Important Points Made by the Speakers

- Young adults in the military face some unique challenges as well as challenges common to all young adults. (Adelman)

- The military health care system is moving from a focus on acute care toward patient-centered care oriented around medical homes. (Hutchinson)

- The “long war” that began following the terrorist attacks of 2001 has left many soldiers with injuries and stress-related disorders. (Ritchie)

- Mitigating strategies for stress-related disorders and suicide can reduce the incidence of these outcomes. (Ritchie)

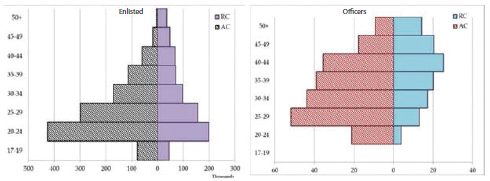

The military is an organization composed largely of young adults. As William Adelman, adolescent medicine consultant to the Army Surgeon General, pointed out, young adults ages 20-24 make up the largest cohort of both active duty and reserve military personnel (see Figure 10-1). Among active duty officers, 25- to 29-year-olds represent the largest cohort. Young adults make up the smallest proportion of the civilian workforce, Adelman observed, but they make up the largest proportion of the military. Some of the issues other young adults face are not factors in the military. Young adults in the military are fully employed, are 100 percent insured, and have access to comprehensive medical benefits for themselves and their

FIGURE 10-1 Department of Defense active component and reserve component age distributions, fiscal year 2011.

SOURCE: DoD, 2011.

families (Adelman, 2013). However, they face some unique challenges, said Adelman, as well as challenges that are common to all young adults.

Two members of the military explored these challenges at the workshop, the first from a general perspective, the second from the perspective of military members who have been in war.

MILITARY SERVICE AMONG YOUNG ADULTS

Common myths about the military are that its members are often uneducated, out of shape, or in the military because of previous legal problems. All of these myths are false, said Jeffrey Hutchinson, chief of the Adolescent Medicine Service at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

Ninety percent of those who join the military have a high school diploma. Being obese is the number one reason for not being qualified to be in the military, said Hutchinson. Having a felony is a disqualifying factor in joining the military.

“Unlike other countries where military service is required, in the United States, military service is a privilege,” said Hutchinson. “It is the military’s job to try and find people who have the most likely chance of succeeding in the military.” Some health conditions, such as seizures, asthma, or cancer, are disqualifying, but applicants can apply for a waiver to enlist. A board decides whether someone’s condition is compatible with military service. A person may need to pass a test, lose weight, or go without a medication taken previously, but if successful, that person can be allowed to join.

Everyone who wants to enlist in the military takes an armed forces qualification exam, which is similar to the SAT. One out of five people with a high school diploma still do not score high enough to join the military,

which points to the need for the education system to meet the educational needs of young adults, Hutchinson observed.

The Department of Defense’s Health-Related Survey, which is conducted every 3 years, looks at high-risk behaviors such as drinking and drug use. Compared with civilians, members of the military use illicit drugs less but drink alcohol more, even though the price of alcohol has been raised in the military commissary system to discourage heavy drinking (DoD, 2011). More men in the military binge drink than women, and men in the Marines binge drink more often than men in the Air Force (DoD, 2011).

The military health care system is free and comprehensive. All of the military services require annual health assessments, though the assessments are self-reported, so that members of the military afraid of losing a job are unlikely to report disqualifying conditions, said Hutchinson. Every service also tests each member physically, either with strength or conditioning, to make sure that minimal standards are met.

The military health care system is moving from a focus on acute care toward patient-centered care oriented around medical homes, Hutchinson said. In addition, annual training, including suicide awareness, is incorporated into military service. The military also is beginning to take advantage of new technologies to gather and disseminate health information.

Hutchinson explained that only about 17 percent of people who join the military stay in long enough to retire. The GI Bill pays for higher education leading to a 2- or 4-year degree. The Veterans Administration covers health conditions that developed or worsened during military service. Programs for veterans such as Hiring Our Heroes work in partnership with the services to help young adults assimilate into the civilian workforce. Yet veterans’ unemployment rate is about 20 percent for 18- to 24-year-olds compared with 16 percent for nonveterans. “That statistic is puzzling,” said Hutchinson. “You would imagine that someone with the discipline and work experience of being a veteran would be a great person to hire. Why are they not hired as often? That is an area ripe for research.” Hutchinson cited several other questions that research should address; these can be found in the compilation of suggestions for future research in Chapter 14.

PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF THE LONG WAR

Every war produces psychological reactions, whether called shell shock, battle fatigue, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the past, the military has tried to screen recruits to reduce problems, but “it doesn’t work that way,” said Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, chief clinical officer in the District of Columbia Department of Mental Health. “We don’t yet know who is going to develop PTSD.” Similarly, the military does not accept recruits who have had suicide attempts, but suicide also is hard to predict.

The terrorist attacks of 2001 marked the beginning of what Ritchie called the long war. Deployments in the Middle East and elsewhere have been marked by numerous stressors, including multiple and extended deployments, improvised explosive devices, sleep deprivation, and experiences with severely wounded soldiers and civilians. But soldiers in those wars have received strong support from the American people, and the military has developed a behavioral health focus and numerous new programs designed to support service members.

Several features have characterized the military during the long war, said Ritchie. It is a volunteer army, and soldiers know they are going to war. The suicide rate among soldiers and among veterans has been elevated (Ritchie, 2013). Tens of thousands of soldiers have traumatic brain injury (TBI), amputations, or other injuries. People with amputations tend to get publicity, said Ritchie, but “what you don’t hear about so much are people with their faces blown off from bombs…. That is much harder to deal with.”

Families have been affected by continuous deployments and by the injuries and deaths of family members. “We have many teenage brothers and sisters who have lost their 21-year-old brother and they are 14,” said Ritchie. “How do they make sense of that?” Wounded veterans can become completely dependent on their parents again, even if they joined the military to get away from their parents. In addition, many veterans face challenges with employment in an uncertain economy.

Deployment-related stress reactions can range from mild to moderate to severe. Symptoms of combat stress, operational stress, posttraumatic stress, and PTSD can include irritability, bad dreams, and sleeplessness, Ritchie said. Family, relationship, or behavioral difficulties can arise, along with alcohol abuse. Medical care providers, chaplains, or mortuary workers can experience compassion fatigue or provider fatigue. Veterans also can exhibit increased risk behaviors, leading, for example, to greater rates of motor vehicle accidents. Depression, alcohol dependency, and suicide all can follow combat experiences.

Ritchie described several mitigating strategies for PTSD. Evidence-based treatments include psychotherapy and medications. An evidence-informed strategy she mentioned involves virtual reality therapy, where soldiers who may be unwilling to undergo psychotherapy will interact with a therapist through a virtual world. Many soldiers respond well to service dogs (Ritchie, 2013).

Mitigating factors for suicide include unit cohesion, reintegration, reduction of pain and disability, structure, easy access to care, and stigma reduction (Ritchie, 2013). Ritchie particularly emphasized means reduction. “We really need to talk about the use of firearms,” she said. “If you go down to Fort Stewart, there are billboards everywhere saying don’t drink

and drive. You don’t have any billboards that say don’t drink and play Russian roulette.”

The military often uses group therapy, Ritchie said, especially because soldiers are always eager and willing to help their buddies. Officers are often separated from the troops that they lead in such therapy. Older and younger veterans can have difficulty relating to each other, but older veterans also can help younger veterans avoid difficulties, said Ritchie.

Congress has funded research on PSTD and TBI, usually through academic consortiums. Remaining gaps include studies of treatments, collection of longitudinal data, and studies of female service members. “Women have been in combat for a long time,” said Ritchie, noting that she wears three different combat badges from Somalia and Iraq.

This page intentionally left blank.