Lessons Learned from Federal Programs

Important Points Made by Individual Speakers

- The development and implementation of national nutrition education curriculum standards need to draw on the resources, materials, and experiences of past nutrition education efforts.

- Standards need to reflect appropriate learning methods, be behaviorally focused and evidence based, have program and fiscal accountability, and be consistent with legislation and with the mission, goals, and focus of the relevant government agencies.

- Standards also need to be appropriate for the backgrounds of the multiple audiences that receive nutrition education.

- Most schools devote less time to nutrition education than the suggested amount needed to change behaviors.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has extensive experiences delivering nutrition education to school children, food assistance recipients, and other groups. The Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) and the education component of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP-Ed) have been working for decades to improve the food literacy and eating patterns of low-income groups. The Nutrition Promotion and Technical Assistance Branch in the Child Nutrition Division of USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) supports a wide variety of efforts to enable children and adolescents to make healthy eating choices.

And USDA supports and conducts research on the nature and extent of nutrition education in the United States. Three USDA speakers at the workshop described these programs and summarized this research.

LOW-INCOME NUTRITION EDUCATION THROUGH THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE: EFNEP AND SNAP-ED

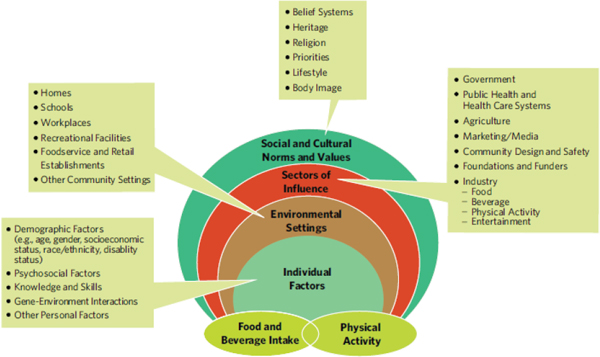

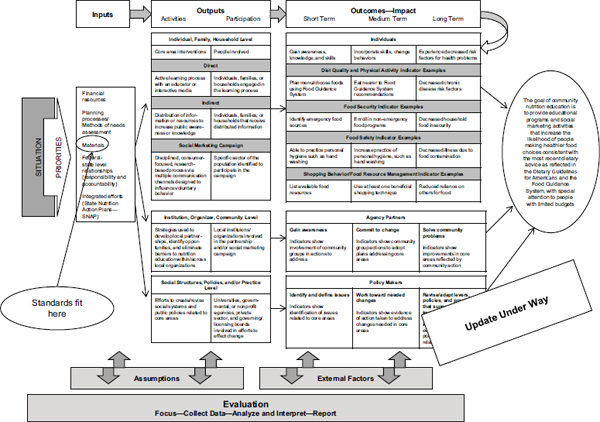

Both EFNEP and SNAP-Ed employ a social ecological framework for nutrition and physical activity decisions (see Figure 4-1) and a community nutrition education model for programmatic decisions (see Figure 4-2), said Helen Chipman, national program leader in the Nutrition Division of USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA). Standards for nutrition education play a role in each of these models, as they do in the programs these models inform.

The purpose of EFNEP is to bring together federal, state, and local resources to improve the health and well-being of limited-resource families and youth. Created in 1969 and administered by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, it currently is provided by 75 land-grant universities in all 50 states, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia (USDA-NIFA, 2013) and had a federal allocation in fiscal year (FY) 2012 of $67.9 million (P.L. 112-55, Div. A). It uses a paraprofessional model to provide education by peers, which can foster behavioral change at the local level and within communities. It also uses a series of hands-on, interactive lessons and a learner-centered approach that extends across the lifespan and has a strong structure for supervision and for the delivery of content knowledge.

EFNEP addresses four core areas:

- Health issues, including diet quality and physical activity education;

- Food access and security issues;

- Economic issues, including food resource management education; and

- Food safety issues.

The program has a strong data collection component. Data collection provides focus, facilitates program accountability, informs program leadership decisions, guides program management decisions, and is useful for all users at the local, state, and national levels, said Chipman. These data reveal that the program is available in approximately 800 counties and directly reaches more than 130,000 adults and 450,000 youth, and indirectly reaches nearly 400,000 family members. Approximately 85 percent of EFNEP families are at or below the poverty line, earning $22,350 a year or less for a family of four, and 73 percent of EFNEP adults are minorities (USDA-NIFA, 2013). Among youth and children, more than two-thirds are

FIGURE 4-1 A social ecological framework for nutrition and physical activity decisions incorporates different levels of influence. SOURCE: USDA and HHS, 2010.

FIGURE 4-2 A community nutrition education logic model indicating that nutrition standards would be incorporated in the education materials made available as inputs. SOURCE: Chipman, 2013.

reached through in-school programming, receiving on average six sessions and 8.8 contact hours (S. Blake, USDA-NIFA, unpublished data, 2013). Although states have flexibility in how to allocate their EFNEP funding to meet the needs of their populations, Chipman emphasized the importance of schools in nutrition education.

Because the emphasis is on hands-on activities, students read labels, try a variety of foods, improve food preparation and safety practices, and increase their ability to select low-cost nutritious foods. As an example of these activities, Chipman quoted a peer educator in the Alaska EFNEP program:

When I arrived to teach nutrition, the kids were always eating candy and drinking soda from the snack bar. I talked with the staff and the director about it and eventually a few nutritious items were added, but the candy always sold first. After going over label reading, we took the youth shopping. They were amazed at the high sodium, sugar, and fat of snack bar items. They, by themselves, eliminated items from the list because they weren’t nutritious. They voted to make the snack bar a candy-/soda-free zone, and the director supported it. These young people are making healthy choices and developing healthy habits.

Turning to SNAP-Ed, Chipman said that the goal of the program is to improve the likelihood that persons eligible for SNAP will make healthy food choices within a limited budget and choose physically active lifestyles consistent with the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans and USDA’s Food Guidance System. Begun in 1992, the program currently serves all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands. It is administered by the Food and Nutrition Service and had an allocation of $388 million in FY 2012 (USDA-FNS, 2013b). State SNAP agencies apply for the funds, while subcontractors such as universities, public health agencies, food banks, and nonprofit organizations implement the program.1

Within the context of the program’s defined audiences and policies, SNAP-Ed uses individual or group-based nutrition education, health promotion, and intervention strategies that are comprehensive and multilevel. Community and public health approaches also help improve nutrition.

The desired outcomes tend to be more granular and concrete than for EFNEP. They include the following:

- Make half your plate fruits and vegetables, at least half your grains whole grains, and switch to fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products.

__________

1 See http://www.fns.usda.gov/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-education-snap-ed.

- Increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviors as part of a healthy lifestyle.

- Maintain appropriate calorie balance during each stage of life: childhood, adolescence, and adulthood; pregnancy and breastfeeding; and older age.

According to 2012 data, more than 6 million participants were taught directly and an additional 76 million contacts were made directly through SNAP-Ed (U. Kalro, USDA FNS, personal communication, 2013). These are two mutually exclusive ways the data are collected, as participants and as contacts. Of those who were taught directly, more than two-thirds of the participants were in the K-12 grade range. Direct education was provided in more than 53,000 learning sites, including schools, before-school and after-school programs, community centers, work sites, and other places where youth and adults congregate. SNAP-Ed also engages in social marketing campaigns and indirect education, which involves mass communication, public events, and material distribution. Many more people are reached through these additional approaches.

According to a review of SNAP-Ed delivered through land-grant universities, more than half of participants for whom evaluation data were collected indicated eating closer to the recommended amounts of grains, vegetables, and fruits; and 38 to 62 percent of participants, depending on the specific program, increased physical activity (Sexton, 2013). More than three-quarters reported improved hygiene, such as hand washing, and about half adopted the use of safe temperatures to store food. About one-third adopted beneficial shopping, preparation, and storage practices, and 78 percent tried new foods or recipes.

Chipman concluded by talking briefly about standards and other essential elements of nutrition education. Standards have a variety of benefits, including increased consistency in teaching. However, their use can create challenges where states or districts have different and sometimes contrasting requirements for standards. Linking nutrition standards with other education standards, such as mathematics and science standards, is critical, said Chipman. “That is a way to get a foot in the door. It’s also a way of making things easier for teachers.” Moreover, nutrition standards can complement what is happening in homes and communities. “It’s a synergistic effect that can happen as we put these pieces together.”

Educational programs also need to reflect appropriate learning methods, be behaviorally focused and evidence based, have program and fiscal accountability, and be consistent with legislation and with the mission, goals, and focus of the relevant government agencies. Nutrition education needs to be age appropriate, culturally appropriate, and audience appropriate, which can be a challenge with multiple audiences. Research is essential

both to develop the evidence on which to base practice and to determine whether the evidence being gathered answers the right questions. One way the National Institute of Food and Agriculture has gathered evidence is through Agriculture and Food Research Initiative childhood obesity prevention grants, which seek to develop effective obesity prevention strategies that take into account behavioral, social, cultural, and environmental factors. These grants also are designed to develop effective behavioral, social, and environmental interventions.

As an example of a successful nutrition education intervention, Chipman cited the KidQuest program in South Dakota, which is a school-based nutrition and physical activity curriculum designed especially for fifth- and sixth-graders. It features activity supplements, leaders’ guides, healthy homework worksheets, and 10-minute activities. Each nutrition lesson includes a brief instructional slideshow followed by hands-on group activities. The nutrition lessons are approximately a half-hour long, with physical activity lessons provided if more time is available. The lessons are linked to food dietary guidelines and current food messages. The nutrition lessons build on concepts related to nutritional information and behaviors in a sequential manner, so they work best if they are provided in order. To maximize the educational benefit and encourage behavioral change, it is recommended that the lessons be provided at least 1 week apart from each other.

Since its inception in 2004, KidQuest has been pilot tested and evaluated for efficacy in more than 40 South Dakota schools. Improvement has been seen in the behaviors of overall fruit and vegetable intake and decreased consumption of sweetened beverages, and in the skill of reading food labels (Jensen et al., 2009). Beginning in 2009, additional research components have included objective anthropometric and biochemical measures. Ten graduate students already have used or are planning to use data from the program for their master’s or doctoral work. “We are starting to connect all the dots in terms of what we’re trying to accomplish,” said Chipman.

TEAM NUTRITION AND THE HEALTHIERUS SCHOOL CHALLENGE

The Nutrition Promotion and Technical Assistance Branch in the Child Nutrition Division of USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service—which goes by the name Team Nutrition—is divided into the two categories embodied in its name,2 said the branch chief, Eileen Ferruggiaro. The technical assistance component generally is directed at the people who run school food and nutrition programs, including kitchen personnel and school nutrition di-

________________

rectors. For example, Team Nutrition provides the Food Buying Guide for Child Nutrition Programs that enables schools to calculate how much food to purchase to meet the portion sizes required by regulations. “Our portion sizes are much smaller than you’ll find in restaurants,” said Ferruggiaro. In addition, Team Nutrition offers one-page fact sheets for school nutrition professionals on such topics as trans fats, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and whole grains. “When they’re working with the staff in the cafeteria, they have a basic knowledge and know why they’re adjusting their recipes and menus to meet these new requirements.”

A new online recipe book, Recipes for Healthy Kids, includes student-tested and student-approved recipes that were developed for the new school meal pattern. The recipes include whole grains, healthy vegetables, and no more than 15 ingredients commonly available to school food services and are low in total fat, saturated fat, sugar, and sodium. The recipes are at three different levels: 50 and 100 servings for schools, 50 and 25 servings for child care settings, and 6 servings suited for homes. If a school provides a healthy meal in the cafeteria, the same recipe can be made at home.

Promotional materials such as posters reinforce the provision of healthier options. For example, a promotional package, Healthier Middle Schools: Everyone Can Help, has resources aimed at principals, teachers, students, parents, and community members. Short video clips introduce the changes in meals while handouts can go home with students.

An example of the nutrition education materials provided by Team Nutrition is Nutrition Voyage: The Quest to Be Our Best, which is a series of lessons for grades seven and eight that takes students on an exploratory journey into school wellness. The lessons, which are presented in the form of treks, have been tested on focus groups and are integrated with mathematics, science, and the language arts.

Another example, for grades one through six, is Serving Up MyPlate. The lessons include original songs that students can sing and dance about fruits, vegetables, and whole grains as well as teacher guides. Parent handouts in English and Spanish can go home, with handouts in French and Chinese on the way.

Materials being developed at the time of the workshop included a nutrition education curriculum for kindergartners, an update of the Two Bite Club, which is a storybook aimed at preschoolers and kindergartners, an update of Grow It, Try It, Like It!, which is a gardening curriculum for the same age group, and a nutrition education and gardening curricula for third through sixth graders. “If the kids know where their food comes from, they’re more likely to eat it,” said Ferruggiaro. Table 4-1 lists all of the above mentioned resources with the link to their website.

She also described the HealthierUS School Challenge, which is a voluntary certification initiative recognizing excellence in school nutrition

TABLE 4-1 USDA Team Nutrition Resources

|

|

||

| Resource | Website | |

|

|

||

| Food Buying Guide for Child Nutrition Programs | http://teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/foodbuyingguide.html | |

| Recipes for Healthy Kids | http://teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/recipes_for_healthy_kids.html | |

| Healthier Middle Schools: Everyone Can Help | http://teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/healthiermiddleschools.htm | |

| Nutrition Voyage: The Quest to Be Our Best | http://www.fns.usda.gov/tn/Resources/nutritionvoyage.htm | |

| Serving Up MyPlate: A Yummy Curriculum | http://www.fns.usda.gov/tn/resources/servingupmyplate.htm | |

| Two Bite Club* | http://teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/2biteclub.html | |

| Grow It, Try It, Like It!* | http://teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/growit.html | |

|

|

||

| * Currently being updated. | ||

and physical activity. The challenge has been aimed primarily at preparing schools for changes based on the 2010 dietary guidelines. Schools that received a HealthierUS School Challenge award have had much less difficulty adjusting to the new meal patterns, Ferruggiaro said. Schools start at the bronze level and work their way through three subsequent levels. Criteria include participating in the school lunch and school breakfast programs, offering reimbursable breakfasts and lunches that reflect the dietary guidelines and meet USDA nutrition standards, providing more nutritious competitive foods, having a local wellness policy, and providing nutrition education, physical education, and opportunities for other physical activity outside of physical education. Meal requirements include providing foods that are rich in whole grains, dark green and red/orange vegetables, legumes, and fruits. The requirements also call for variety and for at least some fresh fruits and vegetables, along with additional amounts of whole grain–rich and vegetable subgroups.

The criteria are focused on the entire school environment as well as on homes and the community. For example, the criteria for nutrition education excellence could include the use of Team Nutrition education curricula or work with a chef in the Chefs Move to Schools program, the criteria for physical activity excellence could include promotion of walking to school and recess before lunch, while the criteria for school farm service excellence

could include farm-to-school initiatives or Smarter Lunchroom techniques. The criteria also cover fundraising and wellness policy initiatives.

Schools receive incentive awards ranging from $500 to $2,000—“it isn’t very much money for the amount of work they go through, but it does help, and they get recognition.” They also get a banner and plaques that many schools proudly display. “It helps so much for the school and nutrition people to realize that we are the people helping with the health of your kids.” More than 5,000 schools had qualified for the HealthierUS School Challenge at the time of the workshop, and the number had been growing rapidly.

A STATISTICAL OVERVIEW OF NUTRITION EDUCATION

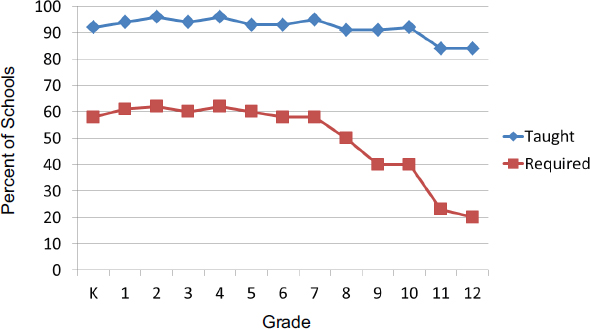

Jay Hirschman, director of the special nutrition staff in the Office of Research and Analysis at USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service, provided a statistical overview of research that has been done on the nature and extent of nutrition education. Data collected in 1995 from 916 public schools showed that most schools taught nutrition, with a slight decline in the last 2 years of high school (see Figure 4-3). According to a report published a few years later, 88 percent of K-5 teachers taught about nutrition in school year 1996-1997, and the mean number of hours during which nutrition was

FIGURE 4-3 Percent of public schools where nutrition was taught and where nutrition education was required by school district or states in 1995. SOURCE: Celebuski and Farris, 1996.

taught was 13 per year (Celebuski and Farris, 2000). As Hirschman pointed out, this is significantly less than the 50 hours mentioned by Contento.

The Team Nutrition initiative has undergone extensive evaluation, Hirschman observed, starting with a pilot of the program in the 1990s. Team Nutrition was designed to deliver nutrition education through multiple and reinforcing channels:

- Student exposure to at least one Team Nutrition public service message,

- Student receipt of Team Nutrition classroom instruction,

- Student participation in Team Nutrition cafeteria events,

- Student participation in Team Nutrition community activities,

- Parent participation in Team Nutrition or any other nutrition events at school, and

- Parent participation in Team Nutrition or any other nutrition activities at home.

An evaluation of the pilot found that students who reported an increase in the number of channels through which they received information also reported a progressive increase in improved nutrition behaviors, which testifies to the “sound underpinning” of the Team Nutrition effort, according to Hirschman.

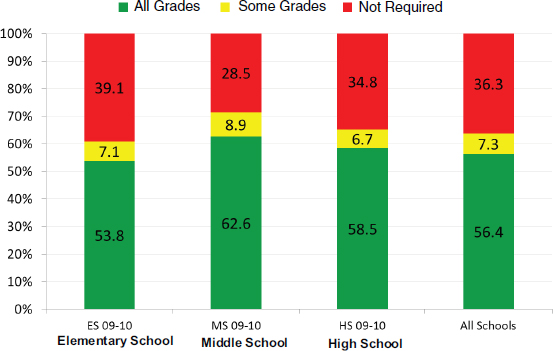

Also since the 1990s, four School Nutrition Dietary Assessment (SNDA) studies have been conducted. A list of topics covered in past SNDA studies is shown in Box 4-1. In the most recent study, which reported on data collected from a national sample of public schools in school year 2009-2010, slightly fewer than two-thirds of all schools had a requirement for classroom-based nutrition education in all or some grades (see Figure 4-4). However, 36 percent of all schools did not require such education. “We haven’t quite got everybody convinced yet that this is the right thing to do,” Hirschman said.

Among the schools requiring nutrition education in class, the majority required fewer than 5 hours or between 5 and 10 hours of instruction (see Table 4-2), but some schools fell into the range of 21 to 100 hours of nutrition education per year.

A separate survey supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found significantly smaller numbers for hours of instruction that teachers provide on nutrition and dietary behavior, ranging from a median of 3.4 in elementary school classes to 5.9 in high schools (Kann et al., 2007). However, this survey also asks about instruction on a wide range of other health topics, which may affect the results, Hirschman said.

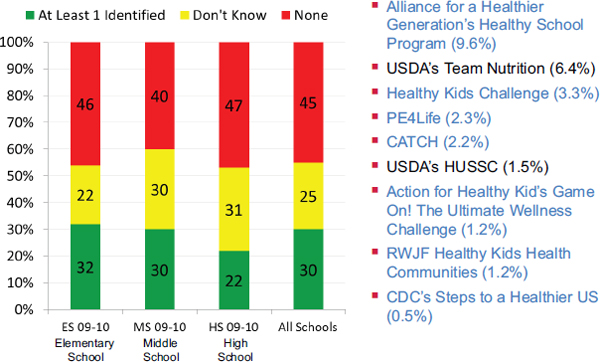

The most recent SNDA study also surveyed principals about their schools’ participation in specific nutrition wellness initiatives (see Fig-

BOX 4-1

Topics Covered in the School Nutrition

Dietary Assessment Studies

- Student participation

- Meal prices

- Menu planning and meal production

- Meal service practices

- Food safety and sanitation

- Staff education, experience, and credentials

- School wellness policies and practices (including classroom-based nutrition education)

- Meal scheduling

- Competitive foods

- Foods offered in the school lunch and school breakfast programs and after-school snacks

- Calorie and nutrient content of school meals and afterschool snacks

- Availability of meals that meet standards

- Potential contribution of meals to USDA Food Patterns

- Changes in school meals since implementation of the School Meals Initiative

- Schools participating in the HealthierUS School Challenge

SOURCE: Fox et al., 2012.

ure 4-5). Of the 30 percent of principals who were able to identify at least one such initiative, Team Nutrition was mentioned by 6.4 percent and the HealthierUS School Challenge was mentioned by 1.5 percent.

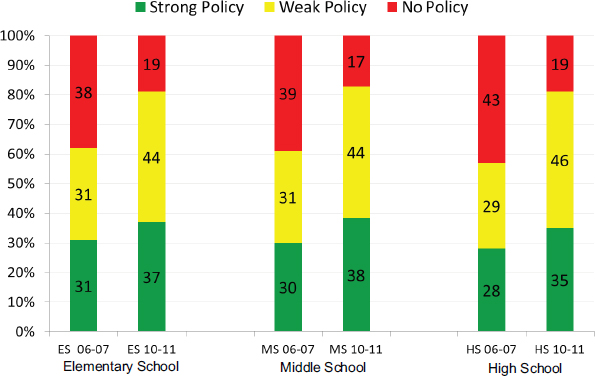

Another initiative mentioned by Hirschman, the Bridging the Gap program supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), has monitored school policies following the federal mandate requiring the establishment of local wellness policies in schools. This longitudinal study has found a strengthening of school policies over time at each grade level (see Figure 4-6). It also has found a greater emphasis over that period on behaviorally focused skills at all grade levels (Chriqui et al., 2013).

The most recent SNDA study also collected data about changes in schools participating in the HealthierUS School Challenge. Though the sample size for the available data was small and nonrandom, participating schools did a better job than elementary schools nationwide in offering and serving lunches that met standards of the School Meals Initiative for calories and nutrients. These schools also were more likely to have requirements for classroom-based nutrition education, and food service staff at these

FIGURE 4-4 Almost two-thirds of public schools surveyed in school year 2009-2010 required classroom-based nutrition education.

SOURCE: Hirschman, 2013. Data from Fox et al., 2012.

TABLE 4-2 Number of Hours of Required Classroom-Based Nutrition Education per Year, 2010

|

|

||||

| Percent of Schools in Grade Level | ||||

|

|

||||

| Elementary | Middle | High | All Schools | |

|

|

||||

| <5 Hours | 21 | 15 | 11 | 18 |

| 5 to 10 | 41 | 25 | 21 | 33 |

| 11 to 20 | 17 | 11 | 11 | 14 |

| 21 to 100 | 14 | 23 | 19 | 16 |

| >100 | 0.6 | 11 | 15 | 6 |

| Missing | 9 | 15 | 23 | 13 |

|

|

||||

| SOURCE: Hirschman, 2013. Data from Fox et al., 2012. | ||||

FIGURE 4-5 About 30 percent of surveyed principals could identify at least one wellness initiative in which their schools participated.

SOURCE: Hirschman, 2013. Data from Fox et al., 2012.

FIGURE 4-6 More schools report stronger nutrition education curriculum policies since 2006.

SOURCE: Hirschman, 2013. Data from Chriqui et al., 2013.

schools were more likely to participate in activities promoting good nutrition, such as conducting a nutrition education activity in the food service area, participating in a school meeting about local wellness policy, attending a PTA or other parent group meeting to discuss the school food service program, or participating in a nutrition education activity in the classroom.

Finally, Hirschman noted that plans are under way for the fifth SNDA study. Data will be gathered in school year 2014-2015, and the study will look at meal costs to relate the costs of meals and meal production to the nutritional quality of the meals produced. He encouraged workshop participants who have ideas about the study design to provide input to the planning process.

This page intentionally left blank.