Innovations in Health Literacy

HEALTH LITERACY IN ISRAEL: POLICY, ACTION, RESEARCH, AND BEYOND

Diane Levin-Zamir, Ph.D., M.P.H., MCHES

National Director, Department of Health Education and Promotion

Clalit Health Services

Lecturer, School of Public Health, University of Haifa, Israel

Levin-Zamir began with introductory data about Israel, a country with significant cultural diversity. About 20 percent of the people who live in Israel are Arab-speaking. Another 20 percent are native Russian speakers. Many of the remaining 60 percent have immigrated from other countries. A growing number of residents are Hebrew-speaking from birth. The diversity of cultures presents a tremendous challenge for health services, health literacy, and health promotion, Levin-Zamir said.

Life expectancy in Israel is 82 years, Levin-Zamir said. There is universal health care coverage for all citizens of Israel, which includes primary, secondary, and tertiary care. In terms of risk factors, 20.9 percent of people smoke, more than 60 percent are overweight or obese, and only 20 percent to 30 percent engage in regular physical exercise. Arab women and religious men and women are the least physically active, Levin-Zamir said. The average number of physician visits is about six to eight per capita. Rates of chronic diseases are growing and there is concern about increases in out-of-pocket expenses, which may contribute to disparities in health.

Israel has a literacy rate of 97 percent; it ranks 17th among 192 countries for digital communication; and 68 percent of households regularly use the Internet. Two definitions of health literacy have been used in Israel. The first is one developed by Nutbeam (1998), which defines health literacy as “the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health.” The second, developed by Ratzan and Parker (2000), defines health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”

There is not yet a national overall initiative for health literacy in Israel; however, there are several policy landmarks that are encouraging, Levin-Zamir said. The 2020 development goals and objectives include developmental goals on health literacy. The goals include improving awareness of health literacy on a national level, as well as specifically among elected representatives of the public and journalists through local and media interventions. In addition, the national strategic plan for reducing health disparities includes health literacy. A major challenge is the yet-unfunded mandate of the Israeli director general on cultural and linguistic accessibility in the health system. The mandate specifies cultural mediators, information and signage in four to five languages, simultaneous translation of services, capacity training for health professions, culturally appropriate health promotion in communities, and empowerment and involvement of the community. Finally, the Clalit hospital system has voluntarily adopted the Joint Commission’s international accreditation that includes elements promoting health literacy.

Clalit Health Services is the second-largest nongovernmental health organization in the world, Levin-Zamir said. Figure 5-1 provides data on the system. Health literacy action takes place in many settings, including community/primary care, the hospital, and online. In the community, for example, a program called “Refuah Shlema” (initiated in the late 1990s), aims to promote health and health literacy among new immigrants from Ethiopia. The program is a partnership of Clalit and the Ministry of Health. The program locates, trains, and employs cross-cultural liaisons, mediators, and primary health care providers. An integral part of the team is a cultural liaison serving the Ethiopian population. There are telephone translators, a community diabetes program, and training and coaching health staff on cultural competence skills. The program has been sustained for more than 14 years and is the longest community program for cultural mediation implemented in Israel, Levin-Zamir said.

An evaluation was conducted after the first 5 years of the program.

FIGURE 5-1 Clalit Health Services.

SOURCE: Levin-Zamir, 2012.

Levin-Zamir said that results showed that the program, with no significant increase in expenditure on services, was effective at improving

- physician-patient relations,

- availability and accessibility of medical services, and

- the ability to navigate the health system.

Another area for action in the community is diabetes and chronic illness. A systematic review by Renders and colleagues (2001) found that “no specific intervention, if used alone, led to major improvements in management of chronic diseases.” Complex problems require complex solutions, Levin-Zamir said. Clinical quality indicators for the community have been developed for management of diabetes, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and rehospitalizations. Improvement in these indicators reflect community action in patient empowerment.

A number of health literacy tools have been developed, Levin-Zamir said. More than 3,000 physicians and nurses engage in in-service training each year. Culturally appropriate lifestyle and self-management workshops have been held for the people in the community, with tailored programs for special populations. The program has expanded every year since its inception in 1996. In terms of outcomes, HbA1C1 measures have greatly improved for those who participated compared to those who did not participate, Levin-Zamir said.

____________________

1 HbA1C is a lab test that shows the average level of blood sugar (glucose) over the previous 3 months. The test indicates how well diabetes is controlled in an individual.

There are also actions aimed at health literacy in hospitals. Israel recently joined the World Health Organization Network of Health Promoting Hospitals, Levin-Zamir said. Teaching hospitals, community pediatric clinics, and gynecological clinics have adopted the “Ask Me 3” initiative that encourages each patient to ask three questions. What is my health problem or condition? What am I to do about it? Why is it important? This has been translated into Hebrew, Arabic, and Russian. The teach-back method is also being implemented.

One additional initiative is a program for health literacy online. Health information in Hebrew, Arabic, Russian, French, and Portuguese has been posted online. A user can obtain his or her examination results and an interpretation of what those results mean. Appointments can be made in all languages. There are approximately 2.5 million entries each month, about 80 percent of which are unique entries. To engage children there is an online game about nutrition; this app was the most popular app in all of Israel during the previous month, Levin-Zamir said.

GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer have provided grants for health literacy and capacity building. The grants were used to build a computer-based program called “You Can Make a Difference” with the aim of improving communication skills using the models of motivational interviewing and brief interventions (the five As), applied in different topics in healthy lifestyles, including smoking cessation, nutrition, early detection of breast and colon cancer, and physical activity. More than 1,100 physicians and nurses have participated in the training based on group learning during weekly staff meetings in primary care clinics, Levin-Zamir said.

Israel is building its research base on health literacy, Levin-Zamir said. The first piece of research conducted was on developing and validating a Media Health Literacy (MHL) scale tested among adolescents. Results showed there is an association between MHL and other important aspects of health and empowerment, including family/peer co-viewing, sources of health information, selected health behaviors, health empowerment, and social and personal demographic characteristics.

Israel is also mounting the National Survey on Health Literacy, which is similar to the European Health Literacy Survey. The survey was developed based on focus groups with key informants. This is an in-person survey of a representative sample of 600 people in home interviews. It will be available in four languages: Hebrew, Arabic, Russian, and Amharic.

Levin-Zamir said that in Israel there are tremendous challenges in bridging the health literacy gaps. New and preliminary policy initiatives for health literacy are part of a systems approach to change, with complex action being taken in the community, health service, and media settings. This provides the potential for building a strong evidence base.

Research is in its early stages with promising studies and projects under way, Levin-Zamir said.

Levin concluded with some observations about the future. She recommended that countries should adopt a “health literacy in all policies” approach, collaborate in research, build on the experience of partners and colleagues, and create international initiatives for professional training and capacity building.

THE EUROPEAN HEALTH LITERACY SURVEY

Kristine Sørensen, Ph.D.

Project Coordinator, European Health Literacy Project

Maastricht University

Prior to the European Health Literacy Project little data about health literacy were available at national and cross-national levels, Sørensen said. There was also little funding. Owing to the efforts of a persistent handful of people led by Ilona Kickbusch and Helmut Brand, funding was obtained from the European Commission for a project that began in 2009, Sørensen said. The project was led by the European Health Literacy Consortium, which is a consortium of nine institutes and universities from eight countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain.

There were three aims of the project: to set up national advisory boards on health literacy in the eight countries, to establish a European health literacy network, and to measure health literacy in Europe. Measuring health literacy required developing a questionnaire that could be used in the eight countries. The questionnaire is called the European Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q); it is a conceptually based tool, and it was developed by a multinational cross-disciplinary group of researchers, Sørensen said. The tool is broad in scope and covers health care, disease prevention, and health promotion; it also captures both individual competencies and the complexity of systems.

The tool is both content and context specific and measures the fit or relation of individual competencies, expectations, and experiences versus the situational or contextual demands, expectations, and complexities, Sørensen said. There are three versions of the tool, with the long version, the HLS-EU-Q86, used for the European Health Literacy Survey. There is also a core version (HLS-EU-Q47) and a short version (HLS-EU-Q16). These have been translated into 10 languages, with more language translations in process. They have been used in the European Health Literacy Survey as well as smaller studies of specific target groups.

The process for developing the tool began with defining health lit-

eracy. For HLS-EU, “health literacy is linked to literacy and it entails people’s knowledge, motivation and competencies to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information in order to form judgment and make decisions in everyday life in terms of health care, disease prevention, and health promotion to maintain and improve quality of life during the life course” (Sørensen et al., 2012).

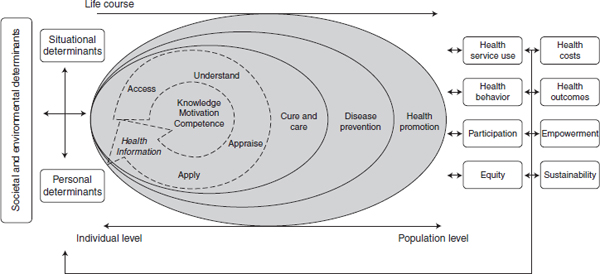

Conceptual models were reviewed, Sørensen said, and the model agreed upon can be seen in Figure 5-2. At the center are the four steps of processing information: accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying information to make decisions. Moving out from the center circle are the three areas of health: health care, disease prevention, and health promotion. On the left side of the figure are the determinants: personal, situational, and broader societal and environmental determinants. On the right side are the outcomes. At the top is the life-course line indicating change over the lifetime. The model captures individual competencies as well as the public health perspective, Sørensen said.

To develop the questionnaire the group laid out a matrix, an example of which is shown in Table 5-1. There are 12 subdimensions of health literacy, so items were developed to measure each of the 12 subdimensions.

The results were analyzed by the Austrian team in the HLS-EU Consortium led by Jürgen M. Pelikan. The 47 health literacy items in the HLS-EU-Q grounded in the HLS-EU matrix above were converted into a 50-point scale that indicated four levels of health literacy:

- Inadequate level: 0–25 points or 50 percent (1/2)

- Problematic level: >25–33 points or 66 percent (2/3)

- Sufficient level: >33–42 points or 80 percent (5/6)

- Excellent level: >42–50 points or top 20 percent (<5/6)

Those who answered “easy” or “very easy” for up to half of the questionnaire would have inadequate health literacy; those who could answer “very easy” or “easy” up to 66 percent of the questionnaire would have a problematic level; those who answered “easy” or “very easy” for up to 80 percent of the questionnaire would be at the sufficient level; and those who answered “easy” or “very easy” for more than 80 percent of the questionnaire would have excellent health literacy.

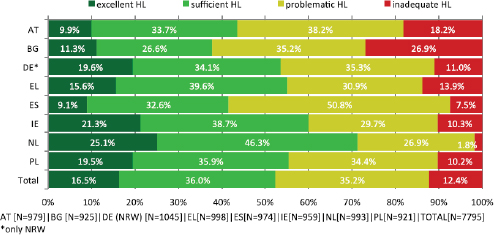

The results are presented in Figure 5-3. The health literacy index for the eight countries involved in the survey showed that 47 percent, on average, have either problematic or inadequate levels of health literacy. However, it varies across the different countries. For example, the Netherlands is doing well, but Bulgaria has the most severe levels of limited health literacy.

Sørensen said that the survey results showed that levels of health

TABLE 5-1 Examples from the HLS-EU Questionnaire

| On a scale from very easy to very difficult, how easy would you say it is to…“very difficult”—“difficult”—“easy”—“very easy”—(don’t know) | ||||

| Health literacy matrix (examples of items) | Access/obtain | Understand | Appraise | Apply |

| Health care | Find information about symptoms that concern you? | Understand your doctor’s or pharmacist’s instruction on how to take prescribed medicine? | Judge how information from your doctor applies to you? | Follow the instructions on medication? |

| Disease prevention | Find information on vaccinations and health screenings that you should have? | Understand why you should need health screenings? | Judge when you should go to a doctor for a health check-up? | Decide if you should have a flu vaccination? |

| Health promotion | Find information on healthy activities such as exercise, healthy food, and nutrition? | Understand information on food packaging? | Judge how where you live affects your health and well-being? | Make decisions to improve your own health? |

SOURCE: Sørensen, 2012.

FIGURE 5-3 Levels of health literacy for the eight countries participating in the European Health Literacy Survey.

NOTE: AT = Austria; BG = Bulgaria; DE = Germany; EL = Greece; ES = Spain; HL = Health Literacy; IE = Ireland; N = number of respondents; NL = Netherlands; NRW = North Rhine-Westphalia (state in Germany); PL = Poland.

SOURCE: HLS-EU Consortium, 2012.

literacy were associated with age, socioeconomic status, and perceived health. In seven of the eight countries (Netherlands is the exception), increasing age is associated with decreasing health literacy. In all countries, there is a strong social gradient, with those with very low socio-economic status having limited health literacy. The survey results also show that those who rate their health as bad or very bad have limited health literacy, Sørensen said.

Research is now being conducted using national data to look at differences among the consortium countries. The hypothesis, Sørensen said, is that a country’s health system and society shapes levels of health literacy. The future research will look at where people find information; who the gatekeepers are; and what the national beliefs, religions, and societal effects of the educational system are.

Health literacy is a challenge in Europe; it varies across countries and is content and context specific, thereby demanding local solutions, Sørensen said. The European Health Literacy Consortium provides a platform for action. The consortium is now being approached for advice by other organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Council of Europe, and by European parliamentarians.

Next steps include working with additional countries to implement the European Health Literacy Survey, Sørensen said. Including health

literacy in the curriculum of educational institutions is another approach being taken and is working with politicians to put health literacy on national agendas. Austria, for example, has made health literacy part of its national health targets.

But when 47 percent of adults have poor health literacy, that is too high, Sørensen said. She concluded that more must be done, and she looks forward to the continuing global dialogue begun at this conference.

HEALTH LITERACY COMMUNICATION(S)

Franklin Apfel, M.D.

Managing Director, World Health Communication Associates Ltd.

It is commonly agreed that there is no universal consensus of what is and what is not a health literacy project or policy, nor a universally equitable means to translate the concept of health literacy, Apfel said. Furthermore, there is no global organization for health literacy and the population of interest is undefined. While many see this as a deficit, from a communication perspective, Apfel said, the lack of consensus about these things has helped enable the field to progress in a unique way.

The process of progression has been more viral than controlled. This has catalyzed a dynamic, growing, changing, and expanding discourse, Apfel said. Initially concerned about the health impacts of low literacy on medical system compliance issues (i.e., medication adherence), the health literacy lens has now been applied in a wide variety of settings (e.g., schools and workplaces) to many broader public health and societal concerns, including inequalities, advocacy, empowerment, community engagement, resilience, and risk reduction. Multiple definitions, approaches to, and champions of health literacy have emerged. This seemingly “chaotic” process has helped position health literacy as a whole-of-society concern and a platform for intersectoral communication and cooperation, Apfel said.

A useful slogan for efforts to further define the field of health literacy is “Don’t hem me in,” an American expression that means be open, not restrictive, Apfel said. Also of critical importance for health literacy–related communications is measurement. The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) pioneering health literacy research efforts and the more recent European Health Literacy Survey have provided critically important evidence of the extensivity, health impacts, and costs of weak health literacy, Apfel said. These data give scientific authority to the area and have been used to support advocacy aimed at raising professional and political awareness of and attention to health literacy. Yet, the potential commu-

nication and advocacy impact of measurement has not been fully realized, Apfel said, because available metrics have not been democratized. Research to date has been too dominated by providers measuring the skills and abilities of individuals (users) and has not adequately empowered people with tools they themselves can use.

Ratzan in an earlier presentation showed a graphic developed by Parker that illustrates how health literacy is a product of the interaction between the skills and abilities of individuals and the demands and complexities of the system within which information is sought and/or obtained (Figure 3-3). There has been some work on measuring the supply side with the use of checklists and health system assessments. What is needed, Apfel said, are tools people can use to hold systems accountable, tools to make sure that institutions, communities, and government authorities invest in creating and supporting more systems that are health-literacy-friendly. Such an approach builds on the old adage that “what gets measured gets done.”

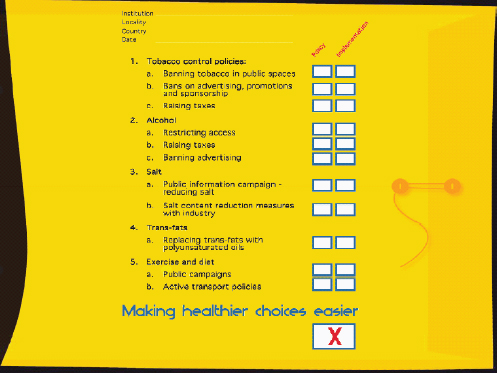

One such tool being explored by some patient associations and Healthy City groups, Apfel noted, is a simple, outcome-focused scorecard. It builds on the WHO’s list of best buys for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), which identifies interventions that have been shown to be effective in terms of cost, saving lives, and reducing suffering. Citizens could use this list as a scorecard (see Figure 5-4) to rate institutions or communities on how well they are doing in enacting these “best buys” related to tobacco control policy, alcohol, salt, trans fat, and exercise. The institutions or communities would get a score: for example, five stars for excellence in all areas, four stars for needing to improve in one. Such a scoring approach would raise awareness of the value of certain policies and could serve as a strong incentive for targeted action, Apfel said.

Individual scorecards are also useful, as Dr. Ratzan pointed out earlier, Apfel said. Scorecards such as the Digital Health Scorecard (http://www.digitalhealthscorecard.com) can help individuals strengthen their health literacy by examining their own key risks, understanding where they need to act, and identifying where resources are available. The Digital Health Scorecard generates a single number score from 0 to 100 for seven common risk factors. The single number makes it easier for people to keep track of their health risks and establishes simple goal ranges. Including a range of medical and health indicators and behaviors helps people create a mental model of how lifestyle choices and NCDs are connected, Apfel said. Having a scorecard that reflects risk and preventability can motivate action, with sequential ratings serving as incentives for improvement. Importantly, Apfel said, the individual scores can be collected so that systems can be informed (and measured) by the aggregated outcome mea-

FIGURE 5-4 Making healthier choices.

SOURCE: Apfel, 2012.

sures of their users. Areas needing attention can be identified and appropriate evidence-based interventions and investments made, Apfel said.

Another important area for health literacy communication is the need to counter misinformation in information marketplaces—the public and private places where people obtain health information (e.g., billboards, media, blogs, leaflets, advertising). There are many examples of disinformation, or, as some say, “health glitteracy,” where risk and hazards, for example, are glamorized and promoted. These groups include the tobacco and arms industry as well as many drinks and fast-food chains, Apfel said. Strengthening health literacy not only means providing reliable, understandable, and accessible information but also requires actively countering the disinformation. This can be done through a combination of regulation, education, and social marketing initiatives. Although a full discussion of these approaches is beyond the scope of this workshop, one key factor in any strategy aimed at countering hazard promotions relates to “framing,” shaping the contexts within which people perceive and understand issues, Apfel said. Those providing disinformation, Apfel noted, know that if one gets people asking the wrong questions,

the answers do not matter—for example, framing tobacco as a rights issue: that is, “the right to smoke.” As long as people see tobacco as a rights issue, Apfel said, those saying one should not smoke (like public health authorities) will be seen as representing the nanny state or health “fascists.” To raise health literacy about tobacco control, the WHO and other public health agencies have worked to reframe perceptions of tobacco and raise awareness that it kills half of its users when used as directed. Immunization is another topic about which there is much misinformation and confusion. Opponents of immunization actively frame the issue around vaccine safety concerns. Agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control have been working on reframing vaccine debates around the issue of protection from the significant diseases that vaccines provide for individuals and populations, Apfel said.

Those working to enhance health literacy can benefit from learning from the rapidly growing expertise and experience of public health communication science, especially in the area of social marketing and audience segmentation techniques, Apfel said. These approaches build communication strategies based on first understanding “customers” and insights into people’s health literacy and how it is influenced by their everyday lives, hopes, fears, values, beliefs, and behaviors. With this knowledge, messages can be shaped and programs tailored to specific groups’ needs and demands. Information can be packaged and delivered in ways that more effectively motivate, inform, and empower individuals to make healthier choices. There are many health literacy campaigns that have used this approach to raise awareness about important health issues. Examples include campaigns related to seat belt wearing in Hispanic populations2 and education initiatives for mothers through Head Start programs on what to do when one’s child is sick.3

Apfel said that the final area he wanted to discuss is the communications revolution. Those interested in improving health literacy need to engage on a continuing basis with new media technologies, tools, and platforms because that is where vast numbers of individuals obtain their information, he said. What influences health literacy is changing. In 2010, the International Telecommunications Union4 reported that two-thirds of the world’s population has mobile telephones. There is also media con-

____________________

2 See http://www.nhtsa.gov/About+NHTSA/Press+Releases/2001/NHTSA+Launches+Campaign+To+Promote+Seat+Belt+Use+Among+Hispanics (accessed November 16, 2012).

3 See http://www.ihs.org/documents/literacy/Conference/Debbie%20Boulware%20O%27Neill%20-%20what%20to%20do%20brochure2012.pdf (accessed November 16, 2012).

4 See http://www.itu.int/newsroom/press_releases/2010/pdf/PR08_ExecSum.pdf (accessed November 16, 2012).

solidation both nationally and globally. Obtaining independent information is more difficult in some respects, Apfel said.

The Internet provides many new platforms. There is the Patients Like Me platform (http://www.patientslikeme.com), where people can communicate with other people who have similar kinds of health conditions and diseases. They can help inform each other and raise each other’s health literacy about available options, Apfel said. There are Facebook pages, such as Vaccinate Your Baby (http://www.facebook.com/VaccinateYourBaby). There are various text programs, for example, the Text4baby program (https://text4baby.org). In this program, the mother registers on a website, sending her ZIP code and due date. Using geocoding and the due date, the mother will then receive messages and referrals to local resources. Topics covered are those critical to maternal and infant health, including breastfeeding, mental health, car seat safety, safe sleep, oral health, pregnancy symptoms and warnings, exercise, developmental milestones, and violence. Another approach is the use of “edutainment,” that is, using soap-opera formats and storybook formats to communicate health messages.

Mobile devices are also important for providers. Apfel said his son, who went to medical school at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School in the United Kingdom, has not used a textbook since his third year in medicine, when all third-year students received handheld devices. He and his fellow students now access all needed health and medical information through their devices.

Apfel said there is a great need for “universal connectors.” Many players and agencies are already taking health literacy–enhancing action in a wide variety of settings, such as schools, workplaces, community-based agencies, political arenas, and in health services and systems. Most do not call these health literacy initiatives. They are often called “education programs,” “health promotion initiatives,” “interpretation,” “translation,” and “cultural adaptation services.” Others relate to helping people navigate complex systems, linking people with needed resources, or connecting them with others like themselves. Many of these health literacy agents do not even know what health literacy is. Those who have had the privilege of engaging with, defining, and identifying the many ways health literacy is a determinant of health have important roles to play as connectors, Apfel said. As health systems work to embrace new governance models (which emphasize whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches), health literacy–related communications provide both a common meeting ground and a way of measuring the success of our individual and collaborative initiatives, Apfel said.

INNOVATIONS FROM A CORPORATE PERSPECTIVE

Innovations—Wellness and Prevention: A Corporate Perspective

Fikry W. Isaac, M.D., M.P.H., FACOEM

Vice President, Global Health Services

Chief Medical Officer, Wellness & Prevention, Inc.

Johnson & Johnson

Isaac described his responsibilities as managing the health and wellness programs for 120,000 Johnson & Johnson employees and their families worldwide, 60 percent of whom are outside the United States. These employees work in 250 operating companies in 75 countries. What brings them together, Isaac said, is the credo, the value system within Johnson & Johnson that was developed and established about 65 years ago by General Johnson. That credo is, “We are responsible to our employees, the men and women who work with us throughout the world.” Johnson & Johnson has a responsibility to provide resources that foster healthier lives, not only to its workers but also to communities and the environment. As Bill Weldon, the former chief executive of the company, said, “Good health is also good business.”

The company’s global health strategy has five components: (1) foster a culture of health; (2) integrate service delivery with innovative solutions that focus on prevention, behavior modification, and linkage to benefit design; (3) use appropriate incentives; (4) include family and the community; and (5) commit in the long term. Promoting and sustaining a culture of health within an organization requires finding approaches that incorporate these five components in such a way that they become part of the fabric of the organization rather than an add-on, Isaac said. Taking a holistic view of the individual and the organization is also key; an organization should offer programs that simultaneously address the mental, physical, nutritional, and spiritual aspects rather than taking one area or one condition at a time. The five-part strategy also uses incentives to get people interested in improving health, but, Isaac said, the way to sustain behavioral changes is to motivate people to make changes in their lifestyle, which has been a key focus in the company’s prevention and wellness programs for the past 30 years.

Also of major importance is to commit for the long term, Isaac said. Employee health goals for 2015 include

- Ninety percent of employees have access to “culture of health” programs.

- Eighty percent of employees have completed a health risk profile and know their key health indicators.

- Eighty percent of measured population health risk will be characterized as low health risk.

The “culture of health” program includes programs and policies related to becoming tobacco free, HIV/AIDs management, how to prevent cancer in the workplace, and how to address healthy eating in the workplace, as well as wellness programs and access to employee assistance counselors. The second and third goals above relate to the individual’s ability to understand and know his or her health risks, and to take action to reduce those risks. Achieving the third goal will demonstrate the impact the program is having on the health of its employees, Isaac said. Progress is tracked with mandated annual reviews. Local teams report progress against goals annually through the online Global Health Assessment Tool. The results for each location feed into a Culture of Health Scorecard, which is reviewed by senior management to raise awareness around progress locally and to facilitate action planning.

The strategy requires offering access for employees to centrally provided resources and tools that make it easier for them to implement programs to improve health. However, one can not address only individual workers’ health, Isaac said; one needs to reach out to the homes and communities where workers live. Programs offered to spouses and families include a health profile, an e-health website, tobacco cessation programs, a family activity challenge, and Weight Watchers®, among others. Meeting people where they are is part of the philosophy in offering programs. This is accomplished through offering multiple approaches to health programs, from person-to-person efforts within the clinic, to fitness or wellness centers and energy break rooms, to e-health messages when the environment allows for such an approach.

Johnson & Johnson also has a population health risk assessment process that tracks 11 indicators: obesity, high cholesterol levels, high glucose, high blood pressure, tobacco use, physical inactivity, high stress levels, high alcohol use, unhealthy eating, no use of seat belts, and depression. The risk assessment profile is offered in 19 countries and 18 languages and has been modified as needed to be culturally appropriate. The U.S. program has been in place for more than 30 years, and data show that the low-risk group (those with no more than 2 of the 11 health risks) has risen from 78 percent of the population in 2006 to about 88 percent in 2011.

One approach piloted in the United Kingdom and France was placement in the workplace of kiosks that provide an effective and fast, frontline method of screening large populations for the key health metrics of weight, body mass index, body fat, blood pressure, and heart rate. Results

have been positive, and there is consideration of placing them elsewhere. Other approaches include a digital health coach with a plan for modifying or changing an undesirable health-related behavior that is available 24 hours per day. This approach includes the following:

1. A detailed assessment to understand a person’s unique motivation, confidence, and change barriers

2. A supportive plan for treatment that

a. Establishes an emotional connection,

b. Follows proven clinical guidelines,

c. Incorporates proven behavioral science models,

d. Is uniquely tailored to each individual,

e. Is longitudinal, and

f. Offers tools, tips, and resources

3. Quantifiable outcomes measures

The final innovation area that Isaac discussed was energy management. The Energy for Performance in Life program is designed to achieve optimal performance for the organization and arm employees with personal energy management skills. The practice of energy management can produce employee engagement, resiliency, and the potential for greater employee innovation, creativity, and optimal performance. This program currently reaches 16,000 employees who attend either a half-day, 1-day, or 2-day training session that teaches them how to expand their energy beyond their current status.

Isaac said that in terms of overall impact of the health promotion program on health outcomes and cost in the United States, “company employees benefited from meaningful reductions in rates of obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, tobacco use, physical inactivity, and poor nutrition. Average annual savings were $565 in 2009 dollars, producing a return on investment equal to a range of $1.88 to $3.92 saved for every dollar spent on the program” (Henke et al., 2011).

Isaac concluded his presentation by saying he wished to impart six key messages. First, success springs from a culture of health, which is built into the fabric of business, communities, and health systems. Second, phased approaches and pilots are critical to successful implementation. Third, there must be both short- and long-term goals and measurement of outcomes. Fourth, a focus on health risk factors can yield strong results. Fifth, increased productivity and engagement can generate significant cost savings and improved performance. Finally, investment in prevention and health innovation can yield significant economic and social returns.

Innovations in Health Literacy at Merck & Co., Inc.

Michael Rosenblatt, M.D.

Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Officer

Merck & Co., Inc.

Rosenblatt spoke about what could be industry’s unique role in the health literacy movement and described the journey Merck is taking. One step along Merck’s journey was broadening its perspective—coming to the understanding that its products are not just the “chemical or the mixture that is in the bottle,” but include all of the information surrounding its medicines and vaccines. The “chemical” would be of no use to a physician unless the physician understood what was in it, what it was good for, and what would be the problems or risks in using it, Rosenblatt said. The same is true for patients, especially at critical moments such as when receiving a new diagnosis.

Rosenblatt said company founder George Merck framed up its broad responsibilities to patients very well back in 1950, when he said:

We cannot step aside and say that we have achieved our goal by inventing a new drug…. We cannot rest until a way has been found with our help to bring our finest achievement to everyone.

Stories heard every day show that there is much opportunity to help create better understanding for patients. Rosenblatt said that as an endo-crinologist he has placed many patients on thyroid hormones and told them they must take it every day of their lives because it is substituting for a hormone that normally circulates in the body. But numerous times patients stop taking the medicine when they assumed it might interfere with a newly prescribed antibiotic, for example. Similarly, he noted, patients placed on cholesterol medications sometimes abandon them as soon as their cholesterol reaches appropriate levels.

The challenge is to communicate effectively, in a language that patients can understand, especially at critical times, such as when they are assimilating a new diagnosis. There is a large emotional overlay and, even if the language used is quite right, the patients may not be in a position to accept or understand that language, Rosenblatt said. One must consider people’s state of mind when designing patient information.

The significant challenges faced in health care today place more responsibility on us all to do better. When patients do not participate in their care, do not follow important lifestyle changes, and do not show up for appointments, bad things can happen. And of course medicines do not work if people do not take them correctly.

Years ago, Rosenblatt said, the pharmaceutical industry considered

their contributions to be mainly “chemical” in nature—discovering new medicines and vaccines and getting them approved. But there has been a shift—a true evolution—to a focus on the whole patient, and the whole ecosystem surrounding the patient.

That is where efforts to improve health literacy come in. Research-focused companies like Merck are in a unique position to contribute, as they shepherd discoveries from the lab to the marketplace. It is a journey that involves multiple touchpoints with the patient and with others affecting the patient experience—providers, advocates, payers, and policy makers. Each touchpoint is an opportunity for education and greater understanding.

Unfortunately, many patients have a fundamental distrust of medicine, Rosenblatt said. They might be concerned because the medicine is a chemical, or because it was made by a for-profit company. One of the things the industry can do to build trust is spread the message about medications to help people better understand where a medicine comes from and that the industry does not work in a vacuum. Rather, there is extensive research and clinical trials behind medicines and rigorous evaluations by health authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. If people understand all this better, they might have fewer inner struggles, and more confidence in their medicines. And, said Rosenblatt, trust levels would go up considerably if patients also had an understanding not only of why they need to take a medicine for a particular disease but also about the risks of their medical condition alone.

Rosenblatt highlighted where Merck is on its journey to embed health literacy into its work across many aspects of its business. He said that while creating understanding about diseases and its medicines in patient prescribing information and medication guides is not new, the company has been helping advance health literacy through more formal initiatives in three main areas: advancing the understanding of health literacy as a discipline, including research and its communication; developing and applying health literacy principles in disease education and related materials; and developing tools and services for patients, health care providers, and the broader environment, such as online resources and speaker programs.

Rosenblatt added that health literacy principles enable all to help patients better understand and weigh their choices—not only the risk–benefit of medicines but also the risk–risk ratio—as well as the possible risk of letting the disease take its natural course versus the possible risks of treatment. There is the risk of the disease, the natural history of the disease, and the events associated with that disease. Then there is the risk of side effects of the medicine. If the balance among these factors is not in favor of the medicine, then the patient should not be taking the medicine, Rosenblatt said. But for many people, the concept of benefit means some-

thing else; it means that something wonderful is going to happen when they take the medicine. That is not always the case, he said. It is usually that the patient will not get some sequelae of the disease.

He said the industry can work to apply health literacy principles and standards to efforts ranging from clinical trial recruitment to the packaging of medicines. By increasing the development of expertise in this relatively new area of health literacy, there is the chance to improve patients’ understanding at even more points along their health journeys.

There are many avenues to take in addressing issues of health literacy. In the end, there is probably no “one-size-fits-all” approach. There will be a menu of opportunities, a menu of ways to communicate with different patients, Rosenblatt said. Certain things will work for some but not for others. And it is important to realize that there is no average patient.

Rosenblatt said that the workshop under way has the potential to be a turning point in the field. It can have great impact for patients and can elevate things to the point that health care policy has health literacy as a priority. Merck shares the goals of elevating patient health through patient literacy, he said, and his colleagues at Merck are fully committed to this field.

The floor was opened for discussion. One participant addressed his question to Sørensen, saying that the European survey data show there is a social distribution of health literacy in the population: that is, those who are wealthy and better educated have higher levels of health literacy compared to those who are more disadvantaged. Also, he said, the data show that level of health literacy is related to perceived health. The participant asked if an analysis will be conducted of whether or not health literacy acts as some kind of mediator that might help those who come from more socially disadvantaged backgrounds—that it might protect them somewhat in relation to their health. If it were identified that those having higher health literacy, even when poor, experienced a protective effect on their health, that would be a profound finding on a population basis, he said.

Sørensen said this was something that is beginning to be looked at. The data do show a strong social gradient, and there are additional burdens related to age, low education, or social deprivation. Pelikan also responded to the question and said the analysis is examining the distribution of health literacy across the population and looking at determinants of health literacy. Health literacy is not a dichotomous concept, he said; rather, it is a more-or-less concept, and the data from the survey show very interesting social gradients. The data also show that health literacy

has consequences for some health behaviors, especially for physical activity, which has a positive correlation. There are also correlations with body mass index. But the evidence concerning alcohol use and smoking is very different in different countries. Another finding is that health literacy is second only to age as an important predictor for health. There is also an interesting relationship between health literacy and use of health care services, that is, people with higher health literacy have less use of health care services than people with low health literacy. That, Pelikan said, is a very interesting finding and has implications for costs.

Elena Rios, president of the National Hispanic Medical Association in the United States, addressed her question to Apfel. In the United States, she said, there has been a rise in ethnic media, not just Hispanic but also Asian and African American media, including television, newspapers, and magazines. How, she asked, can one measure the impact of ethnic media as well as how it interconnects with mainstream media at the national level? Apfel responded that this is a tough question. One component relates to how populations are segmented; another relates to how to develop audience-centered communication strategies that address the needs of the users. At the core is finding out where those you want to reach are getting their information, he said.

Apfel said that a recent study on immunization programs had, as a major focus, the Roma populations because there is concern that these populations are either not immunized or underimmunized. In many instances, they were labeled as hard-to-reach populations. Information obtained from talking with people from these populations, conducting focus groups, and examining people’s perceptions and behaviors around vaccination, resulted in an understanding that the Roma populations are poorly reached because of the current system for providing immunizations and information about immunizations.

Apfel said that his organization conducts media audits that examine who the spokespeople are. Those are the individuals one wants to involve in planning whatever effort is under way because the influence of the local media is very important, he said. Local spokespeople also need to be involved in the implementation and evaluation of the program. People from the community one is trying to reach are critical to the effort, he said.

Sabrina Kurtz-Rossi asked Sørensen if she could explain a bit more about the survey and how to access it since it is something that might benefit from the involvement of a wider group of participants. Sørensen said that there is the potential to work much more closely with a broader group. At this stage, the project is sharing results and discussing tools to use to measure policy frameworks and activity plans, and how to develop curriculums. The question is one of how to involve a broader group. She said she talked with Professor Jeanne Rollins from South Bank University

in London to see if it might be possible to establish a federation of health literacy networks. Questions to consider, she said, include how formal such a federation should be; what kind of networks should be involved, or should it be an organization that individuals could join; should it focus on policy, practice, research, or all three; should membership be free, should membership cost something, or is there another way to fund the effort; and what should be the goals of the organization. Apfel said that he hoped a certain kind of credential would not be needed to become involved in health literacy, and that a network seems like a great way to expand and develop a global consciousness.

Isham pointed out that the IOM Roundtable on Health Literacy does not have any requirement for credentials for members, sponsors, or participants in its meetings. Furthermore, the Roundtable appreciates the opportunity to draw upon the expertise of the field, and the strength of the dialogue comes from the mix of backgrounds and people joining together in the conversation.

Jennifer Cabe addressed her remarks to Isaac and Rosenblatt. She said that Isaac talked about Johnson & Johnson engaging with employees to try to improve health outcomes, and that Rosenblatt talked about employees’ interest in health literacy and how that is influencing Merck’s thinking. She asked how employees influence internal policy. Isaac said that part of the engagement and participation strategy has to do with the entry point, which is the health risk assessment process that includes an online survey and response to a number of questions about modifiable risk factors and behaviors. The initial way employees were engaged was by offering a $500 discount on their health or medical contribution. Over the past 17 years’ use of this process, participation rates went from 26 percent in 1993–1994 to a current participation rate of 80–85 percent and a rate of 90 percent satisfaction with the process. The company also has health targets, as discussed earlier. Promotional materials are placed everywhere—from the cafeterias to bulletin boards to restrooms. Representatives from the employee population are asked what they like and what they do not like about various programs. For example, employees who smoke were involved in putting a tobacco-free policy in place. An annual survey is conducted to determine employee attitudes about whether Johnson & Johnson cares about employee health and well-being. Results of that survey vary from company to company and reflect company leadership. These results help identify where additional effort is needed.

Sørensen said that the European Health Literacy Project, in a joint venture on health literacy with Corporate Social Responsibility Europe, conducted a scan to determine to what degree various companies are involved in health literacy. The results showed that Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Nestlé were in the forefront. They have moved health literacy

from the fitness room to the boardroom, she said. What messages do these companies have to take to the other companies that do not have a health-related product, she asked.

Once resources are available, a participant said, employees take more and more advantage of them, and the early indicators are that they are having an impact. Corporations need to understand the link between good health as well as the impact of caring and engagement on people’s happiness and productivity in the workplace. In the United States, most of the message is centered around health care. When discussions are held with senior management, health care cost is emphasized. However, when one travels outside the United States, what is discussed is engagement, using health programs as a method for recruitment and retention, especially in emerging markets.

Rima Rudd congratulated Sørensen and Pelikan for the efforts and findings of the European survey. Can these findings be replicated? Can the same insights and the same findings emerge from different methods and different perspectives? Answering her own question, Rudd said that the answer is an enthusiastic yes because different measures of the health literacy of populations in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the Netherlands came to the same conclusions. Literacy may not be a mediating factor, but it could well be a social determinant of health, she said. That question has not yet been answered. Is a respondent in the survey saying he or she does not have access to needed information because of his or her own lack of skills or because the information is so poorly constructed that it is not accessible? The answer to that question has profound implications for action, Rudd said. Perhaps one needs to focus on the demand side of the equation—improving information, the accessibility of information, and on communication.

Sørensen responded that it is important not to focus on blaming the individual. But the shocking thing is that only 47 percent of individuals are doing well in terms of health literacy. Change must occur, but where that change should start has yet to be determined, she said. It is important to use the results of the comparative study to look at what are the best practices in different systems. Who can we learn from? What is the best approach for different situations?

Isham asked what the impact has been on the countries that participated in the survey in terms of engagement of those in policy and leadership positions. Sørensen said that a network at the European level is being created that will share practices and policies. Activity has varied from country to county, however. Within each participating country there is a national advisory board. Those boards are very different from country to country. In Ireland, for example, they have created the health literacy award, which serves as an example for other countries. In the

Netherlands, there is also an active group of researchers that is developing a health literacy alliance that already has 60 organizations engaged. For Bulgaria and Poland, however, there has been no established activity. In Austria, the results were quickly taken up, and health targets are being established.

Joan Kelly said that it might be useful to look at the Worldwide Wellness Alliance at the World Economic Forum. This alliance brought together 60 multinational companies to begin to share data and information on what works in worksite wellness programs.

Apfel, F. 2012. Health literacy communications. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.

Henke, R. M., R. Z. Goetzel, J. McHugh, and F. Isaac. 2011. Recent experience in health promotion at Johnson & Johnson: Lower health spending, strong return on investment. Health Affairs 30(3):490-499.

HLS-EU Consortium. 2012. Comparative report of health literacy in eight EU member states. The European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU). Available at www.health-literacy.eu (accessed March 26, 2013).

International Telecommunication Union. 2010. Measuring the information society. Geneva, Switzerland: International Telecommunication Union.

Levin-Zamir, D. 2012. Health literacy in Israel: Policy, action, research and beyond. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.

Nutbeam, D. 1998. Health promotion glossary. Health Promotion International 13(4):349-364.

Ratzan, S. C., and R. M. Parker. 2000. Introduction. In National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy, edited by C. Selden, M. Zorn, S. C. Ratzan, and R. M. Parker. NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.

Renders, C. M., G. D. Valk, S. J. Griffin, E. H. Wagner, J. T. Van Eijk, and W. J. Assendelft. 2001. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes in primary care, outpatient, and community settings: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 24:1821-1833.

Sørensen, K. 2012. The European Health Literacy Survey. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World, New York, September 24.

Sørensen, K., S. Van den Broucke, J. Fullam, G. Doyle, J. Pelikan, Z. Slonska, H. Brand, and Consortium Health Literacy Project European. 2012. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 12(1):80.