3: Toolkit Part 1: Introduction

During a disaster, decision makers, health care providers, responders, and the general public are confronted with novel and urgent situations. Efficient, effective, and rapid operational decision-making approaches are required to help the emergency response system take proactive steps and use resources effectively to provide patients with the best possible care given the circumstances. It is also essential to develop fair, just, and equitable processes for making decisions during catastrophic disasters in which there are not enough resources to provide all patients with the usual level of care. Decision-making approaches should be designed to address a rapidly evolving, dynamic, and often chaotic set of circumstances. Information is often incomplete and contradictory. Agencies and stakeholders need to understand what information is available to support operational decision making in this kind of situation, and what triggers may automatically activate particular responses or may require expert analysis prior to a decision. This toolkit is intended to help agencies and stakeholders have these discussions.

The objective of this toolkit is to facilitate a series of meetings at multiple tiers (individual agency and organization, coalition, jurisdiction, region, and state) about indicators and triggers that aid decision making about the provision of care in disasters and public health and medical emergencies. Specifically, the toolkit focuses on indicators and triggers that guide transitions along the continuum of care, from conventional standards of care to contingency surge response and standards of care to crisis surge response and standards of care, and back toward conventional standards of care. The toolkit is intended as an instrument to drive planning and policy for disaster response, as well as to facilitate discussions among stakeholders that will help ensure coordination and resiliency during a response.

Box 3-1 presents descriptions of key terms and concepts. This toolkit (presented in Chapters 3-9 of the report) is designed to be able to stand alone, although interested readers will find additional background information and more nuanced discussion of key concepts related to indicators and triggers in Chapters 1 and 2.

This toolkit focuses on operational planning and the development of indicators and triggers for crisis standards of care (CSC). Public engagement is also a key element of CSC planning; a toolkit for community

BOX 3-1

Key Terms and Concepts

Crisis standards of care: “Guidelines developed before disaster strikes to help health care providers decide how to provide the best possible medical care when there are not enough resources to give all patients the level of care they would receive under normal circumstances” (IOM, 2012, p. 6-14).

Continuum of Care: Conventional, Contingency, and Crisis

Conventional capacity: The spaces, staff, and supplies used are consistent with daily practices within the institution. These spaces and practices are used during a major mass casualty incident that triggers activation of the facility emergency operations plan (Hick et al., 2009).

Contingency capacity: The spaces, staff, and supplies used are not consistent with daily practices, but provide care that is functionally equivalent to usual patient care. These spaces or practices may be used temporarily during a major mass casualty incident or on a more sustained basis during a disaster (when the demands of the incident exceed community resources) (Hick et al., 2009).

Crisis capacity: Adaptive spaces, staff, and supplies are not consistent with usual standards of care, but provide sufficiency of care in the context of a catastrophic disaster (i.e., provide the best possible care to patients given the circumstances and resources available). Crisis capacity activation constitutes a significant adjustment to standards of care (Hick et al., 2009).

Indicators and Triggers

Indicator: A measurement, event, or other data that is a predictor of change in demand for health care service delivery or availability of resources. This may warrant further monitoring, analysis, information sharing, and/or select implementation of emergency response system actions.

conversations on CSC is available in the Institute of Medicine’s report Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response (IOM, 2012).

Toolkit Design

The discussion toolkit is structured around two scenarios (one slow-onset and one no-notice), a series of key questions for discussion, and a set of example tables. The example indicators and triggers encompass both clinical and administrative indicators and triggers. The toolkit is designed to facilitate discussion to drive the planning process.

Trigger: A decision point that is based on changes in the availability of resources that requires adaptations to health care services delivery along the care continuum (contingency, crisis, and return toward conventional).

Crisis care trigger: The point at which the scarcity of resources requires a transition from contingency care to crisis care, implemented within and across the emergency response system. This marks the transition point at which resource allocation strategies focus on the community rather than the individual.

Steps for Developing Useful Indicators and Triggers

The following four steps should be considered at the threshold from conventional to contingency care, from contingency to crisis care, and in the return to conventional care. They should also be considered for both slow-onset and no-notice incidents.

1. Identify key response strategies and actions that the agency or facility would use to respond to an incident. (Examples include disaster declaration, establishment of an emergency operations center [EOC] and multiagency coordination, establishment of alternate care sites, and surge capacity expansion.)

2. Identify and examine potential indicators that inform the decision to initiate these actions. (Indicators may be comprised of a wide range of data sources, including, for example, bed availability, a 911 call, or witnessing a tornado.)

3. Determine trigger points for taking these actions.

4. Determine tactics that could be implemented at these trigger points.

Note: Specific numeric “bright line” thresholds for indicators and triggers are concrete and attractive because they are easily recognized. For certain situations they are relatively easy to develop (e.g., a single case of anthrax). However, for many situations the community/agency actions are not as clear-cut or may require significant data analysis to determine the point at which a reasonable threshold may be established (e.g., multiple cases of diarrheal illness in a community). In these situations, it is important to define who is notified, who analyzes the information, and who can make the decision about when and how to act on it.

This chapter provides part 1 of the toolkit, which covers material that is relevant to all components of the emergency response system, including the scenarios and a set of overarching questions. Part 2 of the toolkit is provided in Chapters 4-9, which are each aimed at a key component of the emergency response system: emergency management, public health, behavioral health, emergency medical services (EMS), hospital and acute care, and out-of-hospital care. These chapters provide additional questions intended to help participants drill down on the key issues for their own discipline. These chapters also contain a table that provides example indicators, triggers, and tactics across the continuum of care. This is followed by a blank table for participants to complete.1 The scenarios, questions, and example table are intended to help facilitate discussion around filling in the blank table.

These scenarios are provided to facilitate discussion and encourage practical thinking, but participants

____________________

1 The blank table for participants to complete can be downloaded from the project’s website: www.iom.edu/crisisstandards.

should consider a range of different scenarios—based on their Hazard Vulnerability Analysis—when developing indicators and triggers for their organization, jurisdiction, and/or region. The toolkit provides examples, but does not provide specific indicators and triggers for adoption. This discussion sets a foundation for future policy work, planning, and exercises related to CSC planning and disaster planning in general. The indicators and triggers developed for CSC planning purposes are subject to change over time as planned resources become more or less available or circumstances change. It will be important to regularly review and update CSC plans, including indicators and triggers.

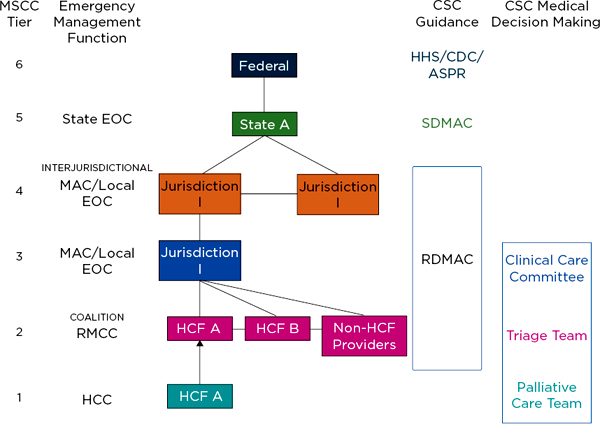

Overarching Key Participants

This toolkit has been designed to be scalable for use at multiple levels. Discussions need to occur at the facility, organization, and agency levels to reflect the level of detail about organizational capabilities that is needed for operational decision making. Discussions also need to occur at higher levels of the emergency response system to ensure regional consistency and integration; it is important to understand the situation in other organizations and components of the emergency response system instead of moving unilaterally to a more limited level of care. Depending on the specific community, these discussions may be initiated at different tiers and may occur in a top-down or bottom-up fashion, but at some point, they must occur at all tiers reflected in the Medical Surge Capacity and Capability (MSCC) framework shown in Figure 3-1 (repeated here from Chapter 1). The development of indicators and triggers could be used by planners as an opportunity to benchmark their approaches, thus facilitating both intrastate and interstate coordination. This may be particularly valuable to entities operating in multistate locations.

This planning process is important regardless of the size of an agency; local preparedness is a key element of avoiding reaching CSC. Instead of using the MSCC framework and creating another response framework, some states may have existing regional and state infrastructures for inclusive trauma/EMS advisory councils/committees; the points made above about the importance of including all response partners and ensuring horizontal and vertical integration within and across tiers apply equally, regardless of the specific framework used.

The following participants should be considered for these discussions; additional participants may be brought in for the stakeholder-specific discussions and are listed in subsequent chapters:

• State and local public health agencies;

• State disaster medical advisory committee;

• State and local EMS agencies (public and private);

• State and local emergency management agencies;

• Health care coalitions (HCCs) and their representative health care organizations, and where appropriate, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers and Military Treatment Facilities that are part of those HCCs;

• State associations, including hospital, long-term care, home health, palliative care/hospice, and those that would reach private practitioners;

• State and local law enforcement agencies;

• State and local elected officials;

• State and local behavioral health agencies;

• Legal representatives and ethicists; and

• Nongovernmental organizations that may be impacted by implementation of CSC (AABB, American Red Cross local chapter, etc.).

When Should These Discussions Take Place?

For communities that have already begun to develop CSC plans, this toolkit can be used to specifically develop the indicators and triggers component of the plan. For communities that are in the early phases of the CSC planning process, the use of this toolkit, and the exploration of community-, regional-, and state-derived indicators, triggers, and the process by which actions are then taken, would be an excellent place to start this important work. It provides much of the needed granularity about what it means to transition away from conventional response and toward the delivery of health care that occurs in the contingency arena, or in worst cases, under crisis conditions. For additional guidance on the development of CSC plans, including planning milestones and templates, see the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) 2012 report.

FIGURE 3-1

Integrating crisis standards of care planning into the Medical Surge Capacity and Capability framework.

NOTES: See Table 2-2 in IOM (2012) for further detail and description of the functions of these entities. The clinical care committee, triage team, and palliative care team may be established at MSCC tiers 1, 2, or 3. The RDMAC may be established at MSCC tiers 2, 3, or 4, depending on local agreements. The RMCC is linked to the MAC/Local EOC and is intended to provide regional health and medical information in those communities; it functions at MSCC tiers 2-4. ASPR = Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (Department of Health and Human Services); CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CSC = crisis standards of care; EOC = emergency operations center; HCC = health care coalition; HCF = health care facility; HHS = Department of Health and Human Services; MAC = Medical Advisory Committee; RDMAC = Regional Disaster Medical Advisory Committee; RMCC = Regional Medical Coordination Center; SDMAC = State Disaster Medical Advisory Committee.

SOURCE: Adapted from IOM, 2012, p. 1-44.

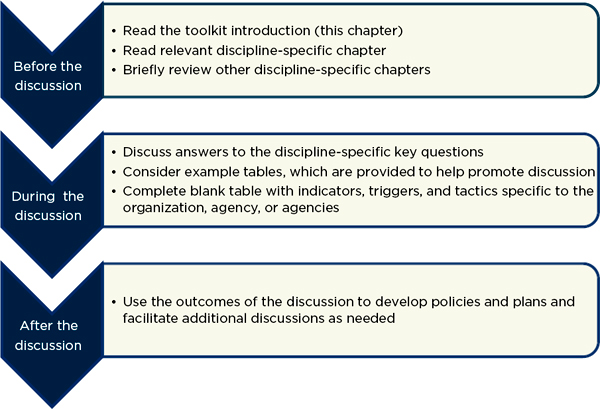

Suggested Process

As noted above, discussions should occur at multiple tiers of the system. A suggested process is provided in Figure 3-2 for discussions at the level of the health care organization, agency, or a small number of related agencies (e.g., EMS and dispatch).

For discussions at higher tiers of the system (e.g., among organizations, coalitions, and agencies from multiple sectors), additional work by participants in advance would be helpful so they arrive having already given thought to the indicators, triggers, and tactics that their own organization or agency would expect to use. Depending on whether this series of discussions is occurring top-down or bottom-up in a given community, this advance work could be done through convening sector-specific discussions first, as described above, or simply through asking each participant to start thinking about his or her own organization’s or agency’s likely actions beforehand.

In particular, it is important to highlight that the two government entities, emergency management and public health, should review the other sections and ensure that the activities they have outlined would support the activities described in the other sections. This would solidify the intent that local and state governmental agencies will need to support health care organizations and HCCs during CSC.

FIGURE 3-2

Suggested discussion process.

NOTES: The example tables are provided to help facilitate discussion and provide a sense of the level of detail and concreteness that will be valuable; they are not intended to be exhaustive or universally applicable. It is important that participants complete the blank table with key indicators, triggers, and tactics that are specific to their organization, agency, or agencies. Depending on the size of the discussion group, it may be most useful for a subgroup of participants to develop the next steps.

To ensure that this aspect of CSC planning is not done in isolation, it would be helpful if the person(s) leading this initiative has/have more in-depth knowledge of the IOM’s 2012 report, in addition to knowledge about the emergency preparedness program within their facility, agency, and/or jurisdiction.

Assumptions

This toolkit assumes that participants have an understanding of baseline resource availability and demand in their agency, jurisdiction, and/or region. The toolkit focuses on detecting movement away from that baseline, and associated decision making.

This toolkit presents common questions, ideas for discussion issues, and example indicators and triggers. Because the availability of resources varies across communities, it is clear that the answers will look very different. That is why this toolkit is a starting point for discussions and is not prescriptive.

Because communities across the nation are at different stages of planning, this toolkit could be used to fill a specific gap in an existing CSC plan, but it also could serve as a first entry point into a larger CSC planning effort.

SLOW-ONSET SCENARIO (PANDEMIC INFLUENZA)2

In early fall, a novel influenza virus was detected in the United States. The virus exhibited twice the usual expected influenza mortality rate. As the case numbers increased, a nationwide pandemic was declared. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the at-risk populations as school-aged children, middle-aged asthmatics, all smokers, and individuals greater than age 62 with underlying pulmonary disease. Vaccine for the novel virus is months away.

Emergency Management

Emergency management has been in communication with public health as this outbreak has unfolded, maintaining situational awareness. They have initiated planning with all key stakeholders as soon as the pandemic was recognized. The county emergency operations center (EOC) was activated, first virtually, then partially, and then fully, as cases began to overwhelm the medical and public health systems. Emergency management has been responding to the logistical needs of public health, EMS, and the medical care system and is coordinating information through a Joint Information System. At the request of local EOCs and the State Health Emergency Coordination Center, the State Emergency Operation Center has been activated. The key areas of focus are coordinating volunteers, providing security, maintaining and augmenting communications, and facilitating coordination of efforts in support of the Emergency Support Function (ESF)-8 agencies. The emergency managers maintain the incident planning cycle and assist ESF-8 personnel in writing daily incident action plans and determining resource needs and sources. Private corporations have given significant support, lending personnel to staff points of dispensing sites, providing home meals to those isolated in their homes or on self-quarantine, and providing logistical support to hotlines and

____________________

2 The two scenarios presented here have been adapted from the two scenarios in Appendix C of IOM (2009). They are provided to encourage discussion and practical thinking, but participants should not confine themselves to the specific details of the scenarios and should consider a range of scenarios based on their Hazard Vulnerability Analysis.

alternate care sites. Later on, when the pandemic winds down, the EOC will help coordinate transition of services toward conventional footing and identify the necessary resources to recovery planning and after-action activities.

Public Health

Local and state public health have been monitoring the status and planning for the pandemic since it was identified through epidemiological data. Multiple health alerts have been issued over the past weeks as conditions or predictions changed and recommendations for targeted use of antiviral medications have been communicated by the State Public Information Officer based on CDC recommendations. Public information campaigns begin, and emergency management and public health convene planning meetings involving key health and medical stakeholders in anticipation of a sustained response. As noted above, vaccine is months away and, when it arrives, may initially be available in only limited quantities. CDC is recommending use of N95 respirators for health care workers. There is an immediate shortfall of N95 respirators in supply chains nationwide and local shortages of antivirals are reported.

Enhanced influenza surveillance has become a standard across the United States and the world. Local health care organizations increased influenza testing and the state laboratory has confirmed that the current strain of influenza virus is present in multiple counties statewide. Volume of laboratory testing has increased substantially in local, regional, and statewide laboratories, which are now looking at current resources and possible modifications to testing protocols.

As the epidemic expands, local and state health EOCs are active 24/7 to support the response. The lead for this incident is the ESF-8, and communications between local and state EOCs in collaboration with the State Health Emergency Coordination Center have been augmented and standardized. Declarations of emergency have been released from the state, including public health emergencies or executive orders consistent with state authorities. Public health and state EMS offices are preparing specific regulatory, legal, and policy guidance in anticipation of the peak impact and subsequent waves. In addition to the activities associated with health, state, and local public health, offices are also addressing other functions, such as human services programs, water quality, food safety, and environmental impact.

EMS

Volumes of calls to 9-1-1 have escalated progressively over time, with high call volumes for individuals complaining of cough and fever. Many high-priority calls cannot be answered during peak hours due to volume. To divert non-emergency calls, hotlines have been established (where available) through which nurses and pharmacists can provide information and prescribe antiviral medications if necessary3; auto-answer systems have also been established to direct callers to Internet-based information.

The state EMS office has been contacted and necessary waivers are under way. The physician or physician board providing medical direction for the EMS agency and the EMS agency supervisor have implemented emergency medical dispatch call triage plans and have altered staffing and transport requirements to adjust to the demand. As public health clinics are overflowing with people demanding medical countermeasures (vaccines and antivirals), there have

____________________

3 See Koonin and Hanfling (2013).

been several reports of violence against health care providers, thefts of N95 respirators from ambulances, and threats against EMS personnel by patients who were informed they do not meet the transport criteria in the disaster protocol.

A recent media report about the sudden death of a 7-year-old child of respiratory failure from a febrile illness has caused significant community concern, sharply escalated the demand on emergency medical dispatch and EMS, and increased workforce attrition throughout the entire emergency response and health care systems.

Hospital

Hospitals have activated their hospital incident command system and moved from conventional care to contingency care as the pandemic worsens. These modifications have been communicated through their regional health care coalition to their local EOC with anticipated support and possible waivers. As patient volumes escalate to nearly double the usual volume, elective surgeries are reduced, intensive care unit patients are boarded in step-down units, inpatients are boarded in procedure and postanesthesia care, and rapid screening and treatment areas are set up in areas apart from the emergency department (ED) for those who are mildly ill. As demand increases, hospital incident commanders are convening their clinical care committees to work with the planning section to prioritize available hospital resources to meet demand, as well as anticipating those resources that may soon be in short supply, including ventilators. Hospitals are sharing ED and inpatient data with the health department. Requests for new epidemiologic and other data have been received. Schools have been dismissed and this, in addition to provider illness, is having a dramatic impact on hospital staffing, as staff who are caregivers are reluctant to use on-site child-care.

Out-of-Hospital

Home care agencies note a significant increase in the acuity and volume of their patient referrals as hospitals attempt “surge discharge” and triage sicker patients within their home. Many home care workers are calling in sick and the agencies are using prioritization systems to determine which clients will be visited on what days. Durable medical equipment across the state providers are starting to identify shortages of home oxygen supplies and devices. Ambulatory care clinics had to clear schedules to accommodate the volume of acute illness. Despite media messages to stay home unless severely ill, many patients are calling their clinics for appointments and information; this is tying up clinic phone lines much of the time. Clinics are struggling to keep infectious and noninfectious patients separated in their facilities. As the epidemic worsened, alternate care facilities started opening to augment care for hospital overflow patients. Hospice patients are being referred to acute care facilities because they can no longer be cared for at home and many do not have their advance directives with them. As the pandemic wanes, many patients who deferred their usual or chronic care during the pandemic, will now present to clinics and EDs, continuing to stress the outpatient care sector.

Behavioral Health

The pandemic has had a tremendous psychological impact. Nearly everyone is exposed to death and illness, either personally or via the media. Houses of worship and other gathering places where people typically get services and support are closed and people are feeling more isolated. Management of decedents is becoming problematic. Hospital and civil morgues and funeral directors are overwhelmed. Coffins and funeral home supplies are in short supply and there

is difficulty getting more. Families of the deceased are becoming increasingly agitated and assertive, demanding that hospitals, medical examiners/coroners, and health authorities take action. Demonstrations about vaccine delays are occurring at hospitals, clinics, and the local health department. Interstate commerce has been affected as restrictions on travel and transport become more pervasive. This is resulting in a noticeable decline in the availability of goods and services. Police are reporting instances of aggression, especially in grocery stores and at ATMs that have not been resupplied. The local and state Department of Social Services is reporting increased calls regarding substance abuse and domestic violence in homes where families have sheltered in place.

Those with preexisting behavioral health conditions are destabilized and require additional support, and many in the population exhibit features of new mental health problems, including anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder. Existing psychiatric patients are also exhibiting increased symptoms as they are not able to obtain their medications. Police, health care workers, and community leaders are reporting substantially increased demand on detox services, and hospitals are discharging chemically dependent and psychiatric patients to make room for other types of patients, which is contributing to some of the problems.

Health care workers and public safety personnel are particularly hard hit by stress, especially those who are not prepared mentally for resource triage. Efforts are being made to “immunize” targeted populations with information on normal and abnormal stress responses, and additional screening and crisis support phone lines have been set up. Conventional outpatient crisis care and inpatient psychiatric care are overwhelmed, and faith-based, volunteer, and other support organizations have to take a much more active role supporting those in crisis in the community. That support is increasingly difficult as needs become more pervasive and severe, and face-to-face individual and group support becomes more difficult.

NO-NOTICE SCENARIO (EARTHQUAKE)

An earthquake, 7.2 in magnitude on the Richter scale, occurred at 10:45 a.m. in a metropolitan area. It also affected multiple surrounding counties that are heavily populated. Along with the initial shaking came liquefaction and devastating landslides. This major quake has shut down main highways and roads across the area to the south, disrupted cellular and landline phone service, and left most of the area without power. Several fires are burning out of control in the metropolitan area. As reports are being received, the estimate of injured people has risen to more than 8,000. Deaths resulting from the earthquake are unknown at this time, but they are estimated to be more than 1,000. Public safety agencies are conducting damage assessments and EMS agencies are mobilizing to address patient care needs. Hospitals and urgent/minor care facilities have been overwhelmed with injured victims. Two community hospitals and an assisted living center report extensive damage. Patients and residents are being relocated to alternate care centers; however, these options are unsuitable for those requiring a higher level of medical support due to lack of potable water and loss of electrical power at several facilities. Outpatient clinics and private medical practices are woefully understaffed or simply closed.

Emergency Management

State, county, and local EOCs have been activated. The governor has provided the media with an initial briefing. As outlined in the National Response Framework, they are attempting to coordinate with EOCs in non-

impacted areas and neighboring states, as well as the federal government, in order to mobilize resources to send into affected areas.

Local EOCs in the impacted area are trying to gain situational awareness through damage assessments, communication with stakeholders about utility failures, road access, injuries, and structural damage. EMS and public health have representatives at the EOCs (public health represents the health care sector for the jurisdiction, including liaison to the health care coalition, by prior agreement). Widespread impacts on hospitals will require that those facilities be evacuated, but EMS is taxed by incident-related demands and difficult road access.

Public Health

The state ESF-8 agency has mobilized resources from unaffected areas and is working with the state emergency management agency/state EOC to request assistance via Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) for vehicles and personnel. The governors of the surrounding states have dispatched medical and search and rescue teams. Public health authorities are inundated with the flow of information and requests for public health and medical assistance coming in to the ESF-8 desk at the local level. The State Health Emergency Coordination Center is fully activated to support the health and public health sectors. Public health authorities are working to initiate “patient tracking” capabilities, and have been asked to support activation of family reunification centers. Health care facilities needing evacuation are calling asking for assistance, including the mobilization of additional personnel resources (e.g., Medical Reserve Corps). Coordinated health and safety messages are providing information pertaining to boil water orders, personal safety measures around gas leaks, downed power lines and active fires, and a description of what resources are being mobilized to respond to this catastrophic disaster event.

EMS and First Responders

Uncontrolled fires have erupted due to broken gas lines. The local fire agencies are unable to respond to all requests for assistance due to broken water lines, difficult access, and the number of fires and damaged structures that have been reported. Only priority structure fires (e.g., fires in or near buildings suspected of containing occupants or hazardous materials) are receiving assistance. Fire departments from counties experiencing less damage are sending whatever assistance they can; however, they are not expected to arrive before evening. Dispatch centers are initiating mutual aid from unaffected counties within the state on request of local and county incident command (IC) through their respective EOCs.

The 9-1-1 emergency lines are inoperable as telephone service has been interrupted by widespread power outages and downed cell towers. The 700 and 800 MHz radios are the most reliable communication because landline and cellular telephone service are inoperative. Many of the injured cannot reach local hospitals due to damaged roads, debris, broken water lines, and power outages that have slowed traffic to a near stand-still. EMS providers report a shortage of staff and vehicles. Air ambulances are temporarily grounded due to foggy and windy conditions, and commercial airports have been closed for an unknown period of time. Unified command has been established and casualty collection points are being identified.

The main freeway is closed due to several collapsed overpasses and road damage, the worst of which has occurred at the freeway interchange. The travel lanes on the overpasses have completely collapsed, trapping at least 12 cars and 2 tourist buses below. The Department of Transportation is assessing structural damage on all freeway overpasses.

The collapse of this segment of the freeway has obstructed or delayed the ability of ambulances and emergency response units to respond to 9-1-1 calls or transport to the local tertiary care facility.

The governor has requested assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), including a Presidential Declaration of Disaster. FEMA will initiate a Joint Field Office as a first step to coordinating federal support for this area. State emergency management has requested EMAC assistance for vehicles and personnel. Governors of surrounding states have dispatched medical and search and rescue teams.

Hospital Care

At one of the hospitals, a 300-bed Level 2 trauma center is occupied at full census, but the administrator activates the Hospital Incident Command System, which opens the hospital command center and activates the disaster response plan. Other area hospitals are also impacted. A damage report reveals that this trauma center is on back-up power and the water supply is disrupted, but there is no major structural damage. Victims are already arriving in the parking lot on foot and by private vehicle as well as by EMS transport. The interhospital radio system is still active, with multiple hospitals reporting significant damage to their hospitals and surrounding routes of access. The administrator recognizes that despite their limitations, they will have to provide stabilizing care to arriving patients. There is no need to imminently evacuate the facility, though appeals for additional staff and a status report are made to the health care coalition coordinating hospitals via radio.

Additional surge care areas are established in the lobby area for ambulatory patients and in an ambulatory procedure area for nonambulatory patients. Surgeons perform basic “bailout” procedures, but the sterile supply department will have difficulty resterilizing surgical trays with available potable water. The administrator works with established material management departments and hospital staff to take stock of materials that may be in shortage and recommend conservation strategies for oxygen, medications (including antibiotics and tetanus vaccine), and other supplies. Off-shift staff members are having trouble accessing the hospital, and many staff present are not able to reach family members—some have left to go find their families, some have stayed to work extra shifts. Blood supply is limited, with resources already being used for the first cases to arrive. There are limited capabilities to manage burn patients, which are usually transferred to the regional burn center. Health care coalitions in the affected area, as well as neighboring regions, are activated to support response.

Out-of-Hospital Care

Ambulatory care clinics, private medical practices, skilled nursing and assisted living facilities, dialysis centers, and home health care services are all significantly impacted by the earthquake. Victims of the earthquake and those patients unaffected directly by the disaster, but in need of ongoing support for their chronic medical care services, are all impacted. Patients requiring regularly scheduled dialysis are unable to receive care at their normal dialysis site. Patients dependent on home ventilators are concerned that their back-up power resources, if any, are not likely to last for more than a few hours. The regional health care coalition hospital coordination center works with public health in the local EOC to identify resources for these patients, including the identification of “shelter” options, but many simply head to the hospital as a safe haven. Health care practitioners and professionals are urgently recruited to assist in the establishment of alternate care sites and shelter environments, which are being set up around the perimeter of

the most severely affected areas. Access to medications at pharmacies is significantly impacted, sending more patients seeking assistance to already overtaxed hospitals.

Behavioral Health

The behavioral health unit at the impacted hospital or social work department crisis response staff deploys a small team to respond to patient and staff mental health needs as a standard component of the hospital’s emergency response plan. The hospital lobby is teeming with people who appear shocked and confused. The hospital sets up an emergency triage and assessment unit for persons with minor injuries and those survivors looking for family members, and initiates behavioral health assessment and psychological first aid, targeting those who appear to be disoriented or distraught.

At the hospital, uninjured citizens begin to arrive in large numbers trying to find their loved ones. The hospital has an incomplete and ever-changing list of those being treated and are challenged in the early hours to provide definitive answers to inquiries. Citizens are becoming more anxious and angry. Hospital personnel are attempting to physically sort and separate family members with loved ones being treated in the hospital, searching families, and families of those in the hospital morgue. The number of deceased patients in the hospital morgue is increasing from deaths related to the incident. In addition, community morgue resources are taxed.

Several people (including children) have experienced severe burns, local capacity has been exceeded, and burn patients have been evacuated to burn centers in neighboring jurisdictions. Searching family members are becoming increasingly agitated and demanding when they are unable to learn the whereabouts of their loved ones and/or be reunited with them. Communications about individuals’ locations are being forwarded to governmental support systems such as local and state EOCs, Joint Information Centers, and nongovernmental emergency response agencies.

Some hospital personnel are refusing to come to work until and unless they can be assured of their safety in the hospital as well as the proper care and safety of their children (who are no longer in school).

At the request of local EOCs, the state EOC activates six Medical Special Needs Shelters, which are staffed with behavioral health assessment and intervention teams, and activates behavioral health crisis response teams to assist first responders active in rescue-and-recovery and evacuation activities. Rumors develop that registered sexual offenders or other “risky persons” are among those residing in shelters.

An inpatient forensic psychiatric unit has been damaged and deemed unsafe. Following hospital response plans, arrangements are attempted to move patients to a comparable facility in another county/state. Difficulties are encountered in arranging appropriate transport and the receiving hospital reports very limited bed availability.

The chaos associated with the incident has increased the public’s anxiety that people will die from their injuries while awaiting emergency transport. Risk/crisis communication talking points are disseminated to local officials and the media as to where behavioral health assistance is available.

The following questions reflect overarching common themes that apply to all stakeholder discussions. The discipline-specific portions of the toolkit (Chapters 4-9) include questions that are customized for these disciplines; the overarching questions are included here to facilitate shared understanding of the common issues under discussion by each discipline.

• What information is accessible?

• How would this information drive actions?

• What additional information could be accessed during an emergency and how would this drive actions?

• What actions would be taken? What other options exist?

• What actions would be taken when X happens, where X is a threshold that would signal a transition point in care (e.g., cannot transport all patients, run out of ventilators, cannot visit all the sickest home care patients).

• Do the identified indicators, triggers, and actions follow appropriate ethical principles for CSC? What legal issues should be considered?4

It is important to highlight understanding and attending to the sometimes unique needs of those whose roles include administration of and response to an extreme incident. If their health (including behavioral health) is adversely impacted in ways that impact role function, the entire response can become compromised and, in extreme cases, fail. Preparedness activities should include detailed planning that anticipates and addresses behavioral health consequences for both decision makers and responders. Preparedness activities should address strategies for monitoring the responder population, identifying potential sources of psychological distress, and available interventions, including those geared toward stress reduction and management as well as resilience promotion among these responders. During a response, proactive monitoring of the “temperature” of staff is needed by supervisory personnel, with reports back to the IC, and aggressive measures to maintain morale, manage fatigue, and manage home-related issues for staff.

Table 3-1 below outlines indicators, triggers, and tactics related to worker functional capacity and workforce behavioral health protection. It has the same format as the tables included in the discipline-specific chapters that follow this one. These chapters provide tables with examples of discipline-specific indicators, triggers, and tactics; this is not an exhaustive list. The examples are provided here because this is a crosscutting issue that should be addressed by all sectors to improve the quality of decisions and quantity of available staff. The discipline-specific chapters also discuss strategies to address worker shortages.

Given the focus of this toolkit on decision making, the examples in the table are focused primarily on behavioral health and human factors. It is important to recognize that other areas of workforce protection, such as physical health and safety (including fatigue management), are also critical and should be considered during disaster planning processes. A comparable discussion should take place about other health and medical elements of force protection. In addition, the examples provided here are general approaches to worker functional capacity; for more details on individual topic areas, see the discipline-specific chapter and, in particular, the behavioral health chapter (see Chapter 6).

____________________

4 Ethical considerations are a foundational component that should underlie all crisis standards of care planning and implementation. The Institute of Medicine’s 2009 and 2012 reports provide extensive discussion of ethical principles and considerations. Considerations of legal authority and environment are also a foundational component to CSC planning and implementation. Certain indicators and triggers related to legal issues are included in this toolkit in Chapters 4-9; for additional discussion, see the 2009 and 2012 reports.

Hick, J. L., J. A. Barbera, and G. D. Kelen. 2009. Refining surge capacity: Conventional, contingency, and crisis capacity. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 3(Suppl 2):S59-S67.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Guidance for establishing crisis standards of care for use in disaster situations: A letter report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12749.

IOM. 2012. Crisis standards of care: A systems framework for catastrophic disaster response. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13351.

Koonin, L. M., and D. Hanfling. 2013. Broadening access to medical care during a severe influenza pandemic: The CDC nurse triage line project. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science 11(1):75-80.

TABLE 3-1

Example Worker Functional Capacity Indicators, Triggers, and Tactics for Transitions Along the Continuum of Care

| Indicator Category | Contingency | Crisis | Return Toward Conventional |

| Worker functional capacity |

Indicators: • Employees routinely working more than 150% of usual shift duration • Patient/public complaints increase • Worker complaints about coworkers increase (attitude, decision making, etc.) • Workers begin to exhibit increased signs of stress (physiological, psychological, emotional, behavioral, social) (unit supervisors should be passing on reports to the command center) • Increased sick calls • Coworker perception of excessive fatigue or maladaptive behaviors (inability to make decisions, increased anger, etc.) • Increases in role conflict issues (relative priorities of home/family well-being and job function) reported by unit supervisors or implied by infrastructure damage, school closings, or communications systems failures • Workplace accidents increase • Workers express doubts/problems with their perceived safety or education/training for current tasks • Negative media coverage/public perception of facility/agency response Triggers: • Worker signs of stress or fatigue (physiological, psychological, emotional, behavioral, social) become commonplace • Productivity/function begins to decrease to the extent that supervisory personnel must intervene • X% increase in errors/incidents reported formally or informally to command center • Increases in role conflict (relative priorities of home/family well-being and job function) results in increased difficulty covering shifts/key roles |

Indicators: • Productivity declines further • Errors/incidents increase rate and severity (patients/public are harmed and/or die as a result of errors) • Facility policies and actions cause negative public/media attention or compromised function of operations/ relationships • Role conflict (relative priorities of home/family well-being and job function) increasingly problematic • Workplace accidents continue to increase • Workers decline to assume responsibilities they deem to be high risk Crisis triggers: • Productivity/function problems due to personnel issues cause service disruption • Role conflict (relative priorities of home/family well-being and job function) results reach a point where units are unable to maintain staffing, patients are transferred to other facilities, personnel refuse to come to work • Unable to give workers time off between shifts, at least equal to shift length • Workers are noted to be falling asleep on the job or exhibiting other unsafe behaviors Tactics: • Intensify stress management/resilience promotion training and activities (e.g., psychological first aid) • Continue regular and accurate surveillance of stress-related issues • Continue integration of various stakeholders in strategy development and implementation (e.g., direct care leadership, administration, HR, general counsel, EAP, etc.) |

Indicators: • Workers begin to exhibit decreased signs of stress (physiological, psychological, emotional, behavioral, social) • Productivity/function begins to increase • Errors, incident reports, complaints decrease • Decreases in role conflict (relative priorities of home/family well-being and job function) • Workplace accidents decrease Triggers: • Productivity/function return to baseline • Errors/incident reports return to baseline • Shift schedules and responsibilities return toward baseline Tactics: • Stress management/resilience promotion training and activities (e.g., psychological first aid) become routine part of organizational practices • Evaluate, enhance, and continue regular and accurate surveillance of stress-related issues • Continue integration of various stakeholders in strategy development and implementation (e.g., direct care leadership, administration, HR, general counsel, EAP, etc.) with focus on rewarding staff, memorialization where appropriate, appreciation activities • Scale back or discontinue specialized consultation from content experts in workplace stress • Review, evaluate, and appropriately modify personnel policies and practices • Deactivate mutual aid and other supplemental human resources |

|

Tactics: • Implement stress management/ resilience promotion training and activities (e.g., psychological first aid) • Implement fatigue management policies • Ensure adequate staffing ratios or provide additional personnel support for non-expert duties (lower levels of trained personnel, etc.) • Ensure incident information flow to staff (situational awareness) is maintained, including operational briefings and opportunity for staff to provide input and comment • Liaison/discussions with collective bargaining representatives to avoid conflicts arising from disaster-related staffing changes • Provide support for the staff’s family needs (access to phone lines to call home, providing basic shelter to family members, child care, pet care, etc.) • Provide appropriate nutrition support, including expanded hours of services • Restrict nonessential duties (meetings, etc.) • Ensure regular and accurate surveillance of stress and fatigue-related issues by management/ supervisory staff • Ensure integration of various stakeholders in strategy development and implementation (e.g., clinical care leadership, administration, human resources [HR], legal counsel, employee assistance programs [EAPs], etc.) • Initiate staff appreciation activities • Explore specialized consultation from content experts in workplace stress in extreme situations • Review personnel policies and practices to explore ways in which stress on workers may be reduced, including rotations through other areas of the facility or variable responsibilities • Review and update plans for mutual aid or other means of supplementing human resources |

• Explore specialized consultation from content experts in workplace stress in extreme situations • Implement changes in personnel policies and practices • Activate plans for mutual aid or other means of supplementing human resources, including use of support personnel for all noncritical tasks |

||