Assessment of Risk in Pregnancy

Risk assessment in pregnancy helps to predict which women are most likely to experience adverse health events and enables providers to administer risk-appropriate perinatal care. While risk assessment and the challenge of defining “low risk” was a topic that was revisited several times during the course of the workshop, this chapter summarizes the Panel 2 workshop presentations which focused exclusively on the topic and included suggested topics for future research. See Box 3-1 for a summary of key points made by individual speakers. The panel was moderated by Benjamin Sachs, M.D., Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana. Also summarized here is the combined Panel 1 and 2 discussion with the audience (i.e., on topics covered both here and in Chapter 2).

IDENTIFYING LOW-RISK PREGNANCIES1

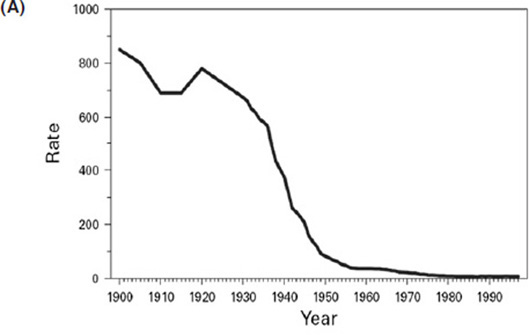

The steady declines in maternal and neonatal mortality across the United States illustrated in Figure 3-1 are among the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century (CDC, 1999). The declines were driven by many technical and political changes, starting in 1933 when the first maternal and child morbidity and mortality reviews were convened. The shift from home to hospital births that occurred during the 1940s, coupled with the use of antibiotics and transfusions in the 1950s, drove further declines, bringing maternal mortality down to about 7 per 100,000 by 1982

______________________________________

1This section summarizes information presented by Kimberly Gregory, M.D., M.P.H., Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, California.

BOX 3-1

Assessment of Risk in Pregnancy:

Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

- Kimberly Gregory noted while the steady declines in maternal and neonatal mortality across the United States are among the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century, the maternal mortality rate has been increasing in recent years.

- Gregory emphasized the dynamic nature of low risk: the risk associated with childbirth can change at any point, often unexpectedly. She also emphasized the contextual nature of risk, for example with risks of both maternal and neonatal events being low in collaborative care situations where events are triaged appropriately.

- Gregory urged a greater focus on identifying conditions that call for different levels of care. Just as high-risk women need to be cared for in appropriate facilities with appropriate resources, the same may be true of low-risk women given that care of low-risk women in high-risk or high-intervention sites is associated with increased adverse events.

- Elizabeth Armstrong observed that numerous sociological and anthropological studies have identified control and safety as being especially important for the birth experience. However, control and safety have different meanings for different women. For some women, a technology-intensive birth in a hospital imparts a desired sense of control. For others, the same situation makes them feel out of control.

- Armstrong described contemporary American culture as a “risk society,” one that views birth as a high-risk and dangerous endeavor. Some social scientists believe that the attempt to classify births into varying levels of risk itself emphasizes the pathology inherent in birth rather than the normal physiology of birth.

- As described by Kathryn Menard, the purpose of risk assessment is to predict which women are most likely to experience adverse events, to streamline resources to those who need them most, and to avoid unnecessary interventions.

- Identifying low obstetric risk is a difficult challenge. Menard elaborated on how low risk is defined differently by different researchers, making it difficult to compare outcomes across settings. She emphasized the need for more consistent and evidence-based criteria of low obstetric risk and called for a greater understanding of predictors of both neonatal and maternal complications to guide decisions about level of care and a better understanding of predictors that should prompt maternal transfer.

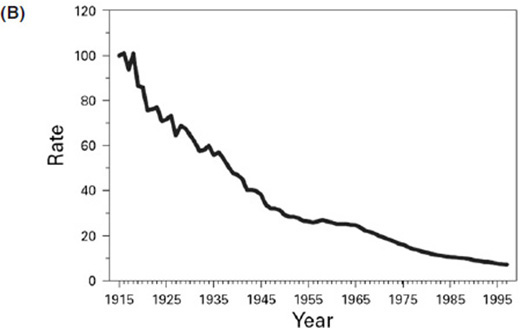

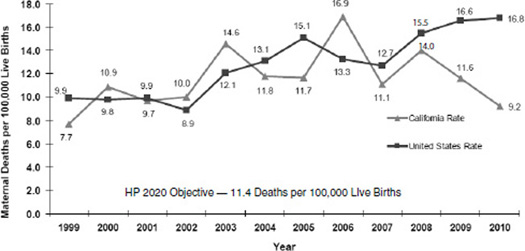

(from greater than 800 per 100,000 in 1900). However, more recently, based on data from the Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division of the California Department of Public Health, there is very clear evidence that the maternal mortality rate is increasing (see Figure 3-2). In the mid-

FIGURE 3-2 Maternal mortality rate, California and the United States, 1999-2010.

NOTES: HP2020, Healthy People 2020; ICD, International Classification of Diseases. State of California, Department of Public Health, California Birth and Death Statistical Master Files, 1999-2010. Maternal mortality for California (deaths ≤42 days postpartum) was calculated using ICD-10 cause-of-death classification (codes A34, O00-O95, O98-O99) for 1999-2010. U.S. data and Healthy People 2020 Objective were calculated using the same methods. U.S. maternal mortality data are published by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) through 2007 only. U.S. rates from 2008-2010 were calculated using NCHS Final Death Data (denominator) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wonder Online Database (http://wonder.cdc.gov) for maternal deaths (numerator). Produced by California Department of Public Health, Center for Family Health, Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division, April 2013.

SOURCE: California Department of Public Health, 2013.

2000s, the national rate was about 13 deaths per 100,000. In California, it was about 16 per 100,000.

What Is Low Risk?

Tasked to identify low-risk pregnancies, Kimberly Gregory began by searching the scientific literature, restricting her search to publications since 1996 and to developed countries. She searched using several combinations of terms: “low risk” and “pregnancy”; “risk assessment” and “pregnancy”; “levels of care” and “pregnancy”; and all of those same terms crossed with “midwives,” “family practice,” “birth centers,” and “home births.” Later, she updated her search to include maternal transfers. Gregory also considered discussions of low risk in consensus statements issued by representative

organizations and on the websites of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM), American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and American Association of Birth Centers (AABC).

Gregory observed that the history of risk assessment in obstetrics began in 1929, in the United Kingdom (UK), when Dr. Janet Campbell implied, “the first requirement of a maternity service is effective supervision of the health of the woman during pregnancy” (Dowswell et al., 2010). Thereafter, the UK Ministry of Health set antepartum exams to begin at 16 weeks, to occur again at 24 and 28 weeks, and then to occur monthly to 36 weeks and weekly thereafter. Examiners were advised to check fundal height, fetal heart, and urine. It was advised that medical officers conduct the week 32 and 36 exams. These standards form the basis for current antenatal care, although additional screening interventions for identifying “high risk” have been added over time. Mead and Kornbrot (2004) defined the “standard primip”2 eligible for midwifery care in the United Kingdom as a woman who is Caucasian, 20-34 years old, taller than 155 centimeters, with a singleton and vertex pregnancy greater than 37 weeks, with the delivery setting occurring as planned, and with no medical complications.

In the United States, identification of obstetric “low risk” is made more complicated than it is in the United Kingdom by questions such as, at low risk for what? Most risk-assessment models are for preterm birth, perinatal morbidity and mortality, Cesarean delivery, or vaginal birth after Cesarean or uterine rupture. No risk-assessment models, or tools, specifically address the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality. Because no such tools exist, and given that home and birth center births are supposed to be low risk, Gregory examined criteria used to identify candidates for home and birth center births as a means of identifying “low risk.”

According to criteria posted on the Open Door Midwifery website,3 in order to be a candidate for home birth, exam and laboratory tests must be within normal limits and show no evidence of chronic hypertension, epilepsy or seizure disorder, HIV infection, severe psychiatric disease, persistent anemia, diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, endocrine disease, multiple gestation, or substance abuse.

According to the American Public Health Association (APHA) Guidelines for Licensing and Regulating Birth Centers (APHA, 1982), birth centers themselves should specify criteria for establishing risk status in their policy and procedure manuals and clearly delineate and annually review medical and social risk factors that exclude women from the low-risk antepartum group. Referencing several older papers (Aubry and Pennington,

______________________________________

2Primip is a woman who is having her first baby.

1973; Hobel et al., 1973, 1979; Lubic, 1980; March of Dimes, Committee on Perinatal Health, 1976; Sokol et al., 1977), the APHA guidelines identify some specific high-risk conditions: recurrent miscarriage, history of still birth, history of preterm birth hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, anemia or Rh disease, renal disease, thyroid disease, toxemia, macrosomic infant, multiparity, “multiple problems,” systemic conditions like sarcoid or epilepsy, drug or alcohol use, and venereal disease. Gregory noted that the APHA guidelines emphasize continual evaluation through the prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum periods. However, again, their focus is on perinatal risk, not maternal risk.

“High-risk” conditions are usually what Gregory described as a “sign of the times.” That is, they change over time. For example, Aubry and Nesbitt (1969) included tuberculosis in their list of high-risk conditions, along with bacteriuria, uterine anomalies, and other conditions. Today, in addition to many of the same conditions listed elsewhere, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)/ACOG Guidelines for Perinatal Care, 7th edition (AAP and ACOG, 2012), include some new conditions: prior deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, chronic anticoagulation, and family history of a genetic disorder. Like the 1982 APHA guidelines, the AAP and ACOG 2012 guidelines emphasize ongoing risk assessment. They also emphasize referral and consultation among institutions that provide different levels of care.

So what is “low risk”? “It is the opposite of high risk,” Gregory said. She paraphrased Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart: “I imply no criticism of … [the literature] which in those days was faced with the task of trying to define what may be undefinable…. I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that short hand description; concluding perhaps, I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But, I know it when I see it.”

Given Low Risk, What Happens to You?

Outcomes for low-risk mothers depend on where they deliver and who takes care of them. Villar et al. (2001) evaluated patterns of prenatal care and found no difference in risk of Cesarean, anemia, urinary tract infections, or postpartum hemorrhage between midwife, general practice, and obstetric care. They reported a trend toward lower preterm birth, less antepartum hemorrhage, and lower perinatal mortality with midwife and general practice care; significant decreases in pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) and eclampsia with midwife and general practice care; a significant increase in failure to diagnose malpresentation with midwife and general practice care; and a similar or higher satisfaction with midwife and general practice care.

Other studies have shown wide variation in care for healthy women, but more consistent care with complicated deliveries (Baruffi et al., 1984). Care is dictated by the structure, process, and culture where that care is being administered. For example, Gregory said evidence suggests that, for low-risk women, midwife-led care is better (i.e., results in fewer interventions) in freestanding or integrated birth centers where midwives have autonomy and where they are practicing in a small-scale setting. Midwives in integrated centers tend to incorporate the risk culture of the environment at large, such that midwives in units with high intervention rates perceive intrapartum risk to be greater and underestimate the likelihood to progress normally (Mead and Kornbrot, 2004). Gregory explained midwives in high-intervention environments are more likely to “risk out” a patient than are midwives working in low-intervention environments.

Approximately 20 percent of laboring women are transferred out of midwifery care, based on the Walsh and Devane (2012) and Hodnett et al. (2010) reviews. Lynch et al. (2005) reported an intrapartum transfer rate from hospitals without Cesarean delivery capabilities of 9.5 to 12 percent. Stapleton et al. (2013) reported that, of 18,084 women accepted for birth center care (of 22,403 who planned a birth center birth on entry to prenatal care), 13.7 percent (2,474) were transferred antenatally to a medical doctor for medical or obstetrical complications (primarily postdates, malpresentation, PIH, and nonreassuring fetal heart rate) and 0.2 percent (36) never presented to the birth center in labor. Thus, a total of 15,574 women planned and were considered eligible for birth center care at onset of labor. Of those, 4.5 percent transferred at the onset of labor but still prior to admission; another 12 percent (of those still on track for a birth center birth) were transferred intrapartum (e.g., because of arrest, nonreassuring fetal heart rate, diagnosis of breech, bleeding, PIH, cord prolapse, or seizure). Of note, less than 1 percent of the intrapartum transfers were emergency transfers, which Gregory interpreted to mean that there was plenty of time to make arrangements for getting the women safely to a nearby hospital. Also of note, 82 percent of the intrapartum transfers were for nulliparous women. Finally, another 2 percent (of those who actually delivered in the birth center) were transferred postpartum, primarily because of postpartum hypertension or postpartum hemorrhage. But again, only less than 0.5 percent of those transfers were emergency transfers, alluding to the fact that there was plenty of time to ensure that women were receiving appropriate levels of care. The researchers concluded that fetal and neonatal mortality rates among the birth center births were consistent with those of low-risk births reported elsewhere in other settings, including hospital births.

In her search for additional information to help guide the identification of obstetric low risk, Gregory identified Baskett and O’Connell (2009) as another relevant study. The researchers examined a 24-year period (1982-

2005) of maternal transfers for critical care from freestanding birth units. They identified 117 transfers out of 122,000 deliveries (so 1 in 1,000). Eighty percent of the transfers (95/117) were for intensive care unit (ICU) care and the other 20 percent (24/117) were for medical or surgical care not available at the obstetrics unit. Most transfers (101/117) were postpartum, the remainder (16/117) antepartum. Hemorrhage and hypertension accounted for 56.4 percent of indications for transfer. Overall mortality was fairly low (only 5 deaths out of 122,000 deliveries), with a death-to-morbidity ratio of 1 to 23.

In Gregory’s opinion, available data and guidelines suggest that the 30-minute rule of “decision to incision” for emergency Cesarean delivery might not be good enough (Minkoff and Fridman, 2010). She suggested that there might be specific conditions under which care providers should be thinking in terms of “golden minutes.” These include placenta previa/accreta, abruption, cord prolapse, and uterine rupture. She acknowledged, however, that, as Lagrew et al. (2006) pointed out, “most emergent Cesarean deliveries develop during labor in low-risk women and cannot be anticipated by prelabor factors” (p. 1638).

Conclusion

In conclusion, Gregory defined low risk as singleton, term, vertex pregnancies, and the absence of any other medical or surgical conditions. Low risk is a dynamic condition, one subject to change over the course of the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum periods. The change can be acute and unexpected.

Low risk can also be defined regionally or locally within the context of collaborative care. Rates of neonatal and maternal adverse events are low if events are triaged appropriately with skilled clinicians. Recognizing that 39 percent of deliveries occur in hospitals where there are fewer than 500 deliveries per year, or fewer than approximately two deliveries per day, clearly not all hospitals can provide the same standard of care. While volume is usually associated with outcome, this is not true of midwifery care. Small-scale midwifery care is associated with better outcomes in terms of fewer interventions.

Gregory urged an evaluation of risk-appropriate care within the context of both risk (low risk versus high risk) and alternate birth settings. More data are needed regarding conditions that call for high-level care, such that high-risk women and/or conditions are cared for in appropriate facilities with appropriate resources. For example, what maternal conditions require delivery at Level III (specialty) or IV (regional site)? Low-risk women may also need to be cared for in appropriate facilities with appro-

priate resources, given that care of low-risk women in high-risk or high-intervention sites is associated with increased adverse events.

SOCIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE ON RISK ASSESSMENT IN PREGNANCY4

Looking beyond historical trends in childbirth and who chooses which settings, Elizabeth Mitchell Armstrong examined factors that drive women’s decisions about where to give birth. More specifically, what drives a woman’s understanding of risk? She looked through three different “lenses” on, or frameworks, for understanding, risk: (1) cultural views of risk and birth, that is, the sociocultural perception of birth in contemporary American society; (2) women’s perceptions, expectations, and experiences of birth and, in particular, the ways some women’s assessments of risk differ from those of their providers; and (3) structural conditions that affect risk.

Sociocultural Views of Risk and Birth in Contemporary American Society: The Notion of a “Risk Society”

Contemporary American culture views birth as a high-risk endeavor. The dominant cultural view of birth among medical professionals, as well as among laypersons, is that birth is inherently risky, even dangerous. Birth is depicted in popular movies like Knocked Up and in television shows like Birth Story as a chaotic, bloody affair involving lots of urgency, running around, and yelling. The model mood is one of panic. The birthing woman herself is depicted as irrational and out of control and the men around her as incompetent. Thus, birth is depicted in the media as a full-blown crisis, with vanishingly few planned home births depicted at all. In television and the movies, the only births occurring outside hospitals are precipitous ones; often, no one is in charge, and the birth resembles nothing so much as an unmitigated disaster. Also in the media, extreme pain is depicted as something with no other solution but drugs. Armstrong said, “No wonder women fear birth.”

Yet, a historical perspective on childbirth suggests that birth should be less terrifying than in the past. Today, virtually all women and babies survive birth, with the birth of a child often an emotional high that many women and men report as being among the happiest of their lives.

How has American culture come to regard birth, a natural and intrinsic part of life and human society, with such trepidation, fear, and loathing? Armstrong suspects that the answer lies, in part, in a broader set of cultural

______________________________________

4This section summarizes information presented by Elizabeth Mitchell Armstrong, Ph.D., M.P.A., Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey.

shifts that have transformed modern society and in the evolution of what Beck (1992, 1999) calls a “risk society.” A risk society is one where the notion of risk overshadows all social life and where the identification and management of risk are the principle organizing forces. Beck (1999) argues that modern society has become a risk society “in the sense that it is increasingly occupied with debating, preventing, and managing the risks that it, itself, has produced” (Beck, 2006). As both Beck (1992, 1999) and Giddens (1999) argue, modern life is increasingly perceived in terms of danger and organized around the pursuit of safety. This increased awareness of risk has led to a pervasive sense of uncertainty and attempts to control the future.

Based on theories of risk articulated by Beck (1992, 1999) and Giddens (1999), Armstrong shared some insights that she deems relevant to risk assessment at birth. First, many of the risks being considered are what Beck calls “manufactured risks,” that is, risks created by human intervention, as opposed to risks created by weather or other natural events. Second, the omnipresence of risk in modern society has led to the emergence of a collective risk consciousness and a prevailing ethos of risk avoidance. Beck notes that much of this is organized around “attempt[ing] to anticipate what cannot be anticipated” (Beck, 2006). Third, the relationship between risk and trust is inverse; that is, science and technological expertise have become more important in society and at the same time the public has lost trust in both the content and conduct of science. Fourth, as Beck (1999) contends, some social actors have greater authority than others to define risk.

It is this fourth phenomenon, that some social actors have greater authority than others to define risk that leads to what anthropologist Brigitte Jordan calls “authoritative knowledge” (Jordan, 1997; Jordan and Davis-Floyd, 1992). According to Armstrong, Jordan argues that in any particular domain of human life there may be several knowledge systems or ways of understanding the world. Some of these ways of understanding may carry greater weight than others, either because they explain the state of the world better or because they are associated with a stronger power base, or for both reasons. As one kind of knowledge begins to dominate, other knowledge systems are delegitimized and dismissed (Jordan, 1980, 1997). For example, in his description of the evolution of American medicine, Paul Starr (1982) points to the tremendous “cultural authority” accorded one form of medical practice, allopathic medicine, to the exclusion of other forms of medicine that flourished in the late 19th century. The important thing to keep in mind about authoritative knowledge, Armstrong explained, is that it is socially constructed. Yet, it is viewed as being a natural order, with many people failing to recognize the ways it is socially constituted. In the realm of birth, obstetrics embodies authoritative knowledge. As such, obstetrics crowds out other ways of knowing and other ways of birth, limiting women’s awareness of alternative modes of birth.

When birth is viewed through this lens of a “risk society,” it is easier to understand the climate of fear, not confidence, that surrounds American birth and how it is that we think of birth as dangerous. Contemporary organization of maternity care reflects our “risk society.” According to Armstrong, Ray De Vries (2012) has noted that even our attempt to classify births into varying risk levels is itself a powerful reframing of birth, one that emphasizes the pathology inherent in birth, rather than the normal physiology of birth.

Another force shaping the way women perceive the risk of birth is the polarization (Declercq, 2012) in views of birth, which are often characterized as the medical versus midwifery models of birth. Different attributes are associated with the different models (e.g., pathology with the medical model, physiology with the midwifery model), with the two models often considered to be “diametrically opposed.” In Armstrong’s opinion, this polarization of views of birth not only obscures the fact that birth is a physiological process with the potential for pathology (i.e., it is not “either/or”), but also affects cultural perceptions of risk and structures the options available to women.

Women’s Views of Risk

Numerous sociological and anthropological studies of contemporary American childbirth demonstrate that women’s experiences of birth are marked by a range of sometimes contradictory feelings. Women express fear while putting emphasis on being safe or feeling safe. Additionally, both women and their providers voice varying levels of trust and distrust in the female body. Finally, the desire for control is paramount in many discussions of birth. Armstrong identified control and safety as being particularly important.

Control can have different meanings and different implications. In a qualitative study of women’s birth experiences, Namey and Lyerly (2010) documented the multiple meanings of control in the context of birth and concluded that control matters but its meaning varies widely among women and can have implications for their choice of birth setting. Armstrong said, for some women, technology-intensive birth in the hospital imparts a desired sense of control. But for other women, that same situation makes them feel out of control.

Safety too can have different meanings and different implications. The prevailing cultural view is that the hospital is the safe place to give birth. Indeed, in Armstrong’s opinion, most women trust modern medical care to ensure safe births. Yet, studies show that many women who birth in hospitals end up very dissatisfied with their birth experiences (Declercq et al., 2002, 2006). The very high rate of routine interventions is part of why

they end up so dissatisfied. A desire for safety drives many women’s choices to birth outside of a hospital. Precisely what historically sent women to the hospital to birth in the first place—a desire to avoid risks and to experience a safer birth—is what motivates some women to avoid the hospital for birth today. If women choose birth outside the hospital, it is not because they are reckless or heedless of risks. Rather it is because their understanding of risk and safety is very different.

A number of studies have assessed women’s decision making around home birth and have identified a common set of themes (Boucher et al., 2009; De Vries, 2004; Klassen, 2001). Some women choose home birth for religious reasons (Klassen, 2001). Armstrong speculated that perhaps the higher rates of home births in Pennsylvania and Indiana, which were evident on one of the maps shown by MacDorman, reflect the Amish populations in those states. Yet, even among women for whom religious beliefs are a primary motivation for choosing home birth, many of those women report some of the same ideas about birth that other women who choose home births for nonreligious reasons report. That is, they perceive home as being a place where they can feel in control and where they will feel safe. In addition to feelings about control and safety, trust appears to be another determinant of home birth choice. Women who choose home births often report that they trust their body’s ability to birth and that they have a deep level of trust with their care provider.

The Role of Structure

Debates about home birth typically do not consider a structural perception of risk. Yet, in Armstrong’s opinion, it is an important perspective to consider. That is, what systems support or impede women’s decisions about birth settings? By examining systems of transport and transfers, one can begin to see the ways that institutional arrangements can actually increase risks for low-risk women delivering outside the typical setting. According to Armstrong, numerous studies, as well as court cases, have demonstrated “the trouble with transport” (Davis-Floyd, 2003). In Armstrong’s opinion, that we have failed to develop a system of transport and transfer that protects women and babies from adverse outcomes is not just a failure of infrastructure. It is also morally fraught because of the deep polarizations that exist in thinking about birth (as physiology versus pathology) and because of deep levels of mistrust among provider communities. So not only do we lack the infrastructure for transport and transfer, we lack cultural consensus to develop that infrastructure and ensure its smooth functioning. Armstrong noted that in other societies where home birth is a viable option for women, most notably in the United Kingdom and in the Netherlands, systems have evolved for assessing risk and ensuring smooth transfer—thus

reducing risk and ensuring safety for women who choose to birth outside of the hospital.

Areas for Future Social Science Research

In conclusion, Armstrong identified several areas where social scientists can contribute to gaining a better understanding of birth settings. First, they can help to achieve a better understanding of the notion of “good birth.” What is a good birth? Where (setting) and how (under the care of which providers) can good births happen as often as possible? Second, they can help to achieve a better understanding of women’s decision-making processes (e.g., where do expectations of birth come from?) and ways to foster trust between women and maternity care providers. Finally, they can explore ways to change the structural landscape around birth and develop high-functioning systems of transport and transfer.

PRESENTATION ON ASSESSMENT OF RISK IN PREGNANCY5

By way of disclosure, Kathryn Menard began her talk by describing what she called her “vantage point.” She is the mother of three children and maternal fetal medicine specialist and educator; she works in a perinatal regional center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where about 3,700 babies are delivered annually. The center has a “24-7” midwifery practice that is well integrated into the care plan such that women can transition seamlessly from the midwifery practice to the generalist or maternal-fetal medicine practice. Many of her complicated antepartum patients choose midwifery-style births, with intrapartum care provided under the direct supervision of midwives but with physician backing. She noted that there is a freestanding birth center in town, just a couple of miles away from the hospital.

Why Assess Risk?

The purpose of risk assessment is to predict which women are most likely to experience adverse health events. The predictions can be used to streamline resources to those who need them most and avoid overuse of technology and intervention. Focusing resources on those who need them most and avoiding unnecessary interventions can lead to better care, better health, and lower cost.

When thinking about risk-appropriate perinatal care, it is important

______________________________________

5This section summarizes information presented by M. Kathryn Menard, M.D., M.P.H., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

to consider the entire continuum of care: preconception/interconception care (i.e., identifying modifiable risk factors and emphasizing prevention), antepartum care, intrapartum care, and neonatal care. Menard focused her comments on intrapartum care (care of the mother during labor and delivery).

Regionalization of Perinatal Care

Menard emphasized the role of regionalization within the context of perinatal care (care of the fetus or newborn from the 28th week of pregnancy through the 7th day postdelivery). In 1970, reports from Canada emphasized the importance of integrated systems that promote delivery of care to mothers and infants based on level of acuity; the reports showed that neonatal mortality was significantly lower in obstetrics facilities that had neonatal instensive care units (NICUs). In 1976, TIOP I (Toward Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy) described a model system for regionalized perinatal care that included definitions for varying levels of perinatal care based on both neonatal and maternal characteristics (March of Dimes, Committee on Perinatal Health, 1976). The early perinatal regional centers focused on education, dissemination of information, and referral resources and systems for maternal transport.

Evidence indicates that regionalization saves lives. For example, Lasswell et al. (2010) reported that infants smaller than 1,500 grams born at Level I or II hospitals had increased odds of death (38 percent versus 23 percent), compared to similarly sized infants born at Level III hospitals. Similarly, infants born at less than 32 weeks gestation in Level I or II hospitals had increased odds of death (15 percent versus 17 percent), again compared to similarly preterm infants born at Level III hospitals.

While the regionalization of systems, combined with advances in technology, has contributed to improvements in neonatal survival rates, there is not much information about other benefits of regionalized systems, including how regionalization impacts maternal mortality or morbidity. Nor is there much information about the potential harm of regionalization.

Early regionalization efforts emphasized both maternal and neonatal care. In 2012, the AAP issued a new policy statement regarding levels of perinatal care. The maternal characteristics that were included in the earlier policy statements (i.e., TIOP I) were removed, such that the policy statement contains no reference whatsoever to maternal care (Barfield et al., 2012). Likewise, the new Guidelines for Perinatal Care, 7th edition (AAP and ACOG, 2012), contains minimal reference to maternal care indicators. The current climate (2012) is also characterized by an emphasis on value-based health care, that is, an emphasis on increased quality at decreased

cost, an increased emphasis on patient-centered care, and greater recognition of a woman’s right to choose her site of birth.

What We Know About Neonatal Care in Different Settings

Menard remarked that while outcomes associated with different birth settings would be the topic of detailed presentations to follow, she wanted to provide a context for those talks (see Chapter 4 for a summary of that more detailed discussion). She mentioned the Wax et al. (2010) meta-analysis, which reported that planned home birth delivery of term babies is associated with less medical intervention but a two- to threefold increase in neonatal mortality. Data on delivery of term babies in freestanding birth centers is limited, so similar claims cannot be made. The Hodnett et al. (2012) Cochrane review reported that delivery of term babies in alternative hospital settings, that is, colocated midwifery units, are associated with higher rates of spontaneous vaginal delivery, more breastfeeding, more positive views of care, and no difference in either neonatal or maternal outcomes (all compared to conventional hospital settings). That review was based on 10 randomized controlled trials (N = 11,795). Finally, with respect to the delivery of term babies in a hospital setting, Menard mentioned Snowden et al. (2012), who reported that a higher delivery volume may be associated with lower neonatal morbidity. Very little is known about collaborative care models within the hospital environment and whether such models impact either neonatal or maternal outcomes.

What We Know About Maternal Care in Different Settings

Because maternal mortality is an uncommon event, examining maternal mortality is like “looking at the tip of the iceberg,” in Menard’s opinion. And while severe maternal morbidity is an active area of conversation today, it is not measured in a consistent manner. Much of the conversation revolves around how to define and monitor severe maternal morbidity. Nor are factors that predict the need for a higher level of care well defined. The scientific basis for making those decisions is limited, with different predictors being used in different circumstances.

“Low Obstetric Risk”

Different researchers define “low obstetric risk” differently. Menard gave four examples. First, in a randomized trial conducted in Australia (the COSMOS trial) on primary midwifery continuity care versus usual care within a tertiary care center, McLachlan et al. (2012) used these inclusion criteria: singleton, uncomplicated obstetric history (no stillbirth, neonatal

death, consecutive miscarriages, fetal death, preterm birth <32 weeks, isoimmunization, gestational diabetes), no current pregnancy complications (e.g., fetal anomaly), no precluding medical conditions (no cardiac disease, hypertension, diabetes, epilepsy, severe asthma, substance use, significant psychiatric disorder, BMI >35 or <17), and no prior Cesarean.

Second, in a randomized controlled trial of simulated home birth in the hospital (midwife-led care) versus usual care in the United Kingdom, MacVicar et al. (1993) used very different inclusion and exclusion criteria: nulliparous6 and multiparous7 women were included, but women with prior Cesareans were not; their definition of exclusionary maternal illness was more loosely defined (“no maternal illness such as diabetes, epilepsy, and renal disease”); and, while their definition of past obstetrical history was not as specific (no prior stillbirth, neonatal death, or small for gestational age), they included a history of elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein.

Third, Bernitz et al. (2011) used yet another set of inclusion and exclusion criteria in their randomized controlled trial of three hospital levels in Norway. Their inclusion criteria were healthy, low-risk women without any disease known to influence pregnancy; singleton; cephalic; BMI <32; smokes <10 cigarettes/day; no prior operation on the uterus; and 36 weeks, 1 day to 41 weeks, 6 days gestation. Finally, a randomized controlled study in Ireland on midwifery care versus consultant-led care (Begley et al., 2011) used yet another entirely different set of exclusion criteria (e.g., BMI <18 or >29; smoking ≥20 cigarettes per day).

Menard emphasized the need for consistent and evidence-based criteria of “low obstetric risk” so that valid comparisons across settings can be made and our understanding of birth settings advanced.

Research Needed to Describe “Risk”

In addition to developing uniform definitions of risk factors, several other research steps need to be taken in order to advance our understanding of risk. Menard called for a greater understanding of essential resources for each of the various birth settings, predictors of neonatal complications to guide decisions about level of neonatal care (i.e., predictors beyond the context of birth weight, which is how most current neonatal care criteria are based), predictors of maternal complications to guide decisions about level of maternal care, and predictors that should prompt maternal transport.

With respect to determining predictors of maternal care, Menard remarked that the concept of levels of maternal care (i.e., birth center versus Level 1 [basic] versus Level 2 [specialty] versus Level 3 [subspecialty] versus

______________________________________

6A woman who has never given birth.

7A woman who has given birth two or more times.

Level 4 [regional perinatal center]) is being developed and promoted as a strategy to expand regionalized perinatal care. Ideally, the strategy will be applied uniformly across all states so that surveillance can be standardized. But doing so, she opined, will require a complementary set of predictors of maternal complications to guide decisions about which level of care a woman should receive.

With respect to predictors that should prompt maternal transport, the question is, if a woman has a birth experience in a birth center or a facility with a lower level of care, what are the important signs and symptoms that indicate she should be moved to a higher level of care?

Menard identified several additional research topics that would help to define “risk”: uniform definitions of maternal and neonatal morbidity; definitions of family perceptions and satisfaction with care; the role of the care provider and the role of continuity of care; the role of the care “system” and how to optimize that system (i.e., interprofessional working relationships, consultations, hand-offs, transfer of care); cultural issues, such as threshold for intervention in high-level facilities; and patient perception of risk and the influence of her perception of risk on birth outcomes and perception of care.

DISCUSSION WITH THE AUDIENCE8

Following Menard’s presentation, the workshop was opened to questions and comments by members of the audience. Topics addressed included international birth setting trends and risk guidelines; perception of risk among women entering pregnancy and how it varies depending on age, culture, and other factors; the large proportion of non-Hispanic black women who deliver unplanned out-of-hospital births; the increasing rate of home births in the United States; how economic factors drive birth setting decisions; the need for infrastructure in states without birth center regulations; and the challenge of transfer (legal and professional mistrust issues).

International Birth Setting Trends and Risk Guidelines

The audience raised two separate sets of issues related to birth setting assessment outside of the United States. First, it was suggested that there might be lessons to be learned from antepartum risk guidelines being used in the United Kingdom, including the fact that the guidelines were created by conducting a systematic review of the international evidence and reaching consensus among a stakeholder panel.

______________________________________

8This section summarizes the discussion that occurred at the end of Panels 1 and 2, immediately following Kathryn Menard’s presentation.

Second, a remark was made about the increasing percentage of women in the Netherlands who are choosing hospital deliveries. Specifically, according to a workshop participant, the number of women in the Netherlands choosing hospital deliveries has increased from 23 to 38 percent over the past 20 years. The participant emphasized that this is very different than what is happening in the United States, where a growing percentage of women are seeking home deliveries. He also emphasized that the trend is occurring in a country, the Netherlands, with a long history of home births. “I want the record to show,” he said, “that [in the Netherlands] it is considered a privilege to have a hospital birth.” Elizabeth Armstrong agreed that, yes, more women in the Netherlands are seeking hospital births, but she warned that the reasons for the trends are complex and that the trend does not necessarily mean that women feel unsafe in home birth settings. Another participant who identified herself as being from the Netherlands agreed with Armstrong that the reasons for the increasing trend in hospital births are complex. They include demographic changes, that is, more older women entering pregnancy, as well as more primips; media portrayal of pregnancy as something to be feared; increased prenatal testing; and a diverse immigrant population, with varying cultural perceptions of pregnancy. She noted primary care in the Netherlands is midwife-led care, adding that the rate of home birth in the Netherlands is about 19 percent, with another 12 percent of women giving birth in a hospital but with their midwives and without attendance by obstetricians.

Perception of Risk and How It Varies Depending on Age, Culture, and Other Factors

A participant suggested that perception of risk might be changing as the percentage of older women entering pregnancy increases. The implication was that older women are not as healthy as younger women and therefore may perceive pregnancy as a riskier experience than younger women do. Kathryn Menard agreed that women entering pregnancy are less healthy than in the past because they are older and suggested that perhaps the increasing maternal morbidity and mortality trends being observed in the United States are related to that demographic change. She emphasized the importance of maternal morbidity and mortality surveillance.

More generally on the issue of perception of risk, Nigel Paneth observed, “The question about risk is always: what can you control?” Centuries ago, losing a child in infancy was considered normal and unpreventable. Changes in infant (and maternal) mortality over time have changed what women consider as unpreventable, or uncontrollable. For example, the likelihood of a woman dying during pregnancy dropped 100-fold during the

20th century. Today, the risk of a woman dying during pregnancy is more controllable than it was in the past.

An audience member commented on the role of culture and how a woman’s perception of risk might reflect her own place of birth. Armstrong replied that, while there has not been much research addressing the role of place of birth in perception of risk, women who have experienced other maternity care systems enter the U.S. system with a certain set of expectations. This is true even of primips who have not actually delivered themselves but nonetheless have an understanding of how birth works in the culture they come from.

Armstrong further observed that social disadvantage can also impact choice of birth setting. Some socially disadvantaged women, whether it is because of race or ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or immigrant status, perceive medicalized, high-technology hospital birth as being of a higher status and therefore more desirable than home birth. That perception is not necessarily related to risk or safety.

Disparity in Outcomes Among Ethnicities

The panelists were asked why as many as 66 percent of home deliveries by non-Hispanic black women are unplanned and what research is needed to find the answer(s). Marian MacDorman clarified that the incidence of home births in general is much lower for non-Hispanic black women, perhaps because fewer non-Hispanic black women have access to care providers that allow that option, and that the proportion of unplanned home births is high but the absolute numbers are low. With respect to research, she emphasized the importance of directly asking women about their preferences and experiences. She also suggested promoting more services in areas and neighborhoods where non-Hispanic black women live and training more minority care providers.

Another audience member speculated that at least some of the large percentage of African American women who report on birth certificates that their home birth was “unplanned” reflects a growing preference in free birthing, which is birthing without the assistance of a care provider. She noted that free birthing is on the rise in places like Maryland where Medicaid provisions for home birth have been removed, and that many women who choose free birthing report “unplanned” on their birth certificates because they think it will draw less attention.

Paneth observed that the “big monster in the room” is not that 66 percent figure, rather the “huge health disparity between black and white infant mortality.” That, in his opinion, is the greater research challenge. What is causing such extreme preterm birth among African American women? While many research teams are pursuing answers, the question remains.

Why the Percentage of Home Births in the United States Is Increasing

The panelists were asked to reflect on why the percentage of home births in the United States is increasing. MacDorman replied that birth certificate data do not reveal why certain birth options are chosen, or not chosen. She referred to the large number of studies in the medical literature based on having directly asked women why they chose home births. Women who choose home births express desire for low-intervention physiologic births in environments where they feel comfortable and more in control over which interventions will be induced, and they express concern about the high rates of Cesarean delivery and other interventions in hospital settings.

Another audience member asked whether there might be a correlation between change in percentage of home births and increased access to licensed midwifery offering the option of transfer. That is, do states exhibiting greater increases in percentage of home births provide greater access to licensed midwifery offering the option of transfer? MacDorman agreed that the question would serve as an excellent topic for future research.

Economic Factors Driving Birth Setting Choice

An audience member commented on the role of health insurance in birth setting choice and observed that a significant number of women who would choose to deliver outside of the hospital are not able to do so because their insurance will not cover out-of-hospital deliveries. The audience member also mentioned liability insurance and observed that in some states Medicaid will not cover a home birth midwife unless the midwife carries a level of liability insurance that most home birth midwives do not carry. Panelist MacDorman agreed that economic factors contribute to the complexity of the issue of choice. She remarked that studies have shown that the cost of a home birth is about one-third the cost of a hospital birth, but in fact home births cost women much more than hospital births if they are not covered by insurance.

The Need for Infrastructure in States with Birth Center Regulations

In response to remarks made by Nigel Paneth about a birth center in Michigan closing after a breech delivery, an audience member commented on the fact that Michigan is one of the few states without licensure for freestanding birth centers. Breech deliveries are outside of the national standard for birth centers. The implication was that states without regulations, such as Michigan, need infrastructure to help avoid this type of problem.

The Challenge of Transfer

A participant observed that transfer is legally fraught for liability reasons. For example, in Virginia, midwives are licensed and practice legally. Yet, some hospitals report each and every transfer to the state licensing board, which presents a real challenge for the midwives. She asked the panelists if any of their research points to a way forward. Armstrong added that the patchwork of state laws that govern who can attend births compounds the legal challenge. However, she cautioned that moving forward will require more than legal reform. Addressing the challenge of transfer will require a multipronged approach, one that also involves rebuilding trust among the different communities of care providers. She described the mistrust that currently exists among communities of care providers as “endemic and corrosive.” MacDorman agreed that trust is a core issue.

Two other participants echoed concerns about liability and the important role that state legislation plays in either restricting or promoting collaboration during transfer. For example, malpractice carriers telling physicians that they cannot provide midwifery backup significantly restricts collaboration. The state of Washington has been very forward thinking in its requirement that insurers who provide malpractice insurance provide such insurance to midwives, thereby promoting collaboration.

This page intentionally left blank.