This chapter provides a discussion of terminology, a description of the context for the committee’s charge (e.g., Healthy People 2020 and the Affordable Care Act), and an outline of key milestones in the history of quality improvement theory and action in public health and health care.

The language of quality improvement in health care and public health presented the committee with its first challenge. Recognizing that the various concepts and terminology used to refer to quality are not standardized, a situation that leads to some confusion and a lack of precision (see, for example, discussion by Derose et al., 2002; Randolph et al., 2009), the committee sought to use terms consistently in its report (see glossary in Appendix A). Quality in public health has been defined as “the degree to which policies, programs, services and research for the population increase desired health outcomes and conditions in which the population can be healthy” (Public Health Quality Forum, 2008). Although the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) documents on public health quality do not explicitly define quality measures, Derose and colleagues (2002) defined them as “quantitative statements about the capacity (structure), actions (processes), or results (outcomes) of public health practices” (p. 2).1 Similarly, the National Quality Forum (NQF),

___________________

1 Derose et al. (2002) use the term “quality indicators” and the committee considers the terms measures and indicators interchangeable in the context of this report. Also, while recognizing that quality and performance are distinct concepts, the committee finds that the term “performance measures” may be interchangeable with “quality measures.” Unfortunately, none of the possible sources consulted, including materials from federal

which manages its Quality Positioning System for the health care delivery sector, describes its work as “evaluat[ing] and endors[ing] tools for standardized performance measurement, including: performance measures that assess structure, process, outcomes, and patient perceptions of care” (NQF, 2013). A cursory review of the 688 measures in the NQF system reveals a great range: some are measures of outcome (e.g., prevalence of adult tobacco use in the population), while others are more process-oriented (e.g., screening male smokers 65 through 75 years old for abdominal aortic aneurysm). Both definitions of measure provided above reflect the Donabedian framework of quality that has been widely used in health care quality improvement and that has also guided the committee in its development of a conceptual framing or logic model for this report. The definitions also suggest that different kinds of measures may be used in the work of quality improvement—measures of structure, process, and outcomes—and all these may be considered measures of quality.

Measuring and improving quality is a central focus in the health care delivery sector and in the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. However, the issue of quality is relevant to a far broader community of public- and private-sector contributors to the health of the population. Previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports have defined the multi-sectoral health system to include health care organizations (such as hospitals), state and local public health agencies, the education sector (e.g., schools and colleges), business, social services and other community-based organizations, faith-based groups, and many others (IOM, 2003a, 2011a, 2012). This report uses that broad definition of the health system.

The committee used the HHS definition of quality in public health (see Box S-2), with one modification—changing “quality in public health” (i.e., referring to the governmental public health agencies charged with protecting and promoting health in communities) to “quality in the multisectoral health system.” Although the committee recognized that the public health quality work in HHS’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) is grounded in the activities of public health practice, the scope of the Leading Health Indicators (LHIs) (i.e., the inclusion of high school graduation and air quality measures), and the recognition that health is the result of multiple determinants and the ef-

___________________

agencies and from other organizations, shed light on how to distinguish quality and performance. The only obvious difference is that quality refers to a state of being, and performance refers to action, thus, measures of the state of being vs. measures of how well we do what we do (often incorporating attention to cost and efficiency). The committee found that delving more deeply into the language issue was not a productive endeavor.

forts of multiple actors and sectors (also reflected in the Healthy People 2020 chapter on social determinants) makes it necessary to use a more expansive term. Thus, the committee refers to its work as identifying measures of quality for the multisectoral health system, in reference to the multiple contributors to improving health described above.

The more expansive description of the system is supported by comments made by the assistant secretary for health. In giving the committee its charge, he averred that the interface between clinical care and public health is an absolutely crucial arena for identifying and implementing measures of quality.

We are now in a time in the history of our country where we are really joining the worlds of health care and population health. We are joining the worlds of the clinic and the community. We are integrating what happens to people inside of a health care setting to what happens to people outside of a health care setting in the community. And that is where the future of all discussions about public health should lead.2

Although the health care delivery system is increasingly focused on population health, the committee found that focus reflects a relatively narrow interpretation of the term—population as the patient panel or group of covered lives (i.e., individuals insured). The committee preferred the Jacobson and Teutsch (2012) definition of total population health as the health of all persons living in a specified geopolitical area— a definition consistent with the history of public health practice.

In a further elaboration on what is meant by quality, the HHS Public Health Quality Forum outlined the nine aims for improvement of quality in public health, which are also described as characteristics of quality in the public health system. The characteristics are population-centered, equitable, proactive, health-promoting, risk-reducing, vigilant, transparent, effective, and efficient. The committee found the term “characteristics” more clear, and refers to “quality characteristics” in the report. The Public Health Quality Forum defined the characteristics in the following way:

___________________

2 First meeting of the IOM Committee on Quality Measures for the Healthy People Leading Health Indicators, December 3, 2012, at the National Academy of Sciences Building, Washington, DC.

- Population-centered—protecting and promoting healthy conditions and the health for the entire population

- Equitable—working to achieve health equity

- Proactive—formulating policies and sustainable practices in a timely manner, while mobilizing rapidly to address new and emerging threats and vulnerabilities

- Health-promoting—ensuring policies and strategies that advance safe practices by providers and the population and increase the probability of positive health behaviors and outcomes

- Risk-reducing—diminishing adverse environmental and social events by implementing policies and strategies to reduce the probability of preventable injuries and illness or other negative outcomes

- Vigilant—intensifying practices and enacting policies to support enhancements to surveillance activities (e.g., technology, standardization, systems thinking/modeling)

- Transparent—ensuring openness in the delivery of services and practices with particular emphasis on valid, reliable, accessible, timely, and meaningful data that is readily available to stakeholders, including the public

- Effective—justifying investments by utilizing evidence, science, and best practices to achieve optimal results in areas of greatest need

- Efficient—understanding costs and benefits of public health interventions and to facilitate the optimal utilization of resources to achieve desired outcomes

In addition to being asked to identify measures of public health quality within the framework provided by the nine quality characteristics, the committee was asked to comment on the relationship with the six priority areas, also described as drivers, for improvement of quality in public health. These are population health metrics and information technology; evidence-based practices, research, and evaluation; systems thinking; sustainability and stewardship; policy; and public health workforce and education.

The OASH has spearheaded a national collaborative effort to develop a framework for quality in public health that complements ongoing efforts on health care quality, and fits into the larger context of

- Health care reform and the National Quality Strategy, the National Priorities Partnership, the National Prevention Strategy (National Priorities Partnership, 2011; NQF, 2012a).

- Major reports relevant to the nation’s paradox of rising health care costs and poor outcomes (IOM, 2012; Stremikis et al., 2011).3 A growing awareness of the evidence that determinants of health beyond genes, behavior, and health care play an important role in shaping the health of individuals and communities (reflected in the addition of a Social Determinants topic to Healthy People 2020).

- The history of standard setting, performance measurement, and quality improvement in public health, as attested to by the National Public Health Performance Standards, the Turning Point Performance Management National Excellence Collaborative, and more recently, the Multi-State Learning Collaborative associated with the voluntary national accreditation effort led by the Public Health Accreditation Board (Riley et al., 2010).

- Increased availability and use of health indicators, with key examples found in the decades-long national Healthy People effort, the state-oriented America’s Health Rankings and the locally-focused County Health Rankings (IOM, 2011a; Remington and Booske, 2011; United Health Foundation, 2012). A more detailed overview of Healthy People 2020 is provided below.

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020 is a comprehensive set of national objectives for “improving the health of all Americans” and it is the most current version of a long-standing decennial HHS health planning effort. Healthy People 2020 contains 42 topic areas, close to 600 objectives (with additional objectives under development), and 1,200 measures. The Leading Health Indicators represent a “smaller set of Healthy People 2020 objectives,” which “has been selected to communicate high-priority health issues and actions that can be taken to address them” (HHS, 2013).

___________________

3 Studies published at the time of this writing in May 2013 indicated a slowdown in health care spending (Cutler and Sahni, 2013; Ryu et al, 2013)

Although Healthy People 2020 does not explicitly refer to quality, quality in the performance of all partners in the multisectoral system is crucial to achieving desired health outcomes, for example, good schools to support students through graduation, effective health care delivery organizations that provide patient-centered medical homes, and effective public health agencies that serve as knowledge enterprises and help to convene stakeholders around health improvement.

The social determinants of health have been formally incorporated into Healthy People 2020. Koh and colleagues (2011) describe how the social determinants approach informed the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020 and informed the new social determinants topic in Healthy People 2020. The explicit recognition of multiple non-health factors at work in influencing health outcomes opens the door to a wider array of stakeholders. Given this context, the committee’s view is that measures of quality related to the LHIs need not be limited to those outcomes and interventions over which governmental public health departments have direct responsibility or influence. Achieving the Healthy People objectives, and the overarching, aspirational goal of long, healthy lives for all people in the United States clearly requires collaboration with other sectors, within and outside government, and at all geographic levels. Although the nine quality characteristics refer primarily to the governmental public health agencies, it is well understood that public health action is not limited to government, therefore the committee considers the findings and recommendations in this report relevant to partners in health care delivery and in other sectors.

In its survey of measures related to the LHIs (see Box 1-1), the committee noted that many such measures are found in the health care delivery system or in an area of overlap between public health and health care. Changes precipitated by the Affordable Care Act also offer opportunities for health care to expand its role well beyond the patient care, and for public health and health care to work together in new ways. One such example is the expansion of concepts of community benefit offered by tax-exempt hospitals to include community-building activities and collaboration with other sectors in improving the health of the community in a more holistic manner than solely through the patient–provider interaction.

BOX 1-1

Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicator Topics and Leading Health Indicators

1. Access to Health Services

1) Persons with medical insurance (AHS-1.1)

2) Persons with a usual primary care provider (AHS-3)

2. Clinical Preventive Services

3) Adults who receive a colorectal cancer screening based on the most recent guidelines (C-16)

4) Adults with hypertension whose blood pressure is under control (HDS-12)

5) Adult diabetic population with an [hemoglobin] A1c value greater than 9 percent (D-5.1)

6) Children aged 19 to 35 months who receive the recommended doses of DTaP, polio, MMR, Hib, hepatitis B, varicella, and PCV vaccines (IID-8)

3. Environmental Quality

7) Air Quality Index (AQI) exceeding 100 (EH-1)

8) Children aged 3 to 11 years exposed to secondhand smoke (TU-11.1)

4. Injury and Violence

9) Fatal injuries (IVP-1.1)

10) Homicides (IVP-29)

5. Maternal, Infant, and Child Health

11) Infant deaths (MICH-1.3)

12) Preterm births (MICH-9.1)

6. Mental Health

13) Suicides (MHMD-1)

14) Adolescents who experience major depressive episodes (MDEs) (MHMD-4.1)

7. Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity

15) Adults who meet current Federal physical activity guidelines for aerobic physical activity and muscle strengthening activity (PA-2.4)

16) Adults who are obese (NWS-9)

17) Children and adolescents who are considered obese (NWS-10.4)

18) Total vegetable intake for persons aged 2 years and older (NWS-15.1)

8. Oral Health

19) Persons aged 2 years and older who used the oral health care system in past 12 months (OH-7)

9. Reproductive and Sexual Health

20) Sexually active females aged 15 to 44 years who received reproductive health services in the past 12 months (FP-7.1)

21) Persons living with HIV who know their serostatus (HIV-13)

BOX 1-1

10. Social Determinants

22) Students who graduate with a regular diploma 4 years after starting 9th grade (AH-5.1)

11. Substance Abuse

23) Adolescents (12-17 years old) using alcohol or any illicit drugs during the past 30 days (SA-13.1)

24) Adults engaging in binge drinking during the past 30 days (SA-14.3)

12. Tobacco

25) Adults who are current cigarette smokers (TU-1.1)

26) Adolescents who smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days (TU-2.2)

NOTES: AH = adolescent health; AHS = access to health services; C = cancer; D = diabetes; EH = environmental health; FP = family planning; HDS = heart disease and stroke; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IID = immunization and infectious diseases; IVP = injury and violence prevention; MHMD = mental health and mental disorders; MICH = maternal, infant, and child health; NWS = nutrition and weight status; OH = oral health; PA = physical activity; SA = substance abuse; TU = tobacco use.

A SHORT HISTORY OF QUALITY IN HEALTH CARE AND PUBLIC HEALTH

The notion of monitoring and reporting quality in health care is very familiar and well explored. The public health field also has a history of quality improvement initiatives. The Institute of Medicine began its examination of quality in health care soon after its 1970 founding, with the 1974 report Advancing the Quality of Health Care: A Policy Statement (IOM, 1974), and IOM’s work in this area has continued through many influential reports, most notably Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001). In parallel with the IOM work on quality in the late 1990s, the President established the Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality and Health Care in 1996, and that Commission released its report in 1998 (President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry, 1998). On the public health side, the 1997 IOM report Improving Health in the Community: The Role for Performance Monitoring described the components of the community health improvement process, examined the role of performance monitoring in that process, and identified possible tools for communities wishing to develop performance measures.

In 1994, the IOM Council issued a white paper, “America’s Health in Transition: Protecting and Improving Quality” (IOM, 1994), which included the following statement:

Quality can and must be measured, monitored, and improved. Policymakers, whether in the public or the private sector at local, state, or federal levels, must insist that the tools for measuring and improving quality be applied. These approaches require constant modification and reassessment—that is, the continual development of new strategies and the refinement of old ones. Furthermore, credible, objective, and nonpolitical surveillance and reporting of quality in health4 and health care must be explicitly articulated and vigorously applied as change takes place.

The current committee’s work reflects on these ideas in several ways. First, the committee recognized that the topic of quality and quality improvement is complex, and that the concepts and terminology that operate in this realm of quality are not standardized or widely agreed on (see, for example, discussion in Derose et al., 2002; Randolph et al., 2009). Second, the phrases “reporting of quality in health and health care” reflect a distinction that is crucial when talking about quality, and that played an important role in the committee’s deliberations. That is, measuring and improving quality does not apply only to the delivery of health care services, such as in eliminating overuse, underuse, and misuse of medical procedures. As described in Improving Health in the Community (IOM, 1997) and more recently, in For the Public’s Health: The Role of Measurement in Action and Accountability (IOM, 2011a), measurement is essential for improving the health of the population outside the clinical setting—improving health in communities; it shines a light on the social and environmental factors that shape health outcomes (i.e., the determinants of health) and thus helps mobilize people and groups to take action to alter those factors. As recent public health quality efforts in HHS have emphasized, quality also refers to nine characteristics (listed above) that must be present in the delivery of population-based interventions, and more broadly, in implementing any interventions intended (or known) to improve the population’s health. Third, in light of the 1988 definition of public health, that is, “fulfilling society’s interest in assuring conditions in which people can be healthy,” the committee believes that quality in the context of population health im-

___________________

4 Italics added.

provement relates to all the systems (or their contributions) that create conditions that shape a community’s health outcomes. Beyond health care and public health organizations, which are wholly dedicated to health-related goals, the sectors of education, transportation, housing, business, and planning are among those that contribute in different ways to health outcomes. High school graduation, for example, contributes to better health outcomes (Freudenberg and Ruglis, 2007), but is not a factor controlled by governmental public health agencies. Fourth, the committee reiterates the recommendation of the 2011 IOM report For the Public’s Health: The Role of Measurement in Action and Accountability, which echoed others in the field (e.g., Brownson et al., 2010) in calling for measures of a community’s intrinsic health in the sense of health-promoting or health-supporting features of a community, such as walkability, ample green and recreational space, quality housing, adequate healthful food sources, and an information environment that is shaped to support health (e.g., fast food restaurant advertising).

Several IOM reports on quality in health care have defined quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (IOM, 1990, 1998, 1999). One of those reports explained that “viewed most broadly, the purpose of quality measurement [in health care] is to secure for Americans the most health care value for society’s very large investment” (IOM, 1999, p. 2). These reports and the definitions and frameworks they have put forward, along with important work from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and others in the field, have served as part of the foundation for the work of the HHS Public Health Quality Forum (PHQF). The PHQF, convened in 2008 to stimulate “a national movement for coordinated quality improvement efforts across all levels in the public health system” comprises the HHS Office of Public Health and Science, several HHS agencies (HHS, 2012), and also received input from several stakeholder organizations (Public Health Quality Forum, 2008). Building on the 1990 IOM definition, the PHQF defined quality in public health somewhat analogously as “the degree to which policies, programs, services, and research for the population increase desired health outcomes and conditions in which the population can be healthy” (Public Health Quality Forum, 2008). The concept of conditions links to the 1988 IOM report that defined public health, and also to the ever-expanding evidence base on the social and environmental determinants of health. The committee’s charge places its work at the intersection of the Healthy People 2020 population health measurement effort and the public health quality improvement

effort. These two activities, which are both in the OASH, are linked because the ultimate evidence of quality in a system is demonstrated by measures showing good outcomes.

Almost a decade after the 1999 IOM report on quality in health care, HHS released the 2008 PHQF report Consensus Statement on Quality in the Public Health System. The statement built on the work of the 1998 report of the President’s Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry and the IOM report Crossing the Quality Chasm, which in 2001 described the six aims for improvement in quality of care: safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered (see Box 1-1).

Between 2008 and the writing of the present report, several important activities have been launched or conducted that further shape the field and inform the committee’s work to identify quality measures for the 26 LHIs. In 2010, HHS was charged by the Affordable Care Act (ACA)5 to develop a National Strategy for Quality Improvement in Health Care. In March 2011, HHS submitted the National Quality Strategy to Congress, followed in 2012 by the first Annual Report to Congress (Honore et al., 2011). A goal of the National Quality Strategy is to build consensus nationally on how to measure health care quality and align federal and state efforts “to reduce duplication and create efficiencies— not just in measurement but in quality improvement efforts as well” (National Priorities Partnership, 2011, pp. 1-3). The NQF convened more than 50 public and private organizations in the National Priorities Partnership which provides ongoing input on the implementation of the Strategy. The Strategy and the work of NQF were part of the committee’s information gathering, as described elsewhere in the report. The National Quality Strategy also introduced a Three-Part Aim, modeled on the Triple Aim framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in 2006, which called for improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care. Similarly, the Three-Part Aim calls for

- Better care: Improve the overall quality of care, by making health care more patient-centered, reliable, accessible, and safe.

- Healthy people/healthy communities: Improve the health of the U.S. population by supporting proven interventions to address behavioral, social, and environmental determinants of health in addition to delivering higher-quality care.

___________________

5 Section 3011.

- Affordable care: Reduce the cost of quality health care for individuals, families, employers, and government (HHS, 2012).

The second component of the Three-Part Aim clearly identifies a focus on the population as a whole (not merely subpopulations of patients covered by a specific insurer, or patients with a specific condition), consistent with public health theory and with earlier work in HHS.

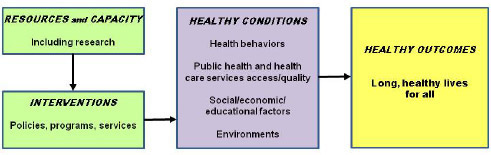

Throughout its deliberations, the committee that produced this report used the logic model shown in Figure 1-1. The model is a simple illustration of the PHQF’s definition of quality: “the degree to which policies, programs, services and research for the population increase desired health outcomes and conditions in which the population can be healthy.” The model is obviously not intended to capture all the complete and complex pathways from inputs to outputs and outcomes that relate to health: it is intended instead to serve as a general guide for how to think about this complex area in the process of identifying measures of quality. The model, which resembles the logic model used by a previous IOM committee (see IOM, 2011a, 2012), shows system structure (Resources and Capacity) and processes (Interventions) on the far left. These influence Healthy Conditions (i.e., the determinants of health), which in turn lead to intermediate and ultimate population health outcomes. The logic model provides a framework for discussing and organizing the LHIs and measures of quality associated with them. The grouping of measures according to domains in a conceptual framework (i.e., logic model) was first used by the developers of the County Health Rankings, as a way to communicate the relationship between health outcomes, their determinants, and the programs and policies that can be used to improve population health (Remington and Booske, 2011).

Viewed from left to right, the model shows concisely the relationship among system inputs and structure, processes, and outputs and outcomes. Resources and Capacity refers to the systems requirements such as funding, a trained and capable workforce, information technology capabilities, and the knowledge base: the six drivers of quality improvement in public health are found here. Research is especially important because it serves as a foundation for policies, programs, and services, which in turn lead to healthy conditions and yield healthy outcomes. In practical terms, identifying measures of quality requires an evidence base that allows one to identify which interventions used to achieve a specific outcome are effective and to determine the extent to which they are effective (magnitude of effect). Absent a strong research enterprise to inform the work of improving population health, the measurement of quality is seriously limited.

The committee discussed measures of quality in reference to the model, with measures including and related to the LHIs fitting largely under the Healthy Conditions (determinants of health and intermediate outcomes) and Healthy Outcomes headings. The committee focused on intermediate and ultimate outcomes because the specific process measures are too numerous and are dependent on the interventions actually implemented. Although the topic of health disparities is not explicitly identified in the logic model, the committee notes that inequities at the level of conditions that influence health are linked with disparities in health outcomes.

In response to the part of the charge requesting a discussion of alignment between the “the aims for improvement of quality in public health” (also known as “characteristics to guide public health practices”) and the measures of quality, the committee found that the characteristics of quality cannot be conceptually aligned with specific measures, since they describe the system as a whole, and refer to the public health system or interventions rather than quality measures per se. For example, measures of quality cannot be classified as vigilant or effective, but they can provide information about the existence of interventions or system capacity that demonstrate vigilance and effectiveness. The presence of a surveillance system (a resource or capacity), for example, may provide indication that the system is vigilant and effective. The six drivers of quality improvement in public health—metrics and information technology; evidence-based practices, research, and evaluation; systems thinking; sustainability and stewardship; policy; and workforce and education—also fit under Resources and Capacity. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. The Healthy Conditions segment of the model

also serves as a link to the ecological model6 describing the multiple determinants of health. An important caveat to consider in reviewing the logic model is that it is not intended to suggest a definitive classification system, but rather, a structured and coherent way to approach measurement of quality. The committee’s deliberations about the model and contents showed that assigning an item to one of the boxes is not necessarily straightforward or able to garner universal agreement. The categorization of health care was one area that required extensive discussion, and the committee reached agreement that health care access and quality fit in the Healthy Conditions segment, while the programs, policies, and services that are needed to have high-quality health care conditions belong in the Interventions box on the left. As a specific example, mammography screening programs, tobacco cessation services, and community education programs about healthy eating would go under Interventions, while mammography screening rates (women screened for breast cancer), persons receiving tobacco cessation services, and the proportion of population informed about the value of healthy eating would be classified as Healthy Conditions. There are programs, policies, and services related to all of the Healthy Conditions in the logic model. For example, for socioeconomic status, the programs and policies could include per capita funding for education and earned income tax credits. Environmental conditions result from programs and policies such as zoning policies, bike path funding, and safe routes to school. Health care “conditions” are a result of such policies and programs as health care reform, funding for community health centers, employer mandates, and clean air policies (i.e., to prevent asthma attacks in vulnerable groups). Health behaviors are influenced by such policies as drunk driving laws, seat belt laws, minimum purchase laws, and smoking bans.

Although Resources and Capacity is part of the logic model, the committee’s examination of measures of inputs was limited. One reason for this is the fact that these types of measures are more specific to the interventions selected and this level of detail is beyond the scope of a report such as this. Ongoing efforts exist to measure or verify aspects of a system that could contribute to making it high-performing (see IOM,

___________________

6 The ecological model is a diagram adapted from Whitehead and Dahlgren (1991) and used by IOM committees and HHS to show the array of determinants of health, or the ecology of health, beginning with individual level factors at the center (biology/genetics), then on to behavior, family, social networks, and communities, followed by broad policies pertaining to the determinants of health (education, income, etc.) at the state and national level (see HHS, 2013, and IOM, 2003a, p. 52).

2011a, for examples). The voluntary national effort of public health accreditation is one such effort (Public Health Accreditation Board, 2011).

The model can be used for several purposes. First, it illustrates the main steps in a process of health improvement: attention to resources and capacities, implementing interventions that work, achievement of intermediate outcomes (e.g., improvement in the conditions that influence health), and ultimate outcomes. Second, it helps illustrate that the quality characteristics (population-centered, equitable, proactive, health-promoting, risk-reducing, vigilant, transparent, effective, and efficient) refer to capacities and interventions, not to outcomes. For example, a health department with a robust injury surveillance system is demonstrating the quality characteristic “vigilant.” Regular reporting (e.g., annual) about a community unintentional injury data demonstrates “transparent.” Having the capacity to implement and then actually implementing evidence-based interventions to reduce injury in the community demonstrates a health department is population-centered and risk-reducing. Third, the logic model could be used to illustrate the relationships among different types of measures (as shown in the detailed logic models in Chapter 3). Fourth, the logic model can also inform thinking about the usefulness (e.g., applicability) and feasibility (e.g., availability of necessary data) of various kinds of measures at different levels of action— national, state, and local.

Under ideal circumstances the achievement of the highest possible health-related outcomes may be considered the ultimate indicator of a high-quality health (not health care) system. In practice, things are considerably more complex, both because of the lack of a singular sector or entity with the responsibility and the ability to improve the health of a population and because of the vast array of factors that influence health (e.g., the likelihood that a neighborhood with a very high socioeconomic level will have superior health outcomes by virtue of that fundamental characteristic, regardless of the presence of a competent health care delivery system or public health agency). One measure of health—life expectancy—has been tracked for a long time and is perhaps the most universally understood indicator of a nation’s health status.

Although they are not explicitly reflected in the LHIs, the foundation health measures of Healthy People 2020 reside in four domains:

- General health status (life expectancy, healthy life expectancy, years of potential life lost; physically and mentally unhealthy days; self-assessed health status; limitation of activity; chronic disease prevalence);

- Health-related quality of life and well-being (measures of physical, mental, and social health-related quality of life; well-being and satisfaction; participation in common activities);

- Determinants of health (biology, genetics, individual behavior, access to health services, and the environment in which people are born, live, learn, play, work, and age); and

- Disparities (measures of differences in health status associated with race and ethnicity, gender, physical and mental ability, and geography) (HHS, 2012).

Healthy People 2020’s overarching goals-longer, healthier lives; health equity; health-promoting environments for all; and the promotion of healthy life, development, and behaviors across the lifespan—acknowledge the importance of looking to population health outcomes to gauge the nation’s progress in meeting health objectives (HHS, 2008; Koh, 2010).

In a context of rapidly proliferating, duplicative, overlapping, and imperfect measures, the committee envisions a multisectoral health system in which

- All participant organizations define the quality of the system in terms of progress toward “long, healthy lives for all.”

- All participant organizations assess quality in the multisectoral health system via a well-constructed portfolio of measures spanning the resources available, the interventions (programs, policies, etc.), the conditions in which people live (referring broadly to all the determinants of health including behavior and the social environment), and the health outcomes (see Figure 1-1; see Recommendation 2-1 for the description of a well-constructed portfolio).

- Communities report about their overall public health quality annually and use specific measures regularly for the purpose of improving outcomes.

The committee reviewed the IOM report Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001) and its recommendation made to all components of the health care delivery system. In the same spirit of mobilizing partners around improving quality, the present committee makes an analogous recommendation pertaining to quality in the health system writ large.

RECOMMENDATION 1-1: All partners in the multi-sectoral health system should adopt as their explicit purpose to continually improve health outcomes of the entire population and the conditions in which people can be healthy. The extent to which this purpose is achieved reflects the overall quality of the health system.

To help in achieving this recommendation, this report outlines selection criteria and provides sample metrics to support HHS and its partners in enhancing quality to ultimately improve population health.

The intersection of quality improvement and the Healthy People 2020 effort in HHS, against the backdrop of health care reform and growing interest in population health concepts make this a time of great opportunity to create platforms on which public health and health care can begin to use same language, employ some of the same metrics, and work together to bring about the shared goal of long, healthy lives for all.