act of the Philippines. (Philippines). Tit. I, Art. 4 (bt).

c Thailand Drug Act, B.E. 2510 (1967). (Thailand). Chap. VIII, Sec. 74.

TABLE 1-5 Other Terms of Interest

|

Organization |

Term |

Definition |

|

Oxfam |

Falsified |

Medicines for which the identity, source, or history was misrepresented (parent category for fake and falsely labeled) (Brant and Malpani, 2011). |

|

|

Falsely labeled |

The true properties of the product do not correspond to the information provided (Brant and Malpani, 2011). |

|

|

Fake |

Does not contain the correct type of concentration of active and/or other ingredients (Brant and Malpani, 2011). |

|

European Medicines Agency |

Falsified |

“Falsified medicines are fake medicines that pass themselves off as real, authorized medicines. Falsified medicines may: • contain ingredients of low quality or in the wrong doses; • be deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled with respect to their identity or source; • have fake packaging, the wrong ingredients, or low levels of the active ingredients. Falsified medicines do not pass through the usual evaluation of quality, safety and efficacy, which is required for the European Union (EU) authorization procedure. Because of this, they can be a health threat” (EMA, 2012). |

|

Brazil |

Falsification of medicines |

“Illicit reproduction of registered medicine, made by [a] third [party], with the fraudulent intention of giving a legitimate appearance of what is not legitimate” (Anvisa, 2006). |

|

|

Adulteration |

“Intervention of [a] third [party], with the purpose of altering legitimate medicine in [a] way to commit therapeutic effectiveness and/or to turn it noxious to the health; or intervention that modifies the specifications of the registration fraudulently, changing its registered formulation” (Anvisa, 2006). |

|

|

Alteration |

“Modification for addition or subtraction of components of the medicine and/or if the pharmaceutical formula, without previous and expressed approval of the National Agency of Health Surveillance” (Anvisa, 2006). |

|

Organization |

Term |

Definition |

|

Council of the European Union |

Falsified |

“Falsified medicinal product [is] any medicinal product with a false representation of: a) its identity, including its packaging and labeling, its name or its composition as regards any of the ingredients including excipients and the strength of those ingredients; b) its source, including its manufacturer, its country of manufacturing, its country of origin or its marketing authorization holder; or c) its history, including the records and documents relating to the distribution channels used. This definition does not include unintentional quality defects and is without prejudice to infringements of intellectual property rights.”a |

|

Thailand |

Deteriorated Drugs |

The following are deteriorated drugs: “1. A drug the expiry date of which as shown on the label has been reached. 2. A drug which has so denatured as to have the characteristics of a fake drug.”b |

|

|

Fake |

The following drugs or substances are fake drugs: “1. A drug or substance which is wholly or partly an imitation of a genuine drug; 2. A drug which shows the name of another drug, or an expiry date which is false; 3. A drug which shows a name or mark of a producer, or the location of the producer [of] the drug, which is false; 4. Drugs which falsely show that they are in accordance with a formula which has been registered; and 5. Drugs produced with active substances which quantity or strength [is] lower than the minimum or higher than the maximum standards prescribed in the registered formula by more than twenty percent.”c |

|

India |

Misbranded |

“A drug shall be deemed to be misbranded— a) if it is so colored, coated, powdered or polished that damage is concealed or if it is made to appear of better or greater therapeutic value than it really is; or b) if it is not labeled in the prescribed manner; or c) if its label or container or anything accompanying the drug bears any statement, design or device which makes any false claim for the drug or which is false or misleading in any particular.”d |

|

|

Adulterated |

“A drug shall be deemed to be adulterated— a) if it consists, in whole or in part, of any filthy, putrid or decomposed substance; or b) if it has been prepared, packed or stored under insanitary conditions whereby it may have been contaminated with filth or whereby it may have been rendered injurious to health; or c) if its container is composed in whole or in part, of any poisonous or deleterious substance which may render the contents injurious to health; or d) if it bears or contains, for purposes of coloring only, a color other than one which is prescribed; or e) if it contains any harmful or toxic substance which may render it injurious to health; or f) if any substance has been mixed therewith so as to reduce its quality or strength.”e |

a Directive 2011/62/EU on the community code relating to medicinal products for human use, as regards the prevention of the entry into the legal supply chain of falsified medicinal products [2011] OJ L174/77-78.

b Thailand Drug Act, B.E. 2510 (1967). (Thailand). Chap. VII, Sec. 75.

c Thailand Drug Act, B.E. 2510 (1967). (Thailand). Chap. VII, Sec. 73.

d The Drugs and Cosmetics Act and Rules. (India). As corrected up to 30th April, 2003. Chap. III, 9C.

e The Drugs and Cosmetics Act and Rules. (India). As corrected up to 30th April, 2003. Chap. III, 9A.

AFI (American Film Institute). 2003. AFI’s 100 years … 100 heroes & villains. http://www.afi.com/100years/handv.aspx (accessed November 7, 2012).

AMA (American Medical Association). 2012. About us. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-science/united-states-adopted-names-council/about-us.page? (accessed November 16, 2012).

American Heritage Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. 2012a. “Drug.” Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

———. 2012b. “Medicine.” Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

———. 2012c. “Pharmaceutical.” Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Amin, A., and R. Snow. 2005. Brands, costs and registration status of antimalarial drugs in the Kenyan retail sector. Malaria Journal 4(36). DOI: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-36.

Anvisa. 2006. The Anvisa effort on combating counterfeit medicines in Brazil. Paper presented at World Congress of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2006: 66th International Congress of FIP, Salvador Bahia, Brazil.

Attaran, A., D. Barry, S. Basheer, R. Bate, D. Benton, J. Chauvin, L. Garrett, I. Kickbusch, J. C. Kohler, K. Midha, P. N. Newton, S. Nishtar, P. Orhii, and M. McKee. 2012. How to achieve international action on falsified and substandard medicines. British Medical Journal 345. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.e7381.

Attaran, A., and R. Bate. 2010. A counterfeit drug treaty: Great idea, wrong implementation. Lancet 376(July):1446-1448.