Panel 3: Implementing Attributes of a Health Literate Organization

PALOMA IZQUIERDO-HERNANDEZ, M.S., M.P.H.

President and Chief Executive Officer Urban Health Plan, Inc., New York, New York

The following is a summary of the presentation given by Paloma Izquierdo-Hernandez. It is not a transcript.

Izquierdo-Hernandez said that Urban Health Plan was founded in 1974 by her father, Richard Izquierdo, a local physician who grew up in the neighborhood and believed in the community. The health center was founded on community-based grass-roots principles, and in 1999 the center became a federally qualified health center (FQHC). Currently, Urban Health Plan has a staff of 730 and operates 8 health care practices, 8 school health programs, and 3 part-time programs for at-risk populations. They have had a fully implemented electronic medical record system since 2006, with health education and counseling fully integrated into the templates.

Urban Health Plan serves a predominantly Latino population. Much of the organization’s health literacy efforts are focused around health educators, nutritionists, patient navigators, care coordinators, case managers, and volunteers. Most of Urban Health Plan’s health literacy work occurs in the community and not during the doctor-patient visit. The organization does a great deal of outreach work, including community health fairs and waiting-room presentations. Another type of outreach is

preceptorships, in which medical students come to the facilities to work with patients on health literacy.

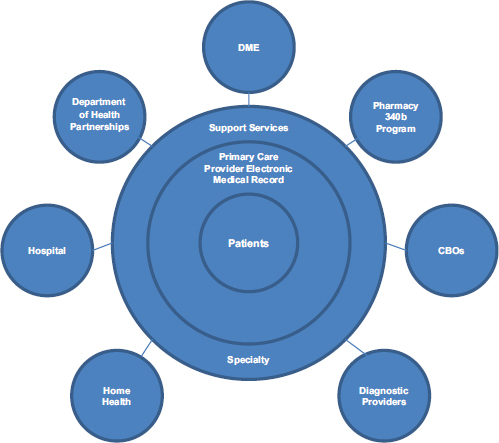

Urban Health Plan uses a patient-centered home model of care (see Figure 4-1). According to Izquierdo-Hernandez, much of its health literacy work is focused around support services provided through the outreach health educators or some other mechanism.

Izquierdo-Hernandez said that she believes that Urban Health Plan has all of the attributes of a health literate organization, although not always in a traditional manner. For example, Urban Health Plan’s leadership has made health literacy a priority from the beginning. The center was also an active participant in the health disparities collaborative that the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) put forth and, through that activity, learned about self-management. Health educators were brought in as a way to address health management through quality

FIGURE 4-1 Patient-centered home model from Urban Health Plan.

SOURCE: Izquierdo-Hernandez, 2013.

improvement efforts. The organization started with 1 health educator and now has 18.

Urban Health Plan has integrated health literacy into performance improvement and trains its workforce to be health literate. There is a staff learning center for professional and personal growth, with classes on how to conduct motivational interviews, how to deal with difficult patients, and how to develop a curriculum for certain chronic illnesses. The learning center was created because, in order to continuously improve health care, the organization has to continuously train its staff. In addition, a director of health literacy was recently hired to coordinate efforts and further integrate health literacy into the organization.

Educational and other materials are standardized to meet the needs of the entire population. Staff also use health literacy strategies and are encouraged to always be aware of how they communicate with patients. The organization hires from the community, which helps build linguistic proficiency into the culture. Easy access to health information and navigation assistance is also provided. One way this is done is through employing greeters to help patients navigate their way through the health centers.

Urban Health Plan’s interest in improving health literacy comes from its history and culture as a community-centered organization. Urban Health Plan’s mission and core values include cultural proficiency, innovation, and performance improvement. Izquierdo-Hernandez noted that working with the HRSA health disparities collaborative brought about an awareness of the need to go beyond the community and also work within the provider setting.

One strategy to move the organization toward a health literate model was to include health educators in performance improvement teams. The organization has also invested in staffing. In addition to health educators, there are patient advocates, nutritionists, care coordinators, and case managers. The entire care team is integrated into the clinical units so that patients do not have to move around the building to see different care providers. These positions have been built into the budget, so they are incorporated into the system, which is important for sustainability. Unless there is a financial catastrophe, the health literacy positions will stay as they have for the past 10 years.

Urban Health Plan also collaborates with some valued partners on health literacy initiatives. For example, a partnership with the Canyon Ranch Life Enhancement Program has allowed Urban Health Plan to take a program from Canyon Ranch and duplicate it in the South Bronx with good results. The program focuses on giving health information to people when and where they need it. One example of success is the significant drop in depression scores for approximately 100 people who have

completed the program. Another important partner is the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, which provides appropriate health information, in forms such as pamphlets and brochures.

The role of stability in an organization is often overlooked in creating and sustaining health literacy efforts, Izquierdo-Hernandez said. A community health center may be especially vulnerable, either financially or operationally. Thus, stability is fundamental because an organization that is in flux or has financial problems will have to use resources for things other than health literacy.

Izquierdo-Hernandez said that it was very important that the board of directors of the center supported health literacy efforts. As an FQHC, the board is at least 51 percent patients. Therefore, it was important for the patients to agree that the organization should be doing this work. The chief medical officer was also supportive of these efforts, which helped ensure provider support as well.

Urban Health Plan has had successful and sustainable performance improvement projects. For example, a program called Shop Healthy Bronx sends nutritionists into supermarkets to conduct food demonstrations. The goal is to increase the use of fresh vegetables and produce and make healthier options available to the community.

There are several barriers or challenges to implementing health literacy in the organization. One of the barriers has been standardization of key messages across the entire network. Finding the right staff, individuals who are linguistically and culturally competent, can also be a challenge, as is finding the right leader. But, Izquierdo-Hernandez noted, the new health literacy director is making progress.

Another major challenge is ensuring continued funding to support this work. Izquierdo-Hernandez said that she thinks health literacy will be supported by payment reform as organizations move from volume to value and start to see some savings that come back to the health centers. Currently, Urban Health Plan is not part of a formal health system but rather is an independent FQHC. It has been able to negotiate some shared savings that help pay for health literacy, and, she believes, as health care reform and payment reform move toward prevention, health literacy work will be more sustainable. In addition, she said, the center will continue to seek outside funding

Izquierdo-Hernandez concluded her presentation by saying that a knowledgeable community becomes a healthier community.

Senior Health Literacy Specialist Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion University of New Mexico Hospitals

The following is a summary of the presentation given by Audrey Riffenburgh. It is not a transcript.

University of New Mexico (UNM) Hospitals is a health system with a 630-bed hospital and 24 offsite health clinics with about 500,000 ambulatory visits per year. UNM Hospitals is the only medical academic center in New Mexico and the region’s only Level 1 trauma center. The system has about 6,000 employees, and about half of the population it serves lives in poverty. About half of the region’s population self-identifies as Hispanic or Latino, about one-quarter as white or Anglo, and about 10 percent as Native American (from a variety of different tribes). Other, smaller populations make up the other 15 percent.

Health literacy is relatively new in the organization, and it is currently placed in an office that is also relatively new, Riffenburgh said. In 2010, the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion was created for the purpose of ensuring that all patients received the safest, most effective, and most sensitive care regardless of their race and ethnic identification or their health knowledge or literacy. Riffenburgh’s position was created in 2012 to help achieve those goals.

UNM Hospitals is working most intensively on the sixth and eighth attributes of a health literate organization: interpersonal communications and printed materials. One of the system’s greatest successes in interpersonal communication has been a strong and vibrant interpreter language service program. There are 20 onsite interpreters—16 Spanish, 3 Vietnamese, and 1 Navajo. The program also serves about 23 other language groups through video and telephone interpreting. This is a vibrant community of dedicated people, Riffenburgh noted.

Another component of efforts to improve interpersonal communication is raising awareness across the organization of the different ways that providers and patients use language and the importance of plain or “living room” language. To further that awareness, Riffenburgh said, she has made a plain-language thesaurus available. It is based on a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention document, to which she added the thesaurus she had been developing for 20 years as part of her workshops. The thesaurus is publicly available on the Internet. The organization is also just beginning a teach-back initiative.

The system is also focusing on making printed materials easier to understand. This means not just making them available in different lan-

guages, but also writing them in a way that allows for better understanding. The system has provided resources to hire professional plain-language editors and a graphic designer who has special training and expertise in readability. Riffenburgh said that although she is also working to build systemwide change, she also has been given the task of editing patient documents, and this has taken a great deal of time because there are so many.

One of the projects under way with the graphic designer is to create a new style for all of the organization’s documents—a new look for standardization and branding. This will culminate in a template of the new style and a “gallery” of sample materials available on the system’s Intranet so that people in the organization can see what plain language looks like. Riffenburgh said that she found that providers and hospital staff have often misunderstood what plain language is, and that has proven to be a barrier.

She is also designing a more formalized system for document approval to be implemented in the future. Currently, submitting documents for review of readability and usability is voluntary, but the goal is to make it mandatory, at least for all new documents. Riffenburgh said she is training a team of people to be document reviewers. She has also created some tip sheets to help people as they review, write, and format their own documents.

Printed materials are all supposed to be translated into Spanish and Vietnamese, according to Riffenburgh. That effort is in progress. Ensuring that the English versions are more focused and actionable will help, because when something is written at a difficult level in English, it will not get better when it is translated.

Turning to the first and second attributes, leadership and measurement, Riffenburgh said that she believes these are strengths of the UNM program. Key leaders at the organization are supportive of the effort, although some still need to be convinced, she said. She has received support for editing documents even when providers have resisted, and resources have been provided for this and other work. Early in the effort, an organizational self-assessment was conducted, which provided some very good data about what needed to be done.

Preparing the workforce is a major area the organization is addressing, Riffenburgh said. She, on the hospital side, and a key physician who works on the medical school side give presentations to people within their respective spheres of influence to raise awareness.

Riffenburgh also teaches a 2-day intensive workshop that she taught for years around the country when she was a consultant. Seventy people were trained in the first year, which she believes is a good start. There is also an online competency unit on health literacy that all employees must complete.

The health sciences center library has put up an entire website on health literacy. Riffenburgh gave the library an extensive bibliography, and it includes links to a wide variety of information, making it a clearinghouse. It is available publicly and contains direct links to a number of health literacy information resources.

UNM Hospitals is working hard to improve the overall environment as far as ease of navigation and accessibility are concerned. Improving signage is a challenge, but the effort is under way. Riffenburgh serves on the way-finding committee, but it is difficult to implement health literacy measures because many decisions have already been made.

The patient financial services department does an excellent job helping patients navigate and get the help they need, Riffenburgh said. There is also a special Office of Native American Health Services, which does an outstanding job helping Native American patients navigate the system. In addition, there is a new patient portal, but unfortunately most of the information on it is not very readable for many of the patients the hospital serves. Riffenburgh has edited some of the text so that it is at an eighth-grade level, but other text has been declared off-limits to editing.

To address health literacy in high-risk situations, Riffenburgh said she is working with a palliative care doctor to revise the advanced directive forms. She is also working to make consent forms and medical intake forms easier to understand. A team of doctors inside the system created a simpler consent form, which has been approved; however, some physicians choose not to use the form.

According to Riffenburgh, the interest in health literacy at UNM Hospitals was generated by key leaders who became aware of the communication problems. At the same time, the national forces for change—the reports, the standards, and The Joint Commission—were gaining momentum. This prompted some of these leaders to begin speaking to colleagues to encourage change. Probably the most significant factor, however, was a lawsuit filed in 2005 demanding language access because the hospital was not doing enough to provide services for speakers of languages other than English.

Strategies that have moved health literacy efforts forward at UNM Hospitals include gaining the support of key leaders and champions and linking health literacy to safety, quality, patient satisfaction, and cost savings. By consistently making these links, health literacy champions in the organization are able to keep this work a priority. These leaders continue to challenge people across the organization at all levels, saying, “We can do better than this.” They have provided commitment, tenacity, and focus. The lawsuit facilitated the change, but leadership has kept it going.

Implementation of national health reform is expected to bring new patients in to the system. UNM Hospitals is the system that best serves

low-income patients in the area. This fact, coupled with new Medicare readmission policies, has provided incentives for the system to continue to make progress in health literacy.

One barrier to implementing health literacy has been resistance to using plain language. Many people do not believe or do not understand that there is really a mismatch between what the system demands and what patients can navigate. Riffenburgh related an anecdote that at a meeting with a provider, she showed a video of speaker and health literacy activist Toni Cordell talking about her own experiences as a low-literacy patient. When the video was over, the provider said that he did not believe it could be true. He had trouble believing there could be such a gap in understanding between doctor and patient.

Competing priorities have also proved to be a barrier. In the past year, there have been system evaluations by the Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission. Those visits generated a huge amount of work. In addition, the organization was implementing some changes to its electronic health record and combining four disparate parts of the UNM Hospitals system into a single health system. The people who worked in the system already had a lot of work to do. It is a challenge to get people to take the extra time to attend classes and focus on health literacy, Riffenburgh said.

At the same time, some people are beginning to see and understand the need for health literacy efforts, and they have a great deal of enthusiasm. This brings its own challenges, Riffenburgh noted, as the volume of work has outpaced her single position. There is concern that this lack of resources will lead to waning enthusiasm if people think they are not getting responses or results.

Another challenge is resistance to change in general. As an example, Riffenburgh said that she had created a consent form that was in use for a while. The Joint Commission evaluators called it a best practice, but the providers said they were not comfortable with it. It used the word “die” instead of “mortality,” and some patients were reacting to that. So, now, the old form, written at college level, is back in use.

Riffenburgh concluded her presentation by saying that it will be a challenge to continue and to maintain the changes but that support from leadership remains strong, and she will continue to promote health literacy at UNM Hospitals.

Consultant, Health Education Eli Lilly USA, LLC

The following is a summary of the presentation given by Lori Hall. It is not a transcript.

Eli Lilly is a global pharmaceutical company headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. It has offices in Puerto Rico and 17 other countries, with a portfolio of products sold in approximately 125 countries. The company was founded in 1876 by Colonel Eli Lilly, a pharmaceutical chemist and a veteran of the U.S. Civil War. Many know Lilly from its diabetes portfolio; it was the first to bring commercial insulin to the market. The company still has a very strong presence in diabetes care, which remains central to the company’s mission. Overall, Hall said, Lilly’s mission is to provide answers through medicines and information for some of the world’s most urgent medical needs.

Hall said Lilly’s journey toward becoming a health literate organization began on the front lines, that is, in the health education department, rather than in the executive office. The health education department has a vision to provide foundational knowledge and skills to engage, educate, and empower patients to be active in the management of their own health care. Its mission is to create and deliver nonbranded, nonpromotional patient education materials aligned with health literacy principles in the areas where Lilly has presence and expertise. Hall stressed that the area of the company in which she works has nothing to do with products but rather is focused on patients and education. In fact, she said, there is a firewall between what her group does and what the marketing teams do.

The health education department is a customer-facing team of health care professionals focused on delivering positive experiences for patients. In addition to the consultants who work in the Indianapolis office, there is a field team of 10 health education professionals who have advanced-practice nursing and pharmaceutical experience. They interact with national health plans, which include UnitedHealth, Humana, and Aetna as well as many smaller regional plans. The consultants do not talk about Lilly’s medicines, but about patient resources. They try to understand unmet patient-related needs and to match those needs with the portfolio of patient education resources available at Lilly.

Health literacy is a new initiative for Lilly. The effort is still in its infancy at the company, with a small group of people actively engaged in it. Lilly is conducting health literacy pilots in the areas of clinical trial management and informed consent, the medical call center, medical education grants, and brand marketing. These activities align with the

health education department’s overall vision of engaging, educating, and empowering patients to be more active in their health care.

Hall said that in addition to internal activities, Lilly also engages in health literacy activities in the broader community, for example, making health literacy presentations during employee wellness series. Lilly also sponsors events called Lilly Neighbor Nights, because although it is a large corporation, it is also a neighbor to a large residential community. Once a year, Lilly invites the community to come and see what they do. One of the most recent events was focused on health literacy. Lilly has also partnered with Indy Reads, an adult literacy program, and has made presentations at the Marion County Public Health Department.

Lilly is supporting educational grants to a number of regional medical education programs, Hall said (see Table 4-1). The intent is to educate primary care physicians in the area of health literacy, and attendance was very good at the Pri-Med South and Pri-Med Houston conferences. Various other events are planned for the rest of 2013.

On a national level, Lilly recently won the Institute for Healthcare Advancement’s Health Literacy Award in the published materials category. Hall said that she and her colleagues are very proud of that honor, but, more important, it helped to legitimize Lilly’s corporate health literacy initiative—so that it is not seen as just the passion of certain individuals. Experiences such as winning an award help health literacy gain support in the organization.

TABLE 4-1 Regional Medical Education Programs (Supported by Educational Grants from Eli Lilly and Company)

|

|

|

| Region | Program |

|

|

|

| Pri-Med South and Pri-Med Houston | Improving Health Literacy and Patient Provider Communication: A Call to Action for Healthcare Providers |

| Primary Care Network | Health Literacy and Patient Safety: A Primary (Care) Concern |

| CME INCITE/Virtual Rounds™ | Addressing the Health Literacy Epidemic: Prescribing Toward Better Patient Outcomes |

| Pri-Med West | Health Literacy—The Whole Patient in Primary Care |

| Integritas Communications/Web-based | Improving Health Literacy in Primary Care: Identifying Deficiencies and Promoting Shared Decision Making |

| Illinois Academy of Family Physicians/Ed Track | Keep It Clear: Developing Communication Skills to Work with Patients with Limited Health Literacy |

| Boston Medical Center | Annual Health Literacy Research Conference (HARC) |

|

|

|

SOURCE: Hall, 2013.

With regard to the 10 attributes of a health literate organization, Hall said that Lilly has accomplished the eighth—designing, developing, and implementing patient education resources that meet health literacy principles. She said they are working to master the other attributes, but are still early in the process.

At Lilly, interest in health literacy began in 2009 with the efforts of a small group in consumer marketing. They commissioned the Health Research for Action center at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health to conduct an assessment of how health literacy and clear communication issues were addressed at Lilly. It was a very small assessment, consisting of interviews with 20 key staff at Lilly and selected agencies that work with Lilly.

The key findings were both interesting and a cause for concern. The interesting parts were that most of the key informants believed that health literacy is important, that it is something Lilly should be involved in, and that it is something that could be better understood by those in the organization. The interviewees thought that understanding health literacy would help Lilly better comply with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations and guidance.

But the assessment also identified challenges, according to Hall. First, the interviewees said that Lilly simply did not have adequate knowledge and expertise in health literacy. Because Lilly outsources the creation of its materials, the limited pool of affordable contractors who have health literacy expertise was a challenge. Identifying agencies that have the necessary expertise was a further challenge.

The assessment also identified a lack of sufficient standards and protocols, which led to inconsistency in materials. Constraints on staff time were also an issue, as is the case in many organizations. Lack of trust and communication among departments was an additional barrier at Lilly. Hall said that at times FDA regulatory requirements and health literacy best practices are in conflict. And, finally, Hall noted, there is always some resistance to change.

Hall said that when she heard a presentation on the findings of the assessment, it inspired her to take up health literacy work at Lilly. She realized that to be effective, any efforts to create a health literate organization had to support Lilly’s business plan and build on efforts that were already under way, so that health literacy is not a separate workstream, but instead is integrated into the work that everyone is already doing. Efforts also need to be anchored in quality, safety, and patient-centered care.

To create the necessary momentum for health literacy efforts to succeed at Lilly, the organization needed evidence-based tools and resources and a multidisciplinary approach. Support from senior leadership was

also needed, and, most important, awareness of the need for health literacy efforts.

Hall created a team of advocates from many of the major consumer and patient touch-points within the organization. This team calls itself Health Literacy Matters. It consists of representatives from consumer marketing, clinical project management, the medical call center, labeling, and global patient safety, among others. The team focuses on raising corporate awareness of how better health communications help improve patient adherence and, therefore, help achieve better outcomes. Although none of the members of the team has advanced credentials in health literacy, it is a frontline group of people who care passionately about patients.

The team organized activities around Health Literacy Month in October. They began with making presentations throughout the organization that were designed to raise awareness. They also created an internal online collaboration site with facts, tips, tools, and resources. The team developed a multimedia internal communication plan that included putting Health Literacy Matters on television screens throughout the organization and in the internal newsletter. Efforts culminated in October when, once each week, a different national thought leader in health literacy came to speak at Lilly. This gave the effort some momentum and generated more interest within the organization.

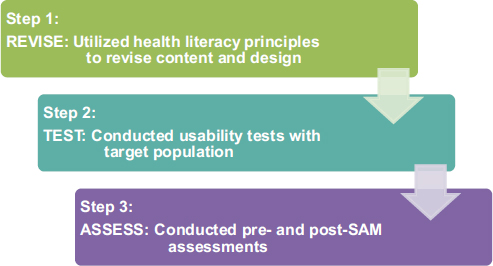

Other efforts have begun as well, Hall said. A small health literacy pilot project involved developing patient education materials that are not branded or disease-state specific. The existing materials were tested and rewritten to follow health literacy principles. Usability tests were conducted with patients and consumers, and pre– and post–Suitability Assessment of Materials1 (SAM) tests were conducted. But the real test, Hall said, is the reaction of the health plans.

Customer requirements are practical requirements; for example, material must fit into a number-10 envelope. However, when Lilly could demonstrate the effectiveness of the revised materials, they were allowed to bend the requirements. Now, the revised brochures titled “Feel Your Best” are among Lilly’s most widely used patient brochures. As a result of this success, the approach taken by the health education department (see Figure 4-2) is now serving as a role model pilot program for the rest of the organization. For example, Hall said, there is a pilot that will take a more holistic approach to training key stakeholders, including legal, medical

_______________

1 The SAM instrument “offers a systematic method to objectively assess the suitability of health information materials for a particular audience in a short time.” It was developed in 1993 by Leonard and Cecilia Doak and Jane Root. See http://aspiruslibrary.org/literacy/SAM.pdf (accessed June 20, 2013).

FIGURE 4-2 Three-step approach.

NOTE: SAM = Suitability Assessment of Materials.

SOURCE: Hall, 2013.

and regulatory, and marketing. The goal is engage these stakeholders, who will then become role models for others in the organization.

Hall concluded her presentation by saying that her team will continue to share its successes and will not be discouraged by setbacks. Lilly has a number of health literacy champions within the organization that make her team’s efforts possible. Hall said that she intends to keep the conversation about health literacy alive at Lilly and to keep moving forward in making Lilly a health literate organization.

Health Management Consultant Iowa Health System

The following is a summary of the presentation given by Mary Ann Abrams. It is not a transcript.

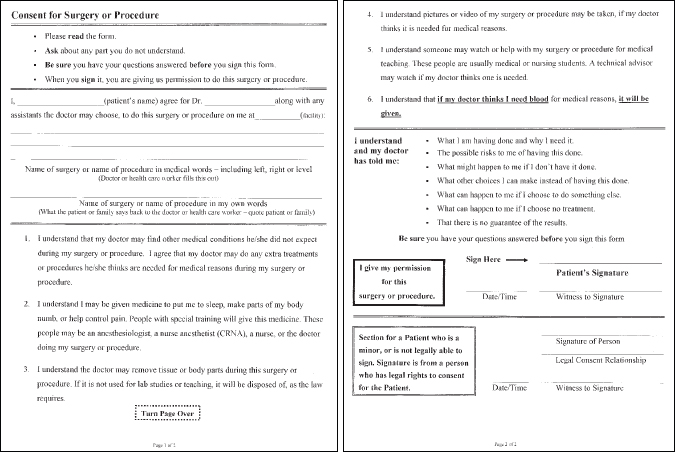

The Iowa Health System has been engaged in health literacy efforts for almost 10 years. Abrams focused her presentation on a reader-friendly consent for surgeries and procedures and described its development in the context of the attributes of a health literate organization.

Although health literacy work at the Iowa Health System originates in the Department of Clinical Performance Improvement, development of the new consent materials was a crosscutting, systemwide quality initia-

tive that incorporated health literacy. The immediate goal was to develop standardized, reader-friendly consent forms in both English and Spanish, to use throughout the informed consent process and within the framework of plain language, teach-back, and other health literacy principles.

Still, this project was not just about revising forms. The wider organizational goal was to use the project as a strategy to

- educate staff and providers about health literacy concepts;

- promote patient understanding through plain language and teach-back;

- optimize perioperative consent communication; and

- encourage adult learners, risk managers, health care providers, and the law department to work collaboratively with the health literacy team.

The product of this effort, that is, the consent form, was to be made available for use throughout the Iowa Health System’s affiliated hospitals, clinical sites, and physician offices, consistent with their individual policies and applicable state and federal laws.

The original consent form was written at the college level and was not very visually inviting. The revised consent form has a reader-friendly format and wording along with space for teach-back, where the patient describes procedures in his or her own words. Box 4-1 shows how complicated phrasing was modified using plain language.

BOX 4-1 Consent Form Text—Old and New

Old Text

“I authorize ______ Hospital to retain, preserve and use for scientific, teaching or commercial purposes, or to dispose of at their discretion, any specimens or tissues removed from my body. I release to _____ Hospital all of my ownership interests or other rights to these specimens, tissues or other materials.”

New Text

“I understand that the doctor may remove tissue and body parts during this surgery or procedure. If it is not used for lab studies or teaching, it will be disposed of as the law requires.”

SOURCE: Abrams, 2013.

The revised consent form (see Figure 4-3) is a one-page, two-sided document, with a readability level of seventh to eighth grade. It has good spacing, careful use of bullets and numbering, selected use of bold text, and directions, said Abrams. It incorporates the key elements of informed consent and includes plain-language descriptions of other pieces of the consent process, such as the taking of photographs, what happens to tissue, and a final reminder to ask questions before signing the form. The revised form is part of an overall health literacy–based consent process that includes surgeon-patient discussions conducted in plain language.

The health literacy team began revising the old consent form with input from a number of individuals, including the New Readers of Iowa, a group of adult learners. Multiple revisions were made until the form was deemed functional. Key leaders, both formal and informal, were involved from the start and helped guide the early pilot work. A small pilot test was conducted at one hospital with one surgeon, and revisions were made as necessary. Abrams said it was important that the hospital and the team working on the pilot documented all the steps of the development process so that it could be replicated at other sites. That process evolved into one that included informational meetings, written communication, and further training before an individual hospital would begin to use the new consent process.

The pilot test included evaluating whether the success of the new form differed by patient demographics and whether the amount of time taken to complete the process increased because patients were actually reading it, Abrams said. And, if so, she added, was that a problem? They were also interested in general feedback. Did the staff like it? Did the patients?

Evaluation results showed a marked increase in the number of patients and family members who actually read the consent form (from 25 to 90 percent), an increase in the proportion of patients who were able to describe their surgery in their own words, and increased patient comfort with asking questions. There had been some concern that providers might not like the new form and might find the new process disruptive, but this turned out not to be the case. Patients, families, and nurses were very pleased with the new procedure, noted Abrams.

The initial work was completed about 8 years ago. Each affiliate hospital is continuing to implement the program, adapting the process as necessary. There is an implementation checklist for individual organizations that identifies important stakeholders who must be involved before changes are made. The training focuses not just on health literacy and teach-back, but also on the consent form as a tool to verify patient understanding.

Even with years of experience in implementing the health literate

consent process, individual hospitals are encouraged to do small tests of change to see what might not work well in their settings and to allow some time to allay concerns or fears. It is important to make sure that the process is adapted to each hospital, because even though the organization is a system, each affiliate has a great deal of independence.

The Iowa Health System has achieved 9 of the 10 attributes of a health literate system, Abrams said. Interest in the consent project within the context of the health literacy effort was generated when people noticed that the original form was very hard to read. For example, the director of risk management, who is a member of the law department and serves on the health literacy collaborative, identified case law concerning communication of risk in which claims were filed due to lack of informed consent. Lack of understanding of informed consent is also a patient safety issue.

The evaluation of the form led to the questions, If the form is too difficult to understand, is a patient’s signature meaningful? Are patients undergoing surgery without fully understanding the procedures, their risks, their benefits, and the alternatives? Could a simpler, more effective tool be developed?

The law department was very supportive of this initiative, Abrams said, on the basis that the doctrine of informed consent holds that patients have the right to participate in decisions about their own care. The national focus on health literacy also helped lend credibility to this initiative, as did the growing number of standards and best practices in the field, for example, the National Quality Forum’s Safe Practices for Better Health Care, which calls for use of teach-back and for improving the quality of consent documents.

In addition to having the support of the health system leaders and the law department, the health literacy team held a 2-day workshop to build health literacy team skills, knowledge, and understanding of plain language. The goal of the workshop was to help people recognize plain language and understand its importance. The involvement of the adult learners was also critical to the success of the project. Their involvement helped overcome concerns about readability.

Work in this area is ongoing, Abrams said. The health literacy team at each hospital affiliate identifies key participants to include in implementing the new process. The health literacy teams build tools, prepare educational materials, conduct training, and contribute to a library of readable consents on the internal website. They have also been able to expand health literacy efforts to other procedures.

Existing health literacy teams that could test and implement the new process were a major facilitating factor, according to Abrams. Also, because the process was not viewed as external to regular responsiblities,

the support of people with appropriate knowledge and expertise was forthcoming.

Steps in the development process were as follows: (1) articulate health literacy as a system goal; (2) engage in multiple rounds of feedback and input from consumers, particularly those with low health literacy; (3) underscore the value of teach-back; (4) monitor and report back on impact; and (5) relate the initiative to quality, safety, patient-centered care, risk management, and the transformation of the health care system.

Barriers included inertia as well as competing priorities that take time and resources, Abrams said. Although she found that resistance to change and legal issues were minimal barriers, there were some “turf” issues over the branding on the forms. And, finally, the affiliates are independent and cannot be forced to use the new form. There were some early adopters, and there are some who are just beginning the process of implementation.

Maintaining changes over time will, Abrams said, be facilitated by a documented, structured approach that can be replicated. This approach also helps the changes spread to additional hospitals and allows expansion to other areas, such as radiology, consent for treatment, and consent for blood transfusion. The effort is sustainable because it has become part of routine operations and because it benefits hospital operations. For example, one of the hospitals had more than 100 condition-specific forms. For them this was an efficiency issue; they were able to retire hundreds of forms and replace them with a generic one.

Abrams said many key factors led to the program’s success. First, leadership was very important, especially from the law department. A second key factor was integrating health literacy into planning, quality, and patient safety, and coupling that effort with evidence and resources from national organizations in support of health literacy. Another factor was having expert training to help jump-start the effort, as well as ongoing training and resources to prepare the workforce. Abrams said that she thinks the increase in the number of patients reading the form showed that the consent process is a navigational issue. The revised process and form improve patients’ ability to navigate that aspect of care.

In high-risk situations, the new form helps address doubts that the patient is giving true informed consent. Abrams ended her presentation by thanking the people who have led and facilitated health literacy work at her organization.

George Isham, M.D. Chair, Roundtable on Health Literacy Moderator

Isham said that the presentations reminded him that the passion and commitment to do public good began, for many organizations, with being responsive to patients and patient care in the community. He said he thinks it is very important that people’s work is aligned with a purpose and a true commitment to helping others.

Robert Logan, representing roundtable member Betsy Humphreys, noted that the National Library of Medicine (NLM) was founded on the singular efforts of one person 160 years ago, John Shaw Billing, and that it is amazing what one committed person can do. The NLM has a special interest in Native American health. The library has an exhibition, a website, and an iPad application called NLM Native Voices dedicated to those issues and the many perspectives on health among Native Americans, including Alaska natives and native Hawaiians. Logan asked Riffenburgh if her organization had any special health literacy strategies or initiatives for the Native Americans.

Riffenburgh said that it is a challenging area. UNM Hospitals has had a Native American Health Services unit for some time. The hospital is located on Indian land, which is leased by the hospital for $1 per year. The hospital has made a special commitment to people of Native American heritage. Native Americans have specific patient navigators and advocates to help them in the system. The health literacy efforts that Riffenburgh has initiated are not focused on that population specifically, however, because every population the hospital serves has the same level of need. Riffenburgh said that much of the assistance provided to Native Americans is related to health literacy, but there is no formal connection. She said that she and the director of Native American Health Services are in the same organizational unit, but their work does not yet overlap.

Darren DeWalt, roundtable member, observed that most of the efforts presented involve intensive organizational change. Health literacy is not something that can be picked up and simply dropped into place. Many people and organizations say they can and do develop health literate products that can be applied anywhere, but the presenters suggested that it is difficult and time consuming to implement organizational change to improve health literacy. DeWalt then asked Izquierdo-Hernandez to describe what she meant when she talked about standardizing key messages and how she does it.

Izquierdo-Hernandez said that her organization’s health educators have key messages that are developed jointly with patients and the director of health literacy. They are focused around specific health conditions and consist of a series of topics to be covered by the health educators. There is standardization among the topics and messages, and everyone across the organization is aware of those key messages. Although a lot of health literacy material is being created by individual organizations for the communities they serve, that material can be shared with other organizations and communities and adapted as needed. Dissemination can be a challenge, she said.

DeWalt then asked what in health literacy can be borrowed or adapted from other organizations and what needs to be developed within each organization.

Riffenburgh said that a number of resources, such as the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit and the TeachBackTraining.org website, can be helpful to any organization undertaking health literacy initiatives. But, she said, there is another category of tools that need to be developed within an organization because they have to be context-specific for the politics and structure of the specific organization.

Hall said that at Lilly she has used many tools developed outside the organization, particularly ones that have been evaluated for effectiveness because, as a pharmaceutical company, her organization is very data-driven. But she also adapted tools so that they were appropriate for Lilly, even changing materials for use in different parts of the organization. It is important to use the language of one’s audience and to understand specific motivations and incentives to engage in health literacy, Hall said.

Abrams agreed that there are great tools available that can be adapted for particular situations. Each tool needs be evaluated for its usefulness and effectiveness in the specific context in which it will be used. One cannot simply download a form that claims to be written in plain language and call that health literacy. Abrams said she has seen a lot of progress in the past 5 or 10 years with organizations taking a more thoughtful approach to the development and use of materials. There are also changes taking place within the culture of medicine and health care that encourage linking quality and performance improvement efforts with health literacy. These linkages and integration should become part of the way a health literate organization does business, Abrams said. She emphasized that a very important thing to remember when developing health literacy initiatives within an organization is the voice of the patient. Engaging with patients and adult learners in a respectful, mutual partnership is very important to developing programs.

Margaret Loveland, roundtable member, said that her organization, Merck, has developed a training program for everyone involved in creat-

ing consumer materials, including outside contractors and vendors, to ensure that their materials meet the same standard. She said a great deal of effort was required to achieve minimal participation in health literacy activities until a new global marketing leader who was passionate about medication adherence started working at the company. This focus on adherence led to a focus on health literacy, and that was the beginning of leadership support. Loveland said that initially the Merck department of health literacy had only one employee, but it is a much more active entity now. She said that although Merck is more active in health literacy, it still is not part of the culture, and there are issues with both the legal and marketing departments. She asked if Hall faced any of the same issues in her work.

Hall said she had faced some of those same issues. She said that her background included work in marketing, sales training, and leadership development, which gave her a better understanding of their perspective. Although a great deal of work remains to be done, she said, she is working with the marketing department to help them understand that engaging in health literacy could give the organization a competitive advantage. As a result, they have begun assessments of a few of the marketing materials to see how they can be improved from a health literacy standpoint.

Isham said the roundtable had engaged in work related to clarity of communication about drug dosing and other issues and has presented workshops on the topic in the past. He noted that several speakers mentioned regulatory and legal issues related to pharmaceutical patient education materials and said this might be a topic the roundtable should take up again. Addressing the challenge of communicating clearly with regard to medication and drug dosing in the context of the regulatory environment is an important issue, he said.

Wilma Alvarado-Little, roundtable member, asked Abrams and Riffenburgh about translation of consent forms into languages other than English. What kind of guidance did the translators receive regarding health literacy and plain language? she asked. Are health literacy and plain language considered when dealing with outside vendors?

Abrams said that Iowa Health Systems has a team of translators within the system, and the health literacy team works with them. She said it is very important to translate from plain-language English to plain language in the new language, because the original document needs to be a health literate document. She said they also commission two translations for each document to be sure that they are getting the best product. They also perform a small test with the translated document to further validate that it is well written.

Riffenburgh said the issue of plain-language translation is something she is still working on, particularly building a relationship with inter-

preters. She is working to help them understand what they can do to make information more readable even if the document in English is very difficult to read. One of the challenges is the perception that translators are legally or ethically bound to produce the same document in the new language—that everyone should be given the same unreadable document. The translators are also concerned that if they change a document, then they will get in trouble for it. The translators and interpreters have not had any training with the consent forms, and it is a conundrum, Riffenburgh said, because they are stuck with the materials they are given. Riffenburgh said that in response to this issue, she has focused on improving the English- language documents so that the translators and interpreters have better material to work with.

Hall said that once they have created patient education materials in English that follow health literate principles, they translate them into other languages, and then a separate group translates the material back into English. This is one way to check that the health literacy principles are maintained in the documents, she said.

Susan Pisano, roundtable member, said she was glad to hear presentations from such a geographically diverse group because it meant good work was being done across the country. She said that a common complaint of members of her organization, American’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), is that even when an organization is doing well with health literacy internally, when they need to contract work externally they run into a problem. She wondered if contracting with other health literate organizations could be considered an aspect of being a health literate organization.

Riffenburgh said she is a specialist in materials development with a background in adult literacy and special education. A short time ago she conducted a research study to find out whether an online search for easy-to-read health materials identified materials that met any kind of health literate guidelines. The answer is no, they did not. Many organizations and individuals claim they are creating materials that are easy to read, and the materials are posted in a variety of places, but they are not health literate materials. The difficulty is finding vendors who do use health literacy principles. She said she used to be able to go to the adult literacy community to conduct field tests of materials. But, now, many of those communities in her state say she cannot conduct tests to receive feedback because of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

Abrams said that when requests for proposals are issued to develop educational materials, the application guidelines should specify that the materials adhere to a checklist for reader-friendly print materials.

Pisano said AHIP has developed such a tool to assist health plans. Izquierdo-Hernandez asked if there is a dialogue about health literacy

in the health plans. Pisano said yes. She staffs a health literacy task force that has representatives from 65 of AHIP’s member companies. There are monthly programs on health literacy, and they develop tools and resources for companies to start and advance health literacy programs.

Rima Rudd, roundtable member, said that when we look at organizational change, we focus on process. Everett Rogers, an expert in the diffusion of innovations, said that organizations do not adopt an innovation, they adapt it. The articulation of the change, the modifications, and the adaptations are incredibly informative. They build knowledge, and that is how we can move on, she said. So, instead of trying to package and distribute a health literate consent form, one should package the process so that others can understand how to develop the form.

Brach said she coauthored a paper several years ago that had nothing to do with health literacy called “Will It Work Here?” The paper is about looking at innovations to determine whether they can be adapted to one’s organization. Brach then recalled Izquierdo-Hernandez’s comment about negotiating shared savings and asked her to talk about what kinds of shared savings were negotiated, with whom they were negotiated, and what was included in the calculation of costs.

Izquierdo-Hernandez said they negotiated shared savings with a health plan. Her organization was clearly the lowest-cost provider in the plan network. If the center does well, it shares in the savings, but if it does not do well, it shares in the risk. For the past 18 months, the center had done well, and the shared savings enabled the organization to reinvest in its system to expand health education and care coordination.

Isham concluded the discussion session by thanking the panel.

Abrams, M. A. 2013. Consent for surgery or procedure form. PowerPoint presentation, Institute of Medicine Workshop on Organizational Change to Improve Health Literacy, Washington, DC, April 11.

Hall, L. 2013. Three-step approach. PowerPoint presentation, Institute of Medicine Workshop on Organizational Change to Improve Health Literacy, Washington, DC, April 11.

Izquierdo-Hernandez, P. 2013. Patient-centered home model from Urban Health Plan. PowerPoint presentation, Institute of Medicine Workshop on Organizational Change to Improve Health Literacy, Washington, DC, April 11.