Key Messagesa

• Divestment from TB control has been associated with outbreaks caused by DR TB.

• Community-based care has proven to be an effective way of combating TB, including that caused by drug-resistant strains, and can improve infection control.

• Novel diagnostics and therapeutics can be introduced equitably through “care delivery platforms” linking hospitals and clinics to patients in their homes.

• Sustained and substantial investments, and also new tools, are key in the strategy for catching up with microbial drug resistance and strengthening TB control.

• Many of these lessons are applicable to other chronic diseases, including those of noninfectious etiology.

__________________

a Identified by Paul E. Farmer, Co-Founder, Partners In Health; Chair, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School; and Chief, Division of Global Health Equity, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

__________________

1 This chapter is based on the presentation by Paul E. Farmer, Co-Founder, Partners In Health; Chair, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School; and Chief, Division of Global Health Equity, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

As soon as antibiotic treatment for TB was introduced, resistance evolved; as each new antibiotic was introduced, resistance to that drug also emerged, observed Paul E. Farmer, Partners In Health, Harvard Medical School, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The story is not much different for most pathogenic bacteria, parasites, and viruses: The “crisis of antibiotic resistance” is not new, and preventing or slowing its emergence calls for better infection control and for new delivery platforms that permit treatment of patients with multidrug regimens in a manner that is convenient to them. Given the long duration of therapy, the best approaches are usually community based, Farmer argued. All this is called for as the tubercle bacillus, like other pathogens, continues to adapt. The challenge to medicine, said Farmer, is to catch up with the microbe. “Are we going to win this struggle, or is the mycobacterium?”

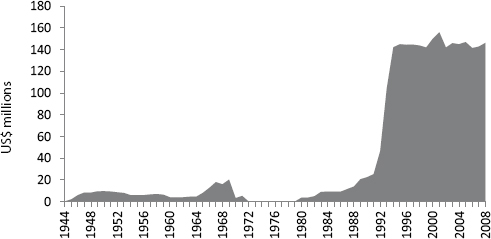

In the past, increasing wealth has had the effect of helping to reduce the burden of TB. For example, TB rates fell dramatically, albeit unevenly, in the United States and in other countries even before therapeutics became widely available. But the disease remained a ranking killer of young adults, especially those living in poverty, well into the 20th century. The decline in TB rates, hastened further by the introduction of effective therapies, led to a divestment from the TB control system. From 1944 through 1976, the U.S. Public Health Service continued to invest in TB control, but “block grants” to fund many TB services ceased in the 1970s (Figure 3-1). At that point, it was difficult to obtain funding for clinics or staff; research focused on the disease, including basic science and clinical trials, also faltered.

In the late 1980s, the incidence of TB in the United States began to rise in several major cities. The AIDS epidemic was believed to have a central role in this rise, although public health experts still debate exactly what caused the resurgence. Other contributing factors included a rise in homelessness, persistent urban poverty, immigration from TB-endemic regions, a weakened public health infrastructure, and limited access to medical care for the poor and marginalized—conditions that exist in many other cities around the world. A series of policies termed “the war on drugs” also led to a sharp rise in the prison population. The incidence of TB increased 132 percent in New York City from 1980 to 1990, with 14 percent of all U.S. TB cases occurring in New York by 1990.

The social determinants of TB epidemics also contribute to conditions that interrupt care; weaken the laboratory infrastructure needed for prompt diagnosis and for surveillance; lessen patients’ ability to complete therapy once correctly diagnosed; and worsen infection control practices in clinics, hospitals, homeless shelters, and prisons. This, of course, is a recipe for

FIGURE 3-1 Funding for TB through block grants from the U.S. Public Health Service dropped to zero in 1972 but rose substantially after the epidemic of DR TB in New York City in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

SOURCE: Farmer, 2013. Presentation at the IOM workshop on the Global Crisis of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis and the Leadership of the BRICS Countries: Challenges and Opportunities.

DR TB: By 1990, almost one in five patients with TB in New York City had MDR TB, accounting for 61 percent of the MDR TB cases in the United States.

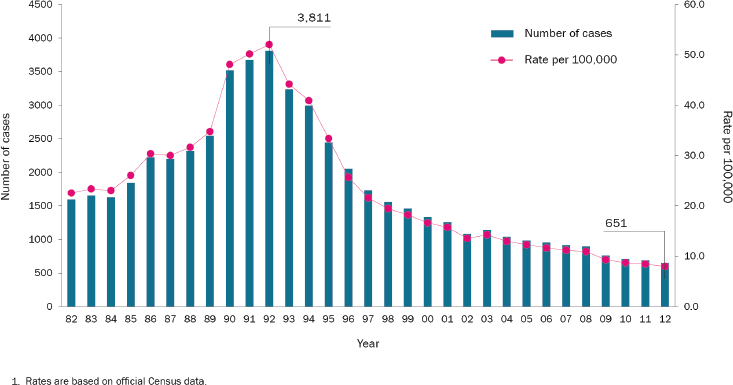

After peaking in 1992, the number of TB cases, both drug-susceptible and DR, dropped rapidly in New York City and today is lower than it was before the increase (Figure 3-2). Several critical interventions helped turn the tide, including diagnosis using mycobacterial culture; access to quality-assured SLDs; proper infection control; and delivery of care under direct observation, with management of adverse events (Frieden et al., 1995). Also critical to the response was building a system for the delivery of these interventions. Many of these patients faced other problems, including poverty and homelessness, and the public health system, like some other social services in New York, had been weakened by reduced funding. At its best, the delivery system that helped to rein in the epidemic, which took many lives and cost by some accounts up to a billion dollars, offered prompt and accurate diagnosis, effective care with a multidrug regimen proven to be active against the infecting strain, and social services that helped vulnerable patients with a variety of problems ranging from housing to transportation to and from clinic. Much of the follow-up care was delivered by outreach workers who went to the patients. Indeed, community-based care played

FIGURE 3-2 TB rates in New York City rose to a peak in 1992 and then fell rapidly as new interventions were implemented.

SOURCE: Data from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Reprinted with permission.

a role, Farmer noted, in turning the tide in New York, and has since continued to contribute to TB control. Farmer suggested that community-based care should play a greater role in settings in which long-term hospitalization is ill advised because of a lack of infection control or the inconvenience for patients of being hospitalized far from home.

In the United States, especially in areas with high incidences of HIV and poverty, community-based health care providers have been deployed to help manage TB for three decades. Community-based care of TB, which Farmer referred to as an enabling platform, is “one of the best ways to promote infection control and to prevent transmission within institutions even as it boosts cure rates.” This delivery system, while not a new drug or new diagnostic, is an important innovation nonetheless: It can be effective not just for TB, he argued, but also for other chronic infectious diseases, including AIDS and hepatitis C, and for diabetes, epilepsy, and other chronic afflictions requiring daily therapy.

Community-based care relying on community health workers has not evolved much in the United States, but recent developments designed to improve health outcomes, increase coverage, and decrease costs should make such models much more common in the treatment of chronic disease, regardless of etiology. Nor has community-based care taken hold in the BRICS countries, with a few notable exceptions entailing DR TB programs. In China, once famous for its “barefoot doctors,” community-based care is no longer as prevalent as clinic-based or hospital care, Farmer noted. Existing community-based systems have been weakened in rural areas and new ones have not yet been built as the economy has boomed, and China has become increasingly urban. Hospitals and specialty clinics are of course necessary, “but community-based care is crucial to good outcomes for chronic diseases [that are] prevalent,” said Farmer. Addressing the problem of community-based infrastructure will be central to dealing effectively and humanely with DR TB in China. Increasing wealth will help with TB control in China, as it has elsewhere, but “economic growth alone will not solve all problems,” Farmer said, “nor will it suffice to address drug-resistant TB here or in India, South Africa, or Russia.”

Early diagnosis, proper treatment, and better infection control can be applied anywhere in the world. Farmer gave two examples from his experience. Like other cities in South America and much of the rest of the world, Lima, Peru, has peri-urban slums. Patients with DR TB in the poorest reaches of Lima were said to be “untreatable,” but carefully designed multidrug regimens proved effective in more than 80 percent of MDR TB patients who had failed numerous retreatment regimens. This program

was later brought to scale through the national TB program, a stunning achievement. Even among Peruvian patients retrospectively identified as having XDR TB, again often termed “untreatable,” roughly 60 percent were cured through a comprehensive treatment program that included aggressive management of adverse events, nutritional and social support (including regular group therapy sessions), opportunities for participation in microfinance initiatives and job training, follow-up screening for recurrent disease, and efforts to reduce household and institutional transmission (Mitnick et al., 2003).

Community-based care was central to this success. The treatment regimen was grueling, including intramuscular injections, often for a year. But the patients almost never refused treatment once it was made clear that the regimens were designed based on DST; with proper social support from their community health worker (and from nurses and other providers), they rarely dropped out of care. Whether delivery platforms are convenient or inconvenient will affect compliance. But the idea that patients often refuse effective treatment, even if difficult, is “a fiction,” said Farmer. “The great majority of patients want to be treated, but they do not want another ineffective and prolonged regimen, which is what most of them received prior to initiating care for laboratory-proven MDR TB.” The intensive treatment regimen for MDR TB was scaled up to thousands of patients in Peru, which was then reporting the largest number of new TB cases in Latin America, most of them caused by drug-susceptible strains. The Peruvian experience suggests that, with the needed resources and right partnerships, national TB programs can successfully integrate care for those types of TB that are more difficult to diagnose and cure, suggested Farmer.

Another example Farmer cited was that of Rwanda, which in 1994, after the genocide, was by many criteria the poorest country in the world. Almost 20 years later, it is the only country in sub-Saharan Africa on track to meet all the health-related millennium development goals. Declines in child mortality in Rwanda during the past decade have been the steepest in the world, and mortality due to AIDS, TB, and malaria has also plummeted, as have deaths in childbirth. Many of the people who have been lifted out of poverty in recent years are in the BRICS countries, but Rwanda is also an impressive model of progress (Farmer et al., 2013).

The community health model has made a major difference in the AIDS program in Rwanda. Rwanda, along with much-richer Botswana, has the largest and most widespread access to HIV care in Africa; both are set to reach universal access to care. The quality of this care is greatly increased by including community health workers in the routine care of patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Of more than 1,000 patients in a community-based AIDS treatment program in rural Rwanda, more than 90 percent were retained in care after 2 years (Rich et al., 2012). The outcomes of MDR

TB treatment in the first cohort of Rwandan patients were as good as those registered in Peru, even though there was much more HIV coinfection in Rwanda. Enabling platforms reliably link community-based care to health centers, to hospitals, and even to prisons, Farmer said. “That is one reason why, in countries as diverse as Peru and Russia and Rwanda and Lesotho and the United States, the outcomes of community-based therapy of drug-resistant TB, even among patients held to be ‘untreatable,’ are consistently good and quite similar. They will be further improved with prompt diagnosis and with better regimens and improved infection control, as long as these innovations are included in this enabling platform.”

Resources are a critical element of success. Much more funding has gone to stemming the AIDS epidemic in recent years than to fighting TB. Money is not everything, Farmer admitted, and TB is a leading comorbidity of AIDS, but resources clearly make a difference, especially when they help resolve false debates commonly seen regarding epidemics that afflict primarily poor people. He noted by way of example that prior to the advent of resources it was common to argue that, for those living in poverty and with AIDS, prevention and care were necessarily pitted against each other. He also cited arguments about the need to determine which interventions were cost-effective and which were not. These same debates have recurred not only for DR TB but also for other pathologies, including most cancers, held to be “untreatable” in settings of poverty long bereft of robust health infrastructure and skilled personnel and the resources to build and train and support them. False “competitions” have hobbled TB control for many decades, Farmer said—prevention versus treatment, research versus delivery, domestic versus international, HIV positive versus HIV negative, drug-susceptible versus drug-resistant. “This either-or approach has been a very limiting way of thinking about a complex illness that is chronic and requires massive investment.”

Poverty reduction has helped reduce premature mortality in parts of Africa, and it is having an even more striking effect in China. According to the World Bank, China’s poverty rate has fallen from 85 percent to 16 percent in recent decades. China thus accounts for much of the world’s reduction in poverty. But economic growth does not solve every health care problem, Farmer repeated in closing. Great social and economic disparities and rapid social and economic change can contribute to an increase in DR TB (and other pathogens) even as overall disease burden falls. This is occurring in many countries now. A focus on equitable access to humane and effective care is an important step in reversing growing health disparities. Moving resources internally within a country—from where they are

typically concentrated to where they are most needed—poses significant challenges. Multidrug regimens administered for an appropriate duration will be essential until new methods of preventing and curing TB are developed. The acquisition of drug resistance in the microbes needs to be slowed through prudent but equitable access to new tools, from rapid diagnostics to novel agents effective against M.tb., and through new approaches that move safe and effective care to the communities in which patients and their families live and work. At the moment, many TB programs are not sufficiently resourced to catch up with the microbe.

Partnerships will be essential to deal with these and other complex health problems. Cooperation should be south–south as well as south–north, Farmer said, but also with those most affected by the disease, the patients and their families. Collaborations among universities, the public sector, and community health workers have proven their effectiveness in diverse settings when a patient-focused approach is embraced. When the best diagnostics and therapeutics are available as part of an equitable and humane delivery platform, many lives can be saved and many new infections averted.

The BRICS countries have, or are mustering, the technological and financial resources to enable innovation. Building an equitable and humane delivery platform will require further resources. “A lot of the answers for this global challenge are likely to come from China and from some of other countries we are calling the BRICS countries,” Farmer predicted. “I am confident that these problems, including drug-resistant TB and rising health disparities, must and will be addressed here, and that the rest of the world will learn.”

TB can be addressed effectively, Farmer concluded, only by “significant and sustained investments in protecting public health, not just in one corner of the global economy, but everywhere.”