Panel 1: Implementing Attributes of a Health Literate Organization

Medical Director and Cofounder, Shared Care Free Clinic Jackson County, Missouri

The following is a summary of the presentation given by Bridget McCandless. It is not a transcript.

The Shared Care Free Clinic in Jackson County, Missouri, cares for adults who are uninsured, whose incomes are below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, and who already have a diagnosed chronic illness. This population is most likely to need medications, and one of the strengths of the program is that the clinic is able to provide people with necessary medications. Education levels for the clinic’s patients range from third grade to college degrees, although the average level of education is high school. The patients generally have complex multiple chronic illnesses, and 72 percent take six or more medications. The one thing that the clinic’s patients have in common is that they are going through hard times, said McCandless.

Effective communication is an issue for patients at the Shared Care Free Clinic, especially because complicated ideas about conditions and treatments are being conveyed to people who often have low health literacy. Health literacy, for those working at the clinic, is defined as “understandable and two-way communication about wellness and illness for you and those you care about,” which helps ensure that the two-way

aspect of communication is not forgotten. McCandless said she believes that the most important message is not the message at the end of the visit but rather the tone and style of interaction established from the beginning, which encourages patients to be receptive to the messages at the end of the visit.

Knowing about the patient’s living environment is very important, according to McCandless. For example, the provider needs to know about special circumstances, such as whether the patient lives in a car, because it is very difficult to manage insulin levels when living in a car. Does a patient have access to refrigeration, a telephone, and a stable place to live? These things have to be taken into account to be sure that information given to a patient is relevant to his or her circumstances. The patient’s emotional state is also very important, regardless of his or her education level. When an individual is stressed or tired, he or she is less able to receive and understand information. Providers must communicate differently with those patients.

One of the greatest needs at the clinic, McCandless said, is to simplify complex patient regimens and to segment the treatment plan into smaller pieces that a patient could process a little bit at a time. Sometimes providers are concerned that a patient may not return, so their tendency is to give too much information at one time. A treatment plan for diabetes (see Box 2-1) shows how much is expected of a patient. McCandless noted that it would be difficult for her patients to find time for a regular workday after complying with the treatment regimen.

A clinic team composed of the director of the clinic’s medication program, the front office clinic coordinator, and McCandless worked on simplifying complex regimens and developing treatment plans to help patients adhere to intensive lifestyle interventions and increase their abilities to engage with health care providers. The team also included four patients who acted as advisers.

The clinic serves a population that can be shy when dealing with a physician because of the substantial wealth and power differential. This differential needs to be taken into account when setting goals for providers and patients as they engage in the new approach to treatment. The goals for providers are to simplify vocabulary and promote recognition that style and demeanor affect the progress of the patient. One of the challenges in reaching these goals is giving constructive feedback to physicians, particularly when they are volunteers. The clinic does not have any tools to enforce behavior change among providers and must rely on their willingness to volunteer.

The goals for the patients are that they know and understand their diagnosis, that their understanding of and adherence to medication improves, that they feel they can ask questions, and that they come pre-

BOX 2-1 Diabetes Treatment Plan

Get up after 8 hours of sleep

Brush and floss your teeth

Shower and check your feet

Check your sugar and write it down

Take insulin and other morning medications

Eat a balanced breakfast

Check 2-hour postprandial (PP) glucose

Do your meal planning

Grocery shop

Check sugar and record

Eat a balanced lunch and take insulin

30 minutes of aerobic exercise

Prepare a healthy dinner

Check your sugar and write it down

Check 2-hour PP glucose

Practice stress reduction techniques

Take bedtime insulin

pared for office visits. McCandless said that preparation for the visit was a concern, because often patients had not given any thought to what they needed from their time with the physician. In response to this concern, the clinic staff developed some tools to help patients be better prepared.

The first tool used in the new approach to treatment is a notebook, which every patient is given. On the front of the notebook is information about how to reach the patient’s provider. Even more important, McCandless said, is that inside the notebook is information about patient responsibilities, provider responsibilities, and how to use the notebook. The patient’s job is to ask questions; take medicines and call if there is a problem with them; and do his or her best with following the diet and being active. The provider’s job is to give good explanations about the patient’s condition, medicine, and blood tests; be available to give good advice; and help the patient be successful. The notebook helps alleviate the problem of patients leaving without their instructions. Prior to using these notebooks, patients would frequently leave their instructions at the front desk, in the chair on the way out, or somewhere else in the clinic. The notebook gives patients a place to keep their notes together.

The notebook also serves as a place for written instructions. McCandless said that she and a patient negotiate together what changes the patient will

work on before the next visit and record them in the notebook. Treatment changes can also be recorded. This approach assisted in identifying a major problem—patients did not understand why medications were stopped, which can be more crucial information than why a medication was added. That information is now recorded in the notebook and is important both to help the patient adhere to the medication plan and to inform the next provider who sees the patient.

Another strategy used at the clinic is to choose the most important pieces of information to communicate to the patient. McCandless said she found that patients will read only one piece of paper. As a result, almost all patient education material at the clinic has been shortened to one page. In addition, providers are using the teach-back1 method, so that now, following a discussion, the patient explains to the provider in his or her own words the treatment plan and how to accomplish it, and agrees to the plan.

McCandless explained that at the clinic they have had to change their perspectives on patients’ illnesses to match those of the patients themselves. She said that the population served by the clinic does not plan on a 30-year horizon. Rather, they exist in a 2-week cycle that revolves around paychecks. For example, instead of discussing the long-term effects of diabetes, such as amputations and blindness, McCandless said that she has found greater success in discussing short-term effects, such as infections, because these things have an immediate impact on patients’ lives. An infection means that a patient cannot go to work the next day.

Teach-back becomes more than a tool for understanding; it also forms a social contract, a promise, between patient and provider. It is not just that the patient understands what he or she has been told but also that the patient agrees with the plan and sees the relationship with the provider as a partnership.

With this health literate approach to treatment, the clinic’s patients now have exceptional adherence rates to very complicated treatment regimens. They have a much higher rate of screening than patients with health insurance. The clinic’s diabetes and hypertension outcomes are better and, most important, patient medication adherence is exceptional. At the clinic, patients are instructed when they come in that if they have any questions or if they decide they need a change in their medication, they should call their provider. This practice has been very helpful, McCandless said.

_______________

1 “Teach-back is a way to confirm that you have explained to the patient what they need to know in a manner that the patient understands. Patient understanding is confirmed when they explain it back to you” (http://www.nchealthliteracy.org/toolkit/tool5.pdf [accessed June 3, 2013]).

Another successful mechanism implemented to encourage patients to engage in their care and with their provider is the patient preparation sheet. The sheet, which was designed by staff in collaboration with patients, gives the patients something to think about while they are waiting for the provider. Some examples of questions and statements are as follows: “Are you having a hard time taking your medication?” “What is it that you need in patient education?” “I am having difficulty with this part of my care plan.” McCandless said they have found that the most important statement for sparking conversation and learning what is happening in people’s social lives is “I have exciting news to share.”

When the form was created, the questions and statements were numbered, but patients were answering only the first question. When asked why, one patient said, “I cannot believe you are giving me a test!” The numbers were intimidating to patients. Once they were removed from the form, people began to fill it out completely.

Terminology can also get in the way of good communication with patients. McCandless related an anecdote that while making rounds with her team, she mentioned that one patient probably had Graves’ disease. On returning to the patient, McCandless found her in tears. The patient said that she could not believe her provider told all of those people that she was going to die and go to her grave. So, McCandless noted, even words that one thinks are benign can cause trouble. This was a lesson in the importance of hearing through the patient’s ears.

One strategy that has worked at the clinic is to put students in the room with providers and ask them to grade the providers on how well they communicate with the patient. This invests everyone in modeling good behavior, and the students learn language and listening skills, so it is win-win. The students are asked if the encounter passed the “grandma test,” that is, could your grandmother have understood the directions?

All the forms at the clinic were reviewed to determine their helpfulness to patients. The feedback received from patients was that it was not the form that was a problem, but the lack of explanation as to why the information was necessary. Patients wanted an explanation on every single page. For example, they wanted to know why they were asked for demographic and financial information and how this information would be used. McCandless noted that when dealing with a vulnerable population, it is important to provide those explanations. She then showed a copy of the clinic’s HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) consent form, which is one page long. She said that it was taken from the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse with its permission, and she recommends looking to outside sources for helpful ideas and information.

One idea that did not work well, McCandless said, was putting

together a patient advisory committee that included only the patients with the strongest literacy skills. The patients would give good grades and approve all the forms. So, McCandless said, she took the forms to her most marginal patients and asked, “Does this picture make sense to you?” and “Does this form have too many words?” A clean copy would not produce any feedback, but when the form was already marked up, she would get a better response from the patients.

Volunteers are a great blessing to an organization like the clinic, but they can also be a challenge to implementing organization-wide efforts. First, because volunteers are not present all the time, the clinic needs to reinforce the message of health literacy. Therefore, the day after they volunteer, the providers are sent a reminder. The reminder lists the health literacy efforts the clinic expects them to make while there and asks for feedback. So far, this method has worked well.

Measuring success is always a difficult thing, McCandless said. The clinic has been tracking diabetes, hypertension, and asthma outcomes for the past 10 years. There has not been a substantial change in numbers, but there has been great receptivity from the patients. The clinic has done well on pre- and post-care surveys. It has seen an improvement in communication skills in its post-care surveys. McCandless noted that it is always difficult when changes are made to an entire organization. It is hard to know which changes are attributable to health literacy and which are attributable to doing a better job with medicine. McCandless said she believes health literacy is an integral part of the clinic’s hypertension and diabetic messaging.

To promote sustainability of the changes, the clinic has embedded teach-back in the provider progress notes, so that every time a provider leaves the room, he or she has to check off that teach-back was performed and that the patient received written instructions. McCandless noted that it is important to make sure something is recorded in a patient’s notebook because it is a reward to the patient for remembering to bring the notebook to every visit. Sometimes, McCandless said, all she writes is “great job” or “I love that you quit smoking.”

McCandless concluded by saying that she thinks that teaching people about language will always be sustainable. She believes that it is like a physical examination scale or differential diagnosis scale—that is, when health literacy becomes embedded in the entire program, it is easy to sustain.

KAREN ROGERS, M.S.N., R.N.-B.C.

Director of Education Western Maine Area Health Education Center, Franklin Memorial Hospital

The following is a summary of the presentation given by Karen Rogers. It is not a transcript.

Franklin Memorial is a small community hospital in west-central Maine with about 50 beds and 14 office practices. The hospital’s coverage area is about 1,000 square miles, but the population is only 29,000. The population is not racially or ethnically diverse, but a large segment of the population has low socioeconomic status. The hospital’s health literacy steering committee has six consistent members who include occupational therapists, social workers, behavioral health specialists, the Health Community Coalition, physician’s assistants, nurses, and, occasionally, physicians. For certain projects, the team also includes representatives from the hospital lab, billing, radiology, facilities, and maintenance. The team has focused on general awareness, environment navigation, and patient education and has developed a literacy volunteer program, implemented teach-back education, and instituted plain-language document preparation.

Rogers said that her organization exhibits most of the attributes of a health literate organization. First, there is great support from the hospital’s leadership. Rogers is the director of the education department and is given wide latitude in her duties. In addition, the hospital’s leadership recognizes that health literacy has an impact on the financial bottom line. Any intervention that helps to prevent readmissions will save the hospital money. Health literacy efforts also help Franklin Memorial compete with other hospitals. Maine has some of the highest-rated hospitals in the nation, and patient satisfaction and hospital quality are areas where hospitals are competitive. Because Franklin Memorial is competing in a high-level group, its leadership is supportive of health literacy activities.

Rogers’s team conducted an organizational assessment and found that only 15 percent of the clinical staff used the teach-back method. After training, participation is 66 to 89 percent, with the best performance occurring in obstetrics and physical rehabilitation because the method is well integrated into those systems. There is also a program for emergency medical services in the community that calls patients and follows up with them at home. They also use teach-back and follow through to make sure that what patients learned in the office is carried on in the home setting as well. Rogers’ team prepares the workforce by teaching awareness and

education about health literacy and how it impacts patients, the hospital’s bottom line, and hospital workers’ jobs.

Health literacy efforts at Franklin Memorial involve various strategies, many of which are free and available online, such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit.2 The hospital is focusing on overall patient safety, safety with medication, and its core measures.3 Rogers noted that another accomplishment is a patient education policy, which is revised every 3 years and is based on what the hospital has learned from prior years’ experience.

The hospital has a very large volunteer population. Most of the volunteers are elderly, and the hospital has a system in which individuals can pay off their hospitals bills by volunteering their time. Volunteers can also bank hours toward future medical bills for themselves or their families. The volunteer workforce is 25 percent of the size of the paid employee workforce, and it is very useful for testing health literacy and patient education materials. The hospital also has incorporated chaplains and groups of chaplain students into the health literacy program because these individuals have a great deal of patient contact.

Rogers noted that the hospital, which includes the only behavioral health services unit in the area, has a large population of patients with mental health needs. The health literacy team works to include this population in its focus groups for testing materials.

High-risk topics the health literacy team has chosen to address include congestive heart failure (CHF), medications such as anticoagulants, diabetes, stroke, and certain procedures. CHF is of great interest because of the penalty imposed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services if patients are readmitted within 30 days of their release from the hospital’s care. The team searched for existing programs and materials that were health literate but often had to develop their own. The team has been learning more about plain language and teaching others in different departments to prepare letters to patients, for example, letters about how to access services and information by phone. Nevertheless, legal issues can be a barrier

_______________

2 The AHRQ “toolkit is designed to help adult and pediatric practices ensure that systems are in place to promote better understanding by all patients, not just those you think need extra assistance. The toolkit is divided into manageable chunks so that its implementation can fit into the busy day of a practice” (http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit [accessed June 3, 2013]).

3 Core measures were developed by The Joint Commission. According to the Baylor Health Care system, core measures “have been shown to reduce the risk of complications, prevent recurrences and otherwise treat the majority of patients who come to a hospital for treatment of a condition or illness. Core measures help hospitals improve the quality of patient care by focusing on the actual results of care.” See http://www.baylorhealth.com/ABOUT/FACTSSTATS/QUALITYDATA/Pages/Default.aspx (accessed June 3, 2013).

to using plain language to create documents and forms, especially consent forms. In addition, user testing is an important and ongoing activity.

Bills are a major source of patient dissatisfaction because, Rogers said, they are difficult for patients to understand. The health literacy team is working on a better way to format bills and to explain charges, payment options, and Medicare coverage. Rogers’ team has also worked on improving ease of navigating the hospital environment. Finding that many people were getting lost in their system, the team conducted a “secret shoppers”–type exercise, sending people to various parts of the hospital to see if they could find their way. One problem discovered by the team was that signage was not consistent. For example, if a patient needed an X-ray, he or she had to have a prior understanding that “radiology” and “computed tomography (CT) scan” meant “X-ray,” because the hospital’s signs used all those terms. There were also no icons on the hospital signs, making it difficult for patients with low literacy skills to find even the cafeteria. These problems were corrected.

The team used patient tracer methodology4 to evaluate the patient’s experience from the time he or she arrives on the hospital campus through the duration of the stay. For example, the team asked, do patients know where to park? The hospital has elderly patients walking all over a large campus, getting lost and tired and not knowing where to go. The team worked on signage and followed the patients from the entrance of the hospital to the office practices, discharge, and billing. The team looked at every area the patient might be visiting, Rogers said.

As part of a patient education campaign, the team created a library-on-wheels program to provide needed information resources. Eight portable carts with computers are now available for use. Staff can show patients how to surf the Internet and where to find useful, valid, and reliable information. The carts also allow nurses and certified nursing assistants to show a DVD of patient education material.

Rogers said the team conducted needs assessments, implemented the teach-back method, evaluated the videos used, and conducted many education sessions. Assessments showed, for example, that in teaching about medications, the staff was strong in imparting knowledge such as what a medication was for, but was weak in communicating why it was important to take the medications. The staff did well in teaching certain skills, such as how patients should weigh themselves, but did less well

_______________

4 Tracer methodology allows for the evaluation of an organization’s continuum of care, infection control, and medication management, among other things. Tracer methodology calls for the use of “surveyors” who select active patients and trace their progress and care through departments or services of the hospital or care organization. See http://www.hcmarketplace.com/supplemental/6209_browse.pdf (accessed June 4, 2013), p. x.

in teaching patients how to remember to do it every day. The facility has since implemented and been using questions from the Ask Me 3 program.5 Rogers thinks of “ask” as an acronym standing for “attitude, skills, and knowledge.” It is easy for the nurses to remember and has been easy for them to continue teaching. Rogers said the team also has done quite a lot of work with the hospital lab because during their education programs they found that there were a lot of recalls and refusals of samples. The office practices were not giving patients who needed laboratory tests the correct information. By following through on different departments’ issues, Rogers said, her team ended up teaching more than 400 people in the organization about health literacy.

Rogers said that the health literacy team found a good book on CHF from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that they initially reviewed with patients and gave them to read. However, they found that this was not the best approach because the patients would look at it once and never again. To get patients to use the book as a reference, they decided, with permission from the author, to take the pictures out of the book and make a one-page plan that was more effective for reinforcing the concepts the patients needed to know. One of the physicians actually used the one-page sheet for a research project. Keeping information to one page has worked extremely well and has been the most important thing that the hospital has done in CHF education, Rogers said.

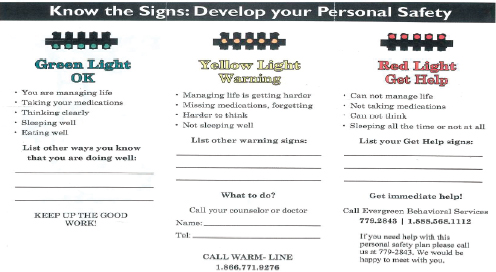

The hospital set a goal to decrease emergency department admissions for mental health patients by getting them help earlier, Rogers said, and the health literacy team is working in this area. Figure 2-1 shows the material the hospital is using to prompt people to seek help at the first sign of trouble. The team had created the material with input from patients, their families, and hospital staff.

Interest in health literacy has been generated in several hospital departments by health literacy audits. The departments want to hear about problems such as missed appointments, noncompliance, readmissions, repeat labs, and issues with the learning management systems. If the departments do poorly on a health literacy audit, they work hard to improve, she said.

Rogers said that the organization’s attempts to integrate health literacy into other programs are under way. For example, health literacy was integrated into a customer service program that was already being

_______________

5 Ask Me 3 is a patient education program with the goal of improving provider–patient communication. The patient is encouraged to ask these three questions of their health care providers: What is my main problem? What do I need to do? Why is it important for me to do this? See http://www.npsf.org/for-healthcare-professionals/programs/ask-me-3 (accessed August 1, 2013).

FIGURE 2-1 Emergency mental health form.

SOURCE: Rogers, 2013.

implemented. Health literacy has also been hardwired into clinical and information technology (IT) documentation. The team is currently working on a health literate approach to reduce smoking among the Medicaid population.

Rogers also noted that the Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS)6 provides patient satisfaction scores for physicians on how effectively they communicate. This is an incentive for physicians to engage with health literacy. In addition, the organization is further engaging leadership by continuing with their interdisciplinary team collaboration. Franklin Memorial is also collaborating with the Geriatric Education Center at the University of New England and with four other teams in the state to share ideas and combine initiatives.

One barrier the health literacy efforts have confronted is an entrenched way of thinking or acting. For example, physicians resist health literacy tools because they do not see teaching as part of their role but rather as that of their medical assistants. Rogers and her staff tell these physicians that explaining and obtaining consent is also a teaching role. Provider acceptance of health literacy efforts varies and is an area of continuing work.

_______________

6 CG-CAHPS is a tool developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that measures the patient’s perception of care.

Other examples of entrenched thinking can be found in both the marketing and legal departments. Although the marketing department has received some training in health literacy, it continues to produce materials with shadowing, complicated fonts, and formatting that is difficult to read. There has also been resistance to simplifying consent forms. Rogers said that occasionally the nurses will say that they don’t have time to teach, but, from the organizational perspective, part of the nurse’s role is to find and take advantage of the teachable moment.

Rogers noted that trust is very important and is something that the hospital works to build between patients and staff. The health literacy team has also been working with hospital employees, people who work in the kitchen, in maintenance, and in the laundry. Many of them have low health literacy, and the organization has been reaching out to them in a learning management system, making use of plain language to convey information. For example, health literacy is integrated into hospital orientation programs, so every new employee learns about the importance of health literacy. Teach-back has been hardwired into the hospital’s electronic records. Rogers said that they have also developed a reading coach program with hospital volunteers. The volunteers have been trained in literacy programs, and they serve as reading coaches to help people complete their forms and refer them to literacy programs if necessary.

Other health literacy efforts include working with dental and other practices in the community. Because the hospital and the other practices share the same patient population, it is beneficial to include everyone, from dentists to nursing homes, in the health literacy effort.

Hospital policies need to be updated every 3 years, Rogers said, and this provides an incentive to review and update information. Some financial support for patient education materials has been received from the local Oddfellows group, which donated money specifically for patient education.

Health literacy efforts at Franklin Memorial have been under way for 6 years, and there has been a shift in culture. The nurses and medical assistants have adopted teach-back communication, even among themselves. The hospital has begun to use plain language even for other types of training, such as fire safety.

The hospital’s accreditation requirements and rating systems make health literacy necessary and are additional incentives to support and sustain health literacy efforts. Rogers concluded by saying that the rules changes for Medicare and Medicaid are making health literacy even more important, thereby adding additional incentives to continue to work on this issue.

Director, Center for Advancing Pediatric Excellence Carolinas HealthCare System

The following is a summary of the presentation given by Laura Noonan. It is not a transcript.

The Carolinas HealthCare System is one of the nation’s largest public not-for-profit health care systems, with close to 60,000 employees, 38 hospitals, 7,500 licensed beds, and 900 care locations. It serves more than 3 million patients and has more than 9 million patient encounters each year. The system continues to grow. It began as a single community hospital that was also an academic hospital with community-based residency programs and a strong educational component. Now it has developed into a fully integrated health care delivery network, working to deliver value in three important ways—through patient experience, through high-quality outcomes and delivery processes, and through cost savings and efficiency. However, she noted, achieving success is a journey for any organization.

Noonan explained that her presentation would describe the Carolinas HealthCare System’s health literacy efforts while answering five questions:

- What generated interest in improving health literacy?

- What general strategies did you use to move health literacy forward?

- What factors facilitated implementation of changes to improve health literacy?

- What factors were barriers to implementation of changes to improve health literacy?

- How will the implementation of changes to health literacy in your organization be maintained over time?

In answer to the first question, Noonan said that in 2009 the new chief medical officer at the system level, Roger Ray, recognized the role of health literacy in patient safety and outcomes. He created a task force of experts, including roundtable member Darren DeWalt, to build a case and persuade the hospital governing board of health literacy’s importance. Noonan was asked to chair the task force, not because she was an expert in health literacy but because the system’s leadership wanted to use an improvement science framework and data-driven change.

Over the next year, the task force designed a change package. This effort coincided with the development of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) toolkit, which was incorporated into the system’s work. The task force identified three drivers: (1) patient com-

munication, (2) provider education, and (3) patient experience, which included more than just patient satisfaction. The task force was involved in testing the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit in one of the system’s clinic settings.

To answer the second question concerning strategies to move health literacy forward, Noonan said the first thing the task force did was create a collaborative. They used an Institute for Healthcare Improvement7 collaborative model that used learning sessions to bring teams together. Teams from 25 facilities across two states participated in two face-to-face learning sessions with action periods, and communication occurred between sessions with coaching, content experts, and improvement science experts. Work centered around data-driven change.

The teams’ immediate goal was not implementation. Noonan said that, in her view as an improvement science expert, implementation is at the end of the journey rather than the beginning. The facility teams used quality improvement methodology to test and use data in order to determine which ideas worked and which did not. The teams had to commit and submit their monthly data on a regular basis, and the data were used to provide feedback and drive the improvement. A customized database was built to manage monthly data reporting.

The learning sessions included work prior to the session. During the sessions, there were health literacy expert presentations and use of quality tools and improvement methodology. The process allowed flexibility of specifics depending on local conditions and each site’s strengths and opportunities. During action periods, teams communicated using conference calls, monthly reports, an online content and document management site, and a listserv.

Noonan said that a collaborative dashboard with run charts8 was used to indicate whether the facility teams were making improvements and achieving their goals. Using such a format is often helpful for seeing the interactions between efforts. One of the goals involved the use of teach-back. The goal was not only to train staff in the use of teach-back but also to observe them using the method. Over time, the teams increased the use of teach-back and surpassed the goal of successful use of teach-back 75 percent of the time. Noonan noted that the teams were also able to increase the successful use of Ask Me 3 to more than 75 percent. Never-

_______________

7 “The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), an independent not-for-profit organization based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a leading innovator in health and health care improvement worldwide.” See http://www.ihi.org/about/Pages/default.aspx (accessed June 3, 2013).

8 “A run chart is a line graph of data plotted over time. By collecting and charting data over time, you can find trends or patterns in the process.” See http://www.pqsystems.com/qualityadvisor/DataAnalysisTools/run_chart.php (accessed June 3, 2013).

theless, she said, there was not much change in achieving the sixth goal, a 75 percent patient feedback rating of “excellent” regarding physician communication. Although the task force had not been targeting physicians in their efforts, they did want to track progress on this measure for the next phase of the project, she said.

Some of the measures for determining effectiveness included how well the collaborative was working together as a team and how the teams rated their own effectiveness. By synthesizing this information, the collaborative’s leadership helped provide feedback and coach and drive the teams.

The collaborative included long-term care facilities, post-acute care facilities, private practices, and faculty and residency practices—all within the same learning collaborative as acute-care hospitals. At the end of the process, the collaborative’s leadership believed that a third learning session should be added to obtain the greatest benefit. Furthermore, the leadership noted, content expertise in health literacy was needed for the entire collaborative. Teams need strong leadership, organization, data, and management involvement from the beginning, Noonan said.

The participants indicated that they valued the learning environment, wanted more role-playing experience, and desired more help understanding data collection and analysis. At the end of this collaborative process, the teams had been successful and received a great deal of positive feedback. The next question they tackled was how to disseminate or spread these changes throughout the organization.

The task force spent the following 6 to 10 months figuring out how to spread the changes. Different models were explored to disseminate the change package of 28 change items. A key question was whether to spread the entire change package to each facility and run miniature collaboratives on the basis of the 2010 systemwide project, or to send the change package to everyone and allow each facility’s senior leaders to determine the best implementation approach. The decision was to implement a smaller change package, focused on teach-back and Ask Me 3, using video and employee orientation to raise awareness and to spread those changes across the system with one targeted audience.

The task force then needed to ask itself what problem it was trying to solve. Noonan said that the task force believed that one of the most critical factors in improving patient outcomes was to help patients understand and be involved. For this reason, teach-back and Ask Me 3 were confirmed as top priorities for the next phase of spread. This led to the decision to develop the next project—a program called TeachWell. The program was named TeachWell because its implementation coincided with the interactive patient system GetWell, which the hospital had bought and was beginning to implement.

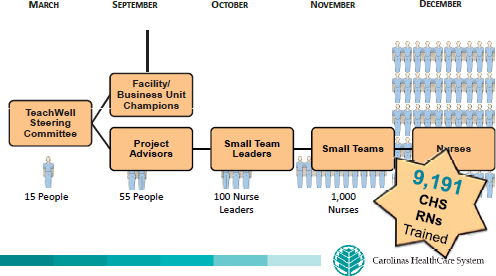

The goal of the TeachWell program was to ensure that all 10,000 Carolinas HealthCare System nurses were trained in and using the two evidence-based health literacy strategies by December 31, 2012. In order to accomplish that goal, implementation would have to be quick, economical, and sustainable, and it would need to be spread across a single unified enterprise.

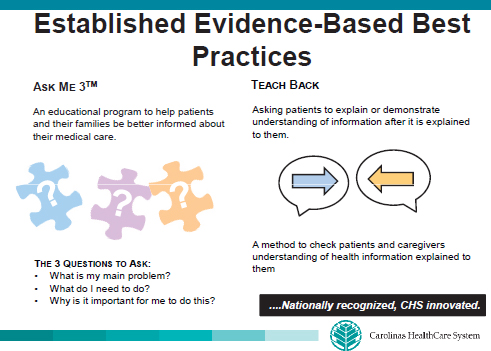

An example of the toolkit Noonan’s team assembled can be found in Figure 2-2; the toolkit features Ask Me 3 and teach-back. Noonan’s team surveyed the staff to determine how often teach-back was currently used. They discovered that the initial collaborative teams had been very successful within their teams, but encountered barriers in disseminating the programs beyond their teams into the facilities. Noonan said they learned that rollout of the programs was not continued at the facilities, which was a significant barrier. Also, there was a lack of observation after training because of time constraints, and there was also a lack of training on how to phrase questions.

Given these findings, the task force knew that there was still a lot of work ahead to improve on the initial gains from the collaborative. In response, they tried a new approach that incorporated design strategy,

FIGURE 2-2 Established evidence-based best practices.

SOURCE: Noonan, 2013a.

improvement science, and a group called a Business Innovation Council. This process brought frontline stakeholders together to design the next steps.

Some of the elements of the toolkit are online, so staff can download content. The toolkit contains quiz cards, tracking metrics, and a storytelling worksheet, among other things. Implementation at the Carolinas HealthCare System began with a TeachWell steering committee, then moved to champions within each business unit and facility and project advisory teams. The program was then rolled out to small team leaders, then small teams, and then to the nurses (see Figure 2-3).

Although the Carolinas HealthCare System did not reach the goal of 10,000 nurses by the end of 2012, it did reach 9,100 nurses, and the project is still operating. The project was led by the Nursing Division. Noonan said that a chief nurse executive who joined the project served as a champion and was able to spread the project to the rest of the chief nurse executives in the system.

Nevertheless, one of the challenges Noonan noted is that although the system has spent a lot of time and money on training, more is now being invested in accountability. Employees must see health literate practices as “the way we do business.” These practices must be recognized as a requirement, not a choice. Monitoring and follow-up are necessary to ensure consistent use. A cultural change needs to take place that starts with raising awareness, teaching, training, and remediation. Ultimately, if

FIGURE 2-3 TeachWell spread.

SOURCE: Noonan, 2013b.

an individual does not participate, there will be consequences, no matter how competent his or her clinical skills. That individual will not be able to work in the Carolinas HealthCare System. This is one of the accountability pieces that are under discussion, said Noonan.

The system incorporated innovative design methodology with change management and improvement science, and, as a result, the package was deliberately left unfinished so that people could adapt it to their own situations. An acute-care facility has different needs from a residency clinic, which has slightly different needs from a long-term care facility or home health services. The project was designed to allow the participants, through testing and data, to make it their own and to involve frontline staff in planning and implementation.

Noonan said that they relied on the Nurse Knowledge Exchange9 concept and a program developed by Kaiser Permanente using the P3D3 Innovative Pathway, a design thinking method for improvement created by members of Carolinas HealthCare System’s internal management company. The package consists of an overview, a playbook, and a toolkit, all of which are customizable. Noonan also noted that reaching out to nurses helped move the project along. There were champions, project advisers, and small team leaders. The goal was to increase awareness first and then to help change and teach the behaviors.

In addressing the third question—“What factors facilitated implementation of the changes to improve health literacy?”—Noonan said that system leadership was a key factor. The project had support from the highest level of leadership, which acknowledged that low health literacy is a problem and decided to do something about it. Another facilitating factor was the use of improvement science methodology and the use of data to drive change, along with shared learning. Finally, the success of the project also rested on the fact that staff did not have to create a change package on their own. They were given a packaged step-by-step process that could be adapted.

In terms of the fourth question, regarding barriers, Carolinas HealthCare System faced time constraints, competing priorities, and limited resources. Noonan said it was estimated that 10,000 nurses participating in a 2-hour workshop would result in a cost of $4 million. Therefore, the objective was to embed the program into the daily workflow so that the nurses did not have to leave work to participate in training. The

_______________

9 Nurse knowledge exchange incorporates “proactive measures and a reliable workflow to support nurses during the essential, and often chaotic, time of shift change.” See http://xnet.kp.org/innovationconsultancy/downloads/NKEplus%20PG.pdf (accessed June 20, 2013).

project was designed in such a way that it could be completed onsite. As a result, the predicted $4 million cost did not materialize.

With regard to the fifth question, that is, how the implementation of changes will be maintained over time, Noonan said that change has been incorporated into employee orientation. The marketing and communication departments are getting involved in the project as well, and it is being incorporated into the GetWell network design and workloads. TeachWell is also being integrated into work standards. The health system is creating a standard that people have to meet after they are trained, and there will be no choice but to follow the program.

The system is moving the program to an operational home, overseen by a chief patient experience officer, so that it will maintain a systemwide focus and not become just another initiative that fades away once attention has shifted. Noonan said that the third stage of the effort will focus on maintaining accountability, training new people, managing the long-term veterans (especially physicians), and spreading the program to staff beyond the nurses.

Noonan noted that the Carolinas HealthCare System has some of the attributes of a health literate organization, including leadership support. The system has identified a chief patient experience officer; it has a chief diversity officer and a patient experience team or health literacy team at the highest levels of the organization. The patient experience and quality and safety leadership teams are now well aligned and working together in this area. Also, the organization is engaged in workforce preparation in its orientation programs. Noonan said that the TeachWell program is mandatory, and use of the skills is observed. Leadership and supervisors are also engaged in coaching and feedback because the data show that this drives behavior change.

Noonan closed her presentation by saying that it is a journey to become a health literate organization, but that the term “journey” sounds slow to her. She asserted that many in the audience are as passionate as she is and that she views the journey with urgency. She believes that progress toward health literacy has to be made quickly and not over the next 20 years.

George Isham, M.D. Chair, Roundtable on Health Literacy Moderator

Cindy Brach, roundtable member, thanked the panelists for their interesting and stimulating presentations. She asked the presenters to

address the issue of measurement. For example, was there any measurement of the extent to which the nurses in the Carolinas Healthcare System who were trained in the use of teach-back actually use teach-back in their practice? How does one measure actual practice, as opposed to seeing that a box was checked? How does one achieve accountability at both the individual practitioner level and the organizational level? What measures are needed for accountability?

Rogers responded that caregivers at Franklin Memorial are used to having people watching what they do. For example, there are frequent audits for hand washing. Measurement is blended with the system. Information is collected by staff members working on the floor who are relieved for an hour or two to conduct the audits. The IT system is also used—with electronic documentation in both the office practices and the hospital, reports are easier to prepare. Now that the assessment questions for office practices and patient education are embedded in the system, it is much easier to generate reports. This is one way in which nurses can be held accountable. Patient experience is also examined using satisfaction questionnaires, readmission rates for particular populations, and emergency room (ER) use for particular populations. The hospital is supporting health literacy and patient education efforts because the staff realize those efforts can affect the bottom line.

McCandless said that it is easy for a provider to check a box, and, using that method, 90 percent of providers in her organization document using teach-back. But there are other ways to measure whether teach-back is being used. For example, patients are asked to “teach back,” that is, to record in their notebooks, that they should bring their medications on their visits. About 65 percent of patients do bring their medicines, which is great for the population served. Teach-back was also found to be effective with telephone interventions, especially for high-risk medications such as Coumadin and its dose adjustment. One of the things the patient is asked to do and to “teach back” is to return a provider’s call to see whether his or her dose needs adjusting. The chart remains out until the patient calls back.

Noonan said that although she is a strong supporter of the use of data in improvement science, measurement does not have to be a big data burden. In her health care system it would take about 18 months to get a report-out of the electronic medical record (EMR) system. Therefore, the organization still conducts chart audits using small, frequent samples. In this manner, over time one can get large sample sizes. Using the correct statistics, one can then find out whether improvements are being made, and the results can be quickly reported to the unit. Data collection needs to be built into the toolkit, Noonan said, and used to drive change and

improvement, but should not be used for judgment or given to some governing body.

A checkmark showing that one has done teach-back is an easy approach, Noonan said. But it is not a guarantee that teach-back has actually been done. That is why observed use is so important. Initially, there was tremendous pushback from the nursing staff when they were told they were going to be observed. But they have ultimately accepted observation of their practice; it is part of what they do, and it is a culture change in the organization.

Will Ross, roundtable member, asked the presenters to describe how, in their organizations, health literacy data collection and analysis relate to their quality improvement departments. McCandless responded that her extremely small organization does not have a quality improvement department. But it does relate to local hospitals, which have been willing to share expertise. Rogers said that the small quality improvement department in her organization has been very helpful in analyzing the data it collects on health literacy efforts. Noonan said that, in her opinion, everyone needs to learn to collect and analyze data, not just those involved in quality improvement.

Laurie Francis, roundtable member, asked the presenters whether they had taught staff about using data in the improvement process. She said she was also curious about whether declines have been achieved in readmissions and ER use.

McCandless responded that it is difficult in a very small clinic to show reduced ER use because the clinic does not have ER data. It does, however, have patient reports. Measurement includes accumulation of new medical debt, which, for the clinic’s patients, may occur in many systems and in many places. This turns out to be the best measure to use, she said, and results show a gradual improvement over time. Questions include whether the patient has seen a provider outside of the clinic and how much medical debt he or she has. Some patients respond that they don’t know, that they cannot count that high. For the patients who do report medical debt, there has been an 82 percent reduction in new medical debt and a 50 percent reduction in hospitalization and ER use. The community hospital is very pleased. It is important to note that this reduction is not due simply to implementing health literacy efforts; it is something the clinic has worked on for a very long time.

Noonan said it is important to measure, simply and easily, the effect of health literacy efforts in a way that can be repeated over time. If readmission rates have decreased, it is difficult to say the extent to which they decreased because of the health literacy strategies or because of care management.

Rogers said her hospital is looking very closely at visits to the ER

because of the cost involved. The mental health brochure, developed with a focus group, has had an impact on reducing visits to the ER. A strategy being explored is whether one of the ER triage options should be referral to a care physician. With funding from a grant, a nurse navigator will follow up with patients to find out their concerns and why they are using the ER as a source of care.

Susan Pisano, roundtable member, said that the presenters had highlighted major barriers related to the marketing and legal departments. She recalled Noonan’s comment that in her system, employment will be at risk if employees are not on board with health literacy. She asked whether that risk would be extended to include the IT, marketing, and legal departments as well as other departments that impact performance but may not be direct caregivers.

Noonan said that marketing and legal departments have to be involved in health literacy efforts. In her system, marketing and legal representatives are now sitting on the systemwide health literacy committee and patient experience committee. They are beginning to ask what they can do differently, whether it is changing fonts or using plain language. Noonan said a significant challenge is finding and hiring health literacy experts who know how to create health literate materials. The question then becomes whether and to what extent to outsource development of materials. If one examines material developed by some of the people who advertise that they use health literate principles, one often finds that the material is still written at the twelfth-grade level, Noonan said.

Rogers said her institution conducts health literacy education with every employee, including the legal and marketing staff and those answering the telephone. Although there is still difficulty, forms and materials are being revised and made easier to understand.

Clarence Pearson, roundtable member, said that the University of North Carolina School of Public Health has a course in patient advocacy, and he wondered whether the speakers’ institutions encourage patients to have an advocate when they get their exams. Noonan responded that, as a pediatrician, she has a parent in the room with the patient most of the time. The hope is that the parent acts as an advocate. Although her system is not yet patient-centered in that way, it does encourage one to bring an advocate and to ask questions.

McCandless said that in her clinic the initial consent-to-treat form asks patients to list the person to whom they would like information to be given and to indicate if they would like to bring that person with them when they make clinic visits. They are also asked to list all contact information for that individual and to indicate whether the clinic can leave messages for and give medical information to that individual. This is all part of the intake process. There are at least 25 patients for whom all

information is filtered through the listed individuals, and those individuals hold the notebooks for those patients, McCandless said.

Rogers said that her institution also asks patients who should be given information and who to talk with on the telephone, and includes those individuals during discharge. Patients receiving mental health care have built-in patient advocates who can be provided by state caseworkers.

Wilma Alvarado-Little, roundtable member, asked how the needs of those with limited English proficiency, the deaf, and the hard-of-hearing community are addressed. “Have your organizations identified these populations within your organizations?” she asked.

Rogers said that there is a large deaf population in the service area and that her organization arranges for an in-person interpreter during visits as well as provides written information. There is not a large population of patients with limited English proficiency, so the organization uses online resources to address their needs. The small population of Somalis usually brings interpreters with them. This is an area that needs further work, Rogers said.

McCandless said that her clinic used to ask whether English was the patient’s first language, but in 5 years no one indicated a language other than English, so that question was dropped. The people who come to the clinic have self-selected a place that serves them well. Those with limited English proficiency select other sources of service.

Noonan said that, like many other organizations, hers is working on improving in this area. When she first started practice at the Carolinas HealthCare System, she was one of the few physicians who spoke Spanish and was frequently called to interpret for others. Over the past 10 years the interpreter service has grown, however, and there are now three fulltime interpreters in certain clinics. The population has changed during this time, from less than 1 percent Spanish-speaking to 67 percent Spanish-speaking. There is also a Nepalese community, and an interpreter has been contracted to assist with these patient visits. But it is more difficult for the private practices. Additional work is needed, Noonan said.

Noonan also said that her system uses Culture Vision, an online tool for health-related cultural information, to raise awareness about different cultures, but, again, this is a work in progress, and even the interpreters could benefit from such learning and become cultural mediators rather than just interpreters. The interpreters also need to learn how to express things properly, Noonan said. When the clinician asks the patient, “What questions do you have?,” the interpreter will often translate that as, “Do you have any questions?” That is not the correct way to pose the question, and training has begun for interpreters.

Cynthia Demarest, a workshop participant from Aetna, said that the presentations were fabulous and that it was exciting to hear about

progress in the field of health literacy. She said she was curious to know what kinds of strategies the speakers used as opening gambits to establish health literacy. For example, did they provide people with the results of an exercise in health literacy or with evidence from research findings? What was the strategic argument to convince leadership? Is there in-house evidence of change? Did the strategy shift as things got under way?

Noonan said her organization used a collaborative style for its first strategy. The opening argument was delivered by content experts— Darren DeWalt and Toni Cordell—as well by patients. The idea was that one needs to speak both to the head with statistics and to the heart with stories. For statistics, the experts described what the literature had to say about why things needed to be done differently. Then, patients spoke about the harm they suffered because of a lack of health literacy, helping show why it is so important. The continuing strategy uses both ethnography and videos to share the voice of the patient and provide the facts.

McCandless said that in her very small organization not a great deal of persuasion was needed. Most came to the conclusion that health literacy was needed because of the things that had gone wrong. Everyone had an example of how health literacy could have improved things. Rogers said they related health literacy to the monetary bottom line. That convinced the administration.

Benard Dreyer, roundtable member, echoed others’ comments about the excellence of the presentations. An issue of concern, he said, is whether what one communicates to the patient is actually actionable, as opposed to informational. McCandless responded that her clinic providers try very hard to be specific. It does not help the patient much to say, “Eat better.” The focus at first is not on what patients will subtract from their diets, but rather on what they can add. For example, the patient might be asked, “Can you buy three fruits and eat them by the time that you are worried that they are going to expire?” Then, gradually, the less-healthy foods are pulled from the diet. The patient writes in his or her notebook what has been agreed to, even if the agreement is to stand up during commercials and jump up and down.

McCandless said her organization involves children when possible, for example, asking, “Will you take your mother for a walk twice a week?” Or the patient might be asked if he or she can take a pet for a walk. For cigarettes the question might be, “By the time I see you next week, you need to be down to 16 cigarettes. Can you do that?” The idea is to set actionable goals that the patient negotiates with the provider.

Rogers said she agreed with McCandless. It is crucial to look at the patient’s goals and see what is important to the patient and what fits into his or her life. The idea is to take one step at a time. What can the patient do to make a difference in his or her lifestyle or health? Rogers said her

organization uses motivational interviewing and incorporates the family as much as possible.

Noonan agreed with Rogers and McCandless and said her system also uses shared motivational interviewing. The patient is asked what is most important to him or her—control, convenience, or cost. In a sense, no matter what the patient’s situation, those are three things that one can work from. So, for example, the goal might be to walk to the mailbox once a day. In the inpatient setting, parents might be asked what single goal they have for their child—should the providers help the child get off oxygen, or should they cuddle him and hold him when he is concerned or crying? That goal is then written on the board in the family-centered rounds. The same thing is done in the neonatal intensive care unit and the pediatric intensive care unit.

The AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit is extremely helpful, Noonan said. The toolkit action plan is simple and straightforward, and although it is designed for primary care, the Carolinas HealthCare System has tested it and found it useful in the pediatric intensive care unit, the inpatient unit, and specialty centers. There is still a great deal to be learned, but when the researchers find something that works, the staff will try to implement it.

Ricardo Wray, a participant from the Saint Louis University College for Public Health and Social Justice, said he was intrigued that both the health system in Maine and the one in North Carolina highlighted the important role nurses play in the implementation of health literacy. He wondered if the presenters could talk about the role of different staff in successfully implementing the attributes of a health literate organization.

Rogers said that nurses have the most direct contact and spend the most time with patients. Nursing is still the most trusted profession, she said, and trust is essential in developing a relationship with patients. Nurses and medical assistants in office practices play a tremendous role in educating patients.

Noonan said that for the inpatient setting, the nursing staff and medical assistants interact with patients at many points. They can provide teach-back throughout the entire hospital stay—from explaining treatment to helping exhausted parents navigate the hospital and find the cafeteria. The nurses now understand that these little pieces, these many interactions throughout the process of care, are opportunities for teach-back.

Andrew Pleasant, roundtable member, asked whether the presenters had suggestions for what would help sustain and expand current efforts in health literacy and if there was something the roundtable could do to support that. Noonan responded that many things could be done but of great importance is the need for health literate education materials that are easily accessible from a centralized location. McCandless said that helping

people know what to look for and modify in their own materials is important. Perhaps a video showing the process of revising some material would be a good learning tool, she suggested. Rogers added that incorporating health literacy and its principles into professional schools’ training curriculums is needed in order to make it part of the culture of each profession.

Ruth Parker, roundtable member, asked whether there was anything in the discussion paper “Ten Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations” that the presenters found particularly useful or any addition that should be made. Noonan responded that it was a very helpful document. She incorporated all 10 attributes (which she designated as high-leverage changes or change concepts) into her improvement science framework. She then broke them down into what they might look like at the actionable, testable level in different settings.

Rogers said the attributes document was a good guide to developing a plan of action. The attributes allowed her to see in greater detail the areas in which she needed to focus her efforts. McCandless agreed that it was a good guide that allowed her clinic staff to see how they were doing in their efforts to become a health literate organization.

Patrick Wayte, roundtable member, asked how the presenters were balancing what the providers thought were the most important things to address versus what patients were most willing to change. Then, he asked, how do you document the choices made? McCandless said that one can find success at every visit regardless of whether that success is just that the patient showed up. One builds on small successes to reach the treatment agenda the provider is concerned about. For example, it is important to engage in physical exercise. Therefore, if a patient is worried about developing Alzheimer’s—tell him or her to go for a walk. If the patient wants his or her diabetes to get better—go for a walk. If a patient is having a hard time controlling his or her depression—go for a walk.

In terms of documentation, McCandless said the goals set are recorded in the notebook and are then tracked by a chronic disease manager. If the goal is to quit smoking, did the patient do that? Did the patient make good food choices? Did the patient meet with the diabetes educator? Is the patient bringing the glucose log with him or her to the visit?

Rogers said that documentation has been incorporated into the care planning process. Noonan said there is still a substantial gap in training physicians, medical students, and nursing staff about the importance of patient-centered care. If one has 7 minutes to see a patient, one tends to focus on one’s own agenda, not the patient’s.

Noonan, L. 2013a. Established evidence-based best practices. PowerPoint presentation, Institute of Medicine Workshop on Organizational Change to Improve Health Literacy, Washington, DC, April 11.

———. 2013b. TeachWell spread. PowerPoint presentation, Institute of Medicine Workshop on Organizational Change to Improve Health Literacy, Washington, DC, April 11.

Rogers, K. 2013. Emergency mental health. PowerPoint presentation, Institute of Medicine Workshop on Organizational Change to Improve Health Literacy, Washington, DC, April 11.