Approaches to Physical Activity in Schools

Key Messages

• Data are insufficient to permit assessment of opportunities for and participation in sedentary activities in schools.

• Schools need to strive to reduce unnecessary opportunities for sedentary behavior.

• When embracing the advantages of technology for learning, schools need to be aware of its negative impact on students’ physical activity behavior.

• Recess has been shown to be beneficial for academic achievement. It is counterproductive to withhold recess or replace it with classroom activities as a punishment.

• Several models and examples demonstrate that scheduling multiple daily recess periods during the school day is feasible.

• School-based sports and active transport provide opportunities for physical activity but may not be accessible or attractive for all youth.

These opportunities need to be reexamined to address disparities based on socioeconomic status, school location and resources, students’ disabilities, or cultural/religious barriers.

• Participation in intra- and extramural sports has flourished over the past 40 years; however, school systems need to ensure that equitable sports opportunities are available for youth in all types of school settings and at all levels of socioeconomic status.

• Nonsport after-school programs should include physical activity.

• Active transport to and from school can be a safe and effective way to increase students’ daily physical activity, especially where a large proportion of students live close to their school.

• Each community needs to examine systematically opportunities for community-based promotion of physical activity.

• Inviting students’ families and other community members to participate in developing before- and after-school programs, including sports and active transport, will increase program sustainability.

It has been argued that, while reversing the obesity epidemic is not solely the responsibility of schools, the trend is unlikely to change without schools’ assistance (Siedentop, 2009). Schools are an ideal venue for the implementation of healthy behaviors because they serve more than 56 million youth in the United States; because youth spend such a large amount of time in school; and because schools already have the access, personnel, equipment, and space to implement physical activity programming.

Physical activity opportunities in schools take the form primarily of formal instruction in physical education for all students and sport-based athletics for the talented and interested. Although physical education is a required school subject, the classes may occur infrequently, and children taking them often accrue only low levels of physical activity (Simons-Morton et al., 1994). According to Tudor-Locke and colleagues (2006), physical education programs typically provide only 8-11 percent of a student’s daily recommended physical activity. However, a meta-analysis of the literature revealed that physical education can help children achieve up to 40 percent of the recommended 60 or more minutes of daily vigorous- or

moderate-intensity physical activity per day (Bassett et al., 2013; see also Chapter 5).

Mahar (2011) states that children’s physical activity levels are directly related to the opportunities they have to be active. Schools have the potential to influence the physical activity behaviors of their students through various opportunities in addition to physical education (e.g., recess periods, classroom physical activity breaks, active transport to and from school; van Landeghem, 2003). Furthermore, children are sedentary for much of the school day, and emerging evidence suggests that long periods of inactivity should be avoided. Thus it is essential for the school setting to provide opportunities outside of physical education for school-age children to be physically activity throughout the school day.

This chapter reviews the status and trends of sedentary behavior in schools and describes opportunities for physical activity in the school environment other than physical education, including classroom activity Breaks, recess, intra- and extramural sports, active transport, and after-school programs. Also reviewed are policies that may affect these opportunities, as well as barriers to and enablers of the opportunities. Chapter 7 examines the evidence on the effectiveness of these physical activity opportunities.

The committee did not identify a widely recognized definition of sedentarism, a new word in the English language, but one that exists in other languages to describe sedentary behaviors, sedentary activities, a sedentary lifestyle, or physical inactivity. Bernstein and colleagues (1999) describe sedentarism in terms of energy expenditure, while Ricciardi (2005) defines it in terms of what it is not, that is, not engaging in physical activity. Probably the most commonly accepted definition is time spent other than in sleep, or time spent in vigorous-, moderate-, or light-intensity physical activity. The word also is used to describe the status of a person or a population with high levels of sedentary behaviors or a sedentary lifestyle.

Sedentarism can be categorized as (1) recreational sedentarism, which refers mainly to media use or “screen time” but can also include more traditional sedentary activities such as recreational reading or having a conversation while sitting, and (2) nonrecreational sedentarism, which refers to schoolwork or other types of work that occur while sitting and also to other sedentary activities that are necessary to perform daily tasks, such as motorized transportation or eating a meal. Most of the public health interest in sedentarism has focused on decreasing recreational sedentarism, especially screen time, but there is increasing interest in ways to alter sedentary work so it can be performed while engaging in light physical activity or even while standing. Standing desks and treadmill desks are becoming popular

for adults in the workplace, for example, and many schools are seeking creative ways to integrate light physical activity into traditionally sedentary schoolwork. Such efforts are important given the amount of sedentary time entailed in schoolwork. In Australia, for example, 42 percent of nonscreen sedentary time is school related (Olds et al., 2010).

Such efforts to address nonrecreational sedentarism are just emerging, and much research and innovation are needed to move these efforts forward. On the other hand, significant research already exists on decreasing recreational sedentarism, especially among children, to treat or prevent obesity. Today, 46 percent of U.S. children aged 6-11 fail to meet the recommendation of less than 2 hours of recreational sedentarism (screen time) per day (Fakhouri et al., 2013). In addition to the nonrecreational sedentarism that occurs while children sit to perform schoolwork, significant recreational sedentarism takes place on the way to school and in school during breaks, recess, lunch, and after-school programs. Data are not available on the extent to which recreational sedentarism occurs on school grounds and on whether recreational sedentarism in school should be an important public health target as it already is outside of school. What is known, however, is that “eight- to eighteen-year-olds spend more time with media than in any other activity besides (maybe) sleeping—an average of more than 7½ hours a day, seven days a week” (Rideout et al., 2010, p. 1).

One of the lessons of pediatric obesity research is that behavioral approaches designed to increase physical activity are different from those designed to decrease recreational sedentarism and have different effects on behavior and health. Using behavioral economic theory, Epstein and colleagues (1995) demonstrated that monitoring children and encouraging them to decrease recreational sedentarism was more successful in treating obesity than either promoting physical activity or targeting both physical activity and sedentarism at the same time. Furthermore, the children randomized to the intervention targeting only sedentarism increased their enjoyment of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, while enjoyment of moderate-intensity physical activity decreased among those randomized to physical activity promotion; changes in enjoyment among those in the combined intervention group were between those in the other two groups. The importance of targeting a decrease in sedentarism was further highlighted when Robinson (1999) published the first successful school-based obesity prevention intervention that targeted only sedentarism, with no behavioral intervention focused on physical activity promotion or dietary changes. Since then, several randomized trials have confirmed the causal link between recreational sedentarism and childhood obesity (Tremblay et al., 2011). Despite this evidence, however, the approach of specifically targeting sedentarism has received only limited attention. While academic research has focused on using school as a setting in which to teach

students how to decrease sedentarism outside of school, this approach has not translated into widespread policies or curricula. Such efforts may be particularly important as sedentarism appears to track among individuals from childhood to adulthood (Gordon-Larsen et al., 2004; Nelson et al., 2006).

Of interest, a large nationally representative survey found that, “contrary to the public perception that media use displaces physical activity, those young people who are the heaviest media users report spending similar amounts of time exercising or being physically active as other young people their age who are not heavy media users” (Rideout et al., 2010, p. 12). The question was, “Thinking just about yesterday, how much time did you spend being physically active or exercising, such as playing sports, working out, dancing, running, or another activity?” This finding suggests that media use does not displace vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity but more likely displaces light-intensity physical activity, schoolwork, and sleep. Light-intensity physical activity, including playing or even just standing, is more difficult to measure than vigorous-or moderate-intensity physical activity, but its positive health impact is increasingly being recognized (see Box 2-4 in Chapter 2). The finding of this survey also suggests that promotion of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity may not decrease sedentarism but rather might replace light-intensity physical activity. Therefore, the optimal way to promote an overall increase in physical activity (including light-intensity physical activity) may be to use behavioral approaches to decrease sedentarism, as has been shown in behavioral research (Epstein et al., 1995; Robinson, 1999).

One of the challenges to monitoring sedentarism is the fact that children and adolescents frequently multitask. As noted earlier, Rideout and colleagues (2010) found that U.S. youth aged 8-18 spent more than 7.5 hours per day using recreational media; 29 percent of this time was spent multitasking, resulting in a total media exposure of almost 10.5 hours per day. This figure represents an overall increase in sedentarism since 1999, when the corresponding figures were 6.2 hours and 7.3 hours per day, respectively. Television content still dominated sedentary time, accounting for 4.3 hours per day. Computer use for schoolwork (not included in these totals) averaged 16 minutes, while computer use for recreational purposes totaled 1.3 hours per day. On a typical day, 70 percent of youth went online for any purpose, including 57 percent at home, 20 percent at school, and 14 percent elsewhere. It is unknown whether all online activities at school were related to schoolwork.

In addition to displacing physical activity and schoolwork, recreational media use exposes youth to “a constant stream of messages” that shape their perception of what is normative, including food choices, physical appearance, physical activity, and even sedentarism itself (Rideout et al.,

2010). Usually, these perceived norms are not in line with healthy or academically productive behaviors, and cannot be countered by the best efforts of parents and teachers. As a consequence, compared with those who used recreational media the least, “heavy users” tended to have lower school grades and to report that they were getting in trouble “a lot,” unhappy, sad, or bored (Rideout et al., 2010). Furthermore, in the face of rapidly advancing technology, parents and teachers are not always fully aware of the many ways in which media and marketing are part of youth’s lives. In addition to television and desktop computers, laptops, tablets, and cell phones often follow children and adolescents into the school bus, class, recess, and after-school activities unless such access is limited by policy, providing increasing opportunities to be sedentary on school grounds. In 2009 an average of 20 percent of media consumption, more than 2 hours per day, occurred with mobile devices, some of this media use likely occurring on school grounds. This figure probably has increased since then. Rideout and colleagues also note that children whose parents make an effort to limit media use spend less time consuming media, but whether this holds true for limits on recreational sedentarism in the school setting is unknown.

Both recreational and nonrecreational sedentarism in schools need to be monitored separately from physical activity. Specific school policies, based on updated knowledge of media use, need to focus on decreasing recreational sedentarism in school and integrating prevention of recreational sedentarism outside of school into the education curriculum. Because media use among youth already is significantly higher than recommended, schools should not provide students with increased opportunities for sedentarism, such as television sets in classrooms, the cafeteria, or after-school programs; access to social networks and recreational media on school computers; or the ability to use cell phones anywhere and at any time on school grounds or school transportation.

Research is needed to explore sedentarism and media use in schools more systematically so that evidence-based school policies to decrease these behaviors can be implemented to increase overall, including light-intensity, physical activity. In particular, surveys of media use are needed to document the amount of recreational sedentarism taking place in the school setting, where, in contrast with the home setting, public health policy can potentially be implemented.

OPPORTUNITIES TO INCREASE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN THE SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT

School physical activity programs are needed so that schools can ensure they are providing students with 60 minutes or more of vigorous-

or moderate-intensity physical activity per day. Physical activity programs are neither equivalent to nor a substitute for physical education, and both can contribute meaningfully to the development of healthy, active children (NASPE and AHA, 2012). The former are behavioral programs, whereas the latter are instructional programs. Box 6-1 presents the Healthy People 2020 objectives for non–physical education physical activity opportunities in school settings.

The following sections describe various non–physical education opportunities for physical activity in the school environment. The discussion includes relevant policies, barriers, and enablers.

BOX 6-1

Healthy People 2020 Objectives for Non– Physical Education Physical Activity Opportunities in School Settings

• Increase the number of States that require regularly scheduled elementary school recess.

• Increase the proportion of school districts that require regularly scheduled elementary school recess.

• Increase the proportion of school districts that require or recommend elementary school recess for an appropriate period of time.

• Increase the proportion of the Nation’s public and private schools that provide access to their physical activity spaces and facilities for all persons outside of normal school hours (that is, before and after the school day, on weekends, and during summer and other vacations).

• Increase the proportion of trips of 1 mile or less made to school by walking by children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years.

• Increase the proportion of trips of 2 miles or less made to school by bicycling by children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years.

SOURCE: HHS, 2012.

Classroom Activity breaks

An emerging strategy for increasing daily participation in physical activity in schools is the implementation of structured, classroom-based physical activity breaks. Classroom physical activity includes all activity regardless of intensity performed in the classroom during normal classroom time. It includes activity during academic classroom instruction as well as breaks from instruction specifically designed for physical activity. It also includes time spent learning special topics (e.g., art, music) even if not taught by the usual classroom teacher. It excludes physical education and recess even if conducted in the classroom by the usual classroom teacher. It also excludes physical activity breaks during lunchtime. Although some discussions of schooltime activity breaks include such breaks during lunchtime (Turner and Chaloupka, 2012), the committee views lunchtime physical activity as more akin to activity during recess and before and after school than to physical activity during normal academic classroom time. While a number of programs specifically designed to increase the volume of students’ physical activity during usual classroom time exist, the committee found no information about changes in such programs over time at the population level.

A typical break consists of 10-15 minutes focused on vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. This strategy has been found to be effective in significantly increasing physical activity levels of school-age children (Ernst and Pangrazi, 1999; Scruggs et al., 2003; Mahar et al., 2006). Bassett and colleagues (2013) found that classroom activity breaks provide school-age children with up to 19 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, and the sustained use of such breaks was shown to decrease body mass index (BMI) in students over a period of 2 years (Donnelly et al., 2009). The effectiveness of classroom physical activity breaks is discussed further in Chapter 7.

An example of an effective school-based physical activity program is Take 10! Kibbe and colleagues (2011) provide consistent evidence that the Take 10! program has been effective in increasing physical activity levels among a variety of samples of children enrolled in kindergarten through 5th grade in various countries. Likewise, Mahar and colleagues (2006) found that, with the implementation of 10-minute physical activity breaks called “Energizers,” students increased their time on task while averaging approximately 782 more steps in a day. Another example, supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center to Prevent Childhood Obesity (2012), is Jammin’ Minute, a realistic and effective “bridge” tool for increasing children’s physical activity until schools have sufficient resources to develop more comprehensive physical education programs. Jammin’ Minute has important implications for advocates and policy makers, as well

as administrators and teachers, seeking ways to make school environments healthier for children. At the same time, it should be emphasized that, while the benefits of small increases in physical activity during the school day need to be recognized, the ultimate goal of policy makers and advocates should be to ensure that all schools have comprehensive physical education programs (see Chapter 5).

Another program, Texas I-CAN!, helped teachers incorporate physical activity by modifying lesson plans to include more active activities, thereby increasing vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity by 1,000 steps per day (Bartholomew and Jowers, 2011). It was found that these curriculum-based activities improved time on task immediately following the breaks, especially in children who were overweight; these students went from being on task 58 percent of the time on typical instruction days to 93 percent of the time after the breaks (Grieco et al., 2009).

These findings emphasize the effectiveness and feasibility of providing classroom-based structured opportunities for physical activity. Breaks in the classroom provide an additional opportunity for physical activity throughout the school day with minimal planning, no equipment, and a short amount of time required; they can also incorporate learning opportunities for students. It should be noted that the literature tends to focus on the effect of classroom physical activity breaks on elementary school rather than secondary school students.

For classroom-based physical activity breaks to become a priority, it will be important to provide evidence that such breaks do not detract from academic achievement. Chapter 4 provides an extensive review of the evidence showing that physical activity in general has positive effects on academic performance. With respect to classroom-based physical activity, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010) reviewed studies examining the association between such activity and academic performance in elementary school–age children. Eight of nine published studies found positive effects on such outcomes as academic achievement and classroom behavior; only one study found no relationship (Ahamed et al., 2007), but that study also found that the breaks did increase physical activity levels and did not adversely affect academic achievement. Donnelly and Lambourne (2011) provide further support for the link between physical activity and positive cognitive and academic outcomes in elementary school–age children. In addition, studies in elementary school–age children have found an increase in on-task behavior in the classroom after participation in a physical activity break (Jarrett et al., 1998; Mahar et al., 2006; Mahar, 2011; see also Chapter 4). For example, Mahar and colleagues (2006) found that time on task increased by 8 percent (p < .017) with the implementation of a 10-minute break. They also found that the 20 percent of students who were off task improved the most in time on task. Similar

results were found in Georgia, where 4th graders exhibited significantly less fidgeting behaviors and significantly better on-task behaviors on days when activity breaks were conducted (Jarrett et al., 1998). Finally, a meta-analysis by Erwin and colleagues (2012) found that breaks increase the frequency of physical activity behaviors and have positive learning outcomes. It should be noted that the effect and benefits of classroom-based physical activity breaks in preschool populations have not been thoroughly investigated.

Policies That Affect Classroom Physical Activity Breaks

Classroom physical activity breaks are a relatively new approach to promoting physical activity during the school day. Consequently, research on policies that support or hinder the use of this approach is sparse. For this approach to become more prevalent, supportive policies will be necessary, an observation supported by the fact that just one in four U.S. public elementary schools offered children and youth physical activity breaks apart from physical education and recess during the 2009-2011 school years (Turner and Chaloupka, 2012). Research clearly demonstrates the important role of state laws and school district policies in promoting physical activity opportunities in schools. For example, schools are more likely to meet physical education recommendations when state laws and school district policies mandate a specific amount of time for physical education classes (Slater et al., 2012; see also Chapter 5). Currently, few if any school districts require that physical activity opportunities be provided throughout the school day or within the classroom (Chriqui et al., 2010). Therefore, research is needed to identify strategies for implementing classroom-based physical activity breaks and providing teachers with the skills and confidence necessary to engage students in these activities. In addition, questions remain about the optimal duration, timing, and programming (e.g., types of activities) for physical activity breaks (Turner and Chaloupka, 2012).

Barriers to Classroom Physical Activity Breaks

One factor that influences classroom physical activity breaks is competition for time during the school day, arising from the need for schools to meet the academic requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act (see Chapter 5). As discussed above and in Chapter 4, however, the literature clearly supports that classroom physical activity breaks are not only beneficial in promoting physical activity in children and youth but also can occur in the classroom without compromising learning and in fact improve academic performance and related classroom behaviors. In addition, research has shown that using innovative curriculum change, such as Physical Activity Across the Curriculum (Donnelly et al., 2009), can increase daily

physical activity and improve academic performance. Additionally, schools often have a scarcity of resources related to staffing, teacher training, funding, champions, and/or facilities for physical activity. Dwyer and colleagues (2003), for example, document the lack of facilities and equipment for physical activity breaks. As a result of these barriers, it has been found that, although teachers see the importance of physical activity breaks for children’s health and development, they infrequently integrate movement into the classroom (Parks et al., 2007).

From the literature, classroom physical activity breaks appear to be heavily implemented in early childhood and elementary classrooms (CDC, 2010). Few if any classroom physical activity breaks appear to occur in middle and high school settings. The lack of physical activity breaks for this age group may be due to the increased academic demands of testing, along with difficulty of implementing breaks that target these older students. However, classroom-based physical activity curricula are emerging at a rapid rate. Programs available for purchase include Active and Healthy Schools activity break cards, Promoting Physical Activity and Health in the Classroom activity cards, Energizers, and TAKE 10! Other resources for classroom physical activity breaks are available at no cost to schools, such as Jammin’ Minute, ABS for Fitness, Activity Bursts in the Classroom, Game On! The Ultimate Wellness Challenge, and approximately 50 others. These resources can be found through the Alliance for a Healthier Generation at www.healthiergeneration.org. They provide an excellent starting point for teachers and are flexible enough to be modified to meet the needs of specific classrooms.

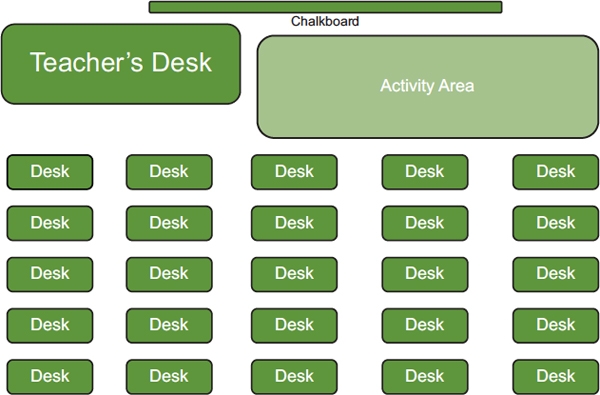

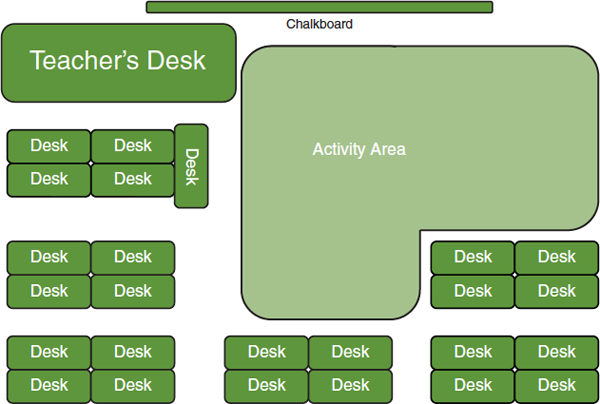

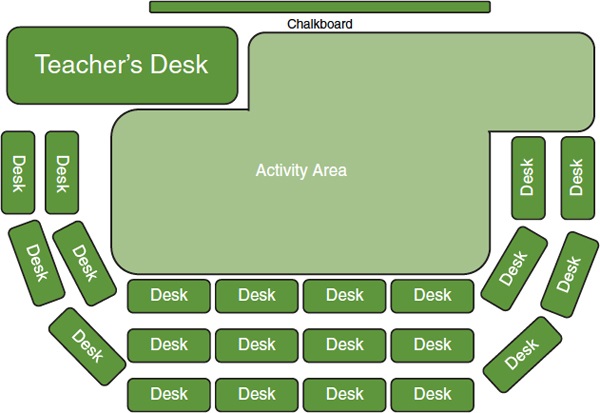

Space is another concern for classroom teachers, who must consider the safety of students. The classroom (e.g., desks and tables) needs to be arranged to provide adequate open space for students to move during physical activity breaks. Figure 6-1 shows the activity area/space available in a traditionally organized classroom. Figures 6-2 and 6-3 show how the classroom can be arranged to optimize the space for movement and physical activity.

Recess

One of the most common forms of physical activity break during the school day is recess. Children can accumulate up to 40 percent of their daily physical activity time during recess (Ridgers et al., 2006). Recess, according to Pellegrini and colleagues (1995), is the time of day set aside for students to take a break from their class work; engage in play with their peers; and take part in independent, unstructured activities. Recess is most common in elementary schools and is rare during the secondary years.

While separate and distinct from physical education, recess is an essential component of the total educational experience for elementary-age chil-

FIGURE 6-1 Traditional layout of a classroom with limited space for physical activity breaks.

SOURCE: Personal communication from Heather Erwin. Reprinted with permission from Heather Erwin.

FIGURE 6-2 One classroom layout designed to accommodate physical activity breaks.

SOURCE: Personal communication from Hearther Erwin. Rseprinted with permission from Heather Erwin.

FIGURE 6-3 Another classroom layout designed to accommodate physical activity breaks.

SOURCE: Personal communication from Heather Erwin. Reprinted with permission from Heather Erwin.

dren (Ramstetter et al., 2010). In addition to providing children the opportunity to engage in physical activity, develop healthy bodies, and develop an enjoyment of movement, it provides them with a forum in which they are able to practice life skills, including conflict resolution, problem solving, communicating with language, cooperation, respect for rules, taking turns, and sharing. Moreover, it serves as a developmentally appropriate outlet for reducing stress in children (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1998). Furthermore, recess facilitates attention and focus on learning in the classroom (NASPE, 2001). This dedicated period of time further allows children the opportunity to make choices, plan, and expand their creativity (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1998). Indeed, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recently released a policy statement in support of recess and free play as “fundamental component[s] of a child’s normal growth and development” (Council on School Health, 2013, p. 188).

The AAP further asserts that cognitive processing and academic performance depend on regular breaks from concentrated class work. The AAP believes that

• Recess is a complement to but not a replacement for physical education. Physical education is an academic discipline.

• Recess can serve as a counterbalance to sedentary time and contribute to the recommended 60 minutes or more of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per day.

• Peer interactions during recess are a unique complement to the classroom. The lifelong skills acquired for communication, negotiation, cooperation, sharing, problem solving, and coping are not only foundations for healthy development but also fundamental measures of the school experience.

The Decline of Recess

Since passage of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001, several studies and reports across the literature have pointed to a decline in recess to make more time for academic subjects. Approximately 40 percent of schools in the United States have either eliminated or reduced recess in order to free up more time for academics (RWJF, 2010). See Table 6-1 for a summary of changes in recess time between 2001 and 2007; see also the detailed discussion of time shifting in Chapter 5.

The Recess Gap

In addition to the general decline in recess time, the Center for Public Education (2008) has identified a “recess gap” across school settings. This finding is supported by the results of a survey sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education and the National Center for Education Statistics (Parsad and Lewis, 2006), which collected information from a representative sample of 1,198 U.S. elementary schools on whether they scheduled any recess for each grade, typically grades 1 through 5 or 6. Respondents reported the number of days per week of scheduled recess, the number of times per day, and the total minutes per day for each elementary grade in

TABLE 6-1 Change in Recess Time, 2001-2007

| Districts with At Least One School Identified as “In Need of Improvement” | Districts with No Schools Identified as “In Need of Improvement” | Total | |

| Percent decreasing recess time | 22 | 19 | 20 |

| Average decrease in recess (minutes per week) | 60 | 47 | 50 |

SOURCE: Center on Education Policy, 2007.

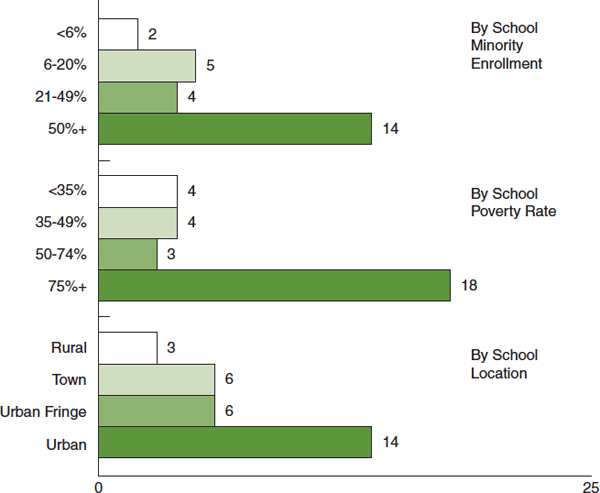

FIGURE 6-4 Percent of schools that do not provide recess to 1st graders.

NOTE: Poverty rate is based on the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunches.

SOURCE: Parsad and Lewis, 2006. Reprinted with permission.

2005. The survey found that while most children, regardless of location, continue to get recess on a regular basis, children who attend high-minority, high-poverty, or urban schools are far more likely than other children to get no recess at all (see Figure 6-4). Also:

- The proportion of public elementary schools with any scheduled recess ranged from 87 to 93 percent across elementary grades.

- The proportion of public elementary schools with no scheduled recess ranged from 7 to 13 percent across elementary grades.

- Fourteen percent of elementary schools with a minority enrollment of at least 50 percent scheduled no recess for 1st graders, compared with 4 percent of schools with 21-49 percent minority enrollment, 5 percent of those with 6-20 percent minority enrollment, and 2 percent of those with less than 6 percent minority enrollment.

- Eighteen percent of elementary schools with a poverty rate over 75 percent (based on the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunches) provided 1st graders with no recess, compared with 3 percent of schools with a 50-74 percent poverty rate, 4 percent with a 35-49 percent poverty rate, and 4 percent with a less than 35 percent poverty rate.

- Fourteen percent of urban elementary schools did not offer recess to 1st graders, compared with 6 percent of schools on the urban fringe, 6 percent of those in towns, and 3 percent of rural schools.

The above patterns for 1st graders persisted through 6th grade: 24 percent of 6th graders in high-minority schools, 28 percent in high-poverty schools, and 24 percent in urban schools did not get recess, compared with 13 percent of 6th graders overall.

The National Association of State Boards of Education’s (NASBE’s) Center for Safe and Healthy Schools (2013) State School Healthy Policy Database supports the above survey findings. It shows that most public elementary schools (83-88 percent) offer daily recess across elementary grades, while 47 percent offer it 1-4 days per week:

- Large schools generally are less likely than small- and medium-sized schools to have daily recess for 1st through 3rd grades.

- City schools are less likely than schools in other locales to offer daily recess for 1st graders. City schools also are less likely than schools in urban fringes and rural areas to schedule daily recess for 2nd through 5th grades.

- Schools with the highest poverty concentrations are less likely than those with lower poverty concentrations to offer daily recess for elementary grades.

- Differences also exist by minority enrollment, with schools with the highest minority enrollment being less likely than those with lower minority enrollment to provide daily recess.

The percentage of public elementary schools offering more than 30 minutes per day of recess ranges from 19 to 27 percent across elementary grades. The average number of minutes per day of scheduled recess for elementary grades differs by school characteristics. Large schools on average offer fewer average minutes per day of recess than small- and medium-sized schools; the same is true for schools with the highest and lowest poverty concentrations, respectively. For further detail, a state-by-state list of policies from the NASBE State School Health Policy Database can be found in Appendix C.

Since physical activity, such as recess, has been shown to improve academic achievement, this recess gap may contribute to, not decrease, disparities in academic achievement.

Support for Recess

Both international and U.S. organizations support the importance of recess.

International organizations Aside from the historical literature on the need for children to play (dating back to the 1600s), the most prominent and widespread support for recess is rooted in the International Play Association and its work through the United Nations (UN). The International Play Association, founded in 1961 in Denmark, is a global nongovernmental organization that protects, preserves, and promotes children’s fundamental human right to play. The UN’s Declaration of the Rights of the Child (1959), Article 7, Paragraph 3, states:

The child shall have full opportunity for play and recreation which should be directed to the same purposes as education; society and the public authorities shall endeavor to promote the enjoyment of this right.

The declaration asserts that spontaneous play fulfills a basic childhood developmental need. It further defines play as “a combination of thought and action that is instinctive and historical and that teaches children how to live” (IPA, 2013). At the 1989 UN General Assembly, the International Play Association played a key role in the inclusion of “play” in Article 31 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. It reads:

That every child has the right to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts. That member governments shall respect and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall encourage the provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and leisure activity. (IPA, 2013)

The U.S. affiliate of the International Play Association has as its primary goal to protect, preserve, and promote play as a fundamental right for all children.

U.S. organizations In a 2013 policy statement, the AAP asserts that recess is a crucial and necessary component of a child’s development and as such should not be withheld for punitive or academic reasons. The AAP stresses that minimizing or eliminating recess may be counterproductive to academic

achievement, as mounting evidence suggests that recess promotes physical health, social development, and cognitive performance (AAP, 2013).

Through three sponsored research studies, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) further supports the need for recess in schools. Recess Rules: Why the Undervalued Playtime May Be America’s Best Investment for Healthy Kids in Healthy Schools (RWJF, 2007) states that recess represents an unparalleled chance to increase physical activity among a large number of children in the United States, as well as an underutilized opportunity to improve the overall learning environment in the nation’s schools. For a second study conducted by RWJF (2010), The State of Play, 1,951 elementary school principals participated in a Gallup survey devoted to the subject of recess. The survey sample was provided by the National Association of Elementary School Principals, and it reflects a balance of urban, suburban, and rural schools and schools of different income levels, as defined by the percentage of students receiving free or reduced-price lunches. The results show that principals overwhelmingly believe that recess has a positive impact not only on the development of students’ social skills but also on achievement and learning in the classroom. When asked what would improve recess at their schools, they highlighted an increase in the number of staff to monitor recess, better equipment, and playground management training, in that order.

According to a third RWJF and Active Living Research study, School Policies on Physical Education and Physical Activity (Ward, 2011):

- “Whole-school programs that provide opportunities for physical activity across the school day—through recess, in-class breaks, and after-school events—increase children’s physical activity levels.”

- “Schools that provide ample time for supervised recess and access to equipment, as well as those that make low-cost modifications to improve play spaces, have more physically active students.”

- “Activity breaks during classes not only increase physical activity but also help children focus better on academic tasks and enhance academic achievement.”

Other national organizations and studies further support the need for recess in elementary schools:

- The National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education takes the position that “recess is an essential component of education and that preschool and elementary school children must have the opportunity to participate in regular periods of active play with peers” (National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education, 2001, p. 1).

- The National Association for the Education of Young Children (2001) believes that unstructured play is a developmentally appropriate outlet for reducing stress in children, improves children’s attentiveness, and decreases restlessness.

- Through a position statement, Recess in Elementary Schools, the National Association for Sport and Physical Education, Council on Physical Education for Children, asserts:

Recess also provides the opportunity for students to develop and improve social skills. During recess, students learn to resolve conflicts, solve problems, negotiate, and work with others without adult intervention. Cognitive abilities may also be enhanced by recess. Studies have found that students who do not participate in recess may have difficulty concentrating on specific tasks in the classroom, are restless and may be easily distracted. In addition, recess serves as a developmentally appropriate strategy for reducing stress. Contemporary society introduces significant pressure and stress for many students because of academic demands, family issues, and peer pressures. (NASPE, 2001)

- The National Parent Teacher Association (PTA) and the Cartoon Network launched “Rescuing Recess” in 2006 to help sustain and revitalize the importance of recess in schools across the country. The goal of the campaign is to recognize unstructured break time as an essential element of the school day and to connect educators, parents, and children as advocates for bringing back or retaining recess. A 2006 nationwide survey of PTA leaders found that parents and teachers also think taking a break is a vital part of a child’s school day (National Parent Teacher Association, 2006).

Barriers to Recess

The evidence supporting the cognitive, health, and social benefits of recess could become a thesis on its own merits. Despite these benefits, however, few states have specific policies requiring recess, and those that do have such policies often defer to local school districts to allow individual schools to determine whether students will have a recess period.

Policies requiring increased activity at school each day have the potential to affect large numbers of children and are an effective strategy for promoting regular physical activity. However, external and internal barriers to policy implementation need to be considered (Amis et al., 2012). Competing time demands, shorter school days, lack of teacher participation, and lack of adequate facilities have all been cited as barriers to providing recess (Evenson et al., 2009). Further, weak policies suggesting or recommending changes have shown little or no effect on changing behavior

(Ward, 2011; Slater et al., 2012). Additional barriers to enacting effective policies include a lack of earmarked resources devoted to policy implementation, principals’ lack of knowledge of the policy, and no accountability mechanisms to ensure policy implementation (Belansky et al., 2009).

In addition, the National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education (2002) identifies issues of student safety, lack of adult supervision, potential lawsuits for injured students, and potential for children to come into contact with strangers entering school grounds as barriers to recess. Elementary school principals responding to the above-referenced RWJF (2010) Gallup survey also cited liability and safety issues, as well as access to space and weather.

Strategies for Reviving Recess

Several strategies can be used to promote recess in schools, along with engagement in physical activity among youth participating in these programs. First, it is necessary to provide a safe environment with ample recreational equipment to encourage physical activity. Additionally, regulations should be in place to ensure that schools offer at least 20 minutes of recess per day. It is imperative as well that training be provided to recess supervisors and staff, with a focus on both safety issues and ways to interact with students to better promote physical activity. Recess is not a common occurrence for secondary students; however, they could participate in a civic- or service-oriented program whereby they would oversee and engage in recess for local elementary schools.

Intra- and Extramural Sports

Sports programs have long been an integral part of the school setting. Sport is one of the four human activities, along with play, games, and work. According to Woods (2011, pp. 5-6), play is a “free activity that involves exploration, self-expression, dreaming, and pretending. Play has no firm rules and can take place anywhere.” Children’s play often involves physical movement. Games are forms of play “that have greater structure and are competitive. Games have clear participation goals … [and] are governed by informal or formal rules” (p. 5). Games can be sedentary or physical; involve competition, planning, and strategizing; and result in “prestige or status.” Sport is a specialized or higher order of play or games with special characteristics. It must involve physical movement and skill. It must be “competitive with outcomes that are important to those involved,” and “winning and losing are a critical part of competition.” Thus, an important aspect of sport is institutionalized competition under formal rules. Lastly, work is “purposeful activity that may include physical and mental effort

to perform a task, overcome an obstacle, or achieve a desired outcome.” Sport can be work.

It is important to note that children in schools can participate in sports as either players or spectators. Kretchmar (2005) suggests that playing sports at a young age tracks to becoming a loyal spectator in later years; however, being a spectator at a young age may not necessarily lead to active participation as a player. Chen and Zhu (2005) analyzed intuitive interest in physical activity among 5-year-olds using the nationally representative sample from the U.S. Department of Education’s Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. The results of a logistic regression analysis showed that early exposure to watching a sport may have a negative effect on developing interest in actually playing the sport.

The discussion here focuses on institutionalized in-school sports and on children’s participation as players. In-school sports programs typically fall into two categories: intramural, or within a school, and extramural or interscholastic, or competition between schools (AAHPERD, 2011). The type and scope of each of these categories of sports vary by school size (Landis et al., 2007), location, and the socioeconomic status of students (Edwards et al., 2013).

In the past 40 years, participation in sports has flourished both within and outside of schools. Although young children are not eligible for formal interscholastic competition until they reach secondary school, children (or their parents) with athletic aspirations start preparation for competition at a very young age. Results of the National Survey of Children’s Health (2007) showed that approximately 58.3 percent of 6- to 17-year-olds participated in sports teams or lessons over a 12-month period. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2012) reports that in 2011, 58 percent of high school students played on at least one sports team. Intramural sports clubs in middle and high schools also involve large numbers of students.

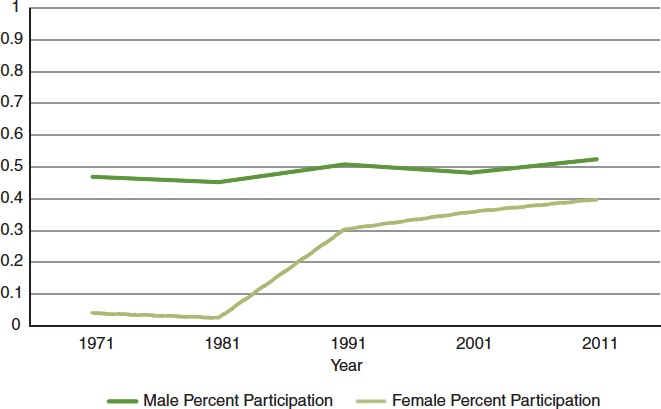

Participation in sports inside and outside school has increased in the past 20 years. According to the latest report of the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFSHSA) (2012), participation in high school sports nearly doubled in 2011-2012 relative to 1971-1972. While boys’ participation increased by about 22 percent during these years, girls’ participation increased about 10-fold. Table 6-2 documents the change by decade.

Figure 6-5 shows the ratio of growth in boys’ and girls’ participation in sports relative to the total enrollment in U.S. high schools during the five decades. The data show that while the ratio for boys has remained steady at about 40-50 percent, the ratio for girls has increased from 4 percent in 1971-1972 to 40 percent in 2011-2012.

Nationwide, 77 percent of middle schools and 91 percent of high schools offer at least one interscholastic sport (Lee et al., 2007), and 48 per-

TABLE 6-2 Change in Participation in High School Sports in the Past Five Decades

| School Year | Boys | Girls | ||

| Participants | Enrollment | Participants | Enrollment | |

| 1971-1972 | 3,667,000 | 7,819,000 | 294,000 | 7,364,000 |

| 1981-1982 | 3,409,000 | 7,541,000 | 1,811,000 | 7,101,000 |

| 1991-1992 | 3,430,000 | 6,754,000 | 1,941,000 | 6,392,000 |

| 2001-2002 | 3,961,000 | 8,224,000 | 2,807,000 | 7,836,000 |

| 2011-2012 | 4,485,000 | 8,553,000 | 3,208,000 | 8,060,000 |

NOTE: Rounded to the nearest 1,000. Participants total is the sum of participants in school sports; if a student participated in more than one sport, he or she would be counted for each of those sports.

SOURCE: Adapted from NFSHSA, 2012.

FIGURE 6-5 Change in the ratio of males’ and females’ participation in sports relative to enrollment, 1971-2011.

NOTE: Ratio is number of participants divided by estimated number of males or females enrolled in high school in October of the enrollment year. Enrollment data were adapted from the U.S. Census Bureau’s October Current Population Survey. For 1971 and 1981, only the total number of students was available, and the proportion of male students was assumed to be 0.515.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, 1971-2011.

cent of middle and high schools offer intramural sports or physical activity clubs (NASPE and AHA, 2010). Based on data from a nationally representative sample of middle schools, Young and colleagues (2007) found that 83 percent of schools offered interscholastic sports, and 69 percent offered intramural sports and clubs. No reports indicate that interscholastic or intramural sports were offered in elementary schools.

Many students who do not play on school teams may participate in sports programs outside of school. CDC (2012) data indicate that 58 percent of high school–age youth played on at least one sports team in 2011, which suggests that an estimated 31 million of the 55 million youth in this age group participated in sports outside of school. The committee was unable to find a national estimate of the number of students who participated in school intramural sports or physical activity clubs. However, one study of four middle schools with similar demographic populations based on race/ethnicity, income, and geographic location suggests that the intramural sports environment may be more conducive to increased physical activity levels than the environment of varsity sports, at least for middle school boys (Bocarro et al., 2012). This may be due in part to the fact that all children can participate in intramural activities without having the high skill levels required for interscholastic sports.

Students have many choices of interscholastic sports. Lee and colleagues (2007) cite 23 popular sports, grouped in Table 6-3 as team or individual sports. Lee and colleagues (2007) believe that most individual sports may be more likely than team sports to become lifelong activities for individual students.

Policies That Affect Participation in Sports

As with physical education and recess policies, data from both the Shape of the Nation Report (NASPE and AHA, 2010) and the NASBE State School Health Policy Database (see Appendix C) show variations in amounts, accountability, and regulations for high school sports. Twenty-one states (41 percent) had state requirements regarding sports, most relating to gender equity, concussion management, and local requirements. Although NFSHSA remains the governing body for individual state athletic associations, the governance of district sports opportunities is determined largely by local athletic associations in accordance with individual state association requirements. However, decisions on what sports to offer, the frequency of sport competitions, and other factors are made at the local level. In its report on the Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program (CSPAP), the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (AAHPERD) (2011) notes that 65 percent of high

TABLE 6-3 Interscholastic Sports Choices and Percentage of Middle and High Schools Offering Them

| Sport | Middle Schools (percent) | High Schools (percent) | |

| Team Sports | |||

| Baseball | 35.7 | 79.6 | |

| Basketball | 76.4 | 90.9 | |

| Cheerleading | 50.9 | 77.3 | |

| Field hockey | 7.1 | 10.2 | |

| Football | 53.0 | 71.0 | |

| Ice hockey | 2.4 | 14.3 | |

| Lacrosse | 2.1 | 3.8 | |

| Soccer | 32.3 | 60.3 | |

| Softball | 45.2 | 77.9 | |

| Volleyball | 57.3 | 71.4 | |

| Water polo | 0.5 | 2.6 | |

| Individual Sports | |||

| Badminton | 4.2 | 7.2 | |

| Bowling | 3.0 | 17.2 | |

| Cross-country running | 38.9 | 68.4 | |

| Cross-country skiing | 3.2 | 5.9 | |

| Golf | 22.1 | 68.4 | |

| Gymnastics | 5.2 | 10.1 | |

| Riflery | 2.1 | 3.8 | |

| Swimming | 6.9 | 37.8 | |

| Tennis | 12.6 | 53.0 | |

| Track and field | 52.1 | 73.2 | |

| Weight lifting | 9.9 | 23.8 | |

| Wrestling | 28.7 | 49.6 | |

| SOURCE: Adapted from Lee et al., 2007. | |||

schools implemented various forms of team-cut policies for participation in interscholastic sports. The practice requires students to meet minimum performance qualifications before joining a school-sponsored sports team. Such policies include maintaining a designated grade point average, meeting daily attendance requirements, and adhering to individual school district code-of-conduct policies. One might speculate that such policies may prohibit interscholastic sports from becoming a viable means of promoting maximum student participation in sports and other physical activity.

In summary, trends in participation in sports are encouraging. Compared with physical education, however, it is difficult to expect every child to participate in sports. Although the available data indicate a nearly 60 percent participation rate, the data do not provide specific information

about the participants. In addition, studies and national surveys have not provided useful information about those children who do not participate in sports, who may be in the greatest need of physical activity. Although the opportunity for physical activity through participation in interscholastic and/or intramural sports does exist in most secondary schools, the extent to which participation in sports contributes to children’s health and positive behavior change for active living is unclear.

Barriers to Participation in Sports

Although the literature documents the benefits of participating in high school sports in such areas as academic achievement, attendance, and self-esteem, opportunities for participation in sports have not escaped the effects of the budget cuts that have plagued education over the past several years (Colabianchi et al., 2012).

In addition, interscholastic sports have been dominated by a competitive sports model (Lee et al., 2007), which may fail to engage and support all students. Policies encouraging and funding intramural sports, which are usually more inclusive and less competitive, can increase student participation in sports. The CDC recommends inclusive policies and programs as a strategy for enabling students to meet the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines (HHS, 2008).

According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO) (2012) report K-12 Physical Education: School-Based Physical Education and Sports Programs, school district officials assert that budget cuts have impacted predominantly transportation and facilities, both critical to after-school sports programs (GAO, 2012). According to data from the School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS) (2006) (Lee et al., 2007), an estimated 29 percent of schools that offered interscholastic sports in 2006 also provided transportation home for participating students, up from 21 percent in 2000. Transportation costs, a large part of overall school athletic budgets, are impacted not only by the need to transport students to practice facilities and competition venues and then home but also by increases in fuel prices and maintenance costs.

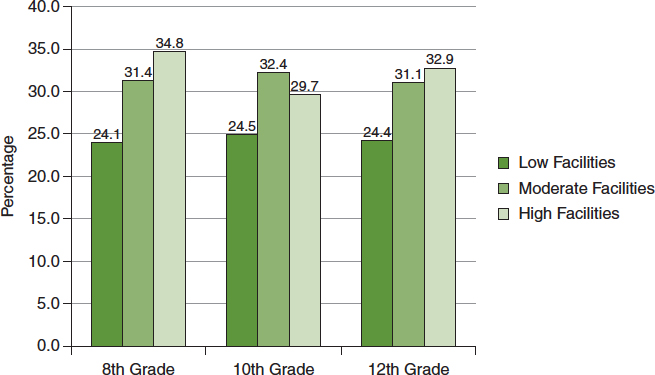

Facilities and equipment are another recognized barrier to participation. Budget cuts have hindered school districts from building new facilities or upgrading existing ones. Where facility and land limitations prevail, school districts have resorted to developing partnerships and contractual agreements with local community recreation centers or universities to use their facilities for various sports program. A lack of funding for sports equipment has further reduced the number of participating students, as the number of uniforms available per sport has caused the selection process to become more stringent. Colabianchi and colleagues (2012) also conclude

that the percentage of students participating in interscholastic sports is contingent on the type and number of facilities (see Figure 6-6).

Another challenge to implementing quality sports programs is the availability of quality coaches. Fewer school personnel are coaching in the face of a decline in coaching supplements and increased time commitments. Funding for staffing or staff training is an important aspect of successful sports or after-school physical activity programs. According to the 2006 SHPPS data, more than half of schools surveyed paid staff for involvement in intramural sports programs (Lee et al., 2007). Policies to support supervisory staff can facilitate increased opportunities for physical activity for students.

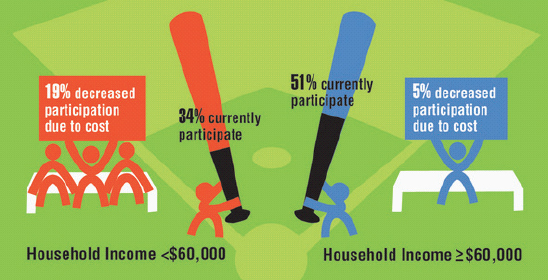

Constrained budgets also have reduced the number of sports offerings, with the primary sports being retained and the second-tier sports, such as golf and tennis, either being eliminated or requiring that students pay 100 percent of the cost of participation. Indeed, many school districts across the United States have implemented a pay-to-play policy. According to the 2006 SHPPS data, 33 percent of schools require students to pay to participate in interscholastic sports. A study released by the University of Michigan, C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital (2012), reports that pay-to-play fees are preventing lower-income children from participating in both middle and high school sports. The study found that the average fee was $93 per sport, while some respondents to the survey reported paying $150 or more.

FIGURE 6-6 Participation in interscholastic sports among boys and girls by availability of sports facilities, 2009-2011.

SOURCE: Colabianchi et al., 2012. Figure 6-6.eps

When combined with the cost of equipment, uniforms, and additional team fees, the average total cost for a child’s participation in sports was $381. Nineteen percent of families making under $60,000 reported that costs had led to at least one of their children being unable to participate in sports. Figure 6-7 shows the study results regarding participation in school sports among youth aged 12-17 by household income. The study found further that

- More than 60 percent of children who played school sports were subject to a pay-to-play fee; only 6 percent received waivers for the fee.

- Only one-third of lower-income parents reported that their child participated in school sports, compared with more than half of higher-income parents.

- In lower-income households, nearly one in five parents reported a decrease in their child’s participation in school sports because of cost.

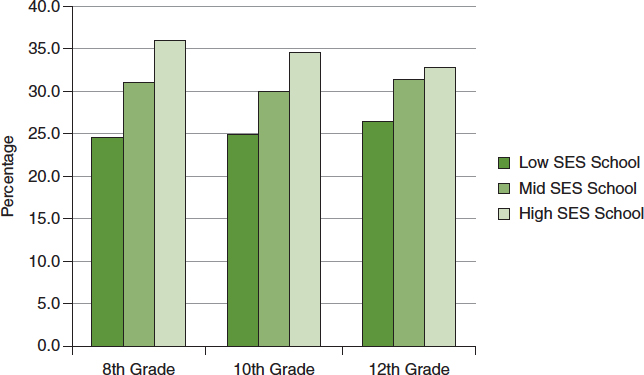

Colabianchi and colleagues (2012) further determined that the percentage of students participating in sports varied with the students’ socioeconomic status. Participation was higher at schools of mid-socioeconomic status than at those of low socioeconomic status, and even higher at schools of high socioeconomic status compared with those of mid-socioeconomic status (see Figure 6-8).

Interscholastic sports have been criticized for perpetuating racial and gender segregation (Lee et al., 2007). Further study by Kelly and colleagues (2010) and Bocarro and colleagues (2012) confirmed the relationship

FIGURE 6-7 Participation in school sports for youth aged 12-17 by household income.

SOURCE: C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, 2012.

FIGURE 6-8 Participation in interscholastic sports by school socioeconomic status among boys and girls, 2009-2011.

NOTE: SES = socioeconomic status.

SOURCE: Colabianchi et al., 2012.

between socioeconomic status and sports participation, finding that fewer children and adolescents in schools of low socioeconomic status or with a relatively high proportion of racial and ethnic minority groups participated in sports programs.

To provide the physical activity and psychosocial benefits of engaging in sports at school, education systems need to reevaluate their budgets to ensure that equitable sports opportunities are available for youth in all types of school settings and at all levels of socioeconomic status. The same holds true with respect to ensuring that school-based intramural sports opportunities are available before or after school hours to increase participation in physical activity among all students.

Programs for Students with Disabilities

The 2010 GAO report Students with Disabilities: More Information and Guidance Could Improve Opportunities in Physical Education and Athletics notes that students with and without disabilities were provided similar opportunities to participate in physical education in schools but identifies several challenges to serving students with disabilities. Likewise, for sports, opportunities were provided for students to participate, but students with disabilities participated at lower rates than those without disabilities. Yet sports programs for students without disabilities have shown

similar benefits for students with disabilities, including not only obesity reduction but also higher self-esteem, better body image, and greater academic success; more confidence and a greater likelihood of graduating from high school and matriculating in college; and greater career success and more career options (GAO, 2010; Active Policy Solutions, 2013; U.S. Department of Education, 2013).

To ensure that students with disabilities have opportunities to participate in extracurricular athletics equal to those of other students, the GAO report recommends that the U.S. Department of Education clarify and communicate schools’ responsibilities under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 regarding the provision of extracurricular athletics. Most important, the report recommends improving physical education and athletic opportunities for students with disabilities and recommends that (1) the Secretary of Education facilitate information sharing among agencies, including schools, on ways to provide opportunities, and (2) clarify schools’ responsibilities under federal law, namely Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, through the Office for Civil Rights, which is responsible for enforcing Section 504. In January 2013, in a landmark response to the release of the 2010 GAO report, the U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights (2013), clarified a school’s role in providing extracurricular athletic opportunities for students with disabilities.

Active Transport

Active transport or active commuting refers to the use of walking, biking, or other human-powered methods (e.g., skateboarding). It includes using public transportation or “walking school buses,” or being driven to a point closer to but not at school from which students walk the remainder of the way. Active transport equates to moderate-intensity physical activity, which, as discussed in earlier chapters, provides crucial health benefits. In light of these benefits, the CDC has launched programs to encourage parents to walk their children to school.

Active commuting has been proposed as an ideal low-cost strategy to increase physical activity within the general population and can account for one-quarter of an individual’s recommended total daily steps (Whitt et al., 2004). Studies have found that active transport provides children with physical activity (Tudor-Locke et al., 2002) and increased energy expenditure (Tudor-Locke et al., 2003). Bassett and colleagues (2013) suggest that active transport to and from school contributes on average 16 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity for youth. These benefits, together with concern about increased traffic congestion and air pollution, have led to growing interest in the use of active transport by youth to get to and from school (Kahlmeier et al., 2010). In addition, it has been suggested

that active transport enhances social interaction among children and promotes independent mobility (Collins and Kearns, 2001; Kearns et al., 2003).

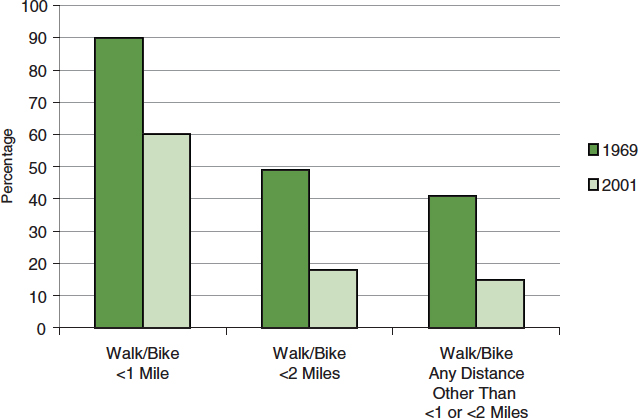

Five decades ago, children actively commuting to school were a common sight. Nearly 90 percent of children who lived within a 1-mile radius of school either walked or biked to school (USDOT, 1972). Since 1969 the prevalence of youth walking or biking to school has steadily declined (McDonald, 2007), paralleling a decline in active commuting among American adults (Pucher et al., 2011). Data from the U.S. Department of Transportation show the decline in active transportation to and from school between 1969 and 2001 (see Figure 6-9).

From an international perspective, active transport among children and adolescents is more prevalent in European countries such as the Netherlands and Germany, which have a culture of active transport, than in other regions. These countries tend to have a lower risk of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension in youth compared with the United States. Indeed, the data support an inverse relationship between the percentage of active transport and obesity rates among residents of the United States, Canada, Australia, and 14 European countries (Bassett et al., 2008). In this study

FIGURE 6-9 Decline in active transportation to and from school among youth from 1969 to 2001 in the United States.

SOURCE: CDC, 2008; 1969 Nationwide Personal Transportation Survey (USDOT, 1972); and 2001 National Household Travel Survey.

the United States ranked the lowest on active transport and the highest on obesity prevalence.

Policies That Affect Active Transport

Various environmental and policy factors support or hinder active transport to and from school. For example, school siting policies that encourage the construction of schools on large campuses far from residential areas and not integrated with housing development are a hindrance (Council of Educational Facility Planners International, 1991). Accordingly, efforts are being made to stop “school sprawl,” including eliminating minimum acreage guidelines so that schools can be located closer to where school-age children live (Salvesen and Hervey, 2003).

At the national level, the U.S. Secretary of Transportation has called for a “sea change” in transportation planning in the United States. He has expressed the need to put cyclists and walkers on even ground with motorists and issued a policy statement on accommodations for active transport (USDOT, 2010). His statement calls for the redesign of existing neighborhoods with bicycle lanes, sidewalks, and shared paths. Additionally, the reauthorization of federal transport legislation charged the Federal Highway Administration with providing funds for states to create and implement Safe Routes to School programs (National Safe Routes to School Task Force, 2008). Provision of this funding may increase the percentage of children who walk or bike to school through a variety of initiatives, including engineering (e.g., building sidewalks), enforcement (e.g., ticketing drivers who speed in school zones), education (e.g., teaching pedestrian skills in the classroom), and encouragement (e.g., having students participate in walk-to-school days) (CDC, 2005).

Eyler and colleagues (2008) examined policies related to active transport in schools. In 2005, six states (California, Colorado, Massachusetts, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Washington) had statewide safe routes to school or active transport programs. California, Colorado, and South Carolina had regulations regarding the required distance students must live from a school to be eligible for bus transportation (more than 1.5 miles in South Carolina). A review of the NASBE (2012) State School Health Policy Database revealed that only 11 states (21 percent) had legislation requiring walk/bike programs, most in partnership with the state departments of transportation (see Appendix C).

Barriers to Active Transport

Several factors contribute to the lack of active transport of youth to and from school. The first is accessibility (Frank et al., 2003), which refers to the proximity (i.e., within a 1-mile radius) of a child’s home to school

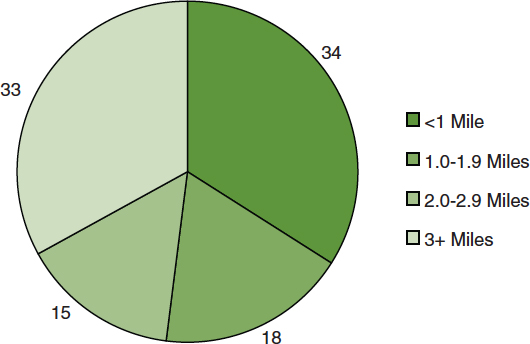

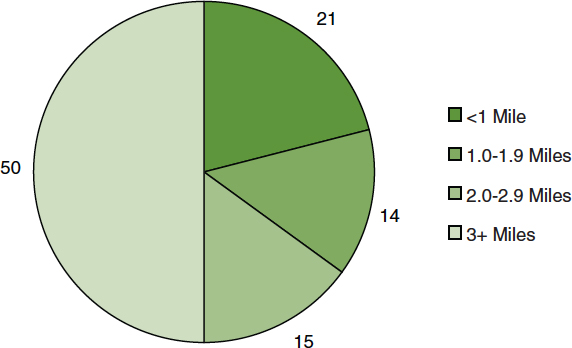

(Bassett, 2012). Nearly half of the decline in youth walking to and from school from 1969 to 2001 is attributable to the increased distance between home and school (McDonald, 2007). Proximity to school is influenced by families moving farther away from school; schools are being built farther away from homes compared with the small neighborhood schools of the past (see Figures 6-10 and 6-11). Proximity also is influenced by the decrease in the number of schools since 1960 even as the number of students enrolled in schools has increased (Wirt et al., 2003).

Proximity to school is not the only factor accounting for the decline in active transport among youth, as a significant decline also has been seen among youth living within a 1- to 2-mile radius of school. A second key determinant is infrastructure (Frank et al., 2003). The built environment is key to facilitating active transport. For active transport to be effective, not only must schools be in close proximity to the neighborhoods of students, but sidewalks, pedestrian crossings, and traffic lights must be adequate (Boarnet et al., 2005; Fulton et al., 2005). Boarnet and colleagues (2005) found that children’s walking and cycling to and from school greatly increased in urban areas with improvements in sidewalks, traffic lights, pedestrian crossings, and bike paths. In a national study of 4th to 12th graders, the presence of sidewalks was the main modifiable characteristic associated with active transport to and from school (Fulton et al., 2005). Other parental concerns include street connectivity, busy streets on

FIGURE 6-10 Distance to school for youth aged 5-18, 1969.

SOURCE: CDC, 2008.

FIGURE 6-11 Distance to school for youth aged 5-18, 2001.

SOURCE: CDC, 2008.

routes, and mixed land uses (Ewing and Greene, 2003; Fulton et al., 2005; Schlossberg et al., 2006; Timperio et al., 2006).

All nine schools interviewed for one study by active transport programs reported that the environmental factors that most affected these programs were sidewalks, crossing guards/crosswalks, funding, personal safety concerns, and advocacy group involvement. All schools also reported that a school speed zone was the greatest concern (Eyler et al., 2008). Other environmental factors include weather (heat, humidity, precipitation) and geographic location (Pucher and Buehler, 2011), with the South having a built environment less conducive to active transport compared with the Northeast, Midwest, and West (Bassett, 2012).

Related to infrastructure issues are parental concerns about safety (Loprinzi and Trost, 2010). These concerns include traffic dangers (Dellinger and Staunton, 2002). For example, 50 percent of children hit by cars near schools are hit by cars driven by parents of students (CDC, 2008), and drivers often exceed the posted speed limit and/or violate traffic signage in school zones (CDC, 2008). Safe routes to school initiatives that have linked engineers and educators to make school trips safer have seen a 64 percent increase in the percentage of students walking to school (Boarnet et al., 2005). In urban areas, infrastructure is conducive to active commuting to and from school, but these areas may be characterized by high crime rates. Dellinger and Staunton (2002) propose that safety is of particular concern for primary school children, which may account for their finding

that parents rated their child’s age as the most important factor in their decision to allow the child to walk to school. Other studies confirm that many 5- to 6-year-olds lack the skills to cope with traffic issues (Whitebread and Neilson, 2000), although other studies have found that neighborhood safety is unrelated to commuting practices in children (Humpel et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2004). The “walking school bus” (i.e., when an adult escorts a group of children to school) has been shown to be an effective means of safely transporting children to and from school (Collins and Kearns, 2005). It may be noted that pedestrian and bicycling injury/death rates among youth have declined by 51 percent and 60 percent, respectively. However, the decrease in walking or biking among youth may have contributed to this downward trend (CDC, 2008).

Finally, parents identify the perceived fitness level of their children as a determinant of the children’s participation in active transport. Specifically, parents who perceive their children as being unfit prefer passive transportation (Yeung, 2008).

“Walking School Bus” Programs

School-endorsed “walking school buses” may address several of the barriers identified above—in particular, traffic and crime dangers (White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity, 2010). “Walking school buses” are popular means for walking young children to school securely in Europe and Australia but are just starting to emerge in the United States. A “walking school buses” often entails one or two adult volunteers escorting a group of children from pickup points or their homes to school along a fixed route, starting with the pickup point or home that is farthest from the school and stopping at other pickup points or homes along the way. For increased security for the youngest children, a rope that surrounds the group can be used. On the way back from school, the same system is used in the opposite direction.

The White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity’s (2010) Report to the President identifies “walking school buses” as a low-cost initiative that communities can undertake to increase physical activity among elementary school children. The prevalence of “walking school buses” remains low in the United States but is growing; in 2008-2009, about 4.2 percent of a representative sample of public elementary schools organized “walking school buses”, with an increase to 6.2 percent in 2009-2010 (Turner et al., 2012). Examples of “walking school buse” programs are described in Box 6-2.

Parents’ engagement in school-based health promotion activities is another significant benefit of “walking school buses”. In some communities, “walking school buses” have provided opportunities for parents and

other volunteers to remain engaged in the life of the community while increasing their own physical activity.

Differences in Opportunities for Active Transport

The literature demonstrates that active transport varies among socioeconomic and ethnic groups and with the type of area (suburban, urban, or rural) (Davis and Jones, 1996; Dovey, 1999). Data from Bridging the Gap (Turner et al., 2010) demonstrate that one in four middle school students and one in eight high school students commute actively to and from school. Students of low socioeconomic status and those who attend schools where the majority of students are nonwhite (i.e., black and Latino) are more likely to walk or bike to and from school than those of high socioeconomic status and those who attend schools with a predominantly white student body.

Facilitators of Active Transport to School

Four common themes have been identified among schools with successful active transport to school programs (Eyler et al., 2008):

- collaboration among many organizations and individuals, including school personnel, public safety officials, city officials, parents, and school district representatives;

- funding for personnel, program materials, and improvements to the built environment;

- concerns about both traffic and crime being addressed; and

- efforts to make the built environment more conducive to active transport by students.

The same study identified a number of important and specific factors and policies to be considered (see Table 6-4).

A useful five-component framework for planning programs to enhance active transport to school has been suggested (Fesperman et al., 2008). This framework begins with the development of a plan and the enlistment of key individuals and organizations for input and support. The planning phase is crucial and may take a full year. The implementation of programmatic activities (e.g., training in pedestrian and bicycle safety, walk-to-school days), policy changes (e.g., school speed zones, modification of school start and dismissal times), and physical changes (e.g., sidewalk improvement, installment of traffic calming devices) follow in a sequence appropriate for the specific school and plan. For all activities, promotional materials to ensure understanding and continued support should be disseminated.

BOX 6-2

Examples of “Walking School Bus” Programs