Status and Trends of Physical Activity Behaviors and Related School Policies

Key Messages

• Few children in the United States, probably no more than half, meet the currently recommended standard of at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity daily.

o The proportion meeting the standard declines with age, with more elementary school children than middle and high school students achieving the goal. Boys are more likely than girls to meet the recommendation.

o During the past 30-40 years, probably even longer, the volume and intensity of daily physical activity among youth have gradually declined.

• Given the large proportion of total waking hours spent at school and in school-related activities, remarkably little is known about students’ physical activity behaviors during school hours and during school-related after-school activities. Despite some excellent research and a few good public health surveillance systems, current monitoring of overall and school-related physical activity behaviors among

youth and school-related policies and practices that enable or impede those behaviors is inadequate.

• An adequate description of the current status of and monitoring of changes in students’ school-related physical activity behaviors currently is not possible. Public health and education surveillance and research need to be enhanced so that the impact of efforts to increase students’ physical activity can be monitored.

• Policies are and will be important in creating an atmosphere in schools that enables, facilitates, and encourages children to be more physically active. Less clear are the factors that create an effective policy. An understanding is needed of what facilitators (e.g., funding, promotions, awards) and enforcers (e.g., less funding, job security) lead to policies that are fully implemented.

As discussed in further detail throughout this chapter, few children in the United States, probably no more than half, meet the currently recommended standard of at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity daily (CDC, 2012b). In addition, the proportion meeting the standard declines with age, with more elementary school children than middle and high school students achieving the goal. Boys are more likely than girls to meet the recommendation. Finally, it can be said with reasonable certainty that during the past 30-40 years, probably even longer, the volume and intensity of daily physical activity among youth have gradually declined.

It is also known that because children and adolescents spend so many hours at school, school-related physical activity must be a large contributor to overall physical activity among youth. Not known, however, is exactly how large the overall contribution is or the contribution of each segment of the school day—transportation to and from school, physical education, recess, classroom time, and before- and after-school activities. It is known that over the past 40 years the proportion of children walking and biking to school has declined substantially; otherwise, there are at best rough estimates of the current physical activity behaviors, recent changes, or long-term trends associated with each of these segments of the school day.

Guidelines, recommendations, and policies from all levels of government (federal, state, district, local) and from various organizations (e.g.,

National Association for Sport and Physical Education, American College of Sports Medicine) are known to influence youth’s school-related physical activity. Understood as well is that the strength of that influence is, in turn, affected by incentives and enforcements associated with those guidelines, recommendations, and policies (see Figure 1-3 in Chapter 1). What remains unclear is which guidelines, recommendations, policies, incentives, and enforcements are most influential in today’s social milieu.

What should also be apparent is that, despite some excellent research and a few good public health surveillance systems, current monitoring of overall and school-related physical activity behaviors and school-related policies and practices that enable or impede those behaviors is inadequate. These deficiencies have arisen for several reasons. First, physical activity has only recently been acknowledged as a vital public health issue, so monitoring of the volume of physical activity at the population level is a recent objective with still insufficient priority. The Physical Activity and Health Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was not established until 1996, and the first formal federal-level physical activity guidelines were not published until 2008 (HHS, 2008). Second, physical activity is a notoriously difficult behavior to measure. Third, understanding of the types and amounts of physical activity relevant to health and health outcomes is still growing. The types and amounts of physical activity recommended for children and adolescents have changed several times in the past 20 years, frustrating efforts to monitor trends. Fourth, information is scarce on prevalence and trends for policies that may enable (or inhibit) physical activity. Examples include school- and district-level policies on recess and training for physical education teachers, as well as community or neighborhood policies on active transport to and from school. Monitoring of policies and practices is improving but needs expansion and maturation. Finally, schools and school districts vary greatly in size, resources, environmental setting, urbanization, population characteristics, traditions, and policies. Summary assessments and measures may capture the national gestalt but omit important differences among subgroups.

Physical Activity Versus Exercise

Physical activity is defined as all human movement; it is done at some rate of energy expenditure in all settings and for many different purposes. Exercise is a subcomponent of physical activity that is done for the purpose of increasing physical fitness. Intensity (i.e., rate of energy expenditure) is an important descriptor of physical activity because different intensities have different physiologic effects. Both physical activity and exercise encompass the full range of energy expenditure.

The purpose of this chapter is to describe the evidence supporting these general statements about the status and trends of the physical activity behaviors of school-age children and adolescents, as well as the school-related policies and practices that help determine those behaviors. Description of the status and trends of physical activity behaviors of youth requires, along the way, some discussion about the behaviors themselves, how they are measured, and how the current recommendations came into being.

Unless they take a nap or lie down to rest, all people are physically active from the time they get up in the morning until they go to bed at night. Physical activity is a necessary part of everything people do at home, work, or school; while going from place to place; and during leisure time. Few people in the United States, whether adults or children, expend a great deal of energy during physical activity, but they are always expending some. In the still-emerging field of physical activity and public health, physical activity is commonly defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure” (Caspersen et al., 1985, p. 126). Despite this straightforward definition, physical activity is a complex behavior with a wide variety of types and intensities. Types of physical activity may be categorized, for example, by type of movement (e.g., walking, skipping), by sport (e.g., soccer, badminton), by life context (e.g., at school, at home, during transportation), or by predominant physiologic effect (e.g., cardiorespiratory conditioning, muscle strengthening). Regardless of the categorization scheme, physical activity operates through multiple physiologic pathways to influence many health outcomes. Although physical activity can be categorized and discussed in many ways, aerobic activities are the most common and have the broadest physiologic and health effects. Aerobic activities are commonly categorized as being of sedentary, light, moderate, or vigorous intensity based on the rate of energy expenditure (see Box 2-1).

STATUS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY BEHAVIORS AMONG YOUTH

This section reviews what is known about the status of physical activity behaviors among youth, first for vigorous- or moderate-intensity activity, next for sedentary or light-intensity activity, and finally for vigorous- or moderate-intensity activity during the school day.

Vigorous- or Moderate-Intensity Physical Activity

Vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity is important for normal growth and development (see Chapter 3), including maintenance

BOX 2-1

Categories of Intensity of Physical Activity

Categories of Absolute Rate of Energy Expenditure

Aerobic activities are common and important. Such activities include walking, dancing, and playing soccer or basketball, all of which involve large muscle groups in rhythmic repetitive movement. Aerobic activities are performed at a pace that can be continued for more than a few minutes, and when done at higher-than-usual levels, improve the efficiency and capacity of the cardiorespiratory system (Powell et al., 2011).

Aerobic activities have commonly been categorized based on the rate of energy expenditure, or intensity, at least in part because high rates of energy expenditure were known to be important for fitness training and were presumed necessary to reduce the risk of heart disease. Although energy expenditure can be measured in various units (e.g., kilocalories, milliliters of oxygen consumption), metabolic equivalents (METs) have become the method of choice in public health circles. One MET is the rate of energy expenditure while a person is at rest and is equivalent to an oxygen uptake of about 3.5 ml/kg body weight × min. Because METs take a person’s body weight into account, the MET rate for any given activity is similar for all individuals. For adults, for example, the MET rate while sitting at rest is 1.0, for cooking or food preparation is 2.0, for walking at 3 miles per hour is 3.5, and for running at 5 miles per hour is 8.3. Because of their smaller size, immature motor patterns, and other physiologic differences, children’s energy expenditure for most activities is slightly higher than that for adults (Torun, 1983). Despite these differences, adult MET values provide the best approximation of energy expenditure for children for most activities. The exceptions are walking and running, for which equations based on age and speed should be used (Ridley et al., 2008).

Although rate of energy expenditure is a continuous variable, splitting the range into four categories has become standard (Pate et al., 2008) (see the table on the next page). This categorization scheme has facilitated conversation, epidemiologic analysis, surveillance, and public health recommendations. Although useful, the scheme and its arbitrary

cut-points have become rigid, obscuring the fact that rate of energy expenditure is a continuous variable and cut-points are arbitrary.

Categories of Intensity of Physical Activity

| Category | Range of Metabolic Equivalents (METs) | Examples of Activities |

| Sedentary Activity | ≤1.5 METs | Sleeping, lying down, sitting, watching television |

| Light-Intensity Activity | >1.5-<3.0 METs | Standing; walking slowly; everyday activities such as getting dressed, making a bed, cooking |

| Moderate-Intensity Activity | ≥3.0-<6.0 METs | Walking, table tennis, ball-room dancing |

| Vigorous-Intensity Activity | ≥6.0 METs | Running at various speeds, shoveling snow, mowing the lawn while walking with a hand mower |

of healthy body composition, and reduces the likelihood of acquiring risk factors for the development of chronic diseases later in life. The currently recommended dose of physical activity for children and adolescents is at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per day, with vigorous physical activity on at least 3 of those days (Strong et al., 2005; PAGAC, 2008).

In 2005 a panel was convened by the CDC specifically to consider the physical activity needs of children and adolescents (6-18 years of age). The

Relative Rate of Energy Expenditure

The rate of energy expenditure expressed in METs, kilocalories, or kilo-joules is an absolute measure of intensity. For all people, higher rates of energy expenditure require a greater level of effort, and the above categorical terms for the commonly used categories—sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous—reflect that fact. For most healthy and reasonably fit youth and adults, the categorical terms and the individual’s perceived level of effort closely align. Older and unfit persons, however, require a greater relative, or perceived, level of effort to accomplish a given physical activity (see the table below). For example, a healthy person with the capacity to expend energy at a rate of 12 METs feels as though he or she is performing vigorous activity when jogging (MET level above 7), whereas an older or unfit person with a capacity of only 5 METs feels as though he or she is performing vigorous activity when walking (MET level of 3-4). Recognizing that level of fitness determines the rate of energy at which physical activity can be performed is important when planning programs to improve the fitness of any individual or group.

Relative Intensity of Activity for Younger and Fit Persons and for Older and Unfit Persons

| Relative Intensity | Younger and Fit (12 MET capacity) | Older and Unfit (5 MET capacity) |

| Light | <3.2 METs | <1.8 METs |

| Moderate | 3.2-7.5 METs | 1.8-3.3 METs |

| Vigorous | ≥7.6 METs | ≥3.4 METs |

| SOURCE: Adapted from Table D-1 in PAGAC, 2008. | ||

panel reported beneficial effects of regular physical activity on muscular health, cardiovascular health, adiposity, blood pressure, blood lipid levels, self-concept, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and academic performance. The optimal dose was more difficult to determine for at least two reasons (see also Box 2-2). First, different health outcomes accrue from different doses. Second, research demonstrates a positive dose response rather an ideal dose. The panel concluded, however, that “school-aged youth should participate every day in 60 minutes or more of moderate to vigorous physi-

BOX 2-2

Dose of Physical Activity

The dose of physical activity, sometimes referred to as volume or amount, is a function of the type, frequency, duration, and intensity of the activity. Until recently, benefits appeared to derive almost exclusively from vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, and almost all epidemiologic, clinical, and intervention research focused on that intensity range. Evidence derived from that research indicated that, for both adults and youth, health benefits are more closely related to the total dose of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity than to any of the components of dose (i.e., type, frequency, duration, intensity) (PAGAC, 2008). Research has consistently demonstrated an inverse relationship between the dose of regular vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity and a wide variety of adverse health outcomes (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, functional limitation, depressive symptoms) (PAGAC, 2008).

Dose of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity has been measured in a variety of ways, including minutes per week, kilocalories or kilojoules of energy expenditure, or even miles or minutes of running per week. A method frequently used to describe the dose of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity is to multiply the time spent in the activity by its metabolic equivalent (MET) value (see Box 2-1). For example, running at 5 miles per hour (about 8 METs) for 20 minutes provides a dose of 160 MET minutes.

Accelerometers permit estimates of the total dose of physical activity performed in a day regardless of intensity (see also Box 2-3). By estimating intensity for every minute, accelerometers can provide an estimate of the total dose of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. Accelerometers are not yet able to “know” exactly what type of physical activity is being performed (e.g., cycling, stair climbing, raking, sweeping) and as a result may over- or underestimate the rate of energy expenditure. Nevertheless, the products are improving rapidly, and their capability to measure sedentary and light-intensity as well as vigorous- or moderate-intensity activities makes them an increasingly valuable tool.

The inverse relationship between dose of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity and reduced risk of adverse health outcomes clearly demonstrates that larger doses provide more health benefits. Selecting a single dose to recommend has been more difficult, especially for youth,

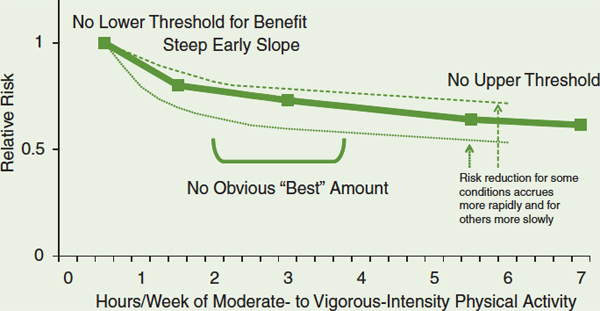

because less research is available on this question, and the pattern of the dose-response curve is less well established (PAGAC, 2008). A composite of the findings for adults from 10 studies of regular physical activity and all-cause mortality indicates a curvilinear relationship, with the risk of mortality decreasing as the dose of regular vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity increases (PAGAC, 2008; Powell et al., 2011) (see the figure below). Four points are worth noting about the dose-response curve. First, there is no lower threshold for benefit; some vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity is preferable to none. Second, the slope is steepest at the left side of the curve, suggesting that the most rapid reduction in risk occurs when the least physically active people become slightly more active. Third, there is no obvious best dose, making a range of doses (e.g., 150-300 minutes per week of vigorous-or moderate-intensity physical activity for adults) as in the current U.S. guidelines (PAGAC, 2008) preferable to a single dose. Fourth, at levels of activity commonly achieved in the general population, there is no upper threshold above which risk ceases to decline, although the rate of decline decreases.

Risk of all-cause mortality by hours per week of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity.

SOURCE: Adapted from PAGAC, 2008.

The available evidence indicates that the dose-response curves for the beneficial effect of regular vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activ-

ity on the risk for type 2 diabetes, hip fracture, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, depression, dementia, breast cancer, and colon cancer are similarly shaped (PAGAC, 2008) but with slightly different slopes (Powell et al., 2011); insufficient data are available with which to prepare similar dose-response curves for other health outcomes. Risk reduction accrues more rapidly for diabetes and hip fracture and less rapidly for breast and colon cancer. Risk reduction for cardiovascular disease, depression, and dementia appears to be quite similar to the curve for all-cause mortality. These differences are not surprising given the wide variety of physiologic pathways through which regular physical activity produces its various health benefits. The shape of the dose-response curve and the differences in the slopes of the curves for different health outcomes demonstrate the difficulty of identifying a specific dose or even a range of doses of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity that should be recommended.

cal activity that is enjoyable and developmentally appropriate” (Strong et al., 2005, p. 736). In 2008 the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee also reviewed the scientific evidence relating to physical activity and the health of children and adolescents (PAGAC, 2008). That committee confirmed the benefits reported by the previous panel. The committee also agreed that it is difficult to select a minimal or optimal dose of physical activity for youth but reaffirmed the recommendation for 60 minutes or more per day of vigorous or moderate physical activity. The committee further commented that weekly activity should include some vigorous activity on at least 3 days and some activities to strengthen muscles and bones.

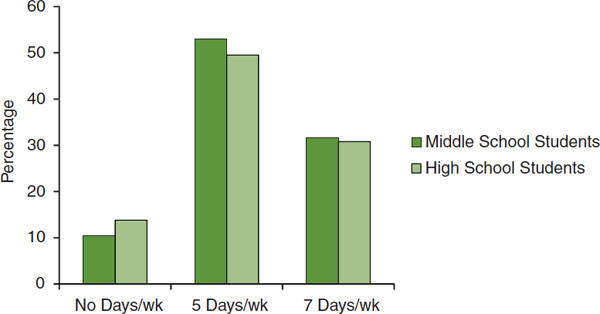

Available information indicates that relatively few youth achieve a daily dose of at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. Information on the proportion of youth who are vigorously active on 3 or more days per week is not available. However, about 10 percent of middle and high school students responding to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), conducted by the CDC and state health departments, self-reported that on no days in the previous week did they spend at least 60 minutes doing vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, about 50 percent reported doing so on at least 5 days, and about 30 percent

reported meeting the recommended 7 days (CDC, 2012b) (see Figure 2-1). In a different ongoing national survey of 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students—Monitoring the Future—fewer than half of students reported doing 60 or more minutes of vigorous activity every or almost every day (Delva et al., 2006).

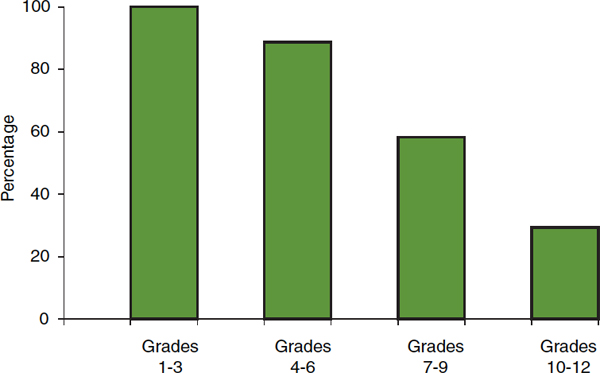

Results from surveys measuring physical activity with accelerometers and including younger children similarly suggest that few children, especially older ones, meet the currently recommended volume of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. A study of accelerometer-measured physical activity among students in central Massachusetts found that almost all students in grades 1-6, but fewer than one-third of high school students, performed at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity at least 5 days per week (Pate et al., 2002) (see Figure 2-2); the proportion of students meeting the 7-day recommendation would, of course, be lower. Also worth noting is that for high school students in this study, the accelerometer-estimated prevalence is about half the self-reported estimated prevalence for the same dose among students responding to the YRBS (see Figure 2-1). (See Box 2-3 on measuring physical activity.)

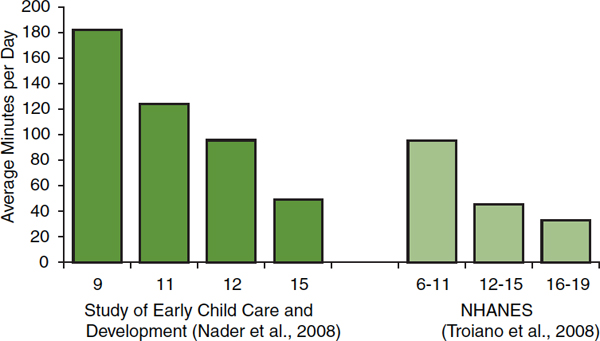

Results of other surveys confirm the decline in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity with age (Nader et al., 2008; Troiano et al., 2008). Figure 2-3 displays the mean number of minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per day rather than the proportion who

FIGURE 2-1 Percentage of middle and high school students reporting they engaged in no days, 5 days, or 7 days per week of 60+ minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity.

NOTE: The middle school estimate is the mean of 15 statewide surveys; the high school estimate is based on a nationwide sample.

SOURCE: CDC, 2012b.

FIGURE 2-2 Percentage of students performing accelerometer-measured vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity for at least 60 minutes on at least 5 days per week, by grade.

SOURCE: Adapted from Pate et al., 2002.

BOX 2-3

Measuring Physical Activity

Physical activity has been measured in multiple ways—self-reported measures (e.g., surveys, activity logs); instrumental measures (e.g., pedometers, accelerometers), often called “objective” measures; and direct observation—none of which are completely satisfactory.

Self-report surveys, in which youth are asked to provide information about their physical activity behaviors, have been the most common method of measurement. They vary considerably in the detail requested and obtained. For example, the 3-Day Physical Activity Recall (3DPAR) asks about the predominant activity performed (a list of likely options is provided) and the intensity of that activity (light, moderate, hard, very hard) during each of 34 30-minute segments between 7 AM and midnight (Pate et al., 2003). The 3DPAR has been used with children as young as 5th grade (Powell et al., 2009) but understandably has been used largely as a research tool. In contrast, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS),

used to monitor a number of important health-related behaviors of youth, currently asks the following question: “During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day? (Add up all the time you spent in any kind of physical activity that increased your heart rate and made you breathe hard some of the time.)” Self-reported data have been and will remain important. It is relatively inexpensive to obtain and can provide information about what specific activities were performed, as well as where and why. The YRBS, for example, inquires about participation in physical education classes and on sports teams. Self-reported information also has important limitations and weaknesses. Readers might try asking themselves the above question about physical activity during the past 7 days to realize how difficult it is to provide an accurate response. High school students likely are better than middle school students at answering such conceptually complex questions, and the questions as asked would be inappropriate for elementary school students—self-report has been discouraged as a mode of physical activity assessment for children less than 10 years old (Kohl and Hobbs, 1998). Moreover, even though students appear to answer personally sensitive questions (e.g., about their sexual behaviors) frankly, self-reported information is at risk of bias due to social acceptability and level of knowledge and experience. Self-reported data also are much more accurate for vigorous-intensity than for moderate- and light-intensity activities and generally overestimate the amount of vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity performed. Further, some studies have asked parents to provide information on the physical activity behavior of elementary-aged youth. The accuracy of parent proxy reports of children’s physical activity behavior has not been established.

Instrumental monitors, such as pedometers and accelerometers, provide more objective assessments of physical activity and are being used with increasing frequency. Pedometers and accelerometers, about the size of a watch, usually are attached at hip level to a belt or other article of clothing. Participants are instructed to wear them during waking hours for several days, often a week, except when bathing or swimming. Pedometers detect the vertical force associated with each step, and the output (number of steps taken) is reasonably straightforward. Accelerometers are more complex. They record the force of movements in up to three directions, and as they have become more sophisticated, require more complicated software to download and process the raw

data. The instruments avoid the subjective weaknesses of self-reported data but have their own problems. First, they must be properly calibrated to assess the existence and force of any movement. Moreover, accelerometers are reasonably good at detecting and quantifying common ambulatory movements (e.g., walking, running) but are not as good for stair climbing; cycling; water activities; or activities primarily of the upper body, such as sweeping or raking. In addition, the instruments cannot determine exactly what activity is being done, where, or why. The cut-points used to place movements in the common intensity categories (sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous) also may over- or underestimate the volume of activity depending on the predominant physical activity behaviors of the subjects under investigation (Matthews et al., 2008; Troiano et al., 2008), and they cannot assess relative intensity. Still, instruments measuring physical activity continue to improve and are becoming less costly, and they are useful across the full age spectrum. They appear to be the best method for collecting information about activities in the low and middle ranges of rate of energy expenditure and are expected to become even better with more research and experience.

Direct observation can be carried out with a number of reliable and valid tools (e.g., System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time [SOFIT], System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth [SOPLAY], System for Observing Play and Relationships in Communities [SOPARC]) developed to allow one or multiple observers to capture physical activity levels of youth across various settings and activities, such as physical education classes, recess, or leisure play in neighborhood settings (e.g., parks) (McKenzie et al., 1991). Observations capture information on sedentary (e.g., lying down or sitting), moderate-intensity (e.g., walking), and vigorous (e.g., running) physical activity behaviors from a sample of study participants. The observer can also record what activity is being done, where, and why. Some observation instruments also allow additional contextual information to be collected, such as social groups and social behavior during activities (System for Observing Children’s Activity and Relationships during Play [SOCARP]). Direct observation also has limitations, however: it is expensive, observers who collect the data must be trained in the use of the instruments, a sample of study participants rather than a census is observed, and observers must be physically present or capture the entire area on video for later review.

FIGURE 2-3 Average minutes/day of accelerometer-measured vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity by years of age and source.

NOTE: NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

SOURCES: Nader et al., 2008; Troiano et al., 2008.

do or do not achieve a set number of minutes, as presented in Figures 2-1 and 2-2. These three figures illustrate some of the difficulties entailed in comparing studies that used different measurement methods (i.e., self-report versus accelerometer-measured) and different types of data summary (i.e., proportion meeting a specific standard versus average of the whole group).

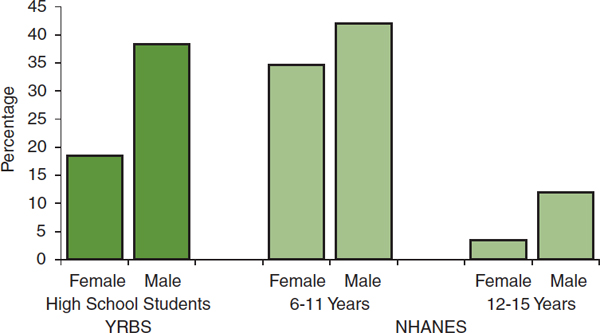

In addition to the low proportion of children and adolescents meeting currently recommended physical activity levels and the decline in vigorous-or moderate-intensity physical activity with age, data from the above and other surveys indicate, almost without exception, that girls are less active than boys (see Figure 2-4). Patterns of activity by race/ethnicity are less clear. Large surveys (e.g., YRBS, Monitoring the Future) using self-reported information usually find that whites report more vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity than other racial/ethnic groups (Simons-Morton et al., 1997; Delva et al., 2006; CDC, 2012a). In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), however, in which physical activity is assessed using accelerometers, non-Hispanic blacks are the group with the most vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity (Troiano et al., 2008; Gortmaker et al., 2012). In a study of 6th-grade girls from six states, also using accelerometers to assess physical activity, white girls had the highest average number of minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, while African American girls had the highest prevalence of meeting physical activity recommendations (Pate et al., 2006b). An

FIGURE 2-4 Percentage of youth reporting at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity daily by sex: self-reported estimates from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (2011) and accelerometer estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (2003-2004).

SOURCES: Troiano et al., 2008; CDC, 2012b.

analysis of youth aged 12-19 who performed treadmill tests as part of the NHANES found that about one-third of subjects failed to meet standards for cardiovascular fitness, but there were no significant differences in the prevalence of acceptable cardiovascular fitness among non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Mexican American subjects (Pate et al., 2006a). Physical fitness and physical activity are different but directly related concepts. Finding no differences in cardiovascular fitness among groups suggests that there also are no differences in overall amounts of vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity.

Fewer data are available with which to assess the influence of socio-economic status on physical activity behaviors, and these data, too, provide no clear picture. Proxy information from the NHANES for children aged 6-11 indicate that a higher proportion from low-income than from high-income families meet current recommendations for vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity (Fakhouri et al., 2013). Self-reported information from children 9-13 years of age and their parents shows a slightly lower percentage (74 percent) of children from low-income (≤$25,000/year) than from high-income (>$50,000/year) families (78 percent) engaging in free-time vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity (CDC, 2003). This same survey did find that substantially fewer children from low-income (24 percent) than high-income (49 percent) families participate in organized physical activities because of transportation problems, expense, and lack of opportunities.

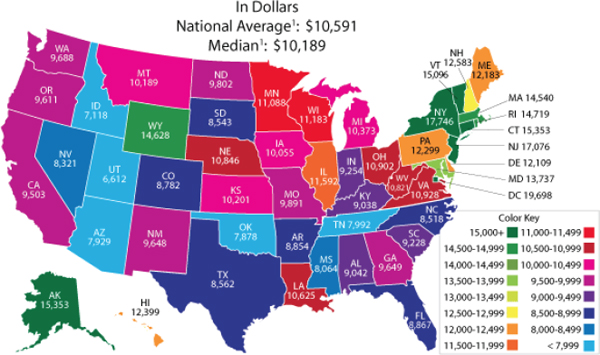

Despite limited information about differences, if any, in physical activity behaviors among racial/ethnic or socioeconomic groups, information about the variability of funding among school districts across the United States suggests that not all students have equal opportunities for participating in physical activity during the school day. Schools are funded by local and state governments, as well as the federal government. During the past 50 years, local and state governments have each provided about 45 percent of school funding, with the federal government providing about 10 percent. Considerable variation exists, however, among states and school districts in per-pupil expenditures for elementary and secondary education and in the sources of the funds.

In the 2008-2009 school year, per-pupil expenditures ranged from $6,612 in Utah to $19,698 in the District of Columbia (see Figure 2-5). The source of those funds also varied markedly among states. The federal portion of annual expenditures ranged from 4 percent in New Jersey to 16 percent in South Dakota (New America Foundation, 2012). The proportion of

FIGURE 2-5 Per pupil expenditures for public elementary and secondary education in the United States, 2008-2009.

1U.S. estimates are for the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

NOTE: The prekindergarten student membership was imputed for some states, affecting the total student count and calculation of per pupil expenditures. Some values were affected by redistribution of reported expenditure values to correct for missing data items and/or to distribute state direct support expenditures.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, 2009.

state funding, mainly from income and sales taxes, ranged from 86 percent in Vermont to 28 percent in Illinois; local funding, mainly from property taxes, ranged from 60 percent in Nevada to 3 percent in Hawaii.

Substantial within-state variation in per-pupil expenditures also exists. A general assumption is that the quality of education is directly linked to the quantity of funding. However, different systems have different levels of efficiency, and living costs and workforce salaries vary among and within states. In addition, educating children from low-income homes, those with disabilities, or those for whom English is a second language costs more. Various methods have been proposed for comparing funding levels among different school districts, including simple dollar-to-dollar comparisons; cost-of-living adjustments; and “level-of-effort” adjustments, such as proportion of total taxable state and local resources or state per capita gross domestic product (Epstein, 2011).

While the best way to measure and resolve differences in educational opportunities among and within states is uncertain, it is clear that substantial differences exist. Children and adolescents from low-income families are more likely to live in low-income school districts and have fewer resources for public education. It appears likely that fewer resources for education systems result in fewer opportunities for school-related physical activity. As noted above, however, information about the differences in physical activity behaviors among different racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups is sparse and inconsistent.

Sedentary or Light-Intensity Physical Activity

Recent evidence indicates that light-intensity physical activity, although not likely a substitute for vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, is beneficial to health. Research has focused on the detrimental health impact of sedentary-intensity physical activity, usually sitting or watching television, but the evidence can just as well be described as showing benefits from light-intensity physical activity (see Box 2-4). The relative merits of different levels and combinations of physical activity intensities are being investigated and discussed, but the lower end of the spectrum of rate of energy expenditure is now receiving attention previously reserved for the higher end.

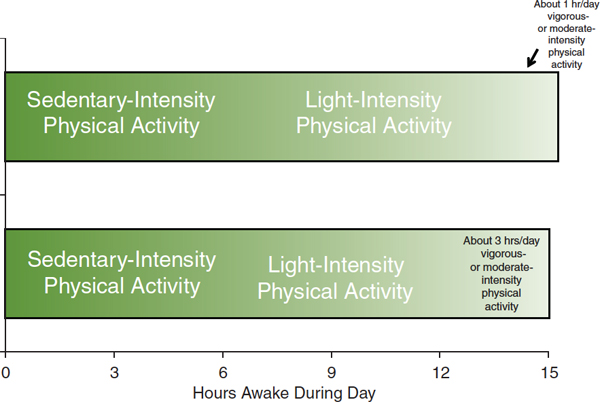

An important aspect of sedentary-intensity physical activity is the large portion of waking hours it fills. Assuming about 15 hours per day of wakefulness, sedentary and light-intensity physical activities fill 80 percent of waking hours for youth who spend 3 hours doing vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activities (see Figure 2-6). For youth just meeting the 60-minute daily recommendation for the latter activities, the former would fill 93 percent of the day. For the majority of youth not meeting the

BOX 2-4

Recognizing the Value of Light-Intensity Physical Activity

Thirty to 40 years ago, only vigorous physical activity was thought to provide reductions in disease risk. By the early 1990s, however, it was clear that moderate-intensity physical activities were healthful, too. The joint Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommendations of 1995 formalized acceptance of the health benefits of moderate-intensity physical activity (Pate et al., 1995). Recognition that the benefits of regular physical activity did not require the effort, commitment, and skill of an athlete solidified the public health value of physical activity and has guided epidemiologic, intervention, and clinical research ever since. That outcome has been good. It led, however, to a rigid categorization of physical activity into the good (vigorous- or moderate-intensity) and the bad (sedentary or light-intensity). In some scientific reports and even in official documents (PAGAC, 2008), “physical activity” has been used to mean vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. This usage has become common, making it difficult for many to accept emerging evidence for the health benefits of light-intensity physical activity.

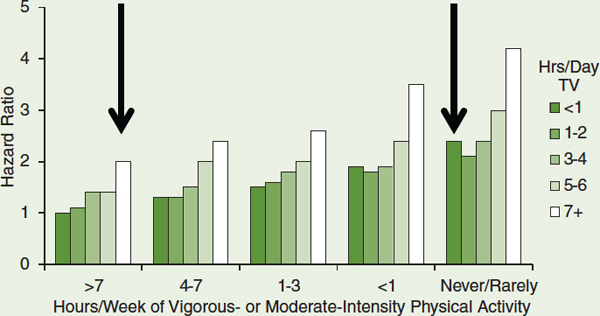

Recent research among adults indicates that replacing sedentary activities with light-intensity physical activity while holding the volume of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity constant provides health benefits (Hu et al., 2003; Healy et al., 2008a,b; Katzmarzyk et al., 2009; Wijndaele et al., 2010, 2011; Grøntved and Hu, 2011; Matthews et al., 2012). Data from a National Institutes of Health (NIH) and AARP study of more than 200,000 adults demonstrate that light-intensity physical activity augments the benefits of more intense physical activity (Matthews et al., 2012). At every volume of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, the risk of cardiovascular mortality increases as the volume of sedentary activity, assessed as hours of watching television, increases (see the figure on the next page). Worth noting is the essentially equivalent risk among those who do the most vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity and the most television watching and those who do no vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity and the least television watching (see the arrows in the figure).

Cardiovascular mortality by hours per week of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity and hours per day of television viewing.

SOURCE: Matthews et al., 2012. Reprinted with permission.

The health impact of sedentary-intensity physical activity among children and adolescents is likely the same. A qualitative review of 232 studies found a dose-response relationship between more sedentary behavior and unfavorable health outcomes, including unfavorable body composition, decreased fitness, lower scores for self-esteem and prosocial behavior, and decreased academic achievement (Tremblay et al.,

current recommendation for vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, nearly the whole day comprises sedentary and light-intensity physical activities (Treuth et al., 2012).

Various suggestions have been made about what aspects of youth’s sedentary physical activity should be avoided and monitored, including limiting television viewing to less than 2 hours per day, limiting television viewing to less than 3 hours per day, limiting computer use to less than 3 hours per day, and limiting total media time to less than 2 hours per day (see, e.g., the Healthy People 2020 objectives [HealthyPeople.gov, 2012]).

Not surprisingly, surveys and studies of sedentary behavior among children and adolescents have used various methods of data collection

2011). Cohort studies among youth that have controlled for vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity have yet to demonstrate a relationship between reductions in sedentary activity (which is the same as increases in light-intensity activity) and health or risk factor outcomes (Carson and Janssen, 2011; Ekelund et al., 2012).

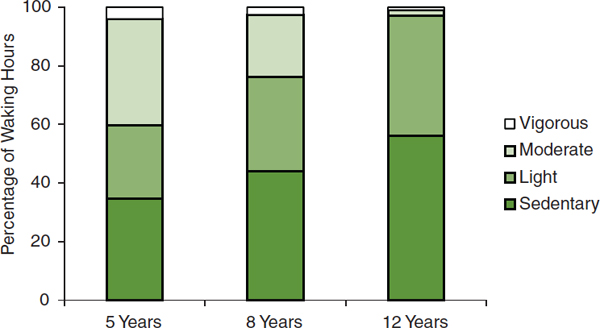

The implications of these findings for behavioral recommendations regarding beneficial physical activity are still under discussion. Sedentary activities fill about half the waking hours of children and adolescents (probably relatively less for children and more for adolescents). Sedentary and light-intensity activities together fill 80-95 percent of waking hours (see Figure 2-6). More remains to be learned about the differences in health improvement, academic performance, and classroom behavior engendered by different intensities of physical activity. It is clear that the physiologic effects differ for different intensities. Higher-intensity activities, for example, provide greater cardiovascular fitness and lower cardiovascular mortality risk at all volumes of sedentary activity. Most likely, different intensities provide different benefits. The current consensus is that children and adolescents need some vigorous activity daily for maximum current and future health. Light-intensity physical activity can now be viewed as a healthy shift away from sedentary physical activity as well. Higher rates of energy expenditure are preferred over lower rates across the full range of intensities. The behavioral differences between sedentary-intensity and vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activities are considerable, and interventions to discourage the former and promote the latter can be expected to be quite different.

(e.g., self-report, accelerometer, proxy), have assessed different aspects of sedentary-intensity physical activity (e.g., total sedentary time, watching television for more than 2 or 3 hours), and have reported the data in different formats (e.g., percentage meeting a specified requirement, mean minutes of sedentary physical activity). Taken together, the results of these surveys and studies indicate that children and adolescents spend a great deal of time in activities requiring very low energy expenditure. The results also indicate that girls are more likely than boys and older adolescents are more likely than children to engage in these low-energy activities, although the differences are generally smaller than for vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity.

FIGURE 2-6 Approximate number of hours spent during the day at different levels of energy expenditure.

SOURCE: Treuth et al., 2012.

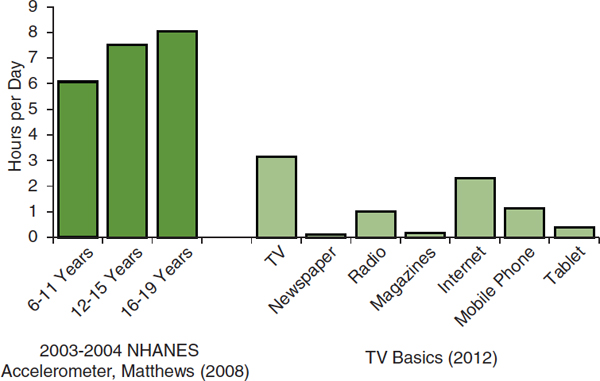

Data from the YRBS and the NHANES are the most frequently cited. Based on accelerometer-assessed physical activity, youth aged 6-19 engage in sedentary physical activity 6-8 hours per day (Matthews et al., 2008) (see Figure 2-7). Figure 2-7 also provides estimates of the average time per day spent using different types of media (TVB, 2012). Reports from the YRBS suggest that about one-third of both middle and high school students report watching television for at least 3 hours per day. In response to a different question, those in this age group (not necessarily the same students) report using a computer for at least 3 hours per day (CDC, 2012b). Other reports (Anderson et al., 2008; Sisson et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2009) and a review (Pate et al., 2011) are available. Data from two reasonably comparable studies demonstrate the reduction in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity and the rise in sedentary and light-intensity activity as girls grow from age 5 to 8 to 12 (Janz et al., 2005; Pate et al., 2006b) (see Figure 2-8).

FIGURE 2-7 Hours per day spent in sedentary activity by age group, ages 6-19, and hours per day using different media sources, ages 13-17.

NOTE: NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

SOURCES: Matthews et al., 2008; TVB, 2012.

FIGURE 2-8 Percentage of waking hours spent in sedentary, light, moderate, and vigorous physical activity by girls aged 5 and 8 (all from Iowa) and aged 12 (from Arizona; California; Louisiana; Maryland; Minnesota; South Carolina; and Washington, DC).

SOURCES: Janz et al., 2005; Pate et al., 2006b.

Vigorous- or Moderate-Intensity Physical Activity During the School Day

In the United States, elementary and secondary school students spend 180 days every year at school. On those days, about 6.5 hours, or about 40 percent of their waking hours, make up the official school day. Including time spent going to and from school and in school-related after-school activities, students spend half or more of the available hours of every school day at school or going to and from school. Given the large proportion of total waking hours spent at school and in school-related activities, remarkably little is known about students’ physical activity behaviors during school hours and during school-related after-school activities.

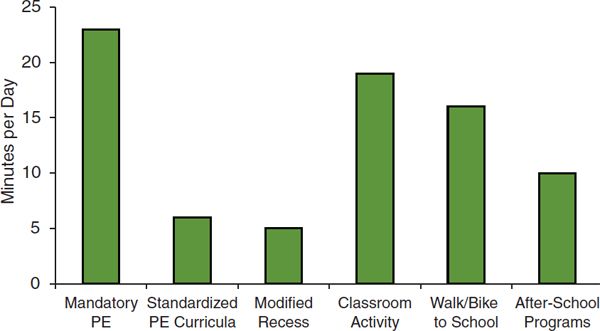

A recent analysis of the potential impact of select school-based policies indicates that the current dose of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity at school could be substantially increased (Bassett et al., 2013; see Figure 2-9; see also Chapter 7):

• Compared with no physical education, a usual physical education class adds about 23 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity to a student’s day.

• Using a standardized high-quality physical education program can add another 5 minutes. High-quality or enhanced physical education

FIGURE 2-9 Minutes per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity gained by implementing school-based policies.

NOTE: PE = physical education.

SOURCE: Bassett et al., 2013.

programs strive, among other things, to devote at least 50 percent of physical education time to vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity.

• Programs that enable and encourage more vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity during recess by providing age-appropriate equipment, blacktop games, and/or adult encouragement and supervision can add another 5 minutes.

• Inserting vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity into the classroom by incorporating physical activity into the lesson or by providing specific activity breaks can add about 19 minutes per day above the usual time.

• Walking or biking to school compared with being driven can add about 16 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity to the school day.

• After-school activity programs can add another 10 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per school day.

Despite evidence that policies and programs can increase vigorous-or moderate-intensity physical activity among children and adolescents on school days, only rough estimates are available, at best, of students’ baseline physical activity behaviors at school and during school-related activities. Therefore, only rough estimates can be made of the volume of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity that is being and could be achieved.

Physical Education

Children in elementary and middle school spend about 10-40 percent of their time in physical education classes engaged in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity (Simons-Morton et al., 1993, 1994; McKenzie et al., 1996; Sallis et al., 1997; Belsky et al., 2003; McKenzie et al., 2006). On average they have two physical education class periods per week, each for about 30 minutes (Belsky et al., 2003). Assuming that 35 percent of physical education time is spent in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity, children spend an average of 4 minutes per school day doing vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity in physical education classes (see Table 2-1). If elementary school students had 30 minutes of physical education daily (150 minutes per week) and middle school students had 45 minutes of physical education daily (225 minutes per week), the estimated number of minutes per day spent doing vigorous-or moderate-intensity physical activity during physical

TABLE 2-1 Estimated Current and Potential Minutes of Vigorous-or Moderate-Intensity Physical Activity on School Days for Physical Education, Classroom Physical Activity, Recess, Total School Hours, Active Transport, and After-School Sports and Activity Programs for Elementary, Middle, and High School Students

| Physical Education | Estimated Current Minutes | If Daily Physical Education (min) | If Enhanced Daily Physical Education (min) |

| Elementary | 4 | 11 | 15 |

| Middle | 4 | 16 | 23 |

| High | 4 | 16 | 23 |

| Classroom Physical Activity | Estimated Current Minutes | If Enhanced Classroom Activity (min) | |

| Elementary | ? | ≥19 | |

| Middle | ? | ≥19 | |

| High | ? | ≥19 | |

| Recess | Estimated Current Minutes | If Enhanced Recess (min) | |

| Elementary | 9 | 14 | |

| Middle | 9 | 14 | |

| High | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| Total School Hours | Estimated Current Minutes | If Daily Physical Education (min) | If Enhanced Daily Physical Education, Classroom Activity, and Recess (min) |

| Elementary | ≥15 | ≥21 | ≥49 |

| Middle | ≥15 | ≥26 | ≥57 |

| High | ≥ 5 | ≥21 | ≥42 |

| Active Transport (walking/biking) | Estimated Current Minutes | If Proportion of Students using Active Transport Doubled (min) | |

| Elementary | 2 | 4 | |

| Middle | 2 | 4 | |

| High | 1 | 3 | |

| After-School Activity Programs | Estimated Current Minutes | If All Students Participated (min) | |

| Elementary | ? | ≥10 | |

| Middle | ? | ≥10 | |

| High | ? | ≥10 | |

SOURCES: Simons-Morton et al., 1993, 1994; McKenzie et al., 1996, 2006; Sallis et al., 1997; Belsky et al., 2003; Ridgers et al., 2005; Delva et al., 2006; Tudor-Locke et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007; Fairclough et al., 2012; Gauthier et al., 2012; Rush et al., 2012; Bassett et al., 2013.

education would increase to 11 minutes and 16 minutes, respectively. If the proportion of time in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity during physical education were increased to 50 percent through the use of standardized high-quality physical education programs, the average time per day would increase to 15 minutes and 23 minutes for elementary and middle school students, respectively. High school students also average 2 days per week of physical education classes (Delva et al., 2006). If the proportion of time they spent in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity during physical education were assumed to be similar to that for primary school students, they would average 4 minutes per day currently, 16 minutes per day if they attended the classes daily, and 23 minutes per day if the classes were both daily and of high quality (see Table 2-1). These estimates are a bit lower than those in a recent analysis (Bassett et al., 2013).

Classroom Physical Activity

Information is insufficient with which to estimate the amount of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity in which an average student engages during usual instructional classroom time. As noted earlier, it is estimated that classroom physical activity could add 19 minutes of such activity to every school day (Bassett et al., 2013), perhaps at the primary and secondary school levels (see Table 2-1).

Recess

An estimated 97 percent of primary schools have regularly scheduled recess for about 30 minutes per day (Lee et al., 2007), and children spend roughly 30 percent of their time at recess doing vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity (Ridgers et al., 2005), for an estimated average time per day in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity during recess of 9 minutes. As noted, enhanced-quality recess (e.g., providing age-appropriate equipment, blacktop games, adult encouragement and supervision) could add an estimated 5 minutes (Bassett et al., 2013), for a total of 14 minutes per day (see Table 2-1).

Total During School Hours

The committee found few estimates of total vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity or step counts during school hours. The estimates it did find are from a limited number of schools and only one in the United States (Tudor-Locke et al., 2006; Fairclough et al., 2012; Gauthier et al., 2012; Rush et al., 2012). Together, these estimates suggest that about 40 percent of the usual volume of physical activity takes place during school hours, but no estimate of the total energy expenditure or time in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity was available. The estimates in Table 2-1 suggest that primary school students currently spend at

least 15 minutes per school day and high school students at least 5 minutes per school day engaged in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity during school hours. With high-quality daily physical education, enhanced-quality recess, and vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity inserted into usual classroom activities, the estimated minutes per school day would be at least 49, 57, and 42 minutes for elementary, middle, and high school students, respectively (see Table 2-1). These totals do not include vigorous-or moderate-intensity physical activity that might accrue during other parts of the school day, such as during the lunch break, or for the upper grades movement from one classroom to another.

Active Transport

Students who walk or bike to school average 16 minutes per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity during transit (Bassett et al., 2013). Currently, approximately 13 percent of primary school students, 11 percent of middle school students, and 8 percent of high school students usually walk or bike to school (McDonald, 2007; McDonald et al., 2011). Thus, the average minutes per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity during active transit for all students is 2 minutes for elementary and middle school students and 1 minute for high school students. Because many students live too far from school to be able to walk or bike (Falb et al., 2007; McDonald, 2007; McDonald et al., 2011), a doubling of the current prevalence of students using active transport is perhaps as much as could be expected without the creation of numerous smaller schools nearer children’s homes or major changes in school busing practices. The average number of minutes for all students would then increase to 4 minutes per day for elementary and middle school students and 3 minutes per day for high school students. Of course, for those students who can walk or bike to school, active transport provides the full 16 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity.

After-School Interscholastic and Intramural Sports, Physical Activity Clubs, and Other After-School Programs

Despite the growing popularity of these after-school activities, no good estimates of the number of participants exist. As noted earlier, after-school activity programs for elementary and middle school students are estimated to add 10 minutes per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity (Bassett et al., 2013).

TRENDS IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY BEHAVIORS AMONG YOUTH

This section reviews trends in physical activity behaviors among youth, examining in turn vigorous- or moderate-intensity activity, sedentary and light-intensity activity, and physical activity not necessarily related to school.

Vigorous- or Moderate-Intensity Physical Activity

Although estimates of children and adolescents currently achieving the recommended volume of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity vary depending on how the data were collected, it is clear that few children are sufficiently physically active. An important question is whether the current status of physical activity among youth is an improvement, a worsening, or no different relative to previous years. If the situation is improving (i.e., children have been becoming more active), no changes or new efforts may be warranted; if the situation is stable or worsening, actions are needed. Few data sources provide clear and convincing evidence on trends in children’s level of physical activity, but taken together the evidence is persuasive that children and adolescents in the United States have become increasingly less physically active over the past 40-50 years.

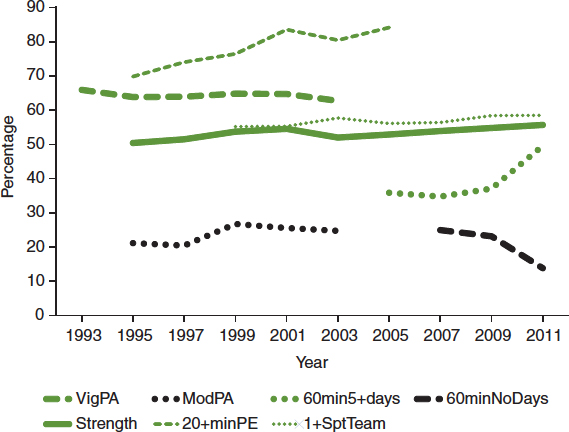

The YRBS provides self-reported information on physical activity among high school students for 1993-2011. Although the data span 20 years, trends in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity are obscured because the survey questions have been modified over time to align with changes in the recommended volume of physical activity for youth (annual surveillance reports from CDC’s website for 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011) (see Figure 2-10 and Box 2-5). The largest change is an increase from 70 percent in 1995 to 84 percent in 2005 in the percentage of students who participate in physical education and who report averaging more than 20 minutes per class exercising or playing sports. In 2011 there was a sharp increase over 2009 in the proportion of students reporting at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity on at least 5 days in the preceding week (37 percent to 50 percent) and a corresponding decline in the number reporting that much activity on no days of the preceding week (23 percent to 14 percent) (see Figure 2-10). These sharp changes are thought to be an artifact arising from a shift in the format of the questionnaire such that students had fewer opportunities to describe the types and amounts of their physical activity.

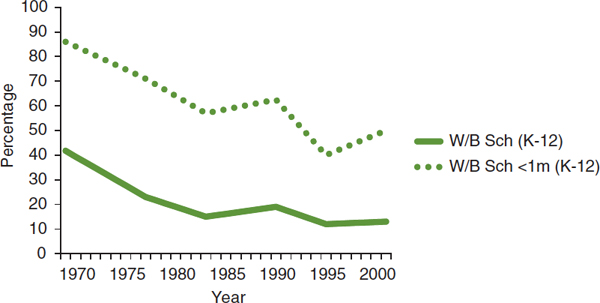

A clear example of a decline in physical activity among youth is the decrease in the proportion of schoolchildren walking or bicycling to school. Between 1969 and 2001, this proportion dropped from 42 percent to

FIGURE 2-10 Percentage of high school students meeting physical activity recommendations, doing strength training, playing on one or more sports teams, and engaging in 20 minutes or more of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity during physical education.

NOTES: VigPA = activities that caused sweating and hard breathing for at least 20 minutes on at least 3 of the 7 preceding days; ModPA = walked or biked for at least 30 minutes on at least 5 of the 7 preceding days; 60min5+days = physical activity that caused increased heart rate and hard breathing for a total of at least 60 minutes on at least 5 of the 7 preceding days; 60minNoDays = physical activity that caused increased heart rate and hard breathing for a total of at least 60 minutes on none of the 7 preceding days; Strength = activities such as push-ups, sit-ups, or weight lifting on at least 3 of the 7 preceding days; 20+minPE = among students who attended physical education classes, exercised, or played sports for more than 20 minutes during an average physical education class; 1+SptTeam = played on at least one sports team run by the student’s school or community groups during the 12 months before the survey.

SOURCE: CDC, 2012a.

13 percent; among children living within 1 mile of their school, it dropped from 86 percent to 50 percent (McDonald, 2007) (see Figure 2-11).

Sedentary or Light-Intensity Physical Activity

The above-noted evidence accumulated during the past decade indicating the health benefits of light-intensity physical activity compared with sedentary-intensity activities has spurred interest in monitoring trends in

BOX 2-5

Progression of the Recommended Dose of Physical Activity for Youth

The dose of physical activity recommended for youth has changed during the past 30 years (see the table below). Initially, with little information specific to youth available, the recommended dose for adults, children, and adolescents was the same. As knowledge accumulated and the special needs of children and adolescents were taken into account, the dose recommended for the latter age groups differed from that recommended for adults.

Changes Over Time in the Recommended Volume of Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents

| Year | Recommendation | Comment |

| 1985 | Vigorous physical activity for 20+ min/day on 3+ days/week | Same as recommendation for adults; activity should be continuous |

| 1995 | Vigorous physical activity for 20+ min/day on 3+ days/week or moderate physical activity for 30+ min/day on 5+ days/week | Same as recommendation for adults; activity can be accumulated during the day in 8- to 10-min bouts |

| 2005 | 60+ min/day of mainly vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity | Recommendation specifically for children and adolescents; activity should be varied, developmentally appropriate, and enjoyable |

Dose is the amount, or volume, of physical activity performed (see Box 2-2). For aerobic activities, dose is determined by the frequency, duration, and intensity of the activity. During the late 1970s and 1980s, the dose recommended for adults and children was 20 min or more of continuous vigorous activity on 3 or more days per week (HHS, 1984; ACSM, 1988). This recommendation, based largely on the dose required

for short-term training response in young adults (Simons-Morton et al., 1988), assumed that benefits were derived only from vigorous physical activity. By the mid-1990s, consensus had been reached that health benefits accrued from moderate-intensity physical activity as well, and the recommended dose was expanded to include either the dose of vigorous physical activity previously recommended or a dose of 30 min or more per day of moderate-intensity physical activity on 5 or more days per week (Pate et al., 1995; HHS, 1996). The dose of vigorous-intensity activity and the dose of moderate-intensity activity could be accumulated in segments as short as 8-10 min in length.

In 2005 a panel convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention specifically to consider the physical activity needs of children and adolescents (aged 6-18) recommended that “school-aged youth should participate daily in 60 minutes or more of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity that is developmentally appropriate, enjoyable, and involves a variety of activities” (Strong et al., 2005, p. 736). The 2008 report of the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, noting a direct relationship between the volume of physical activity in youth and cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, less adiposity among youth of normal weight, cardiovascular and metabolic health, bone mineral content and density, and several mental health outcomes, reiterated the value of 60 minutes or more of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per day for important health benefits (PAGAC, 2008). The committee further commented that weekly activity should include some vigorous activity on at least 3 days and some activities to strengthen muscles and bones.

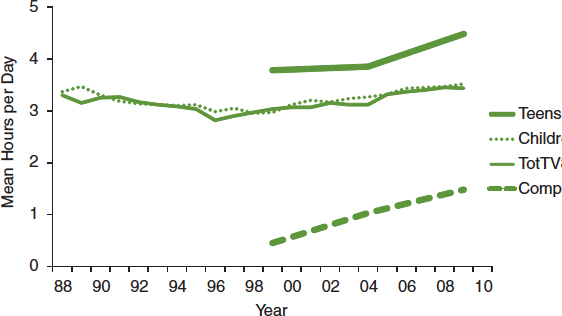

these two types of physical activity. One of the difficulties has been deciding which sedentary behaviors to monitor. Use of accelerometers in recent years has enabled researchers to measure total sedentary time, but long-term trends have depended on self-reported data, primarily regarding television viewing time and more recently also time spent watching videos, playing video games, and using a computer. Television viewing time has been monitored, often for business reasons, for a number of years. The average number of hours children and teens spent watching television daily declined

FIGURE 2-11 Percentage of students walking or bicycling to school.

SOURCE: McDonald, 2007.

slightly during the early 1990s, from about 3.3 hours per day to about 3 hours per day, and rose during the 2000s to about 3.4 hours per day (see Figure 2-12) (TVB, 2012). If television use includes DVDs, prerecorded shows, or television shows on other platforms (e.g., Internet, cell phone), then total television use has increased since the late 1990s, as has the use of computers for purposes other than schoolwork (Rideout et al., 2010). The prevalence of high school students reporting on the YRBS that they watched at least 3 hours per day of television declined from 38 percent in 2003 to 32 percent in 2011, while the prevalence of using computers for at least 3 hours per day increased from 21 percent in 2005 to 31 percent in 2011 (CDC, 2012a).

Physical Activity Not Necessarily Related to School

As noted, indirect and inferential evidence from several different types of research suggests that children and adolescents today are less physically active than previous generations. For example, comparisons with traditional cultures indicate a decline in routine physical activity. Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonite cultures eschew modern conveniences. Comparisons of accelerometer-measured routine physical activity among children from traditional Amish and Mennonite cultures and samples of U.S. and Canadian children indicate that the former children are more physically active (Tremblay et al., 2005; Esliger et al., 2010; Hairston et al., 2012). Children from Maryland’s Eastern Shore spent 53 minutes per day less in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity and 34 minutes per day less in light-intensity physical activity than the Old Order Amish children

FIGURE 2-12 Hours per day spent watching television by age group, 1998-2009, and hours per day spent watching television and using computers for youth aged 8-18.

NOTES: TotTV = total television content, which includes watching not only standard television programs but also prerecorded shows, DVDs, and television content on other platforms (e.g., Internet, cell phone, iPod); Comp = does not include time spent using a computer for schoolwork.

SOURCES: Rideout et al., 2010; TVB, 2012.

with whom they were compared (Hairston et al., 2012). This translates to 87 minutes per day of sedentary physical activity.

Declines in cardiorespiratory fitness among children around the world have been documented. American researchers usually have preferred not to compare current measures of cardiorespiratory fitness among American children with results of surveys from previous years because of differing measurement methods (Pate et al., 2006a), although one review has suggested declines since the 1960s (Malina, 2007). Assessments have been performed, however, in other countries using more consistent measurement techniques, and they indicate a global decline in cardiorespiratory fitness among youth (Santtila et al., 2006; Tomkinson and Olds, 2007; Albon et al., 2010; Boddy et al., 2012; Tomkinson et al., 2012) or, in one case, a decline in physical activity behaviors (Salmon et al., 2005) (see Table 2-2). A review of evidence from around the world found that participation by youth in “active transport, physical education, and organized sports is declining in many countries” (Dollman et al., 2005, p. 892). The authors also comment that “young people would like to be active but are constrained by external factors such as school policy or curricula, parental rules in relation to safety and convenience, and physical environmental factors” (p. 892).

TABLE 2-2 Declines in Physical Fitness Among Children Around the World

| Source | Location | Time Period | Age Range | Method of Assessment | Findings |

| Boddy et al. (2012) | United Kingdom | 1998-2010 | 9-10.9 years (cohort) | 20-m shuttle run | 1.8% decline per year |

| Tomkinson et al. (2012) | Asia (China, Japan, S. Korea, Singapore) | 1964-2009 | 9-17 years | Long-distance running time | 16% decline |

| Santtila et al. (2006) | Finland | 1975-2004 | 20 years | 12-min run | 8% decline |

| Albon et al. (2010) | New Zealand | 1991-2003 | 10-14 years | 550-m run | 1.6% decline per year |

| Salmon et al. (2005) | Australia | 1985-2001 | 9-13 years | Walking trips to school Taking physical education classes Participating in school sports | 17% decline 28% decline 11% increase |

| Tomkinson and Olds (2007) | 27 countries (varying time periods and age ranges) | 1958-2003 | 6-19 years | Various | 0.36% decline per year |

Finally, several studies provide empirical evidence for a gradual decline in physical activity among adults in occupational, transportation, and household tasks (Lanningham-Foster et al., 2003; Brownson et al., 2005; Church et al., 2011; Archer et al., 2013). Of interest, there is little evidence to suggest either a decrease or an increase in adult leisure-time physical activity. Although the evidence in these reports pertains to adult behavior, there can be little doubt that the declines in physical activity due to mechanization, technology, and social norms apply to children and adolescents as well.

STATE AND LOCAL POLICIES ON SCHOOL-BASED PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

As discussed in Chapter 1, schools are an important focal point for efforts to increase physical activity among children and adolescents. Accordingly, the committee examined the current state of knowledge on the

status of and trends in public policies regarding school-based physical activity. Public policies are an effective tool for influencing behavioral changes at the population level as opposed to the individual level, and have been shown to have significant long-term effects on population health and health behaviors. Examples include fluoridating drinking water and requiring the use of seat belts in motor vehicles (CDC, 1999). At present, there are no federal mandates on physical activity and physical education in schools. Therefore, this section presents the committee’s findings on state policies, including both statutory (legislative) and administrative (regulatory) laws, and school district wellness policies, as well as their implementation and effectiveness.

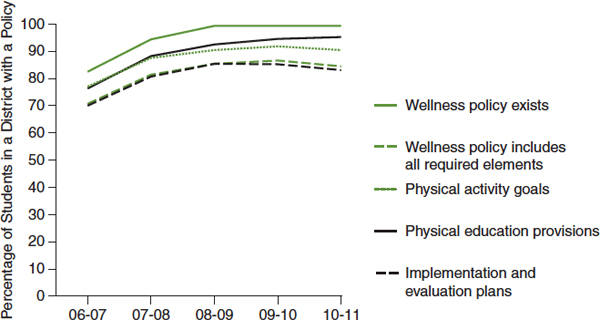

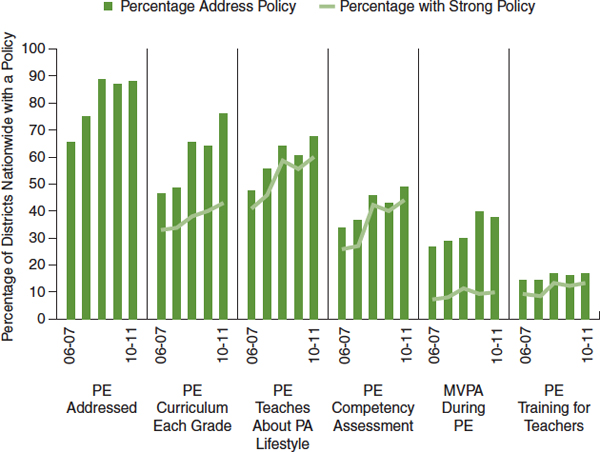

National surveillance systems contain quantitative data on the strength and comprehensiveness of these policies, developed using systematic and reliable coding systems. These data are useful for tracking both progress and changes in codified public policies of time and across jurisdictions.

Table 2-3 lists available sources of information on policies regarding school-based physical activity. The School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS; Burgeson et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2007) and the Shape of the Nation Report (NASPE and AHA, 2010, 2012) provide relevant policy information collected through self-report surveys; the National Association of State Boards of Education’s (NASBE’s) State School Health Policy Database supplements the SHPPS with additional information on the existence of relevant state laws and policies; and the National Cancer Institute’s Classification of Laws Associated with School Students (C.L.A.S.S.; Mâsse et al., 2007) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation–supported Bridging the Gap program (www.bridgingthegapresearch.org) compile state laws and then apply scoring systems to rank the laws in comparison with national standards and recommendations. Bridging the Gap also conducts the largest ongoing nationwide evaluation of the congressionally mandated school district wellness policies (Bridging the Gap, 2013b). The data on district wellness policies are coded using the same schemes as those used for state laws, thus enabling multilevel evaluations of the impact of district policies and state laws on school practices and student behaviors.

The SHPPS compiled information collected through self-report surveys for use in assessing school-based physical education and physical activity policies and practices at the state, district, school, and classroom levels. State-level data were collected from education agencies in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. District and school-level data were collected from nationally representative samples of public school districts and public and private elementary and secondary schools. Classroom-level data were collected from teachers of randomly selected classes.

The Shape of the Nation survey collects the following information on physical education: (1) time requirements; (2) high school graduation requirements; (3) exemptions/waivers and substitutions; (4) physical

TABLE 2-3 Data Sources for Policies Related to School-Based Physical Activity

| Data Source | Time Period | Method of Assessment | Levels |

| School Health Policies and Practices Study | 2000, 2006 | Self-report surveys, separate respondents for each level | State (census), district, school, classroom (nationally representative sample) |

| Shape of the Nation | Every few years from 1987 to 2012 | Self-report surveys, state physical education coordinators | State (census) |

| National Association of State Boards of Education’s State School Health Policy Database | Updated regularly since 1998 | Collection of laws and policies | State (census) |

| C.L.A.S.S. | 2003-2008, biennially starting in 2010 | Coded (scored) state laws | State (census) |

| Bridging the Gap | 2006-2012 | Coded (scored) state laws | State (census), district (nationally representative sample) |

activity; (5) local school wellness policy; (6) standards, curriculum, and instruction; (7) class size; (8) student assessment and program accountability; (9) body mass index (BMI) collection; (10) physical education teacher certification/licensure; (11) national board certification in physical education; and (12) state physical education coordinator requirements (NASPE and AHA, 2012).

The NASBE State School Health Policy Database, begun in 1998 and continuously updated (http://www.nasbe.org/healthy_schools/hs/index.php), provides a summary description of the most recent state-level laws, legal codes, rules, regulations, administrative orders, mandates, standards, and resolutions (see Appendix C for a summary table of the laws); it does not provide historical information on laws that were in place prior to 1998.

The C.L.A.S.S. and Bridging the Gap databases vary from the NASBE database by providing scores related to the strength of policies rather than the actual policy language. They also provide historical data by year, which allows for the examination of change in state laws over time. The C.L.A.S.S.

database contains state-level information in such areas as (1) physical education class time, (2) staffing requirements for physical education, (3) physical education curriculum standards, (4) assessment of health-related fitness during physical education, (5) physical activity time requirements outside of physical education, and (6) recess. C.L.A.S.S. uses a 0-4 or 0-5 rating scale, depending on the category, that captures information on the specificity, strength of language, and stringency of a law. Each year’s rating reflects laws in place as of December 31. Bridging the Gap, described in detail below, collects data on both state and school district policies related to physical education and physical activity and applies a 0-3 rating scale. All sources in Table 2-3 contain information on laws for elementary, middle, and high schools. All contain some duplicative information but also other measures that are unique to that source.

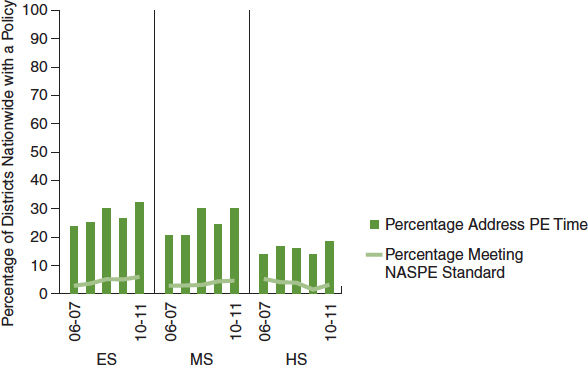

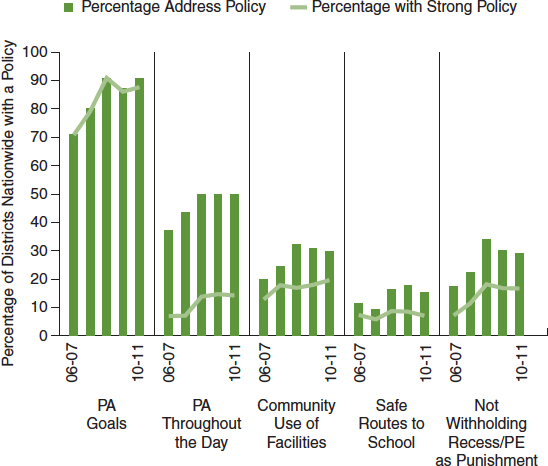

Given the overlap in these data sources, the following information on state- and school district-level policies was taken from two sources—one self-reported and the other objectively collected and coded. Tables 2-4 through 2-6 present trend data for 2000-2012 on the prevalence of state-level policies related to school-based physical education and physical activity. Table 2-4 presents information extracted from the SHPPS in 2000 and 2006 (Burgeson et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2007), while Tables 2-5 and 2-6 present information compiled from Bridging the Gap (Chriqui et al., in press). Starting with the 2006-2007 school year, Bridging the Gap has compiled policies for all 50 states and the District of Columbia annually from the state law databases Westlaw and Lexis-Nexis using keyword searches. All policies are coded using a 3-point rating scale, where 0 (none) represents those states with no policy, 1 (weak) represents states with a law that suggests/encourages or imposes a less stringent requirement than the

TABLE 2-4 Prevalence of Policies at the State, School District, and School Levels Related to School-Based Physical Education and Physical Activity, from the School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS)

| 2000 (%) | 2006 (%) | ||

| Physical | States requiring physical education | 78 | 80 |

| Education: | Districts requiring physical education | 83 | 78 |

| Elementary | Schools requiring physical education | (82) | 86 |

| Schools | • 3 days/week, all year, all grades | 25 | 14 |

| • daily, one-half year, all grades | 10 | 5 | |

| • daily, all year, all grades | 8 | 4 | |

| 2000 (%) | 2006 (%) | ||

| Physical | States requiring physical education | 86 | 93 |

| Education: | Districts requiring physical education | 85 | 90 |

| Middle | Schools requiring physical education | (89) | 89 |

| Schools | • 3 days/week, all year, all grades | 18 | 15 |

| • daily, one-half year, all grades | 16 | 15 | |

| • daily, all year, all grades | 6 | 8 |

|

| Physical | States requiring physical education | 82 | 93 |