Understanding and Communicating Flood Risk Behind Levees

Inherent to the National Flood Insurance Program’s (NFIP’s) purpose of providing the opportunity for insurance purchase in flood-prone areas and the need to reduce flood damages across the nation is the need to develop public awareness of flood risk. Risk communication is the purposeful exchange of information about the types of risks and their likely impacts, and alternatives for managing the risks including benefits and costs. It is an iterative and interactive process involving a two-way mode of communication between sources and recipients of the information (Morgan et al., 2001). NRC (1989) defines risk communication as

an interactive process of exchange of information and opinion among individuals, groups, and institutions. It involves multiple messages about the nature of risk and other messages, not strictly about risk, that express concerns, opinions, or reactions to risk messages or to legal and institutional arrangements for risk management.

Risk communication includes both the risk information itself (messages) and sources of such information (messenger), as well as the channels (media) used in the delivery of the communication (e.g., mass media, social media, text messaging, face-to-face).

The goals of risk communication are to foster a communications environment based on trust and credibility, to provide sufficient information to an audience so that they can make informed decisions about risk-reducing behaviors, and to involve stakeholders in the decision-making process (NRC, 1989). Thus the risk communication process begins with the development of the risk management strategy including the identification of risk, its assessment, and the management of alternatives. Risk can be viewed very differently by sources and recipients. For example, the scientific community prefers to present information in an objective manner generally using statistical information and probabilities. The general public generally looks at risk information from a more subjective perspective and how it relates to their individual experience and self-benefit. In the latter case, perception and trust in and perceived credibility of the messenger are key determinants of the positive receptivity of the message (Fischhoff and Kadvany, 2011).

The challenges associated with communicating levee-related flood risk begin with challenges associated with the public perception of flood risk. Communicating the concept of residual risk behind a levee presents an additional challenge beyond the public perception of flood risk. The variety of levee-related stakeholders, including several federal agencies with different roles and responsibilities who are sources and recipients of

risk information, add additional complexity. So, rather than one entity confronted with the challenge of communicating risk to the public, levee-related flood risk communication efforts face the challenge of presenting a unified, effective communication among governments at all levels, as well as among agencies, the private sector, and the public.

Risk communication activities include both “regulatory” and “nonregulatory” communication products. Regulatory flood risk communication products are those centered on FEMA’s Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) and related documents (e.g., flood insurance studies), and nonregulatory products are all other FEMA products that communicate flood- and levee-related flood risk.

UNDERSTANDING FLOOD RISK PERCEPTION

Communication of flood risks to residents has a number of inherent challenges that affect stakeholders and begin with their perception of flood risk. Risk communication efforts can be enhanced by understanding risk perception.

First, people generally underestimate flood risk (Botzen et al., 2009; Kousky and Kunreuther, 2010; Kousky, 2011; Wood et al., 2012). This is due to misunderstanding about the frequency of flooding. Such underestimates are based on the tendency to recall or remember the most severe, or infrequent flood events, rather than the less severe but more frequent ones. It is also based on misunderstandings of the likely damages from various magnitudes of flooding.

Second, residents often misunderstand the term “100-year flood” and assume that if an event occurs, it will not happen for another 100 years (Pielke, 1999; Kousky and Kunreuther 2010; USGS, 2010; Ludy and Kondolf, 2012). The designation of the one percent annual chance flood is more effective in communicating uncertainty and is being promoted as such (Bell and Tobin, 2007; USGS, 2010). However, this does not necessarily translate into protective actions such as the adoption and/or implementation of risk reduction measures, as illustrated by low insurance penetration rates (Chapter 5).

Third, there is mixed empirical evidence to support the conclusion that increased risk perception translates into actions to reduce flood risk (e.g., mitigation) (Terpstra et al., 2009; Bubeck et al., 2012; Kellens et al., 2012; FEMA’s annual national surveys, mentioned later in this chapter). Although there is a positive association between risk perception and protective actions, it is more likely that other factors are more important, such as personal experience, personal attributes, and evaluations of the protective actions themselves.

Fourth, undertaking protective actions against flood risk, such as purchasing insurance and elevating homes, is more likely to be based on their efficacy and cost of implementation (Soane et al., 2010; Harvatt et al., 2011). Residents will evaluate the likely outcomes of protective actions according to varying levels of desirability, and if the outcome is viewed favorably and one that is desirable, it is more likely that a household or resident undertake that protective action (Grothmann and Reusswig, 2006; Bourque et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012; Lindell and Perry, 2012; Wood et al., 2012).

Fifth, there is considerable trust in flood control structures in preventing flood risks (Ludy and Kondolf, 2012). This is shown by lower insurance purchase rates in areas with levee protection compared with those without the same, for example, in the St. Louis region (Kousky, 2011). Tobin (1995) notes that levees can actually increase the potential for flood loss by generating a false sense of security, the “levee effect,” due to perception that the possibility of flooding has been eliminated, the lack of preparation for a flood event, and greater development behind the levee adding to the amount of property placed at risk. Thus, a fallacy that “levees prevent damages” occurs in society (Pielke, 1999), confounding the effective communication of residual risk in leveed areas.

Sixth, people will take the opinions and actions of friends, family, and neighbors into account in behavioral responses, a social exchange that is often termed milling or information seeking. In this regard, social networks are often more important than official sources of information about risks and mitigation options (Harvatt et al., 2011; Bourque et al., 2012).

Seventh, risk perception and behavioral responses are often influenced by experience with flooding. If there is little or no experience with flooding, then the negative effects of floods tend to be underestimated (Siegrist and Gutscher, 2008) and this provides less motivation to residents or households to engage in protective responses (Harvatt et al., 2011).

Eighth, risk communication tends to focus on the technical or material costs/benefits to trigger mitigation, yet recent research suggests that the emotional and experiential aspects of flooding provide more impetus for undertaking behavioral responses (Siegrist and Gutscher, 2008; Harries, 2012).

Ninth, a number of studies have examined the adoption of flood insurance and a number of their findings are relevant. In particular, if homeowners received information about the risk they will face over a longer time period (e.g., based on a 30-year period or the lifetime of a mortgage), they perceived more potential damage to their house than if they received the same risk information for 1 year (Keller et al., 2006). Also, the median length of time for holding onto flood insurance policies in the United States is 2 to 4 years, with people who have experienced small flood claims holding onto their insurance longer than those who experienced larger flood claims (Michel-Kerjan et al., 2012).

Finally, a number of studies on St. Louis found that insurance purchase was rather low, even with mandatory requirements (Kousky and Kunreuther, 2010; Kousky, 2011). Flood risk was a key determinant of the purchasing decision. As expected, there was more insurance purchase in the one percent annual chance floodplain due to the increased flood risk and mandatory purchase requirement. On the other hand, insurance purchase behind levees was less as residents perceived the area as “safe” (Kousky and Kunreuther, 2010; Kousky, 2011).

Development of appropriate strategies for risk communication is part of the overarching formulation of flood risk management (Chapter 3, Figure 3-3; Chapter 6). In developing risk communication strategies, key challenges identified from a further understanding of risk perception need to be considered:

1. The meaning of the phrase “100-year” floodplain and, to a lesser degree, the one percent annual chance flood is often misunderstood.

2. Awareness of risk does not always lead to actions to reduce or mitigate risk.

3. People assume that flood control structures are “safe” with no need to take additional actions to mitigate risk.

4. Experience with floods matters and influences the actions that residents and communities take to mitigate the impacts.

5. People will seek advice from friends, family, and neighbors on the determination of risk and actions to reduce flood risk.

6. Personalized risk assessment, based on experience and feelings, is more likely to motivate behavioral action than simply providing technical information about risks and consequences.

Understanding the above factors ensures that risk communication messaging is able to overcome the barriers associated with communicating levee-related flood risk.

BRIEF HISTORY OF RISK COMMUNICATION IN THE NFIP

Early in the NFIP’s history, it was thought that risk communication efforts would be largely undertaken by communities participating in the NFIP. FEMA provided guidance for local officials to use in efforts at the local or state level to reduce flood losses in high-risk areas and identified “areas behind unsafe or inadequate levees” as one of nine high-risk areas (FEMA, 1987). A “regular schedule for communication between engineering, planning, and emergency management personnel to provide consideration of levee hazards in land use decisions” was suggested for communities with levees (FEMA, 1987). For the most part, until 2005, FEMA used the term “risk” to describe a “hazard” as a consequence; probabilities other than flood frequencies were not considered.

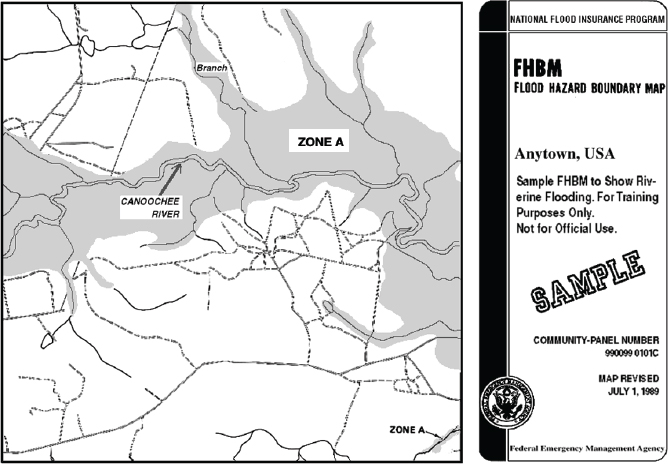

Early outreach to communities revolved around adoption of the initial mapping products: Flood Hazard Boundary Maps (FHBMs) and Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) (Figures 7-1 and 7-2). The FHBM, an official map of a community issued by FEMA, delineated Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs) and was prepared using available data or approximate methods to identify the areas within a community subject to inundation by a one percent annual chance flood (FEMA, 1995). The FIRM, also an official map of the community issued by FEMA, delineates both the special hazard areas and the applicable risk premium zones.1 The FIRM is developed using the

_______________

1 Title 44, Chapter 1, Code of Federal Regulations (1990), National Flood Insurance Program (Regulations for Floodplain Management and Flood Hazard Identification).

FIGURE 7-1 Example of a Flood Hazard Boundary Map.

SOURCE: FLOOD MAPS, May 1, 2008. Available online at http://www.fema.gov/pdf/nfip/manual200810/16map.pdf.

hydrologic and hydraulic analyses to develop base flood elevations and designate risk zones during flood insurance studies (FISs) (FEMA, 1995). The Digital Flood Insurance Rate Map (DFIRM) is a digital conversion of the paper FIRM that has been updated and georectified.

The 1968 National Flood Insurance Act intended that all SFHAs be identified and maps published within 5 years, and that these data be used to establish within 15 years the flood risk zones and associated insurance premium rates based on risks involved and accepted actuarial principles (FEMA, 1995). When it became evident that the needed FISs would not be completed in that time frame, Congress took action and authorized an Emergency Program (FEMA, 1995). Until the more detailed FIRMs were available, the FHBMs could be used to expand participation in the NFIP; this Emergency Program could offer insurance at nonactuarial, federally subsidized rates (FEMA, 1995). To further encourage participation in the NFIP, Congress required in the Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 that communities with flood-prone areas be notified of their flood hazards; this was also accomplished using the FHBM (FEMA, 1995). These initial risk (or hazard) communication efforts served to advise communities of their flood hazard as early as practicable, and sought to encourage action by communities to address and lessen their vulnerability. In the 1990s, the Mitigation Directorate was established within FEMA, Project Impact was launched (FEMA, 2011a), and the Community Rating System codified in the National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994 (H.R. 103-3191), all setting the stage for increased community involvement.

Historically there was little information about levee risk available to local communities other than FHBMs and FIRMs, which are focused on identifying the hazard, or areas flooded by the 0.2 percent and one percent annual chance floods for food insurance rating purposes. Today, the primary nationwide resource for information

FIGURE 7-2 A Flood Insurance Rate Map for a section of Greenville, Mississippi, along the Mississippi River. The blue areas are within the SFHA (Zone AE) and the gray area (Shaded Zone X) represents areas behind accredited levees.

SOURCE: FEMA Map Service Center. Available at http://map1.msc.fema.gov/idms/IntraView.cgi?KEY=93429510I&FIT=1

on flood-prone areas remains the FIRM. Private insurers assess exposure and offer flood insurance coverage based on FIRMs. To illustrate, preliminary estimates reported private-sector (re)insurance losses as a result of Hurricane Sandy in 2012 that range from $10 billion to $25 billion (BestWire, 2012; Insurance Insider Weekly Newsletter, 2012). However, this creates a challenge in leveed areas because older FIRMs do not explicitly identify areas as being behind accredited levees; thus, levee risk cannot be identified using the map alone.

Newer FIRMs, such as in Figure 7-2, indicate areas behind accredited levees as being Shaded Zone X; however, this zone designation is used to identify hazard areas of moderate to low risk. This lack of clear information promotes the misperception that areas behind levees are not subject to flooding and “safe.” This misperception is also promoted by the mandatory purchase requirement (Chapter 5).

TABLE 7-1: Timeline of Establishment of Programs and Efforts That Communicate Flood Risk Information Behind Levees to and from the National Level

| Program or Activity | Date of Establishment | Flood Risk Communication Efforts Specific to Levees |

| So You Live Behind a Levee (ASCE)a | 2010 | Public education booklet about risk living behind a levee |

| Silver Jackets (USACE, FEMA, and state agencies)b | 2006 | Flooding with some specifics on levees |

| National Flood Risk Management Program (USACE)c | 2006 | Reducing overall flood risk including appropriate use of levees |

| FloodSmart (FEMA)d | 2003 | Levee simulator Levee toolkit |

| Community Rating System (FEMA)e | 1990 | Credits for levee maintenance given to communities to reduce insurance rates |

| Stakeholder organizations (ASFPM and NAFSMA)f | 1976, 1978 | State and local flood and levee risk |

a See http://www.asce.org/Content.aspx?id=2147488910.

b See http://www.nfrmp.us/state/.

c See http://www.nfrmp.us/.

d See http://www.floodsmart.gov/floodsmart/.

e See http://www.fema.gov/national-flood-insurance-program/community-rating-system.

f See http://www.floods.org/.

CURRENT FLOOD RISK COMMUNICATION EFFORTS

Throughout its duration the NFIP and its risk communication strategy continued to evolve toward one that has a more engaged agency working in a shared effort with the many stakeholders that make use of and are impacted by the NFIP. A number of federal agencies, states, local communities, and nongovernmental organizations are actively engaged in flood risk communication efforts that share information about levees directly or indirectly and support the mission of the NFIP in general and risk communication about levees in particular (Table 7-1). A number of the more significant efforts in communicating levee flood risk are briefly described below.

FloodSmart

FloodSmart began in 2004 as a marketing campaign to increase the number of policies in force (Vrem, 2010). It has evolved into a multifaceted communication tool. Presently, FloodSmart, its website,2 and its associated activities are the primary communication avenues for information regarding the NFIP and the treatment of levees within the NFIP.3

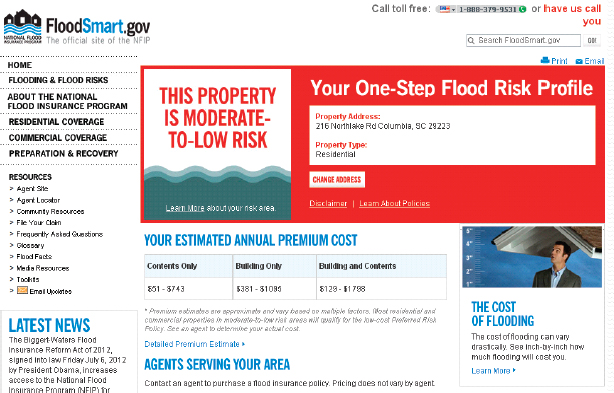

FloodSmart provides Web-based information in five main areas related to flood risk generally and flood risk behind levees specifically. First, flooding and flood risk includes information on causes of flooding, defining flood risk, tutorials on understanding flood maps as well as information regarding map changes and updating flood maps. In addition to this, the website has three multimedia and interactive applications or tools: one on flood risk scenarios, one on the cost of flooding, and a third called the levee simulator, which illustrates how levees work and the causes of levee failures. The second main topical area is the detailed information regarding the NFIP itself. Here the site describes coverage within the NFIP and when insurance is required, and locator information for insurance agents and estimations of premiums. The third area focuses on residential coverage which describes policy options for homeowners, renters, and condo owners/renters, including basic information, rates, what is covered,

_______________

2 See FloodSmart.gov.

3 FEMA has other Web-based applications and publications for communicating flood risk, for example, the eWatermark publication available online at http://www.nfipiservice.com/watermark/index.html.

FIGURE 7-3 FEMA’s one-step flood risk profile that provides quick information on flood risk, estimated flood insurance premiums, and insurance agents in the area.

SOURCE: www.floodsmart.gov/floodsmart.

questions for the agent, and locations of agents. The fourth area provides similar information for commercial properties. Finally, the last area communicates information on preparation and recovery, especially on what to do after the flood and how to file a claim.

On all of the FloodSmart webpages, there is an interactive one-step flood risk profile where one can insert the property address and the level of risk along with estimated annual premiums, and a list of agents serving the area appear (Figure 7-3). As an aid for communication, the site also has videos, media resources including public announcement scripts, and background information about the NFIP. A Levee Toolkit is available to educate citizens about flood risk associated with living behind a levee and information about flood insurance behind a levee.4 The toolkit does so by describing three scenarios a community might face: (1) levees are no longer accredited, (2) levees are newly accredited, and (3) levees are under review or provisionally accredited. The website is easy to navigate and filled with informative content for interested parties.

Risk MAP

Begun in FY 2009, Risk Mapping, Assessing, and Planning (Risk MAP) is the extension of FEMA’s map modernization efforts to improve flood hazard mapping through advanced technologies. According to FEMA, “The vision for Risk MAP is to deliver quality data that increases public awareness and leads to action that reduces risk to life and property”5 (Figure 7-4).

_______________

FIGURE 7-4 The vision for the Risk MAP life cycle, which begins with identifying risk, assessing risk, communicating risk, and mitigating risk.

SOURCE: http://www.fema.gov/rm-main.

The goals for Risk MAP, as identified in the Risk MAP multiyear plan (spanning FY 2010 through FY 2014), are to

Address gaps in flood hazard data to form a solid foundation for flood risk assessments, floodplain management, and actuarial soundness of the NFIP,

1. Ensure that a measurable increase of the public’s awareness and understanding of risk management results in a measurable reduction of current and future vulnerability to flooding,

2. Lead and support state, local, and tribal communities to effectively engage in risk-based mitigation planning resulting in sustainable actions that reduce or eliminate risk to life and property from natural hazards,

3. Provide an enhanced digital platform that improves management of limited Risk MAP resources, stewards information produced by Risk MAP, and improves communication and sharing of risk data and related products to all levels of government and the public,

4. Align Risk Analysis programs and develop synergies to enhance decision-making capabilities through effective risk communication and management.” (FEMA, 2009)

Thus, Risk MAP is both a program for planning and assessment and a platform for delivering high-quality georeferenced spatial data, initially focused on flood risk but with capabilities for multihazard risk assessments. Moving to a GIS-based platform permits rapid updates of technical data.

Living with Levees is a specific FEMA website within the Risk MAP program, devoted specifically to levee risk rather that a discrete program of activities.6 This website provides detailed information for a number of stakeholders including home and business owners; community officials; real estate, insurance, and lending professionals; technical partners (e.g. engineers, surveyors, contractors); and the media. Most of the links are to additional informational brochures or tools such as FloodSmart’s levee simulator. The website contains general information that is useful, but detailed technical information that could help households understand or mitigate their flood risks is limited. Most of the website features links to FEMA program descriptions, documents, and online tutorials on NFIP, and the use of geospatial information systems (GIS) in flood mapping.

_______________

6 See http://www.fema.gov/living-levees-its-shared-responsibility.

Community Rating System

The CRS is a part of the NFIP designed to provide incentives to communities to go beyond the minimum level of requirements of the NFIP. It rewards communities through discounts on flood insurance from 5 to 45 percent based on floodplain management and public information activities. Points are awarded in four broad categories (called a series): public information, mapping and regulations, flood damage reduction, and flood preparedness. Within each of these are a number of activities. For example, the public information category includes making information available on flood insurance rate maps and outreach projects (series 300) (FEMA, n.d.). Each activity has a maximum number of points allotted. In the public information series, for example, the maximum points are awarded for activities related to outreach projects (380). In the flood damage reduction activity series (500), the maximum points are awarded for activities related to acquisition and relocation of properties (3,200). The credit points are cumulative, and for each increment of 500 points earned, a reduction of 5 percent in the premiums for flood insurance is realized (FEMA, n.d.).

Out of the total number of communities in the NFIP (21,8817), only 1,211 are in the CRS program (approximately 5.5 percent). However, policies held within CRS communities represent 68 percent of the policies in force and 69 percent of the insurance in force8 (Bill Blanton, FEMA, personal communication, July 10, 2012). Once points are earned, classifications are awarded and premium reductions are given to the community. The majority of participating communities are in the introductory class (56 percent) with premium reductions of 5-10 percent, followed by the intermediate class (43 percent) with percent premium reductions of 15-25 percent, and then the advanced class (less than 1 percent) with premium reductions of 30 percent or more (FEMA, 2012).

High Water Mark Initiative

The High Water Mark Initiative (also known as Know Your Line: Be Flood Aware) is a recent initiative involving nine federal agencies,9 designed to raise flood awareness and motivate actions at the individual level to reduce risk.10 The initiative began in 2012 by soliciting six pilot communities to showcase the most severe flood that has affected the community by posting high-water-mark signs on prominent buildings. As such, it relies on local implementation to offer a testimony that identifies how high floodwaters have risen in the past. It is unclear as to whether the pilot program will illustrate high water marks behind the levee, pre-levee. This would be an important way to communicate flood risk.

National Flood Risk Management Program

The National Flood Risk Management Program (NFRMP) established by USACE in 2006 is designed to integrate and synchronize flood risk management programs across USACE, with federal, state, and local partners. The risk communication efforts of this program include providing risk information to the public from flood damage reduction infrastructure, improving public awareness and understanding of flood hazards and risk, and providing accurate floodplain management information to the public and decision makers. These goals are achieved through an inventory and assessment of levees that are under USACE jurisdiction (the National Levee Database, discussed in Chapter 8), and working collaboratively with FEMA to jointly develop risk communication strategies.

An innovative, collaborative initiative, the Silver Jackets Program is designed to bring together state, federal, and local agencies to “learn from each other and apply this knowledge to reduce risk.” Part of the larger USACE National Flood Risk Management Program, the goals of the Silver Jackets program are to

_______________

7 As of June 2012.

8 Insurance in force is the total of the limit of insurance purchased on each policy.

9 FEMA, National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Park Service, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and U.S. Small Business Administration.

10 See http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/conferences/2012/securitysummit/presentations/brown.pdf.

• Create or supplement a mechanism to collaboratively address risk management issues, prioritize those issues, and implement solutions;

• Increase and improve risk communication through a unified interagency effort;

• Leverage information and resources, including providing access to such national programs as FEMA’s Risk MAP program and USACE’s Levee Inventory and Assessment Initiative;

• Provide focused, coordinated hazard mitigation assistance in implementing high-priority actions such as those identified by state mitigation plans;

• Identify gaps among the various agency programs and/or barriers to implementation, such as conflicting agency policies or authorities, and provide recommendations for addressing these issues.11

The Silver Jackets process is centered at the state level and supported at the federal level primarily by USACE and FEMA. State agencies form federal-state-stakeholder teams that meet regularly to discuss a state’s flood risk management priorities among stakeholders. Currently, 33 states have interagency, Silver Jacket teams. With the state in the lead, each team is encouraged to include other federal agencies that could advance flood risk management goals in the Silver Jackets forum, for example, NOAA-National Weather Service, Department of the Interior, and the USGS.

Living Behind a Levee

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) is a nonprofit professional society. One of its many roles is to help protect public safety through improved learning within the profession, but also among the general public. One key focus of the ASCE is to addresses disaster preparedness and response. The flood risk communication aspect of the ASCE is best seen in the preparedness guide, So, You Live Behind a Levee! What You Should Know to Protect Your Home and Loved Ones from Floods. Written for both the engineering and nonengineering public, the brochure emphasizes four essential levee facts: (1) flooding will happen, (2) risks associated with flooding vary, (3) no levee is floodproof, (4) actions taken now will save lives and property.

CONTEMPORARY FLOOD RISK MAPPING

Twenty-first century geospatial information technology has opened the door for vastly improved risk identification and communication. The development of GIS has provided decision makers, land-use planners, floodplain managers, and numerous other parties connected with flood hazard to conduct detailed analyses of the multiple flood scenarios that bring together the built environment with the natural environment to create flood risk. Use of GIS in management of communities is ubiquitous, and few communities lack some form of GIS. FEMA’s DFIRMs provide an example of the use of GIS to identify flood hazards.

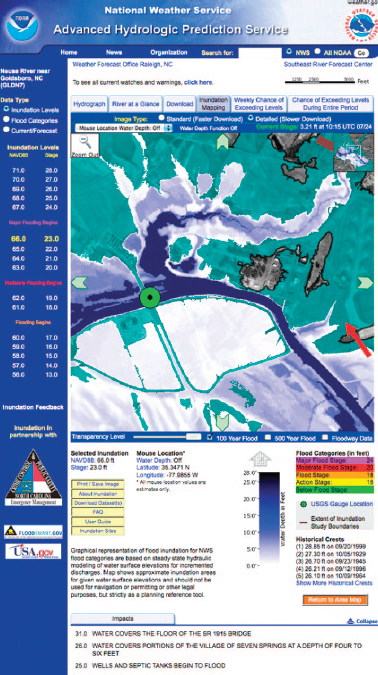

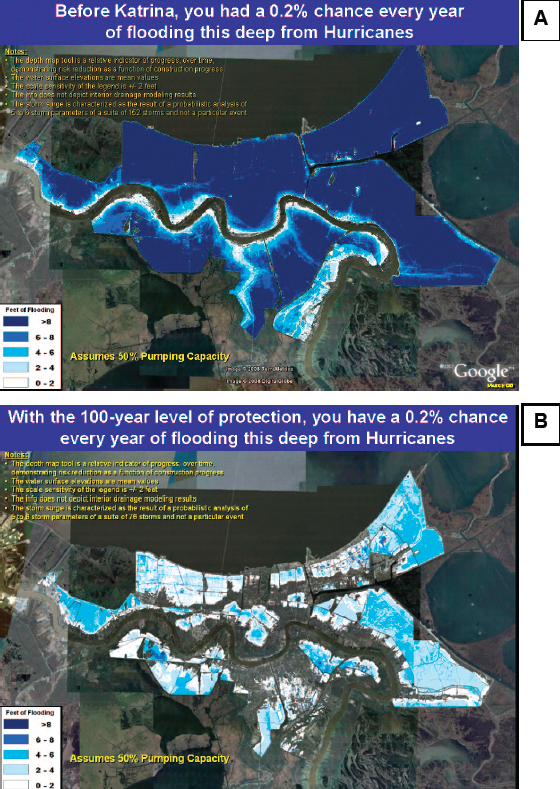

Over the last decade, considerable effort, at the global scale, has been placed on research to improve the representation of flood risks on flood maps and to make the maps both dynamic and interactive. Today, maps are available that permit those living in the floodplain to determine the level of inundation of their property under various flood condition scenarios; to examine the consequences of a particular flood event, taking into account the risk-based analysis that produced the information; and to link real-time weather information with flood potential in a given region (Figure 7-5 and 7-6). New flood maps not only illustrate the floods and their consequences but also can dynamically portray such elements as availability of evacuation routes, shelter status, and threat levels. The future of such approaches is illustrated in the National Research Council report, Mapping the Zone Improving Flood map Accuracy (NRC, 2009).

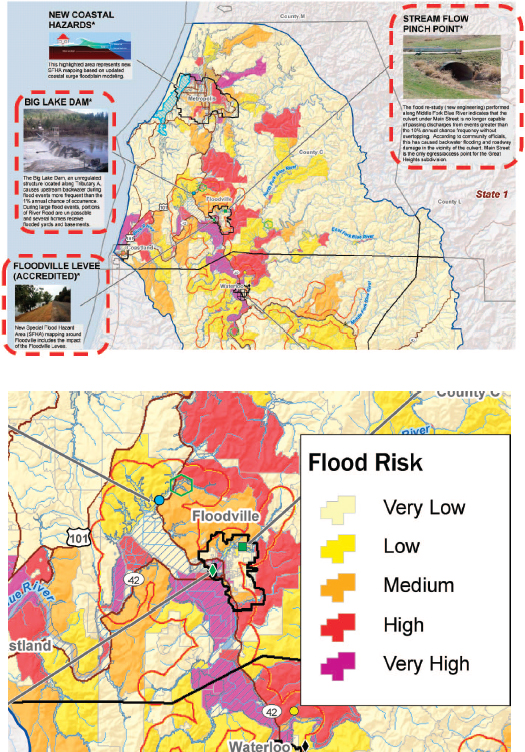

FEMA’s Risk MAP program is carefully examining new tools and, where appropriate, using them to better communicate flood risk under a variety of circumstances (Figure 7-7). Tying risk-based analysis to GIS will enable those living behind levees to gain a true perspective of their flood risk.

_______________

11 Both quotations are from http://www.nfrmp.us/state/.

FIGURE 7-5 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (NWS) flood inundation map of a segment of the Neuse River near Goldsboro, North Carolina, showing the extent of flooding when water levels are forecast to rise to a stage of 23 feet (blue) and the location of the one percent annual chance floodplain (blue green) from a FEMA map. The darker the blue, the greater is the depth of inundation. The water depth is 0 to 2 feet near the edge of the Seymour Johnson Air Force Base runway (red arrow). The green circle shows the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) stream gauge where the NWS provides the river forecast. The topographic data, digital elevation models, and hydraulic models underlying the map were produced by the USGS office in Raleigh and the North Carolina Floodplain Mapping Program.

SOURCE: http://water.weather.gov/ahps/inundation.php. Accessed January 28, 2013.

FIGURE 7-6 Flood risk maps for New Orleans, illustrating differences in levels of inundation for a 0.2 percent flood event (A) before and (B) after the completion of the post-Katrina one percent hurricane risk reduction levees. Water surface elevations are mean values, with a sensitivity of ±2 feet. The maps assume that the pumps inside the levees that evacuate interior floodwaters are operating at 50 percent capacity.

SOURCE: USACE, New Orleans District, http://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/hps2/hps_risk_depth_map.asp. Accessed February 17, 2013.

FIGURE 7-7 A Risk MAP pilot watershed-based flood risk map of “Watershed USA” containing nonregulatory data to aid in risk communication. At the top, the upper portion of Watershed USA is shown, containing detailed information about a variety of items influencing flood risk in the watershed. At the bottom, a closer view of the town of Floodville shows the different levels of flood risk by area.

SOURCE: Maps courtesy of FEMA Risk MAP.

EFFECTIVE FLOOD RISK COMMUNICATION

While FEMA, the USACE, and other groups have important roles at the federal level in providing information on flood risk, it is local and state governments that drive behavioral changes to mitigate the risk. This is recognized and built into communication efforts implemented at the national level, described above; these federal agencies maintain a focus on communicating at the local level. Also, organizations with a focus on the state and local levels that facilitate communication of the state and local perspective to the national scale play a particularly important role (Box 7-1).

Some flood-related risk communication efforts are very successful (Box 7-2), but metrics and evaluations of communication efforts are difficult to find. FEMA’s annual national surveys are an exception. These surveys were conducted in 2010 and 2011 to evaluate progress toward achieving goal 2 of Risk MAP, above, to “ensure that a measurable increase of the public’s awareness and understanding of risk management results in a measurable reduction of current and future vulnerability to flooding.”12 The surveys found that:

• the percentage of community members who believed that their community was at risk from flooding was 31 percent in 2012 and 41 percent in 2011, while fewer than 23 percent of those believing their community to be at risk believed that their home was at risk in 2011;

• 68 percent of local public officials thought their community was at risk for flooding;

• 47 percent of respondents expect to hear about flood risk from the mayor;

• local news, phone calls, and mailings were also preferred methods of communication at 87 percent, 25 percent, and 24 percent, respectively;

• when asked about how frequently people heard from local officials about flood risk, the most common response was “never” in 2010 (41 percent) and in 2011 (45 percent); and

• those in coastal areas were slightly more aware of flood risk to their community (54 percent) or home (19 percent) (FEMA, 2011b).

California, in partnership with FEMA and USACE, recently sent mailed notices to property owners located behind a state-federal project levee as part of their Flood SAFE California Flood Risk Notification Program.13The Living with Levees: Know Your Flood Risk mailing campaign was evaluated through a readership survey to determine and improve effectiveness in 2010 and 2011.14 In 2010, 77 percent of survey respondents said that the mailing raised their awareness of flood risk “a lot” or “somewhat” (31 percent and 46 percent, respectively). This improved in 2011, with 85 percent noting that the mailing raised awareness of flood risk “a lot” or “somewhat” (28 percent and 57 percent, respectively). The mailing encouraged 12 percent and 14 percent of survey respondents to purchase flood insurance in 2010 and 2011, respectively. This corroborates risk awareness key principle 2, above, that although the mailing was effective at raising flood risk awareness, such awareness doesn’t necessarily translate into action, that is, buying an insurance policy.

Information Access and Security: The Impact on Risk Communication

As discussed throughout this chapter, information regarding levee-related flood risk is becoming more sophisticated and accessible with, for example, actions taken to generate levee inventories and improved mapping. Furthermore, a modern risk analysis and better probability models and damage estimates (resulting in risk-based premiums at the structure level) will greatly increase communication of true risk to NFIP policyholders. New and improved information can be paired with development of community flood risk management strategies, including mitigation measures to reduce premiums. Improved mapping can be used to engage the private sector, so that insurance policies that are complimentary to the NFIP are offered to the public. Furthermore, the insurance industry

_______________

12 One thousand telephone interviews were conducted at random to households in FEMA’s 10 regions; 36 percent of respondents were from Risk MAP project areas, 87 percent of whom were homeowners and 12 percent renters.

13 See http://www.water.ca.gov/floodmgmt/lrafmo/fmb/fas/risknotification/.

14 Information included in this discussion was provided by FloodSmart California staff at the second meeting of this committee.

BOX 7-1

Stakeholder Organizations

The Association of State Floodplain Managers (ASFPM) is an organization of professionals involved in floodplain management, flood hazard mitigation, and flood preparedness and response. The mission of the organization is to “promote education, policies, and activities that mitigate current and future losses, costs, and human suffering caused by flooding, and to protect the natural and beneficial functions of floodplains—all without causing adverse impacts.”a The ASFPM is organized into state chapters and, as such, ASFPM supports an avenue of communication between the states and the federal and local levels. ASFPM activities that promote communication include education of floodplain managers, technical conferences to bring together practitioners, and involvement in the establishment of FEMA’s Community Rating System to reward communities for floodplain management practices. b

Similarly, the National Association of Flood & Stormwater Management Agencies (NAFSMA) “is an organization of public agencies whose function is the protection of lives, property and economic activity from the adverse impacts of storm and flood waters. The mission of the Association is to advocate public policy, encourage technologies and conduct education programs which facilitate and enhance the achievement of the public service function of its members.”c Self-described as its members’ voice in Washington, D.C., NAFSMA represents and communicates the perspective of state and local public agencies at the national level.

_______________

a See http://www.floods.org/.

b See http://www.floods.org/index.asp?menuID=425&firstlevelmenuID=179s&iteID=1.

is in a position to support effective risk communication through its policy marketing, when provided with access to flood risk information.

Availability of information regarding the location and status of the nation’s levees has a direct impact on successful flood risk communication efforts. Some data elements in the USACE’s National Levee Database contain information about the integrity of the levees contained therein. Access to this information is restricted to government officials and is not available to the public. Restricting access to information regarding levees limits the ability of businesses, individuals, and in many cases, first responders to become aware of and properly prepare for possible emergency situations. Three recent reports (NRC, 2012a,b; Galloway et al., 2011) have addressed the need for full access to such information and recommended that this needed information be routinely released.

Understanding risk perception and evaluations of risk communication efforts sheds light on the importance of local communication and clear messaging, as well as challenges such as the assumption that flood control structures are “safe.” Insight gathered at public meetings of this committee indicates that risk communication efforts surrounding NFIP levees have an advantageous window of attention during three situations: (1) after a flood disaster, (2) through the mapping programs, and (3) when a community participates in FEMA’s CRS program. It also appears that during these three situations, particularly situations 1 and 2, considerable confusion and controversy or considerable success in communicating risk can occur.15

_______________

15 This assessment is based on information gathering efforts during committee meetings in St. Louis, Missouri, Dallas, Texas, and Sacramento, California.

BOX 7-2

Flood Insurance Retention in Sacramento, California: A Transitional Community

The city of Sacramento sits at the confluence of the Sacramento and American rivers. Most of the city lies within the floodplains of these two rivers, around 55,000 acres containing approximately 110,000 damageable structures valued at over 30 billion dollars. More than 300,000 people live in these floodplains. The Sacramento levee system extends for approximately 100 miles around the city.

In 1978, Sacramento joined the NFIP and was mapped out of the one percent annual chance regulatory floodplain because of the levee system. Following a record flood in 1986, the city was mapped back into the SFHA (Zone A-99) in 1989. Improvements to the levee systems resulted in a revised Flood Insurance Rate Map for the American River area in 2004 and removal from the one percent annual chance regulatory floodplain.

Corresponding to the release of the 2004 map for the American River area, the Sacramento Area Flood Control Authority (SAFCA) commenced a 6-month flood insurance outreach campaign targeting approximately 46,000 property owners who were to be released from the mandatory purchase requirement.a The outreach campaign had several goals: (1) alert property owners to the risk of levee failure in their community, (2) urge property owners to take responsibility for this risk by maintaining a flood insurance policy, and (3) encourage property owners who are no longer subject to the mandatory purchase requirement to continue to carry a flood insurance policy (a preferred risk policy or PRP), and (4) urge stakeholders to engage in Sacramento’s policy retention efforts. The campaign was implemented in five phases targeting the insurance agent, elected officials, lenders, property owners, and the media.

The choice to center part of the outreach plan around PRPs was based on a survey, conducted in March 2003, targeting homeowners in the American River area. Respondents said they were willing to maintain their insurance policies based on two conditions: (1) once the MPR was lifted, they could purchase flood insurance for approximately half what they currently paid;, and (2) if local flood officials communicated flood risk.

Seventy percent of the property owners released from the 2005 mandatory purchase requirement maintained flood insurance. Lessons learned include the effectiveness of an outreach campaign coinciding with a community’s release from the flood insurance program and the importance of the more affordable PRP in encouraging policy retention (SAFCA, 2012).

______________

aThe campaign was jointly funded by NFIP and SAFCA (75 percent and 25 percent, respectively).

To be effective, levee risk communication efforts need to be anchored in several principles:

• delivery at the local level;

• products tailored to individual households, communities, and other stakeholders;

• delivery from a credible and trusted source;

• long-term (meaning efforts should extend over a period of time);

• contain consistent, correct, and nonconflicting content;

• encourage or motivate some behavior change;

• account for the values of target audiences or communities;

• employ multimodal networks; and

• provide repeat messaging (Peters et al., 1997; Mileti and Peek, 2002; Tinker and Galloway, 2008).

FEMA and others involved in risk communication at all levels should incorporate contemporary risk communication principles in the development of flood risk communication strategies and implementation

efforts. Seizing key windows of opportunity to communicate levee-related flood risk at the local level is critical to success. Correcting misperceptions, for example, that if you live behind a levee you are “safe,” is also critical.

A systematic evaluation of risk communication efforts against measurable outcomes such as increases in insurance purchase, increases in mitigation activities, or a downward trend in damages could yield significant insights regarding levee-related risk communication. Appropriate assessment tools for monitoring the success of risk communication programs are critical, including (1) baseline information on the existing status of flood losses prior to program implementation, if available; and (2) predefined metrics for assessing the effectiveness in reducing risk as measured by increases in flood insurance policies, increases in the number and type of mitigation activities, improvements in the percentage reductions in NFIP premiums, and reductions in overall losses, among others. FEMA should support evaluation of the success of risk communication efforts, including at the community level when appropriate, that is informed by appropriate assessment tools such as baseline information and predefined metrics. Agencies and organizations outside of FEMA involved in communicating risk behind levees might find value in evaluating success of efforts as well.

Bell, H. M., and G. A. Tobin. 2007. Efficient and effective? The 100-year flood in the communication and perception of flood risk. Environmental Hazards: Human and Policy Dimensions 7(4): 302-311. BestWire. 2012. Update: Sandy losses by company: Insurance total could reach $25 billion. Available online at http://www.programbusiness.com/News/Sandy-Losses-by-Company-Insurance-Total-Could-Reach-25-Billion. Accessed February 21, 2013.

Botzen, W. J. W., J. Aerts, and J. C. J. M. van den Bergh. 2009. Willingness of homeowners to mitigate climate risk through insurance. Ecological Economics 68(8-9): 2265-2277. Bourque, L. B., R. Regan, M. M. Kelley, M. M. Wood, M. Kano, and D. S. Mileti. 2012. An examination of the effect of perceived risk on preparedness behavior. Environment and Behavior, doi:10.1177/0013916512437596. Bubeck, P., W. J. W. Botzen, and J. C. J. H. Aerts. 2012. A review of risk perceptions and other factors that influence flood mitigation behavior. Risk Analysis 32(9): 1481-1495. FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 1987. Reducing Losses in High Risk Flood Hazard Areas: A Guidebook for Local Officials, FEMA 116. Available online at http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=1508. Accessed November 14, 2012.

FEMA. 1995. Managing Floodplain Development in Approximate Zone A Areas: A Guide for Obtaining and Developing Base (100-Year) Flood Elevations, FEMA 265. Available online at http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=1526. Accessed November 12, 2012.

FEMA. 2009. Risk Mapping, Assessment, and Planning (Risk MAP) Multi-Year Plan: Fiscal Years 2010-2014. Available online at http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=3587. Accessed December 6, 2012. FEMA. 2011a. FEMA Mitigation and Insurance Strategic Plan 2012-2014.

FEMA P-857. Available online at http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=4903.

FEMA. 2011b. 2011 Public Survey Findings on Flood Risk. Available online at http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=6259. Accessed November 20, 2012.

FEMA. 2012. Community Rating System Participation National Map. Available online at http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=6200. Accessed December 8, 2012.

FEMA. n.d. NFIP: Community Rating System: A Local official’s guide to saving lives preventing property damage reducing the cost of flood insurance. Available online at http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=3655. Accessed November 29, 2012.

Fischhoff, B., and J. Kadvany. 2011. Risk: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Galloway, G. E., G. B. Baecher, K. Brubaker, and L. E. Link. 2011. Review and Evaluation of the National Dam Safety Program. College Park, MD: Water Policy Collaborative. Available on line at www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=5794. Accessed February 21, 2013.

Grothmann, T., and F. Reusswig. 2006. People at risk of flooding: Why some residents take precautionary action while others do not. Natural Hazards 38(1-2): 101-120.

Harries, T. 2012. The anticipated emotional consequences of adaptive behaviour-impacts on the take-up of household flood-protection measures. Environment and Planning A 44(3): 649-668.

Harvatt, J., J. Petts, and J. Chilvers. 2011. Understanding householder responses to natural hazards: Flooding and sea-level rise comparisons. Journal of Risk Research 14(1): 63-83.

Insurance Insider Weekly Newsletter. 2012. Reported Sandy losses to $10.4bn. December 17, Issue 506.

Kellens, W., T. Terpstra, and P. De Mayer. 2012. Perception and communication of flood risks: A systematic review of empirical research. Risk Analysis doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01844.x.

Keller, C., M. Siegrist, and H. Gutscher. 2006. The role of the affect and availability heuristics in risk communication. Risk Analysis 26(3): 631-639.

Keller, C., A. Bostrom, M. Kuttschreuter, L. Savadori, A. Spence, and M. White. 2012. Bringing appraisal theory to environmental risk perception: A review of conceptual approaches of the past 40 years and suggestions for future research. Journal of Risk Research 15(3): 237-256.

Kousky, C. 2011. Understanding the demand for flood insurance. Natural Hazards Review 12(2): 96-110.

Kousky, C., and H. Kunreuther. 2010. Improving flood insurance and flood-risk management: Insights from St. Louis, Missouri. Natural Hazards Review 11(4): 162-172.

Lindell, M. K., and R. W. Perry. 2012. The protective action decision model: Theoretical modifications and additional evidence. Risk Analysis 32(4): 616-632.

Ludy, J., and G. M. Kondolf. 2012. Flood risk perception in lands “protected” by 100-year levees. Natural Hazards 61(2): 829-842.

Michel-Kerjan, E., S. Lemoyne de Forges, and H. Kunreuther. 2012. Policy tenure under the U.S. National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Risk Analysis 32(4): 644-658.

Mileti, D. S., and L. A. Peek, 2002. Understanding individual and social characteristics in the promotion of household disaster preparedness. In New Tools for Environmental Protection: Education, Information, and Voluntary Measures. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Morgan, M. G., B. Fischhoff, A. Bostrom, and C. J. Atman. 2001. Risk Communication: A Mental Models Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 1989. Improving Risk Communication. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC. 2009. Mapping the Zone, Improving Flood Map Accuracy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2012a. Dam and Levee Safety and Community Resilience: A Vision for Future Practice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2012b. Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Peters, R. G., V. T. Covello, and D. B. McCallum. 1997. The determinants of trust and credibility in environmental risk communication: An empirical study. Risk Analysis 17(1): 43-54.

Pielke, R. A. 1999. Nine fallacies of floods. Climatic Change 42(2): 413-438.

SAFCA (Sacramento Area Flood Control Agency). 2012. Data on Flood Insurance Purchase and Retention in the City of Sacramento, Memo to the Committee on Levees and the National Flood Insurance Program: Improving Policies and Practices from Tim Washburn, Director of Planning. Sacramento, CA: SAFCA.

Siegrist, M., and H. Gutscher. 2008. Natural hazards and motivation for mitigation behavior: People cannot predict the effect evoked by a severe flood. Risk Analysis 28(3): 771-778.

Soane, E., I. Schubert, P. Challenor, R. Lunn, S. Naredran, and S. Pollard. 2010. Flood perception and mitigation: The role of severity, agency, and experience in the purchase of flood protection, and the communication of flood information. Environment and Planning A 42(12): 3023-3038.

Terpstra, T., M. K. Lindell, and J. M. Gutteling. 2009. Does communicating (flood) risk affect (flood) risk perceptions? Results of a quasi-experimental study. Risk Analysis 29(8): 141-1155.

Tinker, T., and G. E. Galloway. 2008. How Do You Effectively Communicate Flood Risks? Looking to the Future. Available online at: http://www.emforum.org/vforum/BAH/How%20Do%20You%20Effectively%20Communicate%20Flood%20Risks.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2012.

Tobin, G. A. 1995. The levee love-affair—a stormy relationship. Water Resources Bulletin 31(3): 359-367.

Vrem, M. J. 2010. Communicating Risk: Ten key learnings from the FloodSmart campaign. Available online at: http://www.asfpmfoundation.org/pdf_ppt/2010_GFW_Forum_Background_Reading.pdf#page=66. Accessed November 20, 2012.

USGS (U.S. Geological Survey). 2010. Flood of April and Map 2008 in Northern Maine, Fact Sheet 2010-3003. Available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2010/3003/pdf/fs2010-3003.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2012.

Wood, M. M., D. S. Mileti, M. Kano, M. M. Kelley, R. Regan, and L. B. Bourque. 2012. Communicating actionable risk for terrorism and other hazards. Risk Analysis 32(4): 601-605.