Neurobiological, Psychological, and Social Development

Important Points Made by the Speakers

- Brain regions show changes after adolescence that may be related to the needs of young adults and the skills they are developing. Neurobiological changes during the young adult years are not necessarily just a continuation or completion of adolescent brain development; there appear to be some distinct organization developments. (Luna)

- Changes observed in the demography of young adulthood do not necessarily imply that the psychology of young adults has changed. (Steinberg)

- Young adulthood is more about the development of interdependence than about the development of independence. (Settersten)

Adolescence and young adulthood form a continuum for many development processes, but there are also unique aspects of young adulthood. Three speakers at the workshop described these discontinuities and continuities in the areas of neurobiological, psychological, and social development.

Scientists who study brain development have spent much more time looking at adolescents than at young adults, said Beatriz Luna, professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh. By the time people become young adults, significant aspects of their neurobiology have reached adult levels. However, their brains also continue to change, in part because of continuing brain development, and in part because “behavior is always remodeling the brain.”

Brain plasticity is evident throughout the lifespan, Luna said, but different kinds of plasticity come to the fore at different stages. For example, from childhood through adulthood, the gray matter in the brain, which contains neurons, thins as it loses synaptic connections (Gogtay et al., 2004). This is a good thing, said Luna, because it is the method the brain uses to “sculpt itself to its particular environment.” Few studies of this process have looked at people older than 21. However, studies of particular brain regions show continued changes after adolescence. For example, the basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex undergo a protracted maturation process (Sowell et al., 1999). The neurotransmitter dopamine in these parts of the brain peaks during adolescence, but remains high in young adults before declining later in life (Luciana et al., 2010).

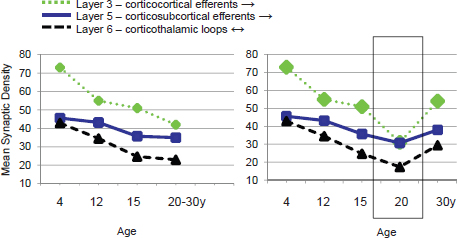

In another study, the synaptic density in the prefrontal cortex declined through adolescence, but increased between the ages of 20 and 30, according to an analysis by Luna based on data from Huttenlocher and Dabholkar (1997), illustrated in Figure 2-1. This could reflect a shift in the way the young adult brain is being affected by the environment, she said.

Pathways that connect different parts of the brain also change over time. For example, the superior longitudinal fasciculus, which is involved in cognition and executive function, continues to develop throughout the young adult years, which may reflect the greater ability of young adults to make decisions compared with adolescents. Other connectors involved in cognition, the emotional aspects of behavior, impulse control, and the ability to monitor performance and make corrections after errors also continue to mature during young adulthood.

Adolescents have greater brain reactivity to rewards than do young adults, perhaps because of novelty seeking (Chein et al., 2011). During adolescence, the ability to integrate the perspectives of others is reduced (Burnett et al., 2009). Adults are better able to dampen reward reactivity, including peer-related rewards, and they demonstrate greater engagement of executive reward processing. In addition, from adolescence to adulthood, the ability to assess another person’s emotions increases (Hare et al., 2008). Brain development that supports habit forming and learning peaks in adolescence, and by young adulthood habits are more established.

FIGURE 2-1 The density of synapses in some layers of the prefrontal cortex declines during adolescence, but increases again in young adults.

NOTE: Mean synaptic density in synapses/100 μm3 by cortical layer.

SOURCE: Luna, 2013, created from data from Huttenlocher and Dabholkar, 1997.

Stages of brain development should not be seen simply as impaired versions of the adult brain, Luna concluded. Rather, these stages are suited to what is needed during that period. In that respect, the continued maturation of social and emotional processing in young adults may support a shift in the pursuit of long-term life goals. When “I talk to my kids, 20 and 22, they are really starting to think about this in a way that they never had before. What am I going to be when I grow up?” Luna said.

Little is known about normative psychological development during young adulthood, said Laurence Steinberg, Laura H. Carnell Professor of Psychology at Temple University. Sociological observations show that young adults take more pathways through this period of life than have earlier cohorts of young adults, but sociological observations should not be conflated with psychological hypotheses. “We don’t know … whether these changes in the normative timetable of moving into the roles of adulthood are affecting the psychological development of people in this age period, or whether there is something special about psychological development in the current generation of people in this age period that is affecting the timetable.” For example, a common hypothesis is that greater economic dependence of young adults on their parents has delayed their progression to employment, marriage, and family formation and has “stunted” their

psychological development. However, whether this is true is unknown, said Steinberg. In fact, a countervailing piece of evidence is that the attitudes toward self of young adults have changed little over time despite these sociological changes. “We need to resist jumping to the conclusion that just because the demography of young adulthood has changed, the psychology of young adulthood has changed,” Steinberg said. “I am not persuaded that today’s 25-year-olds are any different psychologically than their parents were when they were 25, even though their life circumstances may be very different.”

One complication is that the diversity in experiences following high school may make drawing meaningful generalizations nearly impossible. Though adolescents undergo many of the same experiences, young adults have great differences in education, employment, relationships, and so on. “It is going to be more difficult to come up with a general theory of psychological development during young adulthood that is going to apply across the population than it is to come up with a theory about psychological development during adolescence,” said Steinberg.

Some general observations are possible, Steinberg observed. As Luna mentioned, executive function, impulse control, planning, and related aspects of psychological functioning continue to mature in young adulthood. Young adults take longer to think about hard problems before taking action, as opposed to easier problems, than do adolescents (Steinberg et al., 2009). They also are less sensitive to rewards, again as noted by Luna, and are more sensitive to costs (Cauffman et al., 2010). Young adults show a decrease over time in risk taking compared with adolescents, as demonstrated by their rates of being involved in violent crime, automobile crashes, unintentional drownings, nonfatal self-inflicted injuries, onset of illicit drug abuse or dependence, and unintended pregnancies, all of which decline over the course of the young adult years. These declines appear to be related to “improvements in impulse control and a diminishment in reward sensitivity,” Steinberg said, so that young adults “do not engage in sensation seeking quite as much.”

Late adolescence and young adulthood is the most common age for the onset of major psychiatric disorders (Paus et al., 2008). “Almost no serious psychiatric disorders … have their age onset before age 10. [And] if you can live until 25 without having a serious psychiatric disorder, you are very unlikely ever to have one,” said Steinberg. Given this heightened risk, greater attention needs to be devoted to the needs of this population for mental health services, Steinberg said. Also, brain plasticity cuts both ways. Positive experiences can foster positive brain development, but negative experiences such as exposure to trauma and stress can affect the development of prefrontal systems in ways that may not be manifested until later in life.

The psychosocial research agenda has shifted, Steinberg concluded. In

the past, a major focus of research on young adults was their development of identity and intimacy through milestones such as employment, marriage, and family formation. Sociological changes have pushed these tasks to later in life for many young adults (even as the average age of puberty has decreased, as Steinberg noted in response to a question during the discussion period). The more relevant issues today are changes in role demands such as extended schooling, delayed entrance into career employment, and delayed marriage. These changes call for greater attention to the development of self-regulatory competence, the ability to function successfully, and the renegotiation of relationships with parents.

The social landscape of early adult life has been radically transformed in recent years, said Richard Settersten, Jr., professor of social and behavioral health sciences at Oregon State University. Demographers and sociologists have been studying the major transitions of young adulthood for decades, which has yielded important insights into the challenges and opportunities of becoming an adult today, how experiences vary across populations, and how the process has changed over time (for foundational research, see Berlin et al., 2010; Danziger and Rouse, 2010; Osgood et al., 2005; Settersten, 2012; Settersten and Ray, 2010a,b; Settersten et al., 2005; Waters et al., 2011).

Public attention has focused on the large and growing numbers of young adults living at home. However, young adults have widely varying living arrangements, only some of which involve coresidence with parents. The more important historical shift in the living arrangements of young adults, Settersten asserted, is that this period of life no longer involves a spouse. Also, living at home is not a new thing. Rather, the recent recession has exacerbated a trend toward coresidence with parents that extends back to the early 1980s. This broader trend appears to reflect changes in both children and their parents. New kinds of parents have brought about new kinds of children, and parent-child relationships have become closer and more connected. Parents and children are renegotiating their relationships anew as children become young adults. Indeed, such renegotiations are occurring at the other end of life too, between middle-aged children and their own aging parents. What it means to be a “child” and a “parent” are being revised in every period of life.

For many young people, living at home can actually be a smart decision, Settersten said. Young adults living at home can devote their time and resources to education, take low-pay or no-pay internships and apprenticeships to build skills, or create a nest egg that gives them a stronger launch when they do leave home. Moreover, living at home keeps many

young adults out of poverty. Because “adulthood” is equated with “independence” in the United States, and being “independent” means not living at home, there are growing concerns about young adults who live at home longer or return home later on. However, in other countries where rates of coresidence are high, we do not see the same concerns.

The young adult years also involve the pursuit of higher education, which is generally needed to achieve a decent standard of living. Yet, greater rates of college going have generated concerns about retention, graduation, and the accumulation of debt, especially among young people who already are the most vulnerable. Declining wages for many jobs exacerbate concerns about debts incurred from education. These are important topics that need further study, said Settersten.

Securing a full-time job and living independently, takes longer today, along with raising a family. Young adults also are having a much greater range of employment experiences getting to a full-time job. The recession has not created a new set of problems; it has heightened a set of existing problems that young people have been experiencing for some time. Hard economic times have brought attention to these problems and also offered a culturally acceptable explanation for young people and their parents to rationalize their circumstances.

Marriage and parenting now come significantly later in life. Today, marriage and parenting culminate the process of becoming adults rather than starting adulthood. The delay in marriage and parenting has dramatically changed the nature of young adulthood by freeing up years in which people now actually live more, not less, independently. How the young adult years are experienced is very different depending on whether and when one begins to parent. Becoming a parent changes everything about how young people relate to social institutions.

Young adults have very different options and experiences depending on their family backgrounds. In addition, the greater racial and ethnic diversity of young adults today raises concerns about the limited and fragile connections that many young people have to mainstream social institutions.

In the United States, so much of the well-being of young people is linked to the resources that parents or extended family members provide. Recent data show that parents are now spending about 10 percent of their annual household incomes to support their young adult children through their early 20s (Settersten et al., 2010b). The support of parents to young adult children is also not a new phenomenon. What is new is that low-income parents are also trying to do it. At the same time, the idea that young adulthood is about freedom and exploration is mainly an experience of the privileged. “This is not a ‘problem’ that most young people in our society face,” Settersten said. Yet it is clear that some exploration in education, work, and relationships can result in positive outcomes rather

than being a detriment. “I am not sure that the point is that we want young people to go faster.”

The norms to which society holds young adults are often drawn from the middle of the 20th century. But in the larger historical picture, the post-World War II model for becoming an adult was an aberration. In some ways, young people today look more like their peers from a century ago than like their peers from the 1950s.

Because families are so important to how young adults fare, the resources of families need to be studied. Higher education is also an important area to study, especially the connection between higher education and workplaces, neighborhoods, and social networks. The effects of college go well beyond jobs and wages and include health, civic engagement, and parenting. Also, the crisis stories of the period are about men much more than women, Settersten observed. High school and college dropout, unemployment, being completely “disconnected” (not in school, work, or the military), and other negative outcomes all affect men more than women. Men who are not college bound no longer have visible pathways to productive roles. Issues of gender and the problems afflicting males need renewed attention.

Every period of life is being reworked today, from childhood through old age. Everyone is “struggling with the fact that we are trying to create a life for ourselves against a new set of conditions, against a new set of expectations, against a new set of potentials and dangers” in every life period, said Settersten. “Young adults aren’t any different.” The old model of education at the beginning of life, work throughout adulthood, and then retirement “is dead,” Settersten added, but this model still is entrenched in people’s thinking and in public policies. A person’s 20s are “terribly consequential” for what happens to that person later in life. By not reshaping policies to support young adults, risks for bad outcomes are heightened.

Success in young adulthood is not really about establishing independence, Settersten concluded. It is about the development of interdependence. “It is about the ties we form with other people, and the ways in which those ties fuel us and also hold us back. We don’t act in autonomous ways. We act in ways that are heavily conditioned by relationships with other people.”

During the presentations by the young adults at the end of the day, Amy Doherty commented on this interdependence as a way of helping young adults to navigate challenges. She is board president of the National Youth Leadership Network—a group of young adults from across the country working to break isolation and build community among young adults with disabilities. For example, many young adults know little about financial management, even though all have to deal with financial issues. Self-defense can be another problem area for young adults, she said, especially for those with disabilities.

Andrea Vessel also pointed to the importance of clubs like Girl Scouts and 4-H as major influences on a young person’s decisions and outlook on life. Young adults make consequential choices involving religion, culture, relationships, and risky behaviors, and a young adult’s affiliations can powerfully shape these choices. “I have talked to a lot of guys … who said that they think it is okay to have kids and not be married,” Vessel said. “Their outlook is to get a job, get a career, have money, and then it is okay to have children and not be connected to anyone…. My outlook is, ‘That is not okay.’” Having continuous access to programs and to other people who are making good choices creates positive images and helps young adults when they have to make tough choices themselves, even if they have few other resources on which they can draw.