In this chapter, the committee discusses the use of measures of quality in the context of the implementation of Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions such as the call for establishing accountable care organizations (ACOs) and changes in community-benefit requirements for nonprofit hospitals; the evolution in public health practice (e.g., a national accreditation movement); the diffusion of the concept of population health within the health care delivery system; and fiscal constraints that motivate the drive to demonstrate quality in terms of value realized on investment. The chapter’s primary focus on health care and public health is not intended to suggest that there are no other stakeholders. It is a reflection of the most obvious locus for collaboration to improve the health of communities, and of common ground, such as the fact that many health departments provide clinical care services, and the fact that several provisions of the ACA offer further opportunities for health care delivery and public health practice to “meet in the middle” (see, for example, Stoto [2013]).

When applying the Public Health Quality Forum’s definition of quality, particularly the notion of “conditions in which the population can be healthy,” to the Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicators (LHIs), it is clear that quality in non-health sectors matters in improving population health. Although the committee was not constituted to examine in detail issues related to measurement in non-health fields, the committee believes that the selection criteria and measures of quality discussed in this report may have broader usefulness, such as to schools, community development financial institutions, and non-health government agencies. Other entities that work in the population health improvement “space” but that may not have health as a primary objective could find measures helpful in documenting co-benefits—for example, areas where improve-

ment in health has been associated with improvements in school performance, or where community development and health have strengthened one another. One high-profile example can be found at the intersection of climate change and environmental quality, where policy changes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions can improve air quality, thus improving health outcomes (lower-respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality) (see, for example, Haines et al., 2009). Another example is the way in which improving the quality of the educational system may be a contributor to increased high school graduation rates (LHI AH-5.11), which, in turn, may have positive health effects. Also, communities where cross-sector coalitions work to improve health (while achieving other socially valuable objectives) may wish to consider a small number of health-oriented measures as a way to measure quality of the collaborative efforts to improve health while strengthening public transit or facilitating healthful community development. A municipality could, for example, report annually on its cross-sector efforts to improve health, using metrics that, like high school graduation rates, go beyond health outcomes and track dimensions of the environment that are known to have health effects. As outlined in the 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future, the United States obtains low value from its health care delivery system, which is exceptionally high-cost and achieves relatively poor health outcomes compared to other high-income countries. Health care costs have been rising steeply for some time, although a slight slowdown was reported in early 2013 (Cutler and Sahni, 2013; Ryu et al., 2013; Stremikis et al., 2011). Earlier IOM reports have explained how a multisectoral health system can improve population health and increase the value realized on the nation’s investment (IOM, 2011a, 2012). The engagement of many sectors is essential to address the well-described multifactorial causes of poor health at the population level (Remington and Booske, 2011). Speakers at the committee’s December 2012 information-gathering meeting motivated the committee to focus on the relationship between health care and pub-

___________________

1 The complete list of Healthy People 2020 objectives and approximately 1,200 measures is available from the Healthy People website. Measures are denoted by an acronym for the given Healthy People 2020 topic (e.g., AH denotes Adolescent Health) and are numbered sequentially according to topic and objective (e.g., AH-5.1, where objective 5 in the topic of Adolescent Health is “increase educational achievement” and measure 5.1 is “Increase the proportion of students who graduate with a regular diploma 4 years after starting 9th grade.” The complete list of objectives and measures is available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HP2020objectives.pdf (accessed March 4, 2013).

lic health as central among other potential linkages and partnerships for improving population health (see Appendix C). Although recognizing the importance of other stakeholders in the health system, the committee was guided by this central relationship in outlining the uses of quality measures.

There are a growing number of opportunities to use measures of quality. Healthy People 2020 is directed at the country’s entire health enterprise—not merely at governmental public health agencies, but also at health care delivery organizations at all levels, at community-based organizations involved in health improvement, at the business community, at government agencies working in areas relevant to health (e.g., transportation and education) and at many others who contribute in the broadly conceptualized health system described in Chapter 1. The concept of multiple determinants of health was central in the development of Healthy People 2020 and is reflected in a small way in the 26 LHIs, as some of them are in the purview of health care delivery system, while others (high school graduation rates, depression in adolescents, air quality) are influenced by a wider array of actors, including health departments, schools, community-based organizations, the business sector, and many others.

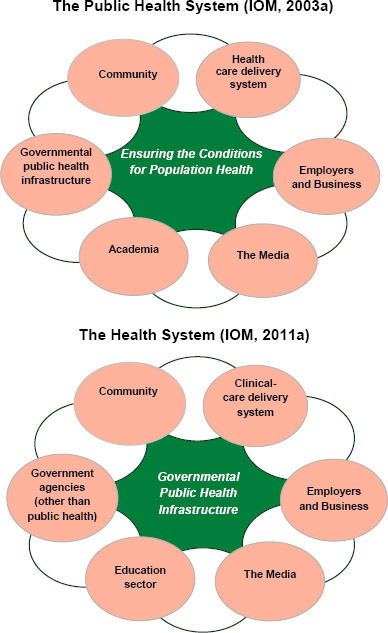

In describing the uses and users of measures of quality, it is important to clarify some key concepts. The starting point is the concept of “total population” defined by Jacobson and Teutsch (2012) as all persons living within a geopolitical area;2 this is in contrast to more limited sub-populations, such as the enrollees in a health plan or the patients of a provider. The notion of a system-within-a-system may be useful here, as health care delivery systems, the education system, employer systems, and other systems can be thought of as subsystems, each with its own subpopulation, all of which contribute to total population health. Finally, the distinction between governmental public health infrastructure and the multisectoral health system discussed in Chapter 1 is further illustrated in Figure 4-1. The 2011 IOM report For the Public’s Health: The Role of Measurement in Action and Accountability updated the work of an earlier IOM committee to create an illustration of government public health as one of many actors contributing to a broader system of assurance for

___________________

2 Jacobson and Teutsch (2012) recommend that “the concept and definition of ‘total population’ and ‘total population health’ across a specified geopolitical area should be used when setting goals and objectives for improving overall health status and health outcomes of interest to the clinical care system, the government public health system, and stakeholder organizations” (p. 11).

FIGURE 4-1 The multisectoral health system. SOURCES: IOM, 2003a, 2011a.

population health. The revised illustration, shown in Figure 4-1, places governmental public health infrastructure at the center of the process for

population health improvement in acknowledgment of the special responsibility and qualifications of public health agencies in general. However, there are limitations to other stakeholders’ ability or willingness to engage, and this illustration reflects an aspiration and not always the reality of the actual functioning of the public health agency as convener, steward of the community’s health, knowledge generator and disseminator, and adviser or catalyst in mobilizing to improve health (IOM, 2012).

Viewed through the expansive lens just described, there are many potential users of measures of quality. In addition to governmental public health agencies and communities, health-focused nonprofit and community-based organizations, hospitals and health care systems, ACOs, managed care organizations and payers, and patient-centered medical homes and physician practices all seek the same outcome: to achieve longer, healthier lives for all individuals and populations. The committee hopes that the measure selection criteria and suggested measures of quality in this report will prove to be a useful guide to all who work to improve population health—and especially those who do so in collaboration.

There are numerous recent developments that create opportunities for collaboration that is informed by measures of quality. These developments include the ACA provision that revised the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS’s) requirements for tax-exempt hospitals to include conducting a community health needs assessment, the ACA’s promotion of accountable care organizations as a governance tool for coordinated and high-quality care, the growing influence of the Three-Part Aim framework, and the creation of a national public health accreditation program that requires state and local public health agencies to conduct health needs assessments and develop improvement plans.

The committee has identified some of the primary users and purposes for the quality measures. Measures can be used (1) by governmental public health agencies; (2) by nonprofit hospitals, ACOs, and other health care entities; (3) by community organizations, philanthropies, and others in their measurement and quality improvement efforts; and (4) for expanding the understanding of the Three-Part Aim. As previously discussed, measures can be used for three purposes:

- Assessment: providing a snapshot in time, such as community health needs assessments or benchmarking (for the purpose of public reporting, ranking, comparisons, etc.).

- Improvement: requiring measurement over time, such as assessing progress toward goals in community health improvement efforts.

- Accountability: demonstrating that investments have been used effectively and efficiently to deliver results (healthy outcomes).

The committee recognizes that these different uses involve somewhat different requirements for data collection and reporting. The present report and chapter focus largely on the use of measures for quality improvement in response to the charge given by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

USE BY GOVERNMENTAL PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCIES

Community health assessments (CHAs) are frequently conducted by public health agencies as part of their community health improvement processes, or in response to state law. CHAs ideally emerge from a community process and are based on knowing which interventions work and how well they work, and they need to be paired with improvement plans in order to address the issues identified. Community health improvement planning is a common activity of local and state health departments, and a quick search of the Web results in hundreds of examples of community health improvement plans developed by an array of jurisdictions and organizations. The National Association for County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) has supported such activities for decades, developing and refining assessment tools such as the Assessment Protocol for Excellence in Public Health (APEX PH) and more recently Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) (NACCHO, 2007).

Conducting CHAs is a prerequisite for state and local public health agencies to initiate national voluntary accreditation by the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB). The development of community and state health improvement plans is another prerequisite for public health accreditation. PHAB was formed to implement and oversee national accreditation of public health departments, with goals that include “to promote high performance and continuous quality improvement” (PHAB, 2011). The first major domain of the accreditation process is assessment, which includes systematic monitoring of health status; the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data; the use of data to inform public health policies, processes, and interventions; and participation in a process for the development of a shared, comprehensive health assessment of the community.

The MAPP tool developed by NACCHO and used by many local health departments includes a four-part process:

- Community themes and strengths assessment

- The local public health system assessment

- The community health status assessment

- The “forces of change” assessment

A specific application of MAPP is the Community Balanced Scorecard (CBSC) which is a strategic planning process to focus on priority public health outcomes. CBSC can improve the use of MAPP assessments, making MAPP strategies and plans better focused. These processes reinforce the role of governmental public health agencies in leading the assessment of the health of the public for a given community. A robust set of measures of quality provide a solid foundation for these activities.

The Missouri Information for Community Assessment Priority Setting Model (MICA) illustrates one way to prioritize the implementation of a community health improvement plan and “is intended to provide high-level consideration of the diseases or risk factors that are most important to a community” (Simoes et al., 2006). MICA uses data from vital records, hospital discharge records, emergency departments, risk factors from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, and eight epidemiologic measures to construct six criteria for setting priorities for community action: size, severity, urgency, preventability, community support, and racial disparity. More recent efforts for planning and prioritization have been undertaken using America’s Health Rankings for data at the state level and the County Health Rankings at the county level.

The committee views the nine characteristics of quality in public health identified by the HHS Public Health Quality Forum as a guide for state and community health improvement plans and their implementation. The committee also notes that there is considerable overlap between these nine aims or characteristics and the six improvement aims outlined for health care in the IOM’s (2001) Crossing the Quality Chasm report. Communicating about this and other areas of convergence could help inform and facilitate joint population health improvement efforts involving health care and public health entities.

Assessment and planning are necessary, but not sufficient for improvement. Furthermore, the complex problems that top the list of priorities identified in most health assessments, such as tobacco use and obesity, cannot be addressed by health departments alone, and, in addition, those agencies do not have sufficient resources to address these issues on their own (IOM, 2012). One promising opportunity for partnership has been created by the revised community benefit obligation of tax-exempt hospitals, which are required to address community needs

identified in their newly required community health needs assessments (CHNAs). In the context of existing or new collaborative needs assessment efforts, hospitals can contribute ideas, strategies, and resources (including funding and data).

USE BY NONPROFIT HOSPITALS AND OTHER HEALTH CARE INSTITUTIONS

According to the IRS, “providing community benefit is required for hospitals to be tax-exempt charitable organizations under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.” Community benefit requirements for tax-exempt hospitals call on institutions to be “transparent, concrete, measurable, and both responsive and accountable to identified community need” (HHS, 2011). Young and colleagues (2013) have shown that hospitals have often used the community benefit requirement to cover uncompensated care, pay for training, and perform other such activities, some of which provide little or very narrowly defined benefits to communities. To accomplish a transformation in the implementation of community benefit requirements, the ACA requires tax-exempt hospitals to conduct a CHNA and to adopt and use an “implementation strategy.” Hospitals are required to make the CHNA “widely available to the public” and to report to the IRS on the activities undertaken to respond to the needs identified in the CHNA. Rosenbaum and Margulies (2011), Trust for America’s Health (2013), and others have commented on the opportunities afforded by the ACA amendment to the Internal Revenue Code, but they have also called for more specific requirements from the IRS to clarify what is expected of hospitals. One challenge has been the fact that the original regulations ask that hospitals include public health expertise in the assessment, but there was no requirement for hospitals to work with their local public health agency. One potential leverage point is the role of states in cases where the state health agency provides hospitals with certificates of need, in which case the state agency could require that the hospital collaborate with the local public health agency. Nevertheless, this IRS requirement has tremendous potential to facilitate collaboration in the multisectoral health system, and especially between public health and clinical care, to improve population health. Such collaborations can benefit from the framework provided by the Three-Part Aim described later in this chapter.

There are many examples of hospitals contributing to improving population health. Nonprofit hospitals in San Francisco, for example, have been collaborating with the health department for nearly two dec-

ades, have been reporting on their community benefit through a shared website since 2007, and have been contributing to the San Francisco Community Health Improvement Plan, due to be completed in 2013. Collaborative efforts have also engaged business and community organizations, and currently the city-wide coalition among hospitals, the public health agency, and other partners is working to “increase healthy living environments, increase healthy eating and physical activity, and increase access to high quality health care and services” (RWJF, 2012). The coalition website provides access to “Community Vital Signs, which makes use of more than 30 data indicators and has set 10 priority health goals that will be measured every year to track their progress” (RWJF, 2012). In another example, Boston Children’s Hospital uses nurse practitioners and community health workers to conduct home visits of asthma patients and help identify and remove asthma triggers that are present in the home (Boston Children’s Hospital, 2013). The program has resulted in savings in health care costs from decreased emergency room visits, and the hospital has been working with the state Medicaid organization and other payers to develop a payment system for this type of comprehensive preventive approach. Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus provides another example of a hospital’s community benefits, which it achieves through its “Healthy Neighborhoods, Healthy Families (HNHF), a partnership with the city and community-based organizations to address affordable housing, healthy food access, education, safe and accessible neighborhoods, and workforce and economic development” (Prevention Institute, 2013). The hospital’s efforts have contributed seed funding and a partnership with a community development nonprofit organization that led to the addition of more than 100 affordable and revitalized homes to the community (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 2012).

The data resources and overall approach used by nonprofit hospitals to conduct the required CHNA have become more available in a consensus format through www.chna.org (hosted by www.communitycommons.org), “a free Web-based platform designed to assist nonprofit organizations, state and local health departments, financial institutions, and other organizations seeking to better understand the needs and assets of their communities, and to collaborate to make measurable improvements in community health and well-being” (Community Commons, 2013). These resources, which include advanced mapping and analysis technology, have been developed as a result of broad consensus of hospital, public health, and community organizations. The committee believes that the process for selecting measures of quality described in this report could prove useful to the process of developing CHNA by providing

guidance on the most important things to measure everywhere, and the measures will likely add value for improvement efforts emerging from those assessments.

In addition to the new IRS community benefit requirements, the reforms initiated by the ACA include certification of ACOs under Medicare, which can serve as another potential leverage point or vehicle for engaging hospitals and other health care organizations with public health agencies. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) defines ACOs as groups of providers that come together to provide well-coordinated and high-quality care to Medicare beneficiaries. CMS has established incentive mechanisms for ACOs, such as the Medicare Shared Savings program that includes 33 required quality measures, 8 of which relate to clinical prevention, and most of which coincide with LHIs (RTI International and Telligen, 2011). There is little consensus about the extent to which ACOs should be truly accountable for total population health, that is, for the health of all individuals residing in a geopolitical area rather than just for chronic disease management for the enrollees in the ACO (Noble and Casalino, 2013). As one example, the Accountable Care Community of Akron, Ohio, described itself as having a community-wide focus (Austen BioInnovation Institute, 2012).

The committee believes that the notion of accountability for improving total population health appeals to more than just health departments. It is congruent with efforts in the health care delivery sector, including more expansive thinking about mechanisms to engage a broader range of stakeholders in population health improvement. Magnan and colleagues (2012) have described accountable health communities as voluntary regional organizations that focus on health in addition to health care, and that engage local stakeholders, including hospitals, health departments, and community organizations in the collection of data, the setting of goals, the facilitation of system reforms, and the demonstration of proper stewardship of financial resources, including investing in the social and environmental determinants of health. Magnan and colleagues (2012) called for the creation of health outcomes trusts, which would build on existing coalitions, and function as the heart of the accountable health community. The trusts would work with state and local health departments to evaluate measures of health and health care—an effort that would be facilitated by having standardized measures of quality from which to draw.

Some community health improvement efforts are driven by a partnership between health care, public health entities, and entities from other sectors, such as academic institutions. Examples can be found across

the country, from Sonoma County, California, to Akron, Ohio.3 Many such collaborations use websites to engage stakeholders and to share information with communities, including community health needs assessments conducted jointly, hospital community benefit plans, health department reports, and other materials.

USE IN EXPANDING AND UNDERSTANDING THE THREE-PART AIM

As indicated in Chapter 1, the Triple Aim concept developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has not only become an important framework in the U.S. health care delivery system, but it also has been adapted for use in CMS and more broadly in HHS as the Three-Part Aim, including as a framework for the National Quality Strategy.

The Three-Part Aim framework—better care/quality, lower costs, and improved population health—provides an ideal platform for health care and public health collaboration since it is familiar to health care audiences and includes an aim to improve population health. IHI continues to work with dozens of new communities using the related Triple Aim approach. This is likely to generate a rich array of information, including, potentially, innovative approaches that can be disseminated widely across health care settings.

The IHI paper “Measuring the Triple Aim” (Stiefel and Nolan, 2012) discusses measurement for all three dimensions of the Triple Aim including population health. However, the population health measurement component emphasizes primarily clinical measures. Although the model of population health and the corresponding analytic framework used in the IHI paper includes an adaptation of the Evans and Stoddart (1990) model of the social determinants of health, the authors acknowledge that necessary and robust measures for some nonclinical factors are not readily available. This observation echoes some of the findings of the National Quality Forum (NQF) Population Health Endorsement Maintenance Steering Committee that attempted to identify and endorse population health measures as part of the larger NQF process and faced considerable limitations and challenges in its work (Jarris and Stange, 2012).

The committee believes that there is an important opportunity for the quality measures discussed in this present report to augment measure-

___________________

3 Examples can be found at http://www.healthysonoma.org and http://www.sonomahealthaction.org (accessed June 27, 2013).

ments of the population health component of the Three-Part Aim and to expand the use of that framework.

Specific examples of the use of quality measures in initiatives that are implementing the Three-Part Aim need to be studied and the best practices need to be shared. The example of Sonoma County in California shows how a public health agency can assemble a full spectrum of health status, health behavior, and social determinants data to support an initiative in that community. Such examples can serve as important precedent for future Triple Aim or Three-Part Aim projects.

The committee believes that future success in moving the LHIs depends on the extent to which they can be incorporated into Three-Part Aim initiatives and become used by all organizations that use the Three-Part Aim. An essential first step will be to reach out to key measurement experts as well as groups that have worked on population health improvement as part of a Three-Part Aim initiative and to build on the work and learning to date. In this future work, the focus can be to provide reliable and accessible data sources to inform measures of quality.

Finding 4-1: The committee finds that the concept of a Three-Part Aim described in the National Quality Strategy could play a growing and important role in the process of establishing population health as an essential area of focus in transforming health care and health in the United States. The committee also finds that additional development is needed by users of the Three-Part Aim to incorporate evidence-based measures representing social and environmental determinants of health, equity, and the concept of total population health.

The potential of the Three-Part Aim as a transformative concept could be strengthened if government public health agencies are able to perform the role of conveners and facilitators of stakeholders and advisers in ensuring that community health (needs) assessments are conducted from a total population perspective. Health departments do not always have the structure, size, resources, and capabilities required to rise to the challenge, and potential solutions have been discussed elsewhere (including in IOM, 2011a,b, 2012).

RECOMMENDATION 4-1: The committee recommends that the Department of Health and Human Services convene stakeholders to facilitate the use of measures of quality for the multisectoral health system and their integration into all appropriate activities under the Three-Part Aim with a special focus on the social and environmental determinants, equity, and the concept of total population health.

Areas where measures of quality could be integrated in HHS activities include CMS Innovation Center grant programs, Medicare requirements for ACOs, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) programs such as Community Transformation Grants.

KEY REQUIREMENTS FOR USING QUALITY MEASURES FOR IMPROVING POPULATION HEALTH

The committee recognizes that in many ways the use of measures of quality in order to improve population health is still in its infancy. The committee reviewed the NQF Guidance for Evaluating the Evidence Related to the Focus of Quality Measurement and Importance to Measure and Report (2011), the “Measuring the Triple Aim” white paper from IHI (Stiefel and Nolan, 2012), and the criteria developed by the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020 (HHS, 2008). The committee also invited several speakers to share lessons learned from state and national population health improvement efforts (see Appendix C). Ultimately, the committee identified a number of criteria for measures used for the purpose of population health improvement. Some measures currently in use do not meet all the criteria, and this report has outlined a vision for better measures for supporting improvement efforts aimed at population health.

Later in this chapter, the committee provides a brief discussion of some key requirements for the measurement enterprise from the perspective of end users in public health, health care, and other settings. Requirements include local relevance of quality measures (which has time and availability components) and equity, as a guiding principle for all measurement and quality improvement efforts. As an example of the importance of local relevance, a community partnership implementing strategies to reduce childhood obesity would seek to measure the impact of those strategies on obesity prevalence as soon as possible. However, timeliness in measuring such improvement in population health is generally not realistic with existing data sources. Closely related to the need

for timeliness is the need for quality measures of processes that are directly linked to the interventions being used to improve population health. Such measures provide more timely feedback than is usually possible with outcome measures. They also help teams and coalitions assess the effectiveness of their implementation. A comprehensive list of process measures is beyond the scope of this committee’s work; however, it is important to have such a set of measures tied to evidence-based interventions, while recognizing that at a local level other, more specific measures might also be needed. The number of potential measures is enormous and a top-down approach by a national group would likely generate measures that are of limited benefit to actual circumstances at the practice level. A better approach would be to have a system managed by a national entity harvest good process measures, and evaluate and endorse useful measures generated by frontline improvement efforts of demonstrated effectiveness. However, over time, improvement teams and coalitions could develop measures in areas where there are gaps, test and use such measures, and then submit successful measures to an independent body for consideration and endorsement for broad use, as suggested in Recommendation 2-3.

Another important requirement for quality measures to improve population health is to measure equity by examining health disparities and changes in disparities. This is critical for two reasons. First, many groups attempting to improve population health will explicitly try to reduce disparities, widely accepted as an important health objective in the United States. In addition, even when not attempting to reduce disparities directly, they will need to ensure that they are not worsening disparities while working to improve the health of the overall population. In other words, they would use measures of equity as a “balancing measure,” to avoid improving some aspects of a system at the expense of others (Randolph et al., 2009). Thus, teams and coalitions using quality measures for improvement will need to stratify key measures for vulnerable subpopulations, and they will need to have data available that allow stratification.

Quality measures used to improve population health must be available at the national, state, and local levels. The committee recognizes that having data available for quality measures at the local level is the biggest challenge and, not surprisingly, is where the greatest gaps lie. Given the obvious centrality of the local community in public health and clinical practice, and given the fact that most improvement efforts will involve implementation at the local level, the committee’s search included the guidelines provided in the University of Kansas Community Tool Box for selecting community-level indicators (University of Kansas, 2013). In

addition to the characteristics common to any indicators, such as being statistically measurable, logical or scientifically defensible, and reliable, the developers of the tool box added other characteristics: policy relevant, reflective of community values, and attractive to the local media.

USING MEASURES OF QUALITY BEYOND THE HEALTH SECTOR

The committee has provided examples of the potential use of measures of quality by health care and public health organizations, but applications of quality measures could extend to philanthropic organizations, business, and non-health government organizations. The processes required for identifying and using measures of quality for assessment, improvement, and accountability may be convened by an “integrator,” which is “an entity that serves a convening role and works intentionally and systemically across various sectors to achieve improvements in health and well-being for an entire population in a specific geographic area. Examples of integrators range from integrated health systems and quasi-governmental agencies to community-based non-profits and coalitions” (Chang, 2012). The engagement of non-health stakeholders in efforts to improve health (along with achieving other, primary objectives) has expanded greatly in recent years. Examples from the public sector include the ACA-established National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council, which brings together multiple cabinet secretaries and agency heads under the leadership of the Surgeon General, and “health-in-all-policies” efforts such as the joint Sustainable Communities Initiative of the Department Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Transportation, and the Environmental Protection Agency.

A strong knowledge base makes it possible to document the complex and multiple relationships between socioeconomic determinants and health outcomes, and between factors in the built environment and health. Understanding these relationships, and increasingly, some of the interventions that can influence them, requires common ways to measure and report progress. This provides further rationale for community health assessment (and the use of measures of quality as part of such assessments). Various aspects of the built environment—including housing, the accessibility of food and other essential items, opportunities for community entrepreneurs, and the availability of green spaces—are important factors that influence health outcomes, but actions on these factors take place outside the public health and health care sectors. The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), which is intended to encourage banking insti-

tutions to help meet the credit needs of the communities in which they operate, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, offers additional uses for community health needs assessments. The CRA regulation contains an option for banks and community development financial institutions to develop a plan with community input detailing how the institution proposes to meet its CRA obligation. The plan is tailored to the needs of the community using direct community input at the development stage, where health care and health concerns can be a major focus. The committee believes that financial institutions can use measures of quality to focus on improving total population health as one of their objectives in community development. The Federal Reserve has been engaged in development efforts, including enhancing the food environment, improving neighborhoods by bringing in small businesses, and strengthening public transit to increase access to employment and other necessities, with a secondary benefit of increased physical activity (as evidence indicates that public transit is linked with more walking) (Erickson and Andrews, 2011).

Investing in What Works for America’s Communities: Essays on People, Place & Purpose showcases and discusses the innovations that can be harnessed to transform struggling communities (Andrews and Erickson, 2012, p. 378). The authors describe an approach to community development that is

focused on leadership that is able to promote a compelling vision of success for an entire community, marshal the necessary resources, and lead people in an integrated way. It must be accountable for outcomes, not just specific outputs (such as the number of apartments built). The outcome goals for the entire community should be bold: doubling the high school graduation rate, halving the number of people living below the poverty line, cutting emergency room visits by 75 percent, or making sure 100 percent of kindergarteners arrive at school ready to learn.

In another example, the Community Development Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco conducts a Community Indicators Project “to collect input from community development professionals about the issues and trends facing low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities in the 12th District” (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2013). Health was identified as the ninth out of nine top issues, but some of the other issues are linked with the social determinants of health, including household financial stability, the housing market,

and employment conditions. It is unclear whether this Federal Reserve project is being used as part of a broader effort to measure and document improvement, but it provides a possible locus for the use of measures of quality to assess the effects of community development efforts on population health improvement.

The United States currently receives poor value from its health system, whose investments are largely in the clinical realm. Unsustainably high cost and mediocre outcomes constitute a dual challenge that is having a growing effect on U.S. health and wealth (Johnson, 2012; NRC and IOM, 2013; World Economic Forum, 2008). Substantial progress in improving population health is needed, and quality measures can help public health departments, health care organizations, communities, and many others to work collaboratively to maximize strengths and begin to alter the conditions for health.

It will also be important for HHS and other stakeholders to promote the use of a unified portfolio of measures with the characteristics described in Recommendation 2-1, and that would emerge from the endorsement process across the country and in a range of settings including the clinic and the community. There are specific challenges that need to be addressed first, most notably making timely data available at the local level and identifying better process measures for local use. Addressing these needs as well as taking advantage of the numerous extant and emerging opportunities for multisectoral engagement to improve population health will be vital to the nation’s health and well-being for many decades to come.