Health Literacy Policy and Programs

Sandra Vamos, Ed.D., Ed.S., M.S.

Senior Advisor on Health Education and Health Literacy for

the Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Control

Public Health Agency of Canada

Vamos said that the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is the main public health agency in that country and could be seen as equivalent to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For the past 2 years, the PHAC has been linking health literacy work with agency, branch, and center public health objectives. Approximately 60 percent of adult Canadians have low levels of health literacy, with certain populations experiencing much lower levels. These vulnerable populations include older adults (approximately 88 percent of seniors have low levels); the aboriginal populations; and recent immigrants and those with lower levels of education, socioeconomic status, and low English and French proficiency. To improve health literacy, Vamos said, one must improve the knowledge and skills of the populations who receive health information programs and services as well as those who provide such programs and services.

Health literacy efforts in Canada have been anchored in health promotion efforts and have not been driven by the medical system. Recognition is growing that health literacy plays an important role in public health initiatives, Vamos said. As an emerging field, there are many pockets

of innovative health literacy programs, initiatives, and activities across Canada and stronger research on health literacy has been evolving. However, there are no governmental policies that are specific to health literacy at any level of government in Canada and there is little private-sector engagement, Vamos said.

The Canadian path to health literacy began in the 1980s with the Ontario Public Health Association project on literacy and health. This led to interest by the Canadian Public Health Association and a national conference on literacy and health. A second national conference was held in 2004, during which delegates called for the establishment of an expert panel on health literacy. The panel began its work in 2006 and issued its report, A Vision for a Health Literate Canada: Report of the Expert Panel on Health Literacy, in 2008. Data used in drafting the report came from a health literacy scale used in the International Adult Literacy and Skills Survey (IALS) of 23,000 Canadians. The report recommended a pan-Canadian strategy for health literacy and called for policies, programs, and research to increase low levels of health literacy and reduce disparities in health. In 2010 the Canadian Medical Association passed two resolutions to promote health literacy. The first resolution urged governments to develop a national strategy to promote the health literacy of Canadians; the second one addressed raising health literacy awareness of physicians in clinical practice.

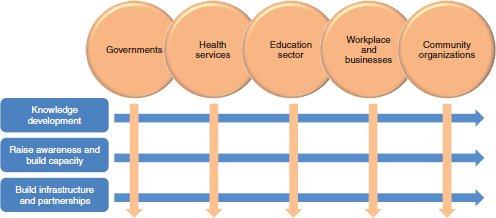

Vamos went on to say that in 2012 the Public Health Association of British Columbia issued a discussion paper, An Intersectoral Approach for Improving Health Literacy for Canadians, which is a framework for action. It is guided by the following vision: “A health literate Canada in which all people in Canada can access, understand, evaluate and use health information and services that can guide them and others in making informed decisions to enhance their health and well-being” (Mitic and Rootman, 2012). The mission of the intersectoral approach is “to develop, implement and evaluate an approach that will support, coordinate and build health literacy capacity in Canada.” Figure 4-1 presents a conceptual model of the intersectoral approach. The three fundamental components are identified on the left and deemed essential for the development of a comprehensive approach or strategy for improving health literacy. A list of objectives has also been developed for each component, and associated sample activities (relevant and effective actions for each) have been suggested, which can be found in the approach document. The five collaborative partners or sectors involved are displayed across the top. Within each sector, individuals, groups, and organizations are invited to develop recommendations related to each objective for what can be done to move health literacy forward throughout Canada.

There are a number of health literacy projects in which the PHAC has

FIGURE 4-1 An intersectoral approach to health literacy.

SOURCE: Vamos, 2012.

been quite active, including the health literacy scan project,1 the health literacy examples in the field project,2 and Learning for Health3—the health literacy embedded learning demonstration project. There are also online health literacy modules for public health professionals. A PHAC module is anticipated to be launched in French and English in the spring of 2013, Vamos said. The Canadian Medical Association, the Canadian Nurses Association, and others worked together to develop a module that was launched in both official languages in 2012.

Vamos said the objectives of the health literacy scan, which was conducted by the University of British Columbia, were to address the following questions:

- What examples exist of noteworthy health literacy activities at a federal or national level in Canada and a set of comparable countries?

- What have been the successes, areas of innovation, and challenges of those activities?

____________________

1 See http://blogs.ubc.ca/frankish/selected-projects/health-literacy-scan-project (accessed December 10, 2012).

2 This project showcases examples of health literacy activities across Canada (http://www.ihahealthliteracy.org/files/DDF00000/Vamos-Canadian%20Health%20Literacy%20Examples%20in%20the%20Field%20Project%20-%20Final%20Apr%2027%202012.pdf [ac cessed December 10, 2012]).

3 “The goal of Learning for Health is to design, pilot test and evaluate embedded learning approaches to improve health literacy outcomes across a range of populations and settings” (http://hpclearinghouse.net/blogs/hlel/pages/home.aspx [accessed December 10, 2012]).

- What are the emerging opportunities and responsibilities for divisions, agencies, and organizations to address the area of health literacy?

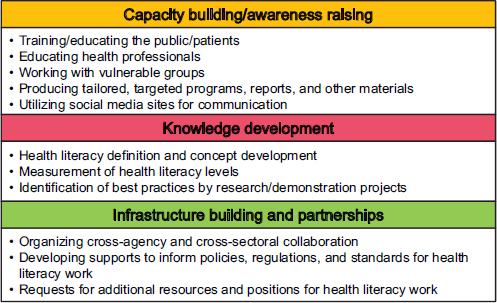

The scan involved looking at federal government initiatives and perspectives of federal employees engaged in health literacy work, an examination of what is happening in Canadian health literacy outside of the government, and a scan of what is happening outside of Canada. Key findings from the scan can be seen in Figure 4-2.

The Canadian health literacy examples from the field project gathers a range of peer-nominated health literacy projects using the Canadian definition of health literacy, Vamos said. This definition is “Health literacy is the ability to access, understand, evaluate, and communicate information as a way to promote, maintain, and improve health in a variety of settings across the life course” (Rootman and Gordon-El-Bihbety, 2008). Three- to five-page vignettes were prepared on the identified projects and will be placed online to share with others. There are 33 projects across Canadian provinces, territories, and regions. They address different settings (e.g., schools, libraries, and workplaces), have different foci (e.g., oral health and mental health), and address different populations (e.g., aboriginals, children and youth, families).

FIGURE 4-2 Key findings: types of health literacy initiatives in Canada.

SOURCE: Frankish et al., 2011.

Learning for Health, the health literacy embedded learning demonstration project, has three demonstration sites and works with three different vulnerable groups (urban seniors, rural families, and urban immigrants and refugees). The goal of this 18-month project was to build capacity. A key finding of the project was that organizations and their staff need time and learning resources to build capacity of staff across all levels to become health literate.

Vamos concluded her presentation with the following examples of potential work that could be done in Canada: (1) develop supports and materials to inform policies and legislation; (2) increase availability and accessibility of resources that could lead to further action within a supportive environment; and (3) create clearer incentives and rewards for engaging in health literacy work.

HEALTH LITERACY AS PART OF A NATIONAL APPROACH TO SAFETY AND QUALITY OF LIFE

Nicola Dunbar, Ph.D.

Program Manager

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care

Dunbar said that the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, established in 2006, is a national, government-funded body that aids and coordinates safety and quality nationally for both the public and the private sector, and for acute and primary care. It is a small organization (about 40 staff) that works through consultation, collaboration, dialogue, and discussion. The key functions of the commission are to

- set national standards;

- develop accreditation schemes;

- develop data and indicators;

- monitor, report, and publish; and

- provide knowledge and leadership for safety and quality.

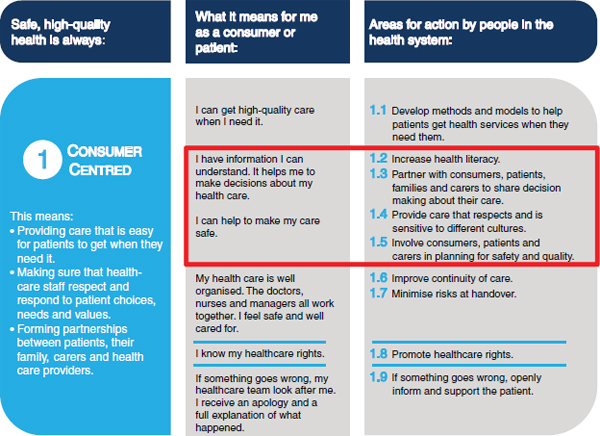

The Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Health Care was developed by the commission in 2010 and endorsed by the health ministers. The vision for safe and high-quality care has three components: it is consumer-centered, driven by information, and organized for safety. The framework provides actions that health care systems should take and, as can be seen in Figure 4-3, several of the actions in the consumer-centered component relate to health literacy: making sure people have information they can understand, are involved in their own health care, receive

FIGURE 4-3 Consumer-centered component of the Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Health Care.

SOURCE: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2010.

services that are sensitive to their culture, and are involved in planning for safety and quality.

The Australian Safety and Quality Goals for Health Care support the framework and contribute to achievement of its vision. The goals address the areas of importance that are amenable to national action and on which efforts should be focused during the next 5 years. Actions are those that can be taken by government, providers, health services, hospitals, patients and caregivers, and the commission. The three high-level goals for safety and quality are

- Safety of care: People receive their health care without experiencing preventable harm. There are a number of priority areas for this goal, including medication safety and health care–associated infection.

- Appropriateness of care: People receive appropriate, evidence-based care. The two priority areas are stroke and acute coronary syndrome.

- Partnering with consumers: There are effective partnerships between patients, consumers, and health care providers and organizations at all levels of health care provision, including planning and evaluation.

For each of the goal priority areas, the framework identifies a number of outcomes desired during the next 5 years. Table 4-1 provides an example of health literate outcomes for effective partnerships. In the area of partnering with consumers, identified outcomes include

- Consumers are empowered to manage their own condition, if clinically appropriate and desired. The focus is on chronic disease self-management.

- Consumers and health care providers understand each other when communicating about care and treatment.

- Health care organizations are health literate organizations. This area picks up on work that has been done at the Institute of Medicine on the attributes of a health literate organization. Outcomes in this area can be seen in Table 4-1.

- Consumers are involved in a meaningful way in the governance of health care organizations.

The final part of the Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Health Care that makes reference to health literacy is the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (NSQHSS). Accreditation and accreditation reform has been a core part of the commission’s work since

TABLE 4-1 Examples of Health Literate Organization Outcomes

|

Goal 3 |

That there are effective partnerships between consumers and healthcare providers and organisations at all levels of healthcare provision, planning and evaluation. |

|

Outcome 3.0.3 |

Healthcare organisations are health literate organisations. |

|

What would success look like after 5 years? |

Healthcare organisations are designed in a way that makes it easier for consumers to navigate, understand, and use their information and services. |

|

How will we know that success has been achieved? |

By monitoring changes in consumer experiences of health literacy barriers through patient experience surveys. |

|

What actions are needed to reach these outcomes? |

|

|

Possible actions by consumers |

Consider being involved in the development and review of consumer information and resources. Consider being involved in the planning, design, and delivery of policies, strategies, and projects to reduce barriers to health literacy within their healthcare organisation. Provide feedback to their healthcare organisation on the accessibility of the organisation’s physical environment or information. |

|

Possible actions by healthcare providers |

Provide feedback to the healthcare organisation on their experience of barriers to health literacy within the healthcare organisation. Participate in improvement projects aimed at reducing barriers to health literacy within the healthcare organisations’ physical environment and information. Use health literacy strategies to improve healthcare safety and quality and encourage colleagues to do the same. |

|

Possible actions by organisations that provide healthcare services or support services at a local level |

Develop and implement health literacy policies and processes that aim to reduce complexity of information materials, the physical environment and local care pathways (NSQHSS 1.18). Establish consumer engagement strategies within the organisation (NSQHSS 2.1 and 2.2). Undertake an audit of the organisation’s materials and environment to identify and eliminate barriers to health literacy (NSQHSS 1.18). Partner with consumers using a variety of techniques when designing information and services (NSQHSS 2.4). Use health literacy design principles when designing information and services (NSQHSS 1.18). Develop targeted health information materials and resources for local population groups with identified health literacy barriers and involve consumers in this process. Embed health literacy considerations into all planning, implementation, evaluation and safety and quality improvement processes. |

|

Possible actions by government organisations, regulators and bodies that advise or set health policy |

Establish health literacy and consumer engagement strategies within the organisation. Embed health literacy principles into all policies. Explore options for including implementation of strategies to address health literacy as a core requirement of healthcare service design and delivery. Support the design and delivery of policies, pathways and processes that reduce the complexity involved in navigating the health system including across sectors and settings. |

|

Possible actions by education and training organisations |

Include health literacy strategies in undergraduate, postgraduate and ongoing professional development education and training for healthcare providers. Produce healthcare providers who understand the health literacy barriers for their patients and have the skills to employ strategies to address those barriers. |

|

Possible actions by research and information organisations |

Investigate the most effective environmental health literacy strategies relevant to the Australian healthcare system. Develop and disseminate clear summaries of health literacy research for consumers. Establish policies and implement processes to involve consumers in research and research translation. Non-government organisations support the provision of peer support, information and education materials to strengthen consumer understanding of their health care and the health system. |

|

Possible actions by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care |

Support the development of a national network aimed at sharing information on health literacy initiatives including environmental and organisation based health literacy strategies. Support the development of tools and resources identifying health literacy strategies and processes which can be implemented at a healthcare organisation level. Support the development and dissemination of measurement and audit tools and resources identifying health literacy barriers. |

| NOTE: NSQHSS = National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. SOURCE: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2012. |

|

its inception in 2006. The central components of the commission’s work in this area include developing safety and quality standards and coordinating accreditation nationally. While accreditation has existed for a long time in Australia, until the commission became involved there was no consistent set of mandatory safety and quality standards for all hospitals and data procedure services. The commission’s approach is to move away from an accreditation process that is seen as checking a list of processes to one where the standards provide the basis for continuous quality improvement. The commission standards are mandatory and will be used for assessment beginning in January 2013.4

There are two overarching standards that address governance for safety and quality, and partnering with consumers, Dunbar said. The other eight standards cover what one might expect from a patient safety perspective: health care–associated infection, medication safety, clinical handover or handoff, patient identification, use of blood or blood prod-

____________________

4 As of January 1, 2012, the standards became mandatory for all public and private hospitals as well as data procedure services.

ucts, pressure ulcers, falls, and deteriorating patients. Health literacy is not explicitly included in the standards; however, throughout the standards are issues that relate to health literacy. Some, but not all of these, are the following:

- 1.18 Implementing processes to enable partnership with patients in decisions about their care, including informed consent to treatment

- 2.4 Consulting consumers on patient information distributed by the organization

- 2.5 Partnering with consumers and/or caregivers to design the way care is delivered to better meet patient needs and preferences

- 4.15 Providing current medicines information to patients in a format that meets their needs whenever new medicines are prescribed or dispensed

Between December 2011 and March 2012, the commission collected information about activities in health literacy in Australia. This was not a systematic or comprehensive process, Dunbar said. There were 66 submissions with more than 200 separate initiatives reported. There are many different approaches to improve health literacy or reduce barriers being taken by many different organizations. Yet, these activities are fragmented, Dunbar said, with few opportunities for learning and sharing information.

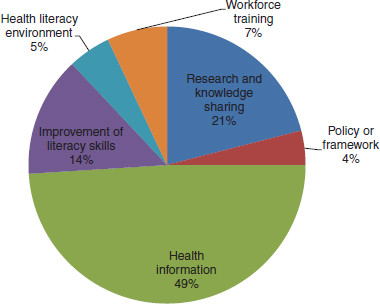

The types or strategies taken can be seen in Figure 4-4. There were few policy approaches to health literacy, although one of the state governments in Australia does have a health literacy policy. Most of the initiatives focused on health information for specific target groups, such as fact sheets for people with disabilties or radio campaigns for different ethnic groups. A number of projects looked at skills improvement. An example in this category was a project working with people who had a chronic illness to develop their self-management capabilities. Some projects focused on workforce training and capacity building. The research and knowledge sharing initiatives included projects such as measuring health literacy, evaluating decision support tools, and measuring effectiveness of information resources.

Dunbar concluded her presentation by describing next steps. These include determining how to more specifically build health literacy into the standards, and focusing on health literacy as a core component of safe and high-quality care, Dunbar said. She concluded that the main approach is likely to be focused on supporting health services to make it easier for people with low health literacy to use and understand health information and health services.

FIGURE 4-4 Types of health literacy strategies and approaches.

SOURCE: Dunbar, 2012.

HEALTH LITERACY IN ITALY’S EMILIA ROMAGNA REGION

Federica Gazzotti, Ph.D.

Director of Communication Staff

Reggio Emilia Health Trust

Gazotti said that the Emilia Romagna region is in the north of Italy. It is the region that produces Parma ham, Parmesan cheese, and Ferrari cars. It is also, as is the rest of Italy, facing a severe economic crisis, she said, and the government is implementing a spending review to reduce public expenditures.

In Italy, the regions and the national government guarantee all citizens universal and equal access to health care. The Regional Health Service with which Gazzotti is associated includes 11 local health trusts, 4 university hospital trusts, and 3 research hospitals. It employs 62,527 people, of whom 3,176 are general practice physicians and 602 are contracting pediatricians, she said. In terms of demography, there are 4,432,439 residents in this region, of whom 13 percent are recent immigrants, mainly from Albania, China, India, Morocco, and Romania. People over 65 years of age make up 22.3 percent of the population.

Gazzotti said that data from the 2008 Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey showed that the adult population of Italy is ranked second from

the bottom among the countries surveyed in terms of health literacy skills. The average literacy skill level in Italy is below the one required to fully access, understand, and use written medical material or to have health-related conversations with doctors and nurses. She hypothesized that one of the reasons for this may be that, in Italy, half of the adult population leaves school with only a middle-school diploma.

In 2008, the Reggio Emilia Local Health Trust’s General Directorate instituted a working group on health literacy techniques. Then, in 2011, the idea of a regional group focused on health literacy and defining needed activities was proposed to the Regional Health Service. The 11-member regional group is composed of the communication directors of the local health trusts and hospitals and the training manager and communication manager of the regional health system, Gazzotti said.

There is a mismatch between the skills of the public and the demands of the health system, Gazzotti said. Therefore, the main objective of this group is to improve the oral and written communication skills of health professionals. Dr. Rima Rudd worked with Gazotti to develop and hold a regional training session composed of two separate weeklong workshops that focused on the communication skills for hospital oncology units. The workshops were held in November 2011 and February 2012. There were 74 participants in these courses. Each Health Trust sent one doctor, one nurse, one communication person, and one person from the front office to the workshop. There were lectures and discussions, exercises and group work, field exercises, and reports.

For the clinicians, special attention was paid to the imbalance between the expectations of the system and the skills of the patients, Gazzotti said. Action options, such as teach-back and shame-free environments, were explored. For the communication attendees, critical issues addressed included community relations, communication exchanges, institutional barriers, and analyses of critical texts. Emphasis was placed on language used, and techniques for creating, reviewing, and assessing information materials was explored.

Between the two workshops, homework was assigned, Gazzotti said. The clinicians conducted self-assessments and experimented with the teach-back and question-asking methods. The communication participants assessed critical materials and searched for barriers in the environment. These assessments indicated several areas of need, including the need for tools for assessment and measurement tools, training for all levels of staff, skill building for materials development, and policy change. Participants in the workshops thought that staff training should be mandatory for people who work in hospitals. They also emphasized the importance of commitment at the regional level, Gazzotti said.

Following the two workshops, the decision was made to imple-

ment two parallel paths of effort in oncologic care (breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer) in each Regional Health Trust. One path focuses on the professional–patient relationship, with training courses to improve relational skills. In this path, clinician participants in the regional course are trained to teach their colleagues in each Local Health Trust. There will be repeated courses because the aim is to train all the health professionals working in the three oncological sectors, Gazzatti said.

The second path focuses on using partnerships with patients and relatives to assess existing materials. Information will be reviewed, first at the local level and then a second time at the regional level in order to create a regional template that can be customized by the region. The emphasis is on the identification of key information and development of explanations in clear and simple language.

Gazzotti said that the goal, by the end of 2012, is for each Local Health Trust to have held a 2-day training course for clinicians working in the oncological field using the peer training method described above. A second goal is to complete the materials assessment by the end of 2012.

Gazzotti concluded by saying that the Regional Health Department is working to become a health literate organization. Every year, the Regional Health Department develops goals that Health Trusts must achieve. This year those goals include the development of health literacy attributes for Health Trust directors, Gazzotti said.

Jennifer Lynch, M.A.

Projects Coordinator

National Adult Literacy Agency

Ireland has a population of 4.5 million, Lynch said, and the country is currently experiencing a baby boom, with the highest birthrate in the European Union. Ireland also has an aging population and a diverse population of immigrants (12 percent of the total population) from many countries, including Poland, Lithuania, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines.

The National Adult Literacy Agency (NALA) is a nonprofit, volunteer organization established 30 years ago, Lynch said. Membership is open to all adults. NALA focuses on five main areas in literacy: policy, research, training, mainstreaming, and promotion and awareness.

While the Department of Education provides some core funding, the organization is independent from the government, which means it can engage in lobbying work. Additional funding for specific projects comes from FAS (the Irish employment authority), the Department of Social and Family Affairs, and the Health Service Executive, which

is responsible for providing health care and social services to the population.

As with many others, funding for NALA activities is very tight, Lynch said. Seventy percent of the education and health budgets in Ireland go to paying for staff, she said. That leaves only 30 percent of the budget for discretionary spending on such programs as those sponsored by NALA.

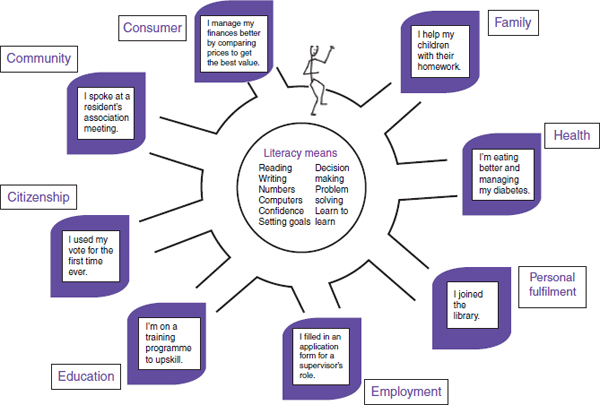

Literacy involves listening and speaking, reading, writing, numeracy, and using everyday technology to communicate and handle information, Lynch said. The definition of health literacy that NALA uses is, “Health literacy emerges when the expectations, preferences, and skills of individuals seeking health information and services meet the expectations, preferences, and skills of those providing information and services.” It includes more than the technical skills of communication (reading, writing, and math), Lynch said. It also has personal, social, and economic dimensions. Figure 4-5 provides an illustration of how an individual uses literacy skills throughout life.

In Ireland, Lynch said, there are 55,000 adults attending local vocational education activities, Lynch said. The Vocational Education Committee (VEC) is the main body responsible for providing adult literacy services nationwide. Professionally trained tutors with support from volunteers provide the training. Individuals usually start out in one-on-one sessions and then move into group sessions when ready. A member of the public who wishes to improve his or her literacy skills contacts the local VEC, which then conducts an assessment and provides the teaching. Lynch said that accreditation for people with relatively weak literacy skills is available following training and that this is an important development.

In 1997, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) conducted an International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) and published a report in 2000 (IALS, 2000). The survey tested the skills necessary to understand everyday material such as a bus timetable and the text on a packet of aspirin. For the aspirin packet, respondents were asked to read the packet and then answer questions such as, “How many days can you safely take these tablets?” Twenty-three percent of the Irish population could not answer that question correctly, Lynch said. These results provided data to support the concerns of health care providers who were calling NALA and saying that they did not think their clients were understanding medication instructions. New data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) are forthcoming in 2013.

NALA contacted the Department of Health and Children to work with them to come up with a strategy to address health literacy issues. The strategy was developed and put forth in the report The National Health Promotion Strategy (Department of Health and Children, 2000). This report

is, Lynch said, the most important health literacy publication in Ireland because it was the first paper that acknowledged health literacy and talked about literacy being a barrier to health promotion. The strategy was launched in 2002, and since that time, NALA has developed health literacy initiatives that have been funded by the Health Promotion Unit of the Department of Health and Children.

One strategy focuses on plain English. More than 300 communicators have been trained in using plain English. The plain English strategy is frequently used for national strategies. One example is a national breast screening program where staff are literacy-friendly and the material has been developed using health literacy principles.

Another strategy is to produce health literate teaching materials, such as The Health Pack: Resource Pack for Literacy Tutors and Healthcare Staff (NALA, 2004). These materials are prepared by health promotion staff working with literacy staff. NALA has also produced the Literacy Audit for Healthcare Settings (Lynch, 2009), a health literacy tool for use in clinical settings. The publication focuses on translating health literacy into practical steps, Lynch said.

Objectives of the Irish health literacy program are to develop understanding of health literacy issues among key health stakeholders, share best practices across the health care sector, highlight and support good practice, and develop government debate and policy in the area.

In 2007, NALA was approached by Merck Sharp & Dohme to develop a collaboration promoting health literacy in Ireland. The collaboration has developed a health literacy website (www.healthliteracy.ie) and has instituted Crystal Clear Awards5 for health practitioners who make their material and practices literacy-friendly.

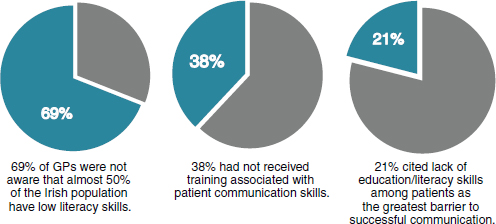

NALA received funding from the national lottery so that it could take part in the European Health Literacy Survey. Results of that survey show that 40 percent of the Irish public has weak literacy skills, with only 21 percent having excellent skills. Merck Sharp & Dohme supported a number of road shows to publicize the findings of the survey and engage in plain English training, Lynch said. In 2008, Merck Sharp & Dohme also sponsored a survey on health literacy awareness among 1,000 general practitioners. The results (see Figure 4-6), Lynch said, were fairly depressing.

Lynch said that future efforts in health literacy in Ireland need to focus on five areas. First, Irish research to provide Irish solutions is needed. One area of focus for research is the literacy demands of Irish health care settings. Second, health literacy needs to be integrated into all national

____________________

5 “The Crystal Clear MSD Health Literacy Awards are designed to recognise and reward excellence in health literacy in the healthcare sector” (http://www.healthliteracy.ie/crystal-awards/why-enter [accessed December 12, 2012]).

FIGURE 4-6 Health literacy awareness among general practitioners in Ireland.

NOTE: GPs = general practitioners.

SOURCE: Lynch, 2012.

health campaigns and screening projects. Third, health literacy needs to be integrated into training at the undergraduate level for range of practitioners. Fourth, incorporating health literacy into health care accreditation is desirable. Finally, she said, there needs to be a national awareness campaign about the problem of low health literacy.

It will be important, Lynch said, to incorporate health literacy into future Department of Health and Children strategies. The department will launch a public health strategy and it is hoped that health literacy will be mentioned in that because it is, in effect, a refreshed health promotion policy. Other opportunities include strategies in the areas of development of primary care structures and of professional competency for general practitioners, she said.

Benard Dreyer, a Roundtable member, said that much of the workshop discussion had focused on practice and moving ideas into action. Where, he asked, should the first steps be taken? Should they be in health care organizations? Should they be in the public health arena? Should they focus on some broad area of disease or prevention? Where do we start in trying to move the needle toward health literate health care?

Dunbar responded that the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has also been wondering where to begin because issues of health literacy seem to be such a huge problem. Although it is recognized that health literacy is an important aspect of high-quality care,

where can one begin to do something? For a long time, the problem was looked at as a public health and health promotion issue, she said. But once health literacy was seen as an issue on which health services can take action, the organization has begun to move forward, Dunbar said. Raising the profile of health literacy nationally is important and is a strategy that was successful in other areas of commission work, she said.

Gazzotti said that the regional health service she works with had to decide between beginning its efforts in a chronic disease such as diabetes or focusing on cancer. Cancer was chosen because it is a well-defined area. The aim is to extend training to other sectors and also to public health.

Lynch said that it is important to find out who is ready for health literacy because timing is important. A new government took office in Ireland 2 years ago. They are busy producing their own policy papers and health strategies. When new national or health strategies are developed, it is easier to incorporate health literacy from the beginning than to try to add it later. Start reading policy papers and action papers, start examining new health initiatives, she said.

Vamos said she thinks an intersectoral approach is a step in the right direction. While there are pockets of health literacy across Canada, the nexus of activity is in British Columbia, largely because there is a health literacy network there which is, in reality, a network of networks and includes a mental health network, a library network, and a seniors’ network. This intersectoral work provides momentum and infrastructure, she said. For example, the mental health network has a health literacy director, funding, and a provincial mandate and strategy for mental health literacy work.

George Isham described some of the ideas he gleaned from the presentations. One point is the importance of defining health literacy in a way that is appropriate to the individual country and the local population and culture. There are also economic constraints to moving forward. Three presenters talked about the attributes of health literacy. There was also an Institute of Medicine discussion paper that described the attributes of a health literate organization. Sharing these ideas is a good way to move forward. Also important, he said, was the idea that expertise should be shared among those involved in health literacy.

Baur said that in the past few years she has presented the U.S. National Action Plan for Health Literacy in three different international contexts with resulting interesting conversations about cultural specificity. She wondered whether it was possible for each country to identify something about health literacy that is specific to its culture.

Roundtable member Susan Pisano said that all four presenters on the panel mentioned immigrant populations. One of the challenges in the United States is diversity and making sure attention is paid to the cultural

differences among the population. How is that done in the countries represented on this panel?, she asked.

Gazzotti said that the region she is from in Italy has developed a sophisticated system of mediators in every hospital and in primary care. These mediators speak in ways that the immigrant can understand. They use everyday language to explain things and translate material into everyday language. But that does not happen for the Italian population. The Italians do not receive information in everyday language, nor is the material in everyday language because it is assumed they understand what they are given.

Wilma Alvarado-Little, a Roundtable member, said that a big issue in the United States is the limited resources available for translating and disseminating information to many very diverse populations. Are there particular strategies the can be used to address this issue?

Lynch said that in Ireland there was a translation fund that health writers could use to pay for the translation of national information leaflets. That fund, however, has dissipated in the last few years. As a result, organizations of different minority populations are working to help their colleagues translate material into other languages.

Thomas Sang from Merck Sharp & Dohme said that the U.S. health care market seems to be shifting from a fee-for-service environment to a much more holistic payment policy with many delivery and payment reforms. Some of the newer payment policies are looking at value-based purchasing and quality measurement of the way in which care is delivered. Sang said that until recently he was involved in developing quality measures at the federal level. They were thinking about how to develop measures for assessing patient engagement and shared decision making. He asked whether any of the panelists are using measures to evaluate provider engagement of patients and what type of clinical quality measures are being used.

Gazzotti, Vamos, and Lynch said that is not happening in their countries. Dunbar said the discussion was beginning in Australia. There is a new pricing model for public hospital services—the efficient price. Initially this was conceived of as including measures of safety and quality and the patient experience. However, such measures were not included in the initial draft of the efficient price. There are some agreed-upon national indicators around safety and quality, Dunbar said, and work is beginning for the area of patient experience.

Building on the previous question, Isham asked whether the panelists anticipate health literacy meaurement as part of accreditation. Lynch said that Ireland’s accreditation system is quite new but provides a good opportunity to develop a credible way of measuring communication. Dunbar said that each item in the standards in Australia will be marked

as met with merit, met, or not met. They do not examine the detail of what communication might look like, but starting a conversation on this is something the commission would like to do.

Andrew Pleasant, a Roundtable member, asked how efforts such as this Roundtable discussion could be kept going internationally. How can best practices be shared yet still allow for the localization of those practices to fit the specific culture in which they will be used?

Kristine Sørensen from Maastricht University said that nine countries and many other partners are working on the European Health Literacy Survey. One issue confronted is how to translate the word literacy since this has different meanigs for different countries. In many of the European languages, literacy is changed into health competencies. In response to Pleasant’s question, she said, this meeting is hopefully just the first step in a global dialogue. Sørensen said that she and a colleague from the United Kingdom launched a small survey to find out what individuals thought might be an international platform for health literacy. She said she would be happy to distribute it to the audience members in order to obtain their input.

Diane Levin-Zamir said the International Union of Health Education and Promotion has a global working group composed of people who want to work together on different aspects of health literacy. This might be a mechanism for communication and sharing more globally.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2010. Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Health Care. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Australian-SandQ-Framework1.pdf (accessed December 11, 2012).

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2012. Partnering with consumers: Action guide.

Department of Health and Children. 2000. National Health Promotion Strategy. http://www.injuryobservatory.net/documents/National_Health_Promotion_Strategy_2000_2005.pdf (accessed December 13, 2012).

Dunbar, N. 2012. Health literacy as part of a national approach to safety and quality. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.

Frankish, J., D. Gray, C. Soon, and D. Milligan. 2011. Health literacy scan project report. Ottawa, ON: Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Control, Public Health Agency of Canada.

IALS (International Adult Literacy Survey). 2000. Literacy in the information age: The final report of the International Adult Literacy Survey. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Lynch, J. 2009. Literacy audit for healthcare settings. NALA: Dublin, Ireland. http://www.healthpromotion.ie/hp-files/docs/HSE_NALA_Health_Audit.pdf (accessed December 13, 2012).

Lynch, J. 2012. Health literacy in Ireland. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.

Mitic, W., and I. Rootman, editors. 2012. An intersectoral approach for improving health literacy for Canadians. Victoria, BC, Canada: Public Health Association of British Columbia.

NALA (National Adult Literacy Agency). 2004. The Health Pack: Resource pack for literacy tutors and healthcare staff. Dublin, Ireland: NALA. http://www.nala.ie/resources/health-pack (accessed December 13, 2012).

Rootman, I., and D. Gordon-El-Bihbety. 2008. A vision for a health literate Canada: Report of the Expert Panel on Health Literacy. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Public Health Association.

Vamos, S. 2012. Health literacy in Canada. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.