Science and engineering talent can be found among young people in every state,1 and the long-term health of the U.S. research enterprise depends on providing opportunities for these young people to develop their talents no matter where they may live or attend college. Participation in research is an essential component in science and engineering education.

Consequently, students in all parts of the country must have the chance to participate in high-quality research, and it is in the national interest that federal funding be provided to universities in every state to ensure that these research opportunities are available. The committee asserts that the nation needs a robust supply of researchers to keep expanding the frontiers of knowledge, and all states need citizens capable of understanding and applying new developments in science and engineering to their work, whether in industry, health care, education, environmental protection, or other fields of endeavor critical to the nation’s well-being.

The primary federal programs designed to ensure that all states are capable of participating in the nation’s research enterprise fall under the general rubric of the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR). The National Science Foundation (NSF), Department of Energy (DOE), Department of Agriculture (USDA), and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have active EPSCoR programs. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) have a related program called Institutional Development Awards (IDeA).

In addition to pursuing the original mission of enabling universities in every state to be able to compete for federal research funding, EPSCoR programs have over the years added other goals, such as enhancing innovation to stimulate economic development and entrepreneurship and expanding the diversity of the science and engineering workforce. The broadening of the EPSCoR mission has increased the difficulty of assessing the program’s effectiveness.

Sizable differences in population, geography, history, and culture present daunting challenges to any effort to attain uniform results nationwide.

_________________________

1 In this context, “state” refers to the 50 states of the United States, as well as its territories. See Box 1-2: Notes on Terminology for more information.

The addition of broader social goals to the EPSCoR mission—as compelling and justified as these broader social goals may be—dilutes the program’s ability to advance its primary goal of strengthening research capability and providing research opportunities for postsecondary students.

The breadth and increasing complexity of the EPSCoR program objectives have made it difficult to develop a rigorous assessment system with quantitative metrics to evaluate short-term and, more important, long-term progress. In addition, neither Congress nor the agencies have required this type of assessment, so there has been little incentive to do so.

Nevertheless, there is evidence that the EPSCoR programs have provided significant benefits to participating states—and thus to the nation. Under the America COMPETES Reauthorization Act of 2010,2 Congress requested that the National Academy of Sciences examine EPSCoR with funding from NSF. The committee’s charge was to assess the effectiveness of NSF’s EPSCoR program and similar programs administered by other the federal agencies, including the extent to which these programs achieved their respective goals and states used these awards to improve their science and engineering research, education, and infrastructure.3

For at least two reasons, the committee could not assess the effectiveness of EPSCoR with the necessary rigor needed to fully address Congress’s charge. First, the overall mission of EPSCoR and its counterparts has broadened over time and to varying degrees, depending on the respective federal agency. In addition to the changes in the overall environment for conducting research, this may have affected the program’s overall progress in achieving its goals. Second, data of sufficient quality on program operations and expected outcomes are not currently available and would have required more time and resources to collect than were at the Committee’s disposal.

Therefore, the committee focused on better understanding the extent to which the overall structure and policies have affected the program’s ability to achieve its overall mission and major goals.

The first EPSCoR program began more than three decades ago at the National Science Foundation, which is mandated in its founding legislation not only to promote national excellence in science but also to avoid its “undue concentration.” When several members of Congress complained that a small number of states were receiving a disproportionate share of NSF research funding, the agency responded by creating its EPSCoR program. It began in 1979 by distributing $1 million among five states with demonstrated subcompetitive ability to attract National Science Foundation research and development (R&D) funds to help them develop strategies to enhance their research competitiveness. NSF subsequently provided support to implement

_________________________

2 America COMPETES Reauthorization Act of 2010 (111th Congress, 2009–2010, April 22, 2010), http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr5116.

3 The complete statement of task and congressional mandate can be found in Appendix C.

these strategies for 5 years. The expectation was that when the funding came to an end, these states would be capable of competing successfully for research funding from NSF’s general merit-based grant pool. Instead, those states are still receiving EPSCoR funds, and the program has expanded to include many more states.

NSF EPSCoR’s annual budget now stands at roughly $150 million, and eligibility for the program has spread across 32 jurisdictions, including 29 states and 3 territories (Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands). In addition, NIH, DOE, USDA, and NASA together provide approximately $325 million in funding per year. The NIH and USDA have different eligibility criteria, and a slightly different group of states participate in these programs. The Department of Defense (DOD) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also operated programs for several years, but these agencies have terminated funding.

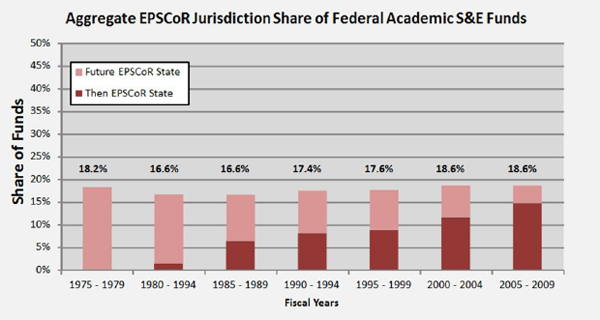

In retrospect, the initial NSF EPSCoR goal seems politically astute but unrealistic. Several million dollars of funding and 5 years of effort were clearly not going to transform a state’s research capacity or make it competitive with other states that had invested and/or received tens of millions of dollars over decades to build their research capacities. Indeed, EPSCoR has been in operation for more than 30 years and, over this period, the program has invested several billion dollars in capacity-building activities, yet the same 10 states that received the highest level of research funding in 1977 still top the list. Moreover, more than half of all states now receive EPSCoR funds, and no state that has participated in the program has permanently “graduated” from it. Analysis also shows EPSCoR-eligible states received roughly the same percentage of total federal research funding in 2012 that they had received in 1979 (see Figure S-1).

EPSCoR programs and EPSCoR states have devoted considerable time and resources to building research capacity. Yet, the states that have been the nation’s traditional leaders have also invested in their research capacity—deriving considerable funds from both public and private sources. As a result, historically successful states continue to do well in competing for research support. It should also be noted, however, that the EPSCoR states have not lost ground, and it is clear that virtually all have improved their research capacity in absolute, if not relative, terms. Nevertheless, because EPSCoR funding constitutes a relatively small percentage of each EPSCoR state’s total research funding, the precise role that the programs have played in this effort is difficult to determine.

Figure S-1. The share of federal academic science and engineering funds received by EPSCoR states has remained largely the same since the inception of the EPSCoR program. [SOURCE: NSF Survey of Federal Science and Engineering Support to Universities, Colleges, and Nonprofit Institutions via WebCASPAR].

The reason for the growth in the number of participating states is that the criterion for eligibility has been relaxed over time. NSF EPSCoR permits any state that receives less than a set percentage of NSF funding to be eligible for the program, and that percentage has been increased over time. All the other agencies except NIH and USDA closely follow the NSF lead. NIH initially admitted states where the success rate of research proposals was less than 20 percent, but it is now proposing a shift to a system that would admit all states that fall below the median in total NIH research funding. When total funding is the criterion for eligibility, state population becomes the dominant factor in determining a state’s eligibility. NSF admits any state that receives less than 0.75 percent of its funding. Sixteen states have less than 0.75 percent of the U.S. population. To lose their eligibility and graduate from the program, each of these states would have to receive a percentage of research funding that exceeds its share of the nation’s population. Indeed, several states have less than 0.25 percent of the nation’s total population, and it will be virtually impossible for these states to ever reach 0.75 percent of total funding.

If one is aiming for equity among all the states, it might therefore make more sense to look at per capita federal research spending in each state. Indeed, the ranking of states by per capita funding differs significantly from the ranking by total funding, and several current EPSCoR states appear in the top 10 on this list. Although the committee is not recommending that per capita research funding be the sole criterion, it does believe that per capita funding should be a primary consideration.

The committee also believes that a state’s commitment to research—expressed in visible and concrete terms—should be one of the main criteria for

competitive federal support. Unless a state invests its own energy and resources in improving its research capacity, the federal commitment will not have the desired effect of creating an enduring foundation for excellence. As a result, the committee recommends that all EPSCoR funding should require some level of state matching funds and that the level of state commitment should be a key criterion in awarding competitive grants.

All decisions about where to invest research resources are difficult, and all involve trade-offs. For the EPSCoR programs, the worry is that the agencies are compromising their commitment to merit review of research proposals. But the trade-off is relatively modest. Less than $500 million in a total federal academic research budget of more than $30 billion is devoted to EPSCoR. Determining its absolute value, however, is inherently difficult. The committee learned of many individuals from EPSCoR states who have produced important research results and many institutions in those states that have graduated successful scientists and engineers.

The committee also found that there has not been a rigorous quantitative assessment of the EPSCoR programs that would document their value. The assessment that will have to be done should include: (1) identifying the data needed to address the important questions posed by Congress; (2) selecting and executing an appropriate evaluation design; and (3) collecting, analyzing, and interpreting the necessary data. Judgments could then be made regarding the extent to which EPSCoR was efficiently implemented, how well it achieved its stated goals, and its overall effectiveness in advancing the ultimate mission of enhancing and broadening research capacity. Such a study could in no way have been accomplished within the timeline and resources available to the committee.

With these caveats and restrictions in mind, the committee has arrived at the following findings and recommendations.

The committee supports the continuation of programs that support the proposition stated in the America COMPETES Act:

“The Nation requires the talent, expertise, and research capabilities of all States in order to prepare sufficient numbers of scientists and engineers, remain globally competitive and support economic development.”

America COMPETES Reauthorization Act of 2010 (111th Congress, 2009–2010, April 22, 2010), http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr5116.

Findings

• The talent necessary to succeed in science and engineering resides in all states. Thus, it is in the national interest for the federal government to

support efforts to develop and utilize this talent to enhance national research capacity.

• EPSCoR programs are a part of a broader national and global research enterprise.

• Congressional changes in state eligibility requirements and congressional mandates to agencies to create EPSCoR-like programs have resulted in multiple and often competing objectives and policy directives by participating agencies.

oCurrent eligibility criteria have led to more than half the states being included, blurring the programs’ objectives and reducing the likelihood of their success.

oPatterns of eligibility do not align well with other indicators of capacity, such as state population or number of research-intensive universities. As a result, outcomes are difficult to assess, especially on a comparative basis.

• EPSCoR programs have enhanced the nation’s human capital by strengthening research infrastructure and by training many future scientists and engineers in states where, in some cases, training opportunities had been scarce and largely inadequate prior to the program’s arrival.

• There is some evidence that the EPSCoR programs have not been a good fit for the mission agencies. For example, EPA and DOD terminated their EPSCoR programs. However, the mission agencies are the major source of engineering research funding and therefore critical to engineering education.

• State-level commitments to enhancing research capacity are uneven across the participating states. The effectiveness of state committees in NSF EPSCoR states is also uneven.

• There is considerable variation in agency programs, review processes, and the role and composition of state committees. Further, the NIH IDeA program does not formally involve the state committee in its implementation, although informal interactions do occur.

• The aggregate share of federal R&D to eligible states has not changed significantly over the course of the program. There is also considerable variation among states in their progress toward a more competitive posture. In the aggregate, eligible states continue to be less successful in garnering NSF funding than are other states.

• Nearly all participating states report positive cultural change in attitudes toward science and engineering as a consequence, at least in part, of EPSCoR programs. Similarly, they also report positive organizational, policy, and program changes that have enhanced their research environment. Further, there is evidence that research capacity in eligible states has increased (although not enough in most cases to change their relative standings). There is anecdotal evidence that EPSCoR programs

have contributed to this result, but the magnitude of their contribution is difficult to determine.

• The evaluation efforts of the EPSCoR-type programs leave much to be desired. To date, such efforts have relied on incomplete and inconsistent assessment of program designs and on metrics that do not allow for comparisons of effectiveness.

Recommendations

The committee recommends that the federal government continue to promote the development of research capacity in every state so that all citizens across the nation have the opportunity to acquire the postsecondary education, skills, and experience they need to pursue productive and successful careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields and to contribute fully to the nation’s research enterprise.

With that in mind, the committee recommends the following actions to create a more focused program with greater impact.

• EPSCoR programs should concentrate on the programs’ core elements:

oTo enhance research excellence through competitive processes.

oTo enhance capacity for postsecondary training in STEM fields.

• EPSCoR programs should be restructured to combine beneficial aspects of current programs:

oThe NIH and NSF EPSCoR programs should pursue a “blended” funding strategy with two tracks:

![]() A competitive-grant track that provides fewer and larger grants that are evaluated first for scientific merit and that are intended to produce focal points of research excellence and research opportunities for junior as well as senior faculty.

A competitive-grant track that provides fewer and larger grants that are evaluated first for scientific merit and that are intended to produce focal points of research excellence and research opportunities for junior as well as senior faculty.

![]() A smaller-scale, infrastructure investment or statewide investment track that works with state committees to ensure that every state has the capacity to provide advanced education and research experience.

A smaller-scale, infrastructure investment or statewide investment track that works with state committees to ensure that every state has the capacity to provide advanced education and research experience.

oDOE, NASA, and USDA should develop strategies to help meet the mandate laid out in the America COMPETES Act that all mission agencies support postsecondary education in STEM disciplines.

• The EPSCoR programs, working through the EPSCoR Interagency Coordinating Committee (EICC), should develop and enforce a realistic framework for state eligibility and graduation from the program:

oThe 0.75 percent criterion fails to account for population and other critical aspects of research capacity and competitiveness. New graduation and eligibility criteria should be developed and implemented that could consider:

![]() Population.

Population.

![]() State commitment.

State commitment.

![]() Proposal success rates per research-university faculty member.

Proposal success rates per research-university faculty member.

![]() Total research funding.

Total research funding.

![]() Progress to date and future opportunities for progress.

Progress to date and future opportunities for progress.

![]() Financial need.

Financial need.

• The committee recommends that the agencies, cooperating through the EICC, reset the guidelines and that all states must reapply for eligibility after the expiration of their current EPSCoR grants.

• The proposal review for prospective EPSCoR projects should be made more rigorous to:

oEnsure that reviews of the scientific merit of the proposals are conducted by the most highly qualified panels of experts in the field of study. Scientific merit should be the first consideration in any assessment of a proposal’s strength and value. Specifically, all proposals should be reviewed in a two-step, sequential process.

![]() First, a review of the proposal’s scientific merit—a “science score.”

First, a review of the proposal’s scientific merit—a “science score.”

![]() Second, a review of the proposal’s potential (state, agency, societal) impacts—a “program score.”

Second, a review of the proposal’s potential (state, agency, societal) impacts—a “program score.”

oRequire some level of matching contribution for all research awards to ensure that the state is involved and committed to the project.

![]() Sources dedicated as matching funds can be from the state, the university, the private sector, or other sources.

Sources dedicated as matching funds can be from the state, the university, the private sector, or other sources.

• The evaluation process conducted during and after an EPSCoR project’s implementation should be made more rigorous by:

oDeveloping and implementing an effective third-party evaluation design that is reliable and valid and that is consistent with other federal evaluation approaches, such as those developed by the Office of Management and Budget.

In conclusion, the committee recommends that the newly refocused federal programs be renamed to better reflect their mission and to remove “experimental,” which is now a misnomer.