Research Needs in Support of Understanding Ecosystem Services in the Gulf of Mexico

INTRODUCTION

As has been discussed throughout this report, the concept of ecosystem services offers the potential to view human-ecosystem interactions in a holistic fashion that may provide decision makers with broadened opportunities to understand the impacts of natural and human-caused events in complex systems such as the Gulf of Mexico (GoM). An ecosystem services approach to damage assessment may also offer managers a broader array of restoration options as well as strategies to ensure long-term resilience. Although an ecosystem services approach to damage assessment offers many advantages, its application in real-world situations faces a number of challenges, many of them revolving around a limited mechanistic understanding of the detailed linkages and interactions in an ecosystem as complex as the GoM. Other fundamental challenges involve how to relate changes in the ecosystem directly to benefits (or deficits) in human well-being and how to manage the potentially complex tradeoffs among the benefits (or deficits) when selecting from various restoration strategies.

Some ecosystem services are well defined and well documented—for example, wetland mitigation of storm impacts or contribution to fisheries production (see Chapter 5). For some of these well-defined ecosystem services, methods exist to establish a monetary value of the service, which provides one measure of benefits. For less-well-defined ecosystem services, the understanding of relationships between ecosystems and the value humans derive from them is still in a nascent stage. Considerations of ecosystem services are particularly important in the GoM region, where the livelihoods and lifestyles of many coastal communities have been closely tied to access to and quality of GoM ecosystems, often for multiple generations.

Previous chapters have outlined many of the challenges to application of an ecosystem services approach to understand the impact of an event such as the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill on the GoM ecosystem. This final chapter focuses on the question posed in Statement of Task 8: “What long-term research activities and observational systems are needed to understand, monitor, and value trends and variations in ecosystem services and to allow the calculation of indices to compare with benchmark levels as recovery goals for ecosystem services in the Gulf of Mexico?” In the fleshing out of these research and observational needs, it is hoped that the groundwork will be laid for establishing methodologies that will facilitate the application of an ecosystem services approach in the GoM and other ecologically sensitive regions.

CONTEXT OF RESEARCH IN THE GULF OF MEXICO IN LIGHT OF THE DWH OIL SPILL

Directives and Funding for Restoration

Long-term research and data collection activities to support an ecosystem services approach to GoM management will be conducted in a framework of legislative directives and focused funding that stem from government actions and monetary settlements resulting from the DWH oil spill.

To supplement the traditional Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) process (see Chapter 2), which began almost immediately after the spill, President Obama directed, through Executive Order 13554, the establishment of the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Task Force and charged it with developing a “Gulf of Mexico Regional Ecosystem Restoration Strategy” within a year of the order.1 This strategy (Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Task Force, 2011) proposed a science-based Gulf Coast ecosystem restoration agenda, which included goals for ecosystem restoration, development of a set of performance indicators to track progress, and a means of coordinating intergovernmental restoration efforts guided by shared priorities. Federal efforts were to be efficiently integrated with those of local stakeholders, and a particular focus was to be given to innovative solutions and complex, large-scale restoration projects. The strategy also identified the monitoring, research, and scientific assessments needed to support decision making for ecosystem restoration and to evaluate existing monitoring programs and gaps in current data collection.

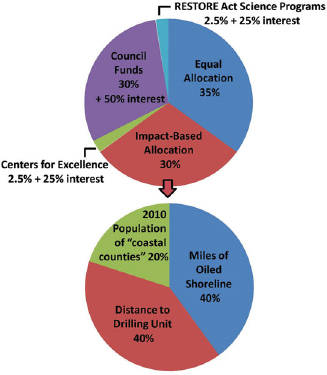

The U.S. Congress passed the Resources and Ecosystem Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States Act of 2012 (RESTORE Act) on June 29, 2012, and President Obama signed it into law on July 6, 2012. The RESTORE Act allocates 80 percent of the administrative and civil penalties levied under the Clean Water Act (CWA) to the Gulf Restoration Trust Fund within the Treasury Department (Figure 6.1). The remaining 20 percent of the CWA fines will go to the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund. The amount of civil penalties that may be recovered, as well as the timing of recovery, is currently unknown, but it is very likely that the amount will involve billions of dollars.

Thirty percent of the RESTORE Act funds will be managed by the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council, an entity that replaced the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Task Force through an Executive Order dated September 10, 2012.2 The Council is charged with developing a comprehensive plan for ecosystem restoration in the Gulf Coast (Comprehensive Plan), that includes “identifying projects and programs aimed at restoring and protecting the natural resources and ecosystems of the Gulf Coast region, to be funded from a portion of the Trust Fund; establishing such other advisory committees as may be necessary to assist the Gulf Restoration Council, including a scientific advisory committee and a committee to advise the Gulf Restoration Council on public policy issues; gathering information relevant to Gulf Coast resto-

_________________

1 Exec. Order No. 13554, 75 Fed. Reg. 62313 (Oct. 8, 2010). Available at http://www.epa.gov/gcertf/pdfs/GulfCoastReport_Full_12-04_508-1.pdf.

2 Exec. Order No. 13626, 77 Fed. Reg. 56749 (Sept. 10, 2012).

FIGURE 6.1 Distribution of RESTORE Act funds. SOURCE: Based on Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy (2013).

ration, including through research, modeling, and monitoring; and providing an annual report to the Congress on implementation progress.” Thirty-five percent of the RESTORE Act funds will be divided equally among the five impacted states for ecological restoration, economic development, and tourism promotion; 30 percent will be divided among the states according to a formula to implement individual state expenditure plans as approved by the Council; 2.5 percent will be given to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for a monitoring, observation, and technology program; and the final 2.5 percent will be used by the five impacted states for the establishment of research centers of excellence. The CWA is only one of the potential grounds for statutory liability for damage caused by the spill for the responsible parties; the Oil Pollution Act, discussed below, is another.

In May 2010, BP Production and Exploration committed $500 million over a 10-year period to create a broad, independent research program to be conducted at research institutions primarily in the Gulf Coast states.3 BP initially granted year-one block grants in June 2010 to Gulf

_________________

Coast state institutions and the National Institutes of Health to establish critical baseline data as the foundation for subsequent research as well as to support study of the health of the oil spill workers and volunteers. Smaller “bridge” grants, totaling $1.5 million, were awarded in the summer of 2011, allowing researchers with National Science Foundation (NSF) Rapid Response Research (RAPID) grants to complete their research. The first major competition for research consortia was completed in fall 2011, with the awarding of $112.5 million in grants to eight research consortia. These consortia completed their first year of activities in December 2012. Smaller investigator grants totaling $22.5 million were awarded in fall 2012.4 A new request for proposals for research directed to larger overall research questions will entertain proposals in the early part of 2014 for the next 3-year period.5

Additionally, a November 5, 2012, settlement between the U.S. Department of Justice and BP Exploration and Production, for the latter’s guilty plea for a number of violations related to the Macondo blowout, provides several billion dollars for restoration, research, education, outreach, and monitoring.6 An additional settlement between the U.S. Department of Justice and Transocean Deepwater Inc. was reached on February 14, 2013, regarding Transocean’s violation of the CWA via the DWH oil spill.7 Included in these two settlements were awards of nearly $2.5 billion dollars to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to remedy harm and eliminate or reduce the risk of future harm to Gulf Coast natural resources and $500 million dollars to the National Academy of Sciences for a program focused on human health and environmental protection, including issues relating to offshore drilling and hydrocarbon production and transportation in the GoM and on the Outer Continental Shelf.

Additional research funds are being provided by federal entities, states, nongovernmental organizations, and private foundations. For instance, almost immediately following the spill, the NSF made available significant funds from its programs to support DWH oil spill research. More than 150 RAPID grants and Major Research Instrumentation (MRI) RAPID grants were awarded to ocean scientists for research directed to certain aspects of the spill. Subsequent NSF funding has been awarded through the competitive grants system. Thus, from an unprecedented environmental event, significant funding has become available to conduct research across a broad spectrum of issues.

The final amount of funds to be directed to various activities through potentially numerous avenues depends on the outcome of legal proceedings between the Department of Justice and the responsible parties. The NRDA process and fines determined under the Oil Pollution Act, the establishment and collection of penalties under the CWA, and plans for Gulf Coast restoration create unprecedented opportunities for research and restoration, to address not only the damage caused by the spill but also the longer-term impacts of a number of human activities on the GoM ecosystem. Restoration will directly respond to damages from the spill, but it offers the opportunity for a system recovery that considers human and natural systems resilience.

_________________

4http://www.unols.org/meetings/2010/201010anu/201010anuap09.pdf.

5http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/2013/save-the-date-gomri-rfp-for-2015-2017-research-consortia.

6http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2012/November/12-ag-1369.html.

7http://yosemite.epa.gov/opa/admpress.nsf/0/B80C763F3BFC11A385257B1200788616.

Finding 6.1. The funding from the settlements stemming from the DWH oil spill, coupled with public- and private-sector investment, present an unprecedented opportunity to create research and restoration programs that could establish a level of understanding and baseline information about the GoM that may overcome the challenges faced in fully evaluating ecosystem services in this vulnerable region.

Research Activities

The early recognition of the DWH oil spill as an environmental disaster of unprecedented proportion led to a rapid response by researchers from many sectors. As outlined in the Interim Report (NRC, 2011), immediately after the spill began, the federal government initiated a large-scale sampling program to fulfill its obligation to assess the injury to the public under the NRDA process. The data collected in support of NRDA represent some of the most comprehensive sampling that has ever been done in the GoM. As discussed in the Interim Report and in Chapter 2, these data are intended to support traditional damage assessment approaches (i.e., losses are generally measured in simple ecological terms rather than in terms of reductions in the value of ecosystem services), and therefore may not be directly useful for enhancing our understanding of ecological production functions and ecosystem services. Data collection and analyses continue under NRDA, and some of the data have been made public,8 but many of the results will remain confidential until litigation is complete. Nonetheless, once fully available to the public and the research community, the NRDA data sets will inevitably be an invaluable addition to the overall database and understanding of the GoM.

Along with the federal government, researchers from private industry, universities, research institutions, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) moved as quickly as possible to begin the scientific assessment of the oceanic and onshore processes and impacts. Methodologies included collection of biota census data (with multiple variables), the Before and After Control Impact (BACI) approach (in those situations where scientists were able to assess habitats before and after exposure to the oil), comparisons of assorted environmental variables to long-term data, if available, and deployment of sensitive and state-of-the-art instrumented arrays in the deep ocean and atmosphere. Although the process is still young, the research results, unless confidential, are being published with unprecedented speed in highly respected peer-reviewed journals. The research will continue, and findings about the impacts of the spill and the fate of the GoM ecosystem will be communicated for years to come. However, at some point in time, the mandate for the liable entities and the resource managers to conduct oil-spill-related research and interpret the findings will most likely be removed.

As outlined above, the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) has funded eight regionally led consortia to conduct leading-edge research on the GoM. GoMRI, in cooperation with a Research Board, administers the research funds to ensure high scientific standards and to isolate the research programs from the funding source. Research projects focused on the following tasks:

_________________

1. Physical distribution, dispersion, and dilution of petroleum (oil and gas), its constituents, and associated contaminants (e.g., dispersants) under the action of physical oceanographic processes, air-sea interactions, and tropical storms.

2. Chemical evolution and biological degradation of the petroleum/dispersant systems and subsequent interaction with coastal, open-ocean, and deep-water ecosystems.

3. Environmental effects of the petroleum/dispersant system on the seafloor, water column, coastal waters, beach sediments, wetlands, marshes, and organisms; and the science of ecosystem recovery.

4. Technology developments for improved response, mitigation, detection, characterization, and remediation associated with oil spills and gas releases.

5. Impact of oil spills on public health.

Finding 6.2. The current research directions have the potential to greatly enhance our understanding of the GoM ecosystem. If these efforts directly address the quantification of ecosystem services, then the results of the research will better serve to improve management and the long-term health of the GoM system.

Research Background and Plans for the Gulf of Mexico

This section reviews what research is currently being planned and, from the perspective of ecosystem services, what additional efforts might enhance our understanding of the GoM ecosystem services and their value to the well-being of the people of the region.

Response Technologies

At the advent of the DWH oil spill, of immediate concern was how to stop the flow of oil, which was pouring out at a rate of up to 60,000 barrels per day, and possibly more (McNutt et al., 2012), from a wellhead located 1,500 m below the sea surface. Additional concerns centered on how to prevent the spread of oil at the surface and into coastal waters and onto coastal landforms, as well as how to deal with the oil that made landfall. In the history of oil spill cleanup, a variety of response technologies and techniques have been developed. Some have proven more effective than others, and all need to be examined and applied in the context of prevailing environmental, habitat, and oiling conditions.

Chapter 4 of this report provides a detailed examination of the response technologies used for the DWH oil spill and their relative effectiveness. The questions and controversy surrounding the use of emerging technologies (e.g., subsurface injection of dispersants and in situ burning) during the spill highlight the need for new research, particularly to accurately predict the impact of dispersants on biodegradation rates and the long-term effects of dispersed oil on the food web and on ecosystem services.

The American Petroleum Institute has issued a request for proposals for the study of the use of dispersants at depth, and one of the eight GoMRI consortium programs (C-MEDS) is

focusing entirely on the chemistry of dispersants.9 Specific topics outlined in the C-MEDS research task include the design of porous particles that would stabilize at the oil-water interface and deliver dispersant and biological nutrients, the use of computational methods to establish the self-assembly of surfactants at conditions of high pressure and low temperature and to understand dispersant configuration at the oil-water interface, and the use of natural biologically derived surfactants that are hydrophobin-based proteins or polysaccharides such as cactus mucilage. A recent paper by Paris et al. (2012) concluded that the injection of dispersants into the wellhead did little to increase dispersion of the oil beyond what was already occurring from effects of shear emulsification. However, the literature review presented in Chapter 4 suggests that this is an unresolved issue in need of further investigation.

The fate and transformations of oil from the DWH oil spill will continue to be influenced by natural attenuation processes. Continued observations, monitoring, and research of these processes, especially in relation to technological countermeasures, are warranted. Needed are further studies that use realistic initial dispersed oil concentrations and that avoid boundary effects that increase oil-dispersant concentrations. The effectiveness and net benefits of many of the response technologies varied because of environmental conditions (such as the sea surface conditions, currents, and depth of the wellhead) as well as the timing of their application. Additional research and experience will refine and enhance the effectiveness of any of these technologies—with the ultimate goal of reducing their impacts as well as the spill’s impacts on ecosystem services.

Decision Science Tools

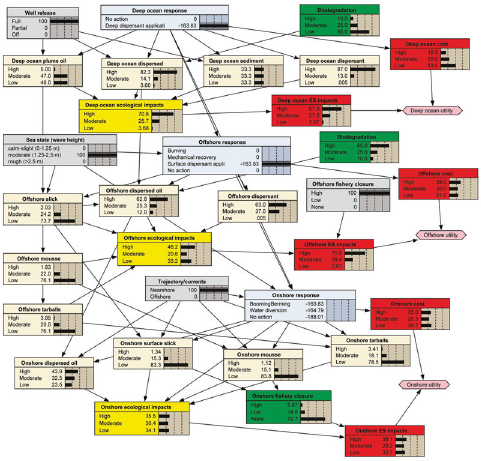

Ultimately, the decisions made about the use of response technologies will be tied into a net environmental benefit analysis (NEBA) (see Chapter 4). The extension of these analyses is the construction of “influence diagrams,” a graphical network showing probabilistic relationships and how decisions are likely to affect various outcomes (see Figure 6.2).

In retrospect, influence diagrams could have helped in the consideration of resource value and potential risk during the development of decision models for emergency response prior to the spill (Carriger and Barron, 2011). For such diagrams to be reliable, an understanding of the mechanistic linkages among ecosystem processes is required. The technologies used to respond to the DWH oil spill and the data from the associated impacts derived from continued research should assist in the creation of these diagrams.

An interactive, layered-mapping Web application called ‘SPECIESMAP’ has been designed to help fill knowledge gaps regarding potential DWH oil spill impacts to fish species such as relocation of spawning grounds, bioaccumulation of hydrocarbons, altered migration routes, expanding hypoxic dead zones, affected life-history stages, reduced populations, and extinctions (Chakrabarty et al., 2012). Additionally, influence diagraming would have benefited from information about the circulation of water masses within the GoM—another identified knowl-

_________________

FIGURE 6.2 Influence diagram for the DWH oil spill. SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Carriger and Barron (2011).

edge gap—because there were fears that some of the oil from the DWH oil spill would pass through the Straits of Florida and contaminate the Atlantic. There is, however, no evidence that such oil passage occurred.

The government of Mexico raised concerns that oil residuals would enter Mexican waters. Recent modeling of the spill (Le Henaff et al., 2012) has shown that currents created by southerly winds drove the surface oil toward the northern shores of the GoM. These winds prevailed for the first 15 days after the blowout on April 20, 2010, and returned in June and July, which minimized the amount of oil entrained by the Loop Current and drawn into the central Gulf,

so no oil impacted the shores of southern Florida or Mexico. Had information of this sort been appropriately incorporated into the decision-making process at the time of the spill, many unwarranted concerns could have been addressed.

Consequently, along with research on the specific impact of a particular response technology (e.g., the effect of dispersants on biodegradation), research is needed to fill the knowledge gaps associated with our understanding of ecosystem dynamics, which is discussed in the next section.

Finding 6.3. The response technologies applied during the DWH oil spill resulted in both beneficial and detrimental effects on ecosystems and the services they provide to humans. The development of additional guidelines to improve the effectiveness of various technologies, and protocols to monitor the impacts on ecosystems and the services they provide, are of paramount importance. The decisions that determine when and where to apply these technologies are guided by decision science tools such as net environmental benefit analyses and influence diagrams, which can only be effective if there is an understanding of the mechanistic linkages among the ecosystem processes.

Background Research and Data

At the onset of the DWH oil spill, there was great concern about the lack of background research and data, particularly for the blue-water GoM and the deep-water environments of the blowout area. Subsequent efforts to collect data revealed that, for some areas and some variables, a significant amount of pre-spill data were available, but for others, pre-spill data were severely lacking. In some cases, the lack of an organizing structure and aggregated body of knowledge to make sense of the data was more limiting than the lack of data per se.

The former Minerals Management Service (now Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, BOEM) has supported deep-water GoM research since the early 1970s. The Department of the Navy funded earlier zoological expeditions to the deep GoM. Although found primarily in grayliterature reports, this information is available. As a result of the BOEM Environmental Studies Program’s historic and continuing efforts, the GoM is one of the more extensively sampled regions of the world’s oceans, yet this sampling represents only a tiny fraction of the region’s volume. Although many data gaps and inadequately addressed phenomena exist, a basic level of understanding has been established for the continental shelf and the deep basin (see Chapter 5, “The Deep Gulf of Mexico”). Similarly, research on methane seeps, related processes, and the biodiversity of organisms on escarpments, salt domes, and hard banks throughout the deeper GoM is further advanced than for many other deep oceans and is continuing. Much of the research on oil and methane seeps has been funded by NSF as well as BOEM. Genomic data from biodiversity studies of the shelf edge and slope banks are stored at GenBank10 and BOLD (Barcode of Life)11 and are fully available to the public.

_________________

Requirements for data collection, data quality control and assurance, and transfer of data with appropriate metadata to funding agencies have changed dramatically since the early 1970s, when baseline data for the GoM became an area of emphasis in the advent of oil and gas drilling and development. There was no consistent mechanism for reporting of data or metadata for many survey-type data collections such as BOEM-funded work, the fishery-independent data of the Southeast Area Monitoring and Assessment Program (SEAMAP), and many other programs in the GoM. There have been improvements in data quality assurance/ quality control, methods to relay data to designated national data repository systems, Federal Geographic Data Committee metadata requirements, Data Management and Control methods to submit oceanographic data to the Integrated Ocean Observing System and the numerous regional associations, such as the Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ocean Observing System Regional Association (GCOOS-RA) and the Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association (SECOORA), and specific mechanisms for shared open-source modeling components. It would be difficult to incorporate historic data into the new data compliance systems, but the opportunity to do so may exist in the overall need for historic data to be made available.

Less is known about the open-water ecosystem and the deep GoM, but NOAA and special BOEM-funded studies have collected long-term observational data on marine mammals. Planktonic data from NOAA fisheries surveys are part of the National Ocean Data Center or other federal data repositories. More recent tagging studies of bluefin tuna (Census of Marine Life12 and listed publications) revealed migration patterns and a breeding area in the GoM, but much remains unknown about their larval and early life history. Background data are missing for many components of the open GoM; for example, mesopelagic fish populations and their ecology are poorly documented.

SEAMAP is a state-federal-university program for collection, management, and dissemination of fishery-independent data and information in the southeastern United States. Major activities in the GoM include surveys of shrimp, groundfish, and ichthyoplankton, collection of environmental and benthic data, mapping of live and hardbottom areas, investigations of low oxygen and other environmental perturbations, and establishment of a regional, user-friendly data management system that can be accessed by all marine management agencies in the southeastern United States. The GoM SEAMAP effort was implemented in 1981 (Eldridge, 1988), and large databases archiving the results of the field and laboratory efforts are maintained by SEAMAP in Pascagoula, Mississippi.13 These data provide a long-term assessment of numerous organisms in the GoM.

BOEM requires ADCP (acoustic Doppler current profiler) data from any floating platform in the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf leasing areas in water depths of 400 m or greater. These data provide important input for circulation models. Other coastal ocean observing platforms exist in the GoM (see Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ocean Observing System14 and SECOORA15 for the location and data products generated from these systems). Furthermore, there are many satellite

_________________

observing systems, ocean modeling efforts, and interpretation activities in the GoM. Over the past several years, SURA (Southeastern Universities Research Association) has funded a “Super Regional Testbed to Improve Models of Environmental Processes on the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Coasts,”16 specifically research of and transition to operations models of estuarine hypoxia, shelf hypoxia, and coastal inundation. The shelf hypoxia effort used multiple physical and coupled physical-biogeochemical models, including the U.S. Navy’s regional circulation prediction system for the GoM and Caribbean, as a baseline operational capability, along with other physical models for the northern GoM. The findings of this project will be published in the Journal of Geophysical Research in 2013.

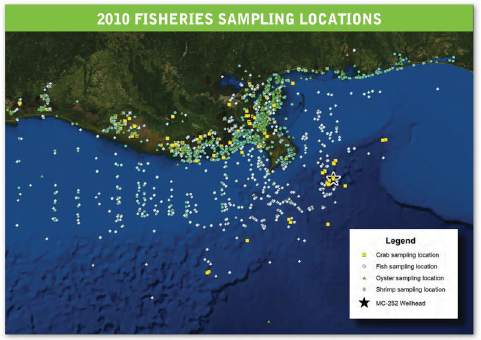

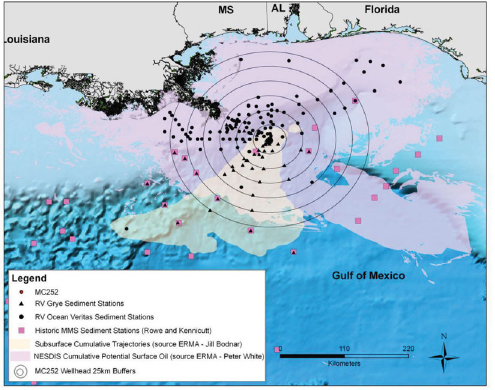

Some of the best data taken as background to the oil spill, at least in the near-shore area as pre-exposure conditions, were collected before the oil reached the shoreline and served as a basis for the eventual NRDA by the Trustees under the Oil Pollution Act. As noted earlier, these data collections continue, but many of the results are being held in confidence until litigation is complete. The NRDA of DWH oil spill extends beyond previous deep habitat descriptions of the GoM (e.g., benthic faunal inventory and biodiversity). The NRDA collection of data in the deep sea has been intensive and spatially dense for the benthos as well as for full water column faunal inventories, resulting in much better information about these previously understudied systems. Figures 6.3 and 6.4 illustrate the numerous types and distributions of samples that will support the NRDA process as well as provide a large reservoir of background data, because not all sites will have been exposed to Macondo oil. As indicated earlier, NRDAs are primarily based upon traditional damage assessment approaches and may not be useful for enhancing the understanding of ecological production functions and ecosystem services. The eventual deposition of these data and the data generated by the GoMRI research programs into national ocean data repositories or their equivalent will provide much-needed “background” data for the northern GoM.

Finding 6.4. A broad spectrum of background pre-spill data has been collected as part of the NRDA process. The NRDA data, once released to the public, should contribute significantly to the body of background data that can help to characterize much of the GoM.

Recently, Murawski and Hogarth (2013) evaluated the state of current observational programs in the GoM and concluded that some programs provide “adequate” baseline data for the following parameters: annual extent of hypoxia off Louisiana; some water quality and pathogen metrics; population abundances of some fishery and protected species; sea level height; conductivity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and nutrient levels; and primary productivity, land-use, and wetland landscape change trends from satellite imagery. They also concluded that adequate observational data do not exist for contaminants in water and sediment; polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and metabolites in seafood; fundamental health data on fish, mammals, turtles, invertebrates, and deep ocean benthic communities; and the economic, social, and public health of the Gulf Coast. Although they pointed to a lack of fishery-indepen-

_________________

FIGURE 6.3 Overview of offshore and deep-water stations sampled on recent (2010) Gyre and Ocean Veritas cruises and prior (2000–2002) MMS (now BOEM)-sponsored cruises (Rowe and Kennicutt 2009, Deep Gulf of Mexico Benthos sites). NOTES: Rings centered around the wellhead are 25 km apart. Sediment samples were collected with multicorers at all sites. SOURCE: Deepwater Benthic Communities Technical Working Group (2011).

dent, population abundance data and distribution data for turtles and marine mammals, these data do exist—that is, from SEAMAP,17 NOAA,18 and the NRDA process. Additionally, fundamental oceanographic and meteorological data are provided by moorings of the National Data Buoy Center19 and the ADCP current meter measurements from offshore oil and gas platforms.

In summary, many groups in the GoM are building on existing data sets, ocean observing capabilities, and continuing basic observational data. For some parameters, observational data are adequate, but for others, more robust measurements are needed. In addition, current and future funding will not be sufficient to collect a full suite of background data to support mitigation of any potential disaster. Given the oil and gas reserves of the GoM, however, certain basic

_________________

17http://sero.nmfs.noaa.gov/grants/seamap.htm.

18https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/marine-mammals-turtles/index.

FIGURE 6.4 Priority stations from fall 2010 response cruises (Gyre and Ocean Veritas) that were selected for the initial suite of macrofaunal and meiofaunal analyses. NOTE: Rings centered around the wellhead are 25 km apart. SOURCE: Deepwater Benthic Communities Technical Working Group (2011).

data should be collected as a part of a systematic monitoring system. There have been several efforts to compile background information during and after the oil spill, including the NOAA Deepwater Horizon Archive,20 the Joint Analysis Group for Surface and Sub-Surface Oceanography, Oil and Dispersant Data,21 and Naval Oceanographic Office Special Support-GOMEX Mississippi Canyon 252 Oil Spill.22 There is, however, no integrative superstructure or roadmap to available data, the development of which will be even more essential as new data arrive from current and future research activities.

Despite the tremendous amount of funding that will be available to GoM researchers, there will likely never be enough to support all of the potentially important assessment and

_________________

20http://www.noaa.gov/deepwaterhorizon/.

monitoring activities needed to capture the state and function of the GoM’s natural and social systems. The necessary types and amounts of baseline data that may be suddenly needed when there is an environmental disaster cannot be fully anticipated. However, as seen with the DWH oil spill, although there was an existing cache of long-term and baseline data, it was neither tabulated and synthesized nor accessible from a unified data system. With the advent of the DWH oil spill, build-out plans for physical, chemical, and biological monitoring, such as documented by the GCOOS-RA, provide a structure upon which to begin building the necessary framework for identifying baselines, physical forcing, biological communities, and ecosystem functions (Jochens and Watson, 2013). The structure and synthetic nature of such a database calls for (1) a mechanism to create, populate, and maintain relevant data sources in a public format as assessment, restoration, and monitoring activities continue and (2) a longterm mechanism for additional input and maintenance with dedicated funding.

Thus although past, current, and future data collection and monitoring efforts will likely provide much of the needed baseline data from which the impact of future events such as the DWH oil spill on ecosystem function and structure could be discerned, the need for an overarching structure to integrate the wealth of data that has been, is being, and will continue to be collected in the GoM is viewed by this committee as a critical research need.

Finding 6.5. Several federal agencies, such as NOAA and the U.S. Navy, already maintain a number of background data repositories. There is, however, no integrative superstructure or roadmap to available data. The development of such a capacity will be even more essential as new data arrive from current and future research activities in the GoM. Needed is a database that can create, populate, and maintain relevant data sources in a public format as assessment, restoration, and monitoring activities continue. Creating such a database can only be successful if there is a long-term mechanism for additional input and maintenance with dedicated funding.

Over the past several decades, there have been several efforts to develop assessments and research and monitoring plans for the GoM. Much of the information derived from these efforts is relevant to better understanding of the GoM ecosystem, its components, and its processes, but is not entirely applicable to the needs of research concerning the fate and effect of the DWH oil spill. As stated throughout this report, however, a fundamental understanding of the GoM ecosystem is critical to application of an ecosystem services approach to damage assessment and restoration. Therefore, these research directions, while not explicit in their identification of ecosystem services, may enlighten the bigger picture.

The most recent process to develop a stakeholder-driven plan that identifies and addresses regional research priorities began with the Gulf of Mexico Alliance, with funding from the National Sea Grant Program, to assist GoM groups that conduct or use marine and coastal research. This regional plan is similar to seven others around the United States that also address the Ocean Research Priorities Plan (NSTC Joint Subcommittee on Ocean Science and Technology, 2007) resulting from the U.S. Ocean Commission and subsequent National Ocean Policy. Initial efforts to bring stakeholders together were set back by Hurricanes Katrina and

Rita in 2005, but eventually five workshops were held across the Gulf region to identify existing research plans and the needs of the Gulf constituency at all levels. The plan (see Box 6.1) was complete at the time of the DWH oil spill, and the four Gulf of Mexico Sea Grant Programs reexamined the plan immediately after the spill.23

In addition to the GoMRI initiatives, over the next 2 years, the GoM Regional Sea Grant Consortium, the EPA Gulf of Mexico Program, and NOAA are sponsoring $1.3 million in research aimed at improving approaches for valuing the GoM ecosystem services. In particular, the research will focus on the services provided by marshes, mangroves, and oyster reefs. The GCOOS-RA24 has a detailed plan for “A Sustained, Integrated Ocean Observing System for the Gulf of Mexico (GCOOS): Infrastructure for Decision-making” (the Build-Out Plan; see also Jochens and Watson, 2013). The GCOOS-RA has worked over the past decade to identify stakeholder needs for data, information, and products about the GoM, its resources, and its ecosystem. These results were used by the GCOOS-RA Board to identify the key elements of the GCOOS Build-Out Plan, the first version of which is complete. However, this plan will continue to develop and evolve, especially in view of the oil spill and developing restoration plans.

NOAA and collaborators have developed the Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Monitoring Implementation Plan for an Operational Observation System (2009, revised 2012). The Gulf of Mexico Alliance and the GCOOS-RA are developing the Harmful Algal Bloom Integrated Observing System. All of these monitoring plans were constructed with the input of multiple stakeholder groups, including representatives from academia, state and federal agencies, industry, recreational and commercial fishers, tourism interests, boaters, health service agencies, resource managers, and members of the public. Thus, the plans, and necessary implementation, serve to improve not only long-term and broad data collection and thus our understanding of the GoM, but also societal needs.

Multiple observatory systems will establish critical time series that can be used as baseline data should another event such as the DWH oil spill occur. The Ocean Research Priorities Plan (NSTC Joint Subcommittee on Ocean Science and Technology, 2013) emphasizes the critical need for ocean observations at scales that are temporally and spatially relevant for decisions concerning effective adaptation, management, and mitigation. At the same time, consideration should be given to maintaining vessel and satellite capabil ity. Both science and policy call for improving integrated ocean observing capability across the United States and internationally.

Updated Research Priorities Report

Six years have passed since the Ocean Research Priorities Plan (2007) was developed. An updated report (NSTC Joint Subcommittee on Ocean Science and Technology, 2013) says the DWH oil spill highlighted the “complex interplay of society and human health with chemical, physical, and biological aspects of the ocean and our coasts.” The report emphasizes the “wide

_________________

23 The revised version of the Gulf of Mexico Research Plan is available at http://masgc.org/gmrp.

BOX 6.1

The Gulf of Mexico Research Plan: An Opportunity to Improve

Our Understanding of Ecosystem Services

The range and scope of research needs for the Gulf of Mexico are extensive and require prioritization in order to be effective and responsible with the available funding. Fortunately, some 1,500 people from over 250 universities, government agencies, businesses, NGOs, and other organizations worked together to provide broad constituent input in the development of the Gulf of Mexico Research Plan (GMRP). The goal of the plan is to assist the GoM research community, including those who conduct or administer research or use research findings.

The highest-rated GoM research priorities were organized into five theme areas: (a) ecosystem health indicators; (b) freshwater input and hydrology; (c) habitats and living resources; (d) sea-level change, subsidence, and storm surge; and (e) water quality and nutrients. The committee found many of these priorities to be consistent with those we have identified for advancing our understanding of ecosystem services in the GoM and that would be useful for enhancing community and ecosystem resilience in preparation for future environmental challenges, whether they are episodic (i.e., oil spills or hurricanes) or chronic (i.e., sea level rise and wetland loss) events.

Of the many research priorities presented in the GMRP, only a few mention ecosystem services specifically, but most of them provide a starting point for research that would support a better understanding of ecosystem services in the GoM. Following are some key examples of how the scope of ongoing work might be enlarged toward this end. The relevant Ocean Research Priorities Plan (ORPP) priority number is identified for each focus area.

• Understand and predict the impact of natural and anthropogenic processes on ecosystems (ORPP Research Priority 14).

Understand how the current level of regional development and human-engineered infrastructure influences the flow of freshwater into the GoM and how much of that inflow and sediment discharge is needed to support healthy and functional wetlands in light of challenges such as sea level rise and habitat loss due to erosion.

There is also a suite of factors that relate to land use—pollution and storm water runoff, wastewater, and nutrient loads from agriculture—that contribute to a number of chronic problems in the GoM, such as harmful algal blooms and hypoxia zones. A key priority is to examine their impacts on ecosystem health, sea grasses, biodiversity, and higher trophic organisms.

• Develop socioeconomic assessments and models to evaluate the impact of multiple human uses on ecosystems (ORPP RP15).

Identify the social and economic drivers that influence how communities use, conserve, and protect their natural resources. It would be useful to identify and estimate the socioeconomic tradeoffs associated with changes in protecting and restoring resources and ecosystems at various scales.

• Develop appropriate indicators and metrics for sustainable use and effective management of GoM marine resources and ecosystems (ORPP RP16).

Identify appropriate tools and techniques that can evaluate the status and health of ecosystems and resources, specifically those that can be used readily and quickly in the field for the detection of harmful levels of bacteria, contaminants, toxins, and pathogenic organisms.

• Stewardship of Natural and Cultural Resources: Understand interspecies and habitat/species relationships to support forecasting resource stability and sustainability (ORPP RP2).

Identify and model the connections among and between habitats and living marine resources for the goal of supporting sound ecosystem-based resource management decisions. This would include tracking changes in habitat quality (and quantity) and in ecosystem structure and function in order to be able to identify the effects of these changes on marine organisms and their populations.

• Understand human use patterns that may influence resource stability and sustainability (ORPP RP3).

Establish the value of GoM ecosystem services, including depleted and renewable resources, to allow for informed decisions on the placement, construction, development, and expansion of large-scale commercial and industrial enterprises.

• Increase resilience to natural hazards by developing multihazard risk assessments and models, policies,and strategies for hazard mitigation (ORPP RP7).

Determine and predict the physical impacts of climate change on coastal and upland areas in terms of factors such as sea level change, rate of elevation change, shoreline change, loss of barrier islands, and change in regional hydrology and apply this knowledge in habitat restoration efforts. It will be important to examine the public’s perception of sea level change and find effective ways to communicate the issue at the individual, community, and government levels.

Predict socioeconomic impacts of climate and sea level change on population dynamics, community infrastructure, and on short- and long-term community demographic shifts.

Characterize and model community and ecological resilience to natural hazards, considering the ecological footprint and level of vulnerability of the built environment, and identify methods to reduce losses. Model the attributes, factors, and strategies that contribute to making a community successfully resilient.

• Understand response of coastal and marine systems to natural hazards and apply that understanding to assessments of future vulnerability to natural hazards (ORPP RP6).

Many of the same challenges for increasing resilience for human communities exist for the natural ecosystems of the GoM, so there is a need to determine how storm surge, subsidence, and sea level change affects ecosystems.

Identify the optimal use and allocation of sediment and evaluate the rates of shoreline change from anthropogenic and natural impacts, including sediment mobilization, transport, and deposition from major storm events.

Analyze how coastal and near-shore morphology and biota protect inland areas from hurricane impacts by absorbing wind and storm surge energy and determine the economic costs and benefits of this protection.

• Understand the impact of climate variability and changeon the biogeochemistry of the ocean and implications for its ecosystems (ORPP PR12).

Determine changes in freshwater, nutrient, pollution, groundwater, and sediment input due to changes in pattern and quantity of precipitation and predict the subsequent impact of these inputs on geochemical and physical coastal processes and biological communities.

and reverberating impacts that the loss of ocean and coastal resources can have on our country” as well as on local coastal communities, both ecological and sociological.

The report identifies “significant areas in need of improvement, including our ability to monitor and observe the ocean in real time; to rapidly share information; to understand, model, and predict the consequences of extreme events in the context of a changing ocean; and to apply those insights to a rapid and effective response.” It also identifies an important overarching soci etal theme—global change—that requires a more realistic and forward-thinking treatment of restoration responses. The 2013 update also illustrates the direct link between the research priorities and the application of basic research to sound policy and manage ment decisions. Fundamental research continues to be the anchor for issues that have the potential to alter our economy, our security, our environment, and our daily lives. In this vein, the research priorities related to the effects of major oil spills and the recovery of ecological and social systems still require more emphasis on ecosystem services and how they are defined, measured, and equated to ecosystem processes and functions.

There are numerous research plans for the GoM, well-planned scenarios for observation systems, and numerous documents on how restoration should proceed. More plans will be added as various agencies, councils, and states (as outlined in the RESTORE Act) develop guidance for measuring the effectiveness of restoration and monitoring efforts. These plans often do not clearly identify ecosystem services, but in attempting to capture the workings of the GoM ecosystem, they enhance the understanding of GoM ecosystem processes that is essential to the understanding of ecosystem services. The next section discusses how research efforts can be enhanced to specifically address ecosystem services.

Research Needs Specific to Ecosystem Services and Their Valuation

As discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, the fundamental challenges to application of an ecosystem services approach to damage assessment in the GoM are related to understanding of baseline levels in a shifting or dynamic regime, the lack of comprehensive mechanistic models of GoM ecosystem processes, the uncertainty of and limited data associated with characterizing the human benefits that flow from ecosystem services, and finally, relating ecosystem services to long-term resilience.

Given the substantial ongoing data collection efforts undertaken in response to the DWH oil spill, along with the planned research and monitoring efforts, the baseline data needed to determine the impact on ecosystem function and structure of a future event such as the DWH oil spill will likely be available. Although an important component of the ecosystem services approach, appropriate baseline data alone are not sufficient for full implementation of an ecosystem services approach to damage assessment, particularly in a regime as dynamic as the GoM. Critical to the success of an ecosystem services approach is a better understanding of the mechanistic linkages between processes in the ecosystem—the ecological production functions described in the Interim Report (NRC, 2011) and Chapter 2. Development of these

ecological production functions for the GoM will be challenging, but they are essential to any effort to implement a full ecosystem services approach.

End-to-End Ecosystem Models

Ideally, the best solution to being able to quantify ecosystem services in the GoM (and thus the impact of an event such as the DWH oil spill on those services) is to develop end-to-end models for assessing the interplay of chemical, physical, biological, and socioeconomic conditions in the GoM. Such models would provide mechanisms to more fully understand the potential impacts of the spill on GoM ecosystem services. End-to-end models are complete system models that can relate drivers of change, such as climate change, to effects on ecosystem structure and function, such as the biomass of a particular subcomponent of the ocean biota (Fulton, 2010; Rose et al., 2010; Travers et al., 2007). In traditional compartmentalized thinking, these two ends may be viewed as being unconnected or there is a failure to investigate links that effectively connect them. Although a single end-to-end model that incorporates all of the relevant processes—biophysical and socioeconomic dimensions—and describes the dynamics of the provision of all GoM ecosystem services would be ideal, it is probably unrealistic to expect such a model to be developed for a system as complex at the GoM.

Currently, no single ecosystem model incorporates the full range of physical, chemical, or biological processes, let alone one that also fully incorporates an ecosystem services approach that further integrates socioeconomic dimensions. The models presented in Chapter 2 (Ecopath with Ecosim, Atlantis, Marine InVEST, MIMES, ARIES), however, allow for evaluation of the impact of an event such as the DWH oil spill on components of the ecosystem and the extrapolation of those impacts to a subset of ecosystem services. The Marine InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Environmental Services and Tradeoffs)25 models provide the ability to explore some of these dependencies, trace the spill’s impact on the capacity of systems to provide ecosystem services, and valuate the changes in ecosystem services to various groups in society. InVEST models are based on production functions that define how an ecosystem’s structure and function affect the flows and values of ecosystem services. With validation, these models can also provide useful estimates of the magnitude and value of services provided. Marine InVEST could also be used to analyze tradeoffs among bundles of services provided under different management alternatives—for example, differences in rebuilding a barrier island for wave surge protection versus one for tourism.

Ecosystem models, such as Atlantis, could be modified to support an ecosystem services approach because they include both shallow- and deep-water components of the ecosystem, chemical and physical processes, and certain components of human dimensions.

Finding 6.6. Future efforts should be focused on expanding the current generation of ecosystem models, or coupling them with other models, so that they may better approach the “ideal”

_________________

goal of an end-to-end model. Inclusion of the human dimension and economics into these types of models is essential to their capability to value changes in ecosystem services following disturbances such as oil spills. As these models are further developed and verified, they will help to improve our understanding of the full value of ecosystem services provided by the GoM ecosystem, as well as inform national efforts to prepare management plans to improve and protect the services for future generations. The development of a single end-to-end ecosystem/ socioeconomic system model for the GoM may never be fully realized; however, the development of submodels of key components of the system is a critical research area that needs to be addressed.

Submodels

In the absence of completed and validated end-to-end models, submodels of components of the GoM ecosystem can be used to establish the value of ecosystem services within a distinct resource use, location, habitat, and user community. Because they only model part of the system, submodels may miss important connections with the unmodeled portions of the system. If constructed in a compatible manner, however, these submodels could be joined to build a more complete representation of GoM ecosystem interactions.

Fishery ecosystem models (FEMs) are an example of carefully detailed submodels that consider the biological components of the system as well as the socioeconomic aspects of the fishery. The FEM structure reflects the priorities of fishery managers and harvest activities. Thus the model includes the monitoring and management processes related to fisheries. The state of biological stocks can be integrated with the value of economic benefits derived from the fishery. FEMs allow researchers to narrow the set of possible hypotheses to be tested when an ecosystem is disturbed by environmental change or human activities. These models can help in the design of studies to collect the necessary data to more closely estimate the effects of an environmental impact on future fishery and ecosystem productivity. One type of FEM, Ecopath with Ecosim (EwE), is a modeling framework that integrates a wide range of biological and fisheries dynamics for multiple species and functional groups (biomass pools) over long time periods, using a trophic mass-balance approach (Christensen and Walters, 2004). Although originally designed as a FEM, EwE is used to address many aspects of marine ecosystem dynamics, including analyses of impacts from the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in the Prince William Sound ecosystem (Okey and Pauly, 1999). EwE could be used to identify the components of the model ecosystem most likely to be affected by the DWH oil spill.

Merging Social Benefits to Ecosystem Models

This report has described the plethora of past and current data collection activities. The vast majority of data collection activities are directed to generating sufficient baseline data about ecosystem function and structure or effects of particular response technologies. Effective implementation of an ecosystem services approach also requires collection of socioeco-

nomic data. “Making the public whole” after a disturbance such as the DWH oil spill requires an improved understanding of its impacts on the value of various ecosystem services and on the populations and communities most affected. In many of the research programs mentioned above, with the exception of the GoM Sea Grant Consortium, the impacts on human communities are not rigorously integrated with ecosystem research. Although a stated goal of many of the programs is that their results will benefit society, a formal linkage between their biophysical output and the impact on human well-being is missing.

The public is not homogeneous. Individuals and communities are affected by disturbances that alter the flow of ecosystem services in different ways. In addition, they differ in their preferences for what services are important and what services should be restored (or compensated for in some way). For example, an individual with a seafood packing and distribution company in Houma, Louisiana, and a subsistence fisher living in a subsiding marsh landscape south of Houma in Terrebonne Bay will have different perceptions of how the loss of a seafood supply affects their livelihoods.

Submodels of a fishery, management decisions, and economics of a particular product could be developed that include the different types of social structures that depend on the fishery resources. Some values derived from fisheries, such as the profits of a commercial fishery, are much easier to estimate than others, such as the value of subsistence fishing. A comprehensive analysis should strive to understand important benefits, even those that are difficult to assess. The data needed to assign a value to the loss of the provisioning services of fisheries (see Table 5.6) would include length of period that the fishery was closed, estimated loss of catch, value of catch, alternative revenue streams, public perception of seafood safety and economic losses from buyer concern, unemployment costs, and loss of licenses that would link the fishery catch reduction and economic hardship to the various groups in society that depend on that fishery.

Tracking these variables offers a rather straightforward approach to monitoring the recovery of a community from an event such as the DWH oil spill if the goal is simply to return the community to its pre-spill state (the concept of engineering resilience discussed in Chapter 3). If, however, the event causes the system to undergo a regime change, then it will be much more difficult to determine the nature of the recovery (the concept of ecological resilience discussed in Chapter 3). Future research efforts should collect data on the benefits derived from ecosystem services by various groups and communities so that appropriate models can be built that include the full range of socioeconomic impacts including, as discussed below, those that may involve regime changes.

Finding 6.7. A necessary step in modifying submodels that characterize specific components of the GoM ecosystem—such as the fishery ecosystem models (FEMs)—is to integrate a socioeconomic evaluation of a spill impact such as a reduction in fishery productivity and the subsequent economic loss to coastal communities. FEMs should be extended to include additional data that would allow estimation of ecosystem service values for the affected fishery. Other subcomponents of the GoM ecosystem and the services they provide (e.g., wetlands, deep sea,

etc.) need to be modeled, which is a more realizable goal in the short term than constructing an end-to-end model.

Merging the Concept of Resilience to Ecosystem Service Models

As discussed in Chapter 3, the concept of resilience, the capacity of a system to respond to disturbances, is a potentially important component of ecosystem management to provide for a continuing flow of valuable ecosystem services. That chapter also discussed the importance of viewing resilience from an integrated social-ecological perspective that incorporates the links among human actions, ecosystem structure and function, and human well-being. Achieving social-ecological system resilience is, in reality, quite difficult and requires considerable additional research into the determinants of resilience both in principle and in its application in particular systems.

Finding 6.8. There is a lack of integrated systems research capable of analyzing the links between socioeconomic systems and ecosystems, as well as a lack of understanding of the complex feedbacks between components of systems necessary for understanding overall system dynamics and resilience. It may be possible to find key indicators that signal when systems are approaching thresholds. Improved methods to detect and avoid crossing thresholds that lead to reductions in valued ecosystem services could provide decision makers with the information they need to better manage the GoM system.

Whether or not management of social-ecological system resilience is consistent with current resource management laws is not fully clear. If management for resilience represents a significant change from current management and decision-making processes, then congressional authorization in the form of new or amended laws would be required to make it part of the process (see e.g., Ruhl, 2012). To fully implement a resilience approach into practice, an agency would need to (a) craft a firm definition of resilience for the system in question, (b) identify a means of measuring the current state of that system’s resilience, (c) build a model capable of predicting to some degree of certainty the resilience effects of specific decisions (or to design management experiments that could lead to the development of predictive capacity), and (d) develop these tools such that it can explain both the process and the results to the public and to the judges likely to review its decisions (Allen et al., 2011). The current state of knowledge and practice falls far short of these standards.

Valuing Ecosystem Services

Ascribing value to ecosystem services is typically done using economic valuation methods. These methods are capable of generating estimates of the value of services in terms of a common (monetary) metric. One of the challenges to applying an ecosystem services approach

to the DWH oil spill, particularly with respect to whether it can supplement the existing NRDA process, is that for many ecosystem services, there is either a lack of values associated with functions, a lack of data, or both, preventing accurate quantification of ecosystem services as a function of ecosystem condition. Approaches and tools for assigning values to the ecosystem services impaired by the DWH oil spill will need to be developed and applied appropriately, particularly for ecosystem services for which data on human preference and use are lacking. Some services are more readily quantified than others. For example, several studies have estimated the value of coastal marshes in providing hazard mitigation during hurricane wave surges on coastlines (see Chapter 5). The valuation may consider changes in costs and availability of home insurance coverage or estimates of the likely reduction in damages with intact marsh versus without intact marsh. The monetary values of provisioning services, such as commercial and recreational fishing, or regulating services, such as nutrient and pollution removal, can also be fairly easily estimated. More challenging is the assignment of economic value to other, less tangible impacts on services, such as changes in community vitality, way of life, or aesthetics or spirituality, or biological interactions in the mesopelagic portion of the northern GoM. Although these valuation issues are challenging, they must be addressed to enable comprehensive and consistent measurements of losses or changes of ecosystems resulting from environmental harm.

Finding 6.9. Consideration of the impact on human well-being of the DWH oil spill is of great importance, but the ability to analyze these impacts is still partial and incomplete. Consistent frameworks exist for inclusion of these impacts on human well-being (e.g., NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science “Human Dimensions Strategic Plan” or the Marine InVEST models), yet our ability to integrate socioeconomic analysis with biophysical analysis lags behind. Models in which the stakeholders are identified, the impacts they experience are described, and the methods for assigning values to the loss or change in ecosystem services they experience should be explored.

SUMMARY

As discussed throughout this report and the Interim Report (NRC, 2011), the committee believes that an ecosystem services approach to damage assessment offers several advantages over current practice. However, the research, data, and models needed to more fully implement this approach are lacking.

The research funding and the release of NRDA data that will be available through the settlement process offer an unprecedented opportunity to establish a comprehensive baseline measurement and and greater fundamental understanding of the GoM, both which are critical components of an ecosystem services approach. The committee has identified several key areas of research that are needed to fully implement an ecosystem services approach for the GoM.

1. Although past, current, and future data collection and monitoring efforts, with appropriate modifications, could likely provide much of the baseline data needed to discern the impact of events such as the DWH oil spill on ecosystem function and structure, an overarching structure, supported by long-term and stable funding mechanisms, to integrate all of these efforts in the GoM is critically needed.

2. The development of a single end-to-end biophysical-social-economic system model for the GoM would be ideal, but is probably not likely for a system as complex as the GoM. Instead, the short-term focus should be on the development of submodels of key components of the GoM ecosystem and the services it provides (e.g., fisheries, wetlands, deep sea, etc.). These submodels must consider the impacts on human well-being and include approaches for valuing the ecosystem services. Ultimately, these submodels could be combined in work to establish a more complete ecosystem model for the GoM.

3. The committee believes that plans for current and future data collection may provide sufficient baseline data about ecosystem function and structure. The ecosystem services approach, however, is limited by a lack of socioeconomic data, which are needed to better inform understanding of the human dependencies on natural systems and therefore the socioeconomic impacts of disturbances such as the DWH oil spill. Future research efforts must include the collection and synthesis of data on relevant human factors to enable development of models that consider the full range of socioeconomic impacts.

4. Understanding of resilience in a socioecological context is critical to this approach, but it requires considerable additional research into the determinants of resilience, both in principle and in application, in particular systems. Proper integration of resilience theory into management decisions—for example, criteria for success in restoration— will require resolution of current legislative barriers.

5. With respect to response technologies, the need to accurately predict the effectiveness of injection of dispersant at depth, the impact of dispersants on biodegradation rates, and the long-term effects of dispersed oil on the food web and other ecosystem services is most critical.

The risk of additional deep-sea reservoir oil spills in the GoM increases as the oil and gas industry moves more and more into deeper waters. Consequently, stakeholders should consider how the nation should prepare for an environmental event of the magnitude of the DWH oil spill. For instance, what is the unifying framework for addressing research, monitoring and modeling needs for baseline conditions, mitigation approaches, valuation of environmental impacts and loss of ecosystem services, and restoration of natural and social systems? How would success or effectiveness of these efforts be estimated?

Statements were made after the Exxon Valdez grounding and oil spill that lessons learned from that spill would serve the nation in its response to the next large oil spill (Kurtz, 1995; Peterson et al., 2003). Legislation, such as the 1990 Oil Pollution Act, was passed to better ensure cleanup and responsibility for damages to the ecosystem. Although some people familiar with

the complexity of the deep ocean may have anticipated the failure to contain a spill there, the nation as a whole was not prepared for the magnitude of new and critical issues presented by the explosion and sinking of the Deepwater Horizon and wellhead rupture of the Macondo well. There are countless opportunities, at present, to ensure that the nation is better prepared for a similar incident in the future. These opportunities should not be wasted.

The NRDA guidelines continue to be used to assess damages from the DWH oil spill. Just as better mechanisms for assessing and assigning responsibility for damages resulted from the Exxon Valdez grounding, the opportunity exists now to incorporate the concepts of ecosystem services, in practice and in law, into oil spill damage assessment and recovery strategies. The evolving understanding of human-ecosystem interactions as articulated by ecosystem-based management, and particularly the concept of ecosystem services, offer an opportunity to address some of the challenges faced during the current NRDA process. By taking a more holistic view of ecosystem interactions, and by following these interactions through all relevant trophic levels and spatial connections to their ultimate impact on human well-being, an ecosystem services approach to damage assessment can capture a more complete picture of potential impacts of a damaging event and offer a broader range of restoration options. By coupling the concept of ecosystem resilience with socioeconomic resilience, we would further ensure that an ecosystem services approach would come closer to restoring social-ecological systems after damage from a human-caused or natural disturbance.

In closing, GoM communities and natural resource managers face many challenges as they contemplate and set research priorities and select restoration plans. It will be important for all stakeholders to think about “how best to manage multiple ecosystem services across a diverse natural and sociological marine ecosystem?” As many in the region have already realized, past decisions to enhance a particular ecosystem service to maximize a particular benefit—for example, energy development, fisheries, tourism—may have resulted in tradeoffs that diminished the ecosystem’s capacity to provide other services. The ecosystem services approach could be used to more fully capture the value of assorted services in the GoM, which would assist GoM communities in identifying what is important to their way of life and would inform management decisions regarding the balance among ecosystem service priorities.

This page intentionally left blank.