HEALTH LITERACY WORK OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION

Jacob Kumaresan, M.D., Dr.P.H.

Executive Director, World Health Organization

Office at the United Nations in New York

This is a great time to celebrate the United Nations (UN) Literacy Decade of 2003 to 2012, Kumaresan said, and an opportune moment to convene this roundtable on health literacy. Health literacy is the cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, to understand, and to use information in ways that promote and maintain good health. Health literacy implies achievement of a level of knowledge, personal skills, and confidence to take action to improve personal and community health by changing personal lifestyles and living conditions, Kumaresan said.

Kumaresan said that health education aims to influence individual lifestyle decisions and raise awareness of the determinants of health. This is achieved through methods that go beyond information diffusion; it entails interaction, participation, and critical analysis. Health education leads to health literacy, he said, which then empowers individuals, families, and the community. Health literacy goes beyond a narrow concept of health education and individual behavior-oriented communications to address social, environmental, and political issues.

Health literacy is a tool for empowering people to take control of their

health by helping them properly use information, leading to personal and social benefit and thereby enabling community action and the building of social capital, Kumaresan said. It is a means to social and human development. Because it improves people’s access to health information and their capacity to use it, health literacy is critical to empowerment.

Major challenges exist, however. Worldwide the level of health literacy is low. Kumaresan noted that people with low levels of health literacy are more likely to

- have a low level of information and communication technology literacy and less access to the Internet and online health information,

- not be able to evaluate the quality of information from different sources, and

- have lower use of preventive services and higher use of treatment services resulting in higher health care costs.

Although there is a plethora of health information on the Internet, there is a lack of evidence-based information that is easily available to the general public. There is no standard quality check, and it is difficult for consumers to understand and evaluate the accuracy of the information they do have, Kumaresan said. Furthermore, the level of health literacy in many developing countries is unknown. Cultural issues and language barriers also exist.

Kumaresan described several strategies for improving health literacy. First, community action for health should be a key component of health literacy. And, in order for that to be helpful, Kumaresan added, one needs a well-functioning, rights-based, patient-centered health care system. Finally, there must be multisector collaboration at the national, regional, and international levels to provide all people with access and to overcome inequities.

Inequalities in health are a major problem, Kumaresan noted. For example, in New Zealand the gap between non-Maori and Maori life expectancies was 16 years for males and 14 years for females in 1951. With strong government action that gap decreased to about 7 years for both in 2006. But this decrease required major action by the government and strong leadership from the Ministry of Health, Kumaresan said. Strategies and actions included providing universal access to health care services, appropriate education materials, community empowerment programs, and educational programs to help increase the literacy levels of consumers. Education needs to be provided not only by the clinics and hospitals but also by other institutions that can increase public health literacy rates such as schools, colleges, workplaces, and libraries.

Also important is the use of innovative and appropriate information and communication technologies to bridge the health literacy gap and pass

on information using traditional media, mobile devices, and the Internet, Kumaresan said. The term mobile health is used to describe the use of mobile and wireless devices to improve health outcomes, health care services, and health services. The mobile health tobacco cessation project, a program of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Telecommunications Union, is an example of success with new technologies. The project used mobile phones to send messages aimed at raising awareness of risk factors, screening, and citizen reporting. The Short Message Service (SMS)-based cessation programs are low-cost, personalized, and interactive, and they provide information on medication and support tools, as well as encouragement, Kumaresan said. Successful programs have been implemented in the United Kingdom, the United States, and New Zealand.

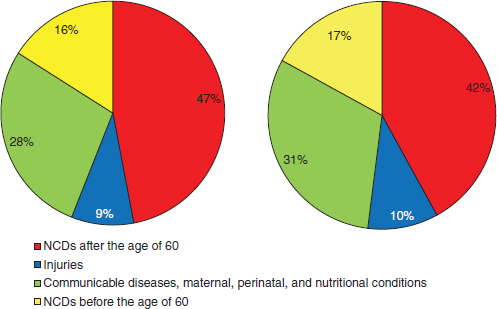

Kumaresan said that noncommunicable diseases are responsible for the highest proportion of deaths globally (see Figure 3-1). This is also a critical issue for low- and middle-income countries. Hence, for only the second time in the history of the United Nations, a health issue was discussed at the high-level meeting in September 2011, attended by heads of state. World leaders adopted a political declaration on prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) that requests the UN Secretary-General, in cooperation with the Director-General of the WHO, to prepare a report on strengthening multisectoral preventive action and to report on progress made in combating NCDs (UN General Assembly, 2011a).

One approach to addressing NCDs is through the use of mobile health, which has been used to train health workers and trainee nurses about prevention of noncommunicable disease risk factors. Text messages, Kumaresan said, can be used to improve diabetes management compliance and encourage the use of condoms. Mobile technology can also use sensors to track and map use of inhalers by asthmatics. Mobile health technologies are important because their reach in developing countries is so much greater than other technology or health infrastructures. He said that in developing countries 11 million people have access to hospital beds and 305 million people have access to computers, but 2.2 billion people use mobile phones, and 40 percent of those users are in rural areas. The global coverage for mobile phones is 7.4 billion today and is projected to be 10 billion by 2017 (BBC, 2012).

Use of mobile health technologies overcomes structural barriers to health by allowing for more personal forms of communication and community-based educational outreach, Kumaresan said. One example is the CommCare program in the state of Bihar in India. This program uses a mobile phone application as a tool for “counseling adolescent girls and women on menstrual hygiene, sexually transmitted diseases and family planning methods” (Treatman et al., 2012). This is a rural develop-

FIGURE 3-1 The rapidly increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases in the developing world.

NOTE: NCDs = noncommunicable diseases.

SOURCE: WHO, 2011.

ment program supported by the Ministry of Health, and it is helping to empower young women.

Examples of health literacy in action can be found in many parts of the world. In the Philippines, for example, there is a national plan for a campaign to promote breastfeeding and infant nutrition. This program resulted in not only an increase in breastfeeding but also a decrease in the infant mortality rate, Kumaresan said. Another example is a malaria program in eight countries in Central America. The program consists of an environmental campaign focused on community cleaning of neighborhoods without the use of DDT pesticide. People were encouraged to cover water storage containers and drain standing water. They organized community cleanings in streets, forest areas, and swamps. In 2 years, there was a reduction in vector density and a 63 percent reduction in malaria cases, Kumaresan said.

The WHO partners with UN agencies to promote health literacy work. In February 2012, the WHO, in collaboration with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), launched the National eHealth Strategy Toolkit1 to help individual governments develop an e-health strategy,

____________________

1 The toolkit can be found at http://www.itu.int/pub/D-STR-E_HEALTH.05-2012 (accessed November 15, 2012).

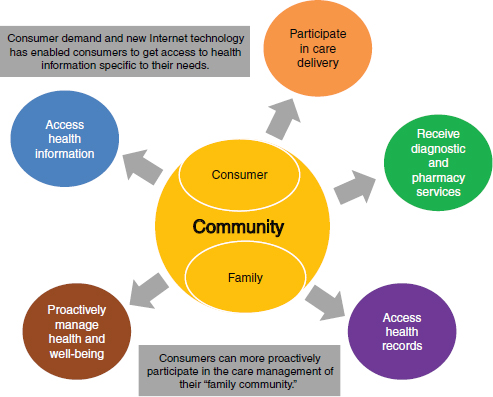

action plan, and monitoring framework at the national level. An e-health infrastructure (see Figure 3-2) can help manage health and well-being by monitoring and managing medications. It can access records—either personal or medical records—and it can have automated dispensing of medication. There can also be interaction with care providers and remote monitoring.

WHO regional offices are closely involved in building health literacy, mobile health, and e-health efforts. For example, according to Kumaresan, the European region has initiated various programs that are empowerment focused. First is the NCDs prevention program that supplies information and tools to prevent and manage such diseases. A second program is focused on mental health, and the third is focused on patients’ rights and safety around the theme of blood transfusion and hospital infections.

Kumaresan concluded by saying that the way information is provided to people should increase understanding, not baffle the recipient.

FIGURE 3-2 E-health architecture model.

SOURCE: Kumaresan, 2012.

POLICIES AND PROGRAMS PROMOTING HEALTH LITERACY GLOBALLY

Scott C. Ratzan, M.D., M.P.A.

Vice President, Global Health

Johnson & Johnson

Ratzan begin by quoting the preamble of the constitution of the WHO that states, “Informed opinion and active cooperation on the part of the public are of the utmost importance in the improvement of health of the people” (WHO, 2006). Much of health literacy is focused on the public good, that is, on helping to create the conditions under which people can be informed and actively participate in their health management. It will take time to marshal the necessary forces to achieve health literacy for the world’s population, Ratzan said.

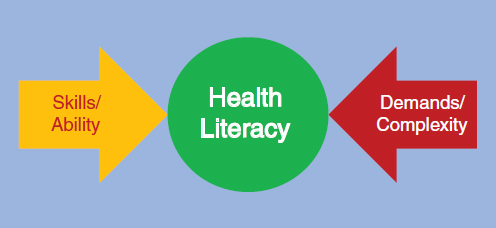

“Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (Ratzan and Parker, 2000). This definition can encompass mobile health information and e-health technologies. It also addresses health services, which is important because much of what needs to be addressed is how health care is delivered. The framework for health literacy involves both individual skills and abilities as well as system complexities (see Figure 3-3).

Ratzan said this framework fits well with Kumaresan’s discussion of health promotion and quality. In the figure, on the left in yellow, is what many people think of as health education for individuals. On the right

FIGURE 3-3 Health literacy framework.

SOURCE: Parker, 2009.

in red is a component of the health care quality discussion—how can the demands and complexities of the system be simplified? And in the middle is health literacy.

Fortunately, there are a number of discussions on health literacy going on around the world. In October 2008, Ratzan said he participated in an European Union (EU) high-level pharmaceutical forum. Emerging from that forum was an EU declaration that stresses the need to enhance health literacy as a policy at EU and member-state levels. He recommends that future EU policy on information to patients on diseases and treatments should move toward new approaches in a coordinated manner and build on a dialogue with stakeholders, promoting health literacy and health information in the broadest sense (European Communities, 2008).

At a July 2009 meeting of the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in Beijing, the ECOSOC issued a ministerial declaration stating, “We stress that health literacy is an important factor in ensuring significant health outcomes and in this regard, call for the development of appropriate action plans to promote health literacy.”2 Several months later, Ratzan said, the Chinese health minister, during a speech in Geneva, Switzerland, said that health literacy is an important factor in ensuring positive health outcomes and called for the development of appropriate action plans to promote health literacy.

In September 2011, a political declaration of the high-level meeting of the UN General Assembly on the prevention and control of NCDs was issued. One of the recommendations reads,

Develop, strengthen and implement as appropriate, multisectoral public policies and action plans to promote health education and health literacy, including through evidence-based education and information strategies and programmes in and out of schools, and through public awareness campaigns. (UN General Assembly, 2011b)

It was specifically decided and widely supported to view health literacy as different from health education and to state that health literacy programs occur in more places than just schools. The focus now is how to implement this NCD action plan.

Health literacy is also a priority in the United States. In May 2010, the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy was released. It has seven goals and during the release of the plan Secretary Kathleen Sebelius of the Department of Health and Human Services stated, “Health literacy is needed to make health reform a reality. Without health information that

____________________

2 See http://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/julyhls/pdf09/ministerial_declaration-2009.pdf (accessed November 16, 2012).

makes sense to them, people can’t access cost-effective, safe, and high-quality health services” (HHS, 2010).

Twenty-one states have ongoing health literacy activities,3 and more are developing programs at the city, county, state, and regional levels, Ratzan said. Health communication and health literacy is also integrated into health professional training. For example, the University of Minnesota School of Public Health has a course that addresses health literacy and its relationship to health disparities. Evolving competencies for 21st-century medical training provide an opportunity for increasing knowledge about health literacy, Ratzan said. Use of health checklists or scorecards and mobile health applications in the private sector are other avenues to improve health literacy.

Ratzan said that for the past 2.5 years he has been working with the WHO Innovation Working Group (IWG) Task Force that is focused on creating innovative ways to improve the delivery of health care. One approach related to health literacy is the use of checklists and scorecards. Atul Gawande made groundbreaking strides in the idea of the checklist with his book The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. A New York Times article by Ezekiel Emanuel (2012), cited a 2006 study (Pronovost et al., 2006)4 that found a five-item checklist could be used to reduce infection rates from intravenous catheters to zero, thereby saving $45,000 per patient and avoiding 28,000 deaths in intensive care units. An editorial in the Lancet (Editorial, 2012) stated: “new frugal technologies do not have to be sophisticated gadgets, but can be as simple as a checklist. A 29-item Safe Childbirth Checklist has been developed and successfully piloted in India, with a draft version available by the end of 2012.” Examples of checklists for improving health outcomes can be found in Table 3-1.

Although the examples provided are checklists for improving the quality of provider activity, other areas are ripe for health literacy checklists, Ratzan said, including a checklist for the last 30 days of pregnancy. A yet-to-be released report of the IWG, edited by Ratzan and Jonathan Spector, highlights the potential of checklists for improving health literacy, including the following:

- Checklists are a low-cost innovation with an increasingly large evidence base to address management of complex or neglected tasks.

____________________

3 See http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/StateData/index.html (accessed November 26, 2012).

4 The study title is An Intervention to Decrease Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in the ICU.

- Effective checklist programs bundle vital elements of existing guidelines into a simple, user-friendly format comprised of actionable items.

- Prior health-related checklist programs have been shown to reduce complications and save lives (e.g., surgery, childbirth, and other fields).

Ratzan said that multiple stakeholders continue to advance health literacy at many levels. There are unparalleled scaling opportunities with online and mobile communication technologies that provide new promise and opportunities for advancing health literacy. Future options may include checklist tools that provide easily accessible, understandable, and actionable health information to patients and consumers of varying lev-

TABLE 3-1 Examples of Health Checklists

| Initiative | Description | Current Stage |

| Central Line ICU Checklist | Simple five-point checklist to ensure safe insertion of central-venous catheters; proven to significantly reduce central line infections | Global rollout |

| WHO Surgical Safety Checklist (2007–) | Universally applicable tool to systematically ensure that all conditions are optimum for patient safety during surgery; proven to reduce severe morbidity and mortality | Global rollout; in use in >4,000 hospitals and national policy in several countries |

| WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist Program (2008–) | Checklist-based program for reducing childbirth-related mortality in institutional births in lower-income settings; shown to significantly improve adherence to essential clinical practices | Development and pilot testing successfully completed; currently in large-scale rollout and evaluation phase |

| mCheck “7-day” Tool (2010–) | WHO Patient Safety Programme project aimed at empowering women with a simple checklist complemented by a mobile phone component | Development completed; currently in evaluation phase (Kamataka State, India) |

| SOURCE: Ratzan, 2012. | ||

els of economic status and health literacy. Checklists and scorecards are, Ratzan said, becoming widely acceptable tools that can advance health literacy and make improvements in other areas such as NCDs.

The book Just Six Numbers by Martin Rees (2000) explored the idea that six factors are necessary to shape the universe, and if one of these numbers were not in place, there would be no universe. This concept triggered Ratzan to think about whether something like this could be developed for health, that is, could there be a simple, digitized scorecard of six or more factors necessary for health? Ratzan (2000) proposed a scorecard of the following six factors:

- Blood pressure/heart rate

- Body mass index

- Cholesterol levels

- Immunizations

- Appropriate preventive measures (e.g., smoking cessation, sigmoidoscopy, mammograms)

- Self-reported health status

At an Institute of Medicine (IOM) Roundtable on Health Literacy workshop on promoting health literacy to encourage prevention and wellness (September 2009), Ratzan presented a paper that developed the theme of using scorecards to improve health and health literacy. Numerous organizations and individuals have pursued the development of scorecards for health, Ratzan said. For example, the World Health Professions Alliance is using an adapted version of the scorecard presented at the IOM meeting.

As the evolution in scorecards continues, Ratzan said, people are beginning to look at how they can be used online and with mobile technology. Perhaps there could be a digital health score to keep track of one’s health, similar to one’s credit score, Ratzan said (see Figure 3-4). The scorecard could educate people about simple goal ranges enabling them to see how they rate and how they can improve. It could also provide a range of medical and health indicators and behaviors, thereby helping people understand how lifestyle choices and NCDs are connected. Such a scorecard could, Ratzan said, motivate action by accurately portraying risk and preventability. Finally, the scorecard would provide the ability to track ratings over time to show trends and incentivize improvement.

Another mobile application that helps people make appropriate deci-

sions is Text4baby.5 This is a U.S.-based text service for women who signed up to receive stage-based messages during pregnancy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2012) reports that 96 percent of the 281,000 enrollees said they would recommend the service to a friend. Preliminary data indicate that this is an effective approach for increasing knowledge and changing behavior, Ratzan said. The Mobile Alliance for Maternal Action (MAMA) is a similar program run on a global level. It was found that in Bangladesh people needed to hear the message rather than just read it, so it is now sent in the local language, Ratzan said.

All of these different approaches are helping people make better health decisions, Ratzan said. For the future, checklists and scorecards can have major global impacts for patients and consumers, Ratzan said, including reduction of chronic, NCDs, maternal and child mortality, and infectious diseases. New technologies provide better access and use of information, contributing to expanded health literacy globally and helping to relieve the burden on already strained health workers, Ratzan said. Mobile health or mobile health communication holds great promise as efforts at providing information are scaled up.

Ratzan concluded by saying there are many opportunities to share innovations and programs aimed at health literacy and improving health.

UNITED STATES: HEALTH LITERACY AND RECENT FEDERAL INITIATIVES

Cynthia Baur, Ph.D.

Senior Advisor for Health Literacy

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Baur said that it is time to commit to measurable organizational change in health literacy. A very large and robust infrastructure has been put in place to support that change, she said, and there is a large network of individuals throughout the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) committed to making sure that health literacy becomes part of all types of health action. The United States has taken the approach of putting many key pieces in place, and the challenge now is to move from the abstract to the concrete, to commit to measurable organizational

____________________

5 “Text4baby is a free cell phone text messaging service for pregnant women and new moms. Text messages are sent three times a week with information on how to have a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby. The text messages are timed to the pregnant woman’s due date or the baby’s date of birth” (http://www.cdc.gov/women/text4baby [accessed November 26, 2012]).

change in a concrete way. Three key questions will be answered in this presentation, Baur said. They are

- What are the key developments in health literacy in the United States?

- How has the HHS contributed to health literacy improvement?

- Where can we go from here?

Despite the fact that there is a great deal of information, communication, and education, there is still a gap between the public and health professionals. The professional community has not changed its practices enough to communicate effectively with the public, Baur said. And in some places, for some populations, under some circumstances, this gap can be quite large. Health literacy research and evaluation brings knowledge about how to communicate, how to educate, and how to obtain the maximum effectiveness from these efforts, Baur said. We do not need more communication, we need different kinds of communication and different kinds of education that pay attention to the health literacy insights that are available in the literature. One of the most obvious gaps is the education sector’s lack of support for health literacy activities, Baur said.

There are several key developments in health literacy in the United States. Many of the activities are being conducted by private-sector organizations. But the federal government is also active in health literacy. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, while not a health literacy law, does contain important provisions for addressing health literacy. The Plain Writing Act of 2010 is another development. That law directs federal agencies to use plain language in all public communications. Although the law is not health specific, it can be used to address health literacy in public health information. There is also a law related to the use of health information technology that, while not health literacy specific, is fundamentally changing the way that technology is being used to deliver health care in the United States, Baur said. These laws have laid a foundation for health literacy work in the United States.

Baur said that since 2004 the National Institutes for Health have funded $95 million in research under the Health Literacy Program Announcement. While this is a fairly large amount, it does not reflect the total support for health literacy research because other research has been funded through other mechanisms and agencies. For example, the CDC uses contracts to support health literacy work and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) uses cooperative agreements.

The Journal of Health Communication has supported a number of special issues related to health literacy, and in January 2012 Health Affairs

published an article by Koh6 and colleagues on policy initiatives and health literacy. It was, Baur said, the second-most-read article in Health Affairs between January and June 2012. A number of bibliographies have also been published. The growing literature that people can draw on and build on for implementation and research is, Baur said, part of the infrastructure to support health literacy work.

Health Literacy Online, provided by the HHS Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (available at http://www.health.gov/health-literacyonline), is an example of some of the research-based guidance that is available to organizations. This is a practical, hands-on guide that helps people apply health literacy principles to the design of health websites. Other aids include the toolkit on clear communication strategies developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and plain language manuals. And for Healthy People 2020 (U.S. national objectives for health), health literacy objectives were expanded to include health information technology objectives as well as being included under some of the more traditional health topics, Baur said.

There are also a number of state-based activities in health literacy. On the CDC Health Literacy website,7 there is a map that highlights the states with verifiable health literacy coalitions or collaborations. More states that will be added to the map soon because they are having inaugural health literacy conferences in 2013. States are working to build their own infrastructures at the state level to support a more collaborative approach to health literacy improvement, Baur said.

Many publicly available tools can be used to assess the quality of health care services, and there is a health literacy module to assess providers’ use of different health literacy and health communication strategies, Baur said. There are also a number of robust health information services. Healthcare.gov, sponsored by CMS, provides information about access to health insurance. MedlinePlus, sponsored by the National Library of Medicine, and healthfinder.gov, sponsored by the HHS, provide health information built on plain language principles in order to make information more accessible to all segments of the public, Baur said.

All these activities support the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy, a comprehensive framework organizations can use to identify priorities, strategies, and activities for health literacy. There are seven goals within the National Action Plan (NAP). They focus on

____________________

6 Dr. Howard Koh is U.S. Assistant Secretary for Health.

7 Health literacy: Accurate, accessible, and actionable health information for all (http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy [accessed November 28, 2012]).

- Creating and disseminating information,

- Providing health care services,

- Educating people,

- Delivering services through community-based organizations and nonprofit organizations,

- Working together across organizations and across sectors,

- Conducting research and evaluation, and

- Telling others about the research and evaluations completed.

The NAP has put health literacy on the national agenda, Baur said. It allows local organizations to link their work to the national agenda and confirms the importance of health literacy as a policy topic. The NAP also provides talking points, benchmarks, project ideas, and conference themes. It provides the “glue” for local coalitions, Baur said. Organizations that might not think they have much in common can use the NAP as a framework for identifying common interests in health literacy.

Baur provided quotes from some organizations in the field that use the NAP. Beth Rueland, from Health Literacy San Diego, said,

We use the NAP as a benchmark to align with national best practices and recommendations. In addition, the NAP helps health and literacy efforts across the nation compare and share best practices, as well as understand how they can align their efforts to take full advantage of recent policy and legislation changes.

Dr. Suad Ghaddar of the South Texas Border Health Disparities Center said,

The NAP has helped identify key strategies that we feel the Center can be involved in at the community level. We have identified potential partners and initiated outreach activities to improve health literacy.

Where do we go from here? Baur asked. As stated earlier, the key message is about organizational change. How can we promote organizational change to incorporate health literacy in our everyday practices? Organizational change must happen at the individual organization level but also in the broader sectors of industry, government, education, and nonprofit organizations. The NAP is relevant here because it talks about groups of organizations as sectors, and change must occur within these sectors, Baur said.

Baur said that organizational change requires us to examine research for insights in practical applications, create and implement easily usable products, and track and report progress in changing our organizations. There is a need to document what health-literate organizations are doing differently from other health organizations. There is a need to document impact on policy-relevant outcomes, Baur concluded.

Jennifer Cabe, M.A.

Executive Director

Canyon Ranch Institute

and

Suzanne Thompson, M.S.

Vice President, Research & Development

The Clorox Company

Thompson said that Clorox and Canyon Ranch Institute (CRI), in a public–private partnership, are jointly working on a program to improve hygiene in very poor communities in Peru by combining health literacy, microbiology, and public health science. Clorox was founded in 1913, making Clorox liquid bleach. Today the company has a broad range of products, with 8,400 employees and sales of $5.5 billion. Clorox is headquartered in Oakland, California; it has 24 plants in the United States and manufactures products in 25 countries. It markets products in 100 countries and has 6 facilities for research and development.

Cabe said that CRI is small when compared to Clorox. It was founded in 2002 and is a 501(c)3 nonprofit public charity with a 7-member board, 8 employees, 40 volunteers, and more than 90 funding sources. It seeks to deliver the best practices of the institute and its partners to health-disparate communities; to inform health policies in all sectors; and to partner with universities, grassroots organizations, corporations, and foundations. Cabe said that CRI has a global reach because of collaborations with its partners. Through an integrative approach to advancing health literacy, CRI is able to address challenging problems in public health, working with partners and looking beyond causes of problems to the causes of the causes.

An individual who sits on both the Clorox and CRI boards suggested the two organizations should be working togther. While Clorox is a for-profit company and CRI is a nonprofit public charity, their fundamental guiding principles, missions, visions, and values are complementary. Both organizations are interested in improving lives, both value working in partnership with others, and both are principled in all approaches, Cabe said.

Improving health is a priority for both companies, Thompson said. Clorox has a disinfecting heritage and focus on improving health through hygiene, both in water disinfection and in hard-surface disinfection. The company also has a number of programs to educate people on how to improve their own and their families’ health through hygiene and disinfecting products. CRI, with its strong health literacy focus and great skill at educating people, was a great fit for Clorox, Thompson said. With these

backgrounds, collaboration on the program in Peru was a perfect place to start a partnership, Thompson said.

There are some major factors necessary for a successful partnership. First is to make clear each organization’s role and responsibilities. Second, ongoing communication and collaboration is needed. The working team had regular conference calls and occasional face-to-face meetings. The two project leaders talked regularly to make sure they were giving consistent direction and messages.

Most importantly, Thompson said, they leveraged the strengths of both organizations. Clorox provided the funding, public health experience, and business experience in Peru. It also identified the University of Arizona as a partner for conducting the microbiology research. CRI brought overall program leadership and a strong expertise in the social sciences and health literacy. It identified Boston University’s College of Fine Arts as an arts partner. It also identified Peruvian arts and social science partners.

The program is called Arts for Behavior Change. It is a pilot program that uses the arts to help people understand what needs to be done to improve personal and household hygiene behaviors as well as how to use different disinfecting products. Importantly, this is an unbranded program, so it did not promote Clorox products, Thompson said.

Cabe said there were several measurable key outcomes. One of the areas in which the program greatly exceeded expectations was attendance by community members and participation in the 12 performances. There was increased knowledge and understanding about hygiene, and there were actual improved personal and household hygiene behaviors in the areas targeted by the intervention. There was also reduced microbiological burden in areas targeted by the intervention.

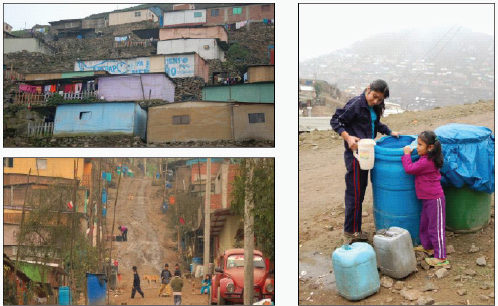

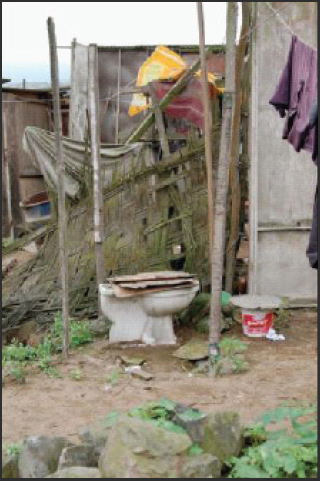

The decision was made to work in shantytowns in Peru. It is important to note, Cabe said, that the term shantytown is not a pejorative—it is the term Peruvians themselves use to describe the communities. In November 2010, a team from CRI, Boston University, and The Clorox Company conducted site visits at numerous shantytowns around Lima, and two were chosen for the program (see Figure 3-5). There is tremendous need in these communities. There is no plumbing. If one can afford to purchase water it is delivered through blue barrels placed alongside the road. The barrels are not clean and the buckets used to obtain the water are not clean either. So the water comes dirty and that is how it is used.

All work in the Peruvian shantytowns was conducted in the Spanish dialect spoken there, Cabe said. A formative assessment was conducted in the two shantytowns to inform program design, including the stories and characters that would be used. In-depth interviews were conducted with

FIGURE 3-5 Program site in shantytowns of Lima, Peru.

SOURCE: Cabe and Thompson, 2012.

250 households before the start of the performances and with 249 households after the final performance. Observations were also conducted with 50 households before the start of the performances and after the final performance. Following each performance 20 individual interviews were conducted immediately. The performances were structured as a telenovela.8 Microbiological studies were conducted in 30 households both before and after the performances. There was intensive and diverse community engagement throughout, Cabe said.

One of the most interesting aspects of this arts program that used health literacy to improve household hygiene was the opportunity to work with a community of actors, singers, puppeteers, and dancers, Cabe said. During a 2-week workshop in Lima, these individuals were trained in health literacy principles and the science of personal and household hygiene. Microbiologists from Clorox and the University of Arizona also taught everyone some basics of microbiology.

Also during this 2-week period, the first four episodes of the telenovela were outlined. There was, however, constant change in all of the episodes

____________________

8 “The telenovela is a form of melodramatic serialized fiction produced and aired in most Latin American countries” (http://www.museum.tv/eotvsection.php?entrycode=telenovela [accessed November 29, 2012]).

because of the interaction of the community. The key thing to emphasize when talking about this kind of partnership, Cabe said, is the importance of engaging and honoring the existing leadership structures in the communities. This was critical, she said.

The play was called Siempre, which translates in English to Always, as in “always sick.” Two families made up the characters portrayed on the stage—the Maranas and the Buendias. Maranas means disorganized or messy. Buendias means the good days. The basic plot is that the father is missing, the mother says he is dead, but the father is seen with a younger woman. Both families have ongoing health problems related to poor hygiene. The onstage presence of the “Joker”—a physician and public health practitioner—kept the performance grounded in science.

Throughout all 12 performances, the community was extremely engaged, Cabe said, coming up on stage, asking questions, even replacing the actors up on the stage when they wanted to say, “Here’s how I think something really should go.” For example, around episode seven, one of the beloved characters—a little girl—died. The community did not like that. So the Joker (the public health physician) said, “All right. You know enough now. Maybe we could have prevented the death of this child. How would that occur?” And people in the audience stood up and explained how the death could have been avoided. So the little girl was brought back into the performance, which meant a lot of rewriting for the writing team, but that was fine because the community was really engaged.

In terms of outcomes, overall, there was strong diffusion of information throughout the community and behavior changes based on the performances:

- 97.5 percent of respondents were aware of the performances.

- 69.6 percent of respondents attended the performances.

- 91.3 percent of respondents said they learned something from the performances.

- 77.2 percent of respondents said the performances were important or very important to their lives.

- 54.4 percent of respondents said that there have been changes in household hygiene behaviors during the past 3 months. Of those, the majority said it was because of the performances (means of 3.15 on a 4-point scale).

The microbiological outcomes were more mixed, Thompson said. The overall microbiological load was very high both before and after the performances. This is largely due to the high poverty level of the community and the openness of the water and waste. For example, Figure 3-6 shows a

FIGURE 3-6 A community toilet.

SOURCE: Cabe and Thompson, 2012.

community toilet. One thing learned is that the microbiology team needed to be much more closely linked to the performance messages to make sure the testing before and after was related to the areas the performances were highlighting. Despite these challenges, there was great improvement in food preparation areas, with a 34.4 percent overall decrease in positive results when testing for E. coli and listeria. The change correlates with the performance messages, which featured why and how to clean food preparation areas, Thompson said.

The Arts for Behavior Change pilot project demonstrated the effectiveness of community engagement and using performance arts to advance health literacy and improve health-related behaviors, Thompson said. The

project also demonstrated the ability of a public–private partnership to achieve meaningful community health benefits. Finally, Thompson said, there is great opportunity to improve public health by replicating the program in different communities and cultures.

In terms of their next steps, Clorox and the CRI are identifying and implementing the lessons learned from the pilot program in order to improve overall outcomes of future programs. They are also communicating the processes and findings of this pilot through publications and presentations. Finally, they hope to expand the program by identifying additional funding sources and partners, Thompson said.

One audience member asked Baur what the grade level is for producing plain language and understandable materials. Baur responded that, in general, grade levels are not used as targets because communication is a far more complex process than a grade level can represent.

A different audience member asked Ratzan whether there were any data about the effectiveness of mobile health text messages. Ratzan responded that an article in JAMA on text messaging for vaccination among adolescents showed uptake. Kumaresan said an article in the Lancet showed a doubling in smoking quit rates within a period of 6 months for the 5,000 participants in mobile health messaging as compared to the control group. Also, Kumaresan said, mobile health is a wonderful way to conduct outreach. For example, in 2010, for the World Health Day on urban health, the only way to reach people in Somalia was with text messages (1 million were sent to Somalia residents) sent by the water and telephone companies. That was an amazing public–private partnership, he said.

Research in this area is important, Ratzan said. The WHO IWG Task Force has research members who are interested in outcomes of use of mobile health messaging. Kumaresan added that measures are needed in order to better understand the effect of mobile health messaging.

Will Ross, a Roundtable member, said he appreciated Kumaresan’s comments about using a rights-based approach to coordinate health literacy interventions globally. He asked if it were possible to codify what needs to be done yet still use such an approach and make sure programs are conducted in a manner that allows countries to determine important outcomes. Kumaresan responded that one of the best examples is a program in tobacco control.9 The program was begun in 2005 and within

____________________

9 “The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) is the pre-eminent global tobacco control instrument, containing legally binding obligations for its Parties, set-

a period of 6 years, 175 countries signed on to conduct it. Application, however, is different. Every year, WHO monitors how much of the framework and the articles have been implemented. It takes a long time. In Australia, for example, it took 3 or 4 years of effort to get plain packaging implemented. But other countries will follow suit. Mechanisms are needed, Kumaresan said, to ensure that countries can adapt to their own circumstances yet still be held accountable. Successful models are needed to ensure that UN resolutions and WHO resolutions can be implemented. This takes a long time.

Allison MacEachron from the business council for the United Nation said that the panel provided a number of great examples of collaboration between the public and private sectors. She asked, “Where are the gaps and the biggest opportunities for the private sector to collaborate with the UN and UN agencies in ways to help meet the goals of health literacy?” Ratzan responded that the IWG is a good place to start. This group is a network of leading stakeholders from government and both the for-profit and the nonprofit sector, including health foundations, academic institutions, and businesses. One piece that is missing is the media. The media is not just a conduit, but an ongoing purveyor of health information, Ratzan said. Another possible resource is the CTIA, a cellular telephone group that is working to scale up some mobile health pieces. Although public–private partnerships are growing, Ratzan said, not all governments are open to working with the private sector and not all private-sector companies are the same in terms of being ethically based and trustworthy. There needs to be a good fit among partners in a public–private partnership, Ratzan said.

Baur said that because of competition and different business models the private-sector organizations may not be as open as other organizations in terms of sharing information. However, one possible outcome of a public–private partnership might be increased transparency across all kinds of activities and projects.

Cabe said the real key is to maintain a balance between pushing commercial interests and doing the right thing. Is the private-sector company involved just to make money or because it has a goal of improving

____________________________________________________________

ting the foundation for reducing both demand for and supply of tobacco products and providing a comprehensive direction for tobacco control policy at all levels. To assist countries to implement effective strategies for selected demand reduction related articles of the WHO FCTC, WHO introduced a package of measures under the acronym of MPOWER. WHO recently reported the progress Member States are making against the MPOWER measures in the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2011” (http://www.who.int/gho/tobacco/en/index.html [accessed November 29, 2012]).

people’s lives? With companies that have a strong foundation in pursuing high-integrity activities, Cabe said, partnership activities can succeed.

Isham asked whether it could be assumed that the nature of public–private partnerships is the same for different countries around the world. Ratzan responded that it is not the same. There are different models for how companies approach a partnership, and each partnership needs to be culturally sensitive and address local needs and resources.

Winston Wong, a Roundtable member, asked about scalability of projects. Ultimately health literacy efforts get the most traction at the local level. What needs to be considered in, for example, performance metrics, infrastructure, and resource deployment to move a program from a local level to one that has a global impact? Cabe responded that this is a very important question that CRI and Clorox have been asking about the Arts for Behavior Change program that was piloted in Peru. Of major importance in that program was community interaction with the social scientists and the microbiological researchers in order to empower the community. Greater empowerment drives improved outcomes, Cabe said. Can technology—in this case, radio, television, and videos—be used to scale up efforts? How can the stories be told in a health literate, engaging manner that is going to reach a lot more people than were reached in the two shantytowns in Peru?, she asked.

Baur said she thinks about scalability differently. There is scalability in terms of the number of people touched by a project or intervention. Then there is scalability in the context of large organizations. How does one get an entire organization to move? One can go team by team, branch by branch, and division by division. But that is very slow, she said. What other options are there? Baur pointed out that both the CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration could use funding mechanisms to scale up health literacy efforts. If one inserts health literacy, plain language, cultural competence, and limited English proficiency into the funding announcement template, one has immediately affected every single program that uses the template to request proposals, she said.

Ratzan said that what Baur has alluded to is the idea of moving from local to social change. That is what is needed for health literacy, he said. He asked, “How can we integrate new tools such as scorecards and checklists and mobile health messaging that could foster change on a larger scale?” Kumaresan said there are three factors required to scale up an effort. The first is to show the effectiveness of an initiative. The second is to get the community to understand the value of the initiative. The third is to have a national policy that fosters the effort.

Kumaresan described a project in Ethiopia in which he was involved.

Partners in the Trachoma10 project included the Carter Center and Pfizer. Water, sanitation, and hygiene were important elements of the project and getting people to build latrines was a high priority. The Carter Center target was the building of 10,000 latrines in one particular community. In 1 year there were 92,000 latrines built because the members of the community saw their value. The women of the community had decided that there needed to be one toilet per household. They saw that children did not have trachoma disease or diarrhea. When President Carter visited the community and asked what they needed, the response was: “Our children are now healthy. Will you please build us a school so our children can go to school?” It is interesting to note that the Ethiopian government now has a policy of one latrine per household.

Len Epstein, a Roundtable member, asked how health literacy can more effectively integrate culturally and linguistically appropriate health and health care perspectives. Baur responded that literacy is a culturally specific activity. When one talks about literacy, one must speak in terms of a particular context. In the U.S. context, there is the issue of limited English proficiency and the need to provide interpretation and translation. But there is a move to go from this traditional approach to a broader notion of understanding. It is not just interpretation and translation; it is ensuring that people have a better understanding of what the encounter is about.

One participant who identified herself as coming from Indonesia and working with the Indonesian delegation to the UN General Assembly shared information about what is going on in Indonesia. The country is, she said, building an integrated health intervention program at seven pilot areas to reorient the primary care system. The reorientation aims for community empowerment and health literacy. Many sectors work together—private, government, and nongovernmental organizations, including Nokia. Indonesia has a population of 240 million people. About 80 percent of those people have mobile phones. Nokia built an application (app) that will be given to women. Questions will be asked and, based on the responses, the app will direct the user to the appropriate information.

Diane Levin-Zamir said that public–private partnerships in Israel are required to be open to any private-sector company that would like to be a partner. Those who express an interest are evaluated based on specific criteria that include health promotion. In this way the public sector is able to address the ethical questions that would arise if it were choosing one

____________________

10 “Trachoma is the result of infection of the eye with Chlamydia trachomatis. Infection spreads from person to person, and is frequently passed from child to child and from child to mother, especially where there are shortages of water, numerous flies, and crowded living conditions” (http://www.who.int/topics/trachoma/en [accessed November 29, 2012]).

company or one private investor. Levin-Zamir asked Cabe to what extent the private-sector partners for CRI are required to have a health promotion or health literacy agenda within their companies.

Cabe responded that she was uncertain how well a system that required allowing any and all private companies to participate would work in the United States given the very competitive nature of business. There are many companies that probably would worry too much about revealing their secrets. There are also antitrust issues that might be a challenge. Also, Cabe said, the cultural fit of organizations is very important to the success of a program. Her organization partners only with organizations that have a strong belief in promoting health and wellness, organizations like Clorox, the Red Cross, and others involved in disaster relief. Ratzan added that transparency is also key to successful partnering.

Isham said this discussion highlights a key issue when attempting to establish partnerships: the need to maintain a balance between respecting a company’s right to privacy and the need for cooperation. That balance must be negotiated in each partnership arrangement, he said.

Sabrina Kurtz-Rossi, a principal in a woman-owned small business specializing in health education, literacy, and evaluation, said she is interested in supporting professional and organizational development in the field of health literacy. Many people have come to identify themselves as health literacy professionals even though they come from many different professions and different kinds of organizations. How can new technologies be used to share information and tools and to build collaboration among these individuals? How can best practices and basic competencies be shared? There seems to be a need for a mechanism that would allow this, she said.

Baur said that when the CDC launched its health literacy website (CDC.gov/healthliteracy) it included links to known international activities, but the traffic for this information was nonexistent. No one was using the information. People were using U.S. state-based data. So the international links were moved to a second-level page.

In terms of information sharing, Baur said, that is one thing the website was intended to do; however, not many people have responded to the postings. The blog is supposed to facilitate sharing, but it will not work if those reading the blog do not post comments. There is also a health literacy mailbox but the kind of feedback received is generally about a problem with an online system. There is a huge opportunity, Baur said, but it has not been taken advantage of.

Ruth Parker, a Roundtable member, said that the IOM Roundtable on Health Literacy commissioned a paper on international health literacy activities which Andrew Pleasant prepared based on a survey he conducted. There is now this compilation of what is happening internation-

ally in policy, programs, and research on health literacy. The next version of the report will focus on the United States. In addition to what Baur mentioned, then, these papers are another tool for better understanding what is going on in health literacy.

Ratzan said that the Journal of Health Communication also provides information about health literacy efforts. Also, the U.S. Agency for International Development is holding a summit in December 2012 on social and behavior-change communication.11 The extent to which health literacy is highlighted will depend on the strength of the evidence.

BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation). 2012. More mobiles than humans in 2012, says Cisco. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-17047406 (accessed March 13, 2013).

Cabe, J., and S. Thompson. 2012. From policy to implementation. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2012. Become a Text4Baby partner. http://www.cdc.gov/women/text4baby (accessed November 26, 2012).

ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council). 2009. Implementing the internationally agreed goals and commitments in regard to global public health. Ministerial Declaration—2009 High-Level Segment. Geneva, Switzerland: ECOSOC.

Editorial. 2012. Lancet 380(9840):447. Emanuel, E. 2012. In medicine, falling for fake innovation. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/27/in-medicine-falling-for-fake-innovation (accessed February 28, 2013).

European Communities. 2008. High-level pharmaceutical forum 2005-2008. Brussels: European Communities.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. HHS releases National Plan to Improve Health Literacy. http://www.hhs.gov/ash/news/20100527.html (accessed March 8, 2013).

Johnson & Johnson. 2012. Digital health scorecard. http://www.digitalhealthscorecard.com (accessed November 15, 2012).

Kumaresan, J. 2012. WHO’s health literacy work. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.

Parker, R. 2009. Measuring health literacy: What? So what? Now what? Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Measures of Health Literacy, Washington, DC, February 26.

____________________

11 “In December 2012, USAID will hold an Evidence Summit on the theme of Social and Behavior Change. The purpose of this Summit, which will bring together US Government, multilateral and nongovernmental partners, is to distill the most compelling evidence about the impact of social and behavioral change strategies, and to communicate that data for improved health and development decision-making” (http://sph.bu.edu/careerservices/viewjob.aspx?id=2977 [accessed December 3, 2012]).

Pronovost, P., D. Needham, S. Berenholtz, D. Sinopoli, H. Chu, S. Cosgrove, B. Sexton, R. Hyzy, R. Welsh, G. Roth, J. Bander, J. Kepros, and G. Goeschel. 2006. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. New England Journal of Medicine 355(26):2725-2732.

Ratzan, S. C. 2000. Quality communication: The path to ideal health. Joseph Leiter Lecture. National Library of Medicine/Medical Library Association. NLM Lister Hill Center Auditorium, Bethesda, MD, May 17, 2012.

Ratzan, S. C. 2012. Policies and programs promoting health literacy globally. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.

Ratzan, S. C., and R. M. Parker. 2000. Introduction. In National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy, edited by C. Selden, M. Zorn, S. Ratzan, and R. Parker. NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.

Rees, M. J. 2000. Just six numbers: The deep forces that shape the universe. New York: Basic Books.

Treatman, D., M. Bhavsar, V. Kumar, and N. Lesh. 2012. Mobile phones for community health workers of Bihar empower adolescent girls. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health 1(2):224-226.

UN General Assembly. 2011a. Non-communicable diseases deemed development challenge of “epidemic proportions” in political declaration adopted during landmark General Assembly summit. GA/11183. September 19, 2011. http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/ga11138.doc.htm (accessed November 15, 2012).

UN General Assembly. 2011b. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/66/L.1 (accessed March 8, 2013).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2006. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2011. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.