Since 1993, a great deal of attention has been focused on policy, practice, and program initiatives aimed at improving both the delivery of child welfare services and the outcomes for children who come in contact with the public child welfare system—the system that implements, funds, or arranges for many of the programs and services provided when child abuse and neglect is suspected or has actually occurred. As described by Sanders (2012) at a workshop held for this study and elucidated by the discussion of research needs in Chapter 6, there is a need for further study of systemic factors that impact the response to child abuse and neglect. In keeping with the committee’s statement of task, this chapter considers system-level issues and legislative, practice, and policy reforms as context for the discussion of interventions and evidence-based practices and of their implementation and dissemination in the following chapter. An understanding of these issues can illuminate what happens to children after their risk for child abuse and neglect has been determined, including dispositions and outcomes for children and families, as well as how the system that serves them functions. The chapter begins with an overview of the child welfare system. Following this overview, examined in turn are major policy shifts in child welfare since the 1993 National Research Council (NRC) report was issued, research on key policy and practice reforms, and issues that remain to be addressed. The final section presents conclusions.

OVERVIEW OF THE CHILD WELFARE SYSTEM

Public child welfare agencies provide four main sets of services—child protection investigation, family-centered services and supports, foster care, and adoption. Child welfare agencies need to have some availability 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to respond to child abuse and neglect reports. They are also expected to meet the needs of diverse populations that come to their attention, despite the families’ different histories, needs, resources, cultures, and expectations (McCroskey and Meezan, 1998).

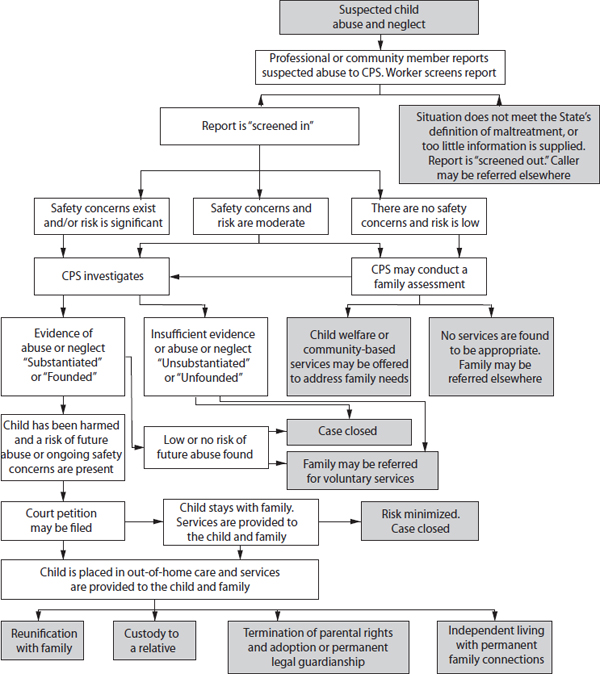

For situations involving child abuse and neglect, children come into contact with the designated state or local (county-based) child welfare agency when a call is made to report child abuse and neglect, and the child protective services agency decides whether to accept the report and investigate it, and then decides on a course of action related to the outcome of that investigation.

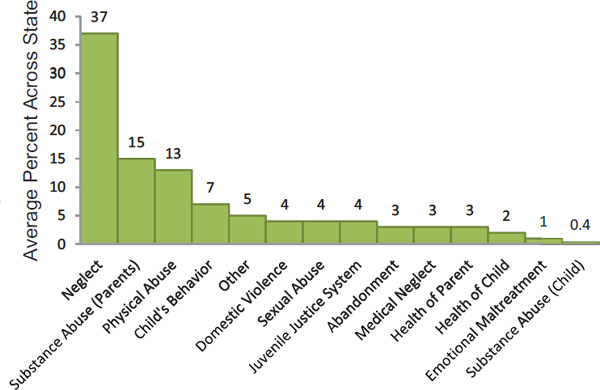

Children found to be abused or neglected may remain in their own home, but those assessed as not being safe in their own home are placed in out-of-home care. Initially, such care is almost always considered to be temporary, providing an opportunity for change in the behavior, social supports, and living environment of the parents and/or the children’s behavior or health status such that is safe to reunify the children with their families. According to data from the 2007-2008 round of Child and Family Service Reviews, which cover 32 states, reasons for a child welfare agency’s opening a case were neglect (37 percent), parental substance abuse (15 percent), physical abuse (13 percent), child’s behavior (7 percent), other (5 percent), domestic violence (4 percent), sexual abuse (4 percent), juvenile justice system (4 percent), abandonment (3 percent), medical neglect (3 percent), health of parent (3 percent), health of child (2 percent), emotional maltreatment (1 percent), and substance abuse of the child (0.4 percent) (ACF, 2012b) (see Figure 5-1). Figure 5-2 depicts a child’s journey through the child welfare system, while Box 5-1 describes the child welfare system for American Indian children.

Scope of Child Welfare Placement

Each year, more than 3 million referrals for child abuse and neglect are received (3.4 million in 2011) that involve around 6 million individual children (6.2 million in 2011) (ACF, 2012c). In 1998, 560,000 children were in foster care (ACF, 2000). By September 30, 2011, the number of children in foster care had declined to 400,540 (ACF, 2012a). Approximately 3 of 5 referrals to child protective services agencies are screened in for investigation or assessment, and from 1 in 4 to 1 in 5 (25.2 percent in 2007, 20.0 percent in 2011) of these investigations lead to a finding that

FIGURE 5-1 Case-level data: Primary reason for case opening in 32 states.

SOURCE: ACF, 2012b.

at least one child was a victim of child abuse or neglect, resulting in an estimated number of 794,000 unique child victims in 2007 and 681,000 in 2011 (ACF, 2007, 2012c). Neglect is by far the major type of maltreatment, with more than four-fifths (78.5 percent) of victims being neglected in 2011, while 17.6 percent were physically abused and 9.1 percent were sexually abused (ACF, 2012c).

Although the public perception may be that most substantiated child abuse and neglect reports result in placement of the child in out-of-home care (and perhaps siblings as well, who may or may not have been abused), this is not in fact the case. The number of child victims (and child nonvictims) placed in foster care represents a relatively small percentage of substantiated reports and can best be estimated from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW). In the first NSCAW cohort, 82.3 percent of the children remained in their home after investigation (Horwitz et al., 2011) (compared with 79.3 percent based on federal data in 2007 [ACF, 2007]).

Whether any given abused or neglected child is placed in foster care varies substantially. Children under 1 year old are most likely to be placed (ACF, 2012a). Among black children in this age group, the risk of placement is particularly high. Once children are in foster care, placement trajectories

FIGURE 5-2 A child’s journey through the child welfare system.

SOURCE: CWIG, 2013b, p. 9.

vary considerably. Although group and other forms of congregate care have been linked to negative developmental sequelae (Barth, 2005; Berger et al., 2009), 22 percent of all children and 48 percent of all teenagers are placed in some type of group facility upon admission to out-of-home care.

Caregiver changes, which also are associated with negative developmental sequelae (Aarons et al., 2010; Barth et al., 2007; Newton et al., 2000), affect more than half of all children who are placed, with roughly 30 percent of foster children experiencing three or more placements (Landsverk

BOX 5-1

The Child Welfare System for American Indian Children

A child abuse and neglect report relating to an American Indian child may be investigated by the child’s tribe, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or a state or county agency (Cross, 2012; see also CWIG, 2012b). Child abuse and neglect reports may also be investigated by multiple actors, with tribes being involved in 65 percent of investigations (23 percent as sole investigators), states in 42 percent, counties in 21 percent, the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 19 percent, and a consortium of tribes in 9 percent (Earle, 2000).

The aim of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA),* which was passed in 1978, is to preserve tribal authority over decisions to place American Indian children in out-of-home care. According to the ICWA, tribes with active courts maintain exclusive jurisdiction for American Indian children residing on the reservation, and states and tribes share jurisdiction for children who do not live on reservations but are members of federally recognized tribes or are eligible for tribal membership with a biological parent who is a tribal member. State courts conducting involuntary child welfare proceedings concerning children subject to the ICWA must notify the appropriate tribe, which has the right to intervene in the case. The ICWA requires that American Indian children placed in foster care be placed close to home, with preference for placement with a member of the child’s extended family; a foster home licensed, approved, or specified by the tribe; an American Indian foster home licensed or approved by a nontribal authority; or an institution approved by the tribe. American Indian children placed for adoption should be placed with a member of the child’s extended family, a member of the child’s tribe, or another American Indian family.

________________

*P.L. 95-068.

and Wulczyn, 2013). About 60 percent of all placed children are reunified with their family; 20 percent are adopted; and the remainder leave for other reasons, including aging out (6 percent). Frequently unaccounted for, however, is the significant variation among and within states with respect to how long children remain in foster care. The median length of stay ranges from 5 to 24 months at the state level and from 2 to 35 months at the county level. Finally, about 1 in 5 children will return to care within 2 years of exit; for some populations, the reentry rate is as high as 35 percent (Wulczyn et al., 2007, 2011).

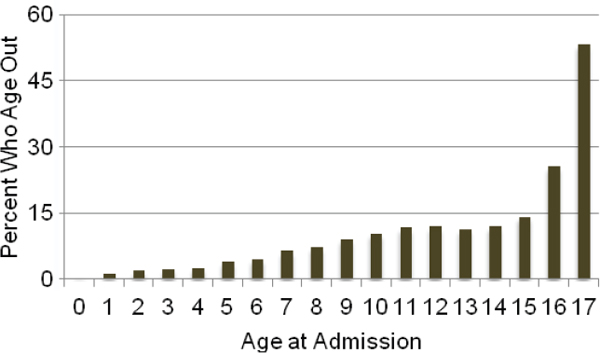

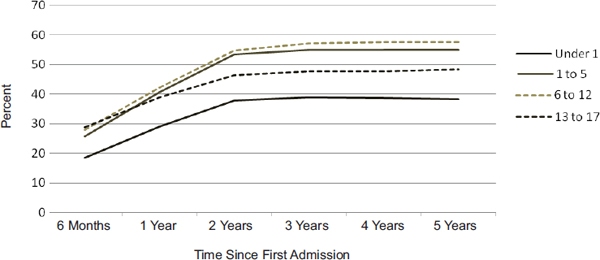

Aging out of foster care is strongly related to age at entry, as shown in Figure 5-3. Infants are the least likely to age out. Based on the Multistate Foster Care Data Archive (FCDA), fewer than 25 of 2,500 infants (less than 1 percent) remained in placement for their entire childhood. At the other end of the age continuum, about 50 percent of 17-year-olds aged out

FIGURE 5-3 Probability of aging out of foster care by age at admission.

SOURCE: Data from Wulczyn, 2012.

directly from foster care. Between these two extremes, less than 15 percent of any single age group aged out, except for 16-year-olds.

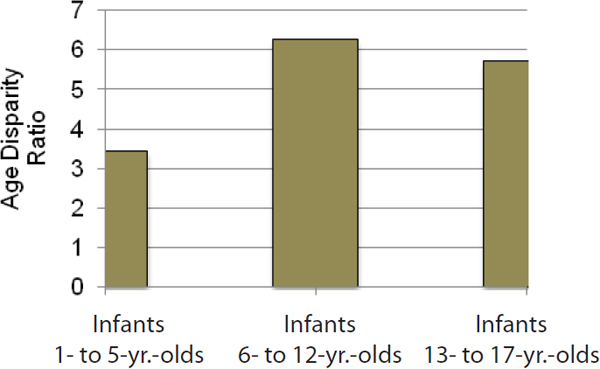

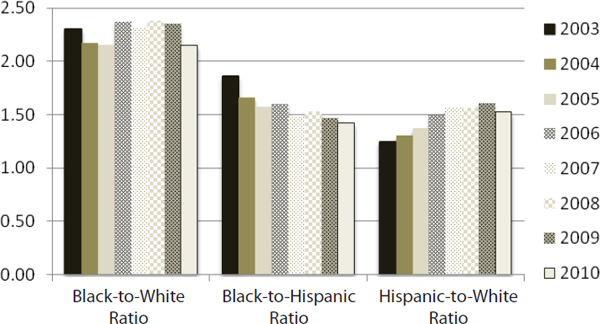

As noted, the youngest children, particularly those under the age of 1 year, have the greatest risk of placement. For that age group, placement rates were never below 10 per 1,000 and reached 12 per 1,000 in 2006. Among children aged 6 and above, the incidence of placement hovered close to 2 per 1,000, also with a peak in 2006.

The stark age-graded disparity in placement rates is seen clearly in Figure 5-4. The height of these bars depicts the magnitude of the difference in placement rates for infants relative to three other age groups. Compared with 1- to 5-year-olds, infants are about 3.5 times more likely to be placed. The disparity between infant placement rates and the rates for 6- to 12-year-olds averaged 6 placements per 1,000 between 2003 and 2010.

Type of Placement

Because of how much time foster children spend in living arrangements other than those provided by their parents, the settings in which they are placed make a difference. In general, states offer three main types of placement. Family-based care, which is preferred, consists of regular foster family care and relative (kinship) care. Children placed in family foster care may live with other foster children, but the number of unrelated foster children allowed in the home is regulated. More important, the foster parents are in

FIGURE 5-4 Age disparity ratios for infants relative to children of other ages.

SOURCE: Data from Wulczyn, 2012.

most cases psychological strangers to the child. Relative foster care involves foster parents who are related to the child either biologically or through fictive kin relationships. Over the past 15 years, kinship care has become the preferred practice option, and its use has increased as a result. The last general placement type is group care. States support a wide variety of group or congregate care settings, from smaller group homes with, for example, six unrelated youth residents to larger campus-based residential treatment facilities. States vary considerably in the range of group care settings, with some states using classification systems that differentiate 10 or more group-based settings depending on the level of care needed.

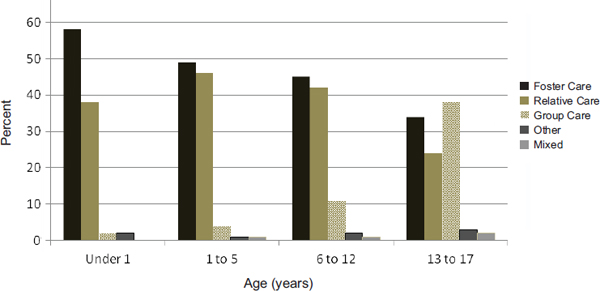

The data in Figure 5-5 show, by age at admission, how children spent the majority of their time with regard to placement setting in 2003 and 2010. “Predominant placement setting” refers to the setting where children spent more than half their time in foster care. The mixed care type refers to situations in which no one placement type accounted for more than half the time spent in care. The overwhelming majority of children under the age of 13 spent most of their time in placement in a family setting. Nearly 96 percent of infants admitted between 2003 and 2010 spent the majority of their time in a family setting. For older children, group care was the most common care type, with about 38 percent of adolescents spending the majority of their time in foster care in some type of group care setting.

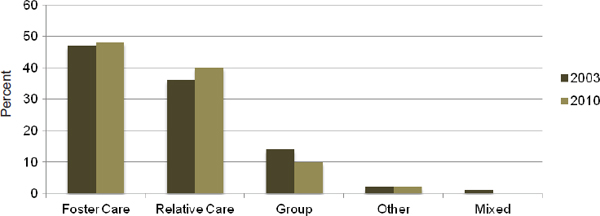

Data also suggest that the use of family-based care is on the rise. As shown in Figure 5-6, the data suggest that the use of both regular and

FIGURE 5-5 Predominant placement type.

SOURCE: Data from Wulczyn, 2012.

kinship foster care increased between 2003 and 2010, whereas the use of group care declined.

The deleterious impact on children of multiple placements in foster care has been a salient topic in child welfare policy and programmatic debates for decades. Legislative initiatives to promote permanency for foster children (e.g., the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act, the Adoption and Safe Families Act) have led to increased emphasis on greater placement stability. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) now monitors the number of movements recorded for children in foster care as part of the national outcomes standards (ACF, 2002).

Although stable placements are preferred, children do move between

FIGURE 5-6 Change in predominant placement settings, 2003-2010.

SOURCE: Data from Wulczyn, 2012.

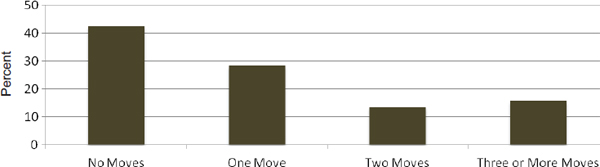

FIGURE 5-7 Average number of moves per child, 2003-2010.

SOURCE: Data from Wulczyn, 2012.

placement settings (see Figure 5-7). Grouped by how many moves they experienced, the largest group of children (43 percent) experienced but one placement (i.e., no moves). About 28 percent of children experienced two placements, while 30 percent experienced three or more placements.

The clinical literature documents the negative effects of placement instability on children. Multiple placements are alleged to affect children’s attachment to primary caregivers, an important early developmental milestone (e.g., Fahlberg, 1991; Lieberman, 1987; Provence, 1989; Stovall and Dozier, 1998). Empirical evidence from other strands of research suggests that multiple placements lead to psychopathology and other problematic outcomes in children, such as externalizing behavior problems (Kurtz et al., 1993; Newton et al., 2000; Widom, 1991).

Despite what is known about the likely impact of placement moves, relatively little research exists on placement stability. An early review of that literature (Proch and Taber, 1985) indicates that the majority of foster children do not experience more than two placements while in foster care. The limited subsequent research focuses on placement disruption rates and factors associated with movement. Generally, researchers report that between one-third and two-thirds of traditional foster care placements are disrupted within the first 1-2 years (e.g., Berrick et al., 1998; Palmer, 1996; Staff and Fein, 1995). Research on treatment foster care has documented a wider range for rates of disruption, from 17 to 70 percent (Redding et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2001; Staff and Fein, 1995). Although kinship foster homes tend to be more stable than traditional foster homes (Courtney and Needell, 1997), some evidence suggests that kinship placements also may be disrupted frequently, reflecting the vulnerability of the child and the family (Terling-Watt, 2001). Findings from Cochrane Collaboration systematic review of kinship care for children who have experienced child abuse and neglect (Winokur et al., 2009) suggest that children in kinship foster care experience better behavioral development, mental health functioning, and placement stability

than children in nonkinship foster care. Although no difference in reunification rates was found, children in nonkinship foster care were more likely to be adopted, while children in kinship foster care were more likely to be in guardianship. Children in nonkinship foster care also were more likely to utilize mental health services.

Several studies identify factors associated with placement disruption. Early research by Pardeck and colleagues (Pardeck, 1984, 1985; Pardeck et al., 1985) suggests that such child characteristics as older age and behavioral or emotional problems are associated with increased rates of disruption. These findings are corroborated by more recent research (e.g., Palmer, 1996; Smith et al., 2001; Staff and Fein, 1995; Walsh and Walsh, 1990). Findings concerning the relationship of placement disruption to child race and gender are mixed (Palmer, 1996; Smith et al., 2001).

Another study on placement stability examined the link between turnover among child welfare caseworkers and the achievement of permanence for children in Milwaukee County. The authors found that children who experienced caseworker turnover had more placements (Flower et al., 2005).

Many studies investigate the attributes of children and their circumstances in an effort to explain variation in the number of movements. Relatively little work focuses on the movement patterns themselves, and few studies (James et al., 2004; Usher et al., 1999) examine combinations of moves to understand whether the patterns have meaning for child welfare policy and practice.

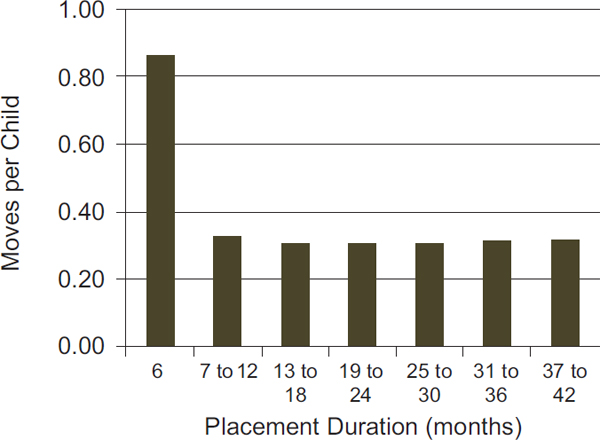

The timing of moves is also important (see Figure 5-8). Movement early in the placement experience may magnify a child’s sense of instability; movement late in the placement experience may signal changes in the child’s status, the caregiver’s capacity, or both. Because movement and length of stay are so closely intertwined, however, care must be taken in isolating when movement is most common.

Although placement stability is desirable, placement changes are sometimes necessary. For example, children placed in a group care setting may transfer to a family setting if the reasons for placement in group care are no longer material to further progress. Similarly, when caseworkers find a willing and able relative, transfer out of foster care to relative care may be in the long-term best interest of the child. Thus, the number of moves is not the only metric by which to judge whether stability has been achieved. Movement between levels of care or up and down the care continuum provides another view of what happens while children are placed away from home.

The data do suggest that changes in the level of care are common. About 60 percent of children who started off in family foster care and were then transferred to a group care setting went on to experience a third placement, which half of the time involved a return to family care.

FIGURE 5-8 Period-specific movement rates, 2003-2010.

SOURCE: Data from Wulczyn, 2012.

Exit from Foster Care

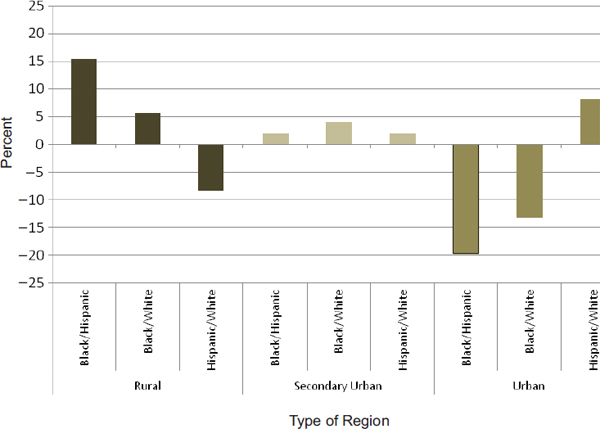

For the past 30 years, child welfare policy and practice have focused on reducing the time spent in foster care. The goal of reduced time in care aligns with the notion that foster care is a temporary alternative to care provided by parents. Figure 5-9 shows the cumulative probability of exit for reunification, by age at first admission to foster care. The cumulative probability indicates the likelihood of exit with the passage of time. Referring to Figure 5-9, for example, about 40 percent of infants placed will have been discharged back to their parents within 5 years. Among 13- to 17-year-olds, the figure is closer to 50 percent; for children between the ages of 1 and 12 at the time of admission, the cumulative probability of reunification falls to between 55 and 60 percent.1

The data in Figure 5-9 also suggest that after 2 years, the cumulative probability does not change dramatically, regardless of the age at admission.

________________

1The cumulative probabilities are based only on those cohorts for which at least 3 years of data are available: 2003, 2004, and 2005. The cumulative probability of reunification within 6 months is based on the experience of the 2003 through 2009 admission cohorts. Thus, for the first interval (i.e., 6 months), seven estimates are averaged together, while for the last interval, only three estimates are available.

FIGURE 5-9 Cumulative probability of reunification by age at first admission to foster care.

SOURCE: Data from Wulczyn, 2012.

In large measure, this pattern is attributable to the fact as the likelihood of reunification drops off, the likelihood of some other exit to permanency increases. The drop-off in reunification after 2 years is compensated for by an increase in exits to relatives and adoptions.

Reentry to Foster Care

Reentry to foster care refers to children who return to placement after having been discharged from foster care. Although reentry to foster care may be preceded by repeated child abuse and neglect, few studies actually follow that sequence of events. From a policy and practice perspective, there are three types of permanency: reunification, guardianship, and adoption. Of those types, reentry to foster care following reunification or guardianship is easy to track with administrative data. Tracking reentry to foster care following adoption is more difficult. When children are adopted, in keeping with the idea that a new family has been formed, states typically establish a new identity for the child, including new client and case identifiers. In the process of creating a new identity, connections between the old and the new are often severed.

Even among children who exit to permanency for reasons unrelated to adoption, following reentry is difficult with respect to the amount of time needed to observe the full extent of the process. For example, some children admitted to foster care will be reunited with their families after 2 years in placement. Among those children, some will return to care, but not for 2 or more years after reunification. When the time segments are added together, it can take more than 5 years to establish the likelihood of reentry.

Although statistical methods are available to address these concerns, those methods do not alleviate completely the time needed to understand the full extent of reentry.

Child Abuse and Neglect in Out-of-Home Care

While the impact of placement on access to ameliorative services is clearly beneficial, as has been robustly shown in the case of access to mental health services, it is also important to consider the potential negative consequences of placement in foster care. This section examines this issue briefly with regard to what is known about child abuse and neglect in foster care. This subject is difficult to address because of the nature of abuse and neglect that occurs while a child is under the official care of the state, the court, and the child welfare system as a result of abuse and neglect suffered in the child’s biological home—a kind of double jeopardy. It is also a difficult subject to examine empirically because there are three quite disparate sources of information to consider: (1) “official” data generated by child welfare systems and reported by states to the federal government through the Child and Family Service Reviews (CFSRs) and the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS); (2) findings from investigative and advocacy organizations, such as newspapers and advocacy groups; and (3) data and findings generated by researchers.

When children are placed in out-of-home care, the state assumes responsibility for their care, including their safety. The Adoption and Safe Families Act2 states that child safety is the primary consideration in determining services, placement, and permanency. The federal CFSRs require that child welfare agencies reduce the incidence of abuse and neglect of children in out-of-home care. In 2010, states reported that abuse and neglect rates for children in foster care ranged from 0.00 to 2.33 percent, with a median of 0.35 percent (ACF, 2010).

There are reasons to believe that this source generates underestimates of the true rate of abuse and neglect experienced by children while in foster care. First, the definition used by the CFSRs—“Of all children who were in foster care during the year, what percentage were the subject of substantiated or indicated maltreatment by a foster parent or facility staff member?” (ACF, 2011)—is very limited. It does not include abuse or neglect by other adults or youth in the home, or abuse and neglect that was experienced by the child while in care but that might have been prevented by actions of the adult caregivers in the home. Second, investigative sources such as newspaper articles offer clear evidence that some child welfare systems, or other agencies designated to respond to such reports, do not thoroughly

________________

2P.L. 105-89.

investigate allegations of abuse or neglect of children in foster care or keep good records of these investigations (Cleveland, 2013; Kaufman and Jones, 2003). Investigative reporting has quite different rules of evidence from those used in formal research studies, and may also be biased toward negative examples (e.g., the most egregious service systems) and fail to consider the full range of child welfare systems. Yet these examples raise serious question about the possible underestimation of child abuse and neglect in foster care, although they do not provide research evidence on the size of this underestimation.

Unfortunately, research on abuse and neglect in out-of-home care is sparse (Benedict et al., 1994; Poertner et al., 1999; Zuravin et al., 1993). Nonetheless, it demonstrates some differences in the type of abuse reported and the substantiation rate for reports as compared with abuse and neglect reports in general. Some studies indicate that reports received while a child is in foster care may pertain to abuse or neglect that occurred prior to entering foster care (Tittle et al., 2001, 2008). Poertner and colleagues (1999) report on the results of a study of a large state public child welfare agency using existing management information systems that found a rate of abuse and neglect in foster care ranging from a low of 1.7 percent to a high of 2.3 percent over a 5-year period. However, this study suffers from the same problems seen in the CFSR reports and does little to resolve the large differences in rates between research-based work and newspaper investigations. The conclusion to be drawn is that this research literature is thin, and a well-designed national study that can address the problem is needed.

Finally, the committee notes that efforts to prevent abuse and neglect in foster care include (1) training and services for foster families and facility staff members; (2) increased interaction among the caseworker, the caregiver, and the youth; and (3) more stringent background check requirements for those who provide foster care. The Child Welfare League of America has established best practice guidelines for how child welfare agencies should prevent abuse and neglect and respond to abuse and neglect reports for youth in foster care (Child Welfare League of America, 2003).

State-to-State Variation

Although federal child welfare policy creates a national context for the operation of foster care programs, it is important to remember that states have considerable leeway as to the form and structure of their local child welfare systems. Most states operate what are called state-supervised, state-administered systems; however, 11 states devolve authority for administering the child welfare system to counties. Almost all states use private foster care providers to some extent; in some localities, all foster care is in the hands of private, nongovernmental agencies. As important, states differ

with respect to the types of child abuse and neglect brought to the public agency’s attention. Thus considerable variation exists among and within states in the use of foster care as a response to child abuse and neglect.

As a result of these many sources of variation in state and local child welfare systems, state-to-state comparisons of children’s experiences in child welfare systems may obscure important and consequential differences in child and case characteristics. Only rarely are data collected to a level of detail sufficient to permit examination of the fate of equivalent cases across states and policies, beyond simple comparisons of cases matched by race and age. With this type of data, analysis using emerging quasiexperimental methods may be able to examine more complex interactions between state and local policies and children’s experiences in child welfare systems.

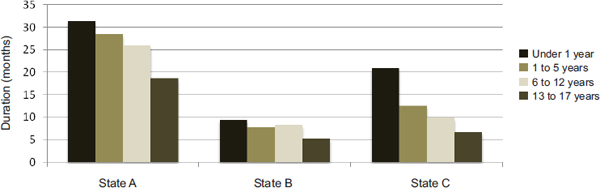

States vary as well in the duration of out-of-home care. Figure 5-10 shows the duration for three states to illustrate the magnitude of the differences. First, it is important to highlight the similarities. In each of these three states, infants remain in care longer than children of other ages; older children (13- to 17-year-olds) remain for the least amount of time. That said, the state differences are stark. In state A, the median duration of care for infants is in excess of 30 months; in state B, the figure for the same group of children is under 10 months; and in state C, the figure is just over 20 months. State variation also is considerable for other indicators—use of group care, placement stability, and reentry.

It should be noted that variability within states is as significant as that among states. To a large extent, states are a reflection of their largest county or counties, and what is true in medium-sized counties can be quite different from what is true in larger counties. Because of the variability among states, one must be careful in drawing inferences about state-level outcomes

FIGURE 5-10 Variation among states in median duration (in months) of first admission to out-of-home care, by age.

SOURCE: Data from Wulczyn, 2012.

from a national picture; likewise, local (e.g., county) outcomes may be quite different from state-level outcomes.

Finally, a note about the possible impact of state differences with respect to their administrative structure (i.e., county- versus state-administered systems) is in order. No published research examines whether state administrative structure is in some way related to the performance of child welfare systems. In an unpublished exploratory study looking at length of stay in foster care, Wulczyn and colleagues (2011) used administrative structure as a model covariate and found no significant relationship between duration of care and administrative structure, given other variables in the model. More to the point, states differ in so many ways—spending on foster care, poverty rates, policy, use of private agencies—that it is difficult to predict whether administrative structure makes a unique contribution to the system’s underlying performance. This is an important area for study given the cost of operating county-administered systems.

Finding: Contrary to popular belief, most investigated reports of child abuse and neglect do not result in out-of-home placement; only about 20 percent of investigated cases result in the removal of a child from his or her home.

Finding: Risk of placement and length of stay in out-of-home care can vary considerably based on such factors as the child’s age and the family’s race, socioeconomic status, and state of residence.

Finding: Significant variation has been found among and within states in the length of time children remain in foster care. However, this variable frequently is omitted in studies on out-of-home placement. Little research has assessed the factors accounting for this variation to support the development of placement, placement prevention, and reunification practices so as to avoid or shorten placements.

Finding: Children placed in kinship foster care have been shown to experience better behavioral development, mental health functioning, and placement stability than children placed in other forms of care, and can achieve permanency through guardianship (as supported by the Guardianship Assistance Program in the Fostering Connections to Success Act of 2008). As a result, evidence suggests that placement with kin has in the last 15 years become an increasingly preferred option for child welfare systems.

Finding: Evidence suggests that placement instability can lead to a variety of negative consequences for children in the child welfare system.

However, relatively little research has been conducted on this issue, especially with regard to the impact of multiple placements, including research on the separate effects of movement patterns, the timing of moves, and movement between levels of care. Further, definitions of placement instability vary across states, and little research has been done to elucidate the meaning of these varying definitions.

Finding: Current research is inadequate to permit an accurate assessment of rates of reentry into foster care, particularly with regard to tracking reentry after adoption and following children longitudinally for a length of time sufficient to observe the full extent of reentry.

Finding: The experiences of children involved in the child welfare system vary considerably among and within states. These variations are due largely to differences in the form and structure of states’ local child welfare systems, as well as differences in how child abuse and neglect are defined, reported, and responded to by public agencies. Research is insufficient to determine whether differences in state administrative structures (county- versus state-administered systems, extent of privatization) relate to the performance of child welfare systems.

MAJOR POLICY SHIFTS IN CHILD WELFARE SINCE 1993

Public child welfare services occur in the context of the prescribed federal child welfare outcomes of safety, permanency, and well-being that were codified in the Adoption and Safe Families Act. The three principal outcomes—safety (being safe from further child abuse and neglect), permanency (stability when in child welfare care and achieving permanency through reunification, adoption, or guardianship), and well-being (often characterized as child well-being, focused primarily on physical health; behavioral, emotional, and social functioning; and education)—frame the mission for child welfare services in response to child abuse and neglect. Historically, child welfare agencies have focused on the first two outcomes as their primary mandate and the areas in which they have clear expertise. They have been ambivalent about fully embracing the third element because the expertise for providing both preventive and ameliorative services targeting child well-being usually resides in other child-serving systems, such as child physical and mental health, developmental, and educational services. Nonetheless, child welfare policy, practice, and research recently have demonstrated a more robust focus on child well-being, as indicated by both the title of the landmark national child welfare study National Survey on Child and Adolescent Well-Being and multiple initiatives from the Administration

on Children, Youth and Families (ACYF) under the leadership of Commissioner Bryan Samuels since 2009.

Child welfare services also are intended to embrace a “systems of care” perspective that federal child welfare oversight has recommended for adoption by state and local agencies (Children’s Bureau, 2012). Systems of care, drawn from wraparound services in the children’s mental health field, is a service delivery approach intended to build partnerships for creating an integrated process that can meet families’ multiple needs. It is based on principles of interagency collaboration; individualized, strengths-based care practices; cultural competence; community-based services; accountability; and full participation and partnerships with families and youth at all levels of the system. To be effective, systems of care need to build an infrastructure that will result in positive outcomes for children, youth, and families (CWIG, 2008).

Since 1993, child welfare systems have undergone a number of changes in policy, service delivery, and system design so as to better meet safety, permanency, and well-being goals. Some of these changes are due to the implementation of new federal3 and state legislation (see Chapter 8) and to replications of innovative program models (see Chapter 6) that have been widely disseminated after garnering some positive program evaluations.

Improvements and service changes also have occurred as a result of efforts to address service gaps identified in class action lawsuits, frequently filed by national entities such as Children’s Rights or the Youth Law Center, or in response to deficiencies identified in the federal CFSRs that assess states’ delivery of child welfare services. These changes have signaled the desire to implement programs and services that better target the needs of children in their own homes, that address service and decision-making disparities that result in the overrepresentation of children of color in the child welfare system, and that address strategies for engaging families more effectively and actively in the development of their own plan of services. The focus of child welfare services may also change after a horrific and highly visible death due to child abuse and neglect—sometimes causing the decision-making pendulum to swing toward placing children in out-of-home care, while at another point in time the same assessment might have resulted in a child’s staying with his or her family.

Numerous policy and programmatic initiatives have been designed to keep children from entering the child welfare service system (e.g., differential or alternative response—see the discussion on p. 198); to keep children from being placed in out-of-home care (family-based interventions such as family preservation services and family group conference decision making); to place children with kin (e.g., subsidized guardianship and increased at-

________________

3For example, see P.L. 103-66, P.L. 105-89, and P.L. 110-351.

tention to finding relatives that might become placement options); and to move children on to more permanent placement more quickly through family reunification, subsidized guardianship with kin, or adoption. Expedited time frames for permanency were made more explicit through the imposition of placement time limits designed to achieve permanency once a child has entered out-of-home care, along with incentives to states to increase adoptions, under the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997.4 During the 20-year period since the 1993 NRC report was issued, increased attention has been focused on the development of decision-making tools for assessing immediate risk, safety, and family and child functioning to support the formulation of a plan of care (see the discussion of risk, safety, and needs assessment later in this chapter).

To understand the outcomes of abused and neglected children in the child welfare system, it is important to understand the legislative and system-level reforms that drive child welfare services. The key reforms are described in the following subsections.

Legislative Reforms

Legislative reforms driving child welfare services include provisions for family preservation and family support programs, the Adoption and Safe Families Act, the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act, the Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act, and Title IV-E waivers.

Family Preservation and Family Support

The release of the 1993 NRC report occurred close to the passage of the Family Preservation and Family Support provisions of P.L. 103-66, amending the Social Security Act to create Title IV-B Part 2. The hope was that states would use these new funds to focus on prevention through community-based family support programs designed to strengthen and stabilize families through parent training, drop-in centers and early screening, and family preservation programs targeting families at risk or in crisis, thus helping to keep children out of out-of-home care and to support more timely reunification.

Not only was this funding very limited, however, but as with many child welfare services, states varied widely in how they carried out these efforts, how the funds were allocated across the state, whether specific program models (e.g., Homebuilders) were implemented, and which particular populations were targeted (e.g., urban/rural, older/younger, preplacement

________________

4P.L. 105-89.

interventions/reunification). The 1993 legislation required the Secretary of HHS to evaluate the effectiveness of Family Preservation and Family Support Programs, which would also help better identify the evidence base for these efforts. But variations in implementation made evaluation difficult, and the federal evaluations were equivocal, especially with respect to outcomes of foster care placement (ASPE, 2008a).

Although attention to programs specifically called Family Preservation and Family Support has waned, a commitment to working together with families in their own homes and assisting with parenting and other interventions has continued, using different terms and program names (see below and Chapter 6).

Adoption and Safe Families Act

Enacted in 1997, the Adoption and Safe Families Act5 reauthorized the Family Preservation and Family Support Programs, retitled Safe and Stable Families; codified the expectations of child welfare outcomes related to safety, permanency, and well-being; and required that safety be assessed at every decision point in case planning and judicial review. The legislation also emphasized the role of substance abuse in child abuse and neglect, stressed children’s health and safety and clarified “reasonable efforts” emphasizing children’s health and safety, and required states to specify situations in which services to prevent foster care placement and reunification are not required. The Adoption and Safe Families Act also set specific timelines for making decisions about permanent placement, requiring that states initiate termination of parental rights after a child has been in foster care for 15 of the previous 22 months. When parental rights are terminated, the parents no longer have a legal relationship with their child, allowing the child to be placed for adoption (CWIG, 2013a). States also became eligible for bonuses for increasing the number of children adopted. HHS was required to establish new outcome measures with which to monitor and improve states’ performance, which resulted in creation of the CFSRs. Finally, the act reauthorized the option of using child welfare funding more flexibility through Title IV-E waivers (discussed below), first created in 1994.

Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act

Enacted in 2008, the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act6 amended Title IV-E and Title IV-B of the Social Security Act

________________

5P.L. 105-89.

6P.L. 110-351.

to connect and support relative caregivers, improve outcomes for children in foster care, provide for tribal foster care and adoption access, improve incentives for adoption, and extend Medicaid eligibility to children in kinship guardian assistance settings. The act also required agencies to find relatives and make greater efforts to keep siblings together, and sought to ensure better coordination among education, health, dental, mental health, and child welfare services. In addition, Title IV-E assistance was extended to older youth who are in care by age 16, and the development of a youth-directed transition plan for such cases was encouraged. The act also emphasized connection to families for children in foster care or at risk of placement by providing states with grants to find families, support kinship placements through subsidized guardianship, and support family group conferencing and kinship navigators so that youth could remain more connected to family and perhaps find family with whom to stay.

Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act of 20117

This legislation reauthorized the Safe and Stable Families Program and further amended Title IV-B by focusing on the well-being of children, addressing the emotional trauma of children who experience the child welfare system, providing special attention to the needs of young children (under 5), and requiring states to monitor the use of psychotropic medications for children in foster care. This legislation also reauthorized the availability of Title IV-E waivers (see below) through 2014.

Title IV-E Waivers

Title IV-E waivers, first authorized in 1994 under P.L. 103-432 and reauthorized under the Adoption and Safe Families Act, expired in 2006, but were reauthorized again in 2011 under the Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act (described above). They allow states to waive certain Title IV-B and Title IV-E requirements that govern foster care, adoption, kinship guardianship assistance, and other programs to create demonstration programs that are cost neutral. States can redistribute the use of funding to keep children from entering out-of-home care and to offer and access more comprehensive services. Between fiscal year (FY) 1994 and FY 2006, 23 states implemented one or more waivers to target service strategies including subsidized guardianship and kinship permanence, flexible funding to local child welfare agencies, managed care systems, services for caregivers with substance abuse disorders, intensive services including expedited reunification, and adoption and postpermanency services (Patel

________________

7P.L. 112-34.

et al., 2012). These initiatives required extensive evaluations, several of which used random assignment in experimental designs (Testa, 2010), and the findings from these programs helped set the stage for the reauthorization of both the authority and provisions related to kinship guardianship assistance that were included in the Fostering Connections Act.

The new 2011 waiver authority, which enables the secretary of HHS to authorize up to 10 demonstration projects each year during FY 2012-2014, has more explicit goals than the previous waiver programs, including increasing permanency for youth; reducing time in foster care; promoting positive outcomes for children, youth, and families in their homes; and preventing child abuse and neglect and the reentry of infants, children, and youth into foster care. The legislation also contains a stipulation that the federal waiver application review cannot consider whether the waiver will use an experimental design for the application, an interesting turn since many view the use of random assignment in the earlier waivers as a positive process (Testa, 2012). The new waiver authority specifies that funds can be used to establish programs designed to provide permanency and prevent children from entering foster care. These programs include intensive family finding, kinship navigator, and family counseling programs; comprehensive family-based substance abuse treatment; programs designed to identify and address domestic violence; and youth mentoring programs. The new waiver authority also establishes as priorities the production of positive well-being outcomes, with attention to addressing trauma; enhancement of the social and emotional well-being of children and youth; contributions to the evidence base for improving the lives of children and families; and leveraging of the involvement of other resources and partners. In FY 2012, the Children’s Bureau funded nine new waivers. (Summaries of these new programs can be found at http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/programs/child-welfare-waivers#summaries [accessed March 6, 2014].) It will be important to continue to follow these efforts, especially with regard to the intent to reduce child abuse and neglect and implement evidence-based programs.

SYSTEM-LEVEL REFORMS INTENDED TO

IMPROVE PRACTICE AND OUTCOMES

Beyond specific federal legislation that has paved the way for practice reforms, states and localities have adopted a number of system-level reforms most likely intended to improve child and family outcomes.

Safety, Risk, and Needs Assessment

Assessment in child welfare involves at least three distinct processes: safety assessment, in which the social worker determines whether a child

is currently safe in his or her home or out-of-home placement; risk assessment, in which the social worker assesses the likelihood that the child will experience a recurrence of abuse and neglect in the future; and needs assessment of child and family functioning, which is used to develop case plans. Assessment may occur at multiple points during the child’s engagement with the child welfare system, including determination of the response to an initial report of abuse or neglect, placement decisions, and case closure (D’andrade et al., 2008).

All three types of assessment are critical decision aids designed to complement case workers’ clinical judgment in determining the best course of action for each child and case. Two approaches to assessment have been pursued within the field of child abuse and neglect: actuarial, which has been used to determine risk, and consensus-based, which has been used to determine safety, risk, and needs. Actuarial risk instruments use statistical methods to calculate the probability that a child will experience a recurrence of abuse or neglect in the future, based on risk factors identified with recurrence of abuse and neglect in the empirical literature. Consensus-based instruments are created based on theories of child abuse and neglect etiology, empirical research, and expert opinion on relevant case characteristics.

Actuarial risk assessment instruments clearly have the greatest potential to estimate the recurrence of child abuse and neglect reliably and accurately, and child welfare agencies in the majority of U.S. states use such tools (Coohey et al., 2013; Schwalbe, 2008). This type of risk assessment, however, does not indicate which clinical factors are most important to address and certainly does not indicate which services are most likely to be effective. The Structured Decision Making (SDM)© approach is an example of an effort to integrate actuarial risk assessment and consensus-based assessment of child and family needs into child welfare practice (Kim et al., 2008). In the SDM model, a case worker uses a consensus-based safety assessment at points throughout the case to determine whether a child can safely remain in his or her home, as well as an actuarial risk assessment to determine the level of risk (high, medium, or low) that a child will experience a recurrence of abuse or neglect in the long term. These assessments of risk and safety are complemented by a consensus-based family strengths and needs assessment, which is used to identify relevant services. This approach was developed and is trademarked by the National Center for Crime and Delinquency (CWIG, 2013c; NCCD, 2013).

In their research using SDM©, Shlonsky and Wagner (2005) identify the process of evidence-based practice as the key to linking the predictive power of actuarial risk assessment with the choice of effective services based on structured needs assessment. Building on their work, Schwalbe (2008) suggests further theoretical refinement of the link between actuarial risk assessment and the identification of needs for the purposes of case planning,

arguing that the distinction is not between risk factors and needs but between static and dynamic risks. Empirical testing of these theoretical models will be critical to understanding the best practices to support caseworkers’ decision making about safety, risk, and interventions. As states, localities, and tribes implement such efforts, it will also be important to ensure that they are integrated with other practice efforts and that staff have the necessary competencies to make these clinical judgments, suggesting the continuing need for evaluation and implementation research.

Differential Response

An innovation over the past 20 years, one that is encouraged by the 2010 reauthorization of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, is differential or alternative response, also referred to as dual-track, multitrack, or multiple-response systems (QIC-DR, 2011). The several differing names are just one indication that this innovation has been implemented quite differently across states. The term “differential response” is used here to denote the various processes by which child welfare agencies have implemented a differential way of responding to child abuse and neglect cases based on the severity of the alleged abuse or neglect and the child’s needs (Casey Family Programs, 2012). An overview of differential response is available from the Quality Improvement Center on Differential Response,8 funded by the Children’s Bureau.

Differential response offers multiple pathways for addressing the needs of children and families referred to child welfare services. In its simplest form, child abuse and neglect referrals are screened and, based on level of risk and other criteria, referred to either an assessment pathway or a traditional investigation pathway. Low- or moderate-risk families are often assigned to the assessment pathway, whereby workers assess the strengths and needs of families and offer services to address those needs, engaging families in the planning of services (QIC-DR, 2011). No formal determination is made regarding the alleged abuse or neglect, and families may decide to accept or refuse services (QIC-DR, 2011). Families are assigned to the traditional investigation pathway when they are at moderate to high risk; the child abuse and neglect type is sexual abuse, serious physical abuse, or other abuse and neglect types designated by the state (e.g., serious neglect in some states); and when other state-specific criteria are met (e.g., age of the child, precipitating factors) (Merkel-Holguin et al., 2006).

Differential response systems allow workers to reassign families from the assessment pathway to investigation if higher risk is discovered, and

________________

8See http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/departments/pediatrics/subs/can/DR/Pages/DiffResp.aspx (accessed January 27, 2014).

in some states workers may reassign families from the investigation to the assessment pathway (Merkel-Holguin et al., 2006; QIC-DR, 2012). This approach is intended to provide an engaging service array for low- or moderate-risk families, supporting the well-being of children and families while still protecting child safety and avoiding future involvement with child protection systems (QIC-DR, 2011).

Tremendous growth has occurred in the implementation of differential response systems over the two decades since the first two states piloted the approach in 1993 (QIC-DR, 2011). Currently, differential response systems have been implemented in 21 states, the District of Columbia, and four tribes (QIC-DR, 2012). Another state (Maryland) enacted legislation requiring a study of differential response, and currently has a bill in the state legislature proposing the establishment of a differential response system beginning in 2013 (NCSL, 2012). In addition, some states and localities have implemented this approach without legislation to guide them (QIC-DR, 2012). Three-quarters of the above 21 states and the District of Columbia have implemented differential response statewide, and the remaining states have implemented it regionally in pilot sites (QIC-DR, 2012). More states (n = 12) are planning or considering the implementation of differential response (QIC-DR, 2012), including one state (Florida) that previously discontinued the approach (QIC-DR, 2011). A few states (Arizona, Arkansas, West Virginia) have discontinued the use of differential response (QIC-DR, 2012).

Privatization

Also known as “outsourcing,” “public-private partnership,” or “community-based care,” child welfare privatization involves an arrangement in which private agencies assume responsibility for public child welfare functions. Privatization is a cross-cutting issue because of the variety of child welfare services that can be outsourced, including case management, family preservation and support, contracting, referral, foster care, and adoptions. In Florida, all child protection functions have been outsourced except for child protection investigation (Armstrong et al., 2008), although in most instances, states that have pursued privatization of their case management functions have not privatized child protection functions. The private-sector provision of child welfare services has a long history, even predating the rise of public child welfare agencies, entailing an array of family services and child welfare and residential agencies, many of which were under sectarian auspices. With the growth of the public child welfare system, many states contracted with private agencies for specific services, and public funding has become an increasing source of revenue for private agencies over the past 30 years (Collins-Camargo et al., 2011). In recent

years, however, states have begun to pursue contracting out not just child welfare services but also their case management functions.

To understand the evolving roles of private agencies in the provision of public services, HHS’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation undertook a series of studies to understand privatization efforts, their rationale, and their implications (ASPE, 2009). The major focus was on the privatization of the case management functions—how it affects placement, placement stability, decision making, court efforts, staffing, and all of the processes needed to meet the needs of abused and neglected children in the child welfare system (ASPE, 2008b).

Models of Family and Parent Engagement

Since the 1993 NRC report was published, child welfare systems have expanded their efforts to engage families, especially parents (including fathers), more fully as part of the service planning and intervention process. Findings of the CFSRs indicated that agencies had difficulty involving parents and children in case planning, and 46 states addressed this issue in their Program Improvement Plans. The findings of the CFSRs suggested that agencies had difficulty with family engagement because of (CWIG, 2012a)

• Staff lacking the skills needed for family engagement in case planning (42 states);

• Staff attitudes and behaviors (25 states);

• Organizational issues (e.g., high workloads) (21 states);

• Parent attitudes, behaviors, or conditions that impede active involvement in case planning (17 states);

• Difficulties created by court-related requirements (14 states); and

• System issues and documentation requirements precluding the production of a written case plan in a family-friendly format (17 states) (CWIG, 2012a, pp. 7-8).

Safe and stable families legislation and community-based child abuse prevention efforts have been among the forces that have promoted a number of family engagement models (see Center for the Study of Social Policy, Kempe Centre Family Group Decision-making, Friends National Resource Center, for information on different models). Family group decision making is one key model, found in 29 states (CWIG, 2012a, p. 8). This model has been broadly disseminated and vigorously promoted since the late 1990s by the American Humane Association’s Child Division (now housed at the Kempe Center). Parent engagement models such as Parents Anonymous (discussed below in the section on models of parent and family engagement) also have long-standing connections with child protection programs

in addressing child abuse and neglect through promotion of a self-help and parent leadership model.

RESEARCH ON KEY POLICY AND PRACTICE REFORMS

The years since the 1993 NRC report was issued have seen improved access to and use of empirical data that are now having a greater influence on decision making. As will be described, focus on the use of administrative and case data to inform child welfare practices has increased. As states and localities use these data, agencies begin to examine differences in decision making among workers and to develop services that are more responsive to the age of the child and the characteristics of the parents (e.g., mothers experiencing depression or parents who abuse substances or have disabilities). Reforms also are being driven by the findings of the federally funded NSCAW, which provide a fuller picture than was previously available of the characteristics of children, families, and workers involved in the child welfare system.

The NSCAW, mandated under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, Sec. 429A,9 has been under way since 1997, with two cohorts of children being enrolled. Data are drawn from first-hand reports from children, parents, and other caregivers, as well as reports from caseworkers and teachers and data from administrative records. The NSCAW is a nationally representative, longitudinal survey of children and families who have been the subject of investigation by child protective services. The study examines child and family well-being outcomes in detail and seeks to relate those outcomes to experience with the child welfare system and to family characteristics, the community environment, and other factors (OPRE, 2013). It is the first longitudinal study in the child welfare field to collect information directly from children and families. The Cohort 1 phase of the NSCAW collected information 5 to 7 years following investigation by child protective services. Because of budget restraints, the Cohort 2 phase is collecting data only over the course of 3 years, and additional funds for further study are not available.

Another data source that provides useful information at the national level is the FCDA.10 Containing the records of more than 2 million chil-

________________

9P.L. 104-193.

10As a resource for social scientific research, the archive was designed deliberately to capture children’s experiences in foster care using a life-course, social ecological lens, making it possible to overlay those experiences onto age-graded trajectories that provide a basis for understanding whether placement happens and when in the life course it is most likely to happen. From the socioecological perspective, it is known that where children live exerts a strong influence on what happens to them over the life course. All of the state data in the FCDA are available at the county level, which includes a link to relevant time-series census

dren, the FCDA is the oldest reliable source of data on foster care, dating back as far as 1976. For the 25 states that contribute data to the archive today, the FCDA maintains a harmonized record of placement through each revision to the state’s data. The discussion below uses information on the experiences of abused and neglected children in the child welfare system drawn from FCDA data for 2003 to 2010, when coverage within the archive reached as high as 70 percent of all foster children in the United States, depending on the question posed. The FCDA is the closest thing to a record of exactly what happened to 2 million children placed away from home in the United States.

A more accurate picture of the experiences of abused and neglected children in the child welfare system has allowed researchers to better evaluate the effectiveness of programs and services. As will be discussed in Chapter 6, child welfare agencies, along with other service providers, now have a robust array of proven model programs on which to draw in designing service practices. However, more research is needed to devise strategies for replicating these models across the varied settings and localities in which children and families receive care.

Title IV-E Waivers

As discussed previously, Title IV-E waivers have been used to target service strategies, including subsidized guardianship and kinship permanence; flexible funding to local child welfare agencies; managed care systems; services for caregivers with substance abuse disorders; intensive services, including expedited reunification; and adoption and post-permanency services (Patel et al., 2012). Many of these initiatives required extensive evaluation, in several cases using random assignment in experimental designs.

In Illinois, the first 10 years of a subsidized guardianship demonstration that used random assignment and an experimental evaluation design saw the state’s foster care population shrink from 51,000 children in 1997 to 16,000 in 2007. The subsidized guardianship waiver allowed the state to use millions of dollars in IV-E reimbursements for child welfare services and system improvements that it otherwise would not have been able to accomplish (Testa, 2010). The strong evidence resulting from the demonstration’s experimental evaluation design encouraged five additional states to apply for waivers to replicate the Illinois strategy, and as previously noted, the findings from these programs resulted in reauthorization in the Fostering Connections Act to use Title IV-E dollars to fund guardianship subsidies.

data. In some states, the geographic data are available at the block group level, a vantage point from which one may assess close up where placement as a response to child abuse and neglect fits into the community narrative.

Several states that used Title IV-E waivers only to allow more flexible use of funds, without a specific program focus, had less clear outcomes. Absent an experimental evaluation design, determining whether changes are due to the waiver or to broader social, economic, and demographic influences is more difficult (HHS 2005 synthesis of findings from IV-E flexible funding child welfare waiver demonstrations).

Differential Response

The literature examining differential response has uncovered some key considerations for the design and implementation of differential response systems. Examples are shown in Boxes 5-2 and 5-3. Box 5-2 presents core components of differential response, developed by Merkel-Holguin and colleagues (2006), while Box 5-3 presents core values to be included in the noninvestigation pathway of differential response, derived by Kaplan and Merkel-Holguin (2008).

The growth in the use of differential response systems has been accompanied by evaluations in some states, as well as the establishment of the federally funded National Quality Improvement Center for Differential

BOX 5-2

Core Elements of Differential Response

• The use of two or more discrete responses of intervention;

• The creation of multiple responses for reports of maltreatment that are screened in and accepted for response;

• The determination of the response assignment by the presence of imminent danger, level of risk, and existing legal requirements;

• The capacity to re-assign families to a different pathway in response to findings from initial investigation or assessment (e.g., a family in the alternative response pathway could be re-assigned to the investigation pathway if the level of risk of the child is found to be higher than originally thought);

• The establishment of multiple responses is codified in statute, policy, and/or protocols;

• Families in the assessment pathway may refuse services without consequence as long as child safety is not compromised;

• No formal determination of child abuse and neglect is made for families in an assessment pathway, and services are offered to such families without any such determination; and

• No listing of a person in an assessment pathway as a child abuse and neglect perpetrator in the state’s central registry of child abuse and neglect.

SOURCE: Merkel-Holguin et al., 2006, pp. 10-11.

BOX 5-3

Core Values for a Differential Response

Non-investigative Pathway

• Family engagement versus an adversarial approach;

• Services versus surveillance;

• Labeling as “in need of services/support” versus “perpetrator”;

• Being encouraging with families versus threatening;

• Identification of needs versus punishment; and

• A continuum of response versus “one size fits all.”

SOURCE: Kaplan and Merkel-Holguin, 2008, p. 7.

Response in Child Protective Services (QIC-DR). Evaluations of differential response systems have been undertaken with varying levels of rigor (QIC-DR, 2011). To the committee’s knowledge, just three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of the approach have been conducted, including studies in Ohio (Loman and Siegel, 2012), Minnesota (Siegel and Loman, 2006), and one county in New York (Ruppel et al., 2011). In each RCT, families that met the criteria for the assessment pathway were randomly assigned to receive either the assessment pathway or traditional investigation services, allowing comparison of outcomes for similar groups of families. Random assignment yielded equivalent groups in one study (Loman and Siegel, 2012) and groups that were similar on all measured characteristics except history of child protective services/previous case, which the researchers statistically controlled for, in the other two studies (Ruppel et al., 2011; Siegel and Loman, 2006). Administrative data were used for most measures, minimizing problems with attrition but also limiting the quality of measurement of outcomes related to developmental well-being.

In addition to the RCTs, seven quasiexperimental studies have evaluated differential response systems using comparison groups of matched sites or families, supplemented in two states by pre-post data comparisons (QIC-DR, 2011). Another 10 states have only monitored administrative data as they implemented their differential response systems (QIC-DR, 2011).

Results from the most rigorous evaluations—three RCTs of differential response—indicate better outcomes for families on an assessment pathway compared with investigated families. Overall, these studies suggest that differential response maintains or increases safety of children, increases

access to services, and increases family satisfaction with services. Findings include the following:

• Child safety was maintained. Evaluators found that children in families following the assessment pathway were as safe as or safer than investigated families as measured by administrative data. The assessment pathway families were the basis for similar (Ruppel et al., 2011) or significantly lower numbers of subsequent screened-in child abuse and neglect reports (Loman and Siegel, 2012; Siegel and Loman, 2006) compared with traditionally investigated families. Because this finding is based on administrative data rather than direct measures of safety, however, it must be interpreted carefully, because the differential response process could plausibly result in less involvement of any agency with the children, who could then be less likely to be rereported even though they were being reabused.

• Fewer removals from home occurred. Children in families receiving assessments were also less likely to be removed from home (Loman and Siegel, 2012; Siegel and Loman, 2006) than those in families subject to the investigation pathway.

• Access to services increased. Among families responding to follow-up surveys, those receiving assessments reported increased access to services compared with investigated families (Loman and Siegel, 2012; Ruppel et al., 2011; Siegel and Loman, 2006).

• Families were more satisfied. Families receiving assessments reported higher levels of satisfaction than investigated families (Ruppel et al., 2011; Siegel and Loman, 2006).

Quasiexperimental studies and natural experiments have yielded similar results, including similar or increased levels of safety (Loman and Siegel, 2004; QIC-DR, 2011), increased access to services (QIC-DR, 2011), and increased cooperation and satisfaction (Loman and Siegel, 2004; QIC-DR, 2011) for families in the assessment pathway compared with those in the investigation pathway. However, several studies have found no positive impact on removals from home (e.g., Loman and Siegel, 2004), and one of the three RCTs did not report a finding on removals (Ruppel et al., 2011).

In addition to positive outcomes for families, evidence suggests that differential response systems cost less in the long term. In a cost-benefit analysis, differential response was identified as an evidence-based policy associated with improved outcomes that has a positive benefit-to-cost ratio ($8.88), thus being highly likely to have a net positive value and save taxpayers money (Lee et al., 2012). This analysis was based on the three RCTs discussed above, as the analysts opted to use only studies of high

rigor. Results of the examination of costs in individual studies are, however, mixed. In one study (Siegel and Loman, 2006), the researchers reported that the initial average costs for the assessment group were higher, but over the longer term, the average cost per assessment family ($3,688) was lower than the cost per investigated family ($4,967). In another study (Loman et al., 2010), also included in the cost-benefit analysis (Lee et al., 2012), the researchers found that on average, overall costs were somewhat higher for assessment families ($1,325) than for investigated families ($1,233).

Results from existing RCTs are promising, and consistent with findings from less rigorous evaluations. However, the number of rigorous evaluations of differential response systems is low. More rigorous evaluations are needed to understand what factors guide successful implementation and ensure desired outcomes and to learn the extent to which the differential response approach works within different contexts. Knowledge also is needed of how different definitions of abuse and neglect, varied criteria for the assessment pathway, unique approaches to service provision, and adequate funding for services contribute to outcomes. Perhaps most critically, there is a need for studies that do not rely solely on administrative data. Fortunately, three additional RCTs and a cross-site evaluation are under way to add to the evidence base (QIC-DR, 2011). As more rigorous studies emerge, additional cost-benefit analyses will be needed as well, including examination of costs associated with different differential response models. At the same time, states should initiate or continue with state-specific evaluations to understand the ongoing impact of their differential response systems.

Privatization

Privatization efforts have undergone limited evaluation, and most applicable studies have methodological shortcomings that limit the generalizability of their results. Evaluation studies included mainly quasiexperimental designs or qualitative analyses of implementation processes. The committee was unable to identify any RCTs of the privatization of child welfare services. A quasiexperimental study (Yampolskaya et al., 2004) analyzed longitudinal administrative data in Florida to compare outcomes for 4 counties using community-based care with those for 33 counties using traditional public care. Results of this study suggested that the performance of counties using community-based care was similar to that of counties not using this approach; however, this study had several methodological limitations, and thus its results should be interpreted with caution.

Three qualitative studies have focused on barriers to implementation. Yang and van Landingham (2012) conducted a qualitative case study of contract monitoring in Florida. Barillas (2011) conducted a historical review of three states (Florida, Kansas, Texas) in an effort to examine the

implementation of outsourced case management. And Flaherty and colleagues (2008) examined implementation processes by conducting focus groups with participants from 12 states. Two common themes emerged from these implementation studies: the key role of politics in privatization and the critical importance of strategic planning before crafting legislation that forces outsourcing. Because government outsourcing often occurs as a reaction to a tragic event, political pressures can lead to ignoring strategic planning and creating overly aggressive implementation schedules and procedures. Yang and van Landingham (2012) suggest that states contemplating whether to outsource services should consider several key questions, including Is privatization economically desirable? Is it administratively feasible? Is it socially and democratically controllable? Is it politically viable? Is it legally appropriate? Identification of measurable performance indicators should also be a key part of the strategic planning process (Flaherty et al., 2008; Yampolskaya et al., 2004). Finally, time and learning play important roles in the successful implementation of privatization; unfortunately, political environments often do not allow the time necessary for systems to mature and management capacities to fully develop (Yang and van Landingham, 2012).

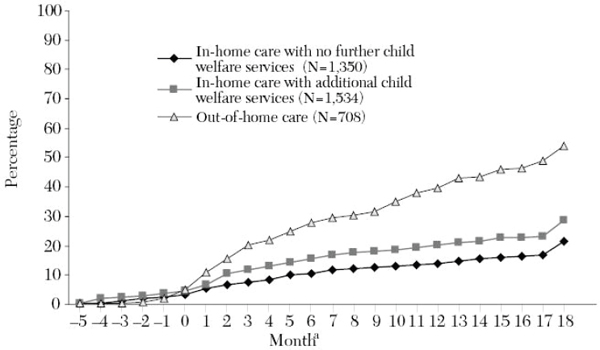

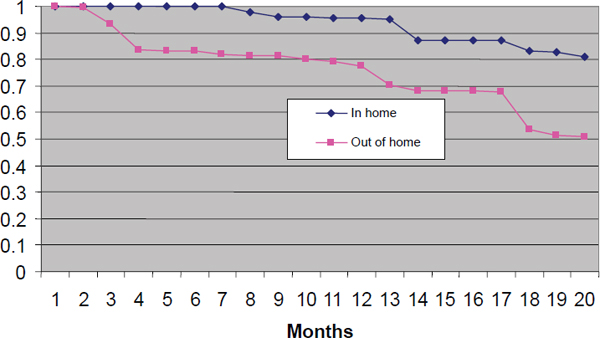

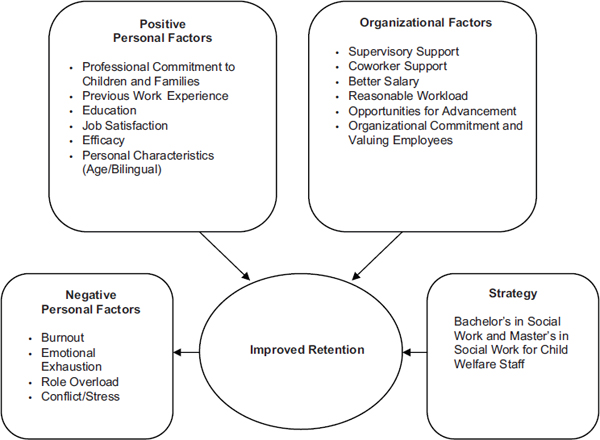

Empirical evidence on the benefits of privatization is limited. Because the focus of recent studies is largely on implementation, further research is required to better understand the effectiveness of specific privatization efforts. The heterogeneity of the field complicates evaluation, as the scope of privatization efforts ranges from very limited performance-based contracts to large, statewide initiatives. Single case studies such as those reviewed above have limited generalizability and would benefit from replication. Future research also should include cost-benefit analyses of privatization. Privatization of the differential response assessment pathway is one area ripe for evaluation. One quasiexperimental study evaluating a differential response program that entails privatizing the assessment pathway through family resource centers (Siegel et al., 2010) yielded promising results, but a more rigorous design and comparison with a publicly provided assessment pathway are needed. Future studies with experimental designs and more robust measurement of effects could examine differences in outcomes and costs between a privatized assessment pathway and public provision of this pathway.