Insuring Properties Behind Levees

Insurance is a method of prefunding (usually over time) the adverse consequences of a loss so as to have available funds to pay damages when they arise. It is a legal contract that transfers some of the financial consequences of an uncertain low-probability but high-consequence peril to another party (called an insurer) in return for periodic relatively low payments (premiums). If an event covered by the insurance contract occurs, and if coverage is triggered by conditions detailed in the contract, then the insurer will indemnify the insurance purchaser up to the limits of the insurance policy in accordance with the terms of the contract (e.g., the deductible, the policy limits, proof of loss, etc.). Thus, the value of insurance arises at the time of a covered loss, and can thus be viewed as a hedging instrument against the financial consequences of a loss.

In insurance nomenclature, the causes of loss is called a peril, and a condition or situation that increases either the likelihood or severity of the peril occurring is called a hazard. Risk, on the other hand, is the term used to designate the loss consequence of the realization of the uncertain peril, and it may be financial or nonfinancial in nature (e.g., reputational loss). Thus for example, fire is a peril, storing oily rags next to a gas water heater is a hazard for the peril of fire, and the loss of property and the financial losses due to fire-related property destruction is the risk. Concerning the peril of flooding, building unelevated property below the base flood elevation in a floodplain is a hazard, and the financial consequences of partial or total destruction of property due to flooding is the risk that the property owner faces. Risk is an adverse consequence of uncertainty concerning perils, and without uncertainty there can be no risk.

Not all risk can be insured in the private market (i.e., by private insurers) but when available, insurance can be part of an effective risk management strategy. Other parts of the risk management process include risk identification, risk assessment, risk mitigation or control, and risk communication. Insurance is not a risk mitigation technique, however, because the legal insurance contract does not change the physical probability or the severity of a realized peril, but rather it just allocates the cost to another party.1

From the perspective of the purchaser, insurance is a viable risk transfer technique when the probability of the event occurring, p, is relatively small and the consequence or loss, L, is relatively large (so as to be difficult to financially assume all at once by the purchaser without insurance), but such that the expected value in any given

_______________

1 Insurance that is truly risk-based priced can motivate policyholders to mitigate risks to lower premium costs, but it is not that insurance itself that mitigates the risk, but rather the affirmative actions of the policyholder to lower frequency or severity.

year p x L is affordably small as a basic for an annual insurance premium calculation.2 This expected value is called the “pure premium” in insurance and is subsequently “loaded” or modified to reflect insurance underwriting costs, claim adjusting and settlement costs, and returns to the providers of capital to the insurance organization. An additional loading is added to reflect the level of uncertainty in the estimation of the pure premium. Once loaded, the result is the actual premium charged to the purchaser of insurance.

As part of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), the insurance component is one pillar to address catastrophic loss potential from floods (other pillars include motivating building and land-use restrictions in vulnerable areas and construction of dams, levees, and other structures). NFIP insurance is available to all property owners in communities that participate in the program. Coverage for flood damages extends up to $250,000 dollars for residential structures and $100,000 dollars for residential contents and $500,000 for business structures and $500,000 dollars for business contents.3 Those that require greater amounts of coverage than available from the NFIP have access to additional flood insurance through private industry, e.g., their property insurance carrier.

Pricing is done in essentially the same manner in all areas of insurance with some differences in models and assumptions corresponding to the characteristics of the different types of insurance. Property and casualty insurance (also known as hazard insurance or general insurance in some areas) generally has a shorter contract duration, usually exists in a more highly regulated environment than life insurance, and has more complicated claims structure (with more correlated losses, the potential for multiple claims within the policy period, etc.). These characteristics have led financial/actuarial pricing formulas specifically tailored to the property or liability arena, which are somewhat distinct from the models used for pricing life and health insurance. A brief introduction to various aspects of property insurance pricing including manual rate setting and individual risk rating is presented. (More detailed examination of pricing of general property insurance is given by Ai and Brockett [2008] and by the Casualty Actuarial Society [1990].)

An (oversimplified) essential representation of pricing of insurance policies is that prices (or charged rates) should equal the expected present value of the future losses on the contract augmented by a load for expenses, plus an insurer profit load, plus a load to compensate the insurer for risk bearing (see equation (5-1)). Hence, the price for insuring a risk exposure is given by

![]()

where P is the price, E is the expectation operator representing the taking of the statistical expectation of the random variables involved in the brackets, and where

k1 = the load for expenses (marketing underwriting, administration, taxes, claims adjusting, commissions, and general operating expenses);

_______________

2 For insurance to be a viable alternative for an insurer to offer, there needs to be additional conditions that mitigate the financial hazard being assumed by the insurer so that the risk-assuming insurer itself does not go insolvent and can adequately manage the financial exposure they take on. These ideal conditions for a risk to be insurable include that (1) there be a large number of independent homogeneous exposure units to be insured (so the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem from statistics is available to the insurer for pooling and spreading risk among clients); (2) losses that occur are accidental; (3) a catastrophe cannot occur that affects a large number of exposure units simultaneously (this high correlation between losses thus defeating the independence of the exposure units and mitigating the insurers’ use of the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem); (4) losses must be definite and measurable (so they can be priced); and (5) the probability distribution for losses should be determinable (so prices can be set). In addition to the above characteristics of a risk to be insurable, there are behavioral conditions that the customer can create which will make the insurer reluctant to offer insurance. One of these is adverse selection, which can occur when the individuals who have a higher likelihood of experiencing losses are disproportionately drawn to buying insurance defeating the risk pooling needed by insurers (e.g., if only high-flood-risk property owners seek flood insurance). Finally moral hazard also needs to be considered by insurers, where moral hazard is the term used to describe the behavioral property that can arise wherein the people who are insured will take fewer precautions than those who are not insured simply because they have insurance and are not fuly responsible for their losses. This escalates costs to insurers, and if severe moral hazard or adverse selection is anticipated, then insurance will not be offered (Baranoff et al., 2009).

3 See floodsmart.gov.

k2 = profit load (included so as to allow the capital suppliers to obtain a “fair” or competitive rate of return on capital);

k3 = load for bearing uncertainty in future cash flows;

Ti = (possibly random) time until payment of the ith claim during the policy coverage period;

Li = (possibly random) dollar severity realized in the ith claim, also called the severity (or size of loss) of the loss exposure;

N = (possibly random) number of claims incurred during the policy period, also called the frequency;

V(Ti) = the discounted present value of $1 payable at time Ti (a priori this being a random stochastic process or a random variable).

Usually V(Ti) is taken to have the form V(Ti) = vTi where v = 1/(1 + r) is the discount factor based on an interest rate r. Stochastic models taken for N often include Poisson (for rare events) and binomial distributions. Statistical distributions chosen for Li generally depend on the particular hazard situation or peril involved. Indeed, the determination of appropriate statistical distributions and the dependence structure for N and Li is a crucial part of property insurance pricing. (See Klugman et al. [2008] for explicit loss distributions models used in insurance pricing.)

Once calculated, these theoretical prices may be modified for political, social, or market competition reasons. For example, political or regulatory considerations may force the company to deviate from the theoretically derived prices and constrain or suppress rates (Witt and Hogan, 1993). Such regulatory intervention (and social influences) upon the mathematically derived pricing formulas occurs more in property insurance lines wherein purchase is mandated by contractual obligations (e.g., homeowners’ insurance on mortgaged homes, comprehensive collision insurance on financed automobiles, etc.) and whose purchase is deemed .mandatory for social reasons (e.g., automobile insurance, workers’ compensation, flood insurance4) (Ai and Brockett, 2008). Most state regulations impose the conditions that rates (or premiums) cannot be inadequate (to ensure solvency), excessive (to prevent excessive profits), or of an unfairly discriminatory nature (for social equity) (Ai and Brockett, 2008).

Pricing Property Insurance Using “Manual Rates”

The notion of “manual rating” is setting the rate (or price) based on a basic rating table (or tables) that produces a price per unit for different classes of risks. From such tables the user can obtain a numerical value (say, dollars to charge per $1,000 of coverage) that is then applied to obtain a price for any designated risk within the class of risks covered by the table. Such manual rates are used generally to price homogeneous groups of exposure risks and are not tailored to the idiosyncratic characteristics of any specific individual. For such manually rated policies, the issue is how to determine the table entries from which the appropriate rates can be read.

Manual rate encompasses two basic methods: the loss ratio method and the pure premium method (Casualty Actuarial Society, 1990). The pure premium method bases the rate on the expected fundamental loss exposure probability distribution itself. Mathematically,

![]()

In equation (5-2), R denotes the rate per unit of exposure, E[L] denotes the expected loss per unit of exposure (called the pure premium or actuarial value), F denotes the per-exposure unit fixed expense, V is a variable expense factor, and Q is a risk contingency factor that also incorporates anticipated profit. Essentially, this is analogous to equation (5-1) in that it says the rate should be sufficient to pay expected losses after allowing for required profits and fixed and variable expenses (Ai and Brockett, 2008).

The expected loss per unit of exposure is calculated as the discounted present value of the loss(es) per exposure

_______________

4 According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency revised edition of the Mandatory Purchase of Flood Insurance Guidelines (FEMA, 2007), “The mandatory purchase law directed the Federal agency lender regulators and Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) to develop and adopt regulations requiring lenders subject to their jurisdiction not to make, increase, renew, or extend any loan on applicable property unless flood insurance is purchased and maintained to protect that property securing loans in high flood risk areas.”

unit, ![]() . After calculating this value for each possible rating class, a table (or set of tables) of values is created such that every possible exposure unit is uniquely found within a table. The coverage rate for a new exposure is ascertained by first determining the exposure’s class, and then reading the multiplicative factor for this class from the corresponding table. Ultimately, by multiplying the number of exposure units encompassed by the risk exposure to be priced times this factor, a premium is determined. The difficulty in applying this method is appropriately stochastically modeling the frequency, N, and severity, Li, variables and their dependencies. Many books on statistical analysis have been devoted entirely to this topic (cf. Klugman et al., 2008).

. After calculating this value for each possible rating class, a table (or set of tables) of values is created such that every possible exposure unit is uniquely found within a table. The coverage rate for a new exposure is ascertained by first determining the exposure’s class, and then reading the multiplicative factor for this class from the corresponding table. Ultimately, by multiplying the number of exposure units encompassed by the risk exposure to be priced times this factor, a premium is determined. The difficulty in applying this method is appropriately stochastically modeling the frequency, N, and severity, Li, variables and their dependencies. Many books on statistical analysis have been devoted entirely to this topic (cf. Klugman et al., 2008).

The second method, called the loss ratio method, is really a premium adjustment method as opposed to a premium-setting method. It assumes a current rate (R0) and determines a rate change for the next year by multiplying by an adjustment factor (A) to obtain a new rate R = AR0. The adjustment factor (A) is the ratio of the experienced loss ratio (Y) to a prespecified target loss ratio (T). Mathematically, R = AR0, where R0 is the current rate, A = Y/T, and Y = L/[(R0)(e)], where L denotes the current period experienced losses and e is earned exposure for the experience period. The target T = (1 - V - Q)/(1 + M), where V denotes the premium-related expense factor, Q is the factor for contingencies and profit, and M is the ratio of nonpremium-related expenses to losses. The loss ratio method (by construction) is not applicable when a current rate is unavailable (such as for new lines of business). Still, it allows the insurer to obtain new rates for the next period by updating the previous period’s rates. Brockett and Witt (1982) show that “when current prices are set by a regression methodology based on past losses, and the loss ratio method is used to adjust prices, then an autoregressive series is obtained, thus partially explaining insurance pricing cycles". Although the loss ratio method and the pure premium method are constructed from different perspectives, one can show that the methods yield the same prices given the same data (cf. Casualty Actuarial Society, 1990).

Individual Risk Rating

To obtain prices for individual exposure units, one can make modifications to the manual rates to accommodate for individual characteristics. A basic approach is to use a so-called credibility formula,5 where individual loss experience is incorporated with an estimation of expected losses for the risk class derived from some other source to obtain a blended or averaged rate concatenating individual loss experience and exogenous derived expected losses (Ai and Brockett, 2008). Two such rating schemes are prospective rating and retrospective experience rating (Casualty Actuarial Society, 1990), where the rate for a future period is determined using a weighted combination of expected losses (from some other source such as industry data) an individual experienced losses.

In addition to the above methods, a somewhat different method for individual risk rating is called schedule rating (Ai and Brockett, 2008). It adjusts the manual rates to reflect individual risk characteristics that may affect future losses. Unlike the above individual risk rating methods, however, it does not necessarily use individual loss experience to make this adjustment, but instead creates a factor to apply to the manual rate to account for characteristics known to affect the likelihood of losses (e.g., a certain building standard, such as height of first floor, may result in a multiplicative factor less than one being applied to the manual table rates for flood insurance) (Ai and Brockett, 2008).

CURRENT RATE-SETTING PRACTICES WITHIN THE NFIP

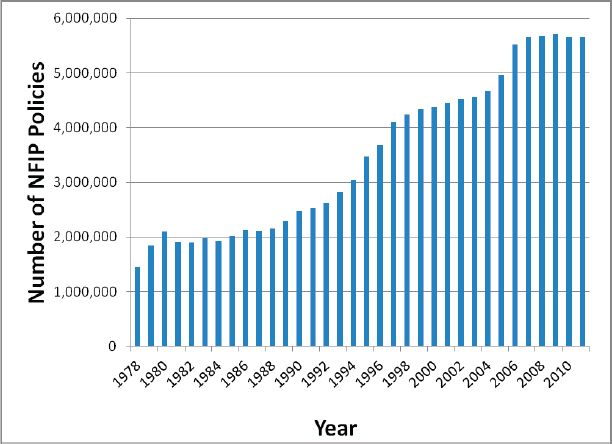

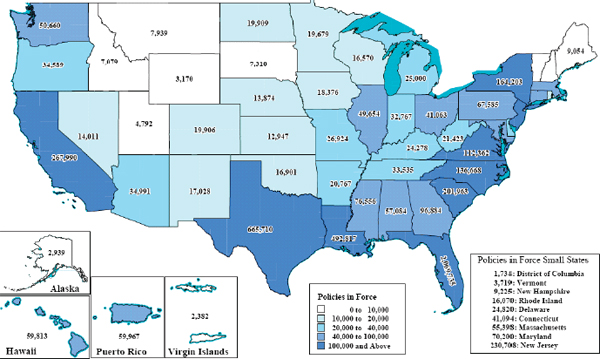

FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) has approximately 5.6 million policies insuring over a trillion dollars in assets. Currently, 21,881 communities participate in the NFIP.6 Broken down by structure type, this includes

_______________

5 The concept of credibility theory, which dates back to Mowbray (1914), is said to be “the casualty actuaries’ most important and enduring contribution to casualty actuarial science” (Rodermund, 1990).

6 As of June 2012.

• 3,839,254 single-family policies,

• 281,508 nonresidential (i.e., commercial) policies,

• 341,607 multifamily (non-condominium) policies,

• 1,123,427 units (in 78,821 contracts or buildings) Residential Condominium Building Association policies.

The above numbers include all NFIP policies regardless of flood zone designation and 10,361 properties that have been designated as severe repetitive loss properties7 (Andy Neal, FEMA, personal communication, July 19, 2012).

The purpose of this section is to explain the current process by which the NFIP sets rates and discuss the similarities and differences related to traditional private insurance processes for setting risk-based rates. Next, comments on the actuarial and fiscal soundness of the NFIP on the basis of the risk premium methodology used are presented. Finally, improvements and advancements that can be made to better serve the goals of the NFIP and the pricing of flood insurance are discussed.

Full-risk Class Rates

FEMA evaluates the flood risk of policy holders and determines rates for the “full-risk” class through a balance of elements including the extent and type of flood hazard, the base elevation of the insured structure and the structure type,8 the contents location (first floor, second flood, etc.), and whether or not the community participates in the Community Rating System9 that provides discounts for communities that actively manage their flood risk (Box 5-1).

At the core of FEMA’s risk-based rate setting is the calculation of the expected loss for a property. FEMA calculates community losses using average annualized loss data (Box 5-2). In theory, this is calculated for each property by conditioning upon the floodwater level and the probability of that level of water inundation occurring during the year. Thus, they assess the frequency or probability that the floodwaters will reach an elevation of i (which they denote by probability of elevation or PELVi). This number is then multiplied by the “loss severity” that would occur at the structure if the floodwaters reached level i (i.e., damage based on water depth in a given structure), which they denote by damage by elevation (DELVi). This is then summed over all possible water elevation levels to arrive at an expected loss.10

![]()

This is consistent with a standard actuarial method for calculating the expected loss due to flooding similar to the pure premium method described in equation (5-2) earlier. In practice, properties having similar risk-related covariates (flood risk elevation, construction type, zone, etc.) are grouped together, and a single rate is given to all properties in this class nationwide. This is essentially similar to risk-based rate setting by private insurers in property insurance and automobile insurance where entities having the same set of underwriting classification characteristics are grouped together and given the same rate. Risk pooling in this regard is also used by private insurers to spread the risk.11

_______________

7 Severe repetitive loss properties, as established in Section 1361A of the National Flood Insurance Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 4102a) is defined as a residential property that is covered under an NFIP insurance policy and has at least four claim payments and for which two of these payments in total have exceeded the market value of the property. See http://www.fema.gov/severe-repetitive-loss-program.

8 Condominium, single or multi-family home, residential or commercial use, number of floors, with or without a basement, ventilated crawlspace, etc.

9 The discounts given under the Community Rating System are modeled back in to the expected aggregate premium calculation for the NFIP by adjusting all premiums upward so that the aggregate premium collected is sufficient to cover expected losses accounting for CSR discounts for the CSR discounts. Thus, CRS discounts constitute a relative discount which is adjusted for in the aggregation and is not an uncompensated for diminution of income as occurs with other types of non-full-risk class policies. (Andy Neal, FEMA, personal communication, August 22, 2012).

10 See Hayes and Neal (2011, Appendix).

11 Although risk pooling is used in private insurance, there have been questions about the appropriateness of the breadth (nationwide) of NFIP’s grouping of all properties within the same zone classification for the purpose of obtaining a single rate applicable to all properties in the

BOX 5-1

FEMA’s Community Rating System

FEMA’s Community Rating System (CRS) is a voluntary incentive program that encourages floodplain management activities exceeding the minimum NFIP requirements. The CRS has 1,211 participating communities among the approximately 21,000 communities participating in the NFIP. However, policies held within CRS communities represent 68 percent of the policies in force (Bill Blanton, FEMA, personal communication, July 10, 2012).

Typically, communities receive between a 5 and 15 percent discount for participating in the program with a maximum discount of approximately 45 percent (FEMA, n.d.a; Bill Blanton, personal communication, July 10, 2012). Discounts are calculated based on a credit point system for actions that help save lives and property in the event of a flood—and that exceed the minimum NFIP requirements. There are four categories of activities that are credited: (1) public information programs that advise the public about the hazard, flood insurance, and strategies for reducing the hazard; (2) mapping and regulation programs that increase protection to development that postdates existing maps; (3) flood damage reduction programs, such as relocating or retrofitting vulnerable structures); and (4) flood preparedness programs, such as flood warning and dam and levee safety programs (FEMA, n.d.a). For additional insight regarding the CRS, see Chapter 7.

BOX 5-2

Average Annualized Flood Losses

Average annualized losses (AALs) due to flooding represent the estimated value of flood losses in any given year in a selected region. Analysis of such data provides information on changes in losses by geographic area that are useful in identifying loss trends and geographic anomalies in loss patterns. The data are also useful to leaders in establishing policies and priorities and developing flood risk management strategies.

FEMA’s Hazus-Multi Hazard (Hazus-MH) offers analysts the opportunity to quantify annualized flood losses in a given community over multiple flood recurrence intervals. The Hazus-MH program, which can calculate damages, casualties, and economic losses, is based on national data from U.S. government agencies. It may also use, when available, higher resolution data available within the communities. For flood AALs, it calculates losses under each of five flood recurrence intervals (10, 25, 1.0, 0.5, and 0.2 annual chance floods or 10, 50, 100, 200, and 500 years, respectively) and then multiplies the loss values by their respective annual frequencies of occurrence, then summing the values for an annual average. This approach is focused on the recurrence intervals within the bounds of FEMA FIRMs’ upper delineation, the 0.2 percent flood. Additional calculations using recurrence intervals for extreme events (>0.2 percent) would provide a more robust portrayal of the potential AALs but would likely increase the costs of the AAL process.

FEMA began the calculation AALs in 2009. Pilot data on flood AALs have been released for initial review within the floodplain management community but release of the entire report is awaiting final FEMA review. The use of Hazus-MH provides a relatively straightforward and simple but time-consuming method of making such calculations. Because the quality and resolution of the data used are subject to considerable variation across the country, the resultant AAL figures should be taken as general estimates and not high-resolution information. Such an approach is appropriate for the management uses envisioned by FEMA.

The determination of the components in the above expected-value calculation is as follows: The event frequency (probability) or PELV is obtained by reference to a collection of PELV probability curves created to describe the probability of various water depths relative to the 1 percent flood depth, that is, at this property the probability of a flood during the year reaching the height +2 (2 feet above the base flood level of the one percent annual chance flood) is a certain point on the PELV curve.12 The PELV curves provide probabilities up to the 0.2 percent annual chance event (flood recurrence interval of 1 in 500 years). For all flood events greater than the 0.2 percent level, the program assumes a “catastrophic” water depth level by doubling the 0.2 percent depth. Because of the low likelihood of this “catastrophic” water depth level and because of the generally small marginal increase in the damage assumption between the 0.2 percent water depth and the damage at the assumed catastrophic depth, this approximation does not affect the rate significantly. Currently, “residual risk” resulting from the likelihood of overtopping a levee, levee failure, human development resulting in other topographic changes affecting inundation probability, and so on are not mapped or considered in the PELV determinations (FEMA, 2006).

The second component in the above expected-value calculation, the damage estimate as a function of the water depth elevation, or DELV, is based on historical damage data obtained by FEMA associated with different water depths in the given zone, and varies with structure content and location. When the NFIP’s historical damage data are sufficiently credible13 based on the number of claims and the variability of those claims, the NFIP data are used to develop the statistical damage estimate. When historical NFIP data are absent, U.S. Army Corps of Engineering (USACE) data are used. When some historical NFIP data are available but are is not fully credible (in an actuarial sense), the NFIP program uses a blend of NFIP data and USACE data to determine the DELV variable. This is consistent with standard property and casualty actuarial practice in private insurance.14

Once the expected loss is determined, the actual premiums or rates for the NFIP are determined by “loading” the expected losses in a manner similar to equation (5-3). Specifically, the charged rate for the group charged at the full-risk costs is determined by the formula

![]()

where LADJ is the loss adjustment expense loading, similar to the factor k1 in equation (5-1), and DED is a factor that adjusts the DELV variable to compensate for the amount of the deductible chosen (so that the loss actually paid reflects the deductible amount) (Hayes and Neal, 2011). The variable UINS represents an adjustment to account for the underinsurance amount because not all properties can (or do) insure to their full value. The UINS factor is determined by the NFIP using a review of past insurance claims data. Incurred losses are a nonlinear function, with most losses being smaller and relatively fewer losses being much larger (i.e., the loss distribution is skewed); hence the variable UINS adjusts the loss for the percentage coverage to account for this nonlinearity (Hayes and Neal, 2011). This is similar to traditional homeowners insurance. Currently the value used for LADJ is 1.05 and

_______________

zone nationwide, without regard to state or topography. For example, the comparison of losses to premiums over time differs dramatically across states even within similar zones. This suggests that some properties in one state are cross-subsidizing other properties in other states because they are charged the same rate but have much different loss probabilities or risks (GAO, 2008). In a competitive insurance market with many participants, such cross-subsidization would be arbitraged away because an insurer who can identify those policyholders being overcharged relative to their risk (the subsidizers) would recruit such policyholders by offering lower premiums until perceived discrepancies disappear. Because the NFIP is essentially a monopolistic insurance provider, this cross-subsidization may continue to exist, and innovation to identify better pricing methods and cross-subsidization opportunities may not be pursued with the same vigor as in the private competitive market.

12 The curve for a given flood zone (A01-A30) is based on the difference between the 1 percent flood elevation and the 10 percent flood elevation with each policyholder being assigned a PELV curve. The original PELV curves are based on studies conducted at the time the program was established. FEMA is currently collecting data to reevaluate the original PELV curves (Andy Neal, FEMA, personal communication, November 7, 2011).

13 In actuarial practice “creditability theory” delineates when there is sufficient historical data to give a confident assessment of losses for estimation purposes, and how to augment the estimate of loss using auxiliary datasets when there are not sufficient historical data. See Casualty Actuarial Society (1990).

14 The accuracy of the loss data used for determining the values of DELV has been questioned since many entries in the NFIP data set obtained from claims history have loss values but are missing data on elevation at the site. In these cases NFIP uses a zero elevation in their calculation, which will bias the losses experienced at zero elevation, and distort the DELV curve values. See GAO (2008) for details and references to further studies validating this criticism.

the value used for DED is 0.98 (Andy Neal, FEMA, personal communication August 22, 2012). Finally, the factor EXLOSS represents the expected loss ratio and contingency loading15 and adjusts the rate to accommodate commissions, acquisition costs, and other costs such that the rate times the expected loss ratio is sufficient to cover the expected loss accounting for the loss adjustment expenses as well as the idiosyncratic choices by the purchaser of the deductible and underinsurance amount. Again, this formula is actuarially appropriate given the constraints and attributes of the program (absence of bankruptcy risk, ability to borrow from the government, etc.).

Discounted Rates

By statute, Congress mandated that the NFIP make flood insurance available to certain properties at less than their full-risk rates, that is, at discounted rates below those specified by equation (5-2). This occurs. for example. if (1) a structure was built before the flood insurance maps were available, that is, it was a “pre-FIRM” (Flood Insurance Rate Map) structure or built before December 31, 1974; (2) a structure was built in a V zone before 1981 and before maps that consider wave height were adopted in setting flood insurance rates; (3) a structure is in an AR or A99 zone for levees in the course of reconstruction or construction (so their current actuarial risk does not correspond to their current risk charge); or (4) the policyholder participates in a group flood insurance policy.

Discounts for structures that were built pre-FIRM or where the NFIP does not have any elevation information are by far the largest group—with 1,082,201 policies or a little less than 20 percent of policyholders. Only 7,508 policies are discounted because of entering the program prior to including wave height in rate setting, that is, pre-1981 V zones. Discounted rates are applied to approximately 24,907 policies for property owners behind levees in construction or deaccredited levees but where the community is showing a good-faith effort to construct levees or repair the levees (AR/A99).

Pre-FIRM Policies

The largest group of discounted policies consists of those that predate the existence of the flood insurance maps. By legislative directive, pre-FIRM policies were given a discount in order to encourage community participation in the NFIP, to help maintain property values for homeowners who might not have known of their flood risk at the time of purchase, and to encourage NFIP participation among those with a higher risk of floods (Michel-Kerjan, 2010). Currently, of the 5.6 million NFIP policies, there are 1,082,201 or approximately 19.3 percent of the policies that are pre-FIRM discounted policies (Andy Neal, FEMA, personal communication, July 19, 2012). These can be further decomposed as

• 736,066 single-family policies (150,674 of those are nonprincipal residences),

• 82,387 nonresidential policies (commercial) policies,

• 93,669 multifamily (non-condominium) policies, and

• 170,079 Residential Condominium Building Association policies (corresponding to 11,516 contracts or condominium buildings).

By statute, highly discounted premiums have been made available for pre-FIRM buildings in the Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA). Not all structures that were built in SFHAs prior to the FIRM are discounted, however, because some structures meet more stringent building codes and qualify for better rates on a full-risk basis because of elevation above the base flood level than they would receive taking the discount off the higher SFHA rate. For the discounted older buildings, the average full-risk premium is about five times greater than the average full-risk premium for compliant buildings. With the discounted premium level, the noncompliant NFIP discounted buildings only pay between 40 percent and 45 percent of what they should pay would they be charged using the actuarially determined full-risk premium for being in the SFHA. Even so, their discounted premiums are still much

_______________

15 Currently, the contingency loading incorporated into the EXLOSS factor includes a 10 percent additional load in nonvelocity zones and 20 percent in velocity zones (cf. Hayes and Neal, 2011).

higher than those that would be paid by actuarially rated policyholders for buildings constructed in compliance with the building codes.

The status of the pricing subsidies given to certain policyholders will change in the future. The Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 included provisions that were intended to help the fiscal soundness of the NFIP by eliminating certain pre-FIRM discounts and increasing the ability of the NFIP to raise rates to achieve fiscal soundness (Nechamen and Inderfurth, 2012). Effective July 1, 2012, pre-FIRM discounts are being removed from certain types of properties, with permissible increases in their flood insurance rates of up to 25 percent per year until the actuarial rate level is achieved for the property. Discounted policies losing their discount include nonprimary residences (e.g., second homes), severe repetitive loss properties,16 all business properties, homes that have had substantial damage or improvements (of over 30 percent of the market value of the property) after the implementation of the Act, and several other classes of properties (Nechamen and Inderfurth, 2012).

Group Flood Insurance Policies

A group flood insurance policy is a discounted policy offered after a presidentially declared flood event for property owners who qualify for federal individual assistance. Qualifications include low-income property owners who do not qualify for a Small Business Administration disaster loan. On a one-time basis, owners are provided by FEMA with a 3-year policy with a coverage amount equal to FEMA’s Individual and Households Assistance Program maximum (currently $31,400). The policy premium is set according to 44 CFR §61.17 at $600 per year, which is typically subtracted from the insurance adjustment payment received in the event of a loss (Andy Neal, FEMA, personal communication, January 15, 2013). Approximately 42,000 group flood policies were issued in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. These policies will eventually become nondiscounted and will be charged actuarial rates, and so they constitute a short-term imbalance, but new group flood insurance policies will be created as new floods occur (continuing to affect the fiscal soundness of the NFIP).

Grandfathered Rates

Grandfathered policy rates are applied to certain policies when revisions to FEMA’s FIRMs result in increased premiums. Unlike the discounts described above, grandfathering is achieved through cross-subsidies with other policyholders. Grandfathered rates are available to structures that were built in compliance with a particular map or to structures that purchased a policy prior to the revised map’s effective date, and whos purchasers have maintained continuous coverage since the map change. Grandfathering can apply to both the flood zone changes, resulting in zone grandfathering, and the one percent flood elevation changes, resulting in elevation grandfathering.

The most common form of zone grandfathering occurs when a policyholder was once outside the SFHA and paying a lower rate, but is now included in the SFHA because of to remapping. In this case, non-SFHA to SFHA zone grandfathered policies do not pay the lower preferred risk policy (PRP) non-SFHA rate. Instead they pay an average rate, called the X zone standard rate that is sufficient for the spread of risk for all non-SFHA to SFHA zone grandfathered structures. Effective October 1, 2010, FEMA introduced a 2-year PRP extension, allowing structures that were recently mapped into the SFHA to use PRP rates for a limited, 2-year period before moving to the higher X zone standard rate. This was achieved through a cross-subsidy by increasing the premium for all PRP policyholders. Approximately 90,000 PRP 2-year extension policies have been issued. There are approximately 1.6 million non-SFHA PRP policyholders (Andy Neal, FEMA, personal communication, August 9, 2012).

Zone grandfathering can also occur when a policy moves from a lower risk zone to a higher risk zone, for example, from an AE zone to a VE zone. In this case, the grandfathered structure pays the lower AE zone rate. Elevation grandfathering applies when new maps increase the elevation of mapped 1 percent flood without chang-

_______________

16 The Biggert-Waters Act defines severe repetitive loss properties as those that have “incurred flood-related damage (i) for which 4 or more separate claims payments have been made under flood insurance coverage under this title, with the amount of each claim exceeding $5,000, and with the cumulative amount of such claims payments exceeding $20,000; or (ii) for which at least 2 separate claims payments have been made under such coverage, with the cumulative amount of such claims exceeding the value of the insured structure.”

ing the zone. For example, a property that was 3 feet above the 1 percent flood elevation according to the previous FIRM and is now only 1 foot above the 1 percent flood elevation according to the revised FIRM would be eligible to use the +3-feet rate. FEMA is currently engaged in a study to quantify the number of zone and elevation grandfathered policies (Andy Neal, FEMA, personal communication, August 9, 2012).

The use of grandfathered rates does allow the grandfathered properties pay a lower rate than they would pay if the property were truly risk rated, and hence grandfathering implies that not all properties having the same NFIP premium are actually of the same risk level. This is a move away from risk-based pricing. Because properties receiving a higher risk classification under the Map Modernization program continue to receive insurance at the lower, pre-Map Modernization rate in spite of their now-recognized higher risk, the effect is similar to subsidization in that some properties are not charged their risk-based price, but rather the price that would have occurred if they had remained in their previous risk classification. Moreover, the grandfathered status continues indefinitely, even upon sale of the property (GAO, 2008).

Expected Annual Income from Premiums from the NFIP

To ensure an adequate aggregate expected annual income from premiums for the NFIP as a whole, the premiums are adjusted for the discounted risk classes. First, the aggregate expected full-risk premium anticipated to be received using the rating formula for the nondiscounted classes is calculated, the calculated base rates for the subsidized classes is added in, and then this value is subtracted from a calculated target “average historical loss year” value. The resulting difference is then used to determine an upward adjustment of rates among the discounted classes so as to accomplish a balance between the total anticipated income received and the targeted average historical loss year cost set by the NFIP. Note that by this process, some properties will be paying more than their actuarial rate.

There is a problem with this method, however. As noted by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) the"average historical loss year value is calculated using loss data over a limited loss experience time frame coupled with extreme loss values, such as the 2005 loss year (Box 5-3), which are heavily discounted when input into the historical loss year calculation (GAO, 2008).17 Thus, this historical loss year average value may balance the books in an historically typical year, but this value is neither a reasonable estimate of either actual historical average yearly losses (which now do include catastrophic loss years such as 2005), nor a reasonable long-term estimate of the actual expected future loss because it diminishes the impact of real or anticipated catastrophic loss events that have happened in the past and can be expected to happen again in the future.18The method used to calculate the average historical loss year ensures that in the long run there will be inadequate premiums collected to cover costs in significant flood years.19 Even with the mandate in the Biggert-Waters Act that catastrophic loss years be fully incorporated into the NFIP calculation of the “historical loss year average,” there is still a potential long-run shortage becausee larger but less frequent catastrophic floods (500-year floods, 1,000-year floods, etc.) may not have been recorded in the flood record at a particular location (although their likelihood might be modeled), yet these events might occur in the future. Hence, the historical average does not reflect the real expected long-term average loss.

NFIP’s Approach to Insurance Compared with Private Insurer Approaches

Insurance companies started to appear in the United States in the mid-1700s but did not expand rapidly, and encountered many bankruptcies at first. Early insurers were small, localized in geographic coverage, and usually

_______________

17 For example, since 2007 the catastrophic losses from the 2005 year were given only a 1 percent weight in the historical loss averaging process in “an attempt to reflect the events of 2005 without allowing them to overwhelm the pre-Katrina experience of the Program” (Hayes and Neal, 2011).

18 The full-risk class and the risk classes outside the 100-year flood level have premiums calculated using formula (5-2) and already incorporate the possibility of catastrophic risk.

19 FEMA itself recognized the inadequacy of using the mandated “historical average loss year” goal in premium setting even prior to the dramatic 2005 losses. From the NFIP’s 2004 Annual Rate Review, “[t]he underwriting experience period has, to date, included 7 heavy-loss years. Despite these heavy-loss years, the absence of extremely rare but very catastrophic loss years leads to the conclusion that the historical average is less than what can be expected over the long term” Hayes and Sabade (2004).

BOX 5-3

The 2005 Loss Year

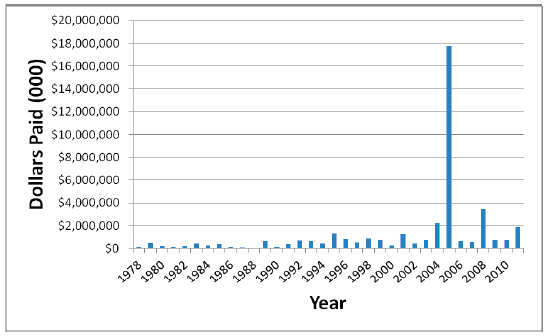

The record-breaking hurricane season of 2005 included five Category 4 and 5 hurricanes—Dennis, Emily, Katrina, Rita, and Wilma—that battered the Gulf Coast of the United States along with neighboring countries. In addition, the Los Angeles River experienced flooding in January 2005, and there was flooding in New England and the Mid-Atlantic during October 2005 caused by excessive rainfall due to a subtropical depression, Tropical Storm Tammy, and another tropical disturbance. The NFIP experienced an unprecedented amount of paid losses, 212,235 claims, totaling over $17 billion (Figure 5-1).

FIGURE 5-1 Loss dollars paid by the NFIP per calendar year.

SOURCE: http://www.fema.gov/policy-claim-statistics-flood-insurance/policy-claim-statistics-flood-insurance/policy-claim-13/loss.

specialized in a single type of insurance (e.g., fire insurance). Thus, initially, private localized insurers were reluctant to include flood coverage because of potential highly correlated losses and catastrophic total loss payment possibility (floods would simultaneously affect many of their customers, undermining the law of large numbers and central limit theorem for advantageous risk pooling) and because of the lack of ability to calculate appropriate actuarial rates that were protective of the insurer and at the same time affordable to the policyholder. Additionally, moral hazard and adverse selection considerations would imply that in a voluntary market the higher risk properties would disproportionately seek insurance and those that had insurance would be less motivated to take precautionary measures if they had insurance coverage. Nevertheless, in the late 1920s, there were still several dozen insurers willing to sell flood insurance, perhaps in part because USACE had declared in 1926 that improvements had been made to the levee system sufficient that they could now “prevent the destructive effects of floods” (Daniel, 1977; see also Moss, 1999; King, 2005).

The problems with private companies writing flood insurance policies were brought home dramatically by the great Mississippi River flood of 1927 and other riverine flooding in 1928, so that all of these several dozen insurers

stopped writing flood policies (King, 2005). Private flood insurance has been essentially unavailable in the United States for residential property since then (Browne and Halek 2010). The previously described ideal characteristics needed for a risk to be privately insurable are simply, to a large extent, missing in flood risk (Baranoff et al., 2009). According to William Hoyt and Walter Langbein in 1955, floods “are almost the only natural hazard not now insurable by the home—or factory owner, for the simple reason that the experience of private capital with flood insurance has been decidedly unhappy” (Moss, 1999).

The lack of availability of flood insurance did not stop floods from occurring, nor did it stop development in flood-prone areas.20 Such flooding motivated the federal government to provide aid to the victims as a humanitarian action. Over time the post-disaster aid moved increasingly away from being primarily provided by private charities (e.g., the Red Cross provided most of the relief in the 1927 Mississippi River flood) to a more central role for federal assistance (Moss, 1999). Indeed, the federal government has had an ever-increasing role in providing disaster relief after floods, and this increased involvement in after-the-fact emergency aid to disaster victims prompted Congress to investigate creation of a federal flood insurance program that could be considered as a form of preloss financing (Moss, 1999). Whereas private insurers feared the catastrophic and highly correlated nature of flood losses to local insurers, a federal program could spread risk nationwide and could make premiums more affordable by not charging (and reserving) for periodic very large disasters. Moreover, the federal government has the ability to mandate purchase, mitigating the adverse selection problem, and enforce building codes, mitigating some of the moral hazard problems. In 1968, Congress passed the National Flood Insurance Act21 with the goal of creating a preloss (insurance) financing arrangement that would lower post-loss disaster relief, encourage responsible development in floodplain areas, and encourage maintenance of flood control operations (e.g., levees).

Browne and Halek (2010) give a comprehensive review of the developments in the federal flood insurance marketplace since the passage of the 1968 law creating the NFIP. Moreover, the challenges reaching the original legislative goals of the NFIP and the various legislative flood insurance law changes enacted to address the shortcomings are detailed in other sections of this report. It remains true, however, that for the reasons previously stated, the private market for flood insurance is still problematic. Private flood insurance is primarily available to commercial businesses that can demand flood coverage as part of a larger insurance program that includes “all-risk” coverage.22 The NFIP remains the primary source of flood insurance for almost all homeowners and small businesses. However, there are a limited number of private insurance companies that offer flood insurance coverage for homeowners and small businesses as excess protection above the NFIP coverage limitations.

There have been many criticisms of the NFIP based on the perception that it does not operate like a private insurer, and impressions of how it should operate are based on notions of how private insurance operates. For this reason, and to set expectations of what is and is not possible for the NFIP in perspective, it is useful to compare the NFIP operation with those that occur in a private insurance setting. Toward this end, it is important to note that there are several ways in which the NFIP operates and prices risks that differentiate it from how a commercial insurer would price similar flood risks. These are in part due to the governmental nature of the NFIP which has different goals and constraints than private insurers, and these differences are briefly detailed below.

First, and importantly, commercial insurers must manage their capital reserves to ensure that they are able to honor their commitment to claims payable for policies in force at any one moment and to remain solvent for paying future claims. This is especially a challenge for any peril that has a potential for a major loss aggregation, of which flood is one of the greatest challenges. The private insurance industry is heavily regulated to ensure that policyholders can be confident that insurers will be able to honor claims made for the coverage they have purchased.

Commercial insurers also consider the time value of money and discount losses from the time of occurrence (Ti) to the time of premium payment using a discount function, V(Ti) that reflects their cost of capital, per equation (5-1). In the NFIP, the time value of money is not considered, and no adequately large contingency reserve has been set up to pay future claims because FEMA is backed by the U.S. Treasury Department should the premiums

_______________

20 Along this line, Moss (1999) quotes a congressional task force (U.S. Congress, 1966) as recognizing this problem when they observed “Floods are an act of God; flood damages result from acts of men.”

21 Public Law 90-448.

22 “All-risk” or “all-peril” policies cover any fiscal loss unless it is specifically excluded in the policy.

collected prove insufficient to pay claims. Indeed, if the NFIP had been able to set up a contingency reserve fund that grew large enough during noncatastrophic loss years to be able to fund the losses in catastrophic loss years, the “perceived excess” might be reclaimed and spent elsewhere in the federal budget. By contrast, private insurers must be self-sufficient and hence must consider the time value of money and the cost of capital and set up a reserve to forestall insolvency.23

Next, while the NFIP sets premium rates (for the full-risk class) sufficient to pay its own expected claims (including catastrophic claims), the classes of subsidized policyholders paying discounted prices makes no allowance for extreme nonhistorical-average-loss years in the premium calculation for the discounted classes. As noted above, the method used to calculate the average historical loss year for the NFIP ensures that in the long run there will be inadequate premiums collected to cover costs in significant flood years. A private insurer would not use this financially unsound, downwardly biased risk premium method without facing the extreme uncertainty of returns and danger of future insolvency.

Another difference between NFIP and a private insurer is that there is no profit factor loading in the formula for premium setting by FEMA. It can be argued that elimination of the profit loading factor might make sense for governmentally run programs because the objective function of a governmental program is different from that of a for-profit insurance firm. Additionally, NFIP does not need to compete in the capital markets to attract investor funds,24 and the issue of NFIP loss-induced insolvency and continued survival are not issues for the government-run program because of the financial backing of the government and its taxing authority. Moreover, neither is the profit or return on capital investment an objective of the government-run program, but rather the government has a societal welfare objective function (rather than a “profitability” objective function).

Since its formation the NFIP has had an objective of encouraging participation in the program, motivating community building standards, and making premiums affordable. Affordability of premiums has been and continues to be a prime concern of FEMA and is one important motivation for allowing discounts and subsidies in the program and for not adjusting premiums upward to reflect periodic catastrophic losses. To “load” the pure premium sufficiently to allow the NFIP to withstand reasonably anticipated, low-probability catastrophic losses (such as those in 2005 and worse) would require substantially elevated premiums. Setting aside such catastrophic contingency reserve capital, as would be necessary to endogenously withstand the financial consequences of catastrophic flooding, could undermine the societal welfare objective of encouraging community participation because premiums would necessarily rise, sometimes significantly, making some policyholders drop out of the market.

Moreover, given the parallel involvement of the government in flood disaster relief (separate from insurance), from a governmental perspective there is a natural trade-off between insurance pricing and disaster relief costs. Either way, the government pays (Czajkowski et al., 2012). Suppressing current insurance premiums and not allowing the buildup of large contingency reserves for future claims payments will lower current premium costs, encourage participation in the NFIP, and reduce the amount of disaster relief needed from the government after a flood. On the other hand, such a strategy of suppressed rate setting runs the inevitable consequence of periodic subsidization of the NFIP in catastrophic loss years. This is another issue that makes the NFIP rate-setting methodology differ from private insurers’ rate-setting methodology, in part due to the governmental backing and differing objective function.

Further compounding the issue, the dual role of the government in providing both flood insurance and flood disaster relief (even to those who did not purchase insurance) presents what Browne and Hoyt (2000) refer to as “charity hazard” wherein the individual does not have the motivation to take proactive steps (such as risk financing or insurance purchase) when they believe that after an event they can depend on the charity of others (the government, charitable organizations such as the Red Cross, etc.). Although in truth the amount of money received by

_______________

23 Under provisions of the Biggert-Waters Act, FEMA is to establish a National Flood Insurance Reserve Fund that contains at least 1 percent of the total potential loss exposure funded by putting in 7.5 percent of the required amount each year until fully funded (Nechamen and Inderfurth, 2012). A reserve level of 1 percent of expected annual losses would still not be considered prudent in private insurance.

24 It could be cogently argued that the requirement that the NFIP pay back with interest the U.S. Treasury for the funds borrowed after the catastrophic 2005 loss year implies that they do indeed have a cost of capital. Interest rates on this debt are now relatively low (0.25 percent) but have been as high as 4.875 percent (Hayes and Neal, 2011).

the flood victim is much larger and more rapidly delivered with flood insurance, the perception of many is that if a flood occurs, the government will fully compensate victims.

Arguing in favor of building a catastrophic contingency reserve and/or putting a profit loading factor into the rating formula is the reality that, although FEMA was able to borrow money from the U.S. Treasury to finance the losses experienced by the NFIP in the catastrophic loss year 2005, the program is now being required to repay this “loan” back to the Treasury with interest. This directive could mean raising premium levels on new and current policyholders to pay back the loan and interest, which is again contrary to the objective function of the NFIP to encourage participation and make premiums affordable. Moreover, should interest rates rise from their current very low levels, it may be unlikely for NFIP (i.e., policyholders) to pay the interest on the loans from current revenue.

Actuarial Soundness Versus Fiscal Soundness of the NFIP

There has been much discussion concerning the actuarial soundness of the NFIP since the NFIP is required by law to promulgate rates that have actuarial soundness (Mathewson 2011). Some, such as the GAO (2008), specifically state that “[t]he program is not actuarially sound.” Even actuaries at the NFIP (Hayes and Neal, 2011) state: “Because the NFIP, as explained above, charges highly discounted premiums for many older buildings, it is currently impractical for the NFIP to be actuarially sound in the aggregate.” The notion of actuarial soundness in the context of the NFIP, however, is somewhat subtle and elusive because of the differences described previously between a government-run program with mandated discounts, no profit requirement, no significant interest income, and reliable, significant borrowing power and the private sector from which the notions of actuarial soundness arose and are routinely applied.25

Indeed, even within the private insurance market, a precise definition of “actuarial soundness” in the Property and Casualty Insurance industry could not be found by the Actuarial Soundness Task Force of the American Academy of Actuaries,26 although hints at what might be meant can be gleaned from the use of the term in the context of actuarial statements of principles. These principles include the following:

1. an actuarial rate should reflect the expected value of the insured risk;

2. a rate should be an estimate of the expected value of future costs, accounting for all costs associated with the transfer of risk;

3. a rate should provide for the costs associated with an individual risk transfer; and

4. the rate should be reasonable and not be excessive, inadequate, nor unfairly discriminatory (Mathewson, 2011).

These principles imply, in particular, that revenues collected should be sufficient to pay future losses for the class from whom premiums were collected. Moreover, the rates charged should be determined in such a manner as to be reasonable, and be calculated in a statistically valid manner reflecting the expectation of future loss costs for the classes used as groups for pooled risk underwritten. In the context of private insurers, these statements make good sense, especially since insurance is a future performance-contingent claims contract, with governmental regulations directed especially toward ensuring the ability of the private insurer to remain solvent and pay future claims. This is much less of (or perhaps not even) a consideration in the governmentally backed NFIP where the ultimate payment of the claims is not in question, profit is not a motive, and other objectives dominate.

To achieve actuarial soundness, predictability, and affordable rates, private insurers use risk pooling (over either policyholders such as occurs in automobile insurance or commercial general liability insurance, over space as occurs in property insurance, or over time such as occurs in life insurance, or some combination of these techniques) to hedge, spread, diversify, or pool risk so that in the aggregate the premiums collected would be sufficient to pay

_______________

25 The NFIP can collect interest when there is a surplus in the fund, but its borrowing authority is legislatively set and was significantly raised in the wake of hurricanes Katrina and Sandy.

26 “Unlike the Health actuarial practice …, the Actuarial Standards of Practice applicable to property/casualty practice do not directly define the term actuarially sound or actuarial soundness” (American Academy of Actuaries, 2012).

expected losses. The NFIP on the other hand operates as a governmental entity in a more political environment. One result of this more political influence is that the NFIP does not adopt any of these approaches. The program does not adopt risk pooling across properties (as some are offered discounted rates and the lost discount dollars are not recovered from other policyholders in the risk pool), and risk is not pooled over time because no sufficient reserve fund is set up using surplus in 1 year to compensate for losses in a subsequent year.27

Dictated by legislation, the NFIP created a dual system of rate promulgation that is not adequately pooled over time, space, or policyholder. The NFIP has essentially a rate classification methodology created by statute that creates a “full-risk” rate class (consisting of about 80 percent of the policies) that are charged risk-based (or actuarial) premiums and a “discounted risk” class (about 20 percent of the NFIP policies). Because the discounted policies are charged premiums that are lower than their expected losses and expenses, and because the difference between the full-risk premium for a discounted policy is simply revenue lost to the NFIP (i.e., this lost revenue is not compensated for in any other part of the premium structure), the NFIP is, by legislated mandate, fiscally unsound in the long run. Congress could have appropriated funds to compensate FEMA for the lost revenue dictated by the statutory discounts, and had they done so, the NFIP would be in a stronger fiscal condition.

The statements of actuarial principles do allow actuaries to use differing models with different assumptions, provided they can be reasonably justified and estimate future loss costs in a defensible manner, so the notion of actuarial soundness in the context of legislatively mandated discounts can be defended in a governmental context apart from strict fiscal soundness that is appropriate for private insurers. For catastrophic governmental insurance programs, such as the NFIP, the California Earthquake Authority (CEA), the Texas Windstorm Insurance Association, and others, there are additional mitigating considerations concerning the adequacy of rates since, in the event of insufficient funding via the premium collection mechanism, the program may have recourse to alternative funding mechanisms (e.g., borrowing from the U.S. Treasury or taxpayers in the case of the NFIP). As stated in the Special Report on Actuarial Soundness (American Academy of Actuaries, 2012),

While not all publicly based catastrophe programs rely on outside sources of funding (e.g., taxpayer dollars or assessing a broader policy base), when they do, additional examination is needed to evaluate actuarial soundness.

For example, the setting of discounted rates so as to make the entire NFIP system able to obtain sufficient income that the premiums collected are sufficient to cover the “average historical loss year” value described previously can be construed as a form of directed actuarial soundness appropriate for this government program with significant borrowing power and mandated discounted rate classes. It will not, however, be financially sound, nor was it ever intended to be.

An additional consideration that must be added to general actuarially sound rate-setting principles is that the rates must be set consistent with the law. Even if one class of insureds has a documented higher expected loss cost than another, if the law specifies that the insurance company handle their premium rate setting in a specific manner, then the insurer’s rates may not be able to legally reflect these expected loss cost differences. The rates obtained following legal dictates and not using this class variable, and the resulting cross-subsidy (mandated by law) would not generally be construed as making the new rates actuarially unsound even as they could result in cross-subsidies and not strictly risk-based premiums. For example, 60-70 years ago, African American males were charged higher rates for life insurance because of having (actuarially or statistically verified) lower life expectancy than white males. This process was legally outlawed in the 1960s, but this does not mean that life insurance premium rates that now follow the dictates of the law and ignore race are actuarially unsound. Overall prices are adjusted so that the entire book of business is balanced, and this is acceptable actuarially.

Thus, the concept of actuarial soundness must be contextualized in the framework of the laws restricting how rates may be set. A system may be fiscally unsound because of the inability of the actuaries to charge rates that reflect risk in an appropriate manner, but this is different from being actuarially unsound. This is relevant when

_______________

27 Private insurers that write flood risk coverage for commercial clients often use reinsurance contracts to spread the risk, or use catastrophe derivatives available in the capital markets to hedge the financial impact of flood risk. However, the NFIP does not use reinsurance or capital markets to hedge flood risk.

discussing the actuarial soundness of the NFIP because, as the Special Report on Actuarial Soundness (American Academy of Actuaries, 2012) states:

State and national catastrophe insurance programs present additional points of discussion regarding what constitutes actuarially sound cost estimates or rates. Rates may be, by design, subsidized. The programs are generally not designed to generate a profit, and large losses may be funded by alternative mechanisms.

Indeed, in the case of the NFIP, legal constraints on the premiums that can be charged to certain groups of policyholders constitute an economic externality on the cash flow such that the program’s financial viability would be threatened were it to rely solely on its own generated premium income. Financial soundness and actuarially soundness are coincident in private insurers, but they need not be in governmental insurance programs. In private insurance when regulations on pricing suppress prices so as to constrain the insurer to charge insufficient rates, they have the option to drop out of the market and stop writing business.28 The NFIP and other governmental programs cannot make this decision on their own. Thus, the NFIP uses a general rate-setting formula given by equation (5-3) that is consistent with standard actuarial models such as equation (5-1), calculates this rate for all properties, but can legally only apply it to the full-risk class. A form of overall balance is targeted via an adjustment of the discounted rates to obtain funding for the average historical loss year discussed previously.

For estimation and actual rate-setting purposes, insured properties are cross-classified according to a smaller but fixed number of characteristics, grouped into a smaller number of hazard zones and property attributes (with basement, multiple story, etc.), and a common nationwide rate determined for each class. According to Hayes and Neal (2011), “[t]here are 30 numbered A Zones for which different sets of PELV values may be assigned.” However, the risk zones are combined for rating purposes. Combining exposure units according to common underwriting characteristics for rating purposes is an actuarially sound manner for setting premiums, consistent with methodology used in other insurance settings (although there is always the question concerning oversimplification involved in having too few risk classes and consequently too heterogeneous exposure units within a given class, creating induced inequities in premiums). In the case of the NFIP today it is argued that improved and more accurate graduated risk-based premiums could be achieved by further improving estimates of inundation level probabilities (using improved maps or hydrologic studies, incorporating residual risk into the probability of inundation of a property behind a levee, etc.), and that improved estimates of the severity of the loss accuracy may be obtained using Lidar data (or something similar) to obtain better estimates of structure elevation and damage characteristics (Chapter 3). However, these are improvements to an already actuarially sound rating method.

The major structural drawback to the fiscal soundness of the NFIP is not actuarial unsoundness due to inappropriate or inadequate rate-setting methodology or inadequacies in using a formula such as equation (5-4), but rather the fiscal unsoundness caused by not being able to apply equation (5-4) uniformly across all classes. The NFIP-mandated “discounted risk” class was anticipated to eventually decrease substantially over time, and this has indeed been the case. Still, there are a substantial number of discounted policies in the NFIP, approximately 20 percent of the 5.6 million policies. The difference between the full-risk premium for a discounted policy and the discounted premium for the policy is revenue lost to the NFIP (this lost revenue is not compensated for in any other part of the premium structure). FEMA is legally unable to raise premiums in a manner sufficient to allow the NFIP to be financially sound or to build a contingency reserve fund sufficient to pay for a catastrophic future loss. Without this ability, the NFIP is destined by law (not by actuarial methodological inadequacy) to run short of money in the long run, with occasional dramatic shortfalls (such as occurred in 2005). Furthermore, repetitive loss properties continue to drain the fiscal soundness of the NFIP.29

_______________

28 Examples include restrictions on rates in high-risk coastal areas in Texas and Florida that drove insurers from the market, or in automobile insurance in Massachusetts when it was very heavily regulated.

29 A 1995 Senate Task Force Report, Federal Disaster Assistance: Report of the Senate Task Force on Funding Disaster Relief, noted that in 1993 repetitive loss properties accounted for 2 percent of the properties covered by flood insurance but accounted for 53 percent of the claims filed and 47 percent of the dollars paid from the Flood Insurance Fund (Moss, 1999).

The NFIP is constructed using an actuarially sound formulaic approach for the full-risk classes of policies, but is financially unsound in the aggregate because of constraints (i.e. legislative mandates) that go beyond actuarial considerations. Parts of the Biggert-Waters Act that relate to adjustment of fiscal practices, discussed above, move the program toward a financially sounder approach.

Improving the NFIP Rate-Setting Process: Incorporating Technological Improvements to Better Obtain Risk-Based Premium Structures

While the mathematical construction used by the NFIP in determining their risk rates is based on actuarially sound principles as applicable to a government program, these processes and procedures could still be enhanced and aligned with a more rigorous and risk-based methodology by using finer graduation of risk propensity at the individual policyholder’s structure level. Although the NFIP currently uses a small number of zones for nationwide pricing purposes, the suggested finer graduation would not be foreign to the NFIP. According to GAO (2008):

NFIP implemented the nationwide class-rating system because of the nature of the program and the desire to make it less complex and easier for agents and customers to understand. In the early years of the program, rates were set on a community-by-community basis. But as the number of communities participating grew, this system became unwieldy and costly to maintain.

The complexity, costliness, and unwieldiness referred to above have been alleviated by technological and computer advancees that could allow agents and customers to interactively obtain structure-specific premium quotes online in real time. Additionally, existing advances in meteorologic and geotechnical modeling can allow the underwriter to model the likelihood and severity of flood damage individually so the complexity of the calculation or the number of zones is no longer a compelling factor at the agent or customer level. These advancements were not available in the 1960s when the core structure of the risk-based pricing framework was originally developed but can be utilized now to improve the system.

Although the general form of the rates given in equation (5-3) is actuarially based, in practice the implementation using a small number of zone categories and homogeneity of premiums within any given zone across the entire nation ignores differences within contiguous zone properties and makes the premium determination cruder and less directly risk-based than they need to be given today’s knowledge and technology. Currently, the following zone categories are used:30

1. coastal, V Zone, within the 100-year flood frequency zone and subject to wave action or velocity-induced damage;

2. inland, A Zone, within the 100-year flood frequency zone but not subject to wave action or velocity-induced damage; and

3. all other, X Zone, which includes other flood zones and those outside identified 100-year flood zones (considered to be of low or moderate flood risk).

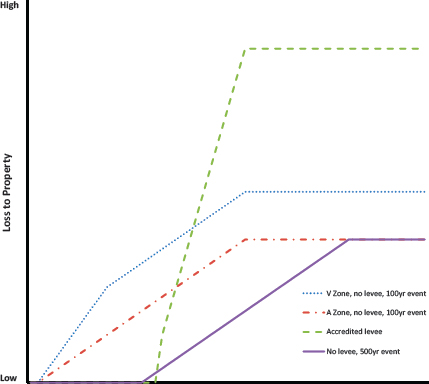

Properties that are located behind levees are placed in one of the last two categories. If the levee is accredited by FEMA to the one percent annual chance flood level, the “all other” or X zone category is applied. If not, the property is considered in the category that would apply without the levee being there. It can be argued that this approach to properties behind levees is appropriate based on the size of flood needed to create damage (over the one percent annual chance flood level). However, when viewed from a risk assessment perspective, it is apparent that the range of potential scenarios behind a levee and the loss corresponding to properties behind 100-year levees is very different from the loss that occurs from floods on the adjacent natural floodplain above the 100-year flood level (Figure 5-2).

_______________

30 There is also a preferred risk policy available to properties in lower-risk areas with a minimal loss history.

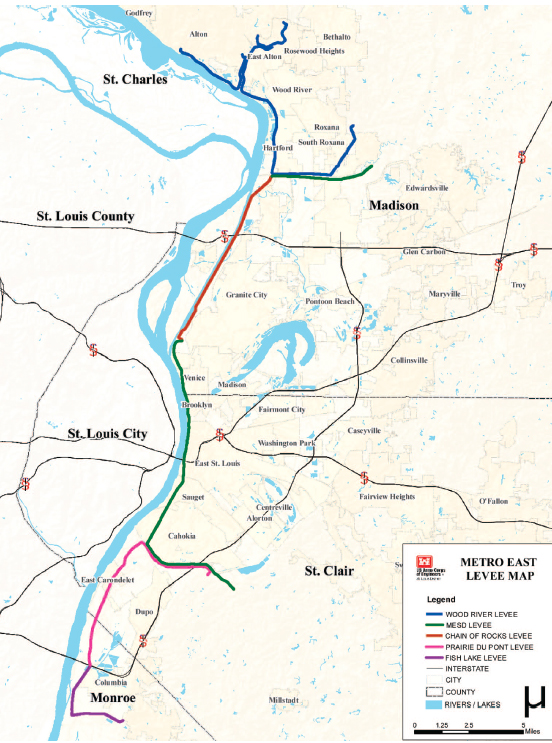

FIGURE 5-2 Notional schematic illustrating the damageability (or vulnerability) curves associated with example properties. The properties in the 100-year zone are prone to initial damage more frequently (the V Zone has increased damage due to wave action which has the potential to cause structural damage). The property in the 500-year zone does not experience loss as frequently, but the impact of flooding results in a similar profile of loss as the water depth increases. The property behind the levee has the advantage of no damage until the levee is overtopped or fails (similar to a property located outside the 100-year flood zone). However, once the water depth increases above the 100-year level, the potential loss to properties could be far more severe than if the levee was not there, and certainly more severe than that to properties located at elevations above the 100-year flood level. This is due to the fact that when the levee is overtaxed, water flow is likely to be rapid (similar to the coastal V zone) and the water level may be significantly deeper if the area behind the levee is at a low elevation compared with the levee.