Advancing Molecular Diagnostics for Oncology

Important Points Emphasized by Individual Speakers

- A critical step to improve the generation of evidence for molecular diagnostics in oncology is to determine what unmet medical needs require prospective randomized trials to develop the evidence base.

- Other critical steps are to develop informative assays for use in research and practice and to overcome the segmentation within the provider community, including the divide between the medical benefit and the pharmacy benefit.

- The totality of evidence from interventional studies, observational studies, registries, and other sources needs to be combined to produce better outcomes for patients.

The final session of the workshop focused on pathways that could address both the opportunities and the challenges associated with the development of molecular diagnostics for oncology. Each of the five speakers emphasized that partnerships are an especially valuable way to accelerate evidence development. The availability of specimens and good quality clinical data, to name just one example, inevitably requires collaborative efforts among stakeholders. Also, collaborations are essential to overcome barriers imposed by costs, limited numbers of patients, and regulatory requirements.

Several speakers cited examples of successful collaborations, and all pointed toward the steps needed to replicate and extend such successes.

BIOMARKER STUDIES IN MULTICENTER CANCER CLINICAL TRIALS: THE ROLE OF COOPERATI VE GROUPS

As chair of the NCI-funded Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) for 15 years, Richard Schilsky, professor of medicine and chief of the Section of Hematology and Oncology at the University of Chicago, has had many experiences involving the kinds of partnerships that will be essential to accelerate the development and use of molecular diagnostics in oncology. He has participated in exploratory studies using clinically annotated biospecimens and research assays (commonly called correlative studies), prospective-retrospective studies using clinically annotated specimens with known clinical outcomes and using either research or analytically validated assays, prospective biomarker-drug codevelopment studies, prospective biomarker development studies, and prospective biomarker validation studies.

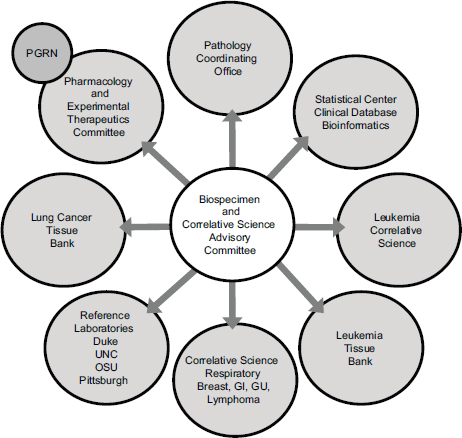

These studies require a large and expensive infrastructure, Schilsky said, and an advisory committee to help coordinate a range of activities involving many different disciplinary and interdisciplinary groups (see Figure 5-1). CALGB, like all of the NCI collaborative groups, has an NCIfunded biobank; it is located at The Ohio State University and is called the Pathology Coordinating Office. It also has a leukemia tissue bank that has collected frozen leukemia specimens and a lung cancer tissue bank that has collected frozen lung cancer specimens. All of the specimens, with the exception of those in the lung cancer bank, have been collected only from patients enrolled in clinical trials. “They were generally high-quality specimens collected in a uniform way from patients who met the eligibility criteria to participate in the study and for whom the outcomes were known,” Schilsky said. In addition, CALGB established a number of reference laboratories that had specific analytical expertise. Finally, he pointed out that a collaboration with the Pharmacogenomics Research Network led to germline genotyping studies that were implemented in the group, which led to a collaboration with the Riken Institute in Japan that did much of the genotyping.

Examples of Biomarker Development

As examples of projects enabled by CALGB, Schilsky cited several exploratory biomarker studies. In an adjuvant chemotherapy study done in patients with node-positive colon cancer, treatment with irinotecan did not add any benefits to the previous standard of care (Saltz et al., 2007).

FIGURE 5-1 Many kinds of organizations interact in the translational science infrastructure.

NOTE: GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; OSU, The Ohio State University; PGRN, pharmacogenomics research network; UNC, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

SOURCE: Richard Schilsky, workshop presentation, May 24, 2012.

Primary tumors were collected from all 1,200 patients enrolled in the study, which afforded the ability to look at a variety of biomarkers rather than a treatment effect. This work found, for example, that KRAS mutation is not prognostic in stage III colon cancer, but BRAF mutation is prognostic of survival. A hypothesis emerging from the study is that irinotecan might be beneficial in patients with BRAF mutations, but that hypothesis needs further testing.

A breast cancer study done in the 1990s established that Taxol is a useful component of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with node-positive breast cancer (Henderson et al., 2003). Yet, as in many adjuvant studies,

the incremental benefit of Taxol is relatively small when examined over the entire trial population. Subsequent study of the tumors from trial participants revealed that the benefits were limited to women who had ER-negative and/or HER2-positive breast cancer (Hayes et al., 2007), thus targeting the therapeutic to those who will benefit while relieving those who would not benefit of deleterious side effects. The remaining biospecimens from this study are being used now to develop a taxane-sensitivity signature.

A randomized Phase II study of the drugs zileuton and celecoxib in non-small-cell lung cancer found that they did not produce better outcomes than standard chemotherapy (Edelman et al., 2008). But subsequent analysis of the biospecimens from the study participants suggested that celecoxib use in patients whose tumors express high levels of COX-2 might be beneficial. An ongoing prospective RCT is testing whether the use of celecoxib in this biomarker-selected population will produce a survival benefit.

As an example of biomarker-drug codevelopment, Schilsky cited a placebo-controlled, prospective randomized trial for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in which FLT3 is expressed at high levels to examine standard chemotherapy with the addition of a FLT3 inhibitor. This study was done in collaboration with Novartis and would have been impossible to do without the company, said Schilsky, because Novartis supplied the drug and had access to sufficient numbers of patients with the mutation to do the study. The study was done on three continents, Europe, North America, and South America, and involved eight reference laboratories in different regions of the world, all of which used the same reagents and procedures. Although the results from the trial were not available at the time of the workshop, the study is a good example of the strategies that may need to be used when doing assay-drug codevelopment.

As an example of a prospective-retrospective study, Schilsky described the use of specimens from a negative clinical trial of a monoclonal antibody therapy in early stage non-small-cell lung cancer to provide a validation of the Oncotype DX colon cancer test (O’Connell et al., 2010). The results, which were presented at an American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting, mirror the results developed by Genomic Health using other datasets.

With regard to prospective marker validation studies, Schilsky mentioned a “perfectly designed biomarker study that fell flat on its face.” A collaboration among several cooperative groups sought to validate the utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) testing to select patients to receive erlotinib as part of their therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. The study was designed collaboratively with NCI and “essentially met the gold standard for the way a biomarker validation study would be designed,” according to Schilsky. By the time the study got under way, however, the

lung cancer community had lost interest in the clinical question posed by the study.

Finally, Schilsky mentioned the TAILORx (Trial Assigning IndividuaLized Options for Treatment (Rx)) study, which was a collaborative effort across cooperative groups to validate the Oncotype DX test in breast cancer as a test that can be used to allow patients with an intermediate risk score to safely forgo receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. The study has completed accrual but does not have results yet.

General Observations

Cooperative groups have the capacity to conduct many types of biomarker studies, including formal validation trials, said Schilsky, but there are many challenges such collaborative efforts must overcome, such as the following:

- The adequacy of the biospecimen collection.

- Access to CLIA-certified laboratories that can conduct analytically validated assays in a reproducible way.

- Funding for biomarker studies, especially for large prospective studies.

- Regulatory requirements.

- Contractual agreements with commercial partners.

For some questions, according to Schilsky, stakeholders need to be willing to accept that less-than-gold-standard RCTs may need to serve as sufficient evidence to make regulatory, payment, and clinical decisions. Large clinical trials are not always necessary or possible because not enough resources, patients, time, and investigators are available to answer every question. Therefore, the most important step to improve the generation of evidence for molecular diagnostics in oncology, according to Schilsky, is to determine what unmet medical needs require prospective randomized trials to develop the evidence base.

Schilsky also noted, as did other people at the workshop, that most adult patients with cancer are not part of clinical trials. The primary determinant of whether a patient enrolls in a clinical trial is whether a physician recommends doing so. But in the United States, there are almost no incentives for physicians to recommend that patients participate in a trial, and there are many disincentives. Instead, physicians are likely to prescribe a drug off label. Countries that do not tolerate off-label prescribing are much more successful than the United States in enrolling patients in clinical trials. An interesting idea Schilsky mentioned is that of the “cancer information donor,” where someone with a cancer diagnosis could volunteer to provide

information for cancer research even if that person is not participating in a clinical trial.

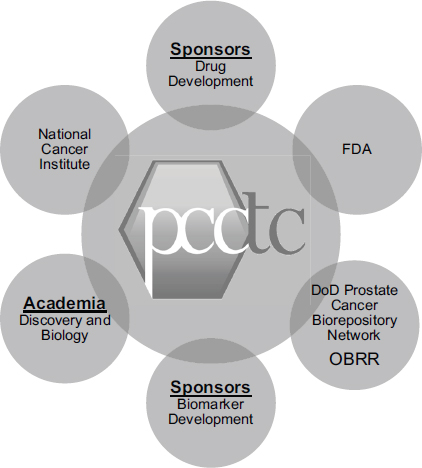

As an example of an especially effective collaboration, Howard Scher, the D. Wayne Calloway Chair in Urologic Oncology and chief of the Genitourinary Oncology Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, described the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium (PCCTC). It, too, has brought together a number of partners, with funding in part from the Department of Defense, to build the infrastructure to collaborate (see Figure 5-2). The mission of the collaboration is to design, implement, and complete hypothesis-driven Phase I and II trials of novel agents and combinations that could prolong the lives of patients with prostate cancer.1 The 13 cancer centers involved in the collaboration each have scientific programs to support biomarker discovery and a translational clinical research enterprise.

The guiding principles of the collaboration are that centrally managed, harmonized, and comprehensive clinical trial processes will accelerate drug development and improve outcomes. This goal can be achieved by streamlining any process that can impede trial activation, conduct, completion, and analysis, Scher said.

A framework to conduct clinical trials was developed by consensus within the groups in order to synchronize clinical research with clinical practice (Scher et al., 2008). “The same way that a drug is focused on an indication,” said Scher, “we’re focusing on the context of use.” Aligned to member-prescribed scientific priorities, teams of experts design trials in a sequence, each with “go–no go” metrics. Embedded in the collaboration is an extensive effort to discover and validate biomarkers analytically and clinically.

Since 2005, the PCCTC has submitted 152 letters of intent, with 118

______________

1 As of January 1, 2010, a reported 2,617,682 individuals were living with a prostate cancer diagnosis; 241,740 new cases and 28,170 deaths were reported in 2012 with an overall incidence of 152 per 100,000 men. Higher incidences have been found in African Americans than whites (228.5 versus 144.9 per 100,000 men) (ACS, 2012; Howlader et al., 2013). Digital rectal examination and prostate serum antigen (PSA) testing have been used for detection, though the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recently recommended against use of PSA-based screening (USPSTF, 2012). Treatment options include active surveillance, surgery, external beam radiation, brachytherapy, hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination approach depending on disease advancement. Sipuleucel-T or Abiraterone may also be employed in cases where tumors are no longer responsive to traditional therapy (ACS, 2012).

FIGURE 5-2 The Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium collaborates with critical stakeholders in drug and biomarker development.

NOTE: DoD, U.S. Department of Defense; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; OBRR, FDA Office of Blood Research and Review; PCCTC, Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium.

SOURCE: Howard Scher, workshop presentation, May 24, 2012.

protocols approved for activation. More than 3,200 men have been enrolled in Phase I and Phase II trials, and 8 therapeutic candidates have advanced to Phase III study.

Changing the Clinical Research Enterprise

In its first 6 years, the PCCTC has moved beyond its original charter in ways that have changed the clinical research enterprise, according to Scher. To illustrate this point, he focused on two new androgen axis inhibitors,

abiraterone and Medivation 3100. The development of these drugs was a great success, but that success also had a downside. Future trials would be more difficult because studies, in particular placebo-controlled studies, would need to be larger and longer; they would also be more costly because crossover to an effective treatment can confound a survival effect.

As a result, qualified surrogate biomarkers for survival are urgently needed that can be used for accelerated drug approvals. Also needed are qualified predictive biomarkers of sensitivity to better match drugs to an individual patient’s tumor. “The era of ‘all comers’ trials will soon be ending,” said Scher.

Both abiraterone and Medivation 3100 were studied in pre- and postchemotherapy castration-resistant prostate cancer. Circulating tumor cell numbers were included as an end point, though before this could be used as a biomarker, the platform used to do the assay had to undergo analytical testing. This testing was designed to establish the minimum performance characteristics to justify the use of the assay in clinical testing and to achieve analytical validity across laboratories. Analysis of the first Phase III registration trial has led to positive results, Scher reported, “so we’re in a very good position to look at both circulating tumor cells and other markers for their potential impact on survival.” The development process led to FDA approval of abiraterone and submission of a New Drug Application for Medivation 3100 the same week as the workshop. Throughout this process, interactions with FDA “have been extremely favorable and extremely helpful,” said Scher.

A rate-limiting factor has been the availability of analytically valid assays, Scher said. The collaboration has been looking at various putative predictive markers for patients who respond to treatment, do not respond to treatment, and develop resistance after treatment. Several markers have been postulated, but none has warranted testing in a large-scale trial. Meanwhile, the collaboration has been storing specimens for future analysis and has been working to develop assays of biomarkers that it thinks will be included in future panels.

Implementation of a Precision Medicine Paradigm

With a Stand Up To Cancer award, members of the collaboration are now pursuing precision therapy for advanced prostate cancer. The objective is to establish a “Rosetta stone” resource of mutation profiles of advanced prostate cancer for researchers and patients. This effort will establish advanced prostate cancer as a model tumor type for the precision medicine paradigm and facilitate the use of clinical sequencing for cancer management, Scher said. Specific goals include the following:

- Establishing the use of precision tumor boards to help guide the management of advanced prostate cancer.

- Identifying resistance mechanisms and sensitivity biomarkers for new prostate cancer therapies.

- Identifying rare “actionable” mutations in advanced prostate cancer and providing rational clinical trial options to patients.

The key to success, said Scher, will be the availability of analytically valid assays when the trials are ready to begin. When hypotheses about the contributors to a cancer cannot be explored because of a lack of an effective assay, “it’s quite frustrating,” he said. “You know what you want to do, but you can’t.” At the same time, it is essential that the assays provide correct information. “If we are not confident of the diagnostic, then what we may do clinically may actually harm patients, which is what no one wants to do,” he added. Clinicians need to work closely with pathologists, he said, and pathologists need to be closely integrated into the development process.

Scher also said that less can be more with regard to data collection. Instead of trying to record everything, it may be better to capture the milestone events. “You want to get the key elements but not necessarily waste time on things that are not adding value to the patient, to the drug, or to the investigator,” he noted.

Scher also said that physicians are busy and that the demands on their time are increasing. Asking them to provide information on patients may be too difficult unless they get something in return. If they get data that improves practice, they will use and support a system. The system needs to serve the provider rather than having the provider serve the system.

PATIENT APPROACHES TO COLLABORATION

Patient advocacy has many dimensions, said President of Patient Advocates in Research Deborah Collyar, who spoke for a second time in the final session of the workshop. Patient advocates do fundraising, political advocacy, direct patient support, watchdog advocacy, and research advocacy. “Many of us have done all of those different things,” she said.

As a result, patient advocates tend to be involved in many different types of networks and partnerships, including networks of advocates. For example, patient advocates have been extensively involved in the cooperative groups described by Schilsky. As part of this work, they have helped to develop and design research concepts, protocols, consent forms, and results summaries. They also have been represented in advisory groups for biospecimen collections and correlative studies and have helped develop standards for consent processes.

Patients also have worked closely with translational research programs

such as the Specialized Programs of Research Excellence. For example, they have been involved in the process of tissue collection and tissue awareness programs within the different communities. In addition, they conduct grant reviews and serve on advisory boards for companies and government agencies, Collyar said.

Patient advocates work with such groups as the Army of Women, which gathers information from survivors and from women who do not have breast cancer to find out more about research. If patients could play a more active role during their cancer experience, they would be more willing to contribute biospecimens and clinical data, Collyar said. Studies have shown that patient-reported outcomes are accurate, and such data could be used in multiple ways. Patient advocates also get involved in specific issues, such as the reproducibility of studies, which is “integral to how good information is once it goes to people,” she noted. In turn, that involvement produces opportunities to work with institutions to change policies and resolve barriers.

NOVEL PARTNERSHIP STRATEGIES TO DEVELOP EVIDENCE OF CLINICAL UTILITY

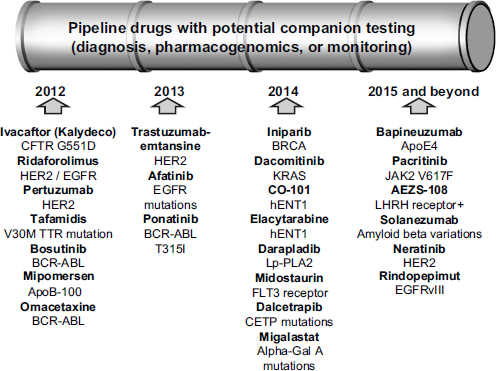

As Gabriela Lavezzari, director of development and diagnostics at Express Scripts, observed, the drug development pipeline is full of therapies accompanied by biomarkers (see Figure 5-3). But “the stars are not aligned,” Lavezzari said, regarding what different stakeholders want from those drug-diagnostic combinations. The payers want to lower costs, offer safer and more effective treatments, and have consistent management across benefits. Patients want better health outcomes, fewer health and safety issues, and lower out-of-pocket expenses for medications. Physicians want the current buy-and-bill system to remain, the administrative burden to be reduced, and clinical information to be improved.

“Everyone is working in silos,” said Lavezzari. “The patient has his own issues, trying to face a new disease and a new treatment. The physician is trying to find what the best treatment is for patients. The payer is trying to manage the cost of all these drugs… . In the end, everybody is frustrated.”

Barriers and Opportunities for Diagnostic Companies

Lavezzari also stated that diagnostic companies face many barriers, including incomplete disease knowledge, lack of market education (which depends on a strong understanding of clinical utility), market segmentation, little intellectual property protection, an uncertain regulatory environment, and no guarantee of reimbursement. In particular, diagnostic companies

FIGURE 5-3 Many drugs with potential companion tests are in the development pipeline.

NOTE: APO, apolipoprotein; BCR-ABL, breakpoint cluster region-abelson; BRCA, breast cancer susceptibility gene; CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FLT3, fms-related tyrosine kinase 3; Gal, galactosidase; hENT1, human solute carrier family 29 (nucleoside transporters), member 1; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; KRAS, v-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; LHRH, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone; Lp-PLA2, lipoprotein-associated phospholipid A2; TTR, transthyretin. SOURCE: Gabriela Lavezzari, workshop presentation, May 24, 2012.

struggle with payers’ questions about whether a diagnostic test is clinically useful and cost-effective. Payers ask: How well does the test perform? Do the test results change subsequent care? Does the change in care lead to better outcomes? What is the impact on overall cost?

Lavezzari has been working with diagnostics companies to help them understand and answer each of these questions. In the process, she has helped create different business models to help diagnostics companies advance their products. The offerings are integrated, extending from preto postproduct launch. For example, Lavezzari helps diagnostics companies

educate physicians and patients about new tests, create biobanks, and prove clinical utility.

Stakeholders look at approvals in different ways, Lavezzari noted. Off-label use of drugs is a good example of this dichotomy. Pharmacy benefit management companies follow FDA approvals for drug prescriptions, whereas guidelines groups can vary from this approved use on the basis of their reviews of agent-cancer combinations. Off-label prescriptions can be blocked from being dispensed because of this difference, leaving the patient stuck in the middle between the medical benefit and the pharmacy benefit. Pharmaceutical companies also need to be a part of the discussion on this issue, she said.

Lavezzari said that the most important step to improve the generation of evidence for molecular diagnostics in oncology would be to overcome the segmentation within the community, particularly between the medical and pharmacy benefit. “We cannot work on our own. The payer, the physician, and the patient that ultimately has to take the medication all have to work together.”

ASSESSING CLINICAL UTILITY WITH REAL-WORLD EVIDENCE

Major changes in the development of drugs and companion diagnostics have been forcing pharmaceutical companies to adopt new models, said Greg Rossi, vice president, Payer and Real World Evidence, at AstraZeneca UK. Information about disease is rapidly increasing, providing more potential therapeutic targets and identification of biomarkers. At the same time, however, the costs of development are growing rapidly, as are the evidentiary hurdles to be overcome. These barriers are causing many oncology drugs to be looked at as marginal candidates for development because the population sizes tend to be low, the risks associated with development high, and the evidentiary standards demanding. Inevitably, companies wonder in these circumstances about the security of their returns on investment, Rossi said. “We absolutely believe … in evidence-based medicine,” said Rossi. “But there is an opportunity cost associated with that evidence development.”

Today, about 15 companion diagnostics have been approved for 7 drugs. Since 2000, the total value of the market for such drugs has risen from about $3 billion to around $18 billion, Rossi said. This market has become highly valuable, but it is also a difficult one in which to operate. As diseases are divided into subgroups, smaller and smaller populations fall into those categories, and the costs of evidence generation go up, resulting in price increases for many of the agents. “The affordability of health care is really important as we think about the cost of development and the return on investment,” said Rossi.

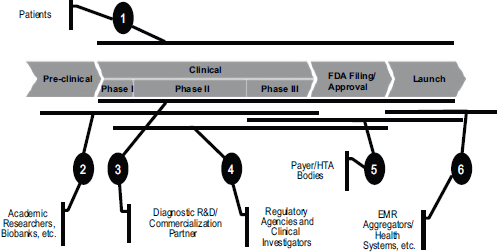

FIGURE 5-4 Partnerships are essential in developing companion diagnostics.

NOTE: EMR, electronic medical record; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HTA, health technology assessment; R&D, research and development.

SOURCE: Greg Rossi, workshop presentation, May 24, 2012.

Operating in this market requires multiple partnerships throughout the drug development process (see Figure 5-4). Patients are at the forefront, Rossi said. There is a contract with patients to make sure that the appropriately rigorous methodology and analysis are being performed in clinical trials to ensure that benefits are being maximized. There is also a need to team up at various stages with academic researchers, companies, regulatory agencies, payers, and health care systems in order to make sure that the right type of evidence is being generated. “We can’t do this without partnership,” he said.

Categorization of Companion Diagnostics

Woodcock (2010) divided personalized health care options into three categories. In true drug-diagnostic codevelopment, the clinical validity and utility have been demonstrated at the time of launch. With rescue diagnostics, retrospective or prospective analysis can be done to develop evidence to facilitate a label change. And with retrofit diagnostics, new information allows a drug already on the market to be used with a new or refined set of patients who can benefit from that drug.

This is a useful categorization, said Rossi, because it serves as a reminder that drug-diagnostic codevelopment is rarely a sequential and seamless process. For example, crizotinib started as a MET inhibitor before

the development program was refocused on patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer.2

He also briefly described differences among countries in assessments of clinical utility. In Italy, for example, all uses of high-cost oncology drugs go into a national registry so that practice patterns, clinical outcomes, and value can be assessed (Russo et al., 2010). “As we start thinking about real-world evidence, there are examples, in some countries and in many centers in this country, of innovative ways to think about how you collect data … to start answering the questions that we know are necessary and important,” he added.

Real-World Evidence

Real-world evidence is a somewhat amorphous term, Rossi admitted. He focused mostly on observational studies, splitting them into prospective observational studies and retrospective analyses.

The ACCE model process has defined clinical utility as “the balance of benefits and harms associated with the use of a test in practice, including improvement in relevant outcomes and the usefulness of added value in decision making compared with not using the test.”3 Observational studies should suffice to achieve this outcome, Rossi said, but in cancer, separating the clinical difference from the noise of the assay remains very difficult. Studies of electronic medical records and claims databases could be useful in determinations of clinical utility, but these are currently hampered by such challenges as a lack of integrated data on important patient clinical characteristics, a lack of pathologic and diagnostic data, and difficulty collating all associated direct and consequential costs.

Innovative assessments of real-world evidence have the potential to monitor practice patterns before and after the introduction of a technology, assess adherence to treatment guidelines, and monitor the total impacts on costs. They also can assess generalizability through comparisons of highlevel clinical outcomes with evidence from prior intervention trials. They can generate hypotheses about putative benefits and risks of competing strategies, and they can inform prospective registry designs and collaborations around those designs. “But we are going to struggle right now to get into some of the clinical data,” said Rossi, “and we are not going to be

______________

2 For a full discussion of the development of crizotinib and its companion Vysis ALK Break Apart FISH Probe test A, see IOM, 2012c.

3 The ACCE name is derived from the components of the model—analytic validity, clinical validity, clinical utility, and ethical, legal, and social implications. More information about the model is available at http://www.cdc.gov/genomics/gtesting/ACCE/FBR/index.htm (accessed August 13, 2012).

able to have comparative effectiveness types of questions [answered using] electronic medical records [EMRs] today.”

Rossi said that the most important step to improve the generation of evidence for molecular diagnostics in oncology would be to standardize clinical information, including data in EMRs, to provide information for the broader community. In this way, it would be possible to access much larger sample sizes, which will be particularly important with smaller subgroups of patients. Computerized natural language recognition could help extract valuable information from EMRs.

Rossi also said that informed consents for the tissues that are collected can produce limited degrees of freedom for how those samples are used. That is a key issue for the use of samples from biobanks, especially globally, since some standardization initiatives are under way in the United States.

The overarching challenge, said Rossi, is to use the totality of evidence from interventional studies, observational studies, registries, and other sources, rather than competing evidentiary approaches, to produce better outcomes for patients.

In concluding the meeting, Robert McCormack stated that the meeting helped clarify the hurdles that are preventing genomic tests from reaching patients. Stakeholders need to focus on defining when it is absolutely necessary to conduct RCTs and when other forms of evidence may be acceptable, he said. All the stakeholders have recognized their roles in the process and are trying to clarify what their needs are for demonstrating clinical utility. Speakers made a number of recommendations (see Box 5-1) that, if acted on, could spark much more progress. “It is going to take time and much more dialogue and partnership, but we have moved the ball down the field today,” McCormack said.

BOX 5-1

Proposals Made by Individual Speakers

This box compiles the suggestions made by individual speakers at the workshop to advance the development of measures of clinical utility for molecular diagnostics in oncology. These suggested actions should not be seen as recommendations of the workshop, but they are promising ideas for further discussion and possible implementation.

Definitions and Standards

- To demonstrate that clinical utility has been achieved, the concept of clinical utility needs to be better defined. (McCormack)

- To determine whether test results lead to changes in practice that can be linked to improved health outcomes, clear, predictable, and consistent standards of evidence need to be developed that can be used to judge diagnostic technologies. (Tunis)

- An evidentiary framework needs to articulate the minimal evidence necessary before the clinical application of a genomic technology is warranted. (Freedman)

- Well-defined measures of clinical utility need to be accepted, and then the magnitude of the impact on those measures needs to be set to justify the adoption of a test into guidelines or for regulatory approval. (Lyman)

- Focusing more on value than on cost-effectiveness in assessments of molecular diagnostics will enable analyses to be descriptive in addition to prescriptive and will allow consideration of the full context of care. (Phillips)

Evidence Generation

- A provisional period of several years during which payers cover part of the costs of a molecular diagnostic’s use would allow additional evidence to be gathered, after which the test could be accepted only if it produces substantial improvements in health outcomes. (Newcomer)

- For a biomarker to progress to a clear clinical test, it should have significant and independent value, be validated by clinical testing, be feasible and reproducible, and be widely available with quality control. (Benson)

- Test development needs to be rigorous, using meaningful and well-designed studies, proper statistical analysis, independent external validation, and interdisciplinary expertise. (McShane)

- Appropriate control groups are necessary to determine whether a marker is predictive and distinguishes a group that benefits from a treatment. (McShane)

- Studies of clinical utility should be conducted in settings that are relevant to more real-world clinical decisions. (Freedman)

- Clear priorities for comparative-effectiveness research could ensure that limited resources are used to resolve the most compelling questions. (Freedman)

- Unmet medical needs that require prospective randomized trials to develop their evidence bases need to be identified; this will also allow limited resources to be applied appropriately. (Schilsky)

- A clearinghouse of data on clinical utility from various sources could be used both in guidelines development and in deciding whether to cover or not cover the clinical use of a molecular diagnostic. (Leonard)

- A biomarker study registry could aid in identifying relevant biomarker studies for overviews and meta-analyses, make study protocols available, and help reduce nonpublication bias and selective reporting. (McShane)

- Creating an accelerated review and publication format specifically for personalized medicine assays could overcome the extended and biased review cycles in traditional publications. (Doheny)

- New strategies involving transformation of the research infrastructure to “learning systems” could allow continual additions to the knowledge base. (Freedman)

- An incentive structure for providers to put patients on clinical trials needs to be enabled. (Schilsky)

Sample and Data Collection

- Expanded access to well-annotated specimens, including alternative sources of specimens, would be especially useful for the development of molecular diagnostics. (McShane)

- The collection of blood and tissue from every patient with cancer, including patients who die, could greatly advance research. (Doheny)

- “Cancer information donors” could volunteer to provide information for cancer research even without participating in a clinical trial. (Schilsky)

- Standardization of clinical information, including data in electronic medical records, would be a valuable source of evidence for molecular diagnostics in oncology. (Rossi)

- A registry of patients with apparent false positives is needed in the development of measures of clinical utility. (Doheny)

- An integrated, outcomes-based database could be used to better understand external validity, inform unmet need assessments/trial designs, and identify variation in practice/hypotheses for detailed interventional studies. (Rossi)

Application in the Clinic

- The evidence generated and analyzed to demonstrate clinical utility needs to be adapted to the clinical setting. (McCormack)

- Clinical utility needs to receive earlier and more intense focus, with more education about how to interpret the results of tests. (McShane)

- FDA guidance should be applied to laboratory-developed tests. (Bast)

- Stakeholders need to be willing to accept that less-than-gold-standard randomized controlled trials may need to serve as sufficient evidence to make regulatory, payment, and clinical decisions. (Schilsky)

- Generation of evidence for molecular diagnostics in oncology would help overcome segmentation within the provider community, including the divide between the medical benefit and the pharmacy benefit. (Lavezzari)

- The totality of evidence from interventional studies, observational studies, registries, and other sources needs to be combined to produce better outcomes for patients. (Rossi)

- Observational/database analyses could be used to augment interventional study data to assist managed entry for new technologies. (Rossi)

The Patient’s Perspective

- The term “personalized medicine” should not be used because treatments can be targeted but not yet personalized to the individual level. (Collyar)

- A more relevant term than “clinical utility” for most patients is “personal utility” or “personal guidance.” (Collyar)

- Patients need to get test results quickly and in clear language, and test results need to be updated as the test or a person’s condition changes. (Collyar)

Partnerships

- Collaborations among cancer centers are essential, particularly to investigate rare cancers. (Freedman)

- A multitude of stakeholders having a role in evidence generation could lead to better studies. (Freedman)

- A major commitment of patients, insurers, government agencies, private institutions, and clinicians will be needed to foster partnerships aimed at innovation and technology development. (Benson)

- Modeling could be useful in determining evidence gaps and prioritizing efforts but will require consensus across stakeholders on what are considered reasonable assumptions. (Lyman)

- The sharing of emerging biomarker data can enrich research databases thereby informing the understanding of practice patterns and clinical outcomes in the real-world setting. (Rossi)